Abstract

This article examines the usefulness of participant-produced drawings as a participatory and non-mechanical visual research methodology in qualitative research with UK-based African Diaspora communities. Because of its co-construction and mediation of situated knowledgies, adaptability and with linguistic proficiency a non-prerequisite skill for drawing literacy; participatory drawings are considered particularly productive and ethically sound for work with children, young people and in the case of this research, adults, in different social and cultural contexts. Thematic and critical discourse analyses of drawings, supplemented by textual/written information and subsequent discussions about these visual productions, have the powerful potential to unearth complex (and seemingly hidden) subtleties of thought, memories, sentiments and information for (and by) participants, in ways that are illustrative, self-empowering, and individualised. As a review of drawing methodology, as a visual qualitative research method, the author discusses its usefulness and limitations, using his work with African Diaspora communities for/as context.

INTRODUCTION

The critical knowledge production and theoretical developments derived from written and verbalised/auditory epistemologies of ‘knowing about’ and of ‘seeing’, have seemingly conceived such methods as ‘always-already’ prioritised as the methodological ‘go-to’ within the broad and often transdisciplinary areas of communication studies. Nonetheless, an alternative and contemporary offering of non-textualised methodologies have emerged as the new darling, preoccupying the seemingly bound-ary-less epistemological frontiers of qualitative research inquiry. Specifically, arts-based and participatory visual communications, such as photography, film, digitalised graphics and drawings – the latter of which this article is necessarily concerned. These qualitative strategies are imbued with a transformational potential to illustrate the nuanced complexities and idiosyncratic features of human subjectivities, whilst simultaneously empowering individual participants by re-orientating the locus of control, agency and authorship of lived narratives literally at their fingertips. By way of visual imagination, attendant written information, and subsequent reflective discussion of participant-authored visual material in the context of their production, participants are afforded a creative space and opportunity to articulate (and appropriate meaning from) their introspective worldviews. As well as being credited as active, empowered and meaningful contributors of the research process and outcome. So too, because of its self-directed accessibility, adaptable nature and its non-prostration to linguistic proficiency, this research method is palatable and complementary to qualitative studies with all types of people across a variety of intellectual abilities, backgrounds, and cultural contexts.

Solidly anchored within the broader transdisciplinary axes of qualitative visual research in the Social Sciences, this article provides a methodological and reflective commentary on the use(fulness) of participant-produced drawings as a participatory and non-mechanical visual mode of knowledge production in qualitative research. Drawing from critical discussions within the core literature on this subject, and from my own research using this method with Black British communities of African heritage, this article is primarily concerned with furthering knowledge on the practice of drawing as a distinctively qualitative methodological approach for research purposes. Within this framing, it will provide (and be) a methodological review of a somewhat understudied and underappreciated method of inquiry within the milieu of qualitative research. First, it will set the scene with a background context of the Social Science deployment of visual methodologies. Followed by a critical discussion of the comparative affordances of visual communications juxtaposed against textual (non-visual) forms of communicative enquiry within the realm of qualitative research. Lastly, the article evaluates both the practical and ethical strengths of drawing methodology and attendant limitations for the qualitative researcher.

THE SOCIAL SCIENCES AND VISUAL RESEARCH METHODOLOGIES: a HISTORICISED PICTURE

Any suggestion that the deployment of visual research methodologies in the contemporary Social Sciences is a relatively new phenomenon is simply misinformed. However, what is indeed ‘new’ is the progressively participatory approaches through which these modes are practiced. In the context of strategies used, the methodological inventory file cabinet is, according to Prosser (Citation2007), comprised of both mechanical tools (e.g. video and photography) and non-mechanical ones (e.g., drawing, collage, Lego, playdough, games-making and similar others). Similarly, within the context of contemporary participatory research methodologies, this methodological polarity is best defined by and contextualised as, an epistemological and practical separation between computer-generated (digitalised) and non-computer-generated (non-digitalised) strategies. Some, including Mitchell, Walsh, and Moletsane (Citation2006) in their study of vulnerability among sexually abused children, have opted to combine both approaches based on their comparative complementarities.

Visual methodologies such as, ethnographic photography and documentary film were primarily used within the Social Science sub-field of visual anthropology as a form of visual documentation of, and supplementary material for, their textual narratives about indigenous civilisations (See., Collier and Collier Citation1986; Scherer Citation1992; MacDougall Citation2001; Marett Citation2005). Nonetheless, these historicised anthropological practices are situated antithetically to the philosophies which undergird participatory processes, as they necessarily (re)orientated human participants under the subjugating and hierarchically racialised lens of colonialism. Apart from the anthropological and sociological field, visual research methods and particularly, the use of drawing techniques, have been deployed in various forms within psychology. As advised by MacGregor, Currie, and Wetton (Citation1998); as early as 1935, psychologists, psychiatrists, psychotherapists and social scientists have worked with children and adults using a multiplicity of ‘draw-and-write’, ‘draw-and-talk’ and more recently the three-pronged ‘draw-write-and-talk’ techniques that have allowed for a rich tapestry of participant-curated knowledgies derived from children and adult intimate world reflections, perceptual interpretations, imaginings and opinions on varied subjects and phenomena (MacGregor, Currie, and Wetton Citation1998; Backett-Milburn and McKie Citation1999; Furth Citation2002; Guillemin Citation2004; Mair and Kierans Citation2007).

Inflamed by the intellectual assumptions of post structuralism, the arrival of participatory communication theory and practice(s) of the 1970’s provoked an epistemological and attitudinal shift away from the unequivocal ‘indignity of speaking for others’ (Foucault Citation1977, 209) and towards centring the means and locus of visual production (be that a colouring pencil, disposable camera, or a digital camcorder) into the competent hands of the participant authors themselves. The materialisms of such thought are largely demonstrated within the fields of international development studies, community learning and development, as well as, international Social Work, mainly because of their cross-cultural adaptability and transformational potential to engender individualised and collective empowerment. In these disciplinary spaces, educational technology research via participatory video, audio and video elicitation and arts-based programmes (to name a few) as part of action research projects, has been influential in popularising the application of this methodology for monitoring and impact evaluation (Jupp-Kina Citation2015; Literat Citation2013; Singhal et al. Citation2007).

These approaches, while used with both children and adults in different social, cultural and national contexts, have largely privileged the marginalised voices and contributions (of often unrecognised) impoverished communities situated in the global South. This is particularly, true for studies commissioned by international development and humanitarian NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations). Especially given recent efforts at addressing institutional, academic and public criticism of unethical representational practices, by affording predominantly African, Asian and Middle Eastern children (many of whom are refugees, and from other disenfranchised groups), opportunities to become active stakeholders in photographic and filmic content concerning portrayals of their identities and lived-realities in western charity appeals. (Girling Citation2017; Warrington and Crombie Citation2017; Ademolu and Warrington Citation2019; Ademolu Citation2019).

The literature on visual methodologies with adult populations, especially in the UK context, while available, is comparatively understudied and less diverse set against children and youth. Let alone the availability of targeted qualitative studies which have exclusively sought (and privileged) the subjectivities and introspections of African Diaspora – that is, British adult communities of Black African heritage. This, even with fine combing, is difficult to retrieve. As such, these communities are yet to be comprehensively studied in the full context of visual methodologies nor seen as an interesting and meaningful ‘subject’ of analysis. This unfortunate reality is further complicated by the fact that Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) communities are grossly underrepresented in research, for a variety of reasons, including linguistic barriers, cultural and religious considerations, (in)accessibility, misunderstandings of research participation and general(ised) mistrust and suspicion of the researcher-participant process (Ellard-Gray et al. Citation2015; Gubrium and Harper Citation2013). The latter point of which is deeply historicised in problematisations and explanations of racism, racial tokenism and attendant forms of discrimination, insensitivity and mistreatment.

With that said, the largely child-and-youth-favoured literature, from which we can draw on, demonstrate that there are numerous important instrumentalisations that have made meaningful theoretical and practical contributions to this progressive field. One notable contribution in this area is the pioneering application of the ‘dialogical pedagogy’ approach developed by Brazilian educationalist and philosopher Paulo Freire, which espouses, centralises and problematises notions and practices of egalitarianism, anti-oppression, interaction and transformation in learning processes between individuals, communities and institutions (Freire Citation1970). While undertaking literacy-based research in a slum dwelling neighbourhood of Lima, Peru in 1973, Freire (accompanied by his co-researchers) asked the Spanish-speaking communities therein, to answer the question of ‘What is exploitation?’ Rather than simply eliciting their verbalised narratives, he requested they document their responses via means of photography. With cameras in tow, some community members captured pictures of authoritative figures, such as landlords and policemen.

Bucking this trend, however, one child participant photographed a nail on the wall. This conceptual and seemingly incomprehensible visual documentation of exploitation was largely lost on the adult facilitators, but readily understood by the fellow Peruvian child photographers. Subsequent discussions about the meaning of and motivations behind the child’s picture explicated this. A disproportionate number of the young boys in that neighbourhood worked in the shoe-shining industry, while their clients were city-residents, who lived a fair distance away from the slums of Lima. With the weighty cumbersome shoe-shine boxes being difficult to carry on their daily commute to the city, these boys resorted to renting a hammered nail on a wall, often within a shop, to hang their boxes overnight. As such, from their own individualised and community perspective, this seemingly inconsequential metal fastening used to ease their physical burden, was in fact, a significant symbolism of (their) institutional exploitation (Singhal and Rattine-Flaherty Citation2006).

The broad contemporary field of qualitative visual research methodologies has disproportionately favoured digitalised developments in photographic and video tools over, what now seems to be, the old ‘tradition’ of drawing (Wang Citation2007). As such, photovoice and digital storytelling have ushered a new ‘way of thinking’ – a reconceptualisation – and practical ‘know how’ among qualitative practitioners working with children and young people. While participant-produced drawings have been used in child-centred qualitative inquiries, this is to a much lesser extent, with much credit afforded to renowned educationalist Noreen Wetton, who since the 1980s, has spearheaded this strategy for understanding how primary school-aged children negotiate and articulate interpretations of their situated knowledgies, primarily in the context of health education (Wetton and McWhirter Citation1998; Williams, Wetton, and Moon Citation1989). Campbell et al. (Citation2010) deployed participatory drawings (supplemented with written stories) in a study with 50 aids-affected Zimbabwean children aged 10–12, to explore their experiences (as well as, resistances and reframing) of community stigmatisation. While in the UK context, McNicol (Citation2019), adopted participant-produced comics as a research method with British Bangladeshi women living in Greater Manchester.

Despite this repository of critical literature, empirical examples of drawing in qualitative visual communication studies with (and concerning), the marginalised perspectives of Black British adults of African heritage is incredibly limited. Where there are examples of work with Black racialised communities, empirical preoccupations are invariantly orientated towards ‘knowing’ the subjectivities of continental Africans in the global South and not that of their British-situated and acclimatised diaspora counterparts. This is not to say that studies have not involved diaspora communities or have seemingly monocultural and homogenous participant groups. However, what is certain is that this literature is hard to pinpoint among the horde, given that no explicit attention has been paid solely on privileging the empirical and thematic realities of African diaspora participants. The review of current visual methodology literature also demonstrates a disproportionate leaning towards documentations of participant-centred photography and video outputs and evaluations. With less attention afforded to non-mechanical and participatory forms of drawing ‘as qualitative research’ that is worthy of continued empirical contemplation and use.

SITUATING THE VISUAL AGAINST THE TEXTUAL: a COMPARATIVE FRAMING

Drawing as a visual mode of qualitative empirical expression in the Social Sciences is a multidimensional and complex practice that is at its most pronounced and productive within contexts that provide the critical space and opportunity for this strategy to actively appropriate the affordances imbued in this visual medium. As Weber (Citation2008) advises, ‘Images can be used to capture the ineffable. Some things just need to be shown, not merely stated. Artistic images can help us access those exclusive hard-to-put-into-words aspects of knowledge that might otherwise remain hidden or ignored’. While, Kress (Citation2004, 111), in his summary of the fundamental usefulness of visual and textual modes, suggested that the latter is ‘the (transformed) recollection of the actionally experienced world through the temporally organised mode’. Using a social semiotic lens to contextualise the value of visualised methodologies, he expounds on how pictorial representations are imbued with a certain spatial and temporal quality that allows them to express dimensions of space and time in ways that are bound-ary-less and unencumbered (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2002). Within the framing of spatial representation, drawings can illustrate interconnections (and disconnections) between visual components in ways that are somewhat incomprehensible and challenging via the ‘logical’ constraints of textual and/or auditory forms of expression. In terms of time, textual representations – writing and speech – are necessarily circumscribed by the narrow limitations of ‘the “logic” of temporal sequence’ (Kress Citation2004, 112). Contrastingly, visual representations essentially defy organisational linearity, allowing for a more comprehensive, integrated illustration of theoretical ‘meaning-making’, ideas, emotions and information without prostrating to a demand for certain elements to be prioritised along a temporal sequence.

The transformational potential wielded in visual representations like drawings, is demonstrated in their ability to construct metaphorical expressions and consciousness of human individualities, conceptual ideas and situated knowledgies. As such, they allow for the emergence of (often spontaneously occurring) abstract and imaginative thought. By themselves, images – and drawing ‘as practice’ – are thought of as metaphors for complex subjectivities of human and social phenomena. While their textual counterpart is equally conceived as a metaphor, they demand a certain level of intellectual and linguistic proficiency not always-already possessed and demonstrated by all people (especially young children) nor is it reflective of their neurodiversity. Indisputably, image-production are visually externalised metaphors of conceptual interiorities of lived-realities. Substantially, images ‘as content’ is relatively more productive than digitalised and mechanical modes of visualisation such as, camcorders, given that participants must physically and imaginatively engage in acts of materialising, through drawing, their social world. As opposed to simply ‘pick and mixing’, ‘sift and sorting’ through and curating select particularities of the external environment, to document in videographic form or a photograph, in the case of a camera (Banks Citation2001; Gauntlett Citation2007).

Another methodological consideration that makes drawing methodologies ideal in qualitative research is the fact that it allows participants the flexibility in terms of time to (re)conceptualise and reflect on their responses, encouraging a more rounded and considered representation of their thoughts. This in contrast to the often time-conscious linguistic traditions of interviewing and focus group discussions, which methodologically, do not necessarily permit as much time and opportunity for measured and reflective introspection (Gauntlett Citation2007).

Equally important, Rattine-Flaherty and Singhal (Citation2007) contend that this non-mechanical visual strategy, when compared to traditional written and oral research methods, is largely considered more nuanced and sophisticated. This is because it has the methodological potential to summon seemingly dormant, semi-conscious and unrealised memories, sentiments and perspectives. As such, analyses of pictorial modes of visual representation may (and often does) reveal more subtle, seemingly inconsequential messages and vague realities than non-visual, text-based research techniques. Similarly, by granting imaginative space, freedom and opportunities for participants to exercise self-determined authorship over the content and framing of their own productions, these methodologies can reveal interrelationships between what is ‘seen’ and ‘unseen’. Thus, significance is found in both the observable and imperceptible and the nuanced spaces between. It is this latter point – drawing methodologies’ signification of the seen and unseen – that makes its readily accepting of and complementary to the interpretative practices of discourse analysis applications, which can help to connect, implicate, historicise and problematise the content and context of drawings. As well as, participant’s interpretations of these visual representations into broader, macro-level, structural discourses, (power)relationships, processes and systems (Wodak and Meyer Citation2009). This is something that I found productive and illuminating in my application of a postcolonial discourse analysis framework when interpreting the discursive complexities of participant-produced drawings (and supplementary text and oral discussions). Using examples, this will be expanded on in the ensuing section on the ethical and practical use(fulness) of drawing methodologies.

DRAWINGS AS METHODOLOGICALLY ETHICAL AND PRACTICAL

A principal benefit of incorporating drawing methodologies (either as a standalone or in combination with additional methodologies) in Social Science qualitative research is that their participatory features means that they are more inclusive, situationally flexible and interactional. With research practitioners paying increasing attention to the social-cultural framing, hierarchical structures, relationships, positionalities and processes concerned with (and which affect and constitute) the production of empirical information. This necessarily demands an understanding of how research participants themselves (especially vulnerable individuals, groups and communities such as, children and racialised minorities), define and comprehend (expectations of) the research task and process(es). So too, how their modes of expression are almost-always informed by the setting and method of knowledge production (Backett-Milburn and McKie Citation1999). Within this framing, and much in the spirit of Freire’s dialogic pedagogy, this visual approach to qualitative inquiry is advantageous as it dissuades and problematises asymmetrical researcher-participant relationships. This sensitivity to and epistemological consciousness of needing to be more horizontal than vertical, make such techniques comparatively more ethically cognisant than their textual counterparts. In this sense, drawing is widely understood to be fundamentally interpretivist in epistemological principle and approach (Papert and Harel Citation1991). However, this is not to underestimate the material implications and significance of certain influential aspects of researcher-participant positionality (e.g., age, gender, race, social-economic status, sexual orientation, professional background, etc.), on the research process, dynamic, outcome and analysis of drawing.

When set against its more contemporary-digitised varieties like photovoice and digital storytelling, the traditional mechanisms of drawing, a technologically independent, low-skilled artisanal mode, we see how it affords (some degree of) equivalency between the participant and researcher. Thus, the hierarchical, authoritative knowledge and technical ‘know how’ that ineluctably accompanies, and which constitutes, participatory forms of photography and video activities, are virtually not applicable in the context of drawing. Where participants are comfortable in (and with) the profound interiority of a familiar activity, while the researcher, is arguably, looking from the outside in (Druin et al. Citation1999).

Similarly, given drawing’s encouragement of co-construction this provides an expressive and accommodating frame and space within which participants meaningfully exercise self-determination when manoeuvring the artistic direction of their own realities. This practice thus has the transformational potential to facilitate and/or reinforce one’s internal locus of control, that is the degree to which someone psychologically attributes (and feels like they have) control, management, self-governance and authorship over the narration of their lived-realities. As opposed to, an external locus of control where attribution is located within external considerations, beyond the hands and control of the individual self (Bandura Citation2001). The practice of drawing, in a participatory context, empowers and psychologically nourishes the child-and-adult-drawer with self-efficacy.

Among the progressively expanding and imaginative repertoire of qualitative research methodologies, drawing is a comparatively more artistically accommodating, participatory and indiscriminately inclusive activity. These fundamental features can potentially reconfigure the ordinariness and straightforward-ness of the research project and process into something that is novel, fun and readily accessible for all involved. So too, it can help maintain and re-focus sometimes depleting levels of enthusiasm and attention, especially among young participants where uninterrupted concentration is a challenge.

Interestingly, in the context of my own research, there was some initial apprehension on my part, compounded by preoccupations that my adult participants who ranged from ages 19–58 years old, would find drawing a rather uninspiring, inconsequential, age-inappropriate, inconvenient, or worst still, a patronising activity. Especially for the young, twenty-something-year-old millennial, London ‘urbanites’, who may have considered drawing antiquated and ‘uncool’. So too, I rationalised that some participants might have certain frustrations towards a seemingly unsophisticated mode of knowledge production, compared to the all-too-familiar interview.

Despite these understandable trepidations, the drawing medium seemed to be an intuitively entertaining, care-free and meditative experience for all adult research participants, who with graphite and colouring pencils, felt-tip and/or the humble ballpoint, between fingers and thumb, produced unapologetic artistic articulations of their own immediate and external environments as they ‘know’, ‘see’ and experience(d) it.

Additionally, an important usefulness of drawing methodologies is their incredible malleability and adaptability to different learning-research situations. As aforementioned, participatory forms of drawing – unlike (or to a lesser extent than) other mechanical visual modes such as, video and photography – can be implemented and practiced in (and across) different social, cultural and linguistic conditions. This is particularly pronounced it international/cross-cultural contexts, where linguistic barriers to communication seem to pose as a tricky, impenetrable terrain to negotiate common ground of mutual understanding.

Finally, the relative flexibility of drawing is demonstrated in its potential to be instrumentalised at different (and non-sequential) stages of the qualitative research process: the data collection and interpretation/analysis stages, for example. This adaptability is incredibly rewarding for the researcher and participants in the often-iterative process of qualitative knowledge production. Especially, as this helps facilitate a more enriched, consolidated and comprehensive assessment process, while affording opportunities to consult and administer supplementary research methods/methodologies. The following examples, from my own research with first- and second-generation African diaspora communities living in London and Manchester, UK, will illuminate this adaptability and responsiveness to supplementary qualitative methodologies. It does this by demonstrating the use of the participatory drawing method as both an introductory exercise at the formative research stage, to elicit superficial-level ‘prima facie’ understandings of participant subjectivities through a cursory review of drawings. As well as empirical material for sophisticated theoretical interpretation via a postcolonial critical discourse analysis (CDA) approach. Supplemented with semi-structured focus group discussions, for a more comprehensive evaluation.

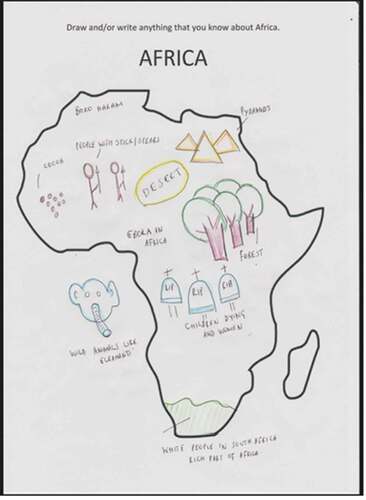

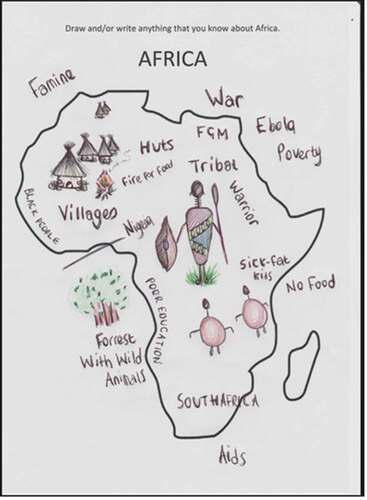

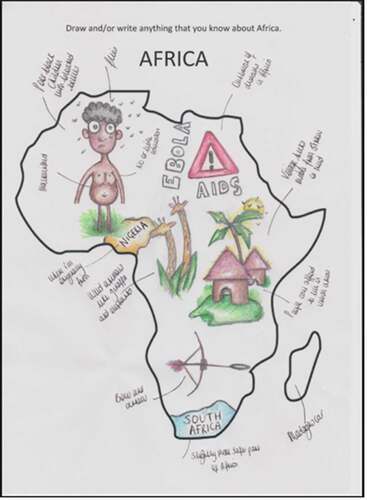

This illustration above was part of an introductory exercise called ‘Africa Map Drawing’ at the formative research stage. Which attempted, through the medium of drawing, to address the broader research question of the role (or lack thereof) that international development and humanitarian representations of Africa(ns) in NGO fundraising advertisements, have for the different ways that identifying Black British communities of African background, ‘think’ and ‘know about’ their continent and/or country of heritage. Inspired by the drawing and writing methodologies used in the Leeds University Centre for African Studies (LUCAS) ‘African Voices’ school project,Footnote1 a series of activity workshops delivered by African postgraduate students in local primary schools, to assess and challenge (9–11-year-old) children’s (pre-existing) perceptions and knowledge about continental Africa and communities therein. In the context of my own work, ‘Africa Map Drawing’ activities were used specifically to assess adult diaspora participants’ prior knowledge and perceptions in response to the question: ‘When you think of Africa, and/or your country of heritage, what comes to mind?’

, a drawing (and accompanying text) by 32-year-old Lola, portrays an almost children’s book-like illustration, better yet a satirical cartooning, of colourful imaginings of some typical ‘African paraphernalia’ that abound charity appeals: fly-infested, malnourished (seemingly) parentless child, with an expressionless yet imploring gaze, distended-abdomen and obligatory nakedness, with field-mounted straw/mud huts. This is accompanied by a bright red triangular hazard road sign, with exclamation mark in-tow, alerting one’s attention to ‘Ebola’ and ‘Aids’ therein, emphasised by the narration: ‘outbreak of diseases in Africa’; giraffes in the wild and a singular bow and arrow. Lastly, we see three identified regions of Africa: 'Nigeria', Lola’s country of heritage, labelled with the text ‘Where I’m originally from’; 'South Africa' with the attendant designation: ‘Slightly more safer part of Africa’ and a label pinpointing 'Madagascar'.

FIGURE 1. Lola – ‘Africa Map Drawing’ in response to the question: ‘When you think of Africa and/or your country of heritage, what comes to mind?’.

Within this visual frame, we see, on a cursory level analysis of Lola’s drawing, the showcasing of several of the modal affordances of this non-mechanical methodology, as aforementioned. This participant’s utilisation of the visual space to articulate a rather simple yet (oxymoronically) sophisticated, skilled, contemplative and whimsical detailing of her perceptual interpretation of Africa(ns) would have been unattainable, and if not, less pronounced with textual methods and/or oral interviewing. However, communicated in the visual form of drawing, it reveals a powerful ‘knowing’ that is deeply personal and seemingly informed in one way or another, by the subconscious osmosis of African imageries circulated by and negotiated through media apparatuses like NGOs, as visual African knowledge producers. Indeed, one of the first things that Lola did was draw a picture of a lone Black child at the very top-left protuberant part of the silhouetted African continent, disproportionally-large relative to other illustrations (but adjacent to ‘Ebola’ and ‘Aids’) and certainly towering over the other elements of her drawing. As if alluding to some hierarchical arrangement of perceptual significance of/for Africa. This provides an insightful glimpse into the metaphorical symbolisms she has for her continent/country of heritage that may reflect memories, conceptualisations, infiltrated knowledgies, assumptions, etc., that are both latent and salient at the frontiers of her mind’s eye.

It is also interesting to note the attention she affords to the rather uncommunicative, wearied and googly-eyed child not just in terms of their occupied space and positioning on the page, but also that this child is the only human representative present in the drawing. This is meaningful, not least that it says something about Lola’s metaphorical interpretation of Africa as (and through) ‘child’ or perhaps the disposition of communities therein. This is something that we will revisit in the ensuing discussion about how drawing is perfectly suited to theoretical/discourse analysis.

What’s particularly illuminating is Lola’s (almost intuitive) recourse to common visual tropes of death, disease, poverty, wildlife, etc., in Africa (as shown through the ‘African paraphernalia’); tropes which always-already frame the continent (and its people) within ineluctable and problematic interpretations of negative, social, cultural and geographical stereotypes. This is highly meaningful, not least that it speaks volumes, about how she imagines and construes continental Africa, in ways that may appear almost common-sensical or self-evident at least from her own individual perspective. Indeed, this visual normative assumption of Africa(ns) within this particular frame was discernible, in one fashion or another, in other diaspora participant drawings. Taken for instance, below, produced by 19-year-old student Ezekiel, while simplistic in its presentation it is nonetheless an equally illuminating drawing which showcases similar interpretations, visual tropes and allusions to a particular type of Africa. This is substantiated by a depiction of three cemetery tombstones inscribed with ‘RIP’ (acronym for Rest in Peace) accompanied by text which reads ‘children and women dying’. Additionally, we see a picture of an elephant with the words ‘wild animals like elephants’ as well as, the words ‘Ebola in Africa’.

When contextualised using a postcolonial CDA, these drawings allow for, and are receptive to, more sophisticated levels of analytical interpretation, that moves beyond the superficiality of ‘first review’ or ‘at first glance’ cursory impressions, and towards an understanding that implicates, historicises and frames these visual modes of participant ‘sense-making’ within broader theoretical discourses. Before detailing some of my analytical findings, it is important, for sake of clarity, to first explain what CDA is and the specific postcolonial approach I used. CDA is a transdisciplinary approach – or a constellation of approaches – to the analysis of non-linguistic and linguistic text that is unified, not so much by a shared theoretical or methodological framework, but by a collective ambition of not just merely describing but also explaining and critically evaluating the significance of text (written, visual and otherwise) in producing, maintaining, and legitimising social inequality, injustice, and oppression (Van Leeuwen Citation2007). The postcolonial slant of CDA, which my research adopted, contextualises the overall objective of CDA within an analytical focus on, and foregrounding of, the subjectivities and lived realities of indigenous, and marginalised (formally)colonised communities (of and) from the global South, such as Black racialised African diaspora groups. It does this to understand, examine, critique, problematise and challenge hierarchical and asymmetrical systems of power that pervaded the relationship between colonial powers and colonised areas (and people therein).

Specifically, my work draws from the postcolonial concept ‘Imaginative Geographies’ originally formulated by influential postcolonial critic Edward Said. Imaginative geographies are representations – ‘ways of seeing’ and ‘knowing about’ – the so called, ‘Other’ (e.g., faraway, foreign, non-white, non-western, etc.) places, people and landscapes and how these imaginings reflect the preconceptions, fantasies, projections and preoccupations of their authors, who are generally external observers (Said Citation[1978]2003). The dramatisation, reproduction and reification of perceived distance and dissimilarity between the ‘Self’ and ‘Other’, or between ‘home’ and ‘abroad’, is a necessary part, and unit of analysis of imaginative geographies. This is demonstrated through, in the context of my own work, visual modalities and inferences of ‘difference’.

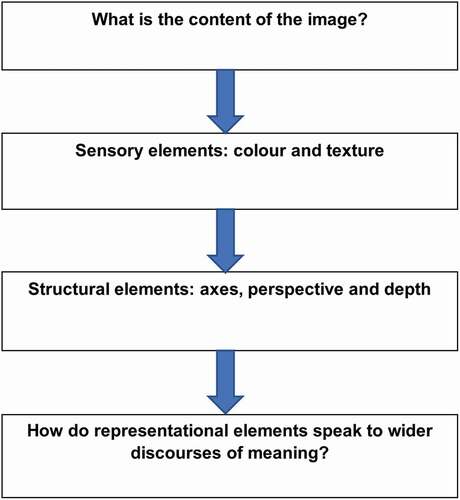

In terms of how drawings were analysed and discursive reflections made. I used a four-stage model of visual analysis (see ) adapted from the works of Campbell et al. (Citation2010) who used Social Representations Theory (STR) as a conceptual lens to analyse how Zimbabwean children represent AIDS-affected peers through drawings and accompanying stories. Additionally, Hook & Glaveanu’s (Citation2013) interactive approach to the analysis of compositional elements of still visuals was utilised, who suggest a classification of compositional elements and identify ways in which such elements can be analysed and interpreted. Casting light on the range of rhetorical and ideological effects that images so often achieve.

Drawings and accompanying interview narratives were analysed as a single unit. Each drawing was analysed using the four-stage framework which started by exploring its content, followed by sensory elements (colour, lighting and texture) and then, structural elements (axes, perspective and depth). The final stage involved classifying any account that threw light on the ideological modalities and discourses of my ‘Imaginative Geographies’ conceptual framing. This latter stage involved isolating specific elements that were particularly salient and evocative and discussing with participants how they relate to wider structures of meaning according to their own imaginative interpretations of ‘home’.

Guiding ‘issues of interest’ (Campbell et al. Citation2010) were looked for as I analysed the drawings. When exploring the ‘content’ of drawings in stage one, for example, I paid particular attention to ‘Who’ and ‘What’ was included/excluded from drawings: the identities of people and characters, gender, activities occurring and settings. While for sensory elements, interest was in the dominant or ‘framing’ colour (or its absence), querying is role in ‘setting the scene, in unifying the picture, in linking the contents of an image to a series of associative implications and values’ (ibid: 15) and how this may lend itself to tactility through different combinations of visual textures. Issues of interest for the ‘structural’ elements of the drawings were articulated in queries such as: ‘What view, perspective on the given subject-matter does this drawing present?’ Noting the contents of the foreground, middle ground and background, and the interplay between these spatial components.

My identification of issues of interest was informed by an iterative process taking account of insights from my conceptual framing as well as my preliminary readings participant drawings and narratives. Participant interview narratives were analysed using Attride-Stirling’s (Citation2001) thematic analysis of audio recorded transcriptions.

When applying this postcolonial CDA to Lola’s drawing, we see how it is replete with imaginative geographies of ‘difference’ in the ways in which she visualises (the state, context and condition of) Africa and communities therein. Indeed, ‘difference’ is contextualised thematically through her salient perceptions of a somewhat generalised ‘helplessness’, ‘primitivism’ and ‘rurality’ in (and of) Africa, making this place at once distinctly recognisable in her mind’s eye but nonetheless unequivocally peculiar. Analytical discourses of helplessness are evident in Lola’s depiction of African privation, and the instantiation of suffering as shown through the drawing of a fly-swamped, dishevelled, unclothed malnourished child, and the Ebola-and-Aids-alerting hazard warning symbol, for example.

As such, beyond a cursory level interpretation, these elements of her drawing are (and say) more than just ‘a child’ and ‘hazard symbol’ rather, they powerfully historicise her interpretations of Africa(ns) within colonial discourses of forever requiring urgent help, intervention, and consigned to a character of servitude that is agentless and seemingly lacking internal and adequate diplomacies. The depiction of the child reinforces this point, indeed almost all diaspora participants included illustrations of naked or partially clothed children in their drawings, where children have become the quintessential iconographies of human suffering and helplessness in Africa. So much so, that children (and their condition) are proxies of Africa itself. To see a child is to see Africa and vice versa. It is unsurprising then that Lola, and others, included a child in their drawings as a symbolism of Africa’s helplessness much in the spirit and framing of images employed by NGOs in their communications.

Conflating Africa with children and their perceived vulnerability and dependence, infantilises the continent and communities therein. For this participant, her imaginings of Africa as helplessness are constituted in her drawing of the child as some representative of or an idiom for Africa itself. This reveals a colonial discourse of imaginative geographies, whereby Africa is ontologically infantilised. Within this framing, historical metaphors are templated for Africa as childish, as suspended in a state of perpetual toddlerhood waiting for instruction, tutelage and guidance (Manzo Citation2008). This infantilisation, projects Africa as fundamentally different – as ‘Other’ – through its perceived vulnerability, helplessness and inferiority. By infantilisation, I also allude to the paternalism that often undergird postcolonial criticism of Africa as helpless, as the ‘basket case’ that depends on, waits for, Western benign heroism (Shizha and Abdi Citation2014). Such knowledge promulgates solutions for African helplessness informed by Westocentric lenses, whereby a seemingly mature adult Britain, acts in ‘loco parentis’ (as a parent) for a seemingly immature and not-yet-fully-grown, Africa (Manzo Citation2008). As such, in a post-drawing discussion Lola explained how she finds it difficult to comprehend Africa without what she describes as, the ‘give only two pound a month’ child:

‘As soon as I got my colouring pencils I automatically thought about a dying or really really ill child, with a balloon belly and flies buzzing around them, that’s Africa to me. The Africa I see on the telly, you know? The ‘all Fatima wants is an education or future’ type of picture in my mind. That’s what Save the Children and like Oxfam or whatever have taught us, for donkey years …, you can’t think about one without the other, they are paired, Africa and poor kids’.

(Female, 36)

In terms of themes alluding to primitivism (or Africa as primitive), we find examples in Lola’s inclusion of a singular bow and arrow and straw huts in her ‘Africa Map Drawing’ indeed, also includes a depiction of (presumably male) stick figures with the attendant narrative ‘people with stick/spears’. While other diaspora participants drew similar iterations of these things including, as demonstrated in below, Maasai-warrior-esque figures, that are almost-always partially clothed and holding spears and shields. According to the postcolonial CDA interpretation, these ideas of primitivism are founded within visual descriptions and evocations of indigeneity, simplicity (of life) and even tribalism in Lola’s drawing and that of fellow participants, suggesting an imaginative framing and ‘knowing’ of Africa as a geographic space that is somehow backwards, living in the past or ‘lagging behind the times.’

This thematic interpretation is compounded by not just what is ‘seen’ but what is also (consciously or unconsciously) ‘unseen’ or left out. As aforementioned, in terms of the content of drawings, what is significant is both the visible and the omitted, which makes visual methodologies complementary to the interpretative practices of discourse analysis applications. As such, it is worth noting that Lola (indeed ) did not include illustrations of aspects of contemporary societies: the industrial, technological and urban elements of a present ‘here and now’ Africa. Rather, spears were prioritised over mobile phones, and makeshift huts over concrete jungles. This is profoundly meaningful, not least that, Lola’s map drawing provides a symbolic and imaginary capital that confines and defines Africa by a bygone era, that is, Africa exists in a conceptual world where it is solidly anchored in a perpetual state of a prolonged of past. Such imaginings also, by implication, assumes Africa is unreceptive or disinclined to transformation or unwilling to adopt new ideas and if so, not at a pace that is as fast, or as energetic as ever-evolving non-African societies. As Lola shares:

‘I have images in my mind of Nigerian people … or African people in general, as hunter gatherers … hunting for strange forest creatures, fruit or living just in straw huts with stick fires. African cavemen … fetching for water, using firewood for cooking, hunting for fish, things like that, things we haven’t done here in Britain for donkey years. I’ve seen stuff on the telly that show Africa like this, by all these charities and BBC documentaries … that’s why I have a bow and arrow’

Lastly, themes of rurality are evident in Lola’s (and ) illustration of Africa as ‘green’. That is, showcasing patches of foliage and other assumed paraphernalia of the African terrain: trees, forestry, deserts and wildlife. Similar to their interpretations of helplessness and primitivism, diaspora perceptions of their continent/country of heritage as largely rural reflect colonial constructions of imaginative difference. Whereby Africa is understood as a seemingly simple, preindustrialised environment inhabited by rural communities who, despite being hardworking labourers of the soil, are perceived as low-skilled (Dogra Citation2012). Similarly, the homogenisation of Africa as nature-filled and diaspora interpretations of ‘natural-ness’: as unspoilt, deserted land or greenery, casts it as an ‘Other-worldly’ place without any urban or modern features. This consigns it to normative assumptions of timelessness and ahistoricity (Johansen Citation2008).

LIMITATIONS: MIS(AND OVER)INTERPRETATION AND WANTING A ‘GOOD PICTURE’

Despite the many important affordances of drawing methodologies, it also poses some practical challenges regarding its implementation and analytical interpretation. Given the logistical considerations and individualised nature of this qualitative strategy, it is largely unproductive with large groups of participants, thus, samples are often small. As such, while this concern has always been a preoccupation (and quantitative snipe) of qualitative research, it nonetheless affects the generalisability of data produced.

Perhaps, a more substantial limitation of this method is data interpretation. As Silverman (Citation2001) argues, as the method is predominately visual-centric rather than textual (although written narratives often accompany drawing methodologies), it is an incredibly interpretative research method. As such, the legitimacy of validity is hard to evidence. While this can be said for all qualitative forms of knowledge, which invariably go through the sieve of researcher’s subjective interpretation, the parameters of visually-orientated empirical material are generally more open and bound-ary-less than textual strategies and thus is more difficult to interpret. Unintentional opportunities for mis (and over) interpretation are important here. There is a very real danger that the qualitative researcher’s own individual ‘sense-making’ informed by their positionalities (age, sexual orientation, gender, ethnicity, etc.) becomes the criteria upon which interpretative evaluations are made about participant drawings. According to Rose (Citation2001, 16) interpretation must be informed by a ‘critical visual methodology’ which not only pays attention to the image as a visual evidence but also the conditions, relationships and systems of production, circulation and consumption. This importantly includes an understanding that drawings are not isolated, neutral materialisms but products that are fashioned by a researcher’s request.

Within this frame, it is equally incumbent on researchers to acknowledge that participant-produced drawings are contextual, situationally driven and products of their ethno-cultural background, thus are not immune to culturally bias interpretation. As such, the temptation to over (or mis) interpret can be particularly pronounced when the researcher is an 'insider' to the culture(s) of the participant author. This was the case for me as a second-generation British African diaspora, sharing some ethno-cultural similarities with my participants. This is especially true when certain culturally-specific assumptions are made in (and as) interpretations and presented as seemingly self-evident or some sort of authoritative knowledge, relative to similarly-situated and enculturated people and experiences.

In order to alleviate some of the challenge of mis (and over) interpretation, drawing methodologies should be supplemented with other research strategies of knowledge production, both visual and non-visual. This includes, convening post-drawing interviews and focus group discussions, which allow participants to reflect upon the rationalities and processes of sense-making behind their visual products. Not only is this ethical in terms of positioning the researcher to the role of active listener of participant’s narration but it gives them an opportunity to step away from their drawing or inspect it from a different perspective. Written text, written and photo diaries, and mental mapping are also effective triangulating strategies to contextualise participant-produced drawings and open-up new spaces of interpretation (Young and Barrett 2001). Similarly, I found that drawing interpretation is an inherently speculative – assumption-informed activity – thus, it was important that I complemented my cursory level, hypothetical interpretations with the methodological guidance and sophistication of CDA alongside participants’ written and auditory narratives (words and talking).

Finally, another limitation of this research method – especially when implemented with more than one participant – are concerns around the production of a ‘good picture’ and comparing drawings to others. This is something that I contended with. Some participants fretted over their lack of artistic flair or drawing ‘know how’ as compared to other seemingly competent and intuitive drawers. They were worried that this would affect their participation in the research. So too, that I was making certain evaluations about the artistic proficiency of their drawings as some measurement of their accuracy in ‘correctly’ portraying Africa. To address this, it was important to not only reiterate the expectations of my research but also to reassure those (and all) participants that I was interested in the content and context of their drawings and not its artistic quality. Indeed, that all drawings were meaningful for the research.

CONCLUSION

Despite these important limitations, drawing as a participatory qualitative research methodology has immense potential in its instrumentalisation within and across different contexts and abilities. Indeed, its adaptability, inherent originality and comparative straight forwardness means that this non-mechanical strategy is incredibly amendable to and practical for work with children and youth. More importantly, as this article has shown, drawing is highly productive for examining and privileging the empirically understudied and marginalised subjectivities and introspections of adult African diaspora communities. The potential for this visual mode to foster self-empowerment and efficacy among these Black communities, and other participants, enable them to assume active and meaningful contributory roles in the co-production and mediation of their own lived realities, as they ‘see’, feel and ‘know’ it. This affordance makes it a more ethically sound and hierarchically opposing research approach within the vast constellation of qualitative methodologies. Nonetheless, this should not obscure from the reality that more empirical work is needed on both the practical and theoretical implications of this strategy for different types of communities. Optimistically, considering this approach’s progressive application in interdisciplinary qualitative fields, academics and practitioners will document and evaluate such visual participatory modes of knowledge production. With the hope that this will expand the frontiers of our bourgeoning understanding of their potential for and application within the broader field of international social science visual studies.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Edward Ademolu

Edward Ademolu is a Dr of International Development and current Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow in Qualitative Research Methodology, at the London School of Economics (LSE). His interdisciplinary work covers the broad areas of International Development, Media Communications, Representations of Global Poverty and African Diaspora Studies.

Notes

[1] See, LUCAS. 2012. Media Influences on Young People’s Perceptions of Africa.

REFERENCES

- Ademolu, E. 2019. “Seeing and Being the Visualised ‘Other’: Humanitarian Representations and Hybridity in African Diaspora Identities.” Identities 1–21. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2019.1686878.

- Ademolu, E., and S. Warrington. 2019. “Who Gets to Talk about NGO Images of Global Poverty?” Photography and Culture 12 (3): 365–376. doi:10.1080/17514517.2019.1637184.

- Attride-Stirling, J. 2001. “Thematic Networks: An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 1 (3): 385–405. doi:10.1177/146879410100100307.

- Backett-Milburn, K., and L. McKie. 1999. “A Critical Appraisal of the Draw and Write Technique.” Health Education Research 14 (3): 387–398. doi:10.1093/her/14.3.387.

- Bandura, A. 2001. “Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective.” Annual Review of Psychology 52 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1.

- Banks, M. 2001. Visual Methods in Social Research. London, United Kingdom: Sage.

- Campbell, C., M. Skovdal, Z. Mupambireyi, and S. Gregson. 2010. “Exploring Children’s Stigmatisation of AIDS-affected Children in Zimbabwe through Drawings and Stories.” Social Science & Medicine 71 (5): 975–985. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.028.

- Collier, J., and M. Collier. 1986. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

- Dogra, N. 2012. Representations of Global Poverty. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Druin, A., B. Bederson, A. Boltman, A. Miura, D. Knotts-Callahan, and M. Platt. 1999. “Children as Our Technology Design Partners.” In The Design of Children's Technology: How We Design and Why?, edited by A. Druin, 51–72. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Ellard-Gray, A., N. K. Jeffrey, M. Choubak, and S. E. Crann. 2015. “Finding the Hidden Participant: Solutions for Recruiting Hidden, Hard-to-reach, and Vulnerable Populations.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 14 (5): 1–10.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Language, Counter-memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. NY: Cornell University Press.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

- Furth, G. M. 2002. The Secret World of Drawings: A Jungian Approach to Healing through Art – Second Edition. Toronto: Inner City Books.

- Gauntlett, D. 2007. Creative Explorations: New Approaches to Identities and Audiences. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

- Girling, D. 2017. “Radi-Aid Research: A Study of Visual Communication in Six African Countries.” (Norwegian Students’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH) Industry Report). Accessed 06 June 2019. https://www.radiaid.com/radiaid-research

- Gubrium, A., and K. Harper. 2013. Participatory Visual and Digital Methods. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Guillemin, M. 2004. “Understanding Illness: Using Drawings as a Research Method.” Qualitative Health Research 14 (2): 272–289. doi:10.1177/1049732303260445.

- Hook, D., and V.P. Glaveanu. 2013. “Image Analysis: An Interactive Approach to Compositional Elements.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 10 (4): 355 368. doi:10.1080/14780887.2012.674175.

- Johansen, E. 2008. “Imagining the Global and the Rural: Rural Cosmopolitanism in Sharon Butala’s the Garden of Eden and Amitav Ghosh’s the Hungry Tide.” Postcolonial Text 4 (3): 1–18.

- Jupp-Kina, V. 2015. “Exploring the Personal Nature of Children and Young People’s Participation: A Participatory Action Research Study.” Sage Research Methods Cases.

- Kress, G. 2004. “Reading Images: Multimodality, Representation and New Media.” Paper presented at the Expert Forum for Knowledge Presentation, Chicago, IL.

- Kress, G. R., and T. Van Leeuwen. 2002. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London, United Kingdom: Edward Arnold.

- Literat, L. 2013. ““A Pencil for Your Thoughts”: Participatory Drawing as a Visual Research Method with Children and Youth.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12 (1): 84–98. doi:10.1177/160940691301200143.

- MacDougall, D. 2001. “Renewing Ethnographic Film: Is Digital Video Changing the Genre?” Anthropology Today 17 (3): 15–21. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.00060.

- MacGregor, A.S.T., C Currie, and N. Wetton. 1998. “Eliciting the Views of Children about Health in Schools through the Use of the Draw and Write Technique.” Health Promotion International 13 (4): 307–318. doi:10.1093/heapro/13.4.307.

- Mair, M., and C. Kierans. 2007. “Descriptions as Data: Developing Techniques to Elicit Descriptive Materials in Social Research.” Visual Studies 22 (2): 120–136.

- Manzo, K. 2008. “Imaging Humanitarianism: NGO Identity and the Iconography of Childhood.” Antipode 40 (4): 632–657. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2008.00627.x.

- Marett, A. 2005. Songs, Dreamings, and Ghosts: The Wangga of North Australia. Hanover, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- McNicol, S. 2019. “Using Participant-created Comics as a Research Method.” Qualitative Research Journal 19 (3): 236–247. doi:10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00054.

- Mitchell, C., S. Walsh, and R. Moletsane. 2006. “Speaking for Ourselves’: Visual Arts‐based and Participatory Methodologies for Working with Young People.” In Combating Gender Violence in and around Schools, edited by F. Leach and C. Mitchell, 103–111. Stoke on Trent, UK: Trentham Books.

- Papert, S., and I. Harel. 1991. Constructionism. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

- Prosser, J. 2007. “Visual Methods and the Visual Culture of Schools.” Visual Studies 22 (1): 13–30. doi:10.1080/14725860601167143.

- Rattine-Flaherty, E., and A. Singhal 2007. “Method and Marginalization: Revealing the Feminist Orientation of Participatory Communication Research.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the NCA 93rd Annual Convention, Chicago, IL.

- Rose, G. 2001. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. London, U.K: Sage.

- Said, W. E. [1978]2003. Orientalism. UK: Penguin Books.

- Scherer, J. C. 1992. “The Photographic Document: Photographs as Primary Data in Anthropological Inquiry.” In Anthropology and Photography, edited by E. Edwards, 1860–1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Shizha, E., and A. A. Abdi. 2014. Indigenous Discourses on Knowledge and Development in Africa. New York: Routledge.

- Silverman, D. 2001. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analyzing Talk, Text and Interaction. London, United Kingdom: Sage.

- Singhal, A., and E. Rattine-Flaherty. 2006. “Pencils and Photos as Tools of Communicative Research and Praxis Analyzing Minga Perú’s Quest for Social Justice in the Amazon.” International Communication Gazette 68 (4): 313–330. doi:10.1177/1748048506065764.

- Singhal, A., L. M. Harter, K. Chitnis, and D. Sharma. 2007. “Participatory Photography as Theory, Method and Praxis: Analyzing an Entertainment-education Project in India.” Critical Arts 21 (1): 212–227. doi:10.1080/02560040701398897.

- Van Leeuwen, T. 2007. “Legitimation in Discourse and Communication.” Discourse & Communication 1 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1177/1750481307071986.

- Wang, C. 2007. “Youth Participation in Photovoice as a Strategy for Community Change.” Journal of Community Practice 14 (1): 147–161. doi:10.1300/J125v14n01_09.

- Warrington, S, and J. Crombie. 2017. The People in the Pictures: Vital Perspectives on Save the Children’s Image Making. London: Save the Children.

- Weber, S. 2008. “Visual Images in Research.” In In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues, edited by J. G. Knowles and A. L. Cole, 41–54. London, England: Sage.

- Wetton, N. M., and J. McWhirter. 1998. “Images and Curriculum Development in Health Education.” In Image-based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers, edited by J. Prosser, 263–283. London, United Kingdom: Falmer Press.

- Williams, T., N. M. Wetton, and A. Moon. 1989. A Way In: Five Key Areas of Health Education. London, United Kingdom: Health Education Authority.

- Wodak, R., and M Meyer. 2009. Methods for Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Sage.