ABSTRACT

Vera Bryce Salomons is best known as the founder of the L. A. Mayer Museum of Islamic Art in Jerusalem. Drawing on a privately published obituary volume, this article explores her involvement in attempts to buy Waqf property adjacent to the Kotel in the 1920s. The article brings to light a forgotten story with implications for our understanding of the role of British elites in Mandate Palestine. It demonstrates how private archives and unconventional sources can be used to illuminate the role of women in international Jewish history.

Visiting the Salomons Museum in Kent is an intimate experience. Now a training and events venue, Broomhill was purchased by the future Sir David Salomons in 1829, at a time when the right of Jews to own land was still open to question. Sir David, who became both an MP and the first Jewish Lord Mayor, was a central figure in the Jewish emancipation campaign in Britain. His nephew, the inventor Sir David Lionel Goldsmid-Stern-Salomons, turned his uncle’s Regency villa into a marvel of scientific modernity: a sprawling mansion that owes its survival to David Lionel’s daughter. In 1937, Vera Bryce Salomons gave the property to Kent County Council, stipulating that it should be used as a college, museum, scientific institute or convalescent home and that two rooms should be used exclusively as a publicly accessible “memorial hall containing the mementos now there relating to her father the late Sir David Lionel Salomons and his family.”Footnote1 The Old Library is now dedicated to the memory of Vera’s siblings, parents and grandparents. The adjoining sculpture hall contains memorabilia related to the political career of her great-uncle, alongside family portraits and other keepsakes. Additional material is stored in the Library cupboards. It includes her own postcard collection, and a unique collection of photograph albums.Footnote2 Responsibility for the whole was vested with the Board of Guardians, whose President was then Vera’s friend and cousin Hannah Cohen.Footnote3

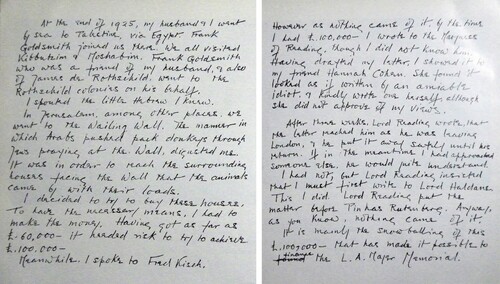

The Salomons Museum is not atypical of the British country house landscape and, at the same time, an anomaly. There are other “Jewish country house” museums like Waddesdon Manor and Upton House that possess interesting archives for the Jewish historian; Salomons is unusual because it survives as an independent foundation in a building that now serves other functions. This museum tells a very British story, but its creator lived an international life.Footnote4 Perhaps for this reason, Vera is curiously absent from Broomhill, although the display gestures towards her philanthropic activism in Israel, where she established the L.A. Mayer Museum of Islamic Art in Jerusalem, and gave discreetly but generously to other causes. So discreetly, in fact, that the most comprehensive evidence we currently have of her activity is to be found in a slender memorial volume, held at Broomhill but privately published in Jerusalem by the lawyer Arthur Bergmann.Footnote5 That volume contains a photograph of Vera, two short memorial essays in English and Hebrew, and a facsimile account of how she came to found the L.A. Mayer museum which we reproduce here ().

Figure 1. Vera Salomons' account of the founding of the L.A. Mayer Museum, made available by the L.A. Mayer Museum and reproduced from לזרה של ורה פרנסס ברייס סלעמענס.

This is an intriguing fragment both because it deals with an unknown episode, and because Vera’s behaviour does not conform to the gendered norms that conventionally defined female philanthropic activism, international diplomacy, or the Zionist movement – norms that are discussed elsewhere in this Special Issue. Vera, it seems, visited Palestine in 1925 and returned determined to buy the houses immediately opposite the Kotel. To this end, she used her knowledge of finance to raise £60,000; sought advice from the British Zionist, Colonel Frederick Kisch, and from Hannah Cohen (who also visited Palestine in the 1920s); and actively lobbied leading liberal politicians in the shape of Lord Haldane and Rufus Isaacs (by then already Marquess of Reading, having recently returned from his stint as Viceroy of India). Isaacs, who was himself a British Jew, put the matter to the Zionist activist Pinhas Rutenberg, with whom he served on the council of Rutenberg’s Palestine Electric Corporation. We wondered if a British woman – even one of Vera’s class and background – could really have been a significant independent actor, operating effectively at one remove from the Zionist movement? How might focusing the spotlight on Vera help us to understand Jewish women’s internationalism differently?

There is, of course, a literature on Jewish attempts to “buy the Kotel” and Muslim attempts to sell it – not, in fact, the Wall itself, but rather adjacent Waqf property that effectively restricted access for worship.Footnote6 Colleagues working on British Zionist activity in Mandate Palestine, whom we consulted informally, doubted either that the initiative was serious or that the account could be taken at face value. Yet details like the names of those involved were oddly convincing, the facsimile handwriting lent our source authenticity, and right at the heart of this account was something very tangible: the huge sum of £60,000.Footnote7 We started digging in printed and archival sources. The National Archives, the Central Zionist Archives, the National Library of Israel and the Weizmann Archives all drew a blank with regard either to Vera, or her initiative. Only two pieces of evidence confirmed Vera’s story. First, was a reference to her initiative in a short article exploring Vera’s relationship with her mentor, the historian of Islamic art L. A. Mayer, which mentioned “the co-operation of the Jewish Agency” and the mediating role of Judge Gad Frumkin.Footnote8 Second, was a garbled account in the memoirs of Rufus Isaacs’s daughter-in-law Eva, Marchioness of Reading, who later became Vice-President of the World Jewish Congress. Eva cites a letter from Chaim Weizmann dated December 4th 1928, regarding contributions to the Keren Hayesod: “You will be interested to hear that we have received a gift of £60,000 from a Mrs Bryce, a Jewish lady married to an Englishman of the Stern family. I think she is a niece of Lord Mitcham [surely Vera’s uncle Lord Michelham]. (This is strictly confidential). The amount in question is for the purchase of the emplacement in front of the Wailing Wall. The money is at present deposited in a Bank in Paris at the disposal of Kisch, who is responsible for the lady's interest in our affairs … ”Footnote9 Weizmann’s grip on who was who in the Anglo-Jewish aristocracy was hopelessly faulty, but we are plainly dealing with the same person and the same thing.

Elsewhere, Vera’s absence from the written record is striking. Frumkin’s autobiography details his initial discussions with Weizmann about buying the houses immediately in front of the Kotel.Footnote10 In this context, he mentions only Nathan Strauss, Fred Kisch and Henrietta Szold. The silence in Kisch’s memoir is even more glaring: there is nothing here about plans to purchase the Kotel, although Vera, Eva and Frumkin are all clear about Kisch’s involvement. The memoir does, however, include diary entries detailing disturbances between Jews and Arabs at the Kotel on Yom Kippur 1925 and 1928, as well as a full account of the 1929 riots.Footnote11

This reticence about Jewish plans to “buy the Kotel” finds an echo in the memoirs of Ronald Storrs, who served as Military Governor of Jerusalem between 1917 and 1920, and Governor of Jerusalem and Judea until 1926. Storrs is plainly aware of longstanding Jewish interest in the wall, which predated Vera’s visit. Thus he recounts a 1918 attempt by Weizmann to “acquire” the Kotel “not indeed by purchase (for Waqf property [could] not be sold), but by the lawful and frequent practice of exchange against some other acreage.”’Footnote12 Yet he has nothing to say about subsequent efforts involving either Weizmann or Vera, in 1925, or later. Nor does the material we consulted in the National Archives do much to fill in the gaps. There is an official version of Storrs’s account of Weizmann’s 1918 initiative; the record of a discussion with a certain Baron Felix de Menasoe, dated 26 August 1929; and a letter from Prince Mohamed Ali Pasha, written a week after the 1929 riots, which endorses the plan of selling the Kotel to the “Zionists,” noting that the “Mohametans and Arabs will not accept a small sum such as £10,000 or even £20,000 [but] let them give say £100,000 and I feel sure this would end the difference.”Footnote13

Here, it is worth thinking a little more deeply about the relationship between these initiatives and the Kotel riots of 1928 and 1929. In October 1925, Storrs had submitted a “Memorandum on the Wailing Wall” to the High Commissioner for Palestine in which he noted the receipt of a “petition of protest from a representative body of leading Arabs” to Weizmann’s 1918 initiative.Footnote14 He remarks that by the end of September 1918, he had “found the general delicacy of the situation so greatly increased by parallel and unauthorised negotiations, which had been simultaneously opened by the Jews without my knowledge,” that he recommended temporarily abandoning the project.Footnote15 By 1920 – when the Moslem Waqf Department undertook work to repoint some of the “upper courses” of the Wall structure – the British Mandatory Government found it necessary to repair the “two lower courses” of the Kotel itself.Footnote16 Storrs had apparently received “numerous reports” from the Zionist Commission, Rabbinate, and “other bodies,” protesting the “illegal and unnecessary action of the Waqf Authorities.”Footnote17

A potentially more explosive issue was that of “rights claimed by Jews of bringing with them chairs and benches for the performance of their religious duties”: a practice banned (at least in theory) by the Ottomans, but which the British authorities allowed.Footnote18 Importantly, from our perspective, these benches blocked the “only approach to one or more of the Magrahbi” houses that stood opposite the Kotel. Storrs notes in his Memorandum that Arab opposition to the “bench question” first occurred in April 1922, which resulted in a provisional ban on setting up benches at the Kotel.Footnote19 Tensions mounted on Yom Kippur 1925, when Jewish worshippers nonetheless set up benches and chairs.Footnote20

They spilled into violence on Yom Kippur 1928, after Jewish worshippers erected a mechitza in front of the Kotel to separate the men from the women, leaving one American woman injured. The following summer, on the Jewish fast day of Tisha B’Av (15 August 1929) members of the Zionist territorial-maximalist Revisionist party’s youth group Betar, and students from the Betar Leadership Training School staged a provocative march to the Kotel. This catalyzed a series of Arab anti-Jewish riots in Safed, Hebron, and Jerusalem, which left 133 Jews and at least 116 Arabs dead.Footnote21

The Betar demonstration was not only against the Waqf but certainly also against the Jewish Agency’s move to purchase the Kotel. For by October 1928, the initiative was well-known enough for the Betar journalist Abba Ahimeir to write a scathing article on the subject in Doar hayom (The Daily Post).Footnote22 To Ahimeir, the initiative stank of galut [exile], where everything could be bought for a price. Vera’s role in all this remains elusive. Quite clearly, the idea of purchasing the Kotel was not simply her initiative, but by raising £60,000 and making this sum available to Weizmann in December 1928, she transformed a vague idea into something more real.

Frustrated by the gaps in institutional and political archives, we wondered if the little museum in Kent could tell us more. Here we found a display case labelled “Friends and family” that included an autograph photograph of her relative Sir Moses Montefiore, a fragment of stone in a casket, and a postcard of the Kotel itself ().Footnote23 The plaque inside the casket reads: “A fragment from one of the largest stones in the West wall of the temple of Jerusalem and presented to Philip Salomons Esq. by his friend David Roberts R. A. March [1846].” The back of the postcard contains a dedication written a week before the Balfour Declaration, which makes clear that the stone was a much valued heirloom: “broken off by David Roberts R.A. when painting in the Holy Land, at the risk of his life, for the wall was guarded by Turkish sentinels – this stone was cut in half, one piece was given to Lord Pembroke (?) & the other half to his friend Sir Phillip Salomons of Brighton. The stone then passed to his son Sir David L. Salomons who gave it to his daughter Vera. October 27th 1917.” This was the eve of the second anniversary of the death of David Salomons’s only son: an event that left Vera, her father’s favourite, responsible for honouring her family name and its Jewish traditions. Above, in David Lionel’s careful Hebrew hand, we see the word: “Yerushalyim.” Finally, it is worth mentioning the evidence of a photograph album assembled by Vera’s father: here, on the same page, we find (top-left) an image of Sir Moses Montefiore looking lovingly at a portrait of his wife Judith and (top-right), a photograph of Fred Kisch’s father Herman.Footnote24 The Kisches, it transpires, were related to the Salomons (not very closely), and Herman was a Cambridge friend of David Lionel.Footnote25 There is nothing here that directly substantiates Vera’s story, but it contextualizes her motivations, activity and networks in a way that renders it compelling.

Figure 2. Family and Friends Display Case at the Salomons Museum, including a fragment of the Kotel given to the family by David Roberts, and the postcard referring to David Lionel's gift to Vera. Reproduced with the permission of Salomons Museum.

When we look at the memorabilia Vera gathered at Broomhill, we can see that her initiative was serious. She grew up in a household that regarded a fragment of the Kotel as a treasured possession: one for which she had assumed responsibility, and one to which she surely felt a deep personal and emotional connection. Jerusalem was not simply an idea for her: it was tangible. Her membership of the Jewish Historical Society of England before the war speaks to an established interest in their Jewish heritage.Footnote26 Her great uncle and aunt, David and Jeanette Salomons, had accompanied their relatives Moses and Judith Montefiore on the initial stages of their first trip to Palestine. Vera knew neither, but her father had been educated by Sir Moses’s secretary Louis Loewe. The Montefiore memorabilia she preserved at Salomons, and the more precious objects she donated to the Jewish Museum in London, speaks to their presence as a treasured memory in Vera’s family home.Footnote27 There was a lineage of international Jewish activism here – and a passion for the Holy Land – overshadowed perhaps by the scientific and secular orientation of her father, but reinforced through connections with other Jewish families like the Kisches and the Cohens. When we unpick the context for the source in this way we can see how it demonstrates the existence and impact of international Jewish networks, illuminating both their creation and their character.

So what are we to make of this story now, and how can it change the way we think about Jewish women’s international activism?

First, if we take this initiative seriously, and trace the Kotel story back to 1925 (when Vera visited) or even earlier, it becomes clear that much of the tension between Arabs and Jews at the Kotel in the late 1920s might be seen through the lens of Arab resistance to any relinquishment of their rights to the space. Indeed, Ahimeir’s article suggests that knowledge of the Jewish Agency’s attempt to purchase the Kotel was widespread. Thus both the mechitza riot of 1928 and the massacres of August 1929, may be seen in the light of ongoing tensions around this issue, rendered more tangible by Vera’s donation and by the interest apparently shown by several very influential British Jews.

Second, we need to ask why this episode has been erased from the historical narrative. Partly this may indeed reflect the gendered world of international Jewish activism and, in particular, international diplomacy. Put simply: all the official actors, in both the mainstream Zionist organizations and the British government were male, and their memoirs speak to the gendered nature of this world. Nothing suggests that Vera was interested in challenging these norms. The collection she put together at Broomhill speaks to her self-effacing quality and her desire to foreground the achievements of her male relatives. In Jerusalem, she chose to name the Museum for Islamic Art after her mentor, L. A. Mayer, rather than herself. Weizmann, indeed, notes her desire for confidentiality. Yet in retrospect she may have seen things differently. Why else did she share her account with Bergmann, and why else did he include a facsimile of the original if not to publicize what she had done, and to give that publication the stamp of authenticity? That said, the paucity of official and memoir material about Zionist attempts to purchase the Kotel during the 1920s may well reflect the desire of key players to underplay the destabilizing impact of these initiatives in Palestine.

Other articles in this Special Issue highlight the role of Jewish women in secular philanthropy, in the Zionist women’s movement, and as highly efficient administrators working within male-dominated organizations like the JDC. Vera, by contrast, discovered she could make money as well as inherit it: she consequently had the ability, the contacts and the power to be a significant independent actor. To begin with, she worked with the Zionist movement but in later life she forged her own path, dispensing the colossal sum $4 million through the David Salomons Charity, which she established in 1947, and about which remarkably little is known.Footnote28 There are parallels here with the life and work of Dorothy de Rothschild, who exerted an important formative influence on the State of Israel from her home at Waddesdon Manor, long after the death of her husband in 1957.Footnote29 Both women operated independently through discreetly managed private foundations, named after their more prominent male relatives. To understand more about such women, we need to look beyond the obvious places associated with governments, quasi-political organizations and (male) diplomats. We need to look in the private spaces from which they operated, and to consider sources that may look and feel very different from those we had expected to find.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are due to Chris Jones, Luisa Levi d’Ancona Modena, Amit Levy, and the staff at the L. A. Mayer Museum for their help in accessing - and pointing us towards - the material in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abigail Green

Abigail Green is Professor of Modern European History at the University of Oxford, and a Tutorial Fellow at Brasenose College. She is the author of Moses Montefiore: Jewish Liberator, Imperial Hero (2010), and of numerous articles and edited collections, most recently, with Simon Levis-Sullam, Jews, Liberalism, Antisemitism: a Global History (2020). She is currently writing an international history of Jewish liberal activism, and leading a collaborative research project on Jewish Country Houses.

Peter Bergamin

Peter Bergamin is Lecturer in Oriental Studies at Mansfield College, University of Oxford and Research Fellow of the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies. He is the author of The Making of the Israeli Far-Right: Abba Ahimeir and Zionist Ideology (2020). His current research looks at Britain’s withdrawal from the Palestine Mandate.

Notes

1 Deed of Trust made between Vera Frances Salomons of 31 Rue Vineuse Paris and the Board of Guardians and Trustees for the Relief of Jewish Poor. November 8, 1937. Made available by the Salomons administrators. On Vera’s family, see Parkes, Three David Salomons.

2 For an overview, see Brown, David Salomons House. On the postcard collection, see Auckland, “The Postcard Albums of Vera Salomons.” On the photographic history of Broomhill, see Klein, “The Young Photographer.”

3 Klein, “Hannah Floretta Cohen.”

4 There is almost no work on Vera Salomons. See, however, Wawryzn, Attempts at a Biography.

5 לזרה שׂל ורה פרנסס ברייס סלעמענס.

6 See for example Mazza, “The Attempted Sale of the Western Wall by Cemal Pasha”; Kramer, נסיונת יהודים לרכוש נכסי וקף באזור הכותל המערבי בשלהי התקופה האוסמאנית , 1887-1916; and Shiller and Barkai, הכותל המערבי: כתב עת לידיעת ארץ ישראל. We are indebted to Yisrael Medad for leading us to the last source.

7 A comparison with MS letters from Vera held at the Salomons Museum in Kent confirmed the authenticity of the handwriting.

8 Moshe Hananel, 1946 מסע בספר הטלפונים המנדטים, 203–5.

9 Isaacs, The Memoirs of Eva, Marchioness, 117. With thanks to Tom Stammers.

10 For more details, see Frumkin, דרך שופט בירושלים, 276–9.

11 Kisch, Palestine Diary, 206, 211, 245, 253–90, etc.

12 Storrs, Orientations, 347.

13 See TNA FO 371/13746/31 and 34, and TNA FO 371/13746/43. See also, inter alia, TNA CO 733/98 and CO 733/162/4 for documentation on the Kotel from 1925 to 1929.

14 TNA CO 733/98/795-6.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid., 796.

19 Ibid., 797.

20 Ibid.

21 On the 1929 riots, see Cohen, Year Zero of the Arab-Israeli Conflict and Shindler, Rise of the Israeli Right, 88–93.

22 Ahimeir, “מפנקסו של פשיסטן.” On Ahimeir, see Bergamin, Rise of the Israeli Far-Right.

23 SM: Montefiore photograph, DSH.M.00126; fragment of stone: DSH.M.00077; postcard: DSH.M.00823.

24 SM DSH.M.00510: 27. Our thanks to Michele Klein for drawing our attention to this page, and to Cyril Grange for providing us with a genealogy of the Kisch family.

25 Our thanks to Chris Jones at Salomons for spotting the photograph of them together.

26 “List of Members,” Transactions.

27 Her donations to the Jewish Museum include photographs of Sir Moses and of Lady Judith Montefiore, and a gold locket with rubies and diamonds carrying their photographs. Our thanks to Tom Stammers for this information.

28 לזרה שׂל ורה פרנסס ברייס סלעמענס.

29 Shalvi, “Mathilde Dorothy de Rothschild.”

References

- Ahimeir, Abba. “מפנקסו של פשיסטן.” Doar HaYom, October 8, 1928.

- Auckland, S. Caroline. “The Postcard Albums of Vera Salomons; Exploring Collected Fragmented Written Conversations and Decoding the Family Archive, a Record of Social Practice.” MA in Victorian Studies dissertation. London: Birkbeck College, 2016.

- Bergamin, Peter. The Rise of the Israeli Far-Right: Abba Ahimeir and Zionist Ideology. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2020.

- Brown, M. D. David Salomons House. Catalogue of Mementos. Printed privately, 1968.

- Central Zionist Archives (CZA), Jerusalem

- Cohen, Hillel. Year Zero of the Israeli-Arab Conflict 1929. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2015.

- Frumkin, Gad. דרך שופט בירולים. Tel Aviv: Dvir Co. Ltd., 1954.

- Hananel, Moshe. 1946 מסע בספר הטלפונים המנדטים. Tel Aviv: Eretz Hatzvi, 2007.

- Isaacs, Eva. For the Record: The Memoirs of Eva, Marchioness of Reading. London: Hutchinson, 1973.

- Kent & Sussex Courier, 13 September 1929.

- Kisch, Frederick H. Palestine Diary. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1938.

- Klein, Michele. “Hannah Floretta Cohen.” Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, June 23, 2021. Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/cohen-hannah-floretta.

- Klein, Michele. “The Young Photographer at Broomhill.” https://jch.history.ox.ac.uk/article/young-photographer-broomhill.

- Kramer, Gabi. “נסיונת יהודים לרכוש נכסי וקף באזור הכותל המערבי בשלהי התקופה האוסמאנית.1887–1916.” Jama’ah 2, no. 2 (1998): 29–45.

- “List of Members.” Transactions (Jewish Historical Society of England) 7 (1911–14): 325.

- The National Archives (TNA), Kew

- Mazza, Roberto. “The Deal of the Century? The Attempted Sale of the Western Wall by Cemal Pasha in 1916.” Middle Eastern Studies 57, no. 5 (2021): 696–711.

- Parkes, James. The Story of Three David Salomons at Broomhill. Printed privately, 1950.

- Salomons Museum (SM), Tunbridge Wells

- Shalvi, Alice. “Mathilde Dorothy de Rothschild.” Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, December 31, 1999. Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/rothschild-mathilde-dorothy-de.

- Shiller, Ari, and Gabriel Barkai, eds. הכותל המערבי: כתב עת לידיעת ארץ ישראל. Jerusalem: Ariel, 2007.

- Shindler, Colin. The Rise of the Israeli Right: From Odessa to Hebron. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Storrs, Ronald. Orientations. London: Nicholson and Watson, 1945.

- Wawryzn, Heidemarie. “Attempts.” In Attempts at a Biography of Vera Salomons (Postgraduate Research Paper). Grin, 2016. Nicholson and Watson.

- לזרה שׂל ורה פרנסס ברייס סלעמענס. Jerusalem: Privately published, 1970.