Abstract

Street art in the Indonesian city of Yogyakarta is popular, dynamic and vibrant. Like other cities such as Buenos Aires, it has become something of a tourist attraction in its own right. This article examines Yogyakarta street art as a visual phenomenon that activates political change potential in three ways. First, it provokes the critical consideration of ordinary people who pass by the walls and surfaces of the city every day. Second, it suggests alternative futures within the context of achieving social justice and redress of past wrongs. Third, it challenges the mainstream elite artworld of Indonesia that is anchored in galleries and commodification. Street artists constitute their grassroots art practice collectively, offline and online. Data was gathered ethnographically over two years. Analysis of data proceeds in the form of rhizoanalysis, in keeping with a non-representational framework drawn from the work of Deleuze and Guattari. The street art of Yogyakarta is considered as an assemblage, one characterised by the creative process of (political) becoming. The street artworks generate meaning through visual juxtapositions, gags and texts that imply lines of flight into a future generated by radical questioning. We argue that Yogyakarta street art can be read as a form of rebel imaginings.

INTRODUCTION

The premise of this paper is that Yogyakarta street art can be read as a form of rebel imaginings. The rebel imaginings of the Yogyakarta street artists emerge from their desire for political change, and from collaborative practices that generate new ways of doing and being – artistic, social and political. At the same time, the artworks they create in the streets of Yogyakarta visually stimulate the rebel imaginings of passers-by, who engage with the artworks, in part by reading and re-reading them through a distinctively local lens of socio-cultural interpretation. The concept of rebel imaginings thereby offers a way of explaining the subversive nature of Yogyakarta street art and how it may produce desire for change in the local population (see Mansfield Citation2020). Rebel (or rebellious) refers first to the minority status of street art in a city renowned for traditional fine art, and second to the provocative content of the artworks, anchored to past and present political events in ways that suggest much greater democratic practice, social justice and equality of opportunity. Imaginings refers both to the artists’ desire to create subversive surfaces, to visualise thought provoking versions of the past, present and future, and to their collective desire to cue that same kind of critical and alternative visualisations in local citizens, and perhaps beyond.

INTERPRETIVE FRAMEWORK

To advance our arguments, we make use of an interpretive framework built from the conceptual work of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. While studies of contemporary art using their framework have been conducted (see O’Sullivan Citation2010), little relevant consideration of street art has taken place. Similarly, while studies of alternative arts scenes in Indonesia have been conducted using a framework drawn from Deleuze and Guattari (see Martin-Iverson Citation2014), that kind of interpretation has not been applied to the collective practices of street art in Indonesia. The collective practices in this case constitute an interdependent component of connectivity between material and non-material aspects of the street art assemblage. These Indonesian street artists come together in an informal, unstructured and organic collectivity. This article broaches new ground in investigating these creative practices.

We propose that the street artists, their collectives, the engaging audience, the artworks themselves, and even the city of Yogyakarta itself, constitute an ‘assemblage’; one from which ‘lines of flight’ may emerge to illuminate new possible futures and the redress of past wrongs. Throughout the work of Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987), assemblages are framed as non-hierarchical, multifaceted arrangements of materials, bodies, expressions and actions joining together. The joining up process is one of fixing or fitting – sometimes fleetingly – to enact new ways of operating, and to generate further meanings. Desire is all-important: ‘An assemblage does not exist without the passions the assemblage brings into play, without the desires that constitute it as much as it constitutes them’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987, 399). In the production of artworks in Yogyakarta, street artists desire/want to activate shock. They provoke and disrupt (Zabala Citation2017) through unexpected visual juxtapositions of the beautiful and the ugly, of ancient myths and urban slang, of quaint nostalgia and stark intimations of mortality. Thus, within a street art assemblage, desire – made manifest in the provocative articulation of political forces, thoughts and actions – produces both the creative identities of street artists, and the lines of flight that signify rebel imaginings. The process is one of becoming; the constitution of change, flight, or movement within an assemblage. In ‘becoming’, elements of the assemblage may be drawn into new orders and values of meaning; into new territory which implies a different set of possibilities. In that sense becoming points to ‘deterritorialisation’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987, 272), a line of flight which may ultimately lead to a new assemblage forming in the rhizomic network of the broader phenomenon.

Conceptually, the term ‘lines of flight’ describes the movement of an idea, a practice, a desire; a creative impulse that seeps, leaks, flees or escapes from an assemblage. According to Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) lines of flight can rupture out and away from the established arrangements of an assemblage. Their departure charts a new plane of radical possibility; of ‘becoming’ – which has no absolute starting point or endpoint (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1994). Lines of flight invite new opportunities for change and transformation. Thus, in Yogyakarta, new grounds for meaning-making emerge as the street art collective regroups and re-assembles its practice; as groups of citizens are prompted into lobbying and advocacy. Nevertheless, any line of flight that invites a new imagining or creative potency is not unconnected to the ‘parent’ assemblage from which it came. Thus, any autonomous artwork in public space implicitly encodes potential for ‘transformative visual dialogue in everyday life’ (Awad Citation2020, 28). In the view of McCormick et al. (Citation2015, 1), unsanctioned public art remains ‘the problem child’ of cultural expression, still an outlaw among visual disciplines. Accordingly, street art in Yogyakarta has an abundance of ‘rebel’ potential; to upset the established artworld, and to stimulate the conditions for social change.

Notably, the street art of Yogyakarta has no centre, no focused organisational hub. The artists are nomadic. They roam about the city, engaging with ordinary people in communities, making art where it is not supposed to be, using whatever comes to hand for inspiration and materials. They pop up in unexpected places, like a living subterranean network. In the work of Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987), the metaphor of the ‘rhizome’ speaks to that kind of relational ontology. In nature, the rhizome is a subterranean root-like stem that spreads nomadically and manifests as nodes of the plant that appear above the surface. Metaphorically, rhizomes are ‘always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987, 25). Thereby, decentred rhizomic connections produce unexpected, non-hierarchical associations between various elements. Any element within the rhizome may form networks with any other part. Yogyakartan street art collectives may be understood as eminently rhizomic in nature, since elements of practice and content are always in hyper-connected flux, de-territorialising and re-territorialising fine art traditions, urban space, political desires and national histories.

In theoretical terms, street art, as an act of puissance, is a contributor to potentially subversive political discourse. In French, puissance refers to power from below, while pouvoir refers to power from above (see Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987). In the context of street art as visual activism, art practice operates in the domain of puissance where subaltern power resists the pouvoir of dominant agents above; in the State and formal institutions, as well as in the mainstream world of contemporary and fine art. We propose that street art collectives encode the kind of subversive potential intended by Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) in their framing of the minor or ‘minoritarian’ art/science/literature, which contrasts with the normative major or ‘royal’ art/science/literature – sanctioned and colonised by the State. While a major art operates within the domain of pouvoir to maintain and further the status quo, a minor art exercises puissance to challenge the status quo. Minor art is connected to radical possibilities because it constitutes the potentially transformative process of creative becoming; ‘all becoming is minoritarian’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987, 106). Yogyakartan street art collectives exemplify minor art. They are located outside the hierarchical status structures of the official artworld; the formal showings, contemporary galleries, museums, marketing strategies, and privileged audiences that recognise and reward individual artistic merit (Young Citation2016). Street art concerns itself with the commonplace while transfiguring common places (Riggle Citation2010). Our empirical research suggests that as artistic endeavours in Yogyakarta are largely untethered from individual talent appraisal and processes of commodification, they evade capture by the capitalist economy and the status/reward mechanisms of the State.

RESONANCE AND REMEMBERING

Anywhere in the world, art on the street is often subversive and frequently political. For example, Baudrillard (Citation2016, 99) draws attention to instances in which urban graffiti can ‘burst into reality like a scream, an interjection, an anti-discourse’. Street art is ‘public art; it’s accessible; it’s of the people; it’s an urban voice; it’s on public view; it’s on-the-street’ (Philipps, Zerr, and Herder Citation2017, 382). Pan (Citation2015, 5), writing about the visual politics of graffiti in East Asia, notes that street art reflects ‘the collective memories of a particular society’. That includes democratic movements (Ulmer Citation2017). Yogyakarta street artworks likewise make striking visual reference to the past of the Indonesian nation; to the independence struggle and to the later struggle for democracy. They encode visual cues relevant to the silencing of dissent in both those struggles, and in later political events, including corrupt and unregulated urban development. Heryanto (Citation2014, 7) argues that Indonesians ‘have suffered from serious historical amnesia’. ‘Silenced’ events include the anti-communist mass killings of 1965–66 and the assassination of key activists in the 1990s. In Indonesia, visual artists play a key role in remembering the hidden past, and this can create tensions between artists and authorities (George Citation2005). Street art stretches that challenge to the limits, practised as it is on technically illegal urban spaces controlled by government and private enterprise.

In the field of artistic expression, visual depictions of the politically fraught past can be described as ‘remembering’ or making the people ‘remember’. However, they can also be considered as creating an unsettling visual resonance to suggest a new becoming. ‘Resonance’ is the term used by Khasnabish (Citation2008) to describe the process by which the Zapatista movement in Mexico retains its political potency over time. For Khasnabish, resonance is the non-linear dynamic by which meaning made in one context becomes significant in another context, and thereby gains the political potency to create ‘new political spaces, practices and subjectivities’ (Citation2008, 36). Khasnabish uses the work of Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) to show how the ‘minor’ literature of the Zapatistas works through the evocation of resonances to constitute an ongoing ‘line of flight’ into the field of ongoing revolutionary struggle in Mexico (Khasnabish Citation2008, 41). In a similar way, affective resonances produced by the visual puissance of Yogyakarta street artworks revitalise democratic process to provoke radical questioning by the ordinary people, in Javanese, the wong cilik of the city.

LOCATION OF THE STUDY

The city of Yogyakarta in Central Java has a lengthy history as a thriving art centre with a vibrant traditional and contemporary art scene often intermixing to produce new innovative styles. Home to many prestigious educational institutions, Yogyakarta attracts students from across Indonesia. Those elements coalesce to make Yogyakarta a youthful, exhilarating and dynamic city. However, all those elements, as well as world-heritage-listed monuments and a renowned performance and arts/crafts movement, have consolidated Yogyakarta as a tourist mecca, leading to much corrupt, unregulated development of tourist accommodation and leisure facilities. In essence, the attractive city of Yogyakarta, rather like Venice and Dubrovnik, risks being destroyed by tourism. Street art in Yogyakarta visually depicts that contemporary phenomenon, embedding it in imagery and symbolism that calls on the past to change the political future (Irianto Citation2001). Themes of revolution, nationalism and poverty are common (Berman Citation1999; Supangkat Citation2005) in the visual activism of Yogyakarta artworks, often signalled in symbolism, words and slogans.

A brief history of Yogyakarta street art

In Yogyakarta, street art is a more or less collective public activity and has always been dominated by men. That is not surprising given the traditional gender order of the archipelago, where women occupied a subordinate role, located primarily in the private domain of the home. The streets, especially at night, are regarded as risky space for women (Nilan et al. Citation2014, 871). In historical terms, the street art collectives of Yogyakarta follow the centuries-old Javanese royal court tradition of a group of men making religiously-oriented art in dedicated space – sanggar – under the guidance of a senior, revered artist. That tradition avoided attribution to individual visual artists (Geertz Citation1990). A new sanggar movement emerged after Indonesia finally gained independence in 1945. Once again, senior artists mentored groups of young men to bring their ideas, inspirations and experiences to visual realisation in a formal, highly structured arrangement (Dahl Citation2016, 114). The new sanggar art collectives were inspired by the traditional peasant-class principles of gotong royong – mutual assistance, and musyawarah – negotiated consensus (Bowen Citation1986, 545). Later, during the authoritarian Suharto era, many sanggar were labelled subversive, and were targeted by anti-communist militias (Dahl Citation2016, 114). Yet the sanggar tradition survived and is now associated with groups of traditional performing and visual artists. For the street artists in Yogyakarta, elements of the sanggar artistic practice lives on in the bonded solidarity of their collectives, where senior practitioners of the genre guide junior artists. However, these contemporary collective practices are more informal and fluid than the traditional sanggar forms.

Yogyakarta street art collectives are part of the alternative art movement in Indonesia, so there is no doubt they owe a debt to the original New Art Movement, Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru, which emerged in the 1970s. In major cities across the nation, but particularly in Java, there was on-going art student rebellion against the modern and decorative art taught in the art academies that were sanctioned by the Suharto regime (Ingham Citation2007, 1). By avoiding contention and concentrating on the market, the mainstream art world at the time was held to support the oppressive Suharto dictatorship (1966–1998). Young 1970s artists rejected art focused on formal properties recognised by the high culture art world where both artworks and artists were marketed and commodified to generate profit. Recognising that many Indonesians have no tradition of visiting galleries (Turner Citation2005), and might well be intimidated by architectural buildings and security guards, local art collectives used interactive projects such as colourful murals to address issues of community concern. Art crews created collaborative works that brought the lives and concerns of the rakyat kecil (in Indonesian: little people or urban poor) to the fore in public space (Berman Citation1999; Lee Citation2013). To obtain those visual stimuli, they reflectively roamed about in urban areas, seeking inspiration, for example,

With sketchbooks in our hands, we explored the streets of Jakarta (…) What were the points of attractions from Senen and Jatinegara to us at that time? What did we get from such experience? (Nashar Citation2002, 100–101).

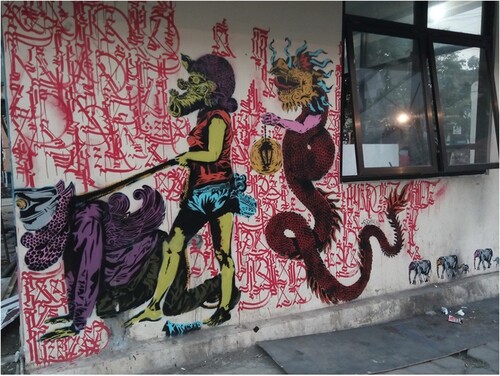

Contemporary decorative graffiti began to appear across Indonesian cities in the 1980s (Lehman-Schultz Citation2009). By the early 2000s, a vibrant contemporary mural street art scene had emerged in the Javanese cities of Jakarta, Bandung and Yogyakarta (Zaelani Citation2001). Street art practice in Yogyakarta today entails a wide range of techniques including tags, throw ups, posters, stencils and more large-scale mural pieces. It should be noted that, until quite recently, the availability of spray cans was limited and expensive. Artists used house paint and this gave street art in the city a distinctive look – which has endured. The cost and availability of materials encouraged postering and stencil techniques rather than the large painted mural pieces more common in the West. The conditions of the urban environment also shape street art in the city. Walls, lanes, roads and billboards, as well as traffic flow, become elements of the artwork. The culture and history of Yogyakarta, including old and crumbling buildings, facilitate or impede creative endeavours in the streetscapes. In the artworks themselves, imagery from ancient Ramayana puppet plays, contemporary advertising symbols, and raw political propaganda, are reworked to generate parody and satire. This is a wider trend in the street art of the East Asian region, which tends to celebrate the ‘carnivalesque humor and disorder experienced by [local] people in their daily lives’ (Pan Citation2015, 7). In Yogyakarta street art it is not uncommon to see depictions of village subsistence hardship side-by-side with mythological creatures from ancient Javanese cosmology. Such syntheses are intended to resonate with the immediate knowledge frames of people passing by (see ).

shows a large work on a city wall by street artist Anagard. The creatures drawn from local ancient mythology engage critical commentary on air pollution (the apparent gas mask muzzle), and economic oppression (the yoked and crawling Garuda, avian symbol of Indonesia). The red and white background detail resembles writing in Kawi, the old Javanese language. Red and white are the colours of the Indonesian flag.

Street art is, by definition, ephemeral. Artworks may be disfigured, painted over or removed; walls may be torn down. Yet the artworks survive in photographs, in images printed on a t-shirt, or in hard copy re-prints sold to the public. Extension of street art life has been further amplified by the emergence of internet technology and digital media in the first decades of the new millennium (MacDowall and de Souza Citation2018). As Bengtsen (Citation2014) points out, widespread photographic documentation of street art and dissemination of images online speak to a global audience. Through digital technology, today practitioners and audiences worldwide may engage with the work of Yogyakarta street artists and download it for their own purposes.

METHODOLOGY

An ethnographic approach was employed to collect data on street art and street artist collectives in Yogyakarta. That entailed intensive fieldwork, where the researcher directly participates in activities in the field to gain as much of an insider’s viewpoint as possible (Walter Citation2010), and to enable the ‘thick description’ that generates ‘rich’ data (Geertz Citation1973). While conducting fieldwork in 2014–2015, the first and third authors engaged in a great deal of nongkrong – the local cultural version of hanging out and chatting informally (Crosby Citation2013; Geertz Citation1998). Nongkrong – in the form of deep hanging out – is essential practice in Yogyakarta art collectives.

For many of Yogya’s artists, nongkrong is an essential aspect of how both their art practices and communities function and flourish. In the words of one such artist, ‘Nongkrong is our school’. Its looseness allows for an open and generous exchange of ideas and information, a casual knowledge-sharing (Dahl Citation2016, 108).

The particularly non-productive time that characterises artist nongkrongs in Yogya also distinguishes them from the ultra-productive, CV-loading and so-called ‘professionalised’ track that highly capitalist systems encourage from artists (Dahl Citation2016, 113).

Interview transcripts in Indonesian/Javanese were translated by the second and third authors. Field notes and visual records (see Henderson Citation2008) were kept by the first author during visits to Yogyakarta in 2014–2015, and subsequently in online follow-up with artists and informants. Pink (Citation2013) advocates that kind of reflexive approach when using visual methodologies. Reflexivity implies an attempt to see knowledge, including visual knowledge, as contextual and partial rather than governed by grand narrative (Rose Citation2012). The visual ethnographer must consider not only images but also their local cultural conventions and social meanings, as well as the context of the researcher themselves. Photos of Yogyakarta artworks and collective practice were organised by date, context and location to facilitate an ordered and systematic appraisal, and for later cross-referencing of themes and events. The photos were used by the first author in a number of ways: as an ‘aide-memoire’ or set of visual field notes; as a source of data in their own right; and as a photo-elicitation resource to prompt discussion by research participants in interviews and focus groups (Bryman Citation2012, 457).

To give a broad coverage of the Yogyakarta street art assemblage, 63 informants were drawn from the city’s street artists, and local people (the audience), fine art practitioners and arts administrators. Some were interviewed individually and some in focus groups. Both visual and interview data were analysed and interpreted using rhizoanalysis, which incorporates discourse analysis and visual analysis. A rhizoanalytic approach sidesteps assumptions about cause and effect; intention and reaction, since the rhizome is ‘always … intermezzo’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987, 25). A rhizoanalytic interpretive approach was found to be productive for examining the structural and counter-structural forces and flows of intensity (see Massumi Citation2002) that shape the street art assemblage, as well as lines of flight that pointed to radical questioning (see Tamboukou Citation2010). Rhizoanalysis invites a shift beyond traditional methods of analysing visual arts. According to Masny (Citation2014, 351), the ontology of rhizoanalysis is ‘anti-representational’. A visual image is never considered a pure reflection or representation of reality (St. Pierre Citation2004). Instead, any image is acknowledged to be a cultural construction encoding norms, values, symbols, contexts and histories, as well as practices of production, reception and viewing (Taylor Citation2013). Moreover, it exists as a component of a wider flow. Adopting a rhizoanalytic approach allowed the researchers to see that the assemblage of street art flows and disseminates meaning in a rhizomic, non-linear way, unlike a structured sequence of art pieces in the formal artworld.

RAISING THE DEAD

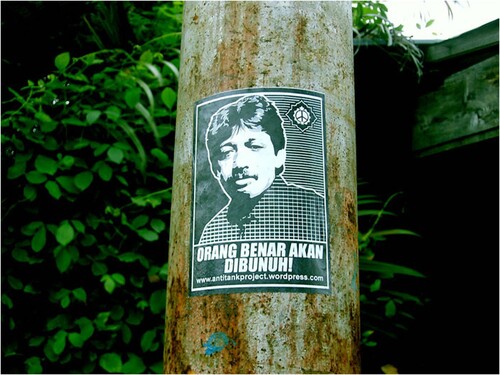

By rupturing official sanctioned histories, the lines of flight emerging from a street art assemblage can inspire political actions to challenge long suppressed truths. In 2014, an election year, Yogyakarta street artists Digie Sigit, AntiTank and others produced works on murdered political activists using a variety of mediums. They did so both individually and collectively. For example, AntiTank used a simple poster to disseminate an image of human rights and anti-corruption activist Munir Said Thalib, who was assassinated in 2004 while travelling by plane to Utrecht University to pursue a master’s degree (see below).

Recuperation of historical memory often features in the critical street artworks of Digie Sigit (see ). Sigit’s Munir stencil was created from an old newspaper photograph. It is stark in its simplicity and designed for both repetition and instant recognition by the public. Digie Sigit’s Munir stencil work on the streets of Yogyakarta was striking when the simple image was repeated horizontally in lines along the concrete walls which form a backdrop to commuter routes and daily shopping activities.

Figure 3. Kami tetap ada dan berlipat ganda – We remain and our numbers are increasing (Artist: DigieSigit).

Later, the same stencil was juxtaposed with another Digie Sigit stencil to further refine the call to political conscience (see ).

The stencilled little girl can be read as a symbol of the new generation remembering the murder of Munir back in the past. That inclusion, and the text, bring the street artwork into the contemporary moment. Thereby, murdered truthseeker Munir becomes relevant to the new generation of young people. Young people who view the work in passing are drawn into debate on the contentious processes of official forgetting. As one young student explained:

Street art is common in Yogya and the issues [covered are] different from the daily activity of the person in the street. People in Yogya need awareness of the murders [of Munir, Udin, Marsinah and Widji Thukul] and that the government can sell our space. Street art alerts us to the issues in the public space, so everyone can see it, and everyone can learn it and get involved (Kasih)

can also be read as a warning to authorities that resistance to oppression can be readily amplified by the young. In sum, Digie Sigit’s visual call to ‘aesthetic emergency’ (Zabala Citation2017) emphasises that silence cannot be maintained. Desiring a connection with local audience is an essential part of creative practice for the Yogyakarta street artists. As Digie Sigit himself declared in interview, ‘it would be a visual violence if any street work could not be read by [the] public or it has no content about public interest’. For local people, street art is a prominent, accessible and widely affective art form that speaks to them directly about the silencing of dissent, about political corruption, and denial of human rights.

Killing and disappearance of political activists also featured in a 2014 collective street art project sponsored by the Jakarta-based human rights group Barisan Pengingat (Guards of Memory), working through a local NGO. The featured dead activists were Udin, Marsinah, Widji Thukul and Samin Surosentiko. These were large works. See .

Marsinah (1969-1993) was a worker at a watch factory in East Java during the Suharto era. Despite directions from the Governor of East Java to increase wages, the company refused. Marsinah negotiated for 500 workers who went on strike over inadequate wages and transportation. She was abducted following a demonstration, her body found four days later. No one has ever been charged for her rape and murder. She drew international attention to the Suharto dictatorship and the exploitation of workers. Speaking on behalf of the street artist collective, Digie Sigit explained that, ‘Marsinah was found dead in a wretched state. This artwork is related to her activism; at the time she and her friends were demanding their welfare rights as labourers. Although Marsinah has gone [in 1993], her spirit remains with us. This action is our solidarity with Indonesian workers’. As well as a striking black and white depiction of Marsinah herself, the 25 m-long mural () showed oppressed factory workers, and a disintegrating transport lorry. In fact, each large work in the Barisan Pengingat project bore the same headline: WHO OWNS INDONESIA? (Indonesia Punya Siapa?), and each had a crossword with clues to stimulate audience engagement. Some answers were already provided in the crossword grid. Other spaces were left blank for the public to fill in.

Another group mural in the project featured human rights activist and poet Widji Thukul ().

Widji Thukul, born in 1963, was a well-known poet whose work was often critical of the Indonesian government and the social conditions of the nation. In 1993 Thukul became affiliated with the radical left-wing People’s Democratic Party, which was outlawed by Suharto. He disappeared after a demonstration in Jakarta in 1998 and is assumed to have been killed. In the extensive Barisan Pengingat project mural, the visual image of the murdered poet was based on a familiar Widji Thukul poster by street artist AntiTank. AntiTank’s stencils are freely available for download from his website thereby evading capture by the capitalist market and State sanction. Adi, a local rickshaw driver, commented about the original poster-sized stencil of Widji Thukul, ‘when we see this work, we remember the past’. The written message in , hanya satu kata: Lawan! (There is only one word: Resist!), suggests that it takes only one voice of resistant to initiate a collective movement for solidarity and change. As street artist Bayu Widodo explained about the Widji Thukul mural, ‘it is hoped that the community can be encouraged to carry out joint movements and play a role in seeking to resolve human rights violations and fight injustice’. The symbolic bound and gaunt figures of the oppressed people of the nation imply that injustices continue in the here and now, and must be exposed.

The Barisan Pengingat street art project may be read as a collective enunciation of the minor art (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987); a subversive trope of artistic endeavour with political resonance. Painting tasks were shared between the artists, usually without individual attribution. Resistance to the conventions of mainstream fine art practice are also evident in the use of visual discourse and textual allegory to create political echoes that stretch from the past to the present and into the future. As art within the minor (subversive) canon, it ‘stops being representative to now move towards its extremities or its limits’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1986, 23) because it is constituted not in the fixed mainstream, but along the transformative plane of ‘becoming’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1994). Yogyakarta collective street art happens at a far distance from the relative safety of individual studio-based art. As one student viewer observed, ‘the artists prioritise the connection between issues and placement of murals. The artists try to make a simple correlation between site, style, and themes. I guess it’s all about making it efficient and easy for folks to understand’ (Jerry). The assemblages speak to the wong cilik, the ordinary people on the street.

It seems the political connotations of the murdered activist murals were indeed well understood. The artworks were quickly ‘vandalised’ by local gangs and by others denouncing the left-wing politics of the theme. Nevertheless, the street artists of Yogyakarta kept painting and remained committed to ensure that such stories from the past are brought into the streets for all to see. As one of the junior artists explained, the Barisan Pengingat street art project was designed to ‘rememorise, recall, and raise awareness about political conspiracy’ (Malam). Street art is a way of making historical issues resonate in the contemporary context by deterritorialising matters that have been relegated or territorialised to remain in the past. For the collective street artists of Yogyakarta, the streets constitute their platform of remembering; of reminding the local people about historic moments often forgotten or concealed. In that sense, Yogyakarta street art provides a ‘minor’ history that resonates against the ‘major’ literature of official Indonesian history discourse.

THE JOGJA ASAT PROJECT

The 2014 Jogja Asat (Yogyakarta’s Drought) street art project was launched as part of the wider Jogja Ora Didol (Yogyakarta is Not for Sale) DIY movement, which put pressure on the regional government to stop unregulated over-development in the city (see Roitman Citation2019). The word asat (drought) refers to critically low water levels in residential wells. The fall of the water table in Yogyakarta and surrounds is due to largely unregulated housing, retail and hotel development, from which local and regional politicians derive financial benefits. Street artist AntiTank explained the problem,

City residents who live around new hotels and malls experience drought in their wells in the dry season, which is the only time this has happened throughout history. In a little while, all of Yogyakarta’s water supply will experience shrinkage and our children will miss out. Our city environment will continue to experience a tremendous acceleration of damage. Jogja Asat is a warning to the Mayor, the Regional Head of District and the city government to return the mandate to its citizens.

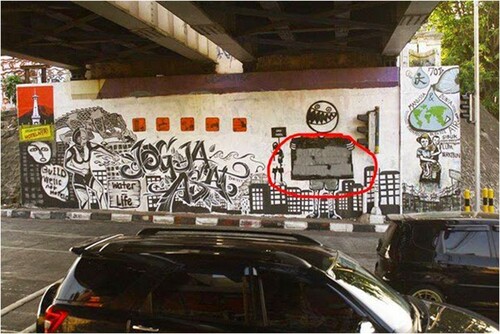

The Jogja Asat project used creativity and networking to plug disparate elements together into an assemblage of protest and awareness-raising about the water supply problem. It organised the creation of documentary films, artworks and songs to generate social criticism of the city authorities and to encourage resistance. The Jogja Asat hashtag was incorporated into some of the artistic works (Suharko Citation2020, 237). Established street artists like Digie Sigit, HereHere, Media Legal and AntiTank worked with community group Gerakan Warga Berdaya (Movement of Empowered Citizens) to create murals. The large public artworks foregrounded the fall in the urban water table and the dislocation of ordinary people’s lives by making visual depictions of the negative effects of unregulated development, lack of urban planning, political greed and population shift. For example, on the walls of the central Kewek Bridge underpass, a central location, the Jogja Asat street artists collectively created a large mural depicting the groundwater crisis through visual metaphors and gags ().

The collectively-painted work depicts the drying up of poor residents’ wells that once supplied them with water. It is a complex image with many fantastical elements, much irony, and textual additions. It is executed in black, white and red; red and white being the colours of the Indonesian flag, which implies a nationalist intent. Similar images were adapted for printing on t-shirts. A published account of the event remarks that, ‘the mural and the t-shirts were an apt media for attracting the attention of the public while also raising awareness’ (Suharko Citation2020, 238). The wide and tall underpass walls of the Kewek Bridge constitute one of the most desirable hot spots for street art expression in the city. Equally, the broad space and high visibility make the site attractive to advertisers. The street artists enthusiastically placed their joint mural there despite signage prohibiting it. It was quickly painted over. Although there had been token preventative efforts in the past, in the 2014 election year, official negative attitudes towards street art intensified when the artists began targeting the city’s burgeoning hotel development. Street artist Pribadi explained,

The civil police arrested one street artist for an infraction of a city bylaw for cleanliness. Other artists had their [Jogja Asat] artworks blocked by civil police officers and other city authorities. We got blocked really quickly by them. The city authorities must have been worried, and that makes the project a success.

Figure 7. Jogja Asat mural. Manusia & dunia air dikomposi oleh 70%, sibuk membangun lupa berkebun – Humans & the world are composed of 70% water, too much development means we forget farming (Artist: Media Legal).

Figure 8. Later Jogya Asat joint mural – Build wells not hotels. Water is life. Life is water. Protect water. No water no life. Do not cover your ears Har – Haryadi Suyuti, the Mayor (Artists: HereHere and multiple artists).

In addition, street artists sent hand-drawn postcards to Mayor Haryadi Suyuti, and to the Yogyakarta City Council, protesting against the municipal administration’s ineffectual control over rampant urban development that caused a fall in the water table.

The local and national media in 2014 reported widely on the creative protest actions of Jogja Asat, and the blocking of street artworks by local authorities. That further intensified discourse critical of the government in the arts community, in the general population and in social media. It meant the campaign was achieving a measure of success. As a local man commented on the Jogja Asat actions,

This message was powerful because I have seen it in mass media, TV and newspaper, and street art is effective because the government was disturbed by this movement and the community has discussed those issues … it’s created a conversation and spread the discourse. And when the government blocked it, it proved that street art is powerful (Kasih).

The Jogja Asat project and aftermath demonstrates how the creative imaginaries of new futures can prefigure social and political change. The project’s Facebook site remains active even today, and photos of the murals survive in that medium. That confirms the argument that digital audiences intensify and multiply the affect of street art practice by extending the reach of revolutionary projects beyond the immediate environs. Street artworks thus evade to some extent the apparatus of capture (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987) which seeks to shut down any minoritarian creative practice before it can realise its radical potential. In examining the dynamic between the collective of artists and the authorities on this occasion, we are reminded of the argument by Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1986, 18) that the ‘minor’ fills ‘the conditions of a collective enunciation that is lacking elsewhere’. ‘Illegal’ artworks produced by street artists during the Jogja Asat protest movement constitute a form of the ‘minor’ as a subversive creative enterprise on the plane of radical possibility. They point to the moral imperative for delivery of social justice and environmental redress. The street artist collective set out to challenge the hegemonic discourse of the universal benefit of progress in the city by visually provoking the critical interest of citizens passing by. Their murals and other works drew attention to the problematic impacts of urban development on the everyday lives of people in local communities.

DISCUSSION

We propose that the concept of rebel imaginings is productive for describing the Yogyakarta street artwork discussed above. First, while art is not in itself sufficient to accomplish political revolution, it may be revolutionary in principle because it hints at utopia (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1994, 100); it imagines an alternative future. Street artworks are visual expressions that critise the status quo and therefore point towards a differently configured socio-political destination. Second, we propose that the concept of rebel imaginings embraces both the artist and their art in the practice of subversive visual activism. Collectively-generated rebel imaginings in the creation of the artworks directly challenge contemporary art practices that prioritise individual talent, corrupt business practices, and government regulation and policies. The works themselves draw on past mythology, on remembered history, and on numerous elements in the immediate milieu, regardless of the artists’ chosen styles, mediums and sites. They make a direct political argument that invites agreement or disagreement, drawing the local people into debate and questioning.

Third, in a city renowned for traditional fine art and contemporary gallery showings, street art asserts the subversive nature of artistic endeavour, where collective creativity uses iconoclastic means to push for material change. As glimpsed in the examples above, the visual activism of the street artists canvassed issues of environmental degradation and political corruption. Their visual interventions did not cause anything directly, but nevertheless created an inflection towards social change. In the case of Jogja Asat, the local authorities initially pursued punitive actions. Later they moved to enact legislation that slowed development in the city. We propose that the audiences of the Yogyakarta street artworks – the passers-by – affectively engage with the political messaging of street artists’ aesthetic activism and then potentially go on to demand political and social change. Both parties can be read as ‘becoming’ revolutionary in that sense.

For Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1986) everything about the ‘minor’ is political and future-oriented. Street art as a form of subversive minor art calls its audience into being as a critical entity along the radical line of flight that foreshadows change. The ad hoc, ‘illegal’ artworks on city walls provoke flows of desire in those who view them. Subsequently, resonance between the rebel imaginings of artists and the activated rebel imaginings of the audience has potential to unsettle dominant discourses of both the State and the contemporary mainstream artworld. In theoretical terms that treat the street art of Yogyakarta as an assemblage, desire for political change and redress of past wrongs drives the creative process of becoming. The street artworks generate meaning through past and present resonances; through visual juxtapositions of ancient myths and contemporary problems and hopes. In that sense, elements of the assemblage are drawn into new territories of value and relevance which imply a different kind of future. The Yogyakarta street artworks seek to provoke radical questioning.

As a strong visual prompt, street art contributes to the materiality of political activism, yet that activism is decentred and rhizomic. Street art operates independently of the artist or artists to bring the message of their aesthetic activism to audiences regardless of whether the artist or anyone else is there to explain the work. We propose that expression of the rebellious imagination in creative practice is part of the appeal for local audiences. The rebellious imagination of the street artist acts as an agent of deterritorialisation because it prompts desire in the sense intended by Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987). That is, it offers passers-by a line of flight into further possible activism or dissent; it invites them into the radical potential of becoming; to bring about a more democratic and equitable future.

CONCLUSION

There are certain cities in the world where the visual delights and provocations of street art are on manifest display: Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Seoul – and Yogyakarta. In those cities, street art does indeed interject into the cityscape ‘like a scream’ (Baudrillard Citation2016, 99). In Yogyakarta, as elsewhere, the local street art reflects collective memories of the nation. It is exuberant, iconoclastic and political – all at once. In this article, we chose to consider that visual phenomenon using a framework suggested by the conceptual work of Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987). From that perspective, we conclude that the rebel imaginings of the street artists of Yogyakarta are articulated on the potentially transformative trajectory of becoming that inheres in contested public urban space. The visual works of street artists challenge the marginalisation of those people rendered powerless within the city by unequal economic growth, the modernisation of Indonesian society, human right violations, environmental policies, and political corruption and nepotism. Subversive imaginings are enacted and amplified in the quotidian creative practice of the street artists. It is their collective aesthetic practices and dispositions which make Yogyakarta street art a fertile provocation for thinking about change.

The assemblage of street artist collectives, the artworks themselves, the engaging audience – and the city itself – achieves multiple levels of connection rhizomically. The work of street artists calls in a non-linear way on existing historical conditions and current arrangements of power, resistance, and desire. In visual terms, the artists set out to activate shock, recognition and resonance. They employ the tactic of aesthetic rupture; a rupture that fractures the urban environment of city streets through colour, meaning and affect; through satire and deliberate play with images and words.

For many street artists, creative practice flows in a continuous stream of immanence. They never stop thinking about the politics and aesthetics of their artistic quest, talking about it, and doing it with others. Actual rewards, monetary or otherwise, are rare. Rather, their street art is a de-centred practice that constitutes ceaselessly ‘becoming’ artists in a richly rebellious sense. They are creative nomadic practitioners engaged in collaborative visual work which co-produces their rebel imaginings in the direction of imminent social and political change. In principle, street art in Yogyakarta encourages and incites other contemporary artists to produce visual pieces which are not only democratically distributed and accessible to all classes of society, but which can engender positive social action towards a more equitable future.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michelle Mansfield

Michelle Mansfield is a sociologist and Head of Domestic Programs, Pathways and Academic Support Centre, University of Newcastle, Australia. Her research interests include youth, street art, creative practices, aesthetic activism, Indonesia, widening participation at university and transitional education pedagogies.

Pam Nilan

Pam Nilan is Honorary Professor in the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation at Deakin University, and Conjoint Professor (Sociology) at the University of Newcastle. A youth sociologist, she has researched and published on youth topics in Australia, Indonesia and Fiji.

Gregorius Ragil Wibawanto

Gregorius Ragil Wibawanto is a researcher at the Department of Sociology and Youth Studies Centre, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences Universitas Gadjah Mada. He received his Master Degree in Asian and Pacific Studies from The Australian National University in 2019. Gregorius' research and engagement interests are in youth studies, contemporary art, media, and education.

References

- Arbuckle, H. L. 2000. Taring Padi and the Politics of Radical Culture in Contemporary Indonesia. Perth: Curtin University.

- Awad, S. H. 2020. “The Social Life of Images.” Visual Studies 35 (1): 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2020.1726206.

- Baudrillard, J. 2016. Symbolic Exchange and Death, translated by Iain Hamilton Grant. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Bengtsen, P. 2014. The Street Art World. Lund: Almendros do Granada Press.

- Berman, L. 1999. “The Art of Street Politics in Indonesia.” In Awas! Recent art from Indonesia, edited by T. Lindsey, and H. O'Neill, 75–77. Melbourne: Indonesian Arts Society.

- Bowen, J. R. 1986. “On the political construction of tradition: Gotong royong in Indonesia.” The Journal of Asian Studies 45 (3): 545–561. https://doi.org/10.2307/2056530.

- Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th edn. Oxford: OUP.

- Crosby, A. 2013. “Remixing Environmentalism in Blora, Central Java 2005-10.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (3): 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877912474535.

- Dahl, S. 2016. “Nongkrong and Non-productive Time in Yogyakarta’s Contemporary Arts”. Parse 4: 109-119. Accessed 9 April 2021. http://parsejournal.com/article/nongkrong-and-non-productive-time-in-yogyakartas-contemporary-arts/.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1986. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus, translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1994. What is Philosophy?, translated by Hugh Tomlinson, and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

- Geertz, C. 1990. “Popular art’ and the Javanese tradition.” Indonesia 50: 77–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/3351231.

- Geertz, C. 1998. “Deep Hanging out.” New York Review of Books 45 (16): 69–72.

- George, K. M. 2005. Politik kebudayaan di dunia seni rupa kontemporer: AD Pirous dan medan seni Indonesia [Cultural Politics in the World of Contemporary art: Ad Pirous and the Indonesian art Field]. Yogyakarta: Universitas Sanata Dharma and Cemeti Art Foundation.

- Henderson, C. 2008. “Visual Field Notes: Drawing Insights in the Yucatan.” Visual Anthropology Review 24: 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-7458.2008.00009.x.

- Heryanto, A. 2014. Identity and Pleasure: The Politics of Indonesian Screen Culture. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Ingham, S. H. 2007. Powerlines: Alternative art and Infrastructure in Indonesia in the 1990s. PhD diss. Australia: University of New South Wales.

- Irianto, A. J. 2001. “Tradition and the Socio-Political Context in Contemporary Yogyakartan art of the 1990s.” In In Outlet: Yogyakarta Within the Contemporary art Scene, edited by J. Supangkat, 53–86. Yogyakarta: Cemeti Art Foundation.

- Khasnabish, A. 2008. Zapatismo Beyond Borders: New Imaginations of Political Possibility. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Lee, D. 2013. ““Anybody can do it”: Aesthetic empowerment, urban citizenship, and the naturalization of Indonesian graffiti and street art.” City & Society 25 (3): 304–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/ciso.12024.

- Lehman-Schultz, C. 2009. “There Be Dragons.” Art Monthly Australia 220: 55–56. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.166728808432394

- MacDowall, L., and P. de Souza. 2018. “‘I’d double tap that!!’: Street art, graffiti, and Instagram research.” Media, Culture & Society 40 (1): 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717703793.

- Mansfield, M. 2020. On the Streets: Youth Street art in Yogyakarta as a Contemporary Assemblage. PhD diss. Australia: University of Newcastle.

- Martin-Iverson, S. 2014. “Bandung Lautan hardcore: Territorialisation and deterritorialisation in an Indonesian hardcore punk scene.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 15 (4): 532–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2014.972636.

- Masny, D. 2014. “Disrupting Ethnography Through Rhizoanalysis.” Qualitative Research in Education 3 (3): 345–363. https://doi.org/10.4471/qre.2014.51

- Massumi, B. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- McCormick, C., M. Schiller, S. Schiller, and E. Seno. 2015. Trespass: A History of Uncommissioned Urban art. Cologne: Taschen.

- Nashar. 2002. Nashar. Yogyakarta: Yayasan Bentang Budaya.

- Nilan, P., A. Demartoto, A. Broom, and J. Germov. 2014. “Indonesian Men’s Perceptions of Violence Against Women.” Violence Against Women 20 (7): 869–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214543383.

- O’Sullivan, S. 2010. “From Aesthetics to the Abstract Machine: Deleuze, Guattari and Contemporary art Practice.” In Deleuze and Contemporary Art, edited by S. Zepke, and S. O’Sullivan, 189–207. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Padi, Taring. 2011. Taring Padi: Seni membongkar tirani (Taring Padi: Art Smashing Tyranny). Yogyakarta: Lumbung Press.

- Pan, L. 2015. Aestheticizing Public Space: Street Visual Politics in East Asian Cities. Bristol: Intellect.

- Philipps, A., S. Zerr, and E. Herder. 2017. “The Representation of Street Art on Flickr. Studying Reception with Visual Content Analysis.” Visual Studies 32 (4): 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2017.1396193.

- Pink, S. 2013. Doing Visual Ethnography. 3rd edn. London: Sage.

- Riggle, N. 2010. “Street art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplace.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68 (2): 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6245.2010.01416.x

- Roitman, S. 2019. “Urban Activism in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Deprived and Discontented Citizens Demanding a More Just City.” In Contested Cities and Urban Activism, edited by N. M. Yip, M. A. Martínez López, and X. Sun, 147–170. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rose, G. 2012. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. 3rd edn. London: Sage.

- Roychansyah, M. S., and S. Felasari. 2017. “Is Social Media an Effective Whistleblower to Control Government Policy of Urban Development in Yogyakarta City?” Journal of Built Environment, Technology and Engineering 2: 142–150.

- St. Pierre, E.A. 2004. Deleuzian Concepts for Education: The Subject Undone. Educational Philosophy and Theory 36, 3: 283-296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2004.00068.x

- Suharko. 2020. “Urban Environmental Justice Movements in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.” Environmental Sociology 6 (3): 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2020.1778263.

- Supangkat, J. 2005. “Art and Politics in Indonesia.” In In Art and Social Change: Contemporary art in Asia and the Pacific, edited by C. Turner, 218–228. Canberra: Pandanus Books.

- Tamboukou, M. 2010. “Charting Cartographies of Resistance: Lines of Flight in Women Artists’ Narratives.” Gender and Education 22 (6): 679–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2010.519604.

- Taylor, C. 2013. “Mobile Sections and Flowing Matter in Participant-Generated Video: Exploring a Deleuzian Approach to Visual Sociology.” In Deleuze and Research Methodologies, edited by R. Coleman, and J. Ringrose, 42–60. Edinburgh.: Edinburgh University Press.

- Turner, C. 2005. “Indonesia: Art, Freedom, Human Rights and Engagement with the West.” In In Art and Social Change: Contemporary art in Asia and the Pacific, edited by C. Turner, 196–217. Canberra: Pandanus Books.

- Ulmer, J. 2017. “Writing Urban Space: Street art, Democracy, and Photographic Cartography.” Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies 17: 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708616655818.

- Walmsley, B. 2018. “Deep Hanging out in the Arts: An Anthropological Approach to Capturing Cultural Value.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 24 (2): 272–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2016.1153081.

- Walter, M. 2010. Social Research Methods. Melbourne: OUP.

- Young, A. 2016. Street art World. London: Reaktion Books.

- Zabala, S. 2017. Why Only art Can Save us: Aesthetics and the Absence of Emergency. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Zaelani, R.A. 2001. Yogyakartan art of the 1990s: A Case Study in the Development of Indonesian Contemporary art. In Outlet: Yogyakarta Within the Contemporary Indonesian art Scene, ed. M. Larner 107-152. Yogyakarta: Cemeti Art Foundation.