Abstract

The popularity of sharing photographs on digital platforms has increased significantly due to the communicative affordances of mobile media and the emergence of photo-sharing applications, such as Instagram. In this paper, we examine how social support and communality can be built and reinforced through digital visual communication. We focus especially on photo sharing in the context of recreational climbing and trail running. In a qualitative study with Finnish climbers and runners, we asked what meanings sports practitioners ascribe to the practice of sharing and observed how they communicate these meanings through photographs. The results indicate that different types of visual content build and reinforce communality in distinct ways. Whereas inspirational photographs drive practitioners to explore, motivational photographs pull practitioners to keep going through goal setting and peer support. We conclude that visual communication on Instagram mediates a stream of momentary encounters between practitioners that merge into communally meaningful experiences. Thus, we assert that in the context of recreational sport subcultures, photo sharing not only facilitates social relationships but can be perceived as a meaningful social practice that is integral to reinforcing physical activity.

INTRODUCTION

Photography has always been inherently tied to sharing (Lobinger Citation2016). With the rise of social media, the popularity and ease of sharing photographs has increased significantly. The key reasons for this are the communicative affordances of camera phones (Villi Citation2010) and the emergence of photo-sharing applications, such as Instagram. Today’s ubiquitous mobile devices and applications can be said to ‘push individuals to think visually of events, people and surroundings’ (Serafinelli and Villi Citation2017, 165). As user statistics of photo-sharing applications demonstrate, we are witnessing an extraordinary phase in the history of photography: Instagram alone has over a billion global users (Systrom Citation2018), who share more than 100 million photographs and videos, on average, every day (Aslam Citation2020). Yet photo sharing can also lead to unwanted consequences, such as loss of privacy (Serafinelli and Cox Citation2019) and the social media platforms’ commoditisation of relationships (van Dijck Citation2013).

Recreational sport provides a rather unexplored yet important context for the study of visuality. Images of sport in general have historically been an integral part of visual cultural production (Finn Citation2014). In addition, sport-related visual content has become increasingly popular on social media in recent years (Thorpe Citation2017), as not only professional athletes but also recreational practitionersFootnote1 share photographs and videos of themselves participating in sports. Practitioners create educational, experiential, and entertaining visual content both for their own consumption and for others with similar interests. Sharing one’s physical performance visually can make practitioners feel connected; for them, photography is a connective interface (Gómez Cruz Citation2016). However, what exactly makes visual communication online evoke a feeling of connectedness has not been studied intensively.

In this paper, we examine how recreational climbers and trail runners can build and reinforce a sense of communality by sharing photographs on Instagram. To that end, we ask what meanings practitioners ascribe to photo sharing and we observe how they communicate these meanings through photographs. We understand meaning making as a hybrid outcome of individual interpretations and interpersonal and cultural negotiations of life events and objects. According to Lomborg (Citation2015, 1), meaning making ‘evolves in the meeting between the communicative potentials and constraints of a text or a medium and individuals’ pre-existing mental modes, expectations and intentions in context’. To analyse meaning making, the present study focused on Instagram as a platform, the practice of photo sharing, and shared photographs. The results shed light on how photo sharing can be used to create communality among social media users.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Sharing photographs online or in other ways fulfils different purposes in different contexts and for different people. Lobinger (Citation2016) differentiates between three modes of photo sharing: (1) sharing photographs to talk about images, focusing on the situation or context that occurred when a photograph was taken; (2) sharing photographs to talk with the images, meaning to communicate something visually; and (3) sharing photographs to maintain connections, meaning the practice of phatic photo sharing that Lobinger (Citation2016, 481) defines as sharing ‘for the sake of visual connectivity and thus in order to confirm and strengthen bonds and relationships’ (see also Villi Citation2010). According to Lobinger (Citation2016), these three photo-sharing modes are situational – that is, people rapidly switch between different modes depending on their circumstantial purposes and needs.

Studies on online and mobile visual communication highlight that when it comes to creating connections or communality through photographs, the practice of phatic photo sharing is of utmost importance. In his study on visual mobile communication, Villi (Citation2012) shows that mobile phone users share photographs primarily to maintain connections in a ritual manner. He argues that phatic photo sharing stems from the practices of mobile (telephone) communication and is best understood as a habitual act between users.

Similarly, in her study on the use of photographs in transnational families, Prieto-Blanco (Citation2016) shows that for physically distant family members, the act of sharing photographs through digital platforms is as important as, or even more important than, the content of the photographs. She argues that family members engage in phatic communication in search of immediacy and closeness despite physical distance, and she concludes that phatic communion ‘opens up space for further and deeper interaction’ (Prieto-Blanco Citation2016, 14). Likewise, regarding visuality on Instagram, Serafinelli (Citation2017) argues that the practice of photo sharing is not socially deeply meaningful as such but should be perceived as an activator of deeper social interaction and relationships. Her research shows that users may create initial social connections by sharing photographs on Instagram; however, rather than using the platform to maintain their relationships, they tend to subsequently move to other social media platforms or face-to-face settings.

In the context of sport, visuality is often studied and seen as an extension of the physical experience. Research shows that recreational sports practitioners use photo-sharing practices to engage in the collective reproduction of style (Woermann Citation2012), assert their place as part of the sports community (Olive Citation2015), and curate their athletic self-presentation (Gray et al. Citation2018). Regarding community building among mountain bikers, McCormack (Citation2018) argues that mediated rituals, such as photo sharing, extend and strengthen social relations between practitioners. More specifically, on the role of photo sharing in building communality, McCormack (Citation2018, 573) concludes as follows:

The necessity of telling those [visual] stories, which are stories of technical accomplishment but also of friendship and community, suggests the centrality of these [social media] platforms for creating, sharing, and strengthening the ties between participants.

These notions of the importance of visual stories indicate that sports practitioners share photographs online to talk with and about the images and, consequently, strengthen their interpersonal ties. This partially contradicts other studies (Prieto Blanco Citation2016; Villi Citation2010) advancing the view that it is predominantly the element of phatic communication that creates connection and communality between users on the more intimate digital platforms (e.g. visual messaging and WhatsApp).

In this paper, we examine what roles phatic communication and communicating visual stories play in building communality online, particularly in the context of recreational sport. Moreover, we contribute to the discussion on whether visuality online is merely an activator of social relationships or can be seen meaningfully as such. Thus, the key contribution of this paper to visual studies lies in the study of meaning making and communality in online photo sharing. The paper addresses the following research question: How do recreational sports practitioners exchange social support and build communality through photo-sharing practices online?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data for this study consist of interviews with 10 Finnish recreational sports practitioners, five of whom practise climbing and five trail running as their main sport, and 165 Instagram photographs posted by the interviewees. These recreational sports were selected because both disciplines have a long tradition of practice, they have gained popularity in recent years, they are practised around the globe, and they have a visible presence online. Moreover, in contrast to team sports, where practitioners form a well-defined entity and regularly meet face-to-face, individual or solitary sports practitioners may more frequently lack a sense of belonging and connection with other practitioners. Thus, they may be more inclined to seek alternative ways of connecting with peers, such as through photo sharing.

Participants were recruited through an online survey that had been used for another case study in 2016. The study (Ehrlén Citation2017) investigated climbers’ and trail runners’ communication practices, social tie formation, and social support exchange in online and offline settings. At the end of the survey, participants were asked about their willingness to take part in further interviews regarding social and visual media use related to physical activity. Separate consent forms concerning interview and observation guidelines were sent to all participants after an initial email exchange and prior to data collection. Permission to observe participants’ Instagram accountsFootnote2 and use their photographs in scientific publications was obtained via email.

Data analysis () utilised Schreiber’s (Citation2017) framework for analysing visual communication on social media. The framework accounts for practices, photographs, and platforms as three relevant dimensions for analysis. According to Schreiber (Citation2017), a multidimensional approach is needed to bring out the relevance, meaning, and communicative context of visual data (see also Lobinger Citation2016). At the same time, visual data can draw out meanings that are difficult to put into words (Rose Citation2014). Schreiber’s (Citation2017) general framework was accompanied by Schreier’s (Citation2014) detailed guide for analysing interview data and Grittmann and Ammann’s (Citation2009) approach for analysing meaning in photographs.

FIGURE 1. Analytical framework adapted from Schreiber (Citation2017)

Semi-structured interviews with the 10 participants were conducted in February–April 2017. The participants’ age range was 24–45 years, and they included six male and four female practitioners. Interview data were analysed inductively using qualitative content analysis according to Schreier’s (Citation2014) model.

Qualitative content analysis of the interview data identified four main categories of meanings that practitioners ascribe to photo sharing: inspiration, motivation, information, and identity. All categories emerged inductively from the data. The four main categories included three to six subcategories specifying what made sharing photographs inspirational, motivational, informational, or identity-related. In the first round of coding, there was a fifth additional main category of togetherness that was merged with motivation before the final coding because the categories overlapped considerably. The four main categories of meanings are elaborated in .

TABLE 1. Descriptions of the main coding categories.

Instagram was chosen as the platform for observing photo sharing because it emerged during the research interviews as a widely used mobile application among practitioners. Whereas the interview data were used to identify meanings that practitioners ascribe to visual communication, observation data were used to demonstrate how these meanings manifest through actual photographs.

Practitioners’ Instagram accounts were observed for one month in the spring of 2017 and again for one month in the summer. Observation was limited to photographs that participants posted about their sport-related activities. A photograph was included in the data if it, the related caption, or used hashtags indicated sport-related activities. Only photographs that appeared in participants’ feeds were included in the data collection; that is, Instagram stories (content that disappears after 24 hours) were not observed. Captions and hashtags of the selected photographsFootnote3 were studied via qualitative content analysis (Schreier Citation2014) and categorised deductively into the categories that emerged from the interview data. As comments from other practitioners were often limited to emojis or simple phrases, such as ‘lovely’ or ‘well done’, they did not provide rich textual data and were, thus, left out of the analysis.

The 165 photographs were analysed using image type analysis (Grittmann and Ammann Citation2009). Image type analysis is based on Panofsky’s (Citation1972) iconographical approach. Rather than just classifying photographs, image type analysis goes deeper into analysing social and cultural meanings that photographs bear and interpreting their intrinsic values and ideas (Grittmann Citation2014). An image type emerges when an overreaching idea repeatedly appears in the material (Grittmann and Ammann Citation2009).

The analysis procedure included five stages. First, the first author created a file for each Instagram post. Each file included one or more photographs, captions, hashtags, and comments from other users. The first author inspected all files thoroughly before conducting the image type analysis to get an overview of the data and comprehend each photograph in its original context. Second, the first author created a list of 10 potential image types and categorised all photographs by type. At this point, a photograph could represent one or more image types. Image types were named so as to describe the focal ideas in the photographs. Captions and hashtags were used to confirm the ideas in the photographs and, thus, to define the image types. Third, the authors reviewed all image types together and reduced their number to six. Additionally, the authors labelled eight photographs ‘undefined’ because they portrayed motifs that were not visible in any of the other studied photographs. Fourth, the first author recategorised all photographs under the remaining six image types. At this point, each photograph was categorised under one image type only. When there was uncertainty about the image type, captions and hashtags were inspected more thoroughly. Fifth, the authors examined the image types in relation to the interview categories to understand how the practitioners visually communicate the meanings that they ascribe to photo sharing. Finally, Instagram as a platform was descriptively analysed. Platform analysis (see Schreiber Citation2017) accounted for the structural elements, defaults, and interfaces of Instagram. The analysis was intended to reveal the communicative affordances that shape how participants use Instagram. For the purpose of the overreaching analysis, the three analytical dimensions were finally brought together.

provides an overview of the image types and their respective quantities. The analysed photographs are divided into two main groups: they convey either inspiration or motivation. Most photographs are categorised as inspirational because they portray motifs that the practitioners named in their interviews while discussing photo sharing as a source of inspiration. Likewise, photographs are categorised as motivational when they portray motifs that the practitioners named in their interviews while discussing photo sharing as a source of motivation. Many photographs also provide information or communicate one’s identity. However, upon examining the photographs together with their captions and hashtags, it became clear that participants were not using the photographs solely for information sharing or identity building but that these are by-products of sharing inspiration or motivation. Therefore, we do not discuss information sharing and identity construction as thematic entities but as overreaching themes in the analysis.

Such categorisation of image types is strongly supported by Hinch and Kono’s (Citation2018) analysis of ultramarathon runners’ perception of place. They identify nature, competition, community, and introspection as four themes that the runners photographed during sport-related travel. The only image type that is not clearly visible in their study is ‘lifestyle reflection’. The results of Hinch and Kono (Citation2018) study are reflected throughout the following analysis.

In our analysis, we discuss the interview and observation data in parallel. We go through the data one image type at a time and present illustrative examples and explanatory extracts from the interviews.Footnote4 The analysis begins with a discussion of the role of inspirational photographs and moves on to explore the role of motivational photographs in sports practitioners’ Instagram use. In our study context, inspiration can be seen as a driving force and motivation a pulling force. We distinguish between these two categories because the interviews revealed that the practitioners experience social support emerging from both directions. The difference between these categories is discussed in detail in the following analysis.

RESULTS

Inspiration

The main reason why participants follow others and share photographs on Instagram is to inspire and be inspired by other practitioners. Inspiration is evoked through photographs that portray either nature or athletic performance.

Nature description

shows a typical example of the first image type, called ‘invitation to nature’. It is taken from the practitioner’s perspective in the course of sport practice. The photograph depicts a sunny day in a forest and a path leading to the horizon. It invites the viewer to observe the landscape and imagine taking the position of the practitioner in the quiet beauty of the moment. Other photographs in this category feature landscapes of forest, water, rock, and snow. There is often abundant space and a horizontal line with a clear blue sky visible in the photographs.

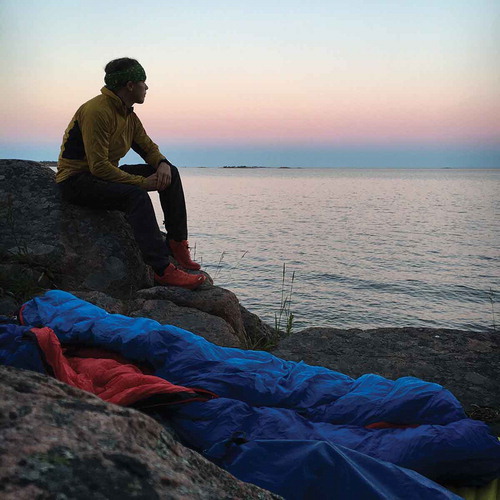

Apart from landscape photographs, nature is depicted in another image type called ‘lifestyle reflection’. A typical example of this type () features a practitioner sitting alone on a stone by the water. The practitioner is looking at the sunset on the horizon and reflecting on the immediate surroundings. There is an open sleeping bag in the foreground, indicating that the practitioner will spend the night outdoors. The photograph conveys the idea of sport as a lifestyle that reaches beyond the physical practice and affects daily life activities. Other photographs in this category feature other accommodations, such as a tent or a van, or practice-related gear, such as a rope, shoes, or backpack in nature. These items are displayed together or without the practitioner. If the practitioner is visible, they are in a still position and are most often portrayed as camouflaging and, thus, belonging to the natural surroundings. As in Hinch and Kono (Citation2018) study, the display of nature in the lifestyle and landscape photographs is portrayed as sublime.

By describing nature through photographs, practitioners inspire each other to explore new surroundings. In the interviews, climbers and trail runners said that they use Instagram to get inspiration or concrete ideas for locations for their practice. Likewise, practitioners share nature photographs on Instagram to inspire others. A 38-year-old climber, Peter,Footnote5 described this as follows:

It doesn’t matter whether it’s climbing or travelling. What I like about social media is that when people post [photographs], I get ideas like ‘maybe should I go there?’ … For me, it’s about whether someone can benefit from [my photographs] in a way that they stimulate ideas.

For Peter, climbing and travelling are closely related. Data from other interviewees, as well as other studies (e.g. Getz and McConnell Citation2014; Rickly-Boyd Citation2012), confirm that trail runners and climbers often combine leisure travel with sport practice. Importantly, instead of looking for sources of travel inspiration from commercially produced media, practitioners make use of user-generated visual content on Instagram. For 32-year-old trail runner Jesse, photographs have a pivotal role in determining travel destinations:

The way I plan my future practice or running events I want to participate in … Often I first look at the photos, what kind of landscapes there are … For me, it’s a part of the motivation in trail running that I can run in such places where I wouldn’t go otherwise. The landscape and the surroundings, and that you practice in nature … It’s a show of its own.

Jesse’s description indicates that he feels connected to the natural surroundings where he practices. Sport-related literature (e.g. Bale Citation2003; Hinch and Kono Citation2018) suggests that physical activity gives meaning to places. Consequently, by sharing a place visually, practitioners can also share their connection to the place with others. Simultaneously, mobile phone photography changes the understanding of physical surroundings because they are constantly mediated through phone screens (Serafinelli and Villi Citation2017). Thus, an established and shared connection to a specific place is both a physical and a mediated experience of the surrounding nature.

Instagram allows users to tag their photographs and videos with a specific location (for early accounts on location-based media, see e.g. Lapenta Citation2011). Eighty-five per cent of all analysed photographs include location information in the captions or used hashtags. In line with previous research (e.g. Olive Citation2015), this shows that revealing one’s geographic location is an important part of climbers’ and trail runners’ photo-sharing practices. Villi (Citation2016) argues that mobile phones’ location-aware aspects not only mediate physical but also social presence. Therefore, as a viewer of a photograph, one can experience ‘being there and with you’.

Using landscape photographs, practitioners not only share information about the location but also about the conditions at a specific sports site. A 32-year-old climber, Tomas, explained:

I seek inspiration from Instagram and I use it to study … Ice climbing is very sensitive to conditions, and it’s nice to know what the situation is at different sites in Southern Finland. Instagram lets me know, for instance, that ‘ah, someone climbed there a week ago – cool – so it should be in good condition’.

According to the interviewed climbers and runners, open information sharing strengthens communality among them. Tomas also expressed what it means for him to be able to share knowledge and inspire others:

A friend of mine wrote to me a while ago that he saw a photo I’d posted about a climbing site we had been to, and they got enthusiastic about it. The night after I posted it on Instagram, I got a message: ‘Cool, we saw your photo and the conditions were good there, and we went there the day after’. For me, it was like ‘okay, now this hits home; this is what I wanted to do’.

Like Tomas, many participants conveyed the joy of inspiring others through visual media. Thus, reciprocity is a key value that guides recreational sports practitioners’ Instagram use (see Serafinelli and Villi Citation2017). Practitioners seek out sources of inspiration and information that benefit them while carefully weighing what kind of information would be beneficial for others. This shows that informational support (see Berkman et al. Citation2000) is an important form of social support in trail runners’ and climbers’ photo-sharing practices.

Moreover, by sharing lifestyle photographs, practitioners construct a common identity and idea of what it means to be a practitioner of lifestyle sport. By definition, lifestyle sport is about practitioners’ holistic orientation towards the practice (see Wheaton Citation2010). One of the core values of lifestyle sport is being out in the wilderness (see van Bottenburg and Salome Citation2010). For 45-year-old trail runner Matias, communality in lifestyle sport arises among ‘like-minded people who value nature as they value their physical condition’. Lifestyle photographs reinforce these values and symbolise practitioners’ connection to nature.

Besides constructing a shared identity, practitioners use lifestyle photographs to build and communicate their personal identity. The default setting on Instagram enables anyone to see a user’s profile and posts. Only one participant had limited his audience by making his profile private. Sharing lifestyle photographs to a larger community of practitioners may partly be an attempt to give an impression that one is a lifestyle sport practitioner and, thus, constitute an effort to belong to the community.

Using Instagram, practitioners can depict how a sporting lifestyle is connected to and guides many aspects of their everyday lives. A 36-year-old trail runner, Isla, elaborated:

I hope I can inspire others, because I get so inspired by what others do. The places where people have been and their everyday lives … I’ve noticed that sometimes when I think ‘this is probably nothing; it’s something mundane’ … For someone else, it might be inspiration for something.

As Isla noted, the small act of sharing a photograph can have large or unexpected effects. Thus, inspirational photographs have a driving force: they attract the viewer to explore.

Through visual communication, practitioners inspire each other to explore their external surroundings as well as their internal worlds and to negotiate the limits of their individual and shared lifestyle sport identities. In this process, they exchange appraisal support, which is useful feedback for self-evaluation (see Langford et al. Citation1997). By recurrently describing nature through photographs, practitioners strengthen common values and reflect their relation to the sport and to the natural surroundings that enable their practice.

Athletic performance

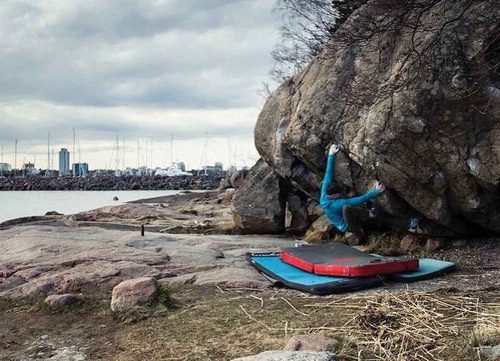

Inspiration is also conveyed through photographs that portray athletic performance. shows a typical example of the third inspirational image type, ‘in action’. It features a deeply focused climber bouldering on a rocky shore. The photograph represents a strong, capable, and disciplined athlete’s body in practice. Similarly, other photographs in this category feature climbers and trail runners practising in landscapes that are often picturesque. In contrast to image types depicting the tranquillity of nature, photographs in this category illustrate movement and vibrancy. People in the photographs are either portrayed as practising alone or with others.

Sharing photographs of their physical practice allows practitioners to visually demonstrate what they are capable of. Climbers and trail runners said that they typically share photographs if their practice has been remarkable. A 31-year-old trail runner, Anton, elaborated:

Often, when I take photos, they are either about a tough or a long workout. The practice itself was special in some way. Like, if I run four kilometres in the morning, it’s not something I post.

Posting photographs about the practice is not only about demonstrating skills but also about visualising the aesthetics of the performance. Woermann (Citation2012, 628), who studied visual prosumption in the context of freeskiing, argues that social media ‘enhance the skiers’ abilities of retention, reflection and appreciation’. These three aspects are also realised in Jesse’s (32, runner) description of performance photography:

I make something out of shooting a photo. I think about the whole process as a kind of work of art … You perform and, during the performance, you get something out of it. And almost every time afterwards, you have a feeling of euphoria just because of the chemicals releasing into your body. But that you additionally document [the performance] into a beautiful package is a part of it.

By editing and ‘packaging’ performances, practitioners create products. In consuming these products, the audience, including the performer, has a secondary experience of the performance, attributes new meanings to it and, in turn, recreates the subculture (Snyder Citation2011; Woermann Citation2012). Instagram supports productisation by allowing users to add filters to modify the aesthetics of photographs and videos. However, users may prefer not to use them. For 33-year-old climber Mia, aesthetics cannot be created by using Instagram’s photograph-enhancing functions but must be found in the moment:

I don’t like to edit photos that I share on Instagram … Most often, I put them there pretty much raw. At the most, I balance the light somewhat. They [photographs] must look good in my eye already when I take them.

Aesthetic appreciation and delight of the physical practice frequently surfaced in the interviews as a theme that practitioners want to communicate through photo sharing. A 24-year-old climber, Julia, summarised:

I often write about current vibes. I like, for instance, this [shows a photograph on Instagram]. Here, I told people why I climb … I thought I could explain to everybody why this is great … There is something about our behaviour today – you want others to know, ‘Hey everyone, I’m having a good time!’

Furthermore, adding captions (including emojis) and hashtags to their photographs allows users to explain or specify what their photographs are about, convey different feelings, or categorise the content so that other users can find the photographs that are relevant to their interests. A content analysis of the captions and hashtags confirmed that through inspirational photographs, practitioners communicate feelings of appreciation (e.g. #nofilterneeded), joy (e.g. photo caption: ‘checking out the playground of the day’), happiness (e.g. #thehappynow), expectancy (e.g. #herewegoagain), and excitement (e.g. caption: ‘super excited to get to run some trails again’). Thus, practitioners use inspirational photographs to fulfil what Julia called the need ‘to share good vibes’.

Motivation

Apart from inspiration, climbers and trail runners engage in photo sharing on Instagram to motivate themselves and each other to undertake physical activity. In contrast to inspirational photographs that drive practitioners to explore, sharing motivational photographs encourages practitioners to keep going. Motivation is evoked through photographs that portray either overcoming challenges or togetherness.

Overcoming challenges

shows a typical example of the first motivational image type, ‘I did it’. In the photograph, a practitioner is sitting on a cliff and looking at a mountain on the horizon. The practitioner is flexing an arm to signal success. Other photographs in this category feature practitioners making different signs of victory, such as a V-sign hand gesture or upraised arms. Photographs presenting tangible proof of accomplishments, such as of a map with a marked route on it or of a display that quantifies a successful performance, also belong to this category.

In addition to posting photographs of athletic challenges, practitioners share photographs of challenges related to the conditions. shows a typical example of the second motivational image type, ‘no matter the weather’. It features a close-up photograph of a practitioner’s feet from above. On the left foot is a muddy sneaker, while the right foot is bare and equally dirty. The photograph conveys the idea that practice may not always be easy, but if a practitioner is passionate about it, they can perform regardless of the conditions or outcomes. Similarly, other photographs in this category feature rainy, muddy, or snowy conditions in which practitioners perform. The photographs are of practitioners, landscapes, or dirty equipment.

By sharing photographs of challenges and accomplishments, practitioners demonstrate the results of hard work and motivate each other to continue training despite challenges in order to reach practice-related goals. Matias (45, runner) explained that motivation acquired through visual communication is based on identification with other practitioners’ experiences:

When people post photos of their practice or if they have been running in beautiful landscapes, and when you support and enjoy someone else’s experience through likes and comments … These things strengthen communality and they’re important for keeping up my own motivation.

Instagram allows users to comment and ‘like’ other users’ posts with a heart-shaped symbol. The reciprocal feedback in the form of comments and likes generates appraisal support through which practitioners gather self-insight into their capabilities (see Langford et al. Citation1997). Research on social support on social media indicates that perceived social support is connected to the quantity and perceived quality of comments and likes that a user receives from others (Seo, Kim, and Yang Citation2016; Wohn, Carr, and Hayes Citation2016). By commenting on and liking each other’s posts, Instagram users confirm the focal ideas behind the photographs and accordingly collaborate in meaning making (see Schreiber Citation2017). Therefore, the value of an athletic accomplishment is validated by other practitioners’ reactions to the shared photograph.

Apart from appraisal support, sharing photographs of challenges and accomplishments rouse emotional support. Emotional support is manifested as expressions of sympathy and caring, and it is most commonly exchanged by strong social ties (Berkman et al. Citation2000). Anton (31, runner) elaborated:

When it comes to photos of people who are close to me, I’m interested in knowing that ‘ah, he had a good long run’. Those photos give me emphatic joy … the closer the person is to me the more, of course.

Isla (36, runner) explained how sharing photographs of less glamorous experiences stimulates emotional support. Her comment shows that the openness which practitioners highly value is not only related to open information sharing but also to honesty about the experience:

[Sharing photographs] is peer support with good and bad things … It’s more interesting to know that this person can also have a bad day. Somehow, it’s more supporting that ‘yeah (laughs), I don’t always have to be in top condition’. It’s somehow nicer.

The range of emotions that these ‘challenge’ photographs convey is also visible in the captions and hashtags. The analysis shows that through ‘challenge’ photographs, practitioners communicate feelings of amusement (e.g. caption: ‘Finnish spring surprises us again’), annoyance (e.g. caption: ‘we planned to climb this beauty today, but nature did not quite agree with the plan’), success (e.g. #irock), and contentment (e.g. caption: ‘what an educational journey’). Thus, practitioners use photographs to depict the ups and downs of physical practice. These photographs are highly motivational because, on one hand, they provide social support for practice and, on the other hand, they give examples of accomplished ambitions and, thus, encourage other practitioners to set their own goals for practice.

Togetherness

shows a typical example of the third motivational image type, ‘better together’. The photograph features a group self-portrait of four practitioners. One is in the foreground taking the photograph while the other three are standing closely behind holding each other. The photograph communicates that practice is more fun with others. Other photographs in this category feature groups of practitioners often with close intimacy and grinning faces. Similar to Hinch and Kono (Citation2018) analysis of ultrarunners’ photographs, the images in this category portray group energy.

By posting group photographs, practitioners both mediate their presence and demonstrate the solidarity that is present at a given moment. Jesse (32, runner) described how practitioners use photo sharing to communicate a heightened sense of communality in sports events:

Nowadays, people produce these kinds of event videos in which they are preparing themselves for something or they sit in a car on their way somewhere, like ‘yeah now we are having our last breakfast before the run’. … People do that to wrap up their experiences in events. I guess it’s a part of it.

Practitioners not only use group photographs to mediate current events but also to reconnect and recollect experiences of physical practice. Instagram allows users to tag or mention other users in the posts they share, which may further build communality among the people in the photographs. Mia (33, climber) explained how reliving shared experiences strengthens connections to others:

Often, when I share, there is someone else in the photo with me. Even when the photo is taken of me or a climbing wall, I share it with those – sure, with others too – but mainly with those who were there.

An analysis of the captions and hashtags confirms that practitioners communicate feelings of connection (e.g. #outdoorwomen) and gratitude (e.g. caption: ‘I want to thank you all for making it so wonderful’) through group photographs.

However, group photographs may not only be directed at those who were present in a given situation. Isla (36, runner) described how she uses them to encourage newcomers to join:

Yesterday, I shared a photo of our run. It was nothing special, but the weather was great. We had a good workout, the group was nice. I shared the joy … that we had a good group and a great time, that it felt easy. About togetherness (laughs), my main point about that post was that you should come along. I often share photos about joint practice. It brings people together.

Isla’s comment indicates that she readily welcomes new participants into the trail-running community. Further, other runners and climbers emphasised the culture of inclusivity. McCormack (Citation2017) finds a similar ethos in a study on subcultural identity formation among recreational mountain bikers. This contrasts with previous studies on lifestyle sports (e.g. Dupont Citation2014; Wheaton and Beal Citation2003), which highlight the exclusivity of subcultures.

Being open to new people echoes practitioners’ own need to belong – a need that is clearly manifested in runners’ and climbers’ photo-sharing practices. First of all, providing social support through visual communication makes practitioners feel needed. Secondly, by mediating their existence through photographs, practitioners assert themselves as part of the larger community of trail runners or climbers (see Olive Citation2015). Finally, by sharing the ‘better together’ photographs, practitioners can prove that they belong to the community and to the lifestyle sport subculture. This qualitative study, thus, resonates with Wong, Amon, and Keep’s (Citation2019) quantitative research showing that a desire to belong positively affects Instagram use and perceived social support from other users.

CONCLUSION

This study calls attention to the value of visual communication online in inspiring and motivating behaviour, in informing and affecting decision-making, and in constructing identities. In and through the process of photo sharing, the study participants exchange social support and build communality within their social networks.

The analysis has shown that climbers and trail runners use Instagram to tell visual stories about natural surroundings, athletic performance, togetherness, and overcoming challenges, and through these stories, they mediate their location and presence. In other words, they share photographs to communicate with and about the images while maintaining connections with others through phatic communication (see Lobinger Citation2016).

The study demonstrates that multiple types of photographs posted on Instagram have the potential to evoke feelings of connection and to reinforce a sense of communality. At first glance, only group photographs (‘better together’ image type) may seem important for solidarity. However, the study makes an important contribution by indicating that other types of ‘visually less communal’ photographs also strengthen communality, evidenced by the meanings that practitioners ascribe to the practice of sharing them. Therefore, we agree with McCormack’s (Citation2018) view that the practice of sharing visual stories online has the potential to strengthen social ties and create communality within subcultural social networks. Furthermore, we argue that this happens at its root because members of the networks consider the practice of sharing these stories meaningful in subculture-specific ways.

We conclude that visual communication on Instagram mediates a stream of momentary encounters between practitioners that merge into communally meaningful experiences. As such, photo sharing may provide alternative means to build connections with others in the era of networked individualism (Rainie and Wellman Citation2014). Online visual communication alone is not sufficient, however, to satisfy individuals’ need for a social life (Serafinelli Citation2017). In the context of recreational sport, face-to-face contact and shared physical experiences are also important for establishing emotionally meaningful social relationships (Ehrlén Citation2017).

That said, the value of online visual communication lies in its ability to maintain connection to other practitioners, not just through mediated presence (Villi and Stocchetti Citation2011) but through communal reflection on the values and meanings of physical activity, on the individual experiences of this activity, and on the natural surroundings in which such activity is performed. Therefore, we argue that in the context of recreational sport subcultures, visual communication is not only a facilitator of social relationships (cf. Serafinelli Citation2017) but can also be perceived as a meaningful social practice that is integral to the activity in question (see Woermann Citation2012).

As this study was limited to two sports disciplines, the results cannot be generalised to all sport-related or interest-based Instagram use. To draw more general conclusions about the role of visual media in communality building, more research is needed on the social networks that emerge around diverse leisure-time interests. Thus, this study should be seen as a signpost for future research on the potential of visual communication online in bringing people together and generating social support.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank our research participants for generously sharing their time and their stories with us. We also want to thank Juha Herkman and Janne Matikainen for their expertise and assistance in all aspects of this study and for commenting the manuscript. Finally, we thank the anonymous reviewers for their many suggestions for improving this paper.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Veera Ehrlén

Veera Ehrlén is a doctoral student in the Department of Language and Communication Studies at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research focuses on new media, digital culture, and network-based communication in the context of leisure-time activities. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9790-1865.

Mikko Villi

Mikko Villi is a professor in the Department of Language and Communication Studies at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. His work focuses on the contemporary context for distributing and sharing media content, especially on social media platforms. He has also gathered knowledge and expertise on themes related to new communication technology and forms of communication, in particular on visual and mobile media. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6935-9386.

Notes

[1] In this paper, the term ‘practitioners’ is used in reference to leisure physical activity enthusiasts, and particularly in reference to recreational climbers and trail runners.

[2] Nine of the 10 observed Instagram accounts were public. At the time of submission, all photographs included in the analysis were publicly accessible.

[3] The study participants used both Finnish and English in the captions and hashtags that they posted on Instagram.

[4] The extracts were translated from Finnish to English by the authors.

[5] To protect participants’ privacy, pseudonyms are used when presenting examples from the interview data.

REFERENCES

- Aslam, S. 2020. “Instagram by the Numbers: Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts.” Omnicore Agency (Blog). Accessed 10 February 2020. https://www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/

- Bale, J. 2003. Sports Geography. London: Routledge.

- Berkman, L., T. Glass, I. Brissette, and T. Seeman. 2000. “From Social Integration to Health: Durkheim in the New Millennium.” Social Science & Medicine 51 (6): 843–857. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4.

- Dupont, T. 2014. “From Core to Consumer.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 43 (5): 556–581. doi:10.1177/0891241613513033.

- Ehrlén, V. 2017. “Communication Practices and Social Tie Formation: A Case Study of Recreational Lifestyle Sports Cultures.” International Journal of Sport Communication 10 (3): 393–413. doi:10.1123/ijsc.2017-0032.

- Finn, J. 2014. “Amodern 3: Sport and Visual Culture.” Amodern 3.

- Getz, D., and A. McConnell. 2014. “Comparing Trail Runners and Mountain Bikers: Motivation, Involvement, Portfolios, and Event-tourist Careers.” Journal of Convention & Event Tourism 15 (1): 69–100. doi:10.1080/15470148.2013.834807.

- Gómez Cruz, E. 2016. “Photo-genic Assemblages: Photography as a Connective Interface.” In Digital Photography and Everyday Life: Empirical Studies on Material Visual Practices, edited by A. Lehmuskallio and E. G. Cruz, 228–242. London: Routledge.

- Gray, T., C. Norton, J. Breault-Hood, B. Christie, and N. Taylor. 2018. “Curating a Public Self: Exploring Social Media Images of Women in the Outdoors.” Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership 10 (2): 153–170. doi:10.18666/jorel-2018-v10-i2-8191.

- Grittmann, E. 2014. “Between Risk, Beauty and the Sublime: The Visualization of Climate Change in Media Coverage during Cop 15 in Copenhagen 2009.” In Image Politics of Climate Change: Visualizations, Imaginations, Documentations, edited by B. Schneider and T. Nocke, 127–151. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Grittmann, E., and I. Ammann. 2009. “Die Methode der quantitativen Bildtypenanalyse: Zur Routinisierung der Bildberichterstattung am Beispiel von 9/11 in der journalistischen Erinnerungskultur.” In Visuelle Stereotype, edited by T. Petersen and C. Schwender, 141–158. Köln: Halem.

- Hinch, T., and S. Kono. 2018. “Ultramarathon Runners’ Attachment to Place: An Interpretation of Runner Generated Images during On-site Training Camps.” Journal of Sport & Tourism 22 (2): 109–130. doi:10.1080/14775085.2017.1371065.

- Langford, C., P. Hinson, J. Bowsher, J. Maloney, and P. Lillis. 1997. “Social Support: A Conceptual Analysis.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 25 (1): 95–100. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x.

- Lapenta, F. 2011. “Geomedia: On Location-based Media, the Changing Status of Collective Image Production and the Emergence of Social Navigation Systems.” Visual Studies 26 (1): 14–24. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2011.548485.

- Lobinger, K. 2016. “Photographs as Things – Photographs of Things: A Texto-material Perspective on Photo-sharing Practices.” Information, Communication & Society 19 (4): 475–488. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2015.1077262.

- Lomborg, S. 2015. ““Meaning” in Social Media.” Social Media + Society 1 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1177/2056305115578673.

- McCormack, K. 2017. “Inclusion and Identity in the Mountain Biking Community: Can Subcultural Identity and Inclusivity Coexist?” Sociology of Sport Journal 34 (4): 344–353. doi:10.1123/ssj.2016-0160.

- McCormack, K. 2018. “Building Community Online and on the Trail: Communication, Coordination, and Trust among Mountain Bikers.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (4): 564–577. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2017.1290128.

- Olive, R. 2015. “Reframing Surfing: Physical Culture in Online Spaces.” Media International Australia 155 (1): 99–107. doi:10.1177/1329878x1515500112.

- Panofsky, E. 1972. Studies in Iconology. Humanistic themes in the art of the renaissance. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Prieto Blanco, P. 2016. “Digital) Photography, Experience and Space in Transnational Families. A Case Study of Spanish-Irish Families Living in Ireland.” In Digital Photography and Everyday Life: Empirical Studies on Material Visual Practices, edited by A. Lehmuskallio and E. G. Cruz, 122–141. London: Routledge.

- Rainie, L., and B. Wellman. 2014. Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Rickly-Boyd, J. 2012. “On Lifestyle Climbers: An Examination of Rock Climbing Dedication, Community, and Travel.” PhD diss., Indiana University.

- Rose, G. 2014. “On the Relation between ‘Visual Research Methods’ and Contemporary Visual Culture.” The Sociological Review 62 (1): 24–46. doi:10.1111/1467-954x.12109.

- Schreiber, M. 2017. “Showing/sharing: Analysing Visual Communication from a Praxeological Perspective.” Media and Communication 5 (4): 37–50. doi:10.17645/mac.v5i4.1075.

- Schreier, M. 2014. “Qualitative Content Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, edited by U. Flick, 170–183. London: SAGE Publications .

- Seo, M., J. Kim, and H. Yang. 2016. “Frequent Interaction and Fast Feedback Predict Perceived Social Support: Using Crawled and Self-reported Data of Facebook Users.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 21 (4): 282–297. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12160.

- Serafinelli, E. 2017. “Analysis of Photo Sharing and Visual Social Relationships: Instagram as a Case Study.” Photographies 10 (1): 91–111. doi:10.1080/17540763.2016.1258657.

- Serafinelli, E., and A. Cox. 2019. “‘Privacy Does Not Interest Me’. A Comparative Analysis of Photo Sharing on Instagram and Blipfoto.” Visual Studies 34 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1080/1472586x.2019.1621194.

- Serafinelli, E., and M. Villi. 2017. “Mobile Mediated Visualities an Empirical Study of Visual Practices on Instagram.” Digital Culture & Society 3 (2): 165–182. doi:10.14361/dcs-2017-0210.

- Snyder, G. 2011. “The City and the Subculture Career: Professional Street Skateboarding in LA.” Ethnography 13 (3): 306–329. doi:10.1177/1466138111413501.

- Systrom, K. 2018. “Welcome to IGTV.” Instagram (blog). Accessed 20 June 2018. https://instagram-press.com/blog/2018/06/20/welcome-to-igtv/

- Thorpe, H. 2017. “Action Sports, Social Media, and New Technologies: Towards a Research Agenda.” Communication & Sport 5 (5): 554–578. doi:10.1177/2167479516638125.

- van Bottenburg, M., and L. Salome. 2010. “The Indoorisation of Outdoor Sports: An Exploration of the Rise of Lifestyle Sports in Artificial Settings.” Leisure Studies 29 (2): 143–160. doi:10.1080/02614360903261479.

- van Dijck, J. 2013. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Villi, M. 2010. Visual Mobile Communication: Camera Phone Photo Messages as Ritual Communication and Mediated Presence. Helsinki: Aalto University School of Art and Design.

- Villi, M. 2012. “Visual Chitchat: The Use of Camera Phones in Visual Interpersonal Communication.” Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture 3 (1): 39–54. doi:10.1386/iscc.3.1.39_1.

- Villi, M. 2016. “Photographs of Place in Phonespace: Camera Phones as a Location-aware Mobile Technology.” In Digital Photography and Everyday Life: Empirical Studies on Material Visual Practices, edited by A. Lehmuskallio and E. G. Cruz, 107–121. London: Routledge.

- Villi, M., and M. Stocchetti. 2011. “Visual Mobile Communication, Mediated Presence and the Politics of Space.” Visual Studies 26 (2): 102–112. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2011.571885.

- Wheaton, B. 2010. “Introducing the Consumption and Representation of Lifestyle Sports.” Sport in Society 13 (7–8): 1057–1081. doi:10.1080/17430431003779965.

- Wheaton, B., and B. Beal. 2003. “‘Keeping It Real’: Subcultural Media and the Discourses of Authenticity in Alternative Sport.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 38 (2): 155–176. doi:10.1177/1012690203038002002.

- Woermann, N. 2012. “On the Slope Is on the Screen: Prosumption, Social Media Practices, and Scopic Systems in the Freeskiing Subculture.” American Behavioral Scientist 56 (4): 618–640. doi:10.1177/0002764211429363.

- Wohn, D., C. Carr, and R. Hayes. 2016. “How Affective Is a “Like”?: The Effect of Paralinguistic Digital Affordances on Perceived Social Support.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 19 (9): 562–566. doi:10.1089/cyber.2016.0162.

- Wong, D., K. Amon, and M. Keep. 2019. “Desire to Belong Affects Instagram Behavior and Perceived Social Support.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 22 (7): 465–471. doi:10.1089/cyber.2018.0533.