ABSTRACT

Miriam Katin's two graphic memoirs We Are on Our Own [(2006). Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly] and Letting It Go [(2013). Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly] both reflect on how the trauma of the Holocaust can be transformed through and in art. In the former Katin details how she and her mother narrowly escape the Nazi occupation of Hungary by fleeing to the countryside when she was a toddler, while the latter shows how Katin, who has since emigrated to the United States, is still struggling with anxieties decades after, which are the result of the Holocaust. Using insights from both memory studies and Bessel Van Der Kolk's experimental psychological theories that trauma is an embodied experience and that it can be partly released through physical and creative practices, this essay argues that Katin finds solace through the multimodal activity of drawing and writing herself out of the negative aftereffects that the Holocaust have on her.

The Hungarian American graphic artist Miriam Katin completed two graphic memoirs about her Holocaust experience. The critically acclaimed We Are on Our Own (Citation2006) details Katin's mother's and her own harrowing escape from Budapest after the Nazis usurped the city, while Letting It Go (Citation2013) tells of Katin's painful acceptance of her son taking Hungarian citizenship and deciding to live in Berlin decades after the war. This paper argues that Katin's graphic metamorphosis of trauma involves three steps. Katin's process of healing reflects, firstly, the importance of sharing intergenerational memory since Katin learns a more comprehensive story of the war years from her mother, and passes on her own memory to her son. Although visually divergent, We Are on Our Own and Letting It Go both show how communicative memory – “based on forms of everyday interaction and communication” – is passed on through the generations (Erll Citation2011, 28). Yet the two graphic memoirs are themselves also examples of collective memory that preserve the memory of the Holocaust in a cultural form. Secondly, both memoirs emphasize the power of multimodal creativity, as finding words, visualizing a past experience, and listening to music are essential to Katin's finding a hidden wholeness inside herself. Thirdly, the graphic diptych reflects on the Holocaust as a case of transnational memory and trauma. Only by literally and figuratively transcending boundaries – mental, cognitive, national – is Katin able to both integrate and let go of the most painful memories of her childhood trauma. Drawing on new findings from experimental psychology by Bessel Van Der Kolk, and also trauma studies, this article traces Katin's attempt to draw herself out of the trauma of the Holocaust through graphic memoirs. After reading a draft of this article, Katin commented on many of these points, confirming that she never “had analysis or sought psychiatric help” and that she is “not a spiritual person,” but that she found her own way to confront and come to terms with the overwhelming past of her infancy (Email correspondence Citation2017).

Like Art Spiegelman's classic Maus, Katin's two graphic memoirs are steeped in intergenerational memory. The first part of The Complete Maus – A Survivor's Tale: My Father Bleeds History is framed by Spiegelman drawing out his father, Vladek's, Holocaust story which we as readers listen in on as he imparts it to his son. The second part, And Here My Troubles Began, retells Vladek's narrative “From Mauschwitz to the Catskills and Beyond,” as Spiegelman summed it up with humourless irony (and a painful pun intended). By the time Spiegelman wrote the second part, however, the first part of Maus had already been published, having been enthusiastically received by the critics, and becoming a commercial success. In the meantime, Vladek had died and Art's wife Françoise Mouly became pregnant with their daughter. On one of the most haunting pages of The Complete Maus, Spiegelman reflects on these facts while picturing himself slouched over his writing desk positioned eerily on a pile of dead mice. As publishing and putative movie deals are pouring in, Spiegelman feels he is profiting from his father's and millions of other Jews’ suffering during World War II (Spiegelman Citation2003, 201).

This sense of survivor's guilt and the inability to let the bliss of parenthood sink in surfaces in Katin's We Are on Our Own too. Katin's first Holocaust memoir is mainly set during the Holocaust, and focuses on the bond she shares with her mother. This is similar to A Survivor's Tale: My Father Bleeds History where the Holocaust narrative of an adult witness is the predominant theme but the relationship between father and child is a significant subtheme. We Are on Our Own details the agonizing journey that Katin's mother and Miriam undertake from Budapest to the Hungarian countryside in 1944. Until 1943, it appeared as if Hungarian Jews would survive World War II unscathed, but when Nazi Germany occupied Hungary on 19 March 1944, the situation for mother and daughter became dire, especially when a ghettoization plan was being imposed in Budapest (Braham Citation2000, 13, 155). Whereas Spiegelman was born three years after the war and found out about the Holocaust through the communicative memory of his father, Katin was born in 1942 and lived through the war herself. Yet since children usually do not remember any childhood events before the age of three and a half, it is doubtful that Katin writes from personal experience. It is more likely that her mother, who also features briefly in Letting It Go, told her the stories which she moulded into We Are on Our Own. Yet whether the stories are dimly remembered or inherited, Katin, along with other child survivors became “possessors of deeply internalized abnormal, dehumanizing experiences, with enduring effects on their future life” (Mihǎilescu Citation2014, 74). It appears that Katin is drawing from “an imaginative investment and creation” rather than relying on “recollection,” a process which Marianne Hirsch (Citation1997) describes as “postmemory” (22). As Derek Parker Royal (Citation2016) has argued, Katin “takes the reader into uncharted postmemorial territory” by presenting Miriam's “passive and innocent firsthand” experience, although indirectly she is also the “mediator of her parents’ experience” (204). Not having an extensive memory of the Holocaust herself, she needs to rely on other means to understand her mother's and her own trauma, and creating graphic narratives is Katin's way of achieving this.

Even though the bond between Katin's mother, who understands the full extent of the horror that is unfolding around her, and her uncomprehending toddler daughter is central to the narrative of We Are on Our Own, we also catch glimpses of Katin's young son Ilan and her in New York many years later. This relationship became the main motif in Katin's second graphic memoir Letting It Go. This foreshadowing occurs only half a dozen times throughout We Are on Our Own, and immediately stands out for the reader due to what Jan Baetens and Hugo Frey call “the chromatic code” (Citation2015, 140). The single pages devoted to Katin's memories as a young mother in New York are depicted in dreamily romantic colours whereas the rest of the book is drawn in bleak black-and-white pencil drawings occasionally offset only against the intrusion of the blood red colour of the Nazi swastika flag and that of the advancing Soviet Union. Katin's use of colour in We Are on Our Own and Letting It Go is as symbolic as it is functional in reflecting on her childhood trauma. Whereas We Are on Our Own is entirely in black and white, except for those few instances that foreshadow a more blissful future, Letting It Go is entirely in colour, except for the flashbacks when Miriam conjures up the war.

Becoming a mother in the late 1960s seems to trigger, if not real memories, then at least thoughts and stories of Miriam's own upbringing. One of the colourful six single-page memories of raising Ilan, for instance, shows Miriam reading him the story of God's creation from My First Bible. It directly corresponds to the opening of We Are on Our Own where young Miriam and her mother read together in the Torah about how “God divided the Light from the Darkness,” as Katin's mother reflects (4). Becoming a mother makes Katin empathize with her own mother, come to terms with the hardships her mother endured, and relive these that she never consciously witnessed. The making of the graphic novel is thus an active conjuring up and understanding of her mother's trauma. Not only did Katin's mother have to take care of young Miriam alone, with her husband away in the army, while fleeing to the Hungarian countryside where she knew nobody, she also had to sleep with a Nazi officer for self-preservation and to safeguard her daughter.

The contrast between how Katin's mother and young Miriam experience and comprehend their period in hiding is one of the most compelling features of We Are on Our Own. Katin's mother shields her daughter from the harsh truths of their new reality, forcing Miriam to construe a logical story out of events, as a girl her age would do. Miriam dotes on her dog Rexy, which Katin's mother relinquishes to the Nazis when Jews are no longer allowed to keep dogs. Katin's mother makes up the white lie that Rexy has died and gone to “doggie heaven” (17). As a consequence the young girl bonds with every dog they encounter in the countryside. She also tries to comprehend how life and death, as well as God and heaven, can be understood, a puzzle she cannot quite solve. The girl's imaginings about this, which already started on the first page with her reading the Torah with her mother, are necessarily naïve. Yet they also touch on the larger issues, such as Holocaust theology, the debate about how a just God could allow a Holocaust to happen. When Katin's mother is pursued by a Nazi officer who fancies himself in love with her, she knows that resisting his advances would mean exposing her daughter and herself to potentially disastrous consequences. Miriam, however, comes to the conclusion that “maybe he is god,” as he gives her chocolate (42). When she catches her mother crying each time “Herr Commandante” leaves, the child reasons that her mother must miss “the nice man” (43). The dramatic irony that Katin's mother needs to have sex with a German officer for them to survive (as is her near-rape by a Soviet soldier later on) is lost on young Miriam, but not on the author writing and drawing this graphic memoir, nor on the reader. The dichotomy between the child's point of view captured in the captions and the adult's perspective which the visual text spells out for the reader shows how valuable the medium of a graphic novel can be by showing multiple perspectives on one historical event.

Like We Are on Our Own, Letting It Go revolves around intergenerational memory, and more specifically around family memory. “Through the repeated recall of the family's past,” as Astrid Erll has written, “those who did not experience the past firsthand can also share in the memory” (Erll Citation2011, 17). Katin's husband Geoffry and her son Ilan did not live through the horrors of the Holocaust themselves, but it is clear in Letting It Go that they know the full extent of it through Katin. How exactly this family memory has been passed on is not disclosed in Katin's second graphic memoir the way Spiegelman does in The Complete Maus, but husband and son know how sensitive this memory is for her. In fact, Letting It Go is centred on Ilan's decision to move to Berlin and file for Hungarian citizenship, and his mother's reaction to it. This seemingly innocuous move by Ilan, who must be in his late 30s or early 40s at this time, occasions such emotional turmoil for his mother that it can only be understood as her belated response to the Holocaust. She knows that it is not her task to protect her grown son and that he should make these decisions on his own, but she is nevertheless distraught by his move. Katin, who calls herself a “manic old lady” in the acknowledgments, realizes how neurotic she is when it comes to Berlin and Germany. This is apparent to readers as well, from the first page onwards, in fact, when Katin draws images of German-made coffee machines in American kitchens. She admits that she believes that somewhere in Berlin someone will someday press a button that will blow up America. She knows the absurdity of this thought. Yet, this is something she cannot help but feel.

Katin's trauma is depicted in several ways. It is presented on a narrative level through the verbal and visual storytelling that she presents in both We Are on Our Own and Letting It Go. However, it is also expressed through page layout. We Are on Our Own features a stable page layout and panel content. No page is exactly the same, but most of the pages vary from four to nine panels, occasionally breaking this loose pattern for shock effect with a single-image (splash) page. Baetens and Frey define this conventional style as presenting “regular and discrete layouts […] combined with characters that are repeated panel after panel” (131). In Letting It Go, however, Katin also lets go of panels altogether, using an erratic and ever-changing page layout that reflects her volatile mind. This is “typically” found in “avant-garde graphic novels” (Baetens and Frey 131), which Katin's graphic memoir is clearly not. Benoȋt Peeters’ “Four Conceptions of the Page” are all relevant for understanding Katin's graphic memoir. Katin shifts from a conventional use of narrative and composition in We Are on Our Own to a style that is more rhetorical, and also dependent on the content in Letting It Go.

The more unsettled Miriam's mind becomes the more irregular the page layout becomes. When the page layout turns stable, it is an indication that Miriam is beginning to find her mental balance.

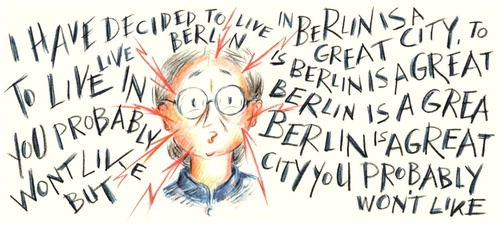

When Ilan announces his decision to relocate to Berlin, for instance, we see how her son's words, depicted in an aggressive and loud font, hit Miriam's face like red lightning bolts. This close-up of Miriam's face with Ilan's words booming in her mind and hovering on both sides take up a third of the page. When she discusses Ilan's situation and intentions with her ageing mother, for instance, who also lives in New York City, the page layout becomes more ordered. Her mother's soothing words (and Chivas Regal whisky) stabilize Miriam's weary mind somewhat. The way the Hungarian dialogue is depicted through a refined handwriting, in addition to a simpler boxed English translation, also contrasts sharply with the way Miriam receives Ilan's speech. In other words, not only do the unsteady page layout and virtual framing mirror Miriam's wobbly frame of mind, but changeable lettering and fitful fonts are also indicators of her troubled feelings.

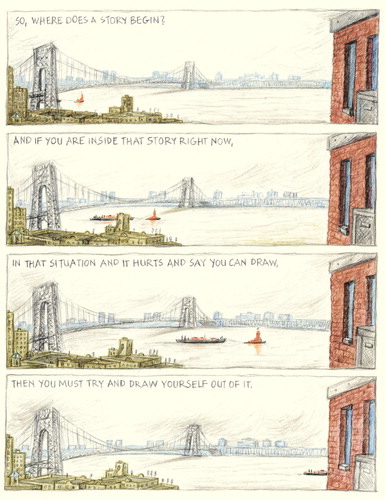

Only in those moments in Letting It Go when Miriam is staring at the Hudson River and the George Washington Bridge do the literal frames that were omnipresent in We Are on Our Own return to her narrative. These two New York landmarks ooze a sense of impermanence and frame her second graphic memoir in a figurative sense. The first time we see the Hudson River and the George Washington Bridge focalized through Miriam's eyes is nine pages into Letting It Go. After the unsettling opening in which Miriam admits that she imagines that somewhere in Germany someone is plotting to blow up America using exploding coffee machines, we see how Miriam is struggling with a writer's block. While her husband is playing Mozart on the clarinet, Miriam is unnecessarily cleaning her glasses, sharpening pencils, reordering her papers, and looking out of the window; anything but writing and drawing. She finds some comfort in Marcel Proust's musings about procrastination, but is morosely skulking around the apartment afterwards, until she is halted by the imposing view of the bridge under which a barge is being towed. In this evocative page with four panels that are horizontally aligned, spanning the entire width of the page, the reader sees how the barge slowly moves northwards over the Hudson. In the top-left hand corner, Katin expresses Miriam's thoughts in single lines, as if reciting lines of a poem: “So, where does a story begin? / And if you are inside that story right now, / In that situation and it hurts and say you can draw, / Then you must try and draw yourself out of it” (n.p., 9). It is on this self-referential page that Katin reveals both the motive and method behind her graphic memoir. She must try to draw herself out of the trauma she experienced as a child surviving the Holocaust.

Stories that reflect trauma contain “a kind of double telling,” as Cathy Caruth (Citation1996) has famously claimed, “the oscillation between a crisis of death and the correlative crisis of life: between the story of the unbearable nature of an event and the story of the unbearable nature of its survival” (8–9). If We Are On Our Own presents the crisis of death in which Katin and her mother desperately try to escape the Nazi death camps and subsequently the marauding Soviet troops, Letting It Go meaningfully constitutes the less familiar crisis of life. Life for Miriam Katin after the Holocaust is not filled with the kind of rose-coloured postwar moments that appear sporadically in We Are On Our Own after all. Instead Letting It Go shows Miriam's constant struggle to maintain her equilibrium concerning seemingly ordinary events. “The survivor's energy,” as Bessel Van Der Kolk has argued, is “focused on suppressing inner chaos,” which is shown throughout the narrative of Letting It Go, but also in the page layout. Yet this occurs “at the expense of spontaneous involvement in their life” (Van Der Kolk Citation2014, 53). Miriam's husband and Ilan react to unexpected changes in life with humour and a sense of perspective, and perhaps surprisingly Miriam's mother does that too. Although Miriam's mother only appears on a few pages in Letting It Go, she seems on the face of it, less affected by trauma than Miriam is.

This could point to the general fact that no two people react to traumatic experiences in exactly the same way, but another way of explaining the difference in response might be the dissimilar circumstances of how they survived the Holocaust. Van Der Kolk has explained how “effective action versus immobilization” (54) is a crucial difference in explaining why some people are traumatized and others are not. Trauma is more likely to occur when people are trapped in a harmful situation with no agency, chance, or possibility of escape. As a consequence, the “brain keeps secreting stress chemicals, and the brain's electrical circuits continue to fire in vain” (54). Van Der Kolk's description of the febrile brain's overdrive is not unlike Katin's portrayal of Miriam's face when she hears that Ilan wants to move to Berlin. When stress hormone levels remain high, they cause anger, dread, depression, and also make people more prone to physical disease. “Immobilization keeps the body in a state of inescapable shock and learned helplessness,” as Van Der Kolk argues, which is, in fact, an accurate reflection of what Katin's early childhood was like. As a hapless child caught in a war and afterwards a revolution, she was constantly in a vulnerable, dependent, and powerless position which makes lingering trauma more likely.

Katin's mother escaped to the same places as her young daughter did, and arguably endured more hardship than Katin herself did, as We Are On Our Own seems to indicate. She has to burn all possessions, sell family heirlooms, has to lie to friends and family members, has to endure untoward advances from several men and succumb to them on occasion for sheer survival. Yet by actively choosing to leave Budapest and run to the countryside, Katin's mother had a clearly discernible influence on her and her daughter's ultimate survival. By the spring of 1944, the Budapest ghetto was becoming a reality, and the Nazi killing machine was making haste to subject the Hungarian Jewry “to the most ruthless and concentrated destruction process of the war” (Braham 13). Some of the gruesome facts of the “Final Solution” until then, however, were known to Hungarian Jewry, including Katin's mother, as We Are On Our Own confirms. Despite the hard times she had to face and the compromises she had to make in their escape route to the countryside, she acted quickly and with resolve, thereby giving herself a sense of agency. This is a “technical term for the feeling of being in charge of your life,” as Van Der Kolk has indicated: “knowing where you stand, knowing that you have a say in what happens to you, knowing that you have some ability to shape your circumstances” (95). It is the mother's sense of resolution and her skills of improvisation that enable them to survive. It is this “knowing what you can do can make a difference” that breeds “resilience,” and ultimately makes Katin's mother less prone to trauma.

Decades after the war, Miriam, however, is still struggling with her sense of powerlessness in the face of the changing world around her. Yet as the meaningful page of the barge slowly gliding over the Hudson River and underneath the George Washington Bridge suggests, Miriam, too, is resolved to get the Holocaust out of her mind. As the superscript of the final panel of this page states, Miriam “must try and draw” herself out of it, which she does in Letting It Go, both literally and figuratively. The verb “to draw out” can mean to remove or to extract. On a metaphorical level, it suggests that Miriam realizes that she needs to get out of her self-defeating situation. Yet the verb can also mean to cause to speak freely. This usually refers to someone else who is encouraged or prompted to articulate himself or herself without restraint, but Miriam's text in the bottom panel indicates that she feels the need to allow herself to voice herself in an unencumbered way. On a literal level, especially in the context of Miriam's profession as a graphic artist, drawing out, however, brings in a third meaning, namely that she cannot only speak and write about her trauma, but that she also needs to visualize it to herself.

The inherently multimodal form of graphic novels, combining text and image, proves to be a perfect medium for Katin to transform the most painful memories of her life and the negative reverberations they have on her present into a more positive, forward-looking and life-affirming trajectory. We Are On Our Own shows this implicitly, but Letting It Go describes how she goes about that explicitly. It is a well-established truth in psychology that voicing one's trauma through a verbal narrative is conducive to the healing process. “Silence about the trauma,” as Van Der Kolk has argued, leads to “the death of the soul,” even though relating the traumatic event in words is excruciating too (Van Der Kolk Citation2014, 232). Yet “finding words where words were absent before and, as a result, being able to share your deepest pain and deepest feelings with another human being” is “fundamental to healing the isolation of trauma” (235). Throughout Letting It Go, we see how Miriam tries to communicate what plagues her about Ilan's impending move to Berlin. Although neither her husband and her son nor her friend Betty to whom she imparts her feelings can completely understand how she feels, the attempts are significant because they show her willingness to open up.

Miriam ostensibly does this without the help of a psychologist. There is no mention or reference to counselling or therapy in either We Are On Our Own or Letting It Go. In fact, even the titles of Katin's graphic memoirs emphasize self-help. During World War II it was necessary for them to fend for themselves in order to survive, but also in the aftermath of the war, Katin and her mother are resolved to do it on their own (albeit with a select group of friends and family). Even though Katin is not particularly drawn to psychology, it is nevertheless possible to use new findings in psychology and trauma studies to gauge the efficacy of Miriam drawing herself out of the trauma of the past. Since the days of Sigmund Freud, Western culture has emphasized, and perhaps overemphasized, talk therapy. Even though verbalizing trauma and writing to oneself and others has proven to be effective, contemporary psychologists stress “the limitations of language” as the single satisfactory strategy for healing (Van Der Kolk Citation2014, 235). Bessel Van Der Kolk propagates chipping away at the trauma by a variety of techniques, ranging from traditional talk therapy to experimental methods of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, including expressive therapies, such as yoga but also drawing. “This sets the stage for trauma resolution,” Van Der Kolk argues, “pendulating between states of exploration and safety, between language and body, between remembering the past and feeling alive in the present” (245).

After the crucial scene of Miriam staring at the Hudson River early on in Letting It Go, she is seen to be grappling with what the beginning, the middle, and the end of her story might be. She gets upset by bugs in her apartment and does some research on bugs, and draws them, while her husband's clarinet music resonates in the background. She also draws a page of her giving birth to a baby, Ilan, who was delivered with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck (Email correspondence Citation2017). Ilan survives, but this close call is once again a scary and intrusive reminder of the thin line between birth and death, between surviving and succumbing. Miriam muses quizzically that “this tale appears to have a floating centre” (Katin Citation2013, 18). Katin's entire narrative, however, is floating at this point in her graphic memoir, but chaos and detritus are part of her story.

Although research on drawing as a way of treating trauma is “scant,” there is increasing evidence to suggest that “drawing and painting can give observable form to pre-verbal traumatic memory and create a play space in which images can be seen, touched, reflected on, and remade” (Thompson Citation2014, 145, 139). All of the miniature stories that occur in these early stages of Letting It Go are related to Katin's trauma, but in oblique and imperceptible ways that do not make sense immediately. To Miriam, the bugs and the difficult labour are part of the story, but she has not exactly resolved how, and implicitly invites the reader to understand this conundrum too. Yet gradually these details become more coherent and cohesive and draw out a storyline that will help Katin to come to grips with her emotions.

Graphic novels have been credited with the “potential […] to open up new and troubled spaces,” as Gilian Whitlock has argued (Whitlock Citation2006, 976). Some of the most famous graphic novels, for instance Art Spiegelman's Maus, Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis, and Alison Bechdel's Fun Home are – like Katin's We Are on Our Own and Letting It Go – “personal memoirs,” as Baetens and Frey have indicated, even if the main character is not necessarily that of the “narrating I” (12). All these graphic memoirs are self-referential in terms of the writing process, as they reflect on the difficulty the graphic memoirists have in opening up these “new and troubled spaces.” It is the dual accomplishment of finding both appropriate words and images that allow the graphic memoirists to fill these spaces with a new narrative that does justice to both the pain of the past, but also the possibilities of the future. “Perhaps the central paradox of grieving is the need to hold on while letting go,” Leigh Davies has argued in an article about drawing as a practice of creating meaning when recovering from hardship, which ironically echoes the title of Katin's second memoir:

Do we have to let go? And what does it mean to do so? Metaphorical imagery allows holding on and letting go, grieving and creating, to occur simultaneously. A metaphor suggests something beyond what is immediately presented and offers more than one dimension, one meaning, or one route to a solution; that is its strength. (Davies Citation2014, 146)

As the other overarching metaphor in Letting It Go, of drawing oneself out of it, emphasizes, this is a concerted effort by Miriam herself who forces herself to look differently at her own life and past. Yet paradoxically, Letting It Go also shows that Miriam needs the help of other people as well. Miriam's husband is a musician, and throughout the narrative we see how the musical notes Geoffry makes infiltrate into Miriam's conscious or subconscious. Katin does not play a musical instrument herself, although she “did study did study piano as a child” and grew up “with the daily sound of playing” in Budapest. She acknowledges, however, how central music has remained in her life, and even calls it a “bandaid” to her soul, implying the supposed healing power of the arts, which Van Der Kolk and others have tried to establish (Email correspondence Citation2017). The clarinet sounds form the soundtrack of Miriam's search for appropriate words, images, and metaphors to let go of the past, to frame her new future narrative, and to create a new safe space for her in which to live and work. When Miriam's husband is practicing Richard Wagner's “Ride of the Valkyries,” Miriam is seen to be blown away by the German composer's bombastic opera theme, and she trips over the notes that her husband is playing. Yet even though she is down on the ground, it dawns on her that she needs “a leitmotif to carry me through this story” (Letting It Go 43). Ironically, the Germanic music, whether it is by Mozart or Wagner, that Miriam's husband is playing functions as a leitmotif throughout Letting It Go. It functions “as a theme” but also as “an associative entity” (Bribitzer-Stull Citation2015, xix).

It is here that Miriam begins to have a change of heart, about her son's departure for Berlin and about her past. Immediately following this revelation of Miriam's need for a leitmotif, we see her walking forlornly through her apartment until she stares out again at the George Washington Bridge and over the Hudson River. Hearing Wagner, who was an anti-Semite and was admired by Hitler, has triggered something ineffable, which Katin's drawing cannot capture either. Perhaps it is the understanding that if she can integrate German music in her life, she should be able to survive the confrontation with Germany in other parts of her life. Not only does Miriam agree to help her son acquire Hungarian citizenship, she also decides to face Berlin. She researches the history of the German capital online, trying to feel empathy for the victims of the firebombing and the Soviet invasion for which she felt no “compassion,” she reaches out to a former lover, a Turkish poet who lives in Berlin, and ultimately also decides to visit Berlin (49). By confronting Berlin, the capital of the former enemy, Miriam opens up to a transnational memory of the war that helps her to let go of the past even more.

It reminds her not to generalize, and to see that the fixed boundaries of the past that used to exist, between countries, but also between good and evil, are no longer there or so pronounced. The world has become a global village, as Miriam is finding out. Miriam's son Ilan, who was born an American citizen, will live as a Hungarian in Berlin with his Swedish girlfriend Tinet. This acceptance of a changed world allows her to look differently at the past too. When researching the war in the wake of her visit to Europe, Miriam is deeply moved by the story of Karol Józef Wojtyła, later Pope John Paul II, helping a Jewish girl who has escaped from a concentration camp. She is likewise intrigued by Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese diplomat who obtained visas for thousands of Jews in Lithuania, and whose monument Geoffry and Miriam stumble upon when visiting Vilnius. At the risk of his reputation, personal safety and that of his family, Sugihara chose to help Jewish refugees escape Europe. These stories help restore Miriam's sense of faith in humanity before setting foot in Germany, the country whose former citizens were out to kill her when she was little.

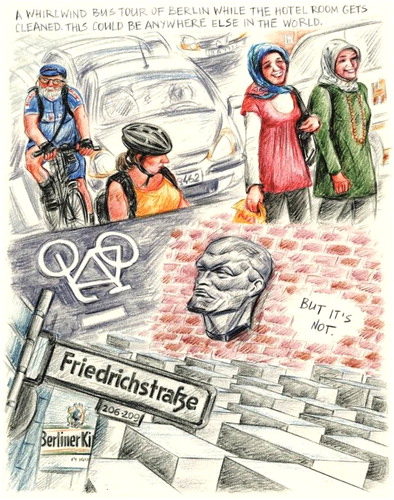

Miriam visits Berlin twice in one year at the end of Letting It Go, once to visit Ilan and a second time because work of hers is exhibited at the Jewish Museum. Even though she is plagued by an unexplainable bout of diarrhoea on one trip and an itching rash on the other, which could point to the psychological stress she experiences, Miriam perseveres, and eventually comes to enjoy the way Berlin has evolved as a city. During her first encounter she is split between a real appreciation of Berlin as a bustling international hub and her palpable disgust at the city's Holocaust history. This is best exemplified by the split-page technique Katin uses detailing her first experiences in the city on a “whirlwind bus tour.” The top half of the page shows a bearded, elderly man in fancy bike gear on a fancy bike and a younger helmeted woman, next to two laughing young women wearing headscarves. This is meant to show that the city now belongs to all ages, religions, and ethnic backgrounds. The text accompanying these images indicates that “this could” indeed “be anywhere else in the world,” including Miriam's native New York. “But it's not,” as the accompanying text soberly states, featuring an image of the bust of Lenin, a sign of the commercial shopping street Friedrichstrasse, and the stelae of the Holocaust Memorial. Katin draws our attention to the historic specificity of Berlin as a location, but she also (perhaps inadvertently) contextualizes the trauma of the Holocaust with the suffering and oppression of other groups, in this case those who were victimized by Communism. By doing this, Katin forces those who study how trauma is reflected in literature “to foster attunement to previously unheard suffering,” as Stef Craps has proposed more generally (Craps Citation2012, 4).

It also leads to a sarcastic page in which Katin imitates the style of postcards and advertises Berlin as the city that offers the “Holocaust memorial with pretzels,” “With ketchup and mustard,” “With soft ice cream,” and “Also, mit schlag.” This bifurcated view of the city is indicative of Miriam's ambivalent feelings towards Berlin.

During the second trip to Berlin, Miriam is more comfortable. Her divided mind becomes unified, like the city of Berlin and the country of Germany. The cobblestones that run all through the city to demarcate where the Berlin Wall once stood symbolize how Miriam manages to bring together what psychologists and neuroscientists have called a “split-brain” (Van Der Kolk 280). Standing with one foot in the East and one foot in the West, Miriam even gleefully acknowledges this fact a few pages from the end of Letting It Go. Intriguingly, she does this right in the middle of a conversation with Ilan's girlfriend Tinet teaching her the German compound word “Vergangenheitsbewältigung,” which means mastering or coming to terms with the past. What Berlin and Germany have to learn, Miriam has to as well. The “central task for recovery from trauma is to learn with the memories of the past without being overwhelmed by them in the present,” as Bessel Van Der Kolk has written, which also implies that Miriam has to “revisit traumatic memories in order to integrate them” (Van Der Kolk Citation2014, 279).

While the Berlin Wall has crumbled down in large parts of the city, Miriam has her own, temporary wall in Berlin's Jewish Museum. “My wall. I’m here. We made it,” she sighs close to the end of her second memoir, to which Miriam's husband responds with “Your wall.” The three staccato sentences that Miriam utters all meaningfully reflect on the long journey she has completed. The “wall” is more than that part of the room connecting floor and ceiling. It is hers because the artwork covering it is testimony to the recognition that she is receiving as an illustrator and graphic artist. The other two phrases bespeak Miriam's amazement that she is alive to witness this personal recognition for her art, but also that she has mustered the courage to visit Berlin and Germany, and to confront the past. The plural pronoun “We” refers to Geoffry and her, but implicitly also to her mother and her. They were on their own, but they made it.

The healing process is never complete, as the trauma of having survived the Holocaust will always reside in Miriam Katin's mind and body, and the past will never be eviscerated. Letting It Go ends with Geoffry and Miriam exiting their hotel on their way to the airport. All this while, Miriam is scratching herself, and the rash that was plaguing her all throughout the narrative is back with a vengeance. The bugs comically have the final word, and expect that Miriam will be back in Berlin. Like her Holocaust past, these bugs will continue to bug her. Yet Miriam has nevertheless metamorphosed. Not like Franz Kafka's character Gregor Samsa – whose picture Miriam stared at in a New York subway early in Letting It Go, and who was transformed into a horrific gigantic insect – but into a better adjusted person with agency who is ready to face her past, the present, and future again. Katin's resolve to recreate herself and her past is neither optimistic nor idealistic, as it lives “open eyed and wholehearted with the darkness that is woven ineluctably into the light of life,” to quote Krista Tippett, and which “sometimes seems to overcome it” (Tippett Citation2016, 233). Yet sometimes the good-natured spirit also recaptures itself, survives against all odds, and tries to let go to make something of life again.

Acknowledgement

Images reproduced with kind permission of Miriam Katin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Diederik Oostdijk is professor of English and American literature at VU University Amsterdam in the Netherlands. He is the author of Among the Nightmare Fighters: American Poets of World War II (2011) and finishing a book on the Cold War history of the Netherlands Carillon in Arlington, which will be published in 2019. He is especially interested in the aftereffects of war and trauma, and how these are mediated in different (artistic) forms and cultures.

References

- Braham, Randolph L. 2000. The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. Condensed Edition. Detroit: Wayne State UP.

- Bribitzer-Stull, Matthew. 2015. Understanding the Leitmotif: From Wagner to Hollywood. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Caruth, Cathy. 1996. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP.

- Craps, Stef. 2012. Postcolonial Witnessing: Trauma Out of Bounds. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Davies, Leigh. 2014. “Drawing on Metaphor.” In Grief and the Expressive Arts: Practices for Creating Meaning, edited by Barbara E. Thompson and Robert A. Neimeyer, 146–150. New York: Routledge.

- Erll, Astrid. 2011. Memory and Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Frey, Hugo, and Jan Baetens. 2015. The Graphic Novel: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Hirsch, Marianne. 1997. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory. Cambridge: Harvard UP.

- Katin, Miriam. 2006. We Are on Our Own. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly.

- Katin, Miriam. 2013. Letting It Go. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly.

- Katin, Miriam. 2017. Email Correspondence. June 20.

- Mihǎilescu, Dana. 2014. “Traumatic Echoes of Memories in Child Survivors’ Narratives of the Holocaust: The Polish Experiences of Michał Głowiński and Henryk Grynberg.” European Review of History – Revue Européenne D’Histoire 21 (1): 73–90. doi: 10.1080/13507486.2013.869791

- Parker Royal, Derek. 2016. Visualizing Jewish Narrative: Jewish Comics and Graphic Novels. London: Bloomsbury.

- Spiegelman, Art. 2003. The Complete Maus. New York: Penguin.

- Thompson, Barbara E. 2014. “Sketching Out the Story.” In Grief and the Expressive Arts: Practices for Creating Meaning, edited by Barbara E. Thompson and Robert A. Neimeyer, 139–145. New York: Routledge.

- Tippett, Krista. 2016. Becoming Wise: An Inquiry Into the Mystery and Art of Living. New York: Penguin.

- Van Der Kolk, Bessel. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Penguin.

- Whitlock, Gilian. 2006. “Autographics: The Seeing ‘I’ of the Comics.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 52 (4): 964–977. doi: 10.1353/mfs.2007.0013