Abstract

Archival research is haunted by the question of how complete are the archival fonds being consulted. In this article, we describe how we have used a combination of pattern-matching and face-recognition to evaluate the completeness of the Jacques Toussele photographic archive which was established as part of the Endangered Archives Programme at the British Library. A random set of scanned prints from the archive was matched with originating negatives also in the archive suggesting a survival rate of only 30%. Separately, an envelope of negatives from a single event in 1982 was analysed, looking at frame numbers from the surviving negatives. In this case, the survival rate was as high as 70%. Combinations of face-recognition and pattern-matching, for example, of fabric patterns or parts of backdrops, allow us to set some limits to the relative completeness or exhaustiveness of an otherwise relatively undocumented archive.

INTRODUCTION

One of the great uncertainties when undertaking archival research concerns the question of how complete are the archival fonds being consulted. In this article, we describe how we have used a combination of pattern-matching and face-recognition to address this issue in the case of the Jacques Toussele photographic archive which was established as part of the Endangered Archives Programme at the British Library in collaboration with Jacques Toussele and his family.Footnote1 The archive contains some 45, 000 images mainly scans of negatives but including c. 2300 scans of prints. As we demonstrate these techniques also enable other ways to explore the archive.

Most of the literature on face recognition and archives is either exploratory (Charlie Byers Citation2017), looks at implicit bias from the way the training sets were constructed (Smits and Wevers Citation2021) or discusses general issues about the ethical implications of using algorithms in archival management (van Otterlo Citation2017). We are using the technology to evaluate the completeness (also called exhaustiveness) of a single archive of digital scans of the analogue archive of a Cameroonian photographer, Jacques Toussele. One precedent for our sort of approach but not in a visual archive, can be found in Paris and Jäschke (Citation2020).

Completeness in a photographic archive ranges from the sublimely perfect (every image ever taken) to the limiting case of non-existence (we may know of the existence of a photographer without having any example of their work). As we demonstrate in the following sections, like most real cases, the Jacques Toussele archive falls between these extremes. Since the archive contains both negatives and prints, we can measure relative completeness by checking whether for every print in the archive there is a negative. The converse, that for every negative there is there a print in the archive, would not be expected to hold, for reasons that we discuss in the section ‘Types of completeness’ below.

The types of pattern matching and face recognition tools that we have used to evaluate archival completeness in this case have other, more pragmatic applications, when applied to archives such as the one under consideration. They can help with the organisation and annotation of poorly documented archives, identifying, for example, multiple images of the same person as well as multiple images from the same session (examples are included below). The online catalogue is in the process of being updated to include cross-references generated by the use of these tools. We plan to discuss these aspects further in other publications (for examples of applications of our pattern matching tools in other contexts see Dondi et al. Citation2020; Dutta, Bergel, and Zisserman Citation2021), but here we concentrate on the issue of completeness.

PHOTOGRAPHER AND ARCHIVE

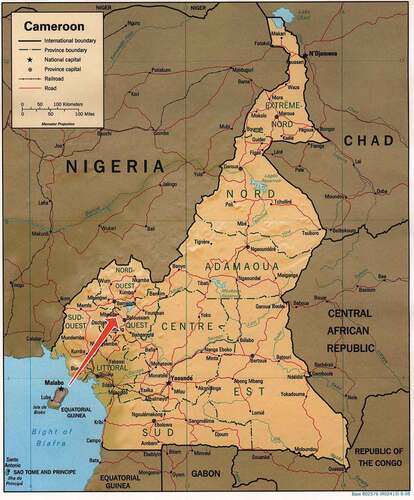

The studio photographer Jacques Toussele was born in c. 1939 in Bamessingué, one of the constituent chiefdoms of Mbouda, Cameroon (he died in Douala on 30 June 2017) in West-Central Africa.

In terms of ethnicity Mbouda is one of the Bamiléké chiefdoms of the Western Grassfields, and the groups around Mbouda are known as the Bamboutous. Jacques Toussele was not the first photographer to work in Mbouda but he was the first local (Bamiléké/Bamboutous) photographer to work there. He was taught photography in 1959/1960 by Ignatius Notchai, who he described as the first photographer resident in Mbouda, but who originally came from Yaoundé (no examples of Notchai’s work have yet been traced). Supplies came mainly from Douala via Bafoussam and after independence from Bamenda through the anglophone supply routes connecting Cameroon’s North-West Province (now Region) to Nigeria. We note that an early photograph of him as a young photographer (included here as Image 1), posed nonchalantly by a box camera on tripod was, according to the stamp on its reverse taken in the nearby city of Bamenda (at Ever Ready Bright Daylight Studio on 21 May 1965). This image was still on display in his studio in 2000, 35 years after having been taken. He spent some time in the early 1960s in Bamenda because of the security clampdown in the area, which was affected by the Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) uprising, and which continued with the help of the French army after Independence (see Deltombe, Domergue, and Tatsitsa Citation2011). More information on the studio and his photographic practice may be found in Zeitlyn (Citation2009, Citation2010, Citation2015), while McKeown (Citation2010) describes the surviving photographic studios in Mbouda in 2006 just before the archiving project started. Zeitlyn (Citation2019) summarises the context of photographic history in Cameroon. Other authors such as Jürg Schneider (e.g. Citation2018) and Chris Geary (e.g. Citation2013) have written about photography in Cameroon. Egloff’s doctoral dissertation (Citation2013) is a detailed examination of the history of photography in nearby Bamenda, some 50 kms from Mbouda, while Tatsitsa (Citation2015) sketches the lives of three photographers from just outside Mbouda. The work of these authors describe the context within which Jacques Toussele worked as a studio photographer. He was active during the boom years (c. 1960–1990) for black and white photography, when passport style photos were needed for id cards and were required on many official documents yet few people had cameras. This was before autofocus cameras and automated processing labs eroded the craft specialisation of photography (long before the digital revolution). The Toussele archive is therefore an instanceFootnote2 of photographic practice during the so-called ‘golden age’ of photography in Cameroon in the years following Independence until the effective end of widespread black and white photography c. 1990.

Originally, they used glass plates but these were replaced by sheet film (plaque plastique in local French) and then medium format film. In several interviews, he made clear his dislike for glass plates: not only would they break but the emulsion was fragile – he said that if left to dry in direct sunshine the emulsion had a tendency to melt and slide off. Following the use of plates (glass and then sheet film) which were taken with tripod cameras such as the one seen in Image 1, he switched to medium format film (120 format). One of the images in his album which sadly is undated (estimated as being c 1970), he remembered as being the first photograph he took with a particular portable camera, a Photax.Footnote3 The image is also in the archive as a copy of the album print, although the original negative has not survived. He used this camera for shots outside the studio, for example, at the weekly markets at different villages to which he and his apprentices (see Image 3) would go with a rolled up backcloth and sometimes a mat to put on the ground.

His apprentices continued to service the markets even after he had established a permanent studio. Indeed, their access to these rural markets is also a testament to his success: the business enabled him to purchase first a motorcycle and then a car (see Image 4). Both feature in several photographs, and not only with Toussele and his apprentices. The motorcycle was sometimes brought into the studio and used as a prop by some clients. Other clients were photographed outside posing by the car as if it were theirs (see Image 5).

Success meant he could graduate from a booth beside the road to having proper studio premises (see Image 6). Before that he was basically itinerant: he had a shelter outside a house but had no proper facilities and worked with sunlight, without an enlarger.

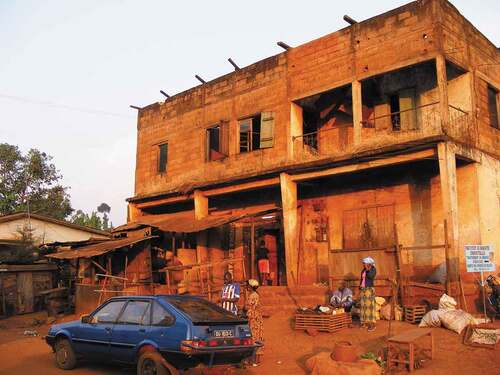

He moved into his first proper studio when main electricity arrived in Mbouda in 1970. He soon moved to a nearby location opposite a bakery which meant there was a steady stream of passing trade and, when necessary, a supply of delivery vans to serve as props. He stayed at that studio from late 1971 until 1994, when he moved up a block to a studio fronting the main arterial road connecting Bafoussam to Bamenda (also close to another bakery). He worked from this studio until the site was redeveloped in December 2006 at which point he retired. Almost all the photographs in the archive date from the second permanent studio (see Images 7, 8, and 9 for a recent shot of the building).

As already mentioned in the early years they were using fragile glass plates, and indeed none of his glass plates have survived. In the early 1960s glass plates were gradually replaced by sheet film, half and then quarter plate-sized negatives. A few sheet film plates survive in the archive but the numbers are relatively low so it seems clear that the coverage of the early years is extremely limited. The bulk of the archive consists of 120 medium format acetate film covering the years 1970 − 1990, and it is the completeness of material from this period that we can begin to consider.

The digital archive is hosted on the British Library websites (copies have been supplied to the Cameroon National Archives and several Cameroonian universities). The Toussele family retain the originals and all commercial rights. Scanning was undertaken in Cameroon with the practical assistance of the British Council. The results are scans of almost 45,000 medium format film negatives and approximately 2300 prints (a mix of c 10 × 15 cm enprints and 4 × 4 cm passport style prints).

We have used two different approaches to assess the relative completeness of the archive. Since the archive contains a small but significant subset of prints (c. 2300) as well as negatives, we can use the prints to test for the completeness of the negative collection by checking whether the negative of a given print is in the archive. This has been made possible by the Visual Geometry Group (VGG – http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/) at the University of Oxford processing the archive contents to create a Cameroon Image Search engine (some early results were reported in Zeitlyn et al. Citation2010).

The Cameroon Image Search engine is a web-based application using current Computer Vision and Deep Learning technology to enable both face-recognition (Parkhi, Vedaldi, and Zisserman Citation2012; Coto and Zisserman Citation2018) and pattern-matching (Arandjelović and Zisserman, Citation2012; Sivic and Zisserman Citation2003; Dutta, Arandjelović, and Zisserman Citation2016) of the images of the archive. The face-recognition search modality enables us to specify a person’s face from an image within the archive (or by uploading another image) and then use it to retrieve all images in the archive containing a similar face, regardless of variations in pose, age, scale or illumination (Cao et al. Citation2018). This allowed us to effectively gather previously unconnected photos of the same person throughout the archive.

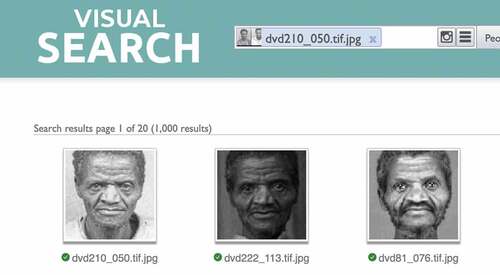

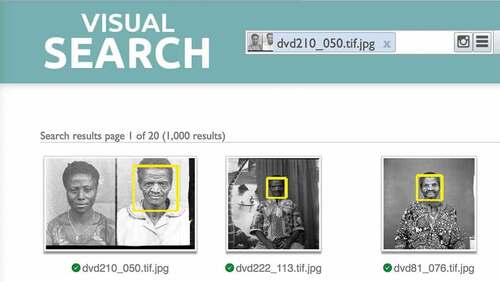

For example, the archive contains three images of one old man, shown in the following images.

Searching on the man’s face from Image 10 finds the results shown in Image 13.

Whichever of the three photos (Images 10–13) is taken as starting point, the other two are the first two hits.

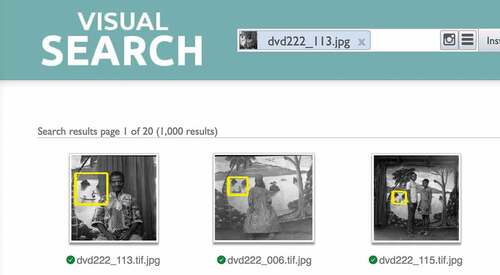

With the pattern-matching modality, we were able to gather images taken in the same studio, at the same location, people having similar clothes or using the same props. This is done by starting from an image from the archive, and selecting a part of the image as input for a pattern-matching search, such as part of the background or the floor, or a piece of cloth, or another feature that might be useful to locate similar images.

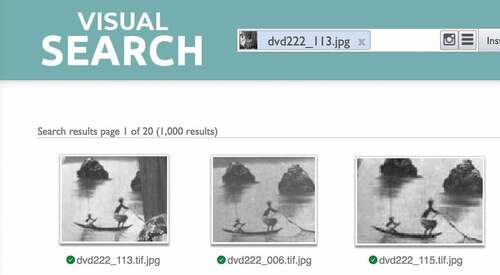

Searching the photograph (shown in Image 11) for a detail of the painted backdrop finds other images using the same backdrop, thus grouping images taken around the same period.

Another example of how this has helped with is the identification of the original negatives for images used as sample prints displayed at the entrance of the photographer’s studio.

The following image was taken in natural light at the entrance to the studio (probably during a power cut). On either side of the sitter we can see sample images which because of a relatively shallow depth of field are not sharply in focus. In some cases, the face is sufficiently clear that face-recognition can identify the original. In other cases, the sample image is too small and too indistinct to have an identifiable face. However, pattern-matching can still identify the original negative from the shape of the figure relative to the background. To do this the sample image was first isolated then unskewed so it was rectangular, with the proportions matching the original. This was then uploaded and used as the basis of a pattern matching search to identify the original negative.

The results obtained from a search can be used as a starting point for another search with either of the two available modalities, so one can move back and forwards between face and pattern searching. All results obtained with the Cameroon Image Search engine can be saved and recovered later if needed. We used the Cameroon Image Search extensively to undertake a consideration of the completeness of the archive. Indeed, without it the evaluations would not have been practically possible.

TYPES OF COMPLETENESS

Inevitably, of course, some shots taken by a photographer are faulty (as indeed are some prints). Although an idealised ‘fantasy’ archive may include every shot ever made by a photographer, few if any photographers would want all their mistakes to be included so a more realistic ideal of completeness might be one of all shots deemed successful. Press and event photographers take many more images than they ever print, so a careful distinction has to be made between ‘successful’ (potentially printable) images that were not printed at the time and those actually printed. The practice of Jacques Toussele and his contemporaries in Cameroon was quite different from this: most of the time a single negative was made for a particular print (especially for the ID photos that comprise a good half of the archive), so in rough terms it was the case that prints were made for almost all the negatives included in the archive, even if we do not have copies of most of those prints (reference copies were not kept).

However, in normal life, there are many reasons why all the successful negatives may not survive in the possession of the photographer and hence may not be archived. These are possible factors (biases in a generic sense) that lead to archival incompleteness. Some of these biases that may be caused by non-random factors. In the case of Jacques Toussele’s practice, one example of a systematic bias comes from the fees charged to clients. There was one charge for a print, a higher fee for print and negative. The possibility of clients paying more for both print and negative could have led to their absence from the archive. However, Toussele said that almost everyone chose to pay the smaller fee and therefore chose to leave the negatives with him, leading to their eventual inclusion in the archive. The only exceptions were the rare occasions when he was called by the police or gendarmerie (different organisations in Cameroon) to take photographs of crime scenes or of arrested suspects. These institutional clients always took both the prints and negatives so left nothing with him for eventual inclusion in the archive. We should note that the documentation of crime scenes does not extend to road traffic accidents: the archive has multiple instances of photographs of car crashes taken for insurance documentation. These were commissioned by the people involved rather than the authorities which is why they survive. Apart from this one instance of systematic exclusion, we have no reason to think there are other categories of photograph that have been systematically excluded from the archive by the clients choosing to take the negatives they had commissioned. Unsystematic loss occurred at random: negatives might get creased accidentally as they were put into storage boxes, they might get dropped when an old negative was being looked for, or a box of negatives might get damp from water from a leaking roof and the emulsion on the outer ones could become damaged.

The question this paper seeks to address is about how comprehensive is the surviving negative collection? In crude terms, does the number of negatives in the archive suggest that this is approximately the number of successful images he took or do we have grounds for thinking it is a fraction of them? If the latter can we reach any estimate of what proportion is included? It is important to know this as a guard against the psychologically alluring tendency to assume that what we have got is all that there ever was. It is simply a mistake to think that any archive contains a complete record. But how good a record is it, what kind of a sample is it? This paper hopes to provide an estimate for the Jacques Toussele archive, which can be plausibly generalised to many of his contemporaries in Cameroon and probably elsewhere in Africa.

Like many photographers in Cameroon Jacques Toussele kept his negatives in case more prints were needed. After printing he stored them (without, it should be noted, any numbering or protective sleeving) in old photographic paper boxes, which were labelled by date. Since negatives clearly from the same studio session or external event were found in different boxes it seems that sometimes after a reprint was made a negative might end up being stored in a different box to the one that it had originally come from.

As has been mentioned, the vast majority of the archive consists of medium format film, the negatives of the prints supplied to clients. The relatively small number of prints that survive represent test prints or ones that were never collected by clients, for one reason or other (such as a lack of cash to pay the bill). This provides a means to test the completeness of the archive since, in principle, the archive should contain a negative for every print found (we note that there are no prints in the archive that relate to photos taken for the police so the bias introduced by the police taking their negatives was not a significant issue for our research. In any case, as already mentioned, on Toussele’s account they were not frequent clients).

SAMPLING PRINTS

A random sample was made of 105 (just under 5%) of the 2157 prints in the archive.Footnote4 We then attempted to match each of these prints with the negatives in the archive.

For 32 of the 105 prints we were able to identify the original negative, suggesting a survival rate of 30%. Additionally, we found 41 instances of possible face matches (photographs of the same individual in other photographs in the archive). Image 17 provides an instance of serendipity: searching for the woman’s face in the left-hand photo found a different print of her standing and the original negative from which that print was made.

There were also nine instances of print and negative matches that also included possible face matches with other photos in the archive. Sometimes these were from the same studio session but where the negatives found were not those of the specific print that was our starting point.

This suggests a surprisingly low survival rate. To test this further, we then considered a group of negatives that had been stored separately.

IMAGES FROM A SINGLE DAY

A subset of images from the Jacques Toussele archive provides another means of assessing survival rates, or the relative completeness of the archive. These were all kept in an envelope apart from the photo paper boxes used to store most of the surviving negatives and prints. The envelope was helpfully labelled with the date (17 December 1982) and a summary name of the event. The images had been taken at a public event, a civic medal giving ceremony for staff at the local agricultural cooperative, the Société Coopérative Agricole des Planteurs de Bamboutos – Mbouda (known as CAPLABAM). Mr Richard Mota, the Prefet of Mbouda, in 1982, the senior administrative officer in the area, presented CAPLABAM members with long labour-service medals: Bronze for 10 Years service, Silver for 20 Years service (19 Years in one certificate seen) and Gold for 25 or 30 years service. In some cases, the same person received both bronze and silver medals at this ceremony (we have seen pairs of certificates from this ceremony and in the photographs some people are wearing two medals).

On the face of it, photography at public events such as this outside the studio could be expected to have a higher failure rate than images taken in the more controlled environment of the studio. People may move when not expected so an arm or head may obscure the view of a medal being pinned onto a chest, a strap may sway and particularly obscure the lens just as the shutter is pressed. So, a higher degree of incompleteness can be expected from any set of films shot at events such as a medal giving compared to photographs taken in the studio.Footnote5

Negatives and Frame Numbers

Consideration of the surviving negatives has enabled us to assess how much has been lost. The following observations come from detailed examination of the negatives and their scans. Like most filmstocks, the edges of the surviving negatives have frame numbers and markings on their edges. Since there are eight instances of frame number 8 it seems that at least eight rolls were exposed by Jacques Toussele and his apprentices. They are all marked SUPER PAN 24, so we know Agfa filmstock was being used. Although 120 roll film is usually said to have had 12 exposures we have frame numbers up to 15, so they seem to have been squeezing additional frames from the films by careful loading. In some cases when cutting the negatives into the standard two-negative-strips which were used for printing and then storage, the cut was not entirely perpendicular so it has been possible to match sets and (almost) reconstitute an entire film roll. There was also some discolouration on the edges of the negatives from light bleeding into the development tank or more likely the camera when the film was inserted or removed which enabled some pairs to be matched and other possible pairings to be rejected.

This has enabled the following reconstruction of a virtual contact sheet included here as Image 18.

This can help give a better idea of rates of survival, of how many negatives were discarded after development as faulty (or have been lost). Unsurprisingly in the circumstances, not a single film roll survives in its entirety. One has only four frames surviving. The gaps in the last two films which were of post-presentation family groups might be because the negatives were used later to make further prints (and then stored elsewhere, although face-recognition has not identified them elsewhere in the archive), or possibly purchased by the families concerned, although such a practice was then extremely rare, as already discussed.

We should note there are two pairs of negatives with frame numbers 1 & 2 and ostensibly four films in which they could occur. However, one pair (186 187) depicts the medal giving line up so must be from Films 1, 2 or 3, leaving the other pair (198 199) to be in one of the post-medal-giving films. Film 7 best matches the wall in the background on the left.

Collating the contact sheet has revealed some anomalies in the numbering: not only the numbering created during scanning but relating to the frame numbers. Because of the pinning of medals on lapels the following photos must work left to right chronologically.

Note scan 239 was taken soon after scan 240 but since it is part of a pair with scan 238 and with the same frame number as scan 240 they must have been from different films. The change in angle also supports this: the man holding the microphone is visible in scan 239 while the secretary has become lost from view. This is evidence of either one photographer using two cameras, or more plausibly that one of the films stored by Toussele was actually taken by one of his apprentices: another image in the archive shows that several photographers were present and shooting during the presentation. One of these has been identified as Tchoffo Pascal, then an apprentice of Toussele.

In chronological terms, scans of 241 must have been taken before 240, and 239 after both of them (the medals pinned on lapels by the Prefet creates a visible, almost literal, timeline) so some negative pairs, including at least those images, were scanned in reverse order (or the scans were saved out of sequence which amounts to the same thing). More significant than the scanning order are the frame numbers which are also not always in sequence. Scan 240 has frame number 5, and scan 241 frame number 6 yet clearly 241 was taken first so it seems that the film must have been loaded backwards in some way, although this seems inexplicable to us (and to the reviewers).

In terms of basic survival rates eight films each of 12 exposures should have yielded 96 images, but it seems they were getting up to 15 exposures per film, so eight films would have had a total of 120 exposures. Only 77 images survive, while 43 (or 36% are missing) giving a 64% survival rate. Had they only obtained 12 exposures per film the survival rate would be as high as 80%.

CONCLUSIONS

These approaches to the archive suggest quite high loss rates from about one-third to more than two-thirds (70%) which implies that the archive may contain less than half of the images originally taken. This raises many questions about the possible factors (biases) leading to archival incompleteness. We have already mentioned some of the non-random factors that may cause such biases, such as the differential fees charged to clients. As noted above, the only times negatives were taken were the rare occasions when he took photos for the police or gendarmerie. Also as noted above, we have no reason to think that other categories of photograph have been systematically excluded from the archive by clients taking negatives as well as the prints. If more routine image making for identity cards and so forth had relatively low levels of survival,Footnote6 then special cases, events like the civic medal presentations, clearly had much higher survival rates: being bundled together and marked with a date in anticipation of orders of multiple prints helped ensure survival into the archival record, although of course this was not the motivation for treating them in this way. So, although photography outside the studio risked more failed shots than when working inside its shelter, the photographers were likely to have compensated for this by taking more shots. Because of the way these particular negatives were stored we think it is plausible that in this instance all the successful negatives have survived. Negatives from several other similar medal giving ceremonies are in the archive and here we suspect they have not been so lucky. It may be that only c. 65% of the original outside shots were deemed successful but of those that were originally kept it is likely that only a third survived to become part of the archive.

Preparing the contents of the studio for scanning to create the digital archive revealed how vulnerable was the source archive: physically the negatives and prints were stored in old photo paper boxes in a back room of the studio and the roof leaked – when the storage boxes were opened several showed signs of deterioration and damage (some negatives had stuck together). As mentioned above most of the negatives are medium format and mainly of high quality (good contrast and well fixed). Many were very dusty and, as just mentioned, some had suffered from damp so it was necessary to wash them before copying (this was undertaken by a former apprentice of Toussele who had recently retired from service as a photographer for the Cameroonian government). Not all survived the process – some negatives had lost all their emulsion in storage, for others the emulsion disintegrated while being washed. Also some prints were stuck together and could not be rescued. Thankfully not many: in addition to the c. 44,000 negatives scanned during the initial archival project about 4500 were initially rejected as being too damaged. From these initial discards a further 3858 images were later added, leaving approximately a further 500 (c.1%) that were not scanned as being beyond rescue (the criteria for scanning in this final phase being whether there was a surviving face in any part of the image).

The special treatment of the negatives from the medal giving suggests that for the archive as a whole the higher rate of loss suggested by the use of face recognition software prevails. So on the basis of our tests we would estimate that between 1970 and 1985 Jacques Toussele and his apprentices took at least 100,000 images and possibly as many as 120,000. The digital archive is incomplete but at least we now have an estimate for the scale of loss.

All archives are incomplete. In this instance at least, thanks to face-recognition and pattern-matching as well as more traditional archival work, we can begin to set bounds to the types and extent of its incompleteness. Any retrieval system will have its own forms of bias, and an emerging literature (examples are cited in the introduction) has begun to explore forms of bias in algorithmically based image retrieval systems. In our case, exploring a single archive of analogue material, the face-recognition and pattern-matching tools provide methods enabling a systematic assessment of archival exhaustiveness.

Map 1. Cameroon. The arrow shows the location of Mbouda. Public domain image https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/africa/cameroon_pol98.jpg.

IMAGE 1. Jacques Toussele and tripod camera. As displayed in his studio, and in his home after retirement: taken at the Ever Ready Bright Daylight Studio 21 May 1965. 2003–4film3_021. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele and David Zeitlyn.

IMAGE 2. Jacques Toussele self-portrait, the first photograph taken with a Photax camera. From Jacques Toussele’s personal album. mbouda_jacques_album_004. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 3. From Jacques Toussele’s personal album: Jacques Toussele with his apprentices Joseph Chila and Jean Bosco Ndanga. mbouda_jacques_album_041. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 4. Signs of success: the photographer with his Renault 4 car. EAP054/1/116/134_dvd154_136. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 5. Senior woman posing by Toussele’s car with signs of rank: e.g. fly whisk and palm wine gourd EAP054/1/124/343_dvd115_053. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 6. Jacques Toussele at his booth. mbouda_jacques_album_086.gif. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 7. Clients posing with motorcycle outside the Photo Jacques studio. EAP054/1/125/181_dvd174_067. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 8. Outside the Photo Jacques studio EAP054/1/123/56_dvd124_117. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 10. Doubled exposure on one plastic plate: two individuals for ID cards. EAP054/1/152/339_dvd210_050. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 11. Note painted backdrop on left hand side. EAP054/1/176/169_dvd222_113. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 13. Results of face-matching, searching with the face of the man in Image 10. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele and VGG. (a) Results of face-matching, searching with the face of the man in Image 10. Using option to show only matching faces. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele and VGG.

IMAGE 14. Results of pattern-matching part of the backdrop (highlighted). Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele and VGG. (a) Results of pattern-matching part of the backdrop. Using option to show only matching sample. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele and VGG.

IMAGE 15. Photo taken at the door to the studio with display board images visible. EAP054/ 1/7/331_dvd311_119. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele. (a) Detail of display-board images from Image 15 ‘unskewed’ so the images are rectangular. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 16. (a) Target for pattern-matching extracted from Image 15. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele. (b) Source negative for Image 16a /EAP054/1/164/46_dvd182_106. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 17. An instance of serendipity: searching for the woman’s face in the left hand photo finds a print of her standing and the original negative from which that print was made. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele and VGG. (a) An instance of serendipity: searching for the woman’s face in the left hand photo finds a print of her standing and the original negative from which that print was made. Using option to show only matching faces. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele and VGG.

IMAGE 18. Caplabam medal-giving reconstructed contact sheet. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 19. (a) dec82cap_241 frame number 6. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele. (b) dec82cap_240 frame number 5. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele. (c) dec82cap_239 frame number 7. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

IMAGE 20. Detail of dec82cap_224 showing photographers attending the ceremony on 17 December 1982. Photographers in this image: Left hand edge Photo Jazz (Ngwamorgna Boniface) possibly with a Chinese Seagull camera qv DSCF1012 from 2016, mid left at back: unknown/not recognised; Centre bending over = ‘Boney M’ (reported to be in Douala in 2016); Right hand side in cap is the photographer Darasang. Tchoffo Pascal has been tentatively identified in another image (182) from the same event. Reproduced courtesy of Jacques Toussele.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The face-recognition and pattern-matching software used during this work was supported by the UK EPSRC under programme grant Seebibyte: Visual Search for the Era of Big Data (EP/M013774/1) and correspond to variants of the VGG Face Finder (VFF) (Coto and Zisserman Citation2018) and the VGG Image Search Engine (Dutta, Arandjelović, and Zisserman Citation2016). The creation of the Jacques Toussele archive was supported by the British Library Endangered Archives Programme ‘Archiving a Cameroonian Photographic Studio’ under grant EAP054. Work in Cameroon was done in collaboration with Jacques Toussele and his family: we are very grateful to them for their help and cooperation. The work in Cameroon was institutionally supported by the Cameroon National Archives, The British Council and Adonis Milol at AAREF.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

David Zeitlyn

David Zeitlyn has been doing research in Cameroon since 1985. He has worked with photographers in Mbouda and in the area near Somié where he has also done extensive ethnographic research. A monograph on Mambila spider divination was published in 2020. He is co-curating an exhibition of the work of Jacques Toussele and two other Cameroonian photographers to be held at the Fowler Museum, Los Angeles in late 2021. https://www.fowler.ucla.edu/exhibitions/photo-cameroon/

Ernesto Coto

Ernesto Coto is currently a Senior Software Engineer at Optellum Ltd., working with lung cancer detection technologies. Before that he was a Research Software Engineer at the Visual Geometry Group in the University of Oxford as a key member of the Seebibyte Project, a research effort developing next-generation Computer Vision methods. He was a Lecturer at the Central University of Venezuela (UCV) for many years but also has professional experience as a Software Developer for a range of companies and other universities. He has co-authored numerous scientific articles published in international journals and congresses. He has also organised international conferences, done peer-reviewing for numerous scientific events and is the co-inventor of one pending patent in the UK.

Andrew Zisserman

Andrew Zisserman is a Royal Society Research Professor at the Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford, where he heads the Visual Geometry Group (VGG). His research has investigated and made contributions to multiple view geometry, visual recognition, and large scale retrieval in images and video.

Notes

[1] The Jacques Toussele archive has been licenced for non-commercial, teaching and research use, and is accessible online via https://eap.bl.uk/project/EAP054. Commercial rights are reserved.

[2] In principle, but one example of many but few others survive: the Photo George studio in Douala (covering a wider period time, going back well before independence) is being archived as is (it is hoped), that of Kameni Michel in Yaoundé (with similar scope to the Toussele archive). Relatively small archives (c. 2000 images each) from Joseph Chila and Samuel Finlak covering the same period as Jacques Toussele have been created (in 2021 these are held by Autograph in London).

[3] Boyer Photax III ‘Blindé’, produced 1938–1946 M.I.O.M., Vitry-sur-Seine, France. See http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Photax. Image 20 shows photographers using what seem to be Chinese Seagull cameras.

[4] Like any database which is being actively developed the numbers are in some flux. We note that subsequent to doing the research reported in this paper, more work on the catalogue identified a significant number of prints that had been wrongly labelled as negatives, increasing the notional number of prints which was subsequently reduced by the identification of duplicate scans at different resolutions. So although we were aiming at 5% we have only actually sampled 4% of the 2335 unique prints in the archive. We can find no reason to think this would make a significant difference to the research reported here, so we have left the original numbers as they were in 2019/early 2020.

[5] We are very grateful to one of the anonymous referees for pointing this out.

[6] A referee asked whether ID card photos were not cared for since they would become outdated, and new photos would be required for replacement ID cards. While that is the case, there is a cultural factor that mitigates against this: old photos (often enlargements of ID card images) are paraded and displayed at post-mortem funeral celebrations (cry-die or funerailles) in this area. Jacques Toussele regularly made large prints for these events.

REFERENCES

- Arandjelović, Relja, and Andrew Zisserman. 2012. “Three Things Everyone Should Know to Improve Object Retrieval.” Paper presented at the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Juan, PR, USA.

- Byers, Charlie. 2017. “Facial Recognition in the Archives “Can You Identify Anyone in This Photograph?”” Accessed 28 March 2021. https://charliebyers.org/facial-recognition-in-the-archives/

- Cao, Qiong, Li Shen, Weidi Xie, Omkar M. Parkhi, and Andrew Zisserman. 2018. “VGGFace2: A Dataset for Recognising Faces across Pose and Age.” Paper presented at the International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition, Xi'an, China.

- Coto, Ernesto, and Andrew Zisserman. 2018. “VGG Face Finder (VFF).” http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/software/vff/

- Deltombe, Thomas, Manuel Domergue, and Jacob Tatsitsa. 2011. Kamerun ! Une guerre cachée aux origines de la Françafrique. 1948-1971. Paris: La Découverte.

- Dondi, Cristina, Abhishek Dutta, Matilde Malaspina, and Andrew Zisserman. 2020. “The Use and Reuse of Printed Illustrations in 15th-Century Venetian Editions.” In Printing R-Evolution and Society 1450-1500: Fifty Years that Changed Europe, edited by Cristina Dondi, 839–869. Venice: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari - Digital Publishing. doi:10.14277/978-88-6969-332-8/030.

- Dutta, Abhishek, Relja Arandjelović, and Andrew Zisserman. 2016. “VGG Image Search Engine (VISE).” http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/software/vise/

- Dutta, Abhishek, Giles Bergel, and Andrew Zisserman. 2021. “Visual Analysis of Chapbooks Printed in Scotland.” In 6th International Workshop on Historical Document Imaging and Processing (HIP’21), Lausanne, Switzerland, September 6.

- Egloff, René. 2013. “Fotografie in Bamenda: Eine ethnographische Untersuchung in einer kamerunischen Stadt.” PhD, Faculty of Humanities, University of Basel. http://edoc.unibas.ch/diss/DissB_10617.

- Geary, Christraud M. 2013. “The past in the Present: Photographic Portraiture and the Evocation of Multiple Histories in the Bamum Kingdom of Cameroon.” In Portraiture and Photography in Africa (African Expressive Cultures), edited by John Peffer and Elisabeth L. Cameron, 213–252. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- McKeown, Katie. 2010. “Studio Photo Jacques: A Professional Legacy in Western Cameroon.” History of Photography 34 (2): 181–192. doi:10.1080/03087290903361506.

- Paris, Michael, and Robert Jäschke. 2020. “How to Assess the Exhaustiveness of Longitudinal Web Archives: A Case Study of the German Academic Web.” In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media, 85–89. Association for Computing Machinery.

- Parkhi, Omkar M., Andrea Vedaldi, and Andrew Zisserman. 2012. “On-the-fly Specific Person Retrieval.” Paper presented at the 13th International Workshop on Image Analysis for Multimedia Interactive Services, Dublin, Ireland.

- Schneider, Jürg. 2018. “Views of Continuity and Change: The Press Photo Archives in Buea, Cameroon.” Visual Studies 33 (1): 28–40. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2018.1426224.

- Sivic, Josef, and Andrew Zisserman. 2003. “Video Google: A Text Retrieval Approach to Object Matching in Videos.” Paper presented at the Proceedings Ninth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Nice, France.

- Smits, Thomas, and Melvin Wevers. 2021. “The Agency of Computer Vision Models as Optical Instruments.” Visual Communication 147035722199209. doi:10.1177/1470357221992097.

- Tatsitsa, Jacob. 2015. “Black-and-White Photography in Batcham: From a Golden Age to Decline (1970–1990).” History and Anthropology 26 (4): 458–479. doi:10.1080/02757206.2015.1074899.

- van Otterlo, Martijn. 2017. “From Intended Archivists to Intentional Algivists: Ethical Codes for Humans and Machines in the Archive.” In Archives in Liquid Times, edited by Frans Smit, Arnoud Glaudemans, and Rienk Jonker, 267–293. ’s-Gravenhage: Stichting Archiefpublicaties.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2009. “A Dying Art? Archiving Photographs in Cameroon.” Anthropology Today 25 (4): 23–26. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8322.2009.00679.x.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2010. “Photographic Props/The Photographer as Prop: The Many Faces of Jacques Toussele.” History and Anthropology 21 (4): 453–477. doi:10.1080/02757206.2010.520886.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2015. “Archiving a Cameroonian Photographic Studio.” In From Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives, edited by Maja Kominko, 529–544. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2019. “Photo History by Numbers: Charting the Rise and Fall of Commercial Photography in Cameroon.” Visual Anthropology 32 (3–4): 309–342. doi:10.1080/08949468.2019.1637683.

- Zeitlyn, David, Ananth Garre, C. V. Jawahar, and Andrew Zisserman. 2010. “The Archive. Where Is the Archive?” Photography & Culture 3 (3): 331–342. doi:10.2752/175145109X12804957025679.