Abstract

Since 1978, China has experienced an unprecedented urban and economic growth under the central government's imperative to become a global power. Whereas the central government aimed to showcase its success through ambitious infrastructure projects, distinctive skylines, and spectacular waterfronts, local officials pursued this national goal through the construction of copycats, gated communities, and theme parks and towns. From miniature Eiffel Towers and extravagant residential units to entire themed villages, local authorities and real estate developers have integrated local and global milieus as a quick-fix to upgrade the urban experience and satisfy the taste of the Chinese middle class. Despite the extensive literature in the fields of architecture, urban and social studies, the role of visual arts in the analysis of this unique urban practice has not been explored yet. Hence, this article fulfils the gap by investigating what I refer to as shanzhai (copycats) places in Mainland China through their second-hand representations in the contemporary artworks by Xiang Liqing, Zhang Peili, Hu Jieming, and Yang Yuanyuan. Through qualitative, empirical visual analysis, fieldwork and semi-structured interviews with selected artists, I explore the overlaps between visual arts and these urban phenomena to identify the dynamics and urban actors involved in space-making and suggest that private estates, copycats, and theme parks and towns do not oppose the official narrative; rather, they are localised interpretations of the national dream. Against the dominant practice of building spectacular cities, this article explores how the city could be envisioned and reproduced in the future through the selected artistic practices.

INTRODUCTION

Enclosed in a circular frame, the image of a turquoise and pink house with bizarre pinnacles and rounded balconies appears as a flashy vision seen through a crystal ball (). Privileging the unusual and one of a kind, the colourful façade blends architectural styles and cultural practices together, blurring the distinction between physical/imaginary, global/local, beautiful/ugly. This extravagant vision sparks curiosity and wonder. However, it is a popular and localised expression of China’s recent architectural practices where urban planners continuously re-assemble and re-stage cities against global and local milieus.Footnote1 This article examines this phenomenon and advances the emergence of a shanzhai city through the underexamined lens of visual arts. Specifically, I will demonstrate that the interaction between urban and artistic practices blurs the line between real and unreal, local and global, and can even hint at a new urban strategy for creating hybrid places through imagination.

This investigation will focus on four urban spaces – private estates, reproductions of international landmarks, theme parks, and themed towns – due to their popularity and overlaps with selected artistic practices. In the following section, I will analyse the creation of private estates and foreign landmarks through the artworks by Xiang Liqing (b. 1973) and Zhang Peili (b. 1957). Secondly, I will examine the photographic work by Hu Jieming (b. 1957) to articulate the process of acquiring cultural and historical capital by localising the global. Lastly, I will investigate the multimedia installation by Yang Yuanyuan (b. 1989) and suggest that cities travel across our increasingly interconnected world. The originality of this paper lies in deploying contemporary art as a critical lens to articulate the perceptions and representations of urbanisation in twenty-first-century China. Furthermore, it explores the creative practices of artists on ‘localising’ global architecture. Last, my visual analysis of selected works in response to this urban phenomenon contributes to envisioning an alternative urbanity – a shanzhai city – where the paradigms of global and local, western and eastern, real and imagined are reshuffled and overturned.

This investigation has been conducted through fieldwork, semi-structured interviews, critical theory, philosophical investigation, and qualitative visual analysis. In deploying qualitative visual analysis, I align with Jas Elsner’s interpretative description (Citation2010), an approach capable of determining the external contexts in which the artwork is produced. More than that, it is an interpretation that is intuitive and has the potential to identify some of those ‘inarticulable traces’ and ‘unintentionally captured images’ (Laughlin and Guo Citation2019, xiii), retrieving forgotten narratives and providing counter imaginaries to the dominant ones. To understand further ‘how the complexities of the sociocultural world are experienced, interpreted, and understood in a particular context and at a particular point in time’ (Bloomberg and Volpe Citation2008, 80), the notions of creativity and garden design in Chinese aesthetic tradition and ongoing conversations with artists and curators who have experienced China’s urbanisation have invaluably informed my visual interpretation. I also draw on from ethnographic methods, including fieldwork (Gready Citation2014; Kara Citation2015, 28), participant observation (Ingold Citation2014) in Beijing and Shanghai, as well as in-person semi-structured interviews with Xiang Liqing, Hu Jieming, Yang Yuanyuan and an online exchange with Zhang Peili.

Last, imagination provides the connecting thread between visual arts and the selected urban exercises. Specifically, my argument builds upon the existing scholarship in the field of social geography to conceive of the city as a socially imagined space (Lefebvre Citation1991; Soja Citation1996). Maintaining this tradition, Iain Chambers argues that today the city is also a ‘metaphysical reality’, a ‘myth, a tale, a telling’, a ‘poignant narrative’ which builds on the past, on the real and the imagined to continuously create new possibilities (Citation1990, 112). Likewise, Cinar and Bender assert that ‘the city is located and continually reproduced through such orienting acts of imagination, acts grounded in material space and social practice’ (Citation2007, xi). In other words, imagination becomes the tool to grasp the ‘complex network of interactions, negotiations, and contestation’ forming urban space (Cinar and Bender Citation2007, xxi). For this reason, as visual arts operate through imagination, in this paper I will examine selected artworks to outline some of the perceptions and speculations over China’s rapidly changing urban space. Specifically, my visual analysis will touch upon the works by Freud (Citation2003) and Lacan (Citation1973), as well as the concept of ‘imagined communities’ by Benedict Anderson (Citation1983) to tackle the unsaid and untraceable within artworks. Ultimately, I posit that visual arts amplify the practice of imagining and can depart from the dominant urban narratives and give alternative meanings to the city.

Before delving into the next section, it is necessary to define the concept of shanzhai. This term emerged in the 1980s in response to China’s globalising and modernising process after Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door and Reform Policy in 1978. Today shanzhai refers to the cheap counterfeits made in China which imitate expensive western products. Whilst this practice is widely criticised as it defies the long-established notions of creativity and originality in the west, it has made luxury and unavailable goods accessible to Chinese society, giving voice to the people (de Kloet, Fai, and Scheen Citation2019). De Kloet, Fai, and Scheen (Citation2019) argue that shanzhai involves a complex process of cultural translation, whereas Landsberger even suggests that it could be pivotal for the shift from ‘made in China’ to ‘created in China’ (Citation2019).Footnote2 Widely popular in fashion and technology, this counterfeit subculture has found a favourable ground in architecture too. Fan explains it as a natural response to a ‘mismatch between a thriving building industry and a thirsting culture, a shortcut to satisfy cultural needs’ (Citation2016, 327). As I will argue in the following section, this was certainly the case in China after the end of the Cultural Revolution as the central government urged to modernise the nation and develop cities. To describe the Shanghai Pudong, De Kloet and Scheen have already advanced the idea of a shanzhai city – a neighbourhood ‘deeply connected with and tapped into a global network of cities’ whilst being a meaningful place for its inhabitants (Citation2013, 707). Overall, the concepts of shanzhai and imagination are particularly useful in my discussion as they (1) highlight the creativity of artworks and urban practices, (2) recognise the need for a localised subculture and (3) advance alternative representations of urbanisation in 21st century China that differ from the official narrative.

PRIVATE PARADISES AND ARCHITECTURAL COPYCATS

Whereas I view the city as a socially constructed space, a concept that has proved very popular in our globalised era, especially among officials, urban planners and real estate developers is that of the metropolis as a highly concentrated site of production in the organisation of world economy (Sassen Citation1991, 29). As globalisation dramatically altered the world infrastructure and advanced a global economy that is highly united and interdependent, yet spatially dislocated, the city took up new roles (Sassen Citation1991). Specifically, it started competing in the global economy. Today, this kind of urbanity is referred to as ‘global city’ by Saskia Sassen (Citation1991) and Manuel Castells (Citation2002), whereas John Friedmann calls it ‘world city’ (Citation1986).Footnote3 Whilst the concept has been useful to articulate the economic revenue of cities, it has been widely criticised as it measures modernity according to western canons, failing to acknowledge the different contexts of the Global South.

Nevertheless, as global cities become indexical of a country’s modernity and economic role, Chinese officials promised more than forty-three global cities by the end of the 20th century (Ren Citation2011, 12). To achieve this goal and foster China’s global role, authorities and urban planners have drawn from previously successful urban models and invited internationally renowned architects to design distinctive skylines. By investing in iconic projects and memorable designs, city officials from different regions and provinces compete against each other to receive economic and political recognition whilst contributing to a peculiar urban aesthetics. Hence, these urban projects turn into highly aesthetic symbols which can visualise and promote the regional, national and international economies into a global system (Ren Citation2011; Robinson Citation2002; Sassen Citation1996).

Alongside centrally sanctioned blueprints, hybrid and extravagant urban designs have emerged at the local level in the form of life-size copycats of international landmarks, bizarre estates, and neighbourhoods reminiscent of America or Europe – shanzhai places. This bizarre phenomenon has certainly been a source of inspiration for artists like Xiang Liqing in the 2000s. Opening this chapter, Xiang’s series Residence (2006) narrates the architectural extravaganza created to meet the developing taste of the Chinese new middle class through photography.Footnote4 Each house is shot in a circular frame standing alone as if it was a portrait. Depicted frontally from a low point of view, Xiang’s photograph amplifies both the physical vicinity and perceptual remoteness which distinguishes these gated estates and their buyers. Indeed, in Residence no. 1 () the imposing gates deny both the physical and visual access to the property and suggest a sense of exclusivity. Moreover, the unusual design with turquoise-green windows and pink bricks creates a one-of-a-kind estate. Whilst Xiang aligns with China’s long-standing tradition of realism, by photographing these eclectic urban spaces, he deepens the already blurred separation between authentic and fake, urban and artistic, real and imaginary.Footnote5

What is interesting about Xiang’s photographic series is the circular frame embracing the estates, ensuring they are the undiscussed protagonists of the picture. This circular format recalls the private sight of peepshow images, ‘the physical experience of the space to dissolve into an idealised, dreamlike memory’ (Ogata Citation2002, 71). According to the artist, the circular view could allude to an impermeable bubble or the windows and gates in traditional Chinese gardens. Separating one area of the garden to the other, they stretched and intensified the sensual experience of space. Chinese writer, Shen Fu, suggested to ‘arrange the garden so that when a guest feels he has seen everything he can suddenly take a turn in the path and have a broad vista before him, or open a simple door in a pavilion only to find it leads to an entirely new garden’ (Pratt and Chiang Citation1983, 63). By looking out from the window or passing through the gate, one has the sensation of disconnecting from their own reality to enter other imaginary worlds. Likewise, Xiang’s photographs allow the viewers to momentarily detach from everyday life and delve into their fantasies, in this case flamboyant private properties.

Rather than inauthentic, as opposed to original, this hybrid architecture is the result of a complex assimilation process which can be explained by China’s specific context. Firstly, the adoption of western urban models follows years of scarce urban planning and design during the communist era as architecture was measured against functional and collective use (Bosker Citation2013). Since 1978, the dramatic socio-economic changes have urged the PRC to improve and invest in the newly emerged and divided discipline of architecture studies in China and, hence, draw from western principles and techniques (Chen and Dai Citation2014). Secondly, the re-elaboration of previously successful projects is a quick and inexpensive way to acquire engineering, architectural and technological knowledge. Ong refers to this strategy as ‘modelling’ and ‘inter-referencing’ (Ong Citation2011, 13). These two practices are simultaneously deployed in Asia, where cities take inspiration from established prototypes and measure their success against other advanced urban centres. These strategies rely on emerging Asian megalopolises, such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and Shenzhen, which can offer more localised models and solutions (Ong Citation2011, 15–18). In this context, I view the practice of integrating global and local milieus into shanzhai places as an exercise with the potential to advance new ways of placemaking and being global that resist capitalist and postcolonial approaches.

Thirdly, the recreation of western landmarks and foreign architectural styles seems to respond to the taste of a changing society (Bosker Citation2013; F. Wu Citation2004; L. Zhang Citation2010). In the last thirty years, China lifted a great number of people out of poverty. The rapid improvement of life conditions, as opposed to the previous material deprivation, has fuelled the craze for western capitalism and consumerism (Chua Citation2000; Gu and Shen Citation2003). Whereas in the pre-reform era, the four most desired durable items were the sewing machine, watch, bicycle, and radio, in the 1980s they were replaced by the television, fridge, electric fan and washing machine (C. S. Fan Citation2000). I advance that today private housing might become the new necessity to display social and economic status. Buying a high-end property allows urban residents to access a modern and cosmopolitan lifestyle and validate not only individuals’ social status, but also the nation’s economic power (C. S. Fan Citation2000, 85–87). In the words of K.S. Fan, ‘China found itself in need of exotic imageries for both cultural consumption and cultural possession, and the phenomenon of shanzhai in architecture apparently occurred at the right time, at the right place, and with the right conditions’ (Citation2016, 327).

Concurrently, real estate developers have exploited and fuelled the middle class’s fascination with the west by branding their properties with extravagant and exclusive designs.Footnote6 However, according to Bosker, it is not a simple reproduction. They carefully considered traditional customs, such as the Chinese geomantic practice, fengshui, or the need for communal areas and guest rooms to host extended families (Citation2013, 51). Their process merges foreign, appealing features with the local, historical, and cultural background of Chinese residents. By borrowing the engineering, technological, and most importantly visual and written references from the west, the housing market allows Chinese urbanites to encounter and experience California-inspired mansions, Parisian cafés and life-size reproductions of Venice within the PRC.Footnote7 Today real estate developers offer the Chinese elite and bourgeoisie a ‘private paradise’ (L. Zhang Citation2010, 2).Footnote8

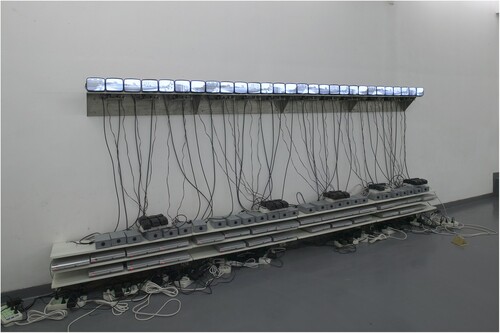

Alongside Xiang Liqing, other contemporary artists, including Qiu Zhijie and Zhang Peili, have been inspired by China’s urban shanzhai. Producing works in 2007, Qiu and Zhang photographed the US White House in Fuyang county and Venice water town in Hangzhou, respectively. On the one hand, Qiu’s documentary work, The Dream (2007), becomes extremely ironic in light of Xi Jinping’s China Dream and the recent worsening of China-US relations.Footnote9 On the other, Zhang captures one of the many reproductions of Venice around China and displays seven photographs across a row of twenty-eight small screens on the wall (Cacchione et al. Citation2017). In his video installation, A Scene in Black and White Unfolded Four Times (2007) (), the digital cityscape and individual images are repeated four times. However, such repetition is hardly visible due to the miniscule screens and intricacy of cables and devices. If this visual distraction was not enough, sensors connected to each screen blank out the image as the audience gets closer, interrupting the visitors’ sensual experience. As the seemingly comprehensive and fluid landscape continuously fades away, viewers can never fulfil their visual desire.

FIGURE 2. Zhang Peili, A Scene in Black and White Unfolded Four Times, 2007, video installation, 3.36m. Courtesy of the artist and Spurs Gallery.

Zhang’s installation is reminiscent of Michel de Certeau’s argument that ‘the desire to see the city preceded the means of satisfying it’, making the urban space unreadable (Citation1984, 92). The initial sensation of a legible, linear, and perhaps redundantly repetitive landscape is replaced by the realisation that the sight will always slip away. As the audience gets closer and more intrigued, the image disappears, leaving them dissatisfied. Like Lacan’s objet petit a, the desire to see the picture is intensified by the concomitant disappearance of the image, which oscillates between emanation and loss.Footnote10 ‘Desire manifests itself in the dream by the loss expressed in an image at the most cruel point of the object’ (Lacan Citation1973, 59). In other words, the desire for the object emerges as soon as it disappears, becoming a fantasy. As the lucidity and intensity of a vivid dream wither away and cloud the mind, likewise, the understanding of the city, especially in its twisting and bending, is similarly fragmented, and only partially satisfied in its entirety.

Furthermore, the deconstruction and reconstruction of Venice Water Town in Zhang’s work across several screens bring forth another set of ideas, modules. The notion of modularity, as oppositions merging and unifying the whole, characterises China’s philosophical tradition and can be found in the Daodejing. Compiled by several thinkers, the Daodejing (5th – 3rd century BCE) is the canonical volume that collates together eastern thought and conceives of the Dao as the generating principle. ‘Dao gives birth to one, one to two, two gives birth to three; and three gives birth to the ten-thousand phenomena’ (Laozi Citation1972). Dao is the infinite, one of the possibilities within the multiplicity, and it has a dual nature which entails both the existence and non-existence (Cheng Citation1997, 199–203). Accordingly, dualities and oppositions, instead of nullifying one another, create and ignite an incessant cycle that benefits from differences and provides the planet with the ‘ten thousand things’ (Ledderose Citation2000). The modular production at the base of the cosmos can also be found in other contexts, from painting and calligraphy to gardens, printing and even in our cities.

In the urban space portrayed by Zhang, the individual units, such as the trilobate windows or the red brick buildings in Venice, are mixed within the Chinese city to produce a completely new site. As Ledderose argues, individuality and modularity are two sides of the same coin (Citation2000, 213). There is no real or unreal, original, or fake, only an ontological unity that allows for organic, spontaneous, and fluid realities. In this ambiguous and self-referential dimension, even creativity cannot be understood as total innovation, but perhaps as a process of recombination where everything is already available around us (Cheng Citation1997, 249–254; Robinet Citation1991, 14). This notion of creativity is rooted in both east Asian thought and postmodernism. Jameson suggests that ‘paradoxically, the historic originality of postmodernism lies in the renunciation of the new or the novum’ (Citation1991, 104). Rather than unprecedented novelty, repetition becomes the standard to measure creativity. Therefore, what is often criticised for being a copy, is much more complex than that.

Overall, re-staging foreign landmarks and architecture can be interpreted as a pragmatic and economically convenient practice which develops through the feedback loop between the middle-class and real estate developers. As China’s bourgeoisies validates its social status by purchasing exotic villas and modern flats, it simultaneously substantiates the housing industry’s success and, to a wider extent, China’s economic growth. Last, I propose that this urban exercise offers an alternative approach to placemaking. In a similar fashion to shanzhai, it exploits the symbolic value of global landmarks and the success of previous engineering and architectural models to provide Chinese citizens the sense of comfort and modernisation that has long been associated with the west. Overall, the lifestyle that in the late 20th century was still a dream has become today’s unchallenged reality for a small minority, and a promise of a better future for the working class.

THEMED PARKS AND TOWNS

In this section, I lay the foundation for the end of the article by hypothesising that branding has strayed from private estates and foreign landmarks to pervade theme parks and, more widely, the urban space. Booming after World War II, the modern theme park was designed as an entertaining tool targeting the middle class (Clavé Citation2007, 16). It branded space to satisfy the imagination and sensual expectations of visitors and choreographed their whole experience through architecture (Klingmann Citation2010, 72–75; Young Citation2002, 1–2). Today, the quintessential prototype is Disneyland, which opened in 1955 (Clavé Citation2007, 1; Klingmann Citation2010, 70–75). Disneyland develops through the ‘drama of architecture’, it ‘embodies the very structure of myth, employing fables and fairy tales’ and, hence, ‘captures our imagination’ (Klingmann Citation2010, 70, 72). For instance, the combination of miniature size, soft and circular buildings, as well as the paths and speed at which different environments are experienced guide the visitors and spark evocative feelings in them. However, theme parks, as accurately designed stages and rehearsed performances, become too tightly choreographed to encourage active imagining (Klingmann Citation2010), inviting the consumption of space instead.

In China, one of the earliest theme parks is Splendid China Folk Village, built in Shenzhen in 1989 (W. Zhang and Shan Citation2016). Since the 1990s, as the construction of theme parks increased, especially around the developing area of the Pearl River Delta (Clavé Citation2007), a growing scholarship on this phenomenon has emerged.Footnote11 Amongst scholars, Li and Zhu (Citation2003) argue that theme parks in the PRC feature elements of traditional culture to boost national identity, contrary to the escapism offered by their western counterpart.Footnote12 Moreover, these magical kingdoms seem to have a common predecessor in the European and traditional Chinese gardens (Young Citation2002). Firstly, both places are separated from the outside by gates, which simultaneously provide isolation and access (Young Citation2002). Secondly, as mentioned earlier, the visitors’ sensual experience is choreographed through paths, embracing viewpoints and artificially staged architectural settings which direct the bodily and visual exploration. Thirdly, Chinese traditional gardens and themes park both function in the interstices between real and imagined, where time and space are undefined.

Indeed, according to China’s tradition, by entering a garden, looking out from the window, or passing through a gate, one would experience the sensation of leaving the physical reality to enter other imaginary worlds. Discussing the notion of ‘borrowed scenery’ (jiejing) by Chinese garden designer, Ji Cheng (1579–1642), Kuitert advances that the landscape lends itself to the viewer to induce a multisensorial experience, which ‘brings forth sensory and imaginative factors’ (Kuitert Citation2015).Footnote13 Likewise, the landscape design of theme parks allows visitors to momentarily detach from everyday life and access exclusive realms and fantasies through their suggestive views. Overall, the theme park spatialises memories and desires and can be viewed as the ‘complex result of modernization by demonstrating progress in urbanisation. At the same time, it also serves as a representation of postmodernism by contributing to the confusion between the arts and the everyday life’ (W. Zhang and Shan Citation2016).

On top of the ability to immerse visitors into carefully orchestrated fictions, theme parks align with the PRC’s goals of economic growth and national unity. Firstly, they provide economic revenue by cooperating with the housing industry and urban planners. This should not come as a surprise as some of the most popular parks are in Shenzhen, China’s first Special Economic Zone and a global hub for innovation and technologies. Secondly, several parks, such as Splendid China Folk Village, reproduce attractive scenes of China’s landmarks and ethnic minorities to promote China’s long-standing culture. Theme parks tend to objectify and reduce the diversity and symbolic depth of these sites and communities to a rehearsed and consumable experience.Footnote14 By praising the regional and national culture and celebrating the global circulation of places, theme parks attract visitors and investments to the city whilst satisfying national and economic ends (Zhong et al. Citation2014).

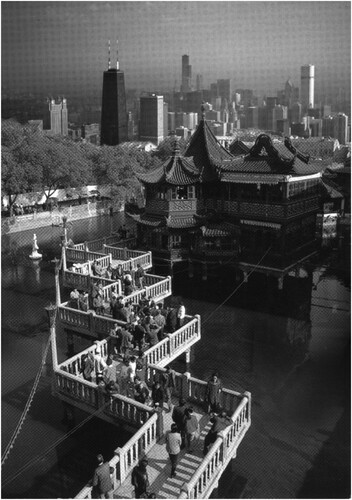

The hyper reality of theme parks is particularly significant when juxtaposed to digitally manipulated and speculative artworks. Together, they deepen and confuse the audience’s perceptual experiences adding a further layer of imagination. The photographic series Postcards (2001–2004) ( and ) by Shanghai artist, Hu Jieming, responds to this warped understanding of space by composing even more disorientating photographs. His images merge different spaces and temporal dimensions into a single picture. In Postcard #8 (), the photograph is dominated by the sight of a colourful pyramid. Like a mirage, the pyramidic structure unexpectedly replaces Beijing’s Temple of Heaven. Although at first Hu’s images appear as ordinary urban sights, at closer inspection, they reveal their hybrid and fictional character.

FIGURE 3. Hu Jieming, Postcard #8, 2001–2004, photograph, variable dimensions. Courtesy of the artist.

FIGURE 4. Hu Jieming, Postcard #5, 2001–2004, photograph, variable dimension. Courtesy of the artist.

Mostly portrayed from above, Hu’s pictures perpetuate the sensation of an exclusive scenery that only a privileged viewer could observe and control. In Postcard #5 (), Hu inserts the skyline of Chicago as the background of the reconstructed Ming dynasty Yu Garden in Shanghai.Footnote15 With the focal point slightly higher than the centre of the image, the eye follows the zigzagging of the white bridge until it reaches the sight of the first skyscrapers and more distant high-rises. Maintaining the concept of jiejing, the cityscape is integrated within the vision of the garden through a skilful artifice that fosters a sense of continuity between the two realities. This fluidity is exacerbated further by an exaggerated aerial perspective, which ‘gives the sublime sensation of bewildering height, orderly crowds and endless display of things’ (Ogata Citation2002, 72–73).

However, I argue that this overarching vision is incomplete and only satisfies the powerful urban actors. Drawing from Benedict Anderson’s research on ‘imagined communities’ and Edward Said’s study of ‘Orientalism’, this all-knowing view can be metaphorically compared to that of the coloniser, who flattens and uniforms the heterogeneity of the colony into a cohesive whole. As you zoom out to get an overview of the territory, the picture loses its definition and becomes more imaginative (Anderson Citation1983). The result is the production of ‘imaginative geographies’, which ‘is a distribution of geopolitical awareness into aesthetics, scholarly, economic, sociological, historical and philological texts. […] It has more to do with the west than the Orient’ (Said Citation1977). Said views Orientalism as a myth which reduces the knowledge of the ‘Other’ to something easily imagined and dominated by colonisers. Extending this concept to China’s urban planning, it is possible to suggest that the approximate assemblage of global and local milieus can have a significant meaning. Rather than a subjugated ‘Other’, today China wants to present itself as a strong global power which is capable of internalising and merging differences into a new cohesive order.

Hu’s collage prompts a further reflection on how places are associated with certain meanings and can assume regained significance once they are extrapolated from their original context. In Postcard #8, he combines pyramids with Beijing’s Temple of Heaven. Pyramids were originally built as tombs to extend the power and authority of the living pharaoh to the afterlife. While their construction involved slavery, the result of this immense human effort has certainly gained historical significance. Specifically, in the 1920s–30s, China experienced a craze for ancient Egypt, probably related to the excavation of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922 (Schaefer Citation2017, 124). Schaefer argues that whilst Egypt:

presented China with the fearful image of an ancient civilisation that had died out and been completely colonised. It also presented a spectacle of seeing one’s own past circulate the world and return in the form of simulacra and images. (Citation2017, 125)

Recontextualised in the analysis of contemporary shanzhai places, Hu’s photos become extremely relevant. His artistic practice shows that the operation of merging different elements into something anew is simultaneously temporal and spatial. In Postcard #7, as the Tiger Hill pagoda fluidly mutates, twirls, and grows into an unstable construction, Hu collates places from different times and geographies and recontextualises them in the contemporary urban space. Rather than imaginary and unrealistic processes, his images become possibilities, if not a foreshadowing. They neither criticise nor praise China’s urban design and aesthetics; however, they play with the ambiguity of the everchanging urban terrain. Like the choreographed spaces of the theme parks which lead visitors into walking past life-size reproductions of pyramids, Niagara Waterfalls and New York’s skyline, Hu’s photographs direct mental wandering (you) through his visual composition.Footnote17

Today, I argue that the hyper-reality of the theme park extends beyond its gates and trespasses onto the urban terrain, stretching and encompassing themed towns. The construction of themed towns in China is part of a long-established strategy aimed at decentralisation and urban renewal (Fang and Yu Citation2016). In this sense, they are reminiscent of the New Town Movement in the UK (Howard Citation1902) and the regeneration of old neighbourhoods in the US in the second half of the 20th century (Lin Citation2012). However, whereas the US and UK conceived of new towns as further extensions of the city, intensifying the opposition between urban and periphery, China views them as alternative clusters that can attract investments to the wider region (Bonino et al. Citation2019). Alongside providing solutions to overpopulation or underdeveloped areas, China’s themed towns are foremost economic and branding engines. They are part of a national plan to build twenty cities each year from 2001 to 2020 and reach a high level of urbanisation (Wakeman Citation2016, 304–305). I maintain that they integrate global and local traits to achieve three goals: showcase a hybrid cultural and national identity; comply with residents’ taste; and deploy the latest technological innovations (Lin Citation2012). In other words, themed towns are economic and branding tools that display China’s successful developments with a strong focus on globalisation.

Launched in 2001 by the Shanghai government, One City, Nine Towns is an exemplary project. With the intention to ring the metropolis with nine satellite towns, it aimed to redistribute the highly concentrated Chinese population around the outskirts of Shanghai (Zheng Citation2010, 4). Each community was designed as a replica of a foreign city: the town of Anting is based on the road structure of Weimer, Germany, whereas Thames Town in Songjiang is designed after Shakespeare’s hometown, Stratford upon Avon, including pubs, fish & chips, and red telephone booths. As the housing market profits from the evocative and attractive lifestyle it can provide, developers feed in and develop further cultural references to attract Chinese buyers (F. Wu Citation2004, 231). However, the project One City Nine Towns has failed to meet its original goals and produced, instead, unliveable towns. Unaffordable housing, high living costs, inefficient infrastructure, and lack of public transports suggest the aesthetic and economic priority over logistics. Driven by profit, most developments target the wealthier social classes, who invest in them without necessarily inhabiting them (Xue, Wang, and Tsai Citation2013).Footnote18 Moreover, Xue and Zhou (Citation2007) suggest that the satellite towns around Shanghai could be read as top-down strategies to endow the metropolis with the historical and cultural depth attached to Europe.

LOCALISING GLOBAL ARCHITECTURE

From miniature Eiffel Towers to entire theme parks and towns, the construction of replica and the adoption of western designs have proved very popular in China. Not only do they amplify the sensual experience of the urban landscape, but they visualise some of the ways in which China has integrated historically rich landmarks and successful architectural models into its territory. To an extent, this urban practice is a more localised (shanzhai) expression of the official vision for a modern and strong China. Whereas China’s national success is generally measured against distinctive waterfronts, skylines and infrastructure projects, a more creative and hidden potentiality can be found in the synthesis of local and global milieus. This synthesising practice can provide new ways of making urban space. Moreover, by producing urbanities that can travel the world thanks to their hybrid architecture, Chinese urban dwellers can acquire instant cultural and historical capital. Maintaining the traditional Chinese notions of modules and creativity, I argue that this shanzhai city continuously reinvents itself and offers new understandings of urban placemaking by ways of reassembling.

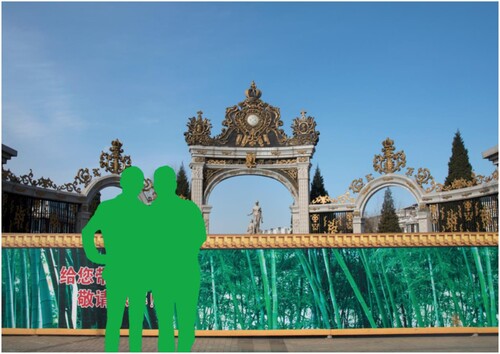

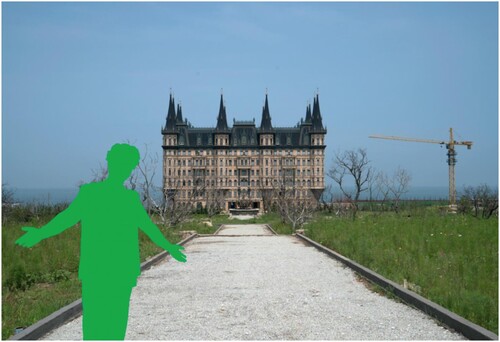

Beijing based artist, Yang Yuanyuan, refers to these hybrid spaces as constructed realities: they are mentally imagined, but often concretely assembled and absorbed within Chinese urbanities. Her multimedia work, Blue Window, Two Roses (2016) ( and ), is inspired by the overlaps between authentic/fake, real/unreal, physical/imaginary as observed in China’s urban space and departs from the popular experience of photo studios. Since the early 2000s, Yang has photographed uncanny urban spaces, including abandoned theme parks, unfinished mansions, and ongoing construction sites, among others. Part of her own archive, these pictures are particularly revealing of the width of Chinese urban practices and aesthetics. They are loaded with symbolic meaning and particularly insightful of the social, cultural, and urban transformations. Yang’s work enrichens the already dense urban experience by travelling to unexplored imaginaries and raising doubts over the physical existence of those landscapes. Specifically, her work weaves individuals’ imaginings with her own vision, forging ‘resplendent yet unreal’ ‘constructed realities’.Footnote19

FIGURE 5. Yang Yuanyuan, Ideal Life #10, 2016, archival pigment print (with frame), 41 × 61 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

FIGURE 6. Yang Yuanyuan, Living in Trending Ancient Castle, Being Leaders of the City #3, 2016, archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist.

Firstly, I argue that the range of places that Yang selects from different parts of the material and fantastic world allows her cohesive collage works to swing from the realm of imagination to physical reality, back and forth. Whereas some pictures display very recognisable landmarks, such as the Arc de Triomphe in Paris or the Leaning Tower of Pisa, other sceneries are familiar, yet ambiguous. Images of castles () and mansions reminiscent of Wes Anderson’s films, Dracula or fairy tales strike the viewers with their extravagant architectural styles. There is something enigmatic about these sights, such as the presence of yellow cranes or an overall dismissed and unfinished look, which leaves the viewers wondering whether the represented places are real or unreal. Yang’s assemblages are reminiscent of Freud’s concept of the uncanny in that ‘the boundary between fantasy and reality is blurred’ and ‘we are faced with the reality of something that we have until now considered imaginary’ (Citation[1919] 2003, 15). According to Freud, the uncanny is that sensation that arises when the ‘same situations, things and events’ reoccur (Citation[1919] 2003, 10–11). Maintaining this, Yang’s collage are fragments of familiar urban scenes drawn from shared imaginaries and representations of places which circulate more widely thanks to globalisation.

This ambiguity is amplified further as Yang photographs both her physical surroundings and the visual content of real estate billboards. Billboards, as advertising material, provide a carefully designed vision of space which has not been materialised yet while further complicating the ontological divergence between real and unreal. By deploying this evocative, visual tool for advertising, Yang interweaves an imaginary process into another to forge a third and even more layered representation. The original place becomes irrelevant compared to its reimagined site. Blue Window, Two Roses reproduces both tangible and intangible places which are nevertheless no less authentic or perceived as real by the audience. Specifically, when discussing real estate billboards, Mirra adds that they can even self-realise their own predictions. To demonstrate that, Mirra (Citation2020) draws from Jens Beckert’s concept of imagined futures. Beckert argues that ‘when decisions are made by relevant actors and are coherent with the present, hence plausible, they have the potential to shape the future and self-realise their own predictions’ (Citation2013, 15–16; Citation2016, 11). Hence, billboards, as the visualisations of the economically powerful housing market targeting China’s changing society, can potentially achieve their own visions.

Whilst Beckert’s theory is significantly limited by the denial of urban consumers’ individual agency, Yang’s assemblages reflect on ordinary citizens’ dreams by elaborating the popular practice of green screen photo studios in China. These photo studios are shops where individuals, friends, couples, and families are photoshopped against a variety of backgrounds at a cheap cost. They offer clients the possibility to transcend the physical reality and dive into a selection of imaginary scenarios, which subtend their yearnings for a certain lifestyle. The over one thousand backgrounds include tourists’ attraction sites, celebrities, cartoon characters, as well as luxurious villas and European scenes. The final photograph, as the physical documentation of such imaginary exploration, whether real or unreal, has a symbolic value. It validates the ephemeral experience and offers immediate gratification despite the spatial or temporal boundaries. Cheaper and faster than buying a high-end property or travelling to Europe, such activity provides a shortcut to acquire cultural and historical capital. Maintaining Bourdieu’s theories around class and taste (Citation1984, Citation1996), these photographic experiences at green studios make up for a lifestyle that is not available to everyone. The instantaneous experience of taking a photograph produces a flat, plastic, and momentary image, which nevertheless turns into an eternal and fluid memory loaded with emotional perceptions.

However, contrary to the green screen studio where customers would be standing against a green background to be later photoshopped and transported somewhere else, Yang blanks and replaces the figures with impersonal green silhouettes. As vacant bodies, the green silhouettes are deprived of any recognisable features and seem to invite the viewers to fulfil that emptiness. The figures are homogenous, their bodies fusing into one, and their identities amalgamating into the collective. ‘It could be you and me, he or she, all of us’.Footnote20 Furthermore, the reversal of the photoshop process hints at some changes in the dynamic and fluid circulation of space. In Yang’s photos, rather than people travelling places, it is the background that changes. As Boris Groys argues, today ‘cities are no longer waiting for the arrival of the tourist – they too are starting to join global circulation, to reproduce themselves on a world scale and to expand in all directions’ (Citation2008, 105). In other words, the city itself starts travelling places on its own through the global circulation of urban images. As a storyteller, Yang interweaves visual, verbal, and spatial language to create an immersive sensual experience which mirrors the continuous and fluid oscillation between real and unreal, physical and digital, original and fake.

CONCLUSION

While Groys (Citation2008) proposes a city that travels through the global circulation of its second-hand and digital representations, on a more literal level, some places in urban China have started offering a similar international experience through shanzhai places. This is the case of the reproduction of international landmarks, gated communities, as well as theme parks and towns analysed throughout this paper. Whilst these are circumscribed practices which do not yet embrace the whole city, they allow for a total experience of the world, physically, sensually, and culturally. They are shanzhai places in that they provide a more localised expression of architecture and urban planning which targets as well as fulfils the dreams of China’s middle class. As several people in China still cannot afford travelling to Europe and North America, these sites recreate and offer a global experience that fulfils urban dwellers’ expectations. Moreover, this emulation allows new urban spaces to acquire the cultural and historical capital that China’s changing society aims to possess and be associated with. Overall, this shanzhai city stems from the imagination and creativity of both real estate developers and local officials, on the one hand, and the Chinese middle class, on the other, producing alternative understandings of urban space.

It must be recognised that today the phenomenon of architectural mimicry and assimilation has lost its initial momentum, especially after Xi Jinping came into power in 2012. Since then, the central and local governments have been more reluctant towards foreign influences. They have promoted the uniqueness of Chinese culture (Creemers Citation2014) and condemned the postmodern and hyper-reality of Chinese cities. For instance, in 2019, the central government banned the use of exotic names for domestic buildings and laid out a list of strange and foreign names to be changed (Z. Fan Citation2019). Moreover, in 2020, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China (MOHURD) published a decree to stop the construction of architectural copycats and ‘super tall buildings’ (Citation2020). Likewise, counterfeit practices have been discouraged by the government as they breach international law and regulations (Yang Citation2015, 14).Footnote21 Since Xi Jinping, the central government and CCP have been more proactive in opposing shanzhai architecture, as part of a more widespread ideological turn that is driven by the desire to strengthen China’s national identity. However, it should be noted that these shanzhai architecture and urban exercises have the potential to be more unique than the increasingly standardised urban landscape needed for countries to compete in the global economy. As de Kloet and Scheen argue, this shanzhai city ‘is an ordinary city, a distinctive and unique place: for those who live in them, they are special and particularly meaningful places’ (Citation2013, 707). Overall, the shanzhai city – and more widely shanzhai culture – provide alternative narratives to the official one which are more tightly interlinked with society.

Indeed, the artistic works by Xiang Liqing, Zhang Peili, Hu Jieming and Yang Yuanyuan demonstrate the creativity, hybridity and evolution of Chinese architecture and urban planning, which absorb stimuli from the outside whilst being able to keep site-specific characteristics. Moreover, their works demonstrate that while urban planners and real estate developers cannot wholly depart from top-down blueprints, they nevertheless tap into the dreams and imaginaries of the local population. Specifically, artists’ practices help shift the attention from the economic revenue of urban branding to flamboyant urban features and the desires of China’s changing society in the twenty first century. Last, visual arts can provide the lens to speculate about a unique way of making space which departs from the west and blurs the line between local and global, real and unreal, original and fake, physical and digital.

GLOSSARY CHINESE NAMES

GLOSSARY CHINESE TERMS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank the artists mentioned in the article for their time and kindness, as well as my PhD supervisors, Prof Joshua Jiang and Dr Theo Reeves-Evison, for their valuable feedback. This work was developed thanks to the support and funding by Midlands3Cities/AHRC Doctoral Studentship Award.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Federica Mirra

Federica Mirra is a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow, currently leading a three-year-project titled “The City as Art: Living aesthetics in twenty-first-century China” at the Centre for Chinese Visual Arts (CCVA), Birmingham City University (BCU). She completed her PhD “Urban Imaginaries: Contemporary Art and Urban Transformations in China since 2001” at BCU, supported by the Midlands3Cities AHRC Doctoral Studentship Award. She has been published in the Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art and the Journal of Visual Art Practice and she presented at several international conferences. She worked as Research Felllow at St. Gallen University, Switzerland (2021-22), as well as Curatorial Assistant for Thailand Biennale 2018-19, and Research Assistant in the HE and art sector.

Notes

1 With milieu I refer to the architectural and design features specific to a certain culture and society.

2 Interestingly, the central government has promoted the campaign From Made in China to Created in China since 2001, when the PRC joined the World Trade Organization. For an extensive study on shanzhai and its cultural impact through the lens of nation branding and globalisation in China, see Yang (Citation2015).

3 Whilst their theories present differences, they agree that cities play a central role in today’s organisation of the world economy.

4 Author’s in-person interview with Xiang Liqing, artist’s studio, 9 May 2019, together with artist Bi Rongrong.

5 Today, documentary works diverge from the traditions of socialist and revolutionary realism which were typical of Chinese literature and visual arts in the 20th century in that they often avoid politics.

6 This is partly explained by the highly competitive housing market which pushes developers to create memorable and evocative designs.

7 Evocative names are often appointed to gated communities or hotels to make the cultural reference even more explicit. During my fieldwork in Beijing and Shanghai in 2019, I noted down the following: Oriental Hawaii, Hawaii Estate, Alpen Hotel, or Buckingham Palace.

8 With visual and written language, I refer, respectively, to the western architectural styles and the adoption of foreign and exotic places to name buildings, streets, and gated communities.

9 Fuyang White House costed more than three million yuan. It was approved by Zhang Zhi’an, former Party secretary of Yingquan district, who was nicknamed the ‘White House boss’ and later sentenced to death due to bribery and corruption charges (Tang et al. Citation2021, 1344; Tian Citation2010). Moreover, in the photographic project Appearance – Roman Pillar (2001), Qiu Zhijie depicted classical architectural elements found in China.

10 Objet petit a literally means the ‘small object a’, where ‘a’ stands for autre (other). It is the link between the real and the symbolic, a desire that can never be expressed.

11 See W. Zhang and Shan (Citation2016), Clavé (Citation2007), Young (Citation2002), Mittermeier (Citation2021), and Li and Zhu (Citation2003).

12 The practice of promoting national identities through theme parks belongs to what Michael Billig refers to as ‘banal nationalism’ – a nationalism that is diffused in everyday life and not benign (Citation1995, 6). It is worth adding that his study focuses on western nations.

13 Around 1631, Ji compiled The Craft of Gardens (Yuanye), a manual for garden design, whose final chapter was entitled after and dedicated to the concept of ‘borrowed scenery’ (jiejing).

14 See Lee (Citation2019) for a discussion on the official display of China’s culture and ethnic minorities in theme parks.

15 Author’s in-person interview with Hu Jieming, artist’s studio, 17 May 2019.

16 As the birth site for the PRC in 1494, the square has a strong political dimension and has determined the urban layout of Beijing since the Maoist era (Wu Citation2005, 7–9). Since 1989, Tiananmen Square is a highly contested site (Wu Citation2005, 9; Zhu and Kwok Citation1997).

17 You is the ability of the painter to make the viewer feel like they are immersed in the landscape without having left their room (Guo, cited in Ortiz Citation1999, 7).

18 This is the case of Thames Town, which was designed by British architectural company, WS Atkins, to supposedly host around 10,000 residents. However, around the time of its completion, it was almost deserted. Though in 2014, Henriot and Minost (Citation2017) registered more than 2300 inhabitants, the project was not nearly as successful as it should have been.

19 Author’s online interview with the artist on Zoom, 27 May 2020.

20 Author’s online interview with the artist on Zoom, 27 May 2020.

21 Yang (Citation2015) provides a complex study on shanhzai and the cultural impact of intellectual property rights regulations in China.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Beckert, Jens. 2013. “Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations in the Economy.” Theory & Society 42: 219–240.

- Beckert, Jens. 2016. Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations and Capitalist Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: SAGE Publications.

- Bloomberg, Linda Dale and Marie Volpe. 2008. Presenting Methodology and Research Approach. London and New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

- Bonino, Michele, Francesca Governa, Maria Paola Repellino, and Angelo Sampieri. 2019. “Questioning New Towns.” In The City After Chinese New Towns: Spaces and Imaginaries from Contemporary Urban China, edited by Michele Bonino, Francesca Governa, Maria Paola Repellino, and Angelo Sampieri, 12–21. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Bosker, Bianca. 2013. Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press and Hong Kong University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. “The Economy of Practice.” In Distinction, translated by Richard Nice, 93–108. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. 8th ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cacchione, Orianna, Pi Li, Robyn Farrell, and Katherine Grube. 2017. Zhang Peili: Record. Repeat. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago.

- Castells, Manuel. 2002. “Local and Global: Cities in the Network Society.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 93 (5): 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00225.

- Certeau, Michel de. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Chambers, Ian. 1990. Border Dialogues: Journeys in Postmodernity. London: Routledge Revivals.

- Chen, Bochong, and Zhikang Dai. 2014. “Reflection on Highrise-Based City Mode.” In Lofty Mountains and Dancing Waters: A Probe into the City for Tomorrow, 24–35. Germany: Alte Brücke Verlag.

- Cheng, Anne. 1997. Storia Del Pensiero Cinese. Edited by Amina Crisma. 2000th ed. Torino: Einaudi.

- Chua, Beng-Huat. 2000. “Consuming Asians: Ideas and Issues.” In Consumption in Asia: Lifestyle and Identity, 1–34. London: Routledge.

- Cinar, Alev, and Thomas Bender. 2007. “Introduction.” In Urban Imaginaries: Locating the Modern City, xi–xxiii. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Clavé, Salvador. 2007. The Global Theme Park Industry. Wallingford: CABI.

- Creemers, Rogier. 2014. “Xi Jinping’s Talks at the Beijing Forum on Literature and Art.” China Copyright and Media. 2014. https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2014/10/16/xi-jinpings-talks-at-the-beijing-forum-on-literature-and-art/.

- Elsner, Jas. 2010. “Art History as Ekphrasis.” Association of Art Historian 33 (1): 10–27.

- Fan, Chengze Simon. 2000. “Economic Development and the Changing Patterns of Consumption in Urban China.” In Consuming Asians: Ideas and Issues, edited by Beng-Huat Chua, 82–96. London: Routledge.

- Fan, Zimeng. 2019. “Diming Guanli Gongzuo Buji Lianxi Huiyi 2019 Nian Di Yi Ci Quantihuiyi Zai Jing Zhaokai” [The Department of Place Names Convenes for the first time together in Beijing in 2019]. Minzhengbu Wangzhan [Ministry of Civil Affairs]. 2019. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-04/03/content_5379240.htm.

- Fan, Kerry Sizheng. 2016. “Shanzhai.” Architecture and Culture 4 (2): 323–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/20507828.2016.1177707.

- Fang, Chuanglin, and Danlin Yu. 2016. China’s New Urbanization: Developments Paths, Blueprints and Patterns. Beijing: Springer Geography.

- Freud, Sigmund. [1919] 2003. Border Dialogues: Journeys in Postmodernity. London: Penguin Books.

- Freud, Sigmund. 2003. The Uncanny. Edited by David McLintock and Hugh Haughton. London: Penguin Books.

- Friedmann, John. 1986. “The World City Hypothesis.” Development and Change 17:69–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.1986.tb00231.x.

- Gready, Paul. 2014. “First Encounters: Early Career Researchers and Fieldwork.” Journal of Human Rights Practice 6 (2): 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huu013.

- Groys, Boris. 2008. “The City in the Age of Touristic Reproduction.” In Art Power, 101–108. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gu, Chaolin, and Jianafa Shen. 2003. “Transformation of Urban Socio-Spatial Structure in Socialist Market Economies: The Case of Beijing.” Habitat International 27 (1): 107–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(02)00038-3.

- Henriot, Carine, and Martin. Minost. 2017. “Thames Town, an English Cliché.” China Perspectives 1:76–89.

- Howard, Ebezener. 1902. Garden City of To-Morrow. Edited by F. J. Osborn. London: Faber and Faber.

- Ingold, Tim. 2014. “That’s Enough about Ethnography!.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4 (1): 383–95. https://doi.org/10.14318/hau4.1.021.

- Jameson, Fredric. 1991. Postmodernism: Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Edited by Stanley Fish and Fredric Jameson. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Kara, Helen. 2015. Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Klingmann, Anna. 2010. Brandscapes: Architecture in the Experience Economy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- de Kloet, Jeroen, Chow Yiu Fai, and Lena Scheen. 2013. “Pudong: The Shanzhai Global City.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (6): 692–709.

- de Kloet, Jeroen, Chow Yiu Fai, and Lena Scheen. 2019. “Introduction: We Must Create?” In Boredom, Shanzhai and Digitisation in the Time of Creative China, edited by Jeroen de Kloet, Chow Yiu Fai, and Lena Scheen, 13–37. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Kuitert, Wybe. 2015. “Borrowing Scenery and the Landscape That Lends - The Final Chapter of Yuanye.” Journal of Landscape Architecture 10 (2): 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2015.1058570.

- Lacan, Jacques. 1973. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis. London: Karnac.

- Landsberger, Stefan. 2019. “Shanzhai = Creativity, Creativity = Shanzhai.” In Boredom, Shanzhai, and Digitisation in the Time of Creative China, edited by Jeroen de Kloet, Chow Yiu Fai, and Lena Scheen, 217–24. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Laozi. 1972. Daodejing. New York: Vintage Books.

- Laughlin, Charles, and Li Guo. 2019. “Reportage and Its Contemporary Variations: An Introduction.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 31 (2): x–xvi.

- Ledderose, Lothar. 2000. “Introduction.” In Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art, 9–24. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lee, Juheon. 2019. “Promoting Majority Culture and Excluding External Ethnic Influences: China’s Strategy for the UNESCO ‘Intangible’ Cultural Heritage List.” Social Identities 26 (1): 61–76.

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Li, Ying-li, and Feng Zhu. 2003. “Huaqiaocheng Kechixufazhan Zhuti Xingxiang Lilun Yanjiu” [A theoretical study on the sustainable development of the image of OCT]. Renwen Dili 18 (10–3): 15–18.

- Lin, Zhongjie. 2012. “Building Utopias: China’s Emerging New Town Movement.” In The Emerging Asian City: Concomitant Urbanities and Urbanisms, edited by Vinayak Bharne, 225–33. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Mirra, Federica. 2020. “The Art of Billboards in Urbanized China.” Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 7 (2–3): 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1386/jcca_00030_1.

- Mittermeier, Sabrina. 2021. A Cultural History of the Disneyland Theme Parks: Middle Class Kingdoms. Bristol: Intellect.

- MOHURD (Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the PRC). 2020. “Zhufang He Chengxiang Jianshebu Guojia Fazhan Gaige Wei Guanyu Jin Yi Bu Jiaqiang Chengshi Yu Jianzhu Fengmao Guanli de Tongzhi” [MOHURD and the National Development and Reform commission issue a notice on strengthening further the management of cities and]. MOHURD. 2020. http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/jzjnykj/202004/t20200429_245239.html.

- Ogata, Amy F. 2002. “Design History Society Viewing Souvenirs: Peepshows and the International Expositions Author.” Journal of Design History 15 (2): 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/15.2.69.

- Ong, Aihwa. 2011. “Introduction: Worlding Cities, or the Art of Being Global.” In Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global, edited by Aihwa Ong and Ananya Roy, 1–24. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing.

- Ortiz, Valérie Malenfer. 1999. Dreaming the Southern Song Landscape: The Power of Illusion in Chinese Painting. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Pratt, Leonard, and Su-Hui Chiang. 1983. Six Records of a Floating Life. London: Penguin Books.

- Ren, Xuefei. 2011. “Space, Capital, and Global Cities: An Introduction.” In Building Globalization: Transnational Architecture Production in Urban China, 1–18. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Robinet, Isabelle. 1991. Histoire Du Taoisme Des Origines Au XIV Siècle. Paris: Cerf.

- Robinson, Jennifer. 2002. “Global and World Cities: A View from off the Map.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26 (3): 531–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00397.

- Said, Edward. 1977. Orientalism. London: Penguin.

- Sassen, Saskia. 1991. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. 2001st ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sassen, Saskia. 1996. “A New Geography of Centers and Margins: Summary and Implications from ‘Cities in a World Economy’.” In The City Reader, edited by Richard Legates and Frederic Stout, 70–74. London: Routledge.

- Schaefer, William. 2017. Shadow Modernism: Photography, Writing, and Space in Shanghai, 1925–1937. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Soja, Edward. 1996. Thirdspace: journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Tang, Zhuxin, Xinyuan Wang, Xumeng Zhang, Bingbing Hu, Yunyi Wang, and Jie Li. 2021. “The Influence of Culture Value of Civil Engineering Projects on Their Life-Span.” In Proceedings of the 23rd International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, edited by Fenjie Long, Sheng Zheng, Yuzhe Wu, Gangying Yang, and Yan Yang, 1325–1346. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Tian, Lan. 2010. “Death Sentence for ‘White House Boss.’” China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2010-02/09/content_9447216.htm.

- Wakeman, Rosemary. 2016. Practicing Utopia: An Intellectual History of the New Town Movement. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Wu, Fulong. 2004. “Transplanting Cityscapes: The Use of Imagined Globalization in Housing Commodification in Beijing.” Area 36 (3): 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0004-0894.2004.00219.x.

- Wu, Hung. 2005. Remaking Beijing: Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space. London: Reaktion Books.

- Xue, Charlie Q. L., Ying Wang, and Luther Tsai. 2013. “Building New Towns in China - A Case Study of Zhengdong New District.” Cities 30 (1): 223–232.

- Xue, Charlie Q. L., and Minghao Zhou. 2007. “Importation and Adaptation: Building ‘one City and Nine Towns’ in Shanghai: A Case Study of Vittorio Gregotti’s Plan of Pujiang Town.” Urban Design International 12 (1): 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000180.

- Yang, Fan. 2015. Faked in China: Nation Branding, Counterfeit Culture, and Globalization. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Young, Terence. 2002. “Grounding the Myth: Theme Park Landscapes in an Era of Commerce and Nationalism.” In Theme Park Landscapes: Antecedents and Variations, edited by Terence Young and Robert Riley, 1–11. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks.

- Zhang, Li. 2010. In Search of Paradise: Middle-Class Living in a Chinese Metropolis. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

- Zhang, Wen, and Shilian Shan. 2016. “The Theme Park Industry in China: A Research Review.” Cogent Social Sciences 2 (1): 1–17.

- Zheng, Shilin. 2010. “Preface: Visions on the Urban Development of Shangai.” In Shanghai New Towns: Searching for Community and Identity in a Sprawling Metropolis, edited by Harry den Hartog, 4–6. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

- Zhong, Shien, Jie Zhang, Hao Luo, and Honglei Zhang. 2014. “Variations on a Theme Park in Contemporary China.” Asia Pacific World 5 (2): 101–22. https://doi.org/10.3167/apw.2014.050208.

- Zhu, Zixuan, and Reginald Yin-Wang Kwok. 1997. “Beijing: The Expression of National Political Ideology.” In Culture and the City in East Asia, edited by Won Bae Kim, Mike Douglass, Sang-Chuel Choe, and Kong Chong Ho, 125–150. Oxford: Clarendon.