Abstract

Over the last two decades, digital photography has been adopted by young and old. Many young adults easily take photos, share them across multiple social networks using smartphones, and create digital identities for themselves consciously and unconsciously. Is the same true for older adults? As part of a larger mixed-methods study of online life in the UK, we considered digital photographic practices at two life transitions: leaving secondary school and retiring from work. In this paper, we report on a complex picture of different kinds of interactions with visual media online, and variation across age groups in the construction of digital identities. In doing so, we argue for a blurring of the distinctions between Chalfen’s ‘Kodak Culture’ and Miller and Edwards’ ‘Snaprs’. The camera lens often faces inwards for young adults: tagged ‘Selfies’ and images co-constructed with social network members commonly contribute to their digital identities. In contrast, retirees turn the camera’s lens outwards towards the world, not inwards to themselves. In concluding, we pay special attention to the digital social norms of co-creation of self and balancing convenience and privacy for people of varying ages, and what our findings mean for the future of photo-sharing as a form of self-expression, as today’s young adults grow old and retire.

INTRODUCTION

People engage in the photographic practices of taking and sharing photographs (photos) for a number of reasons: communicative purposes (Miller and Keith Edwards Citation2007; Stefanone and Lackaff Citation2009), to help shape their social identity (Harrison Citation2002; Siibak Citation2009), and not least, to capture and augment memories (Van Dijck Citation2008; Kuhn Citation2007).

The questions of how and why individuals capture photographic images have been considered across disciplines. An anthropological lens has been applied by Chalfen (Citation1987) and Sontag (Citation1977) to examine how and why individuals capture images. Chalfen coined the term ‘Kodak Culture’ to describe people who take photos of events like holidays and celebrations and share those photos with key people linked to the photo subjects. Miller and Edwards (Citation2007) identified a second group of photographers, ‘Snaprs’, whose photos largely remain in digital form, represent everyday events rather than special occasions (Twenty Pixels Citation2013), and who share images more widely than participants in Kodak Culture. Although Miller and Edwards do not use age as a distinguishing factor for Kodak Culture vs. Snaprs (both of their groups were in their 20s and 30s), later work links Kodak Culture with older adults (e.g., Hope, Schwaba, and Piper Citation2014).

If people are taking photos to communicate, to shape their social identity, and to capture and augment memories, are there particular times in their lives when they might be more likely to take and share photos? Previous work in Human Computer Interaction (HCI) has examined the value and importance of photos with people within age classes, including young (Van Dijck Citation2008; Durrant et al. Citation2009; Durrant et al. Citation2011) and older adults (Apted, Kay, and Quigley Citation2006; Lindley, Harper, and Sellen Citation2009; Waycott et al. Citation2013), but none of these studies explicitly explores variation and complexity in photo taking and sharing across age classes.

Our contention is that life transitions may affect photo taking and sharing behaviours. By life transition, we mean a period in time when individuals experience major life changes, either intended or unintended. Intended transitions may include moving from school to further education, becoming a parent, or retiring. Unintended transitions may include (e.g.) becoming a carer, or experiencing the break down of a relationship (George Citation1993). Life transitions are often characterised by a period of instability, as the central actor typically makes major adjustments to life circumstances, coping with new experiences and developing new skills (Hulme Citation2014). Some HCI work has looked at digital technology use around particular life events, such as getting married (Massimi, Harper, and Sellen Citation2014), relationship break down (Moncur, Gibson, and Herron Citation2016) or the loss of a job (Burke and Kraut Citation2013). The literature on technology use across life transitions, however, with a focus on how such transitions change what photos are captured and shared, remains underexplored.

In this paper, we consider photo taking and sharing, using data gathered as part of a qualitative, ethnographic study of online life, augmented by quantitative data mining of the social network site Facebook.Footnote1 The insights into digital photographic practices emerged out of the data, as an integral part of contemporary online life. Study participants represented two different life transitions in the UK: (i) leaving secondary school (referred to in this paper as young adults); and (ii) retiring from work (referred to as retirees). We chose to study these two groups for two main reasons. First, how the self is represented photographically may change across the transition of either leaving secondary school or retiring. Second, these two groups may provide disparate perspectives on a topic relevant across the human lifespan – the future of photo capture and sharing – because of their differing ages and life experience with technology.

By thinking about how our participants were ‘doing’ photography in the context of a transition, we were able to develop insights into the context of our participants’ lives, not just their photo-taking behaviour in isolation. This approach allowed us to understand how taking and sharing photos currently varies across the lifespan, and how this social function of photography may change as today’s young adults become retirees in the future.

BACKGROUND

Photographic Practices as Components of Digital Identity and Personhood

Taking and sharing photos is a way for an individual to express versions of their experiences (Radley Citation2010), and to capture and invoke memories (Kuhn Citation2007). Photos may be widely shared with friends and to the world (Van Dijck Citation2011). As contemporary sharing of photos increasingly involves use of the Internet, photography contributes to online ‘knowledge production, interventions, and social action’ (Luttrell and Chalfen Citation2010, 197). It also serves as a medium for self-expression and identity in digital contexts (boyd and Ellison Citation2007; Graham et al. Citation2011; Mendelson and Papacharissi Citation2010; Sarvas and Frohlich Citation2011).

The role of photography in self-expression and identity can be understood through Goffman’s concept of the performance of self, whereby individuals craft and ‘perform’ edited representations of their social identities, and adapt them to fit different audiences (Goffman Citation1959). Photographs can serve as powerful visual elements in these performances of self. Their role has arguably been amplified as ‘the medium of dissemination’ (Luhmann, cited by Lee, Goede, and Shryock Citation2010, 142) has shifted from print to pixel, and the cost (both financial and time based) in copying and sharing photos has dropped significantly. This shift means that photos can now be shared online with large audiences with ease and minimal cost beyond that associated with being the owner of a smartphone.

Alongside the amplification of the role of photography in self-expression and identity comes a unification of photography with other media. Lee et al. note that ‘the digital medium unifies the differences between text, music, photographs and other media; interrupting their ability to restore form to communication on their own terms’ (Citation2010, 141). Photos no longer standalone: they have associated metadata, tags, and associations with other media in their presentation online, which enrich and contextualise their meaning (Botticello, Fisher, and Woodward Citation2016; Rose Citation2016; Pauwels Citation2015)

Thus digital photos contribute to the milieu of an individual’s digital identity. This term describes ‘how the data or information referring to people is created, captured, managed, verified and (ab)used by themselves and/or others (individuals, businesses or government) in life and death’ (Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Citation2015). A digital identity may include traditional identity information – physical characteristics like biometrics, name, and address (Emanuel and Stanton Fraser Citation2014) – as well as digital attributes like email address (Foresight Future Identities Citation2013), and online traces – the things that we post or that others post for us (such as photos, status updates, reports published online, or videotaped performances). Lee et al integrate the concept of digital identity in their discussion of digital personhood, which they define as having five elements: (1) a profile created on an online social network service, (2) expansion of one’s social media profile to allow for friend-seeking through shared likes/dislikes, (3) a digital ‘address’ (4) participation in digital friendshipsFootnote2 and (5) validation of the digital personhood of others. In short, digital personhood requires not only identity information to be present online, but also some interaction with others around that information. This leads us to the concept of networked individualism (Rainie and Wellman Citation2012).

The enactment of an individual’s multifaceted digital identity and digital personhood is performed through a networked individualism that enables individuals to ‘support, supplement and enhance face-to-face interaction’ (Rainie and Wellman Citation2012, 166). An important element of this networked individualism lies in networked content production, enabling individuals to perform their identities to wide audiences (ibid). In turn, members of these audiences can choose what content they want to consume, and also what content they want to edit and share with their own audiences.

Photographic Practices across Age Groups and Life Transitions

The enactment of digital personhood is increasingly performed by both young and old (Smith Citation2014; Madden et al. Citation2013). However, beyond broad theoretical distinctions (for example, between Kodak Culture and Snaprs described above), the literature reporting on the behaviour of young adults and older adults around photographic practices often points in different directions. Research on young adults’ practices tends to focus on use of photos for self-presentation (Mendelson and Papacharissi Citation2010; Mazur and Kozarian Citation2010), and in particular, problematic photo sharing such as sexting (Chalfen Citation2009; Weiss and Samenow Citation2010). Research on older adults’ photographic practices is more diverse. Baecker and colleagues, among others, have focused their work on older adults using visual digital media to reflect on past experiences, e.g., (Citation2012), whilst Waycott and colleagues (Citation2013) focused specifically on older adult content production through a prototype iPad application (app).

Although extant literature suggests that individuals may capture and share more photos at life transitions, a comprehensive study to support this contention has not been undertaken, likely because it would require following large numbers of participants for an uncertain amount of time as they moved through their lives. The duration of a life transition might vary across participants: while the actual transition event (leaving secondary school) could be accomplished in a single day, the changes associated with moving from a secondary student role into further education, training, or employment, could span several months or more, with photographic practices changing incrementally over this period. The sociology literature suggests that studies of individuals’ experiences of transitions tend to focus on the impact of historical events (e.g., the Great Depression or World War Two) or early life events (e.g., childhood trauma or entering the first year of school) on subsequent life patterns (George Citation1993). Our study reported herein differs from these studies by focusing on a particular set of behaviours (photo taking and sharing) at two life transitions, and asking what we can learn about present variations – and infer about future ones – in these behaviours, based on how our different-age participants behave.

Current Norms and Reflections on the Future of Photographic Practices

In addition to examining photographic practices through the lens of digital personhood, we ask why young adults and retirees share photos as they do, and what conclusions might be drawn about the future of photo-sharing based on emerging digital social norms. Social norms refer to ‘prescriptions of behaviours and attitudes that are considered acceptable or not in a given social unit’ (Chekroun Citation2008, 2142). We define digital social norms as socially normative behaviour in a digital age, discerned from social expectations of online behaviour that are often not articulated, and how individuals respond to these expectations. Researchers characterising social media have expressed these types of norms (e.g., Fleming, Vandermause, and Shaw Citation2014; Tufekci Citation2008; Moncur, Orzech, and Neville Citation2016) but not with a specific focus on photos, across life stages, nor with a focus on what current online behaviour may mean for the future.

The design of our larger study, Charting the Digital Lifespan (CDL), allows us to explore variation among younger and older users in the context of photo taking and sharing. Although our approach is necessarily cross-sectional, capturing a transitional period in each participant’s life rather than following participants longitudinally across the lifespan, reflecting on photographic practices across life transitions permits us to see both groups celebrating rites of passage, reconfiguring their balance between school/work and leisure activities, and making changes to their online presence. With data on these changes, we begin to build evidence for complexity and variation in the presentation of digital self across age groups, to question the future of photo taking and sharing based on what we know about current practices, and also to address the dichotomy between Kodak Culture and Snaprs first raised by Miller and Edwards (Citation2007) that remains pertinent today.

APPROACH

Methods

Method 1: Our methodological approach involved conducting a qualitative ethnographic study of participants’ online lives. Ethnography is defined as ‘a scientific approach to discovering and investigating social and cultural patterns and meaning in communities, institutions and other social settings.’ (Schensul, Schensul, and LeCompte. Citation1999, 1) and can be accomplished through a variety of qualitative and quantitative methods. presents details on our qualitative methods of semi-structured interviews and participant observation, along with a brief description of the data derived from each method.

TABLE 1. Qualitative ethnographic methods used.

The research participants were (i) 15 young adults who had recently left secondary school, and (ii) 15 retirees, who had recently retired from work. Interviews and observations all took place in the same mid-sized city (~150,000 residents) in the UK between December 2013 and March 2014. Our participants were recruited through community contacts. They were ordinary individuals, not early technology adopters, recruited so that we could study their personal practices around taking and sharing photos. presents brief demographic information about study participants, included to show that we sought diversity of sex, age, and occupation among participants in our qualitative ethnographic study.

TABLE 2. Participant demographics.

During the semi-structured interviews, participants were asked four specific questions about their photo taking and sharing behaviour:

What types of photos are taken?

How are photos shared?

Why are photos shared?

What is the future of photos in online life?

We asked participants to think broadly about their photo taking and sharing behaviour, not just taking photos on their mobile phone and sharing via Facebook. In particular, we encouraged reflection upon the types of subject matter represented within the photo content that participants shared, whilst minimising our influence regarding what those content classes (topics) should be. We asked participants to describe the types of photos that they took, rather than (for example) ask them to sort a set of photos to derive classes. By interviewing participants shortly after they experienced a life transition, we captured their perceptions and behaviour around what changed in their ‘digital lives’ as they made the transition. With technology such as Facebook and mobile phone cameras at their disposal, our participants could easily show us what they were taking pictures of ‘now’, i.e. at the current time, and in some cases take us ‘back’ to the time of the transition to show us what they were taking pictures of ‘then’ as well. Whilst our method did not involve a formal photo elicitation technique (Pink Citation2013), we did use the photos that were shown and available ‘to-hand’ to stimulate sense making at interview between the researcher and participant, and to help develop the researcher’s ethnographic insight.

Method 2: The above method was complemented by data from a quantitative study conducted as part of the larger (CDL) project. In this study, the classification of approximately 5,000 photographs from Facebook was undertaken via an application developed by our collaborators at another UK university (James and Collomosse Citation2016). Participants in this part of the project were 22 first-year University students who each agreed to donate their Facebook photos to the project and spend 20 min classifying a small subset of the photos donated by both themselves and the other participants in the study. This activity was designed to provide baseline knowledge to inform the development of an automated classification algorithm (computer programme). The objective of the algorithm was to extrapolate from this human knowledge through machine learning, to classify the entire set of donated social media photos, enabling automated coding of those photos by topic. Participants in the classification exercise were asked to assign one or more of the following nine classes to each photograph they viewed:

Art

Attitudes & Beliefs

Family & Pets

Food

Friends & Peer Relationships

Holiday & Travel

Parties & Celebrations

Personal Style and Self Image

Sports

The specifics of the machine learning software are beyond the scope of this paper, but see James and Collomosse Citation2016; Collomosse et al. Citation2014 for details. Please see in the Findings section for a visual representation of how the categories of Method 2 were related to the category descriptions provided by interviewees in Method 1.

TABLE 3. Young adult and retiree descriptions of photos taken.

Data Analysis

Analysis of Method 1 data focused on ‘photo-talk’ in the research context (Frohlich et al. Citation2002; Durrant et al. Citation2009). Interviews and field notes were analysed using a Grounded Theory (GT) approach (Charmaz Citation2011; Strauss and Corbin Citation1990), which involves letting theory develop out of the data collected. This is achieved by first identifying initial themes through the line-by-line process of open coding, and then refining these themes into focused codes applied to additional transcripts. This approach allowed us to identify individual perceptions of everyday life experiences without preconceptions. For this paper, the focused codes ‘photo/video’, ‘online self’, ‘online community’, ‘content groups’, ‘browsing’ and ‘future of technology’ were considered in developing theory about photo taking and sharing.

Within this process, the content of photos was analysed in terms of the interviewee’s description of the photo at interview and in the context of applying GT, not through conducting a separate content analysis (Pink Citation2013). As each interviewee responded to the first question (What types of photos are taken?), the first author classified each photo as it was discussed during the interview; for example, if a participant’s description was ‘that’s a party photo’ then the photo was classified as a ‘party’ class of photo. As the ‘classes’ of photos developed during the GT analysis, the ‘party’ photo was re-classified under ‘Celebrations’. At the point in the project when the Method 2 exercise was held, nine classes (mentioned above), determined through researcher knowledge of photo classes commonly posted on Facebook, combined with pilot interviews with young adults had already been generated. So participants taking part in the Method 2 exercise manually selected one or more of the existing classes to apply to each photo that they saw. One of the challenges and rewards of this analysis was that research collaborators from very different disciplines – anthropology, human-computer interaction, and computer vision – were all working together to seek a cohesive explanation of how individuals classified photos.

FINDINGS

This section explores the answers to the questions above, given by our two groups of participants in Method 1: What types of photos are taken? How are photos shared? Why are photos shared? What is the future of photos in online life?

Throughout this section, individuals who are quoted are identified by a name, changed as part of the anonymisation process, followed by their actual age – e.g. Moira63. Further, in the photos shown in this paper (obtained from participants via Method 1 and 2), we have blurred faces to reduce readers’ ability to identify the people shown. This is consistent with ethical permissions provided by participants, and with ethical approval for this project granted by the University of Dundee.

Types of Photos Taken

Participants, across age groups in Method 1, identified 17 classes of photos that they took, which are listed in . This table also includes the nine classes developed by the researchers, so readers can see how the classes presented by project staff and research participants have aligned. Both young adults and retirees mentioned eight of the nine researcher-developed classes. ‘Attitudes and beliefs’ was one class that we included in the classification scheme that ended up not being used at all by research participants. As researchers, we understood that many Facebook posts, including posted pictures, could be described as expressions of this category. But while adults of all ages might re-share content on Facebook related to attitudes and beliefs, this was not a class they identified in their own picture taking and sharing behaviour.

In Method 2, 850 photos were classified based on their content. shows how many photos were assigned to each category by the 22 participants, with ‘friends and peer relationships’ the most used category.

FIGURE 1. How photos were categorised by 22 young adult participants (n = 850 photos). Participants could choose more than one photo category to describe a photo.

We found that 14 photo classes were common to both younger and older adults, although photos in these classes were taken at different frequencies within our sample. For a category such as ‘personal style and self image’, our participants applied several descriptors to those photos, such as ‘[me] working or volunteering’, ‘baby or embarrassing photos [of me]’ and ‘Me with…’ or ‘Me at…’ photos. Four classes mentioned by participants were not captured in our nine-category classification scheme – these include one type of photo unique to each age group, ‘something has happened’ (young adults), and ‘health issues’ (retirees), and two photo types common across both age classes – ‘items received or documented’, and ‘funny things’.

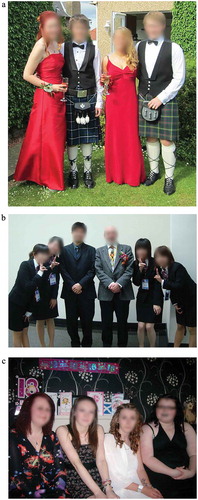

and b show examples of photos classified as ‘personal style and self image’ in which our participants appear. shows an example of a young adult’s photo that marks leaving school and the associated celebratory dance or prom. was posted by an older adult participant and shows him in a work conference situation. Other photos captured by both young adults and retirees include photos of family, holidays and travel, and parties and celebrations. shows a photo typical of the parties/celebrations category for young adults – an 18th birthday.

FIGURE 2. (a) Personal style and self image: Leaving School (Participant Kirsty18); (b) Personal style and self image: Work (Participant John69); (c) Parties & Celebrations (categorisation exercise).

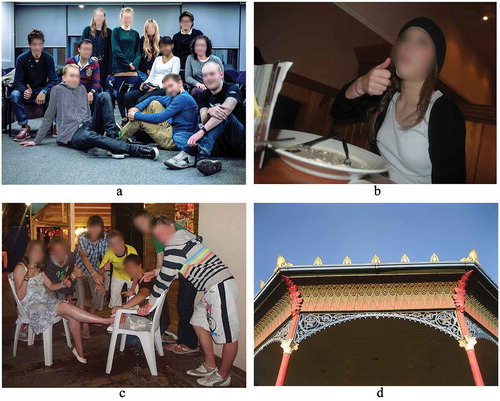

and b show young adults’ photos that were classified as ‘friends’ and ‘food’. depicts a group of friends. shows how the classes ‘food’ and ‘friends’ may overlap. One type of photo was unique to young adults: the ‘Something has happened’ photo. This photo was designed to visually represent one’s current ‘status’ and was posted to social media very soon after an event happened. shows a Facebook status update photo described by participant Rebecca21:

That’s an example of something I would put as a Facebook status, where I cut my foot open on a broken bottle at a Bastille Day party in France, and it was properly bleeding. Then all these guys who I’d met through the club [said], ‘Oh my God, she’s bleeding,’ carried me up to a bar area and they tried to do first aid, while my brother frantically ran about trying to find my parents. So that was good fun.

FIGURE 3. (a) Friends (categorisation exercise); (b) Food (categorisation exercise); (c) Something has Happened (Participant Rebecca21); (d) Buildings & History (Participant Moira63).

Two types of photos were unique to older adults – photos of architecture and historical sites (see ), and photos related to health issues. Some classes differed in their emphasis across groups – for example, while photos of animals were classed ‘zoo photos’ by a young adult, older adults focused more on birds and other wildlife in natural settings. Similarly, while young adults described a photo category as showing items that they purchased or received as a gift (a camera, a unique pair of shoes, truck tires) older adults documented things like structural repairs and house contents for insurance.

How Photos Are Shared

For almost all of our young adults, Facebook was their location of choice for sharing photos. The one exception did not have a smartphone and made minimal use of Facebook, although he still maintained an account he occasionally accessed on the computer. There was a focus on giving almost-immediate status updates online. Instagram, TwitterFootnote3 and the ephemeral-photo app SnapchatFootnote4 were also popular with our young adults. Some also occasionally shared photos via Reddit.Footnote5 One young adult used WhatsAppFootnote6 for sending photos to others because it was free. Two young adults referred to occasional photo-printing by themselves or friends, for example: ‘My friend actually has this [embarrassing photo of me] printed out and stuck on his wall’ (Lewis19).

Our retirees exhibited a range of photo sharing practices that were distinct from those of the young adults. Five retirees did not share digital photos online at all: however, three of them did occasionally print out photos, or showed them to others on their phone or computer. This offline sharing was sometimes used to document a period of time: for example, one retiree held a ‘winter slideshow’ for the youth group that he worked with as a volunteer. Amongst retirees that did share digital photos online, the most popular approach was to attach photos to an email. Only one participant posted photos on Twitter: these were mostly of her walking group in scenic locations, and of knitting problems. Three retirees had used or hoped to use FlickrFootnote7 to organise and share photos, while two reported attaching or receiving photos via text messages or the messenger WhatsApp. Although two-thirds of retirees had Facebook accounts, only one was a regular Facebook user and poster of photos, and five others reported that they currently or had previously shared photos on Facebook. Finally, two retirees emphatically did not want to share photos on Facebook, due to privacy concerns:

I don’t fully understand because …if I post something, I don’t have the full confidence that I’m saying something private that remains private and I don’t want my photograph shown all over the world. (Ken60)

Why Photos Are Shared

For both our young adults and retirees, a common motivation for photo sharing was to share a memory. For young adults, this motivation was often linked to connecting to friends. They were sharing memories in the sense of posting photos from events where their friends or family had been co-present, including events around their recent life transition of leaving school. For four of the young adults, this theme of sharing photos and memories figured prominently in their stories of why they started using Facebook:

I didn’t get Facebook until… summer 2009. And it’s only because I met a load of good people on holiday. We were at a caravan park…We were all saying goodbye at the end, it was like, ‘Oh, do you have Facebook?’ and I was like, ‘No’. Then I thought, ‘I’ll get it so that we can share photos and things.’(Rebecca21)

For the retirees, sharing a memory could mean sharing photos with family or friends who had been co-present at an event, but it could also mean documenting an event, person, or place to show to absent friends, or for posterity. For example, Douglas60 had posted old family photos to a genealogy website, and a picture of his wife’s father to the Royal Navy website,Footnote8 while another retiree took and posted photos of a special tree-planting ceremony:

Last year there was an assembly in [place name], they planted a coronation tree to celebrate the Queen’s sixtieth anniversary on the throne and there had been a tree planted in 1953, so I was asked to take some photographs and I put them on a website for the people who were there to share. (Donald65)

A common experience for the young adults in photo sharing was that they were tagged in a photo that was shared by someone else on Facebook. Although no retirees reported that others shared photos of them, when we visited their Facebook pages with them, we found that six participants had been tagged in Facebook photos, although it was often one or two photos versus tens or hundreds in which young adults may be tagged.

Digital Personhood

Participants in both groups showed ‘who they were’ through photos online, although this was far more common in young adults than the retirees. The young adults reported sharing photos to ‘let people know what I’ve been up to’, or ‘to keep in touch’. For many of these participants, posting photos almost always took the place of posting a written status update on Facebook. For example:

I uploaded loads when I was in Peru so I think that’s probably the time that I’ve uploaded the most photos…it was like… travel, kind of my entire life in Peru. I wanted to show everyone what it was like really…this was how I’d told my friends and my parents and my family and everything what was going on. When you can’t really talk to people as often, it’s easier just to post lots of photos so they can see. (Megan22)

Three young adults specifically mentioned capturing a sense of their identity as a reason for sharing a photo, for example: ‘One night we were playing Harry Potter Cluedo with wine and cake and I felt, “This is so typical of us” and took a picture…’ (Rebecca21).

Some young adults had mixed feelings about documenting their identity online. For example, Andrew21 deleted ‘a load’ of photos of himself volunteering in Kenya, including several pictures that had formerly been his profile pictures because: ‘…it kind of cheapens the experience if part of your reason for doing something is to then be able to share it and get recognition for it.’ Here, Andrew showed he had clearly been thinking about his online self-representation, but other young adults expressed a similar idea in response to an interview question about seeking likes on social media, with fewer than half our young adult interviewees admitting to posting photos simply to seek ‘likes’.

In terms of photos at the life transition, all of the young adults had one or more photos connected to their Facebook profile of the last day of school, an end-of-school dance, their (or a friend’s) 18th birthday party, and/or a holiday taken with friends after leaving school. For retirees, photos of life transition events – sixtieth birthdays, for example, or retirement parties, were very rare. Only two participants mentioned retirement parties in the interview, and only one had a photo of his party online, perhaps because it connected to another part of his life:

We’ve got a little band, a bunch of neighbours who play Scottish music… and this is my retirement party… And it was a surprise, they turned up in full outfits, I didn’t know they were gonna be there, and we all played together at my retirement party, which was a real hoot. (John69)

Among the retirees, only one participant talked explicitly about portraying himself online through photos:

I put these up. This is me trimming hedge. This is my brother-in-law in Los Angeles…, This is us posing in Santa Monica with our hats. I suppose this is my one attempt at trying to portray myself online. Because when I first set up the Facebook, I put all these on and I haven’t done much since, but just lots of different things I thought people would find interesting. (John69)

Two retirees showed themselves online in humorous ways (Ian60 called these ‘Mickey Mouse profile photos’) or in a context of ‘Me with…’ (for Tom69, with his football hero, and with a cardboard cut-out of President Obama). Two others alluded to ‘being honest’ in photos of themselves shared online, one by updating his profile photo regularly, even on un-used sites like LinkedIn, and another by posting a photo on a dating website even though she declined to post a photo of herself on Facebook.

For retirees who rarely shared photos online, however, the theme of online danger loomed large, with peril associated even with posting a picture of oneself on SkypeFootnote9:

We rapidly discovered that [if my wife] was [pictured] just as herself, she got all sorts of propositions from people, you know, who wanted to be her friend or her contact so … we changed the name so that it’s both of us with a picture of us both… I’ve no illusions as to what they’re looking for, I just block it all. (Douglas60)

Future of Photos in Online Life

When asked about the future of photos in online life, most participants focused on the speed of technological change to explain why it was hard for them to predict what role photos would play in the future. Some of our young adults and retirees believed that photos would still be ubiquitous, but their functions would depend upon what kind of devices and media became common in the future. One retiree participant reflected on what he perceived to be a continuing age-divide with regards to technology:

Youngsters will be growing up taking these things for granted… instant access to anybody wherever in the world they are, being able to – what’s it called? – Snapchat. Instantly send a photograph to somebody wherever they are. …I don’t [take it for granted]…because so little of my life has actually been with that technology. (Ian60)

Other participants focused on the reality that part of their past is documented on Facebook and other sites; several young adults specifically mentioned that this photo-documentation links them to other people, and those links will persist into the future. A few young adult participants thought that they might expand their current photo archives more formally online (storing albums with ‘only me’ privacy settings on Facebook, for example), or completely replacing offline photo albums with digital ones.

Digital images for surveillance and monitoring were also the subject of discussion by both groups. They commented that this future was almost hereFootnote10 with the widespread nature of closed circuit television (CCTV) deployed in the UK. This seemingly ubiquitous CCTV, coupled with the potential unlocked by advancing facial recognition technology, connected even in younger participants’ minds to online danger:

I am sure it will be even fancier in 10 years’ time…. Probably be even easier to upload photos and maybe there’ll even be cameras, every single location in the world that will take a photo for you. And they just upload it straight to Facebook…or maybe face recognition will be like way easier so …even if you are not friends with the person it might immediately come up with who they are…It would be, really awkward for everybody wouldn’t it…that person is in the background [of a photo in a nightclub] but it immediately comes up with their name and it causes a lot of awkwardness for them. They are probably doing something they should not. (Megan22)

This participant – and others who envisioned a future where more could be known about people by expanding access to the kind of information already available online – was quick to point out that she would not like such an auto-upload feature to be used on her, however.

DISCUSSION

This paper has explored photo sharing during two life transitions: leaving secondary school and retiring from work. The findings presented here arguably contribute novel and valuable understanding of digital photographic practices, variations in behaviours across young adults and retirees, and how digital photos serve as expressions of personhood and identity. The findings also offer insight into how young adults may continue to represent themselves through digital photos as they grow older and become retirees themselves.

In this section, we begin to address social norms for digital photo taking and sharing for individuals at different transition points in the human lifespan. We further explain how these norms shape what kind of photo content is shared across life transitions as an expression of digital personhood, and with whom they are shared. We then discuss how young adults and retirees approach balancing convenience and privacy online, and conclude by revisiting the Kodak Culture and Snaprs framework and by theorising future behaviour of young adults, given our current findings.

Photos Taken and Shared: Digital Social Norms for Digital Selves

Although all of our participants took and shared photos, the young adults generally posted more content on social media to communicate their social identities than the retirees did.

For the young adults, photos taken reflected their recent life transition of leaving school – at least those aspects of the transition that were socially experienced: the group ‘last day of school’ photos, final prom event, vacation with friends, milestone birthdays (the age of 18 is associated with leaving school and being able to buy and drink alcohol legally in the UK), arriving at University and making new friends. One participant noted that ‘practically all of the photos of me on Facebook are of social occasions’ (Gavin21) and others explained that even if they did not post such photos themselves, ‘there is always a friend who will’ (Rebecca21) because of the strong digital social norm amongst young adults to share one’s life with friends online.

The photos shared presented portraits of young adults that were co-created with their friends, following a digital social norm on social media that emphasised the co-creation of identity. This co-creation could be consensual, through agreed tagging and shared albums, or illicit – for example through ‘Fraping’, where another person posted material on their Facebook page in their name, without their consent (Moncur, Orzech, and Neville Citation2016). The co-created nature of online identity (or identities) was an accepted norm amongst this group. They also recognised that online identity was an edited (not necessarily accurate) version of self, echoing previous findings by (boyd and Ellison Citation2007; Van Dijck Citation2008) whereby online identities are crafted through a process of impression management to reveal a partial (often favourable) representation of an individual. The crafting of this edited identity was guided by a digital social norm involving a balance between accuracy and approval-seeking, posting pictures of oneself and one’s activities that would be ‘liked’ by friends on social media. Central to many of the photos was the young adult herself/himself, with the camera lens turned inwards, documenting that individual’s participation in events during this transitional period.

Photos taken by retirees did not usually reflect their recent life transition. Participants from this group shared only one retirement party photo on Facebook. For most of the retirees who shared photos, the subjects tended to skew towards where they were (vacations, landscapes) and who they were with (often family, and sometimes friends). There was a focus in shared photos on family, special occasions, vacations, and interests that often skewed the content of photos away from a focus on people. For example, a history buff would take photos of historical sites, a bird-watcher would take photos of unique birds that she saw. One exception was John69’s focus on creating an online persona for Facebook (see above), but most retirees did not articulate a desire to present themselves online in that way. There was a small amount of co-creation of personhood for retirees (for example, family members tagging them in photos on Facebook), but based on our qualitative research, the digital social norm for retirees was to construct their digital personhood (beyond often work-associated things searchable on Google) alone. Their lens was commonly turned outwards, placing them as an observer of experiences, rather than a central actor.

Retirees treated digitally mediated photo sharing as an extension of their previous behaviour – sharing physically printed photos. They did not feel obligated to share online or co-create identity in the way that our young adults did. Their photo sharing behaviour was constrained by potentially more limited peer groups on social networks. It was also constrained by uncertainty about where photos ‘went’ once they were posted online. These practical problems and privacy concerns led retirees to favour the use of named recipients and limited channels (via email and text messages) when sharing photos. Although retirees completed many tasks online, and were drawn to the instant availability of information, social norms around sharing one’s life online reflected that developing and maintaining relationships was mainly an offline activity for them.

There are several possible explanations for why the retirement life transition was photographed less (or at least, shared less) than the leaving secondary school transition. In addition to the possibility that our older participants were less photo-oriented than their younger counterparts (not as prone to snap a picture), several of them were self-employed or working from home, so perhaps they did not have a retirement party. At least two participants had other life circumstances that may have precluded retirement from being a big event (for example, losing their partner around the time of retirement). Finally, parties that did happen may have been enjoyed by retirees in the moment, without them feeling a need to document and share the event.

Balancing Convenience and Privacy

We found variable tensions between convenience and privacy amongst our participants. Previous work has explored these tensions – e.g. (Chin et al. Citation2012; Kolimi, Zhu, and Carpenter Citation2012; Durrant et al. Citation2011), including in the specific context of photo sharing (Ahern et al. Citation2007; Moncur et al. Citation2014). Both groups valued the sense of being connected and being in touch with others that being online brought with it – with the caveat that sometimes they did not want to share their life (or their photo) with everyone. The value of convenience, and the digital social norms of identity co-creation and sharing with friends, won out for most of the young adults over privacy concerns when it came to sharing photos on Facebook, even though they articulated concern about the ever-widening audience of the site. Retirees attributed greater weight to online privacy concerns, and this mostly kept them from sharing on Facebook.

Kodak Culture for All

Despite extant theoretical discussion of the photographic practice of Kodak Culture versus Snaprs, both young adults and retirees in our study still practiced Kodak Culture. They took photos of events like holidays and celebrations, and shared those photos with key people linked to the photo subjects (Chalfen Citation1987), whether that sharing was accomplished on a semi-public platform like Facebook, or more privately through email or a text message attachment. In keeping with the traditions of film photography, both young adults and retirees talked about printing photos, demonstrating their value as tangible reminders.

In addition to practicing Kodak Culture, the young adults also embraced the photography of the everyday and widespread sharing that characterises Snaprs (Miller and Edwards Citation2007; Sarvas and Frohlich Citation2011). We suggest that the theoretical distinction between Kodak Culture and Snaprs is not an either/or situation, but an additive way to understand the ‘social practices around photography’ (Lindley et al. Citation2008), advancing the discourse in visual studies and related fields.

Future of Photo Sharing Technology

When reflecting on the future of photo sharing, participants expressed concern about what would happen to the digital photos that are becoming a ubiquitous means to communicate, irrespective of whether they are casually or carefully shared and stored online. During interviews, young adults and retirees both commented on the fast pace of technology change, and expressed a desire to keep up with this rapid change rather than focusing on deeper issues of how technology is changing human behaviour. While participants in both groups said that they liked browsing on the Internet, they also voiced concern about being the subject of others’ browsing activity, especially in a future where photos may be taken and posted without consent, and where online information (like relationship status) may be even more widely available.

Our evidence, building upon extant research, indicates that digital social norms for young adults are stronger than for retirees, with almost all young adults maintaining friendships and ‘keeping in touch with’ family and friends on Facebook (and also Snapchat and Instagram) (Jang et al. Citation2015; Joinson Citation2008; Mazur and Kozarian Citation2010; Mendelson and Papacharissi Citation2010; Tinkler Citation2008). Consistent with observations by Lee, Goede, and Shryock (Citation2010), photos contribute to young adults’ efforts at keeping in touch as part of an ecology of digital media and metadata, rather than as stand-alone artefacts. For retirees, keeping in touch online is less expected because, unlike young adults, retirees have not been engaged in such practices since their early adolescence. Communication by phone or email is socially acceptable, and it is not assumed that every communication must be illustrated (Hope, Schwaba, and Piper Citation2014).

Both young adults and retirees may also be choosing their preferred communication channel based on the recipient of the communication, going on Facebook because friends or family are there, or choosing to video chat or email with particularly close contacts (see Bales and Lindley Citation2013 for a discussion of this among University students). As young adults age, we suggest that they will continue to engage in their existing digital photo practices because the norm of visually ‘keeping in touch’ will likely continue to be a digital social norm for those individuals.

Both of our participant groups viewed the spread of the Internet and digital photos positively – allowing them to be connected, keep in touch, and have information at their fingertips. However, they did not want to be browsed in the same way they browse others. Jiang and colleagues (Citation2013) explore how common latent interactions are on a Chinese social network, but future research might address people’s actual browsing activities as well as their perceptions of ‘who’ browses them on social media. As young adults grow older, there may be a browsing-related backlash, where users demand more protected browsing – or at least more information about who is browsing them.

Our findings suggest that, in the future, retirees are likely to have a longer history of technology adoption behind them than most of the retirees who took part in our study did. They may be more ‘tech-savvy’ as a result. The retirees in our study were born long before the Internet was widely used. What we can learn from our sample of retirees is that they are generally more concerned with sharing their lived experiences of the world that they inhabit, for example, through photos of architecture, knitting, bird-watching; the camera’s lens is usually turned outwards towards the world, not inwards to the individual. We anticipate that future retirees are likely to be sensitised to the growing list of digital social norms prevalent online, although these are likely to evolve over time with the incessant advent of new technologies. The volume of photo posting common amongst young adults may well slow down, as privacy concerns develop along with maturity, and egocentricity gives way to outward-looking interests in family and community. It is certain that participants’ world views will continue to shape their use of digital technology, just as digital technology continues to shape their world views. Finally, our findings suggest that both young and old will retain a hypocritical stance when it comes to browsing others online. Just like offline gossip, people are happy to do it, but not so happy to be the subject of it themselves.

CONCLUSION

This paper extends the established discourse about the social function of photography as a medium for self-expression and identity management in a digital context, as well as the mechanics of sharing photos. It does this by detailing the photo taking and sharing practices in two life transition groups: young adults leaving secondary school; and older adults who have recently retired from work. To support our claim herein that Kodak Culture and Snaprs may not be such a binary distinction, we have drawn upon our ethnographic and photo-classification research among research participants at these two life transitions. We found that both groups photographed similar subjects and wanted to share photos for similar reasons, but that the young adults used shared photos as part of their self-expression far more readily and at greater volume than the retirees. The young adults regularly constructed their digital identities and digital personhood using photos they posted combined with photos posted by others. The use of photos to express a sense of self was not absent in retirees, but they were much more careful and considered about their digital identity. This attitude toward digital personhood may affect photo sharing in the future, although desire for convenient access to knowledge and connection with others – especially at key transition points in the human lifespan – may ultimately outweigh concerns for privacy and a carefully curated presentation of self.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kathryn M. Orzech

Dr. Kathryn M. Orzech is a research fellow interested in how online life and connectivity change across the physical lifespan. Her research focuses on the intersections of anthropology, digital technology, and health.

Wendy Moncur

Dr Wendy Moncur holds an Interdisciplinary Chair in Digital Living at the University of Dundee, where she leads the Living Digital group. Her interdisciplinary research focuses on the design of digital technologies to support lived human experience across the lifespan, and is grounded in Human-Computer Interaction.

Abigail Durrant

Dr. Abigail Durrant is Associate Professor and Leverhulme Fellow in the School of Design at Northumbria University, UK. Her research primarily explores the design of digital systems and services to support the expression of selfhood and identity, focusing on the use of photographic media and engaging visual methods. Abigail’s fellowship work investigates how design research can deliver transferrable value within interdisciplinary project teams.

Stuart James

Dr. Stuart James is a Research Fellow in Visual Information Retrieval. His research focuses on visual big-data-driven machine learning problems applied to a variety of fields including Human-Computer Interaction and Digital Humanities.

John Collomosse

Dr. John Collomosse is a Reader (Assoc. Prof.) within CVSSP at the University of Surrey and a Visiting Professor at Adobe Systems, San Jose (CA). His research fuses Computer Vision, Graphics and Machine Learning to tackle Big Data problems in visual media, with particular emphasis on post-production in the creative industries and intelligent algorithms for searching and rendering large visual media repositories.

Notes

[1] www.facebook.com.

[2] For example, when you become friends with someone, you expect that they will visit your profile and comment on it.

[3] https://twitter.com/.

[10] This ‘future’ is in fact already here, see Taigman,Yaniv, Ming Yang, Marc’Aurelio Ranzato, & Lior Wolf. 2014. ‘Deepface: Closing the gap to human-level performance in face verification.’ In Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2014 IEEE Conference, 1701–1708. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2014.220.

REFERENCES

- Ahern, S., D. Eckles, N. S. Good, S. King, M. Naaman, and R. Nair. 2007. “Over-Exposed?: Privacy Patterns and Considerations in Online and Mobile Photo Sharing.” In Proceeding of CHI’07, 357–366. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/1240624.1240683.

- Apted, T., J. Kay, and A. Quigley. 2006. “Tabletop Sharing of Digital Photographs for the Elderly.” In Proceeding of CHI’06, 781–790. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/1124772.1124887.

- Baecker, R. M., K. Moffatt, and M. Massimi. 2012. “Technologies for Aging Gracefully.” Interactions 19 (3): 32–36. doi:10.1145/2168931.2168940.

- Bales, E. S., and S. Lindley. 2013. “Supporting a Sense of Connectedness: Meaningful Things in the Lives of New University Students.” In Proceedings of CSCW’13, 1137–1146. New York: ACM. doi:10.1145/2441776.2441905.

- Botticello, J., T. Fisher, and S. Woodward. 2016. “Relational Resolutions: Digital Encounters in Ethnographic Fieldwork.” Visual Studies 31 (4): 289–294. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2016.1246350.

- boyd, d. m., and N. B. Ellison. 2007. “Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13 (1): 210–230.

- Burke, M., and R. Kraut. 2013. “Using Facebook after Losing a Job: Differential Benefits of Strong and Weak Ties.” In Proceedings of CSCW’13, 1419–1430. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/2441776.2441936.

- Chalfen, R. 1987. Snapshot Versions of Life. Bowling Green, OH: Popular Press.

- Chalfen, R. 2009. “‘It’s Only a Picture’: Sexting, ‘Smutty’ Snapshots and Felony Charges.” Visual Studies 24 (3): 258–268. doi:10.1080/14725860903309203.

- Charmaz, K. 2011. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Chekroun, P. 2008. “Social Control Behavior: The Effects of Social Situations and Personal Implication on Informal Social Sanctions.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2 (6): 2141–2158. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00141.x.

- Chin, E., A. P. Felt, V. Sekar, and D. Wagner. 2012. “Measuring User Confidence in Smartphone Security and Privacy.” In Proceedings of the Eighth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security, SOUPS ’12, 1:1–1:16. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/2335356.2335358.

- Collomosse, J., S. James, A. Durrant, D. Trujillo-Pisanty, W. Moncur, K. M. Orzech, S. Martindale, and M. Chantler. 2014. “Enhancing Digital Literacy by Multi-Modal Data Mining of the Digital Lifespan.” In Digital Economy 2014. London, UK.

- Durrant, A., A. S. Taylor, D. Frohlich, A. Sellen, and D. Uzzell. 2009. “Photo Displays and Intergenerational Relationships in the Family Home.” In British Computer Society Conference on Human Computer Interaction ’09, 10–19. Swinton, UK.

- Durrant, A., D. Frohlich, A. Sellen, and D. Uzzell. 2011. “The Secret Life of Teens: Online versus Offline Photographic Displays at Home.” Visual Studies 26 (2): 113–24. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2011.571887.

- Emanuel, L., and D. S. Fraser. 2014. “Exploring Physical and Digital Identity with a Teenage Cohort.” In Proceedings of IDC ’14, 67–76. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/2593968.2593984.

- Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. 2015. “Skills: Priority Areas: Digital Identity.” Digital Identity. https://www.epsrc.ac.uk/skills/students/centres/2013cdtexercise/priorityareas/diid/.

- Fleming, S. E., R. Vandermause, and M. Shaw. 2014. “First-Time Mothers Preparing for Birthing in an Electronic World: Internet and Mobile Phone Technology.” Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 32 (3): 240–253. doi:10.1080/02646838.2014.886104.

- Foresight Future Identities. 2013. “Future Identities: Changing Identities in the UK: The Next 10 Years.” Final Project Report. London: Government Office for Science. http://www.bis.gov.uk/foresight/our-work/policy-futures/identity

- Frohlich, D., A. Kuchinsky, C. Pering, A. Don, and S. Ariss. 2002. “Requirements for Photoware.” In Proceedings of CSCW’02, 166–175. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/587078.587102.

- George, L. K. 1993. “Sociological Perspectives on Life Transitions.” Annual Review of Sociology 19 (January): 353–373.

- Goffman, E. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City, NY: Double Day.

- Graham, C., E. Laurier, V. O’Brien, and M. Rouncefield. 2011. “New Visual Technologies: Shifting Boundaries, Shared Moments.” Visual Studies 26 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2011.571883.

- Harrison, B. 2002. “Photographic Visions and Narrative Inquiry.” Narrative Inquiry 12 (1): 87–111. doi:10.1075/ni.12.1.14har.

- Hope, A., T. Schwaba, and A. M. Piper. 2014. “Understanding Digital and Material Social Communications for Older Adults.” In Proceedings of CHI’14, 3903–3912. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/2556288.2557133.

- Hulme, A. 2014. “Next Steps: Life Transitions and Retirement in the 21st Century.” Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. http://gulbenkian.org.uk/files/01-07-12-Next%20steps%20-%20Life%20transitions%20and%20retirement%20in%20the%2021st%20century.pdf.

- James, S., and J. Collomosse. 2016. “Evolutionary Data Purification for Social Media Classification.” In Proceedings of ICPR'16, 2676–2681. New York, NY. IEEE. doi:10.1109/ICPR.2016.7900039

- Jang, J. Y., K. Han, P. C. Shih, and D. Lee. 2015. “Generation Like: Comparative Characteristics in Instagram.” In Proceedings of CHI ’15, 4039–4042. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/2702123.2702555.

- Jiang, J., C. Wilson, X. Wang, W. Sha, P. Huang, Y. Dai, and B. Y. Zhao. 2013. “Understanding Latent Interactions in Online Social Networks.” ACM Trans. Web 7 (4): 18:1–18:39. doi:10.1145/2517040.

- Joinson, A. N. 2008. “Looking At, Looking up or Keeping up with People?: Motives and Use of Facebook.” In Proceedings of CHI’08, 1027–1036. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/1357054.1357213.

- Kolimi, S., F. Zhu, and S. Carpenter. 2012. “Is Older, Wiser?: An Age-Specific Study of Exposure of Private Information.” In Proceedings of ACM-SE’12, 30–35. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/2184512.2184520.

- Kuhn, A. 2007. “Photography and Cultural Memory: A Methodological Exploration.” Visual Studies 22 (3): 283–292. doi:10.1080/14725860701657175.

- Lee, D. B., J. Goede, and R. Shryock. 2010. “Clicking for Friendship: Social Network Sites and the Medium of Personhood.” MedieKultur. Journal of Media and Communication Research 26 (49): 137–150.

- Lindley, S. E., A. C. Durrant, D. S. Kirk, and A. S. Taylor. 2008. “Collocated Social Practices Surrounding Photos.” In CHI ’08 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 3921–3924. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/1358628.1358957.

- Lindley, S. E., R. Harper, and A. Sellen. 2009. “Desiring to Be in Touch in a Changing Communications Landscape: Attitudes of Older Adults.” In Proceedings of CHI’09, 1693–1702. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/1518701.1518962.

- Luttrell, W., and R. Chalfen. 2010. “Lifting up Voices of Participatory Visual Research.” Visual Studies 25 (3): 197–200. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2010.523270.

- Madden, M., A. Lenhart, M. Duggan, S. Cortesi, and U. Gasser. 2013. “Teens and Technology 2013.” Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. March. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/03/13/teens-and-technology-2013/

- Massimi, M., R. Harper, and A. J. Sellen. 2014. “‘Real, but Glossy’: Technology and the Practical Pursuit of Magic in Modern Weddings.” In Proceedings of CSCW’14, 854–865. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/2531602.2531682.

- Mazur, E., and L. Kozarian. 2010. “Self-Presentation and Interaction in Blogs of Adolescents and Young Emerging Adults.” Journal of Adolescent Research 25 (1): 124–144. doi:10.1177/0743558409350498.

- Mendelson, A. L., and Z. Papacharissi. 2010. “Look at Us: Collective Narcissism in College Student Facebook Photo Galleries.” In The Networked Self: Identity, Community and Culture on Social Network Sites, edited by Z. Papacharissi. New York: Routledge.

- Miller, A. D., and W. K. Edwards. 2007. “Give and Take: A Study of Consumer Photo-Sharing Culture and Practice.” In Proceedings of CHI’07, 347–356. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/1240624.1240682.

- Moncur, W., L. Gibson, and D. Herron. 2016. “The Role of Digital Technologies During Relationship Breakdowns.” In Proceedings of CSCW'16, 371–382. New York, NY, USA: ACM. doi:10.1145/2818048.2819925.

- Moncur, W., K. M. Orzech, and F. G. Neville. 2016. “Fraping, Social Norms and Online Representations of Self.” Computers in Human Behavior 63: 125–31. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.042.

- Moncur, W., J. Masthoff, E. Reiter, Y. Freer, and H. Nguyen. 2014. “Providing Adaptive Health Updates across the Personal Social Network.” Human–Computer Interaction 29 (3): 256–309. doi:10.1080/07370024.2013.819218.

- Pauwels, L. 2015. Reframing Visual Social Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. /core/books/reframing-visual-social-science/39757AA22DE47B8C67B59B1ADAC4A7AF.

- Pink, S. 2013. Doing Visual Ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/doing-visual-ethnography/book237694.

- Radley, A. 2010. “What People Do with Pictures.” Visual Studies 25 (3): 268–279. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2010.523279.

- Rainie, L., and B. Wellman. 2012. Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Rose, G. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. 4 ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Sarvas, R., and D. M. Frohlich. 2011. “From Snapshots to Social Media - The Changing Picture of Domestic Photography.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work. London Limited: Springer. http://www.springer.com/computer/hci/book/978-0-85729-246-9

- Schensul, S. L., J. J. Schensul, and M. D. LeCompte. 1999. Essential Ethnographic Methods: Observations, Interviews, and Questionnaires. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Siibak, A. 2009. “Constructing the Self through the Photo Selection - Visual Impression Management on Social Networking Websites.” Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 3 (1). http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2009061501&article=1.

- Smith, A. 2014. “Older Adults and Technology Use.” Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. April. http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/03/older-adults-and-technology-use/

- Sontag, S. 1977. On Photography. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux.

- Stefanone, M. A., and D. Lackaff. 2009. “Reality Television as a Model for Online Behavior: Blogging, Photo, and Video Sharing.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14 (4): 964–987. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01477.x.

- Strauss, A. L., and J. M. Corbin. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Tinkler, P. 2008. “A Fragmented Picture: Reflections on the Photographic Practices of Young People.” Visual Studies 23 (3): 255–266. doi:10.1080/14725860802489916.

- Tufekci, Z. 2008. “Grooming, Gossip, Facebook and Myspace.” Information, Communication & Society 11 (4): 544–564. doi:10.1080/13691180801999050.

- Twenty Pixels. 2013. “Pictures We Didn’t Take before Digital Cameras.” 20px - Twenty Pixels, March 15. http://20px.com/blog/2013/03/15/pictures-we-didnt-take-before-digital-cameras/

- Van Dijck, J. 2008. “Digital Photography: Communication, Identity, Memory.” Visual Communication 7 (1): 57–76. doi:10.1177/1470357207084865.

- Van Dijck, J. 2011. “Flickr and the Culture of Connectivity: Sharing Views, Experiences, Memories.” Memory Studies 4 (4): 401–415. doi:10.1177/1750698010385215.

- Waycott, J., F. Vetere, S. Pedell, L. Kulik, E. Ozanne, A. Gruner, and J. Downs. 2013. “Older Adults As Digital Content Producers.” In Proceedings of CHI’13, 39–48. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/2470654.2470662.

- Weiss, R., and C. P. Samenow. 2010. “Smart Phones, Social Networking, Sexting and Problematic Sexual Behaviors—A Call for Research.” Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity 17 (4): 241–246. doi:10.1080/10720162.2010.532079.