Scientific knowledge, including in the social sciences, is about inference; laws; generalisation; explanation; causality (Stinchcombe Citation1987). First and foremost, scientific knowledge is about structure, as it relies on how we organise ideas to provide evidence, and on how we display data in a way that transmits a specific understanding of reality. But to what extent does the structuring of ideas entail the imposition of a dominant discourse? What does structuring conceal, invisibilize, make docile, or abort? By orienting our perspective(s) of the world, how much does structure ‘affect, mutilate, and generally exclude our world’ through the ‘breathless silence’ invited by the authority of well-stated knowledge (Follmann Citation2020)?

Titled ‘Against structure’, this issue is about the noise of self-organised ideas, liberatory parallels, messy connections, and unexpected emulation. It questions the methods we use, as scholars, to build a meaningful (hence legitimate) narrative out of information that would allegedly not make sense without our intervention. By doing so, the curation of this issue aims to explore ‘differant’ ways to present knowledge (Derrida Citation1972), where the definition and subsequent distinction generated by structure are made inoperative (ibid.) in order to reignite excluded meanings – in a deafening and magnificent ruckus. The curation of this issue is thus a resistance to all forms of meaningfulness that comes from institutionalised order, whose authority ‘suffocates the creative drive’ of ideas (Marcolli n.d.). For many anarchist epistemologists, modern Western science is characterised by the way it both uses knowledge as an instrument of coercion (e.g., Kropotkin Citation2018) and inhibits intellectual growth through exclusion (Feyerabend Citation2010). Therefore, what we are hoping to facilitate with this issue is a chaotic smorgasbord of ideas. Far from being disorder, chaos is the self-organised dynamics of wildness that erodes human-made structures of power. For this issue, we want your thoughts to wander, not to fit: ‘anything goes’ (Feyerabend Citation2010, op. cit.), whatever the way it goes.

By avoiding structuring manuscripts according to a theme and by favouring manuscripts that have been languishing in our archives for an unreasonably long time (2020-2022), we hope this issue invites a wide variety of interpretations and helps reflect on our journal’s short-term history of submissions (e.g., what we have received over the past three years, which manuscripts were published more slowly than others due to our curation, which effects our three-year editorship has produced on the submissions we now receive). These manuscripts span the topics of lockdown, health, refugees, conflict, entrepreneurship, identity, memory, fashion, belonging, sport, auction, semantics, parenting, labour, nostalgia, reciprocity, sexism, justice, painting, and many more. How this collection of articles, visual essays, New Media Reviews, Picture/Talks, and book reviews contributes to the field of visual studies relies only on the changing relation between what the featured authors intended and what your reading positionality generates. That is, this issue finds coherence through ‘differant’ reading(s).

A few words about the Picture/Talk in this issue: Douglas Harper, the founding editor of Visual Sociology (now Visual Studies), has used the feature as a homage to Everett Hughes, who taught him sociology. The photograph memorialises the last time that Doug saw Everett and is a tribute to Hughes’ influence on Harper’s body of work. Hughes studied under Robert Park at the University of Chicago and – along with Herbert Blumer – became one of the major figures in the rich tradition of empirical research that became known as ‘The Chicago School of Sociology’. While he never wrote a theoretical treatise, his distinctive Pragmatic approach to researching the social created a living legacy in the work of his students, to such an extent that Erving Goffman, near the end of his life, identified his own theoretical approach as ‘Hughesian’ – and he wasn’t alone. In all of his courses, Hughes required students to write a paper examining how the imaginary social world of a work of fiction was organised, and was incredulous that other sociologists wouldn’t avail themselves of the opportunity that literature – and by extension the arts – provided to explore other ‘social worlds’ and hone their analytic skills. One of Hughes’ students and closest collaborators, Howard Becker, certainly got the message and in the 1970s played a central role mobilising a younger generation of sociologists to build a ‘more visual’ sociology. It has been gratifying for his former students to witness the re-appreciation of his work that is now taking place in Canada, the United States and Europe (Grady Citation2017).

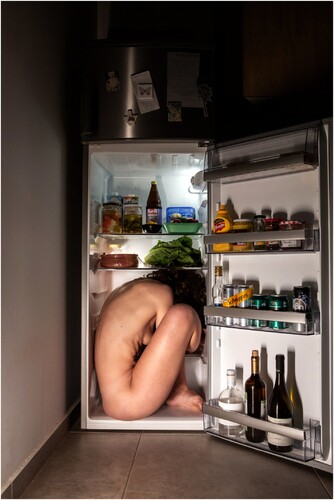

Because further structuring your thoughts runs the risk of turning this Editorial into an invitation to fit a possibly constraining frame of mind, we leave you with our cover image, by artist and scholar Sylvia Kouveli, commissioned for this issue from her personal archives.

The self-portrait series ‘Isolation Side Effects’ is a comment on belonging, and the result of the need for exploration and diversion, in the context of the restrictive measures brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. In an attempt to discover how I fit into the space within which I was confined, I began to use my own body to generate a type of somatic knowledge. I explored the concept of ‘fitting in’ as in conforming, adapting, and belonging, by attempting to literally fit my body into different sites within my living space. Beyond this overarching theme, each photo of the series touches upon sub-themes such as solitude, eating and drinking habits, escapism, and more. In this specific photo, I opened the refrigerator in search of new ways of knowing how my body relates to space. The fridge enhances the concept of preservation. In this image there is an interplay between the preservation of food and the preservation of life. During the isolation periods of the pandemic, not only did we need to preserve as much food as possible within our home in an attempt to limit contact with other people, but we also needed to preserve our lives, keeping our bodies intact and in good health. While a bare body inside a fridge alludes to the storage of corpses at a mortuary, in this image it escapes the comparison due to the position the body is in. The fetal position betrays a vulnerability, and instead of the rigidity of death it signals the malleability of new life. Through new practices and sensory experiences, sites can gain new meaning. ‘Fridge’ and the rest of the ‘Isolation Side Effects’ images reveal how the body and the self can belong in unexpected sites. While at first conforming to isolation may have been challenging, through a period of discovery and adaptation, a sense of belonging was fostered, perhaps reaching the point of seeking the security and safety of isolating oneself in absurd, solitary places such as the fridge.

References

- Derrida, Jacques. 1972. Marges de la Philosophie. Paris: Editions de Minuit.

- Feyerabend, Paul. [1975] 2010. Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge. London: Verso.

- Follmann, Clare. 2020. “Words of the Wasteland: Against a Plastic Language.” Oak Journal Audiozine 2. https://www.oakjournal.org/details/p6702105_20685233.aspx.

- Grady, John. 2017. “Review of Rick Helmes-Hayes and Marco Santoro (eds.) The Anthem Companion to Everett Hughes”, Canadian Journal of Sociology/ Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie 42(4): 451-458.

- Kropotkin, Piotr. [1913] 2018. Modern Science and Anarchy. Edinburg: AK Press.

- Marcolli, Matilde. N.D. “Science as Anarchy: Fragments of a Manifesto.” Anarcho-Transhuman 2. https://anarchotranshuman.org.

- Stinchcombe, Arthur. 1987. Constructing Social Theories. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.