Abstract

In this visual essay, I draw on my own photographs taken as a so-called food-aid monitor working in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea for the United Nations World Food Programme. I provide an autoethnographic account to allow consideration of the visual dimension of humanitarian aid: everyday observations, field visits and snapshots inform humanitarian action. I intend to shed a different light on the inherent visual politics of this aid practice and, hence, build a different kind of knowledge concerning (aid assistance in) the country.

INTRODUCTION

In this visual essay, I draw on my own experiences and photographs as a so-called food-aid monitor working in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) for the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP). The visual seems to play an important role in how the outside world gets to know the DPRK, commonly referred to as North Korea. Often described as a ‘black hole’ suggesting that little knowledge about the isolated country is available, it appears that visualisations are the primary means by which to make sense of this putative enigma. Satellite images are said to give crucial information about the regime's weapons programme or its notorious prison camps. Footage and photography of North Korea's daily life purport to give glimpses of its real living conditions.

I provide an autoethnographic account to allow consideration of the visual dimension of humanitarian aid: everyday observations, field visits and snapshots inform humanitarian action. There is no doubt that humanitarian assistance has a visual dimension to it too. One can think of media representations of natural disasters, relief operations or charity advertisements (see Benthall Citation1993; Moeller Citation1999; Wright Citation2002). In all these instances, the visual is essential to mediate messages of help transmitted to public audiences (for key work on humanitarian aid see for instance Barnett and Weiss Citation2008; De Waal Citation1997; Terry Citation2002).

By foregrounding an autoethnographic perspective, I intend to shed a different light on the inherent visual politics of this aid practice and, hence, build a different kind of knowledge concerning (humanitarian action in) the country. Autoethnographic studies assume that subjective accounts and reflections of the ‘self’ are legitimate sources of scientific knowledge (see Brigg and Bleiker Citation2010; Inayatullah Citation2011; Weber Citation2011). Often providing an alternative understanding of the issues at stake, visual autoethnography can be used to reflect on the political significance of one's own experience through images. Certainly, personal experience and epiphanies are not an end in themselves, but shall matter to the extent that they ‘directly illuminate the political issues at stake’ (Bleiker Citation2019, 9).

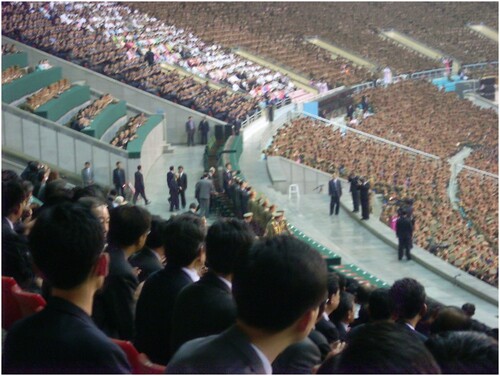

For example, my arrival in North Korea coincided with reports and rumours about the state of health of Kim Jong-il, then leader of North Korea, which began to circulate in early September 2008. The New York Times reported on 9 September that Kim was likely to have suffered a stroke and be seriously ill (Mazzetti and Sang-Hun Citation2008). I took the picture in on 10 September, the day of my arrival, during the annual Arirang Festival in Pyongyang. The iconic mass performances were given to mark the 60th anniversary of North Korea's founding.

The photograph shows the moment when the country's political and military elite entered the stadium in which the festival was taking place; state television is filming; the people in front of me have turned their heads towards the leadership. Kim, who usually attended these propaganda shows, did not show up. The blurry picture aptly reflects the geopolitical ambiguity and uncertainty that was linked to the absence of Kim from state events like this one. He had also not been seen a day earlier during a military parade. So, not seeing Kim fuelled further speculation about his health and an imminent reshuffle among the country's leadership cadre (Lankov Citation2008). In this sense, the photograph helps to ‘directly illuminate the political issues at stake’ (Bleiker Citation2019, 9), that is to reflect more closely upon the political implications of Kim's absence for domestic and international affairs.

The following section provides the background of my involvement in humanitarian aid before I visualise my experiences as a monitor of food aid.

BACKGROUND

In May 2008, the United States government announced it would provide 500,000 tons of food aid to North Korea. Earlier, UN officials and North Korea experts had warned of an imminent humanitarian crisis due to severe shortages of food. In June 2008, one of my PhD supervisors forwarded me an email from the German embassy in Pyongyang, North Korea's capital, which stated that the WFP was looking for short-term consultants for its emergency operation in the country. The job profile demanded Korean-language skills without holding South Korean citizenship – an unconditional requirement by North Korea, one I could meet. So I applied, and three months later my plane landed at Pyongyang International Airport.

All pictures were taken between September and November 2008 in the north-eastern provinces North Hamgyong and Yanggang. These provinces are (still) considered by the WFP to be most vulnerable to food insecurity. Food insecurity can be defined as the limited availability of and accessibility to food. Due to the refusal of the North Korean authorities to extend my visa, I had to leave the country by early November. I learned later that due to the politicised nature of the issue of Korean-speaking staff, the visas of all Korean speakers were not extended, meaning that they had to leave the country too eventually.

VISUALISING AID PRACTICES

Seeing and Knowing North Korea

Monitoring teams, which consisted of one driver, one national and one international staff member, had special access to the country. While other foreign visitors including diplomats, business travellers and tourists are usually only allowed to stay in the capital or to visit designated sites close by, WFP staff visited rural and remote areas of the country. In other words, the notes, observations and personal experiences of aid workers were essential for the fact-finding and decision-making processes underpinning the humanitarian operation.

For our field visits we travelled thousands of kilometres to reach affected communities. Within six weeks we had racked up more than 12,000 km of travel. Not least because of driving long distances, the WFP instructed monitoring teams to watch out for anything giving clues as to North Korea's overall economic situation. For instance, from my hotel room I could observe smoke coming from factory chimneys located in the harbour of Chongjin, the capital of North Hamgyong (). Smoking chimneys would suggest industrial activity. Furthermore, hillside cropland hints at the expansion of the overall cultivation area on the basis of acute need (see ). Regular train services and flights, which I also observed during my field trips, implied the availability of fuel. In this manner, such seeing on the micro level allowed insights and inferences on the macro level.

FIGURE 2. Smoke coming from chimneys, suggesting industrial activity; harbour of Chongjin, capital of North Hamgyong.

Important to know with regard to hillside harvest areas is that they are officially prohibited, meaning that they did not exist. North Korean officials would repeatedly deny that there was any such cropland. On my field trips I saw myriads of them, however. The existence of these areas can give insight into the level of food security of a particular region: as the need for food security grows, due to insufficient access to or availability of nourishment, so does that for cropland.

Also, hillside harvest areas contribute to soil erosion, increasing the danger of, for instance, floods. I remember that during our visit to a memorial site in Hyesan a colleague asked me to take a clandestine picture of the hillside harvest areas. Since we were forbidden to photograph ‘negative’ issues per our North Korean colleagues, we pretended to take a tourist snapshot with him in the front and the cropland in the background ().

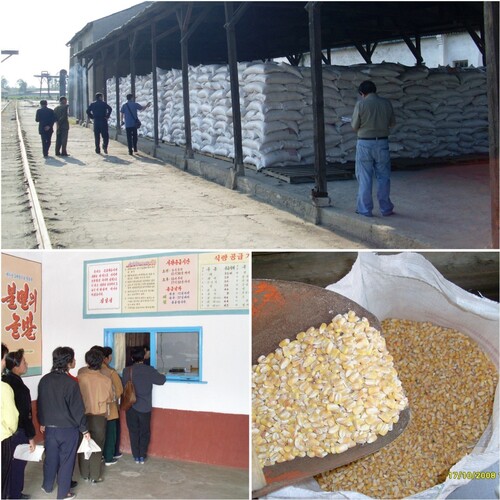

The main task of monitoring teams was to oversee and trace the allocation of food to recipient institutions, to conduct structured interviews with them and to report back to WFP HQ in Pyongyang. In the interviews, we asked aid recipients about the amount, time and type of food intake as well as about the means of preparation. We also asked households about their income and how much they spent on certain commodities such as salt and soybean paste. What I remember from the interviews is that the aid recipients asked for rice instead of the maize they were given (). The quality of the latter was poor, and I learned later that it originally was meant to feed livestock. The 500,000 tons were from a production surplus that needed to be disposed of anyways.

Donor Visibility

Food shipments arrived via ports, from where they were transported to local warehouses across the country. From there, the food was brought to so-called Public Distribution Centers (PDCs) to which individual aid recipients such as elderly and nursing women had to go in order to receive aid (see ). Other recipient institutions such as hospitals, kindergartens and orphanages were directly supplied from warehouses.

The PDCs played a central role in what is called ‘donor visibility’ in development cooperation. For the donor, donor visibility ensures that aid assistance is noticed by receiving communities. For the WFP, which needs to satisfy the donor, donor visibility ensures continuous funding and support. While there are many different forms of donor visibility (e.g. social media engagement, public advocacy, publications), in North Korea it was inscribed in the food-aid bags (). The latter featured a large US flag and an inscription, in English and Korean, saying that the food is a gift from the North American country. Thus, in our visits to the PDCs we not only checked how food aid was distributed but also whether donor visibility was properly ensured. Local officials would place empty and full bags on display so that aid recipients could readily see them.

FIGURE 5. Registration of aid recipients at a PDC during a monitoring visit; donor visibility and food receipt; food bags marked with US flag.

We were never certain whether monitoring visits were ‘real’ in the sense that we were witnessing the authentic and live distribution of food aid or whether it was just a show put on for our benefit. I remember one incident when I was about to arrive at such a PDC. I saw one man, a local official I assume, who upon realising that we had arrived started gathering and sending people to the PDC to queue for food aid, giving the impression that I was witnessing its live distribution.

Challenging and Reinforcing Vision

The ban on taking ‘negative’ pictures aptly indicates how the realm of vision is highly regulated in North Korea. There were repeated instances in which we had to discuss with our North Korean counterparts the terms under which we were allowed to take photos and make videos. In fact, I would repeatedly ask my national officer about his limits when it came to depicting North Korea, since the exact nature of what was (not) allowed was not always clear. Certainly, taking pictures of soldiers and military facilities was strictly forbidden, while photographing monuments and scenic landscapes was highly encouraged. Occasionally, I needed to show him what I had taken a picture of, while he, at times, asked me to delete a few snaps.

One way to evade the visual restrictions imposed by the North Korean authorities was to take pictures, in a semi-clandestine way, from the car as we were driving along. shows scenes from the countryside and from small towns that we passed through on the way to the east coast. Since cars – in particular, the modern, white SUVs often used in humanitarian operations – were not widespread, people would also look back at us with curiosity; something evident in the pictures below.

These images are taken from an angle, which is one of (if not) the most generic ways of depicting North Korea for outside audiences. I would sit in the back of the car taking pictures, while the national officer would sit in the front passenger seat. This angle allowed glimpses into rural and remote areas of the country: bustling street markets, beautiful landscapes, ailing infrastructure, itinerants and people who seemed not to be aware of the potential danger of fast-approaching cars (avoiding the oncoming vehicle was not on their radar).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Clara Egger for providing valuable feedback on an earlier version of my draft, Gijs de Vries for research assistance and Patrick Köllner, who, in the summer of 2008, forwarded me that email from the German embassy in Pyongyang. Special thanks go to Duilio Perez, my North Korean colleagues Mr. Ri and Mr. Kim and the WFP team in the country.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Shim

David Shim is Senior Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Groningen and visiting researcher at the Chair of International Politics and Conflict Studies of the Bundeswehr University Munich. David is interested in the visual and spatial dimensions of global politics and works at the intersection of International Relations, Geography and Area Studies. David's work on different visual media – comics, memorials, film, photography, satellite imagery, video – has contributed to the increased study of visual politics in IR. He has translated some of his research activities into teaching practice on his blog Visual Global Politics. His work has appeared, among other places, in Geoforum, International Political Sociology, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, Asian Studies Review and Review of International Studies. His book Visual Politics and North Korea is available via Routledge. LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/david-s-1a86342b/.

REFERENCES

- Barnett, Michael, and Thomas Weiss, eds. 2008. Humanitarianism in Question: Politics, Power, Ethics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Benthall, Jonathan. 1993. Disaster, Relief and the Media. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Bleiker, Roland. 2019. “Visual Autoethnography and International Security: Insights from the Korean DMZ.” European Journal of International Security 4 (3): 274–299. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2019.14.

- Brigg, Morgan, and Roland Bleiker. 2010. “Autoethnographic International Relations: Exploring the Self as a Source of Knowledge.” Review of International Studies 36 (3): 779–798. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210510000689.

- De Waal, Alex. 1997. Famine Crimes: Politics and the Disaster Relief Industry in Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Inayatullah, Naeem, ed. 2011. Autobiographical International Relations I, IR. London: Routledge.

- Mazzetti, Mark, and Choe Sang-Hun. 2008. “North Korea’s Leader Is Seriously Ill, U.S. Intelligence Officials Say.” The New York Times, September 9.

- Moeller, Susan D. 1999. Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War and Death. London: Routledge.

- Lankov, Andrei. 2008. “Who Will Lead North Korea After Kim Jong-il?” The Korea Times, July 30.

- Terry, Fiona. 2002. Condemned to Repeat? The Paradox of Humanitarian Action. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Weber, Cynthia. 2011. I Am an American: Filming the Fear of Difference. Bristol: Intellect.

- Wright, Terence. 2002. “Moving Images: The Media Representation of Refugees.” Visual Studies 17 (1): 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586022000005053.