Abstract

Protests are, and have always been, fundamentally visual and embodied phenomena. However, the unprecedented quest for visibility instigated by social media brings about novel intricacies for contemporary political action. This article explores the function of bodies as tools of visibility in performative protests that develop throughout immediate and mediated levels of visuality. Through a methodological strategy combining snap-along ethnography and coordinated comparative fieldwork, we analyse two Extinction Rebellion protests – in Finland and Portugal – as they move from the street to the internet. We argue that, more than mere bodily public disruptions using the online sphere for representational purposes, these are ritualised forms of protest that, through the offline-online conjunction, construct the bodies as sites of imagination: in the streets, bodies work as enactors of ritualised performances; on social media, bodies become tools of visual dissonance and cultural prefiguration. Using the concept of ritual as an analytical lens facilitates an understanding of how international protest repertoires are locally embodied and how bodies are visually re-signified, including the recreation of the spectators-protestors’ dialectic to evoke imagined worlds. By shedding light on how bodies are visually transformed through ritualised offline-online performances, this article contributes to understanding how radical climate movements articulate political claims that appear to break away from conventional modes of argumentation.

INTRODUCTION

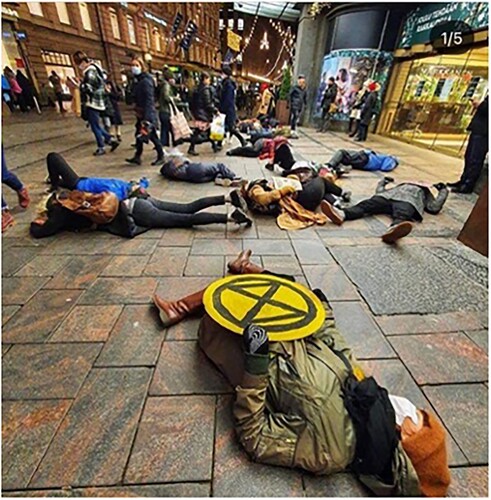

The activists fall onto the pavement in a coordinated composition in front of the department store. Across the street, numerous people stop and stare at the bodies that are now lying silently and immobile, blocking most parts of the store entrance.

(Fieldnote, November 27th 2020, Finland)

The blood-stained, masked bodies of the activists move across the street following a choreography designed to create an impression of the red-robed bodies dissolving into one collective non-human body: slow steps and gestures, all bodies moved as one, with empty eyes and neutral facial expressions as if they were in another existential plane.

(Fieldnote, November 27th 2020, Portugal)

Street protests, from the earliest bread riots to today’s theatrically staged protest performances, are essentially embodied. The threatening, legitimising, or moving presence of bodies forms the core of this type of political action. Protests have always brought bodies to the fore – hungry bodies, angry bodies, suffering bodies, determined bodies. Likewise, visibility has always been the prerequisite for a protest to count as protest: a bread riot hidden in the woods is as difficult to conceive of as political action as a street demonstration no-body [sic] sees. Still, the reliance of today’s activism on social media – with the production and circulation of protest images being fundamental in the visibility quest (Faulkner Citation2020) – brings about novel intricacies for contemporary political action (McGarry et al. Citation2020). First, an increasing emphasis on the afterlife of the protest extends its effect beyond its immediate temporality. The visual dimension of protest then becomes ‘not just a matter of the immediate spatial and temporal context of protest, but also of how photographs are used to mediate and extend this context’ (Faulkner Citation2020, 166–167). Second, activists have gained increased power over the definition, framing and depiction of their protest images, although this necessitates a struggle with the algorithmic logics of social media (e.g. Barassi Citation2015), which makes the production of catchy and memorable imagery instrumental. Considering that ‘researchers do not yet comprehend the contemporary potentials of visual culture and digital media in affecting social change’ (McGarry et al. Citation2020, 19), this article paves the way for an analytical engagement with the ways in which visuality is forged in the intertwinement of offline-online contexts.

Recent studies on XR have focused on the regenerative culture of the movement (Sauerborn Citation2021), the movement’s leaderless organisation (Fotaki and Foroughi Citation2022) and its nonviolent direct action as ‘image events’ (Weaver Citation2022; see also DeLuca Citation2021). While these studies suggest the transnational and strategic emphasis on directing public imaginations towards alternative ways of seeing the world, they largely bypass the question of how this is produced via embodied protests that unfold chiefly at the intersection of offline and online action. A Red Rebel Brigade and a Die-In are the two forms of protest analysed in this article, as well as several similar precedents in other contexts. By methodologically combining offline and online ethnographic observations (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022), we use the two simultaneous XR protests as grounds to analyse the development of embodied performative protest actions as ritualised forms of protest, exploring the role of bodies at both immediate and mediated levels of visuality.

In our analysis, we identify the key elements at play in these visualised, embodied protest performances, and ask, what kinds of interpretations of current contentious politics can be made therefrom. We suggest that bodies function as enactors of ritualised protest performance on the street and of visual dissonance and cultural prefiguration on social media. On the street, bodies primarily assume the instrumental role of bringing rituals to life; it is when the ritual becomes mediated that bodies gain new roles as tools of dissonance and prefiguration, laying the foundation for narratives of certain imagined futures that must be either avoided (mass extinction, as represented in the die-in action) or built (cultural regeneration, as symbolised by the Red Rebel BrigadeFootnote1).

The following section articulates, considering the increasing role of online visuality, the literature on performance and ritual in social movements. Then we describe our methodological strategy: snap-along ethnography and coordinated comparative fieldwork. Next, we ethnographically describe the immediate spatial and temporal context of protest: how were the protests carried out in public spaces? What roles do bodies and visuality play in the protests’ practices? We then turn to the mediated dimension of the protest and explore the online visual content that was produced. Drawing analytical depth from the concept of ritual, we reflect on the development of embodied protest performances as the protest moves from the street to the online sphere.

BODIES AND RITUALS IN PERFORMATIVE OFFLINE-ONLINE PROTESTS

As stated by Mattoni and Teune (Citation2014, 876), social movements and protests are in essence visual phenomena, and it is bodies that often figure as the key tools of visibility, expanded through mediatised images of embodied protests (Gonzalez Citation2022; McGarry et al. Citation2020). Even though such embodiment of protest has always been subject to both immediate and mediated or postponed visibility, it is the current form of (social) media society that has furthered this feature in political protests.

In analysing the Occupy movements, Judith Butler drew on Arendt’s notion of the street as a ‘space of appearance’ to discuss the assembly of bodies in public space as a political act (Butler Citation2011). Exposed to the gaze of others, ‘the body has its invariably public dimension […] constituted as a social phenomenon in the public sphere’ (Butler Citation2004, 21). Indeed, the body as ‘a citizen’s most basic element in the expression of protest’ (Doerr and Teune Citation2012, 49) has served diverse functions in different types of protest. In early bread riots and their offspring, bodies were a direct threat of power reversal; in mass demonstrations, bodies function as proof of support and determination for the cause; in protest performances involving fewer bodies, they invite the viewer to feel compassion, shock or outrage, as in the examples of actions that this article is focused on, as well as in many predecessors in the history of die-ins, public hunger strikes, sit-ins and the like (e.g. Del Gandio Citation2015; Feola Citation2018). Common to all of these options is that bodies are inherently a tool – and sometimes the only tool – of a protest’s visibility.

Feminist scholars’ contributions to the concept of performativity have laid the groundwork for understanding how bodily performances create the world (not only describe it) and make normative ideals and social constructions playable (not only reproduced; e.g. Baer Citation2016; Butler Citation2004, Citation2015). Performance is, of course, not the property of social movements alone. However, these movements often use it as a strategic and tactical tool ‘to communicate with a larger public and to produce oppositional discourses’ (Juris Citation2015, 228). In response to this use, Hohle (Citation2010) suggested the concept of ‘embodied performances’ to encompass current social movements’ forms of symbolic communication, which challenge civic norms and promote cultural and political change. Feminist media studies, particularly the scholarship of cyberfeminism and transnational digital feminism, call attention to the need to grasp the complicated relationship between the analogue and the digital in embodied and performative processes (e.g. Baer Citation2016; Bhatia Citation2022; Coffey and Kanai Citation2023; Gonzalez Citation2022; Greene Citation2021; Liinason Citation2023). The traditional conception of online environments as producers of disembodiment serves as a backdrop to studies exploring how feminist bodies are constructed in the online visuality (Baer Citation2016). Research shows how images serve purposes of embodiment (Gonzalez Citation2022), promote transnational visual grammars of feminist performances (Liinason Citation2023) and transgress gender binaries (Greene Citation2021). However, as noted by Gonzalez (Citation2022), research tends to approach online visuality as a representational arena – a space to depict the diverse ways in which the physical body can become a site of resistance. Scholars in this field have been questioning the significance of the vulnerability-resistance binary in understanding the body-offline-online (Bhatia Citation2022), arguing for the need to conceptualise the body as a ‘porous boundary’ (Butler Citation2004, 25) that emerges at the juxtaposition of digital and street spaces (Baer Citation2016; Coffey and Kanai Citation2023). Our study takes this argument seriously: by going beyond the visual representation of bodies and their communicative functions in the online sphere, we empirically account for the offline-online simultaneity within which bodies are visually constructed through ritualised processes.

In sociology, the use of the concept of ritual to understand collective political action is not new (e.g. Casquete Citation2003; Hurd Citation2014; Rothenbuhler Citation1988; Szerszynski Citation2002). Casquete (Citation2003, 8) defined protest rituals as ‘all the regularly occurring symbolic performances staged by social movements in the public sphere with the manifest purpose of influencing both the authorities and public opinion’. Moreover, rituals can play a key role in symbolically loading performances: conveying meanings, re-signifying places and creating new identities (Hurd Citation2014). However, the concept of ritual has been applied to collective action mostly as a generator of inward effects, such as group solidarity (Casquete Citation2003), forms of communication (Gordon Citation1956) and collective identity (Hurd Citation2014). Importantly, it has been suggested that ritualistic performances have the potential to create what Turner (Citation1982) called a ‘liminoid’ space, where the gap between ‘indicative’ (how things are) and ‘subjunctive’ (how things ought to be) closes. Analysing protests as rituals enables the identification of other features, including the repetitive and symbolically loaded dramatisation of scenes (Doherty Citation2000) and the emphasis on visuality and embodied ‘communicative action’ that disavows discursive-based argumentations (Szerszynski Citation2002). Szerszynski (ibid.) explored different strategies of ritualisation in environmental movements, drawing on cases from the UK in the 1990s. Inspired by these analyses, we take cues from three characteristics. First, we emphasise visuality, physical embodiment and connotation. In our cases, the focus is on the performances unfolding both on the street and in the images, both of which are treated as forms of argumentation and claim-making. Secondly, the protest performances comprise a narrative played out following a certain script. Thirdly, and perhaps most strikingly, protests can be seen to use ‘forms of action that are in some sense charged, marked-out from life as normal’ (Szerszynski Citation2022, 55). They introduce a disruptive vision to everyday life: the die-in invites the audience to visit a future of mass extinction, whereas the Red Rebel Brigade provokes the audience to imagine an alternative (regenerative) future.

Following the growing importance of the visual realm in the social sciences (Doerr and Teune Citation2012; Mitchell Citation1994), the production of images as collective meaning-making should be seen as a political process (Rogoff Citation1998). Once they can ‘speak about things that are not immediately visible’ (McGarry et al. Citation2020, 24), images may hold particular value concerning climate mobilisation, in which ‘the problem is one of imagination rather than of representation’ (Schneider and Nocke Citation2014, 12). Recent studies show the multifaceted effects of images, for instance, in producing alternative framings of protest events (Neumayer and Rossi Citation2018), arousing emotional engagement (Kharroub and Bas Citation2016) and mobilising uninvolved citizens (Jasper and Poulsen Citation1995). Furthermore, the development of visual frame analysis (Luhtakallio Citation2012, Citation2013) and the conceptualisation of visual orders (Clément and Luhtakallio Citation2021; Seppänen Citation2006) have brought the power struggles around images to the fore.

The potential of an image as a tool of protest is enhanced when the cause of the protest is visually dramatised, such as in images that ‘deploy a dystopian and negative aesthetics and [which] stage interventions in the public sphere’ (Fasnacht Citation2021, 225). McGarry et al. (Citation2020, 26) argue that the ‘aesthetics of protest render distinctions between digital and material spaces negligible’, which reinforces the need to grasp not only the offline and online dimensions but also the interconnections between them. Despite critiques of social media’s promotion of individualistic expression (e.g. Milan Citation2015), research has also shown how activist groups can appropriate social media logics in favour of political change (e.g. Treré Citation2019) and strategically compromise with the algorithm’s demands while shielding their civic values and articulating their political voices (e.g. Malafaia and Meriluoto Citation2022). This article contributes to this body of literature by analysing XR’s performances as ritualised forms of protest in the constantly fluctuating offline-online space.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The first two authors have been involved in Extinction Rebellion activities as part of ethnographic fieldwork in Portugal and Finland, respectively, in the framework of a large comparative project concerning visual politics in current activism. The methodological grounds of the analysis lie in the method of snap-along ethnography developed for the project to provide tools for studying the simultaneous, intertwining offline and online aspects of today’s visual political action (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022). The method takes inspiration from walk-along (O’Neill and Roberts Citation2020) or go-along (Kusenbach Citation2003) ethnographyFootnote2, observing peoples’ everyday experiences as they move through their habitual routine. However, the ‘walk-along’ and ‘go-along’ methods are limited to the corporeal, street and immediate levels; they fall short of grasping contemporary political action. The snap-along tackles the offline-online concomitance in shaping today’s visual-based modes of action, as the researcher follows participants as they snap, post and comment on images. This method follows participants across multiple online and offline communities to better understand how digital and analogue forms of engagement are mutually constitutive: picture-taking and picture-using are followed in their everyday life settings, while the ‘life online’ is followed simultaneously and with equal intensity (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022).

This article is furthermore based on a coordinated field study made possible by the long-term collaboration of the authors. Harnessed through a comparative study design of a joint research project, the first two authors simultaneously carried out fieldwork on XR protest actions. After discussing their findings and comparing their notes, they formed a micro-comparative design to analyse two relatively similar cases with a shared theoretical optic. This comparative strategy directs attention to features, both converging and differing, that unfold their particularities once exposed to a parallel case (Luhtakallio and Tavory Citation2018; see also Lammert and Sarkowsky Citation2010; Lamont and Thévenot Citation2000; Luhtakallio Citation2012).

To operationalise the theory-driven comparison, the first two authors co-coordinated observation of a particular protest event occurring simultaneously in both countries: the Black Friday sales in November 2020 – probably the busiest shopping day of the year and a symbol par excellence of modern consumerism and its undue costs for the environment and workers’ conditions. The actions were likely the two best-known and most eye-catching performances by Extinction Rebellion worldwide: the Red Rebel Brigade (Portugal) and the die-in protest (Finland). Both protests took place in large metropolitan areas. Compared to previous actions, the turnout was relatively low due to COVID-related constraints. Still, approximately 30 activists participated in the die-in and more than 15 in the Red Brigade’s protest. In both countries, the protestors’ profile is analogous: mostly white, female activists aged 18–35. The majority were either studying at university or in precarious transition situations – dropping out or seeking a job. The ethnographers’ positions in the field were facilitated by both being young adult women – in their early 30s and late 20s; the former had prior ethnographic experience with social movements. Being in a similar age range with the participants and aligned about environmental concerns were important aspects in the process of rapport building that was developed over several months of fieldwork. Throughout the ethnography, informed consents were signed by key participants in the movement. We produced the material for this analysis through the snap-along ethnographic steps (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022): having earlier established relationships with the respective groups, we observed the nearby preparations and the actual events on site while simultaneously following how the events unfolded online. We examined these actions with the aim of understanding their shared characteristics.

By combining ethnographic participant observations with the analysis of protest images and videos published online, this study touches upon the immediate and mediated aspects of the aesthetics of protest – spheres that, while analytically separate, are experienced together (Faulkner Citation2020; McGarry et al. Citation2020). Following the intertwined nature of these dimensions (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022), the analysis addresses the question of ‘the visibility of protest [as] both a matter of direct visual experience and of images’ (Faulkner Citation2020, 158). As we tried to sort the different material objects depicted and shared online (see Doerr and Teune Citation2012), it became clear that what was visible on the street and online were first and foremost the bodies. Indeed, in the Finnish case, only an XR hourglass logo was included in the images posted online – held by a ‘non-alive’ body lying silently on the pavement. In Portugal, while posters held by activists showcased important messages (e.g. ‘This is an emergency’), the slow-motion dystopic bodies of the Red Rebel Brigade were at the centre of the visuals. Therefore, to examine how these protests transform the role of bodies as tools of visibility at both the immediate and the mediated levels, we analyse these protests using the concept of ritual (Casquete Citation2003; Szerszynski Citation2022).

THE IMMEDIATE UNFOLDING OF PROTESTS: BODIES ENACTING RITUAL PERFORMANCES

Although the protests were organised by local groups, they followed a standardised, replicable format. The Finnish XR decided on a die-in action, ‘a peaceful, non-violent protest wherein participants lie on the ground for a specified amount of time: a solemn act that symbolises the kind of future we face without government action on the climate crisis’.Footnote3 The Portuguese XR put together a Red Rebel Brigade, embodying ‘who the people have forgotten to be’, and thus symbolising ‘the common blood we share with all species that unifies us and makes us one’.Footnote4 Combining our ethnographic observations, we explore how these protest performances followed standardised, repetitive and premeditated rules, thus creating ritualistic actions (Szerszynski Citation2002). We describe the immediate development of the actions, showcase how the rituals came to life in local activist groups, and explicate how bodies played a key role in the process.

In Finland, the die-in was planned less than a week before the action took place. This was not the first time that the Finnish XR had performed a die-in, but the organisers were nervous. The following fieldnote excerpt describes the beginning of the action and its motivations:

On our way there [to the city centre], the group splits into a few smaller ones in order to better blend in with the people on the street. Carita,Footnote5 one of the organisers, has a big bag of accessories, signs and a megaphone with her, and she asks whether I could help her carry them. As we walk, I ask her what she thinks is the motive for this action. She talks about the contradiction between the die-in and consumption and how the goal of the action is to make people realise the link between consumption, overproduction and biodiversity loss; how everything is connected. The idea of lying down in the middle of the street, in the middle of all the people and their Christmas shopping spirit, makes her nervous, but she concludes rather calmly that the die-in is easy to implement since it has been done before and thus is considered a ‘workable concept’. (…) The fact that the die-in has reportedly been implemented in shopping malls before was mentioned by other activists as bringing confidence. Moreover, in their view, the die-in fits well into the context of the Block Friday action: the critique of capitalism.

In Portugal, it was the first time that the activist group had put together a Red Brigade. During a period marked by figuring out how to cope with the pandemic-related downplay of climate issues, the group decided that introducing an innovative tactic would both increase public visibility of the climate emergency and energise the members. Since the group had no previous experience with this action, following the guidelines of the international movement to reproduce the Red Rebel Brigade – the red dresses, white painted faces, and choreography, in which the activists resemble human statues gently moving across the street – was demanding. The next fieldnote excerpt describes the preparatory moments of the protest. The bodily transformations acquired a central role, alongside the collective arrangements for producing online visual content.

During the previous week, several videos related to the Brigade (about the style of movements typical of the Brigade, how to rehearse, the steps for making the costumes, etc.) had been shared in the WhatsApp group created for the purpose of organising this action.

On the action’s day, I stood still while Elsa wrapped the cloths around me, then she went to get the makeup and spread the white paint over the face and painted the eyes and eyebrows with a heavy black, following the video tutorials that were being shown in a loop on the laptop. Meanwhile, one of the activists was circulating among us with a camera, recording these preparatory moments (…) When we looked at each other, and at ourselves, in the mirror, we were all amazed. ‘We hardly recognised each other!’ said one of the activists. Ecstatic satisfaction arose in the room and mixed with a certain adrenaline rush, as we were all about to go out to the street.

- ‘When I saw those red cloths on the floor, they seemed to have no shape, I thought about the fiasco that this was going to be. I didn’t want to say it out loud. I tell you now because this is fantastic!’ Miguel said.

- ‘I can’t believe this is really going to happen!’ Elsa exclaimed with visible excitement.

(…) During the preparation of the action, some members talked about XR’s international workshop on regenerative culture, stressing ‘how we need to reinvent ourselves: how we relate to others and to the world’, said Xavier.

As soon as the action began, numerous passers-by dug out their cameras and started filming the event. Many simply stopped and remained standing in place while staring at the ‘bodies’ lying silently and immobile, blocking most parts of the entrance to the department store. This blocking was completed by some of the passers-by who, instead of walking through the ‘bodies’ on the ground, stopped in front of the entrance to follow the action and to film it or take pictures (…). Some spectators look impressed, even happy and admirative, although many scarcely react: they just walk in and out of the doors as if nothing is happening. Nobody expresses irritation, except a woman who complains: ‘I just might have enough space to go through here’. Some reactions are humorous, like a young man who, leaving the department store while stepping over the ‘bodies’, notes to his companion, ‘I guess these must be some kind of feminists’ before disappearing into the crowd.

The people on the street watched closely, looking surprised and standing still when the Brigade was passing by (…). The Brigade’s most repeated movement was one with arms raised wide, palms facing the sky and the arms slowly rising towards the sky. When the Brigade was stopped, a block formation was adopted, oscillating between the victory movement (closed fists and right arm moving slowly towards the sky as a symbol of revolution and solidarity) and the position of love (the arms come together towards the chest and the head slowly lowers) (…). Meanwhile, the group’s leading photographers were recording the procession (…). A lot of people passing by stopped for several minutes observing the Brigade and taking pictures with their cell phones (…). In the shopping centre, the Brigade continued through the food court for several minutes due to some perplexity on the part of the security guards, clearly confused as to how to interact with the performers.(…) When we were on the street again, the police arrived, addressing the leading person, Elsa. The conversation with the police lasted about 30 min. For the Brigade – securing the ‘performative mode’ – it felt like 2 h. I came to know later that the police wanted to identify Elsa but that after all the other activists wanted to be identified as well, and also after people passing by had intervened, saying that nothing wrong was being done, the police officers ended up giving up.

In the street, their bodies functioned as tools of spectacle, playing a crucial role as enactors of the ritualised performances. In both countries, the set of bodies ‘interrupting’ daily life was crucial in making the actions visible and at the same time provocative enough to compel the passers-by to stop, watch and photograph. Not only were they key tools of the protest’s visibility, but they also served as strategic instruments for creating distance from and strangeness for the spectators – a ritualistic formula that, while drawing public attention, seemed to prevent antagonistic reactions from the audience. Our ethnographic observations report curiosity, perplexity, interest and admiration – such that the passers-by themselves either unintentionally helped to complete the blocking in Finland or actively talked the police out of action in Portugal. Since the audience was not facing typical protesting bodies but rather bodies setting an intriguing and harmless tableau, this format allowed ‘the public to witness protest on a different register … [the protestors] are received as a performance troupe before they are seen as protestors’ (Coombs Citation2020, 128). As a result, passers-by became spectators (Adut Citation2018, 28).

The ethnographic accounts of the protests’ development in the street shed light on their visual and performative dimensions: on the one hand, bodies were purposefully staged as visual artifacts (the [re]actions of picture-taking from the public and the activists); on the other hand, the bodies stood in the way of interaction (the theatrical composition of the red-robed/dying bodies and its instrumental role in neutralising negative reactions from both the audience and the police). The separation between the performers and the audience (Juris Citation2015), based on a degree of repetition (Benford and Hunt Citation1992), highlighted the ritualistic features of these protests. Following Szerszynski’s conceptualisation (Citation2002, 54), these protests were ‘executed with a heightened sense of being for display, to be especially attended to by participants and observers’. Furthermore, as pointed out by Butler (Citation2011), material environments are also important parts of protest action, and indeed, movements often enact protest rituals at places and times that they believe contain or communicate a symbolic meaning (Casquete Citation2003, 10). Both protests took place at the entrance of a popular shopping centre in the downtown shopping district during Black Friday sales, which have quickly become a symbol of current (excesses of) consumption. The spatial and temporal aspects play a crucial part in the events by bringing the performing bodies into the very heart of consumerist buzz – interrupting it. The protesting bodies react either by succumbing to the overconsumption and climate crisis (in the Finnish case) or by regenerating through adoption of a new way of living (in the Portuguese case). As will be shown in the next section, these are key elements of the claims the activists made, although they may not be apparent to passers-by in the street. We next analyse the mediated protest: what changes when the ritualised embodied protests are mediated?

THE MEDIATED UNFOLDING OF PROTESTS: BODIES PERFORMING UTOPIAN AND DYSTOPIAN FUTURES

Both protest groups used social media to mediate their protest performances and extend their immediate temporality. In Portugal, it was decided not to send any press releases to the mainstream media, a visibility that carried the risk of disempowering effects. The temporality between the immediate context of protest and its public online appearance was characterised by strategic management of the public online content. Over the following days, publications referring to the action began to appear. These aimed to create a sense of suspense (e.g. images in a poster-type layout with half of a Red Rebel’s face), and the captions included a countdown for the release of a video of the action. These choices seemed to be paving the way to non-material engagement with the protest aesthetic, blurring the divide between material and digital spaces as arenas of political agency (McGarry et al. Citation2020). The video of the Portuguese activist group was released a week after the protest. As in Portugal, there was no previous social media coverage of the action in Finland. However, almost immediately after the action, the local Finnish XR posted a series of pictures on its Instagram account with a long manifesto informing its followers about the action and its motives. It soon became one of their most liked posts on Instagram.

In both countries, the production of online visuality encompassed multiple temporalities – the anticipation and organisation of the picture-taking and video-recordings, the collective choices regarding the management of online public visibility and the backstage/onstage blurring in the visual enactment of the protest. The latter aspect was particularly apparent in the more performatively demanding protest, the Red Brigade. While in the Finnish die-in it was the succumbing assemble of bodies that visually marked the performance, making it aesthetically recognisable, the Portuguese Red Rebels required rehearsals, dress-ups and make-ups, as described in the fieldnotes of the protest’s preparations. In a die-in, bodies keep their humanity and relatability: coming as they are, absent of distinctive clothes or features, the protesting bodies that synchronously fall are anyone’s body (Butler Citation2004). The photographic gaze visually constructs the collective body, vulnerable and deceasing. In the Red Rebels, the bodies’ reconfiguration and the internationally known visual markers became part and parcel of the protest’s online visuality – ranging from the faces being painted white to the red robes being rolled out around the bodies. As described in the previous section, the protest’s preparations in Portugal entailed a great deal of effort to transform the bodies into deliberately gender-neutral or seemingly identity-stripped bodies – a ritualised process that was recorded to visually construct a renewed collective body. The protest was already happening before it ‘actually’ started.

A video posted on social mediaFootnote6 of the protest begins with images of the Portuguese activists gathered in a private house, getting their faces painted, smiling and interacting with one another (see ). It then progresses towards the moments when they step into the street, adopting the choreographic slow-motion style, expressionless faces and reactionless eyes (see ). The online ‘stage’ was thus used to present the transformation of the bodies from private (house) to public (street), in which the activists ceased to be individuals and became a cohesive collective body. By providing online viewers with glimpses of those private moments, the Portuguese activist group sought to make the Red Rebels more relatable and to symbolically lay the foundation for the transformation that the protest espouses. Casquete (Citation2003) suggested that one of the most exceptional functions of ritual is the blurring between self and others, when new actors and identities are created before, during and after a protest. However, this blurring does not take place only among the protestors: the ritualised process becomes a resource of its own when mediated online, calling for precisely the sense of collectiveness that a new future should entail.

Image 1. Screenshot from social media of a video posted by the Portuguese Extinction Rebellion, showing the preparation of the Red Brigade.

Image 2. Screenshot from social media of a video posted by the Portuguese Extinction Rebellion, showing the Red Brigade in the street.

In Finland, the visual online representation of the die-in protest focused on highlighting the bodies in the middle of Christmas shopping (see ), while on the street the protest was ‘performed’ to an audience of passers-by. The ‘living’ and shopping bodies became actors, as it is the combination of the ‘dead’ bodies on the pavement and the living bodies around them that creates the visual dissonance pivotal to the ritual (see ). Although the die-in loses its disruptive spatial dimension on social media –most importantly, physically blocking the entrance to the department store – the symbolic meaning of the time and place of the protest ritual does not disappear. Instead, it is the time and place that create an interpretative frame for the images.

Image 3. Screenshot from social media of a picture posted by the Finnish Extinction Rebellion, showing the Die In in the street.

Image 4. Screenshot from social media of a picture posted by the Finnish Extinction Rebellion, showing the public reactions to the Die In.

Bodies are the visual essence of the images shared online from both countries. In the Finnish case, rather than a portrait of individual bodies, the pictures seem to visually frame a collective body (several bodies dying-in) succumbing to the climate catastrophe. On the other hand, the video produced by the activists in Portugal depicts the red-robed Brigade performing synchronised movements; in addition, images depicting the robes lend a ritualistic tone to the protestors’ preparations. The Red Rebels’ bodies prefigure an alternative cultural system, embodying the very claim at stake in the protest. Individualised and capitalistic logics are confronted when the masked bodies occupy the public space, with online images contrasting the slow-motion and contemplative bodies with those agitated and careless bodies driven by Black Friday sales. In turn, in the online space, the bodies of the passers-by were transformed into a crucial element of the visual narrative of the protests in both Portugal and Finland.

CONCLUDING DISCUSSION

This article provides a hitherto unexplored avenue of research focusing on both the immediate and mediated aspects of protest performances through an emphasis on the concept of ritual and the use of methodological tools combining snap-along ethnography and coordinated comparative fieldwork. Even though the analysis builds on two separate protest performances by the same movement, the comparative view is fruitful because of the abundance of shared protest features: the crucial role of bodies as tools of protest visibility, the resignification of the same types of spatial and material environments, the intertwinement of offline and online protest practices and the reference to prior international examples of similar protest performances. In both Finland and Portugal, the protests were highly performative and visually oriented – characteristics that are well-known key features of the international movement. This argues against viewing the protests as culturally specific and for focusing on their converging and differing characteristics, resulting in the micro-comparative design with a shared theoretical optic that is presented in this article. Such a methodological strategy enabled us to see strikingly similar aspects in both cases; otherwise, these could easily be either overlooked or interpreted as country-specific features. Indeed, despite their different backgrounds and cultural contexts, both protests unfolded in immediate and mediated ways, reproducing ritualised, internationally-patterned features.

The preponderance of bodily visual claims over cultural and linguistic specificities reinforces the importance of paying attention to non-verbal levels of political action and argumentation (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022), as well as to the ritual as ‘a type of embodied discourse’ (Hurd Citation2014, 289). In line with the concept of ritual, both protests emphasised visuality, physical embodiment and connotation: the performances might be difficult to translate into words, but nevertheless, both visually and vividly communicate a message of urgency, grounding their legitimacy ‘in the sincerity and commitment of the protestor, and in the emotional reactions of the viewer’ (Szerszynski Citation2002, 55). As shown, online visuality was an integral part of the protest – how its claims were articulated and how its ritualised forms were shaped (see Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022) – potentiating an ‘embodied reading and cultural understanding of the performance without having to put it into spoken discourse’ (Hohle Citation2010, 48).

The two XR Black Friday protests, carried out on the same day in Finland and Portugal and examined in parallel as ritualised embodied performances, enabled us to grasp the key roles that bodies play as tools of visibility. We first focused on understanding these actions as ritualised protests, then on the role of bodies as tools of protest visibility in the intertwinement of the offline and online spheres. At the immediate level, we analysed how bodies primarily assumed the role of bringing rituals to life. Bodies functioned as enactors of a spectacle that was presented to be photographed, almost as an art piece, and the role of the passers-by was that of spectators and not interactors – unlike demonstrations, people could not join in. At the mediated level of protest, we looked at bodies as artifacts that compose narratives of futures, dystopian and utopian, of extinction and of regeneration. We suggest that at the immediate level, the bodies played an instrumental role (enactors of ritualised protest performances on the street), while at the mediated level, the bodies played a narrative role (tools of visual dissonance and cultural prefiguration on social media).

Far from a ready-made process, the ethnographic data showed how bodies’ transformations did not occur without emotional uneasiness. Still, as shown, the nervousness about bodily interrupting Christmas shopping in Finland and the insecurity of publicly performing a Red Brigade in Portugal were soothed by means of ritualisation – engagement in predefined reliable patterns (Casquete Citation2003; Turner Citation1982). This suggests the role of protests’ ritualisation in sustaining bodily disruptive actions, considering that ‘direct action is praxis, catharsis, and image all rolled into one (…): it is literally embodying your feelings, performing your politics’ (Jordan Citation1998, 134). This ritualised process seems not only to have contributed to the protestors’ confidence in both countries; also, in the Portuguese case, the very process of the body’s reconfiguration became part and parcel of the protest that was being forged in the offline-online fluctuation. This may be illustrated by the enthusiastic exclamation of an activist looking in the mirror – ‘We can hardly recognise each other!’ – while another activist circulated around the room, photographing and recording such moments, which would later feature in the online visual framing of the protest. Thus, the visual construction of bodies commenced even before the protest reached the street.

In both countries, the online images depict an embodiment of a different ontological scenario, juxtaposing different kinds of ‘bodies’: in Finland, the ‘unlived bodies’ interrupting the bodies living their lives as usual and passing by in the buzz of Christmas shopping, and in Portugal, the ‘dystopic slow-motion bodies’ among the hurried urban bodies. This contrast comes close to Turner’s (Citation1982) concept of the indicative and the subjunctive, ‘the relationship between what is and what could otherwise be the case’ (Szerszynski Citation2002, 56). This was highlighted in both protests, as the bodies, whether lying silently or slowly making their way through crowds, drew attention to different imagined futures. In the case of Portugal, a utopian future was represented by bodies that contrasted, through their slow and contemplative movements, with those around them. In Finland, the dystopian performance portrayed a grim vision of the future that was aimed at exposing the reality behind the ‘normal’. The die-in challenged normative ideals of consumption by exposing people to the ‘reality’ of their behaviour. Importantly, the narration of utopian and dystopian futures is only possible by changing, at the online level, one of the features of the protest ritual: the gap between the audience and the protestors. This distance, part of the protest’s immediate unfolding, is transformed into something new.

The literature on ritualised protests, embodied performances and online visuality facilitated understanding of the role of the body in current radical climate movements. By examining the changing ritualistic features of the protest in the offline-online conjunction, we argue that bodies are visually constructed to operate as sites of imagination. In the offline sphere, the ritualised performances were enacted as the protesting body was reconfigured in its public dimension, as a body that both is and is not the body of the protester (Butler Citation2004). This was done through preparations and ornamentations of the bodies, predefined standardised corporeal behaviours and a heightened sense of display before others. While these ritualistic features facilitated the protest’s replication across countries, its public recognisability and the activists’ engagement in direct action, the connotative function of the ritual was fulfilled at the mediated level. In the online dimension, the spectators were recreated as actors whose bodies – in dialectic with the protesting bodies – symbolically condensed the lived and the imagined worlds through a visuality that simultaneously evokes and blurs dichotomies: fast-paced consumerism and ecologically compassionate living, self and other, vulnerability and agency, disaggregation and unification. Although bodies were visually constructed to encapsulate both contradictions and alternatives to the current capitalist system, the ritualised process through which political demands were performed may render them resistant to refutation. In fact, as pointed out by Szerszynski (Citation2002, 60), contrary to denotative forms of communication, ritual action ‘resists incorporation into conventional justificatory regimes (…) [because] if rites have no contrary, how can one argue against a ritualised politics, one that repeatedly if not always avoids conventional “rational” argument?’ Building on this question, and having distilled the offline-online visual construction of bodies, our article hints at how a heightened visuality in ritualised forms of protest seems to contribute to the disavowal of negotiable and conventional argumentative formats of claim-making.

This article, then, contributes to challenging the notions of online visuality as an exclusively a posteriori space used to represent physically rooted protests (cf., Gonzalez Citation2022), the distant status of audiences in spectacle-oriented public spheres (cf. Adut Citation2018), and even the dichotomous conceptualisation of ‘the body as actor [and] the body as acted upon’ (cf. Bhatia Citation2022, 638). By analysing two exemplary protests of the XR movement, we have shown that, more than mere bodily public disruptions using the online sphere for far-reaching exposure, these actions’ meanings are only fully forged in the offline-online fluctuation.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carla Malafaia

Carla Malafaia is a principal researcher at the University of Porto - Centre for Research and Intervention in Education at the Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences (DOI: 10.54499/CEECINST/00134/2021/CP2786/CT0002). She is involved in the ERC-funded project “Imagi(ni)ng Democracy: European Youth Becoming Citizens by Visual Participation” and her research interests include youth citizenship, social movements, visual politics and community intervention.

Jenni Kettunen

Jenni Kettunen is a doctoral researcher at the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Helsinki.

Eeva Luhtakallio

Eeva Luhtakallio is a professor of sociology at the University of Helsinki. She specialises in political sociology, social theory and sociological methods. Her work focuses on democracy and citizenship as culturally patterned practices, including studies on young people's activism and visual politics. She leads the ERC-funded project “Imagi(ni)ng Democracy: European Youth Becoming Citizens by Visual Participation”.

Notes

2 We refer to the ‘walk-along’ or ‘go-along’ ethnography for its explicit mobile character. Still, the snap-along method, as an ethnography-based approach, draws on core ethnographic contributions – such as Goffman’s insights on, for example, the analytical value of looking at mundane practices performed in co-presence, managing impressions and shaping the ‘interaction order’ (e.g. Goffman Citation1974; Citation1983). Although this article focuses on a processual account of the immediate and mediated developments of performative protests, the snap-along method generates empirical data subject to diverse analytical angles – e.g., social and political tensions deriving from the activists’ interactions with social media architecture, with other social movements and with different power-holders (see e.g., Malafaia and Meriluoto Citation2022; Malafaia Citation2022).

5 All participants’ names are fictional to preserve anonymity.

6 Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CIbO1_7BczR/

References

- Adut, A. 2018. Reign of Appearances. The Misery and Splendor of the Public Sphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baer, H. 2016. “Redoing Feminism: Digital Activism, Body Politics, and Neoliberalism.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (1): 17–34. doi:10.1080/14680777.2015.1093070.

- Barassi, V. 2015. Activism on the Web: Everyday Struggles Against Digital Capitalism. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Benford, R. D., and S. A. Hunt. 1992. “Dramaturgy and Social Movements: The Social Construction and Communication of Power.” Sociological Inquiry 62 (1): 36–55.

- Bhatia, K. V. 2022. “The Revolution Will Wear Burqas: Feminist Body Politics and Online Activism in India.” Social Movement Studies 21 (5): 625–641. doi:10.1080/14742837.2021.1944850.

- Butler, J. 2004. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 2011. “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street.” In Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Activism, edited by M. McLagan, and Y. McKee, 117–137. New York: Zone Books.

- Butler, J. 2015. Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Casquete, J. 2003. “From Imagination to Visualization: Protest Rituals in the Basque Country.” (Discussion Papers / Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, Forschungsschwerpunkt Zivilgesellschaft, Konflikte und Demokratie, Arbeitsgruppe Politische Öffentlichkeit und Mobilisierung, 2003–2401). Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung gGmbH.

- Clément, K., and E. Luhtakallio. 2021. The French yellow vests movement and the visual orders of class [Paper presentation]. American Sociological Association (ASA) Conference, online. August 8.

- Coffey, J., and A. Kanai. 2023. “Feminist Fire: Embodiment and Affect in Managing Conflict in Digital Feminist Spaces.” Feminist Media Studies 23 (2): 638–655. doi:10.1080/14680777.2021.1986095.

- Coombs, G. 2020. “It’s (Red) Hot Outside! The Aesthetics of Climate Change Activists Extinction Rebellion.” The Journal of Public Space 5 (4): 123–136. doi:10.32891/jps.v5i4.1407.

- Del Gandio, Jason. 2015. “Activists, Bodies, and Political Arguments.” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies 11 (4): 1–13.

- DeLuca, K. M. 2021. “Extinction Rebellion, Image Events, Social Media and the Eclipse of the Earth.” Social Anthropology 29 (1): 216–218. doi:10.1111/1469-8676.13002.

- Doerr, N., and S. Teune. 2012. “The Imagery of Power Facing the Power of Imagery: Toward a Visual Analysis of Social Movements.” In The Establishment Responds. Power, Politics and Protest Since 1945, edited by K. Fahlenbrach, M. Klimke, J. Scharloth, and L. Wong, 43–55. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Doherty, B. 2000. “Manufactured Vulnerability: Protest Camp Tactics.” In Direct Action in British Environmentalism, edited by B. Seel, M. Paterson, and B. Doherty, 62–78. London: Routledge.

- Fasnacht, H. 2021. “The Narrative Aesthetics of Protest Images.” The Journal for the Philosophy of Language, Mind and the Arts 2 (1): 221–238. doi:10.30687/Jolma/2723-9640/2021/01/013.

- Faulkner, S. 2020. “Photography and Protest in Israel/Palestine: The Activestills Online Archive.” In The Aesthetics of Global Protest: Visual Culture and Communication, edited by A. McGarry, I. Erhart, H. Eslen-Ziya, O. Jenzen, and U. Korkut, 151–170. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.1515/9789048544509-011.

- Feola, M. 2018. “The Body Politic: Bodily Spectacle and Democratic Agency.” Political Theory 46 (2): 197–217. doi:10.1177/0090591717718526.

- Fotaki, M., and H. Foroughi. 2022. “Extinction Rebellion: Green Activism and the Fantasy of Leaderlessness in a Decentralized Movement.” Leadership 18 (2): 224–246. doi:10.1177/17427150211005578.

- Goffman, E. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Goffman, E. 1983. “The Interaction Order: American Sociological Association, 1982 Presidential Address.” American Sociological Review 48 (1): 1–17.

- Gonzalez, V. 2022. “Embodiment in Activist Images: Addressing the Role of the Body in Digital Activism.” Media, Culture & Society 44 (2): 247–265. doi:10.1177/01634437211060199.

- Gordon, G. 1956. “The Sociology of Ritual.” The American Catholic Sociological Review 17 (2): 117–130.

- Greene, A. K. 2021. “Flaws in the Highlight Real: Fitstagram Diptychs and the Enactment of Cyborg Embodiment.” Feminist Theory 22 (3): 307–337. doi:10.1177/1464700120944794.

- Hohle, R. 2010. “Politics, Social Movements, and the Body.” Sociology Compass 4 (1): 38–51. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00260.x.

- Hurd, M. 2014. “Introduction: Social Movements: Ritual, Space and Media.” Culture Unbound 6: 287–303. doi:10.3384/cu.2000.1525.146287.

- Jasper, J. M., and J. D. Poulsen. 1995. “Recruiting Strangers and Friends: Moral Shocks and Social Networks in Animal Rights and Anti-Nuclear Protests.” Social Problems 42 (4): 493–512. doi:10.2307/3097043.

- Jordan, J. 1998. “The art of Necessity: The Subversive Imagination of Anti-Road Protest and Reclaim the Streets.” In Diy Culture: Party & Protest in Nineties Britain, edited by G. A. Mckay, 129–151. London: Verso Books.

- Juris, J. 2015. “Embodying Protest: Culture and Performance Within Social Movements.” In In Anthropology, Theatre, and Development, edited by A. Flynn, and J. Tinius, 82–104. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137350602_4.

- Kharroub, T., and O. Bas. 2016. “Social Media and Protests: An Examination of Twitter Images of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution.” New Media & Society 18 (9): 1973–1992. doi:10.1177/1461444815571914.

- Kusenbach, M. 2003. “Street Phenomenology: The Go-Along as Ethnographic Research Tool.” Ethnography 4 (3): 455–485.

- Lammert, C., and K. Sarkowsky. 2010. Travelling Concepts: Negotiating Diversity in Canada and Europe. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-92139-6_1.

- Lamont, M., and L. Thévenot. 2000. Rethinking Comparative Cultural Sociology: Repertoires of Evaluation in France and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Liinason, M. 2023. “The Performance of Protest: Las Tesis and the new Feminist Radicality at the Conjunction of Digital Spaces and the Streets.” Feminist Media Studies, doi:10.1080/14680777.2023.2200472.

- Luhtakallio, E. 2012. Practicing Democracy. Local Activism and Politics in France and Finland. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Luhtakallio, E. 2013. “Bodies Keying Politics: A Visual Frame Analysis of Gendered Local Activism in France and Finland.” In Advances in the Visual Analysis of Social Movements (Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and change), (Vol. 35), edited by N. Dörr, T. A. Mattoni, and S. Teune, 27–54. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Luhtakallio, E., and T. Meriluoto. 2022. “Snap-along Ethnography: Studying Visual Politicization in the Social Media age.” Ethnography, doi:10.1177/14661381221115800.

- Luhtakallio, E., and I. Tavory. 2018. “Patterns of Engagement: Identities and Social Movement Organizations in Finland and Malawi.” Theory and Society 47: 151–174. doi:10.1007/s11186-018-9314-x.

- Malafaia, C. 2022. “‘Missing School Isn’t the end of the World (Actually, it Might Prevent it)’: Climate Activists Resisting Adult Power, Repurposing Privileges and Reframing Education.” Ethnography and Education 17 (4): 421–440. doi:10.1080/17457823.2022.2123248.

- Malafaia, C., and M. Meriluoto. 2022. “Making a deal with the devil? Portuguese and Finnish activists’ everyday negotiations on the value of social media.” Social Movement Studies, doi:10.1080/14742837.2022.2070737.

- Mattoni, A., and S. Teune. 2014. “Visions of Protest. A Media-Historic Perspective on Images in Social Movements.” Sociology Compass 8 (6): 876–887. doi:10.1111/soc4.12173.

- McGarry, A., I. Erhart, H. Eslen-Ziya, O. Jenzen, and U. Korkut. 2020. The Aesthetics of Global Protest: Visual Culture and Communication. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvswx8bm.6.

- Milan, S. 2015. “When Algorithms Shape Collective Action: Social Media and the Dynamics of Cloud Protesting.” Social Media + Society 1 (2): 205630511562248–205630511562210. doi:10.1177/2056305115622481.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 1994. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Neumayer, C., and L. Rossi. 2018. “Images of Protest in Social Media: Struggle Over Visibility and Visual Narratives.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4293–4310. doi:10.1177/1461444818770602.

- O’Neill, M., and B. Roberts. 2020. Walking Methods. Research on the Move. London: Routledge.

- Rogoff, I. 1998. “Studying Visual Culture.” In Visual Cultural Reader, edited by N. Mirzoeff, 14–26. London and New York: Routledge.

- Rothenbuhler, E. W. 1988. “The Liminal Fight: Mass Strikes as Ritual and Interpretation.” In Durkheimian Sociology: Cultural Studies, edited by J. C. Alexander, 66–89. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sauerborn, E. 2021. “The Politicisation of Secular Mindfulness – Extinction Rebellion’s Emotive Protest Practices.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 9 (4): 451–474. doi:10.1080/23254823.2022.2086596.

- Schneider, B., and T. Nocke. 2014. “Image Politics of Climate Change: Introduction.” In Image Politics of Climate Change, edited by B. Schneider and T. Nocke, 9–26. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. doi:10.14361/transcript.9783839426104.intro.

- Seppänen, J. 2006. The Power of the Gaze: An Introduction to Visual Literacy. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Szerszynski, B. 2002. “Ecological Rites: Ritual Action in Environmental Protest Events.” Theory, Culture & Society 19 (3): 51–69.

- Treré, E. 2019. Hybrid Media Activism: Ecologies, Imaginaries, Algorithms. New York: Routledge.

- Turner, V. 1982. From Ritual to Theatre. The Human Seriousness of Play. New York: PAJ Publications.

- Weaver, D. 2022. “Extinction Rebellion: Greening Vanguardism?” Social Movement Studies, doi:10.1080/14742837.2022.2095997.