ABSTRACT

Ecosystem restoration remains high on development agendas worldwide. In the Sahel, including Senegal, knowledge gaps remain on how the underlying policy and regulations for rights and ownership influence farmers’ incentives for upscaling land restoration. We contribute to filling these gaps by i) analysing agroforestry related policy and regulations, and ii) assessing key stakeholders (foresters, animators, and farmers) perceptions in Kaffrine, Kaolack and Fatick regions using semi-structured interviews. The results show that tree rights and use procedures are determined by the Forestry Code and vary according to the status and location of the tree. However, the Forestry Code was found to be inappropriate for managing agroforestry systems where farmer managed natural regeneration (FMNR) is practiced, hence creating barriers to its adoption. Contrasting perceptions and potential solutions emerged. While the field animators and farmers find the tree use procedures burdensome and constraining for the practice of FMNR, most foresters find them not burdensome and appropriate for environmental protection. As solutions, animators and foresters suggest farmers’ sensitization, capacity building, and rewards, whereas the farmers call for an easing of tree use procedures and a reduction of taxes and permit fees. These results suggest farmer-centric and inclusive policy reform of tree rights in Senegal.

1. Introduction

The United Nations decreed 2020–2030 the decade of ecosystem restoration. In Africa, key initiatives to achieve large-scale land restoration include the African Forest Landscape Restoration (AFR100) aiming to restore over 100 million hectares of degraded land across the continent, and the Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel (GGW) with an accelerator strategy that has the ambition to restore 100 million hectares, create 10 million green jobs in rural areas and store 250 million tonnes of CO2 by 2030. For these restoration initiatives to reach their targets, and sustainably transform the socioecological systems, the engagement of grassroot parties and actors, namely, the farmers, is fundamental. A review of land restoration initiatives in Africa by 2021 has stressed local actors’ participation as essential for success (Mansourian and Berrahmouni Citation2021). Moreover, an enabling policy and regulatory environment that empowers local actors is critical for meaningful local participation, and sustainability of the achievements (Bernard et al. Citation2019).

Ground implementation of these restoration initiatives revolves around proven restoration practices such as agroforestry, i.e., the integration of trees into farming systems for their numerous livelihoods, socioecological and economic benefits (Muthee et al. Citation2022; Garrity Citation2012). Agroforestry is known to help restore degraded forest and agro-pastoral systems (Ba et al. Citation2018; Diallo et al. Citation2019; Bayala et al. Citation2020; Suharti et al. Citation2022), generate income for farmers (Binam et al. Citation2017), address food security and various adverse effects of climate change (Bayala et al. Citation2014; Mbow et al. Citation2014), preserve biodiversity in farming systems (Leakey Citation1999; Zomer et al. Citation2014). One of the key agroforestry practices implemented successfully and at a low cost in the Sahel, is Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR) also known as Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR). FMNR consists of farmers selecting, pruning, and nurturing the resprouting tree and shrub stumps that regenerate naturally from the in-situ germplasm, including the roots and seed stock present in the farmland (Lohbeck et al. Citation2020). Compared to tree planting, FMNR presents technical advantages: it is cheaper, accessible to farmers including those with fewer financial resources, requires limited labour/input, and presents higher tree survival rates because it is adapted to drier environmental conditions (Reij and Garrity Citation2016; Chomba et al. Citation2020).

Yet, in sub-Saharan Africa, including in Senegal, the existing literature points to inappropriate agroforestry-related policy and regulations, rooted in colonial forestry path dependencies, that limit farmers’ incentives to invest in agroforestry development (Elbow and Rochegude Citation1991; Ribot Citation2001; Bandiaky-Badji Citation2011; Yatich et al. Citation2016; Faye et al. Citation2018). Moreover, unfavourable national policy contexts are a major challenge to the wider adoption of agroforestry, and its contribution to sustainable development (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations-FAO Citation2013; de Foresta Citation2013). Agroforestry also lacks its own policy framework, institutional niche, and development strategies and plans as well as financing mechanisms (Bernard et al. Citation2019; Muthee et al. Citation2022). Consequently, the rules and regulations governing land restoration and agroforestry are diluted within the existing sectoral ministerial policies (e.g., forestry, agriculture, livestock, and water). This leads to coordination challenges among these ministries as well as technical and financing issues (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations-FAO Citation2013; Bernard et al. Citation2019).

In addition, unsecure and unclear status of land and tree resources in agricultural areas coupled with underlying issues of benefit sharing, mismatches between state legal statutory ownership and farmers’ legitimate entitlement to the tree resources have limited the potential of agroforestry (Alinon and Kalinganire Citation2016; Bernard et al. Citation2019; Ndlovu and Borrass Citation2021). In Senegal, like many West African Sahelian countries, trees on farms are part of national assets and subjected to specific regulations for their use, regardless of who owns the farm or grows the trees. Given the regulations, the following questions emerge: Who should own the trees on farms? Can those that have grown the trees use them when needed? Under which conditions?

Literature about the trees on farms worldwide is rich and diverse. For example, Tsonkova et al. (Citation2018) found that the legal framework and administrative constraints were the major obstacle to agroforestry development in Germany. In Australia Fleming et al. (Citation2019) have identified farmers’ perceptions rooted in social norms and values as the main barriers. In Kenya, Dewees (Citation1995) has shown that nurturing trees on farm were a customary practice, and that governmental land policy reforms presented mixed impacts on peoples’ land and tree tenure security, and their incentives to expand agroforestry on their property. However, in the Sahel, particularly in Senegal where plural politico-legal logics govern land and tree resources, discussions on rights over trees on farm, their use procedures, and the implications for incentivising the uptake of land restoration and agroforestry practices are scarce. Literature that does exist misses a systematic analysis of these critical aspects, specifically from the point of view of the major players. Thus, our study aims to fill this gap by assessing the perception of government foresters, field animators (local extension staff), and farmers regarding the burdensomeness of tree use regulations, and the implications for the adoption of FMNR by farmers, a major agroforestry practice in Senegal. First, we analysed the legal and regulatory frameworks governing the practice of land restoration and agroforestry in the country. We also assessed how these governance instruments, such as the Forestry Code, are implemented in the management of trees on farm, and the extent to which they support farmers’ investment in agroforestry. Second, through farmers, foresters, and field animators’ perceptions, we analysed the extent to which the tree rights and use regulations are burdensome, and what suggestions were made by these stakeholders to address the bottlenecks. We hypothesize that clear and coherent agroforestry policy and regulations as well as simplified tree use procedures would lead to greater farmers’ control over land restoration benefits and thus accelerate the scaling-up of FMNR and agroforestry in Senegal. Finally, we used the Institutions, Information, Ideas, Interests (4Is) framework (Brockhaus and Angelsen Citation2012) to discuss the study results, explore FMNR and agroforestry institutional pathways within the broader sociohistorical context of the Sahel.

1.1. Policy landscape for land restoration, agroforestry and FMNR practices in Senegal

Overall, Senegal’s national policies recognize the merits of agroforestry, FMNR and other soil and water conservation practices for the country’s development, its national/international, climate and ecosystem restoration commitments. These commitments are implemented through various sectorial policy frameworks, letters, strategy, and plans such as the ‘Green’ Senegal Emergent Program (PSE) which guides the country’s environmental policy including land restoration targets, climate change adaptation and mitigation, the National Forest Policy 2005–2025 which suggests agroforestry practices for agro-sylvo-pastoral development, food security, and biodiversity protection. Specifically, FMNR and other sustainable land restoration and water management practices are central to the country’s Land Degradation Neutrality by 2035 strategy, the National Adaptation Program of Action, and the Senegalese Agriculture Recovery and Acceleration Program 2019–2023.

However, certain constraints characterize the policy landscape: the absence of a specific agroforestry and/or FMNR development policy framework, unclear distribution of rights over the restored ecosystems, institutional and inter-ministerial/sectoral coordination challenges. In addition, the ways in which these merits of agroforestry practices are translated on the ground and upheld by the state technical services will determine the policies’ effectiveness. Moreover, the policy implementation depends heavily on the community, and access to knowledge. Land and tree tenure rights and benefits are also instrumental to ensure meaningful impact.

Land tenure systems are a critical component to consider for motivating uptake as they influence farmers’ opportunities to undertake and benefit from agroforestry and land restoration practices. Land governance in Senegal underwent three important tenure moments (before, during and after colonization), each characterized by a particular land tenure system. Before colonization, land access, and management was vested in customary authorities according to customary law. During colonization, land tenure embodied by the civil code promulgated by the decree of 15 November 1930, did not recognize the pre-existing customs and traditions of the colonized population. After independence, the law on the national domain (law 64–46 of 17 June 1964) was issued and enforced. This law created a national domain that covers 95% of the national lands and vested the exclusive land management and registration rights in the State, and in the decentralized authorities (from 1972 due to decentralization). Under this law, people using land in the national domain may continue to occupy and exploit those lands unless the competent decentralized bodies decide to withdraw those lands because of their undervaluing, or for reasons of general interest. Furthermore, this law subdivided the national domain into four zones: urban, classified, pioneer and local zones. The local zones are where rural communities undertake their housing, livelihoods, agriculture, agroforestry, and other land restoration practices. These land and tree tenure changes bear implications for the security of farmers’ rights, investments, and long-term benefits from agroforestry endeavour.

If the practice of land restoration, agroforestry and FMNR are encouraged in policies, the management, use, and benefit sharing over the restored ecosystems and resources is contingent on diverse factors. The Forestry Code of 2018 and its application decree of 2019 constitute the mainstream framework for the management of trees in the country. The code recognizes the private ownership and decentralized management of forest plantations created by individuals, but without granting them ownership of the land which is still held by the state (as per the national domain law of 1964). This Forestry Code went through various reforms: the 1974 revision aimed to reduce the constraining nature, while the 1993 revision attempted to promote the participation of local populations in the protection and restoration of forest resources. The 1998 and 2013 revision brought in the principles of decentralized natural resource management. Under the 2018 Forestry Code, permit requirements were reviewed, and the penalties for offenses have become more severe (see Title II). The results section elaborates more on the modalities of enforcement of the Forestry Code and similar regulations to the management of agroforestry parklands.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection and analysis

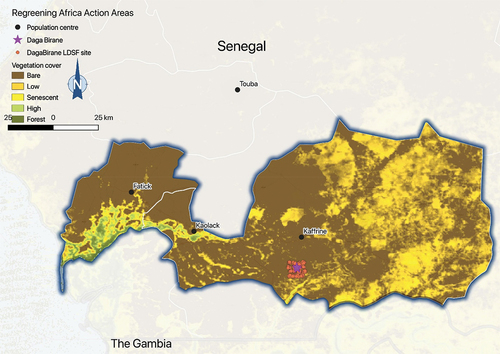

We conducted field data collection between April and May 2022 in the regions of Fatick, Kaolack and Kaffrine located in the groundnut basin in Senegal (). The regions are characterised by a Sudano-sahelian climate, an average annual rainfall varying between 520 mm and 680 mm/year and a flat land with essentially tropical ferruginous, leached or unleached, hydromorphic and halomorphic soils. We selected those locations because of their long-standing experience of FMNR and agroforestry which allows a better understanding of the policy effects on the parties engaged in these land restoration practices. In addition, these were also intervention sites of Regreening Africa, a land restoration project.

Figure 1. Map of the study sites of Kaffrine, Kaolack and Fatick in Senegal, West Africa.

We conducted semi-structured interviews tailored to our three informant groups: the state forest agents here called the foresters, the field animators (local extension agents), and the farmers. We recruited the interviewees using a nonprobability and purposive sampling approach that enable the selection of interviewees according to a defined set of criteria pertinent for the study at hand and a flexible number of informants of 16 to 40 to reach data saturation of the mainstream themes (Guest et al. Citation2006; Hagaman and Wutich Citation2017). We obtained responses from a total of 114 actors among which there were 45 animators, 45 FMNR practicing farmers and 24 foresters. For the foresters, we invited a response from local and sub-national forestry agency for their formal role in enforcing and overseeing environmental laws on the ground. The field animators were chosen for their involvement in extension services delivery to local communities within the Regreening Africa project. We recruited the farmers according to their location within the study sites, their experience in practicing FMNR, agroforestry, and/or land restoration, and their role as lead farmers in their community.

With the foresters, we stressed particularly the formal procedures, laws, and regulations that they apply in their duty to the use, pruning and removal of trees under different settings, and their opinion on the opportunity for FMNR policy reform, for example through a decree. Moreover, with all the interviewees, we assessed their perceptions of the burdensomeness of current regulations, the implications of the procedures for farmers’ incentives to practice FMNR, and finally the suggestions for improvement in the law.

The variable burdensomeness includes the duration to follow the procedures and receive the permit for pruning or felling the tree, the number of administrative steps, and parties involved in the process. The assessment includes indigenous trees species on farm, either planted or established through FMNR. The interviewees gave various explanations to justify their responses on the burdensomeness of the tree use regulations. From those responses emerged different categories of explanations such as, for example, the length (duration, distance) and the cost of the permit. In addition to this inductive data analysis strategy, we conducted a descriptive analysis based on results presented in a spreadsheet.

We anonymized the informant’s name and quote them using ST followed by the interviewee’s number for the foresters (ST1 for example), and Ani for the animators (Ani3 for example). Of the forester respondents, 54% had 5–19 years professional experience, while 8% had more than 20 years. As for the field animators, 65% had less than five years of work experience in the field and 2% between 15 and 20 years’ experience. The farmers were 95% male and 5% female due to a male dominant land tenure and ownership associated with the practice of FMNR. The average age of the farmers was 50 years old with a minimum age of 33 and maximum age of 70. Farmers experience in practicing FMNR on their farms shows an average of eight years, with a minimum of one year and maximum of 50 years.

We complemented this survey with an analysis of the current Forestry Code, and related decree (décret d’application) to better understand the governance of trees on farms in the country. Specifically, we disentangled the key articles that the forester respondents quoted as guiding their daily enforcement of the law in their duty. These key articles of the Forestry Code are reported in English in the article, with the original French in the Appendix.

We presented the study results in two events: a national workshop in Dakar NaN Invalid Date NaN, on Inclusive and Evidence-Based Approaches to Advancing Land Restoration in Senegal; and a cross-country policy learning event in Niamey 12–NaN Invalid Date on the Niger FMNR presidential decree. Through these events, we collected feedback from governmental, NGO, and research community participants that helped as triangulation mechanisms to ascertain and improve the quality of the information presented.

To further elaborate on our results, we chose the 4Is framework (Brockhaus and Angelsen Citation2012): Institutions (as rules, institutional path-dependencies, or stickiness), Interests (as potential material advantages), Ideas (as policy discourses, underlying ideologies, or beliefs) and Information (as data, knowledge, and their construction and use). The interaction between these 4Is provided a strong lens to identify and conceptualise the barriers and opportunities for transformational change in tree-on-farm policy arenas. In our case, the 4Is framework helped us i) better structure and situate our results in the broader historical and socio-political context of Senegal and the Sahel, and ii) unearth the underlying forces explaining our results, their origin, and mechanisms of production and reproduction.

3. Results

3.1. Tree rights and use procedures according to the law and the law enforcement officers

In Senegal, key legal and regulatory provisions guide tree rights and use: the Forestry Code (FC) and its application decree (Law 2018–25 of 12 November 2018 on the Forestry Code (FC), the Decree No. 2019–110 of 16 January 2019 on the application of the Forestry Code) and the Decentralization law (Law No. 2013–10 of 28 December 2013 on the General Code of Local Government in Senegal).

Use rights (le droit d’usage) are recognized for populations whose livelihoods depend on the ecosystems under consideration, but within the limits and conditions set by the Water and Forestry Services (WFS) (ref. article 33).

The use rights cover various forest products specified in the Article 29 of the FC:

In the forests of the national domain, the local populations have the following use rights, the collection of dead wood and straw, the harvesting of fruits, leaves, roots, bark, gums, resins and honey for food or medicinal purposes, the grazing of livestock and the pruning of fodder species, the cutting of multipurpose construction wood, the use of sacred woodlots for cultural purposes. These use rights do not entail any right to dispose of the land areas.

However, ‘the products acquired by virtue of the use right are strictly limited to the personal and family needs of the users, may only circulate outside the beneficiary’s land area after authorization from the Water and Forestry Service (WFS)’ Article 32 FC.

There are 11 fully protected tree species and 17 partially protected species in Senegal according to Article 51 of the Decree No. 2019–110 of 16 January 2019 implementing the 2018 Forestry Code (FC). The conditions for the use of these species are specified in Article 50 of the decree:

The felling, uprooting, mutilation and lopping of fully protected species are formally prohibited, except in cases of derogation granted by the WFS for scientific or medicinal reasons. Partially protected species may not be felled, lopped, or uprooted without prior authorization from the WFS.

During fieldwork, when asked what the procedures are for exploiting the trees on farm, the forestry law enforcement officers gave different responses, varying from one interviewee to another, and according to the tree specificities: the origin of the tree (planted or naturally regenerated with or without assistance), its species (local or exotic), its status (protected or not), its targeted product (woody or non-woody, pruned or uprooted), its use (household consumption or for commercial purposes) and its final destination (local market of product’s origin or transported elsewhere). The forestry officers mentioned that their understanding and enforcement of the procedures are based on the following key articles of the 2018 Forestry Code and its implementing Decree No. 2019–110 of 16 January 2019

Prior authorization from the concerned commune (due to the decentralization policy) is required in reference to the Article 20 of the FC (concerning the exploitation of trees on communal land outside a private domain) and Article 13 (focusing on the exploitation of trees on local authorities’ land): ‘The exploitation and/or valorisation of forest products and services in forests under the jurisdiction of local authorities is subject to prior authorization [.] of the concerned Municipal Council. The exploitation permit is issued by the WFS’. The prior authorization of the municipality is indicative, as the actual permit issuance depends on the WFS approval, after their technical assessment.

The requirement of payment for a permit and taxes (redevance forestière) prior to the exploitation of a tree in the forest estate takes root in the Article 12 of the FC: ‘The exploitation of any forest resource in the forest estate is subject to the prior payment of taxes and royalties under the conditions and forms defined by decree with the exception of private forests and the use right’. Furthermore, the Decree No. 2001–217 of 13 March 2001 establishing taxes and fees for forest exploitation details the rates of the taxes and fees according to the characteristics, origin, and destination of the tree.

For example, quoting the above articles 20 and 12 of the FC, ST 2 of Kaolack, with 5–10 years of professional experience, explains that the procedures for felling trees on fields are subject to the authorization of the municipal council of the commune, which issues a preauthorization to cut them. Afterward, the WFS may issue the actual permit after a technical assessment, and the payment of taxes by the farmer applicant.

Furthermore, for ST 10 in Fatick, Male, 15–20 years of experience, the procedures are as follows: 1) Obtaining pre-authorization for felling the tree issued by the municipal council on a handwritten request addressed to the mayor of the commune by the applicant; 2) Introducing the pre-authorization to the WFS (the applicant goes to the Brigade Chief of the WFS); 3) Assessment by the representative of the WFS (the WFS officer goes to the field to carry out an assessment sanctioned by a written document (le constat). This document reports the compliance for awarding the felling permit including, what tree species it is, whether the tree is alive or dead, for what purpose the tree is being exploited, is it inside the fields, etc.; 4) Issuance of a felling permit (if the conditions are met, the applicant must submit the file including the prior felling permit and the forestry officer’s report to the WFS. The Head of the Sector assesses and forwards the application to the Forestry Inspectorate. The inspector may authorize the felling by issuing a definitive authorization with limited time validity. 5) This authorization is given to the applicant who must first pay a permit fee and felling taxes to the cashier before cutting the tree.

However, the cutting of trees on private land are freely authorized after the justification of private ownership, a management plan and preauthorization by the municipal council, the endorsement and delivery of the felling permit by the representative of the WFS without payment of taxes and fees, argued ST 20 in Kaolack male, with more than 20 years of professional experience, and quoting the Article 19 of the FC:

The collection and cutting of forest products, when carried out by the natural or legal person who owns the plantation, are free of charge. However, the exploitation of these products shall be carried out in accordance with the prescriptions of the management plan or simple management plan of the forest. These same provisions are applicable to owners of a field or a forestry operator who wish to carry out activities of valorisation of forest services or cutting, delimbing, felling and debarking of planted trees and/or resulting from natural regeneration, whether assisted or not, located within their domain.

Specifically, concerning trees from FMNR, different versions of the regulation are stated by the forestry law enforcement officers. For a minority such as ST20 in Kaolack, with more than 20 years’ experience the same five-step procedures apply to FMNR trees including the payment of permit fees and taxes. However, for most of the foresters’ respondents, such as ST 24, 5–10 years of experience, quoting the Article 19 of the FC, the felling of FMNR trees is free of charge, but should always follow the opinion of the municipal council and the technical assessment of the WFS. For ST5, Fatick, with more than 20 years’ experience, quoting the articles 13, 19 and 20 of the FC, stated that a free permit delivered by the WFS, following prior authorization by the municipal council is required for the operation of FMNR trees. For that officer, it is necessary that the WFS register and monitor FMNR practicing farmers, the number of their trees so to facilitate this free permit process whenever needed. Bringing some more nuances, ST12 from Kaolack, 5–10 years’ experience citing the same articles noted that the felling of FMNR trees or those planted on farm do not require any authorization because these trees belong to the individual or legal entity that nurtured them; giving that the operations are done in accordance with the prescriptions of a simple/management plan and do not conflict with the principles of environmental protection.

On tree use for value-chain development, the following are required according to the prescriptions of the following the Article 32, 21 and 5 of the FC: a permission by the WFS, a professional card, a permit of deposit and circulation to be able to convey the tree products from their area of collection, including the products acquired from regular logging, and based on the use right. From Article 32:’ ‘The products acquired by virtue of the use right, strictly limited to the personal and family needs of the users, can only circulate outside the beneficiary’s territory after authorisation from the WFS’.

Similarly, the Article 21 reiterates the need for a permit of circulation which specifies the origin of the products, their nature, quantity, and the regularity of the operation. Its issuance is free of charge (Art. 14, Decree implementing the FC). However, ‘issuance may only be refused if the exploitation does not comply with the provisions of Article 19 of this Code or if the operator has not paid the royalty or the fees from the sale of timber by auction’. Article 21 FC.

For Article 5 of the FC, ‘the exploitation of non-quota products requires a logging permit, while the exploitation of quota products requires a professional forestry operator’s card for organizations or a local producer’s card for members of cooperative in managed forests.’

Depending on the nature and severity of the offence caused, articles 52 to 55, and 61 of the FC provide, among other sanctions, the payment of a fine ranging from 500,000 FCFA to 5 million FCFA (USD 829 to 8 291) and a prison sentence of 6 months to eight years.

From the above, gaps and questions arise: first, the management plan requirement expressed in the article 19 above applies to forest formations of more than 50 ha, and the simple management plan to those between 05 and 50 hectares according to the Art. 1 of the Decree No. 2019–110 of 16 January 2019 implementing the FC. However, the decree does not specify what happens to forest formations of less than 5 ha. For a field of less than 5 ha, is a management plan required or not required? How will the provision of this article 19 on free permits be applied to those farms of less than 5 ha, and not covered by a management plan? Moreover, in practice, there are few family farms whose objective is to produce forest or woody plants, and even fewer that have a management plan; hence, the need to adapt some of these law provisions to the local context of smallholder agroforestry producers.

Second, the provisions of Article 20 on prior consultation of the municipal council to which ST2 refers do not concern private estates including individual crop farms, but land outside private estates: Are fields considered as a private domain? If yes, would this article 20 be enforced on the use of trees in the farms? Similarly in article 12 often quoted on permit requirements, are fields considered private domain or forest? If so, this article 12 would not apply to farms either! There is a need to define what is a farm, which is different from a forest, and the trees on farms which are different from trees in the forest.

Third, the five key steps outlined above (rooted in articles 13 and 20 of the FC) concern the felling of a tree in the protected area of local municipalities and not on individual farms. The question arises whether the field of small producers is part of the protected domain of the local municipalities or a private domain? If the latter, these provisions would not fully apply.

Finally, what are the implications of these requirements for women groups or other CBOs who collect Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) in their village and would like to sell them on neighbouring markets?

3.2 Assessing the burdensomeness of tree uses procedures: actors’ perceptions

This section assesses the perceptions across the three categories of actors (the foresters, the field animators, and the farmers) on the burdensomeness of tree use procedures ().

Figure 2. Foresters, animators, and farmers’ varied perceptions of the burdensomeness of tree use procedures.

Regarding the foresters’ (n = 24) perception on the burdensomeness of tree use procedures, the bulk of respondents (46%) find the procedures not burdensome, while 33% judge them moderately burdensome and 21% too burdensome.

The foresters offered different explanations for their responses on the burdensomeness of the procedures. About 29% of the respondents found the regulations appropriate for environmental protection as they may reduce abusive tree cutting according to ST6 from Fatick. For those who found the procedures burdensome, 25% of their responses are associated with lengthy and time-consuming process due to long travel distance for the farmer. For ST9 ‘sometimes the waiting time is very, very long and the farmer believes that I have not taken his request to the next level and keeps reminding me every day. When tired of waiting he gets discouraged and may cut the tree behind my back.’ Likewise, ST24 adds ‘we observed that the rural population no longer wishes to have trees in their farming or inhabitation area due to the cumbersome procedures for cutting or using the nurtured tree for their needs.’ Specifically, 8% mentioned the cost as an explanation of the cumbersomeness. For 4%, the process is considered burdensome as it discourages farmers from practicing FMNR.

For another 4% of foresters, the procedures are burdensome because the municipal agents are slow in delivering the required preauthorization. For example, ST14 from Kaolack explains: ‘the decision of the municipal council is difficult to get because the council has to meet first’. Therefore, for ST4 from Fatick “the slowness is only noticed at the level of municipal authorities, who have difficulties in establishing prior authorizations. Otherwise, the procedure is not that burdensome.’

Regarding the field animators, a majority (67%) of the respondents found the tree use procedures too burdensome, whereas 29% found them not burdensome and 4%, judged them as moderately burdensome. The field animators used different logic to explain their perceptions. For a majority (51%) the procedures are burdensome because they are long and time-consuming. For instance, for Ani28 in Kaffrine, the procedures are burdensome:

because the distance to the district headquarters where you must get the permit with the Water and Forestry department is 75 km, the road is unpaved and damaged. Also, anyone who wants to cut a tree must pay taxes that can be at times expensive for the farmers.

Ani19 Fatick gives further details:

It is difficult for farmers to obtain a tree cutting permit. You must go and collect the permit application form, then fill it in, go to the village chief to get their approval, go to the town hall to get a stamp and signature, then go to the WFS. Afterwards, the forestry officer must come to the farm and make a report, and then he will send the decision to the forestry sector chief for a final decision, after which the farmer could pay the taxes and obtain the permit if a positive decision is served.

The decision could be negative in which case, the farmer would be denied a permit.

An additional 24% emphasizes the high related cost: Ani44 in Kaffrine ‘Sometimes the cost they charge for a permit is very expensive given the farmers’ financial conditions here. If it could be made easier it would be better. The amount of tax to be paid for cutting trees should be reduced.’ The municipality’s slowness in the procedures was highlighted by 4% among which 2% specifically mention the literacy requirement to fill the permit forms while many farmers may not be literate. Moreover, 13% recognize the burdensomeness as a good solution to environmental degradation:

the tree use procedure is not cumbersome given the importance of environmental protection. I really appreciate it because if the regulations are not strict, the environment will be destroyed and the desert will advance, resulting in scarce rainfall, low yields, and extinction of certain animal species. Ani29

However, 9% associate the burdensomeness of procedures with farmer’s disincentive to invest into the practice of FMNR. Among the remaining animators, 20% argue that the procedures are not burdensome because they follow the law and that the permit can be obtained without duress for those who know and understand the Forestry Code.

Finally, regarding the farmers’ perception of the burdensomeness of tree use procedures, 80% of the farmers’ respondents found the tree use procedures too burdensome, compared to 13% who found them not burdensome and 7% judge them moderately burdensome.

The farmers provided various arguments to support their responses. For 62% of the farmers, the procedures are burdensome because of their length, the time and distance involved. Farmer 35, male, 54 years old, and five years of practising FMNR explained that the procedures are:

too burdensome because there should be the possibility of us using the FMNR trees we have grown after few years of labour in a reasonable way without abusing the tree, for example cutting only the branches without felling the tree. I have submitted a request to the WFS to cut my FMNR trees in my field to solve an urgent problem. But for more than three months I haven’t yet received a response.

Two other categories of explanation were argued by just over 13%: the procedures are burdensome as they are costly and constrain the practice of FMNR; and the procedures are strict but good for environmental protection.

3.3. Assessing the conduciveness of current regulations for scaling up FMNR: actors’ perceptions

In this section, we analyse the responses of the field animators and farmers on whether current tree use procedures are conducive for wider practice and scaling of FMNR in the country ().

Figure 3. Animators and farmers perceptions of the conduciveness of tree use procedures for scaling FMNR.

For 61% of the field animators, the procedure for using trees on farms can discourage farmers from practicing FMNR because of complications the farmers may encounter when the FMNR trees mature and need to be harvested for multiple products including wood. Ani20 from Kaolack shares their experience:

When we manage to convince a farmer to do FMNR by telling him that he can benefit from the fuelwood from his FMNR tree, and this same farmer experiences difficulties in getting access to the trees in his own farm, he may be discouraged and decide to stop practicing FMNR.

Likewise, for Ani40, in Fatick ‘farmers tell us that they want to practice FMNR, but they are discouraged by the fact that it would be difficult for them to obtain a tree cutting permit when the trees mature’. However, 39% think that the procedures do not discourage farmers from practicing FMNR because of numerous other advantages of FMNR beyond the wood. Ani21 Fatick explains:

Even if the farmer finds it difficult to cut down the FMNR trees in his own field, he should not be discouraged. Because the trees remain in his field, he can benefit from the trees’ shade, he can feed his animals with the fruits, and the leaves can be used to fertilize the soil.

Ani44, Kaffrine ‘In our municipality of Mabo, we have no problem cutting our FMNR trees. We must call and inform the WFS officer, and he give us the green light to proceed’.

Concerning the farmers, 68% of them argued that current tree use procedures can discourage them from practicing FMNR. For example, Farmer 28, from Kaolack, 70 years old, five years of practicing FMNR explains ‘there are farmers in my village who face this problem. They want to plant millet, but they can’t get a permit to prune the tree branches in their field if the branches are left as they are, they will harbour predators and crop destroyers like birds.’ Another farmer17, male from Kaffrine, 52-year-old, 15 years of practicing FMNR, adds: ‘farmers have limited financial resources. If they are still asked to pay taxes for a tree cutting permit, they may get discouraged from practicing FMNR’. As a result, farmer 42, female from Kaffrine, 42 years old, four years of practicing FMNR, explains: ‘there are farmers in my village who stopped practicing FMNR in their fields because when the trees grow, they will have difficulty obtaining a cutting permit’.

However, 32% of farmers reported that the procedures do not discourage them from practicing FMNR because the trees have benefits beyond the wood. Farmer 7 from Kaffrine, 50 years old, eight years’ experience of practicing FMNR argues: ‘the benefits of FMNR are not limited only to wood but also FMNR help fertilize the soil, increase yields, and fight against erosion’.

For the farmers, the tree uses procedures discourage them from practicing FMNR because of long and often complicated permit processes. From the data corpus, farmers reported a 12 km average, with a minimum of 1 km and a maximum of 40 km of distance to get a permit from the nearest forest service. As for the duration, a 5-day average is reported by farmers, ranging from 1 to 30 days waiting period.

Nonetheless, foresters explained that for FMNR trees, no paid permit is required. However, pursuing the free permit yields costs for the farmer, for example the trip to the forester’s office and in some cases the forester’ fuel that farmers should pay for the prescribed technical assessment. In addition, tree pruning is free of charge officially. But, from the field, informants made several references to pruning fees that the farmers are asked to disburse. These illustrate farmers suggestion to reduce the tree use procedures and the costs related to the use of FMNR trees (see the next section).

3.3 Actors’ differentiated suggestions to improve tree use procedures

For the foresters, to ensure that the tree use procedures incentivise farmers to grow trees on their farms, 54% of their suggestions (n = 40) relate to the creation of a motivation system for the farmers, such as rewarding the best FMNR practicing farmers with agricultural inputs and equipment. Sensitization of farmers on tree growing techniques and the Forestry Code covered 46% of the suggestions, followed by the need to simplify and shorten the procedures (29%) through, for example, the exemption of fees regarding FMNR trees’ cutting. Harmonizing the understanding of the Forestry Code among municipal councillor constituted 13% of the suggestions.

As part of the eventual solutions for addressing FMNR policy gaps, the foresters have shared their opinions regarding the opportunity for a FMNR policy reform through a decree for example. The majority (67%) think that a reform of FMNR policy is not needed because in their opinion, the current Forestry Code is sufficient, and the current tree use procedures are not constraining for farmers. For them, the Forestry Code is clear on tree use procedures and gives farmers the right to use their FMNR trees with a free permit delivered by the WFS. For these foresters, the priority is to inform and sensitize the farmers on the Forestry Code ‘so that they are encouraged to grow more trees on their farms and access them without paying for the permit and taxes’ (ST6 from Fatick, five years of professional experience). In addition, making the tree procedures easy would lead to accelerated deforestation as ST5 from Fatick, with more than 20 years’ professional experience puts it ‘if we make the use of trees easy, over the years, there will be nothing left to exploit because the demand will be higher than the production’. In the long term, “such a reform for me will help farmers’ totally destroy the tree resources rather than regreening it’ (ST16 from Kaolack, 20 years professional experience).

On the contrary, for 21% of foresters, a reform through a decree is necessary to incentivise farmers to nurture trees by lifting certain constraints regarding the use of the trees on farm by the farmers. ST1 a forester from Kaolack with less than five years’ professional experience explained that a decree could motivate the farmers by lifting the requirement for the forester’s prior investigation of the trees on farm, and reduce the taxes and permit fees. 12% were not sure.

Regarding the field animators, 66% of the suggestions concern the sensitization and training of farmers on tree growing practices and on national regulations. Another 44% of the suggestions point to the need to motivate FMNR practicing farmers through awards and donation of seedlings, agricultural inputs, and equipment. As for 33% it is necessary to lift all fees related to pruning, and the felling of FMNR trees. Likewise, for 31% simplifying the procedures is critical as well as reducing the distances by increasing the number and distribution of forestry units (11%). Other suggestions include the reduction of fines and their rates, replacing permit fees with planting the equivalent number of trees that are cut.

Lastly, regarding farmers’ suggestions for solutions, 71% of the suggestions concern the shortening of the procedures and making the permit available at the local level. For that purpose, farmers suggest vesting the local authorities such as the village chief, the mayor and/or the local WFS officer with the power to issue the permit at local level. Lifting all taxes and costs regarding the use of FMNR trees follows with 44% of the suggestions. The logic being that the FMNR trees are different from the trees inside the forest because of the farmers’ care, therefore, they should be treated differently as explained by farmer22, male from Kaffrine, 65 years old, 12 years of FMNR practice. The reduction of permit fees extends to 22% of the suggestions while 17% point to sensitization and capacity building of farmers and the securing of FMNR field through vigilante committees. Other few suggestions concern motivating FMNR farmers through rewards, reduction of the severity of the fines and replacing the permit fees with planting of equivalent number of trees as cut by the farmers.

4. Discussion: institutional stickiness and change pathways in Senegal and the Sahel

In West African Sahelian countries, countless evidence exists on the merit of FMNR and other agroforestry practices to support sustainable development of both social and ecological systems. In Senegal specifically, development policy frameworks also acknowledge FMNR, and agroforestry practices help achieve the country’s development strategy, especially for agro-sylvo-pastoral development, land degradation neutrality, and climate commitments. The longstanding obstacles to FMNR and agroforestry development are also known, as legal, technical, cultural, and financial (Niang Citation1992; Winterbottom and; McGahuey Citation2021). While the technical and technological aspects have seen investment and improvement by practitioners, donors and the research community through projects implementation, the legal and political obstacles seem to be met with little change (Ribot Citation1999b; Bernard et al. Citation2019). Despite continual reform of the Forestry Code, farmers are yet to gain full ownership and use rights over the trees they nurture on their property without permits granted by the Water and Forestry Services (Elbow and Rochegude Citation1991). Why aren’t there any specific national policy frameworks for governing FMNR, and agroforestry in the country? Why is FMNR and agroforestry policy change so challenging? In the following, we apply to our case study the 4Is lens (Institutions, Information, Ideas, Interests) developed by Brockhaus and Angelsen (Citation2012) to discuss our study results, and explore how, and why institutions governing FMNR and agroforestry resources in Senegal resist reform.

The Institutions defined as the ‘rules of the game’, the norms and regulations, that are (in)formal arrangements, shaped by history, and enabling certain behaviour, thus resulting in institutional path dependencies and stickiness. Current forestry codes in the Sahel region take root in colonial legacies where colonized communities were restricted access to high value natural resources, through the institution of lengthy administrative and costly permit processes that ignore communities’ entitlements and customary rights to those resources (Ribot Citation2001; Montagne and Amadou Citation2012; Yatich et al. Citation2014). For example, reviewing the history of Sahelian forestry policy, Ribot (Citation2001) showed how, from the 1900s the French colonial power issued the first West African forestry legislation that introduced i) the permit requirement, ii) created protected/classified areas and species, iii) limited (non)commercial use rights (i.e., usufruct rights) for the local communities, iv) instituted the state ownership and control of land and forest resources, and v) penalties for infractions. Furthermore, the post-colonial Sahelian states’ regulations introduced to govern agricultural and forestry production systems were constraining, punitive, disempowering, and sources of disincentives to rural communities (Yatich et al. Citation2016). For the authors, the severe forestry institutions aiming to protect trees (especially the indigenous trees species that are vital for rural livelihoods), have failed to balance ecological, socio-economic, and cultural objectives, hence compromising the sustainable use and regeneration of these trees. In our case, the dominant suggestion from the forestry officers centred around the creation of incentive systems to motivate the farmers. Such recommendations subtly suggest conscious acknowledgement of the constraining nature of current regulations. However, formal and informal local structures including local conventions and by-laws still play a critical role in farmers’ incentives for wider adoption and management of FMNR and other agroforestry practices (Ajayi et al. Citation2016; Binam et al. Citation2017).

In addition, the generalised institutional arrangements for permits to transport and sell agroforestry product in addition to the constraining use right, could prevent the local communities, specifically the poorest among them, from reaching important market share. Such conditions cluster them into a subsistence logic, whereas other parties, the elites with more financial assets can capture higher commercial profits (Ribot Citation2001). These provisions endorse a neoliberal conception of forestry resources management and use, while ignoring the specificities of the agroforestry parklands centred on integrated livelihoods systems, and not merely monoculture tree production.

The Information relates to data, knowledge, and evidence construction as well as the politics of numbers to make the institutions legal, legitimate, and acceptable to the society. In this sense, public policies can use scientific knowledge, or technical expertise to grant or deny certain actors and organisations power and authority over forestry resources. While ‘scientific’ knowledge is legitimised and valued, local or indigenous knowledge may be undermined. For instance, the contemporary Sahelian forestry codes including in Senegal build on their colonial roots, and techno-bureaucratic logic to vest the management of trees (both planted, or naturally regenerated, located inside forests and in the agro-sylvo pastoral systems) to the Water and Forestry Services (Elbow and Rochegude Citation1991; Yatich et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, in Francophone West Africa, the Water and Forestry Services were able to establish their authority and exert control over access, transportation, and marketing of forestry resources due to their alleged i) scientific forestry knowledge gained from their vocational training, and ii) technical control over forestry code and forest management plans recognised by the state regulations (Ribot Citation2001; Yatich et al. Citation2016). Conversely, local communities who may not have such scientific knowledge are seen as ‘unfit’ to manage forest resources. Despite, the resurging of ‘participation’ and community forestry, local knowledge, customary regulations, and socially embedded governance practices are yet to be acknowledged in public policies and decision-making (Elbow and Rochegude Citation1991; Yatich et al. Citation2014, Citation2016).

From the above, information is not neutral, but political and politicized. For example, despite scientific evidence on the positive impact of pruning and other sylvicultural practices on local species’ production (Bayala et al. Citation2008, Citation2022), forestry regulations in the region continue to restrain and prosecute the pruning of the local tree species, especially those considered protected. In addition, our results have shown diverse perceptions and suggested solutions from the stakeholder groups, thus pointing to a need to diversify the sources of knowledge and data to inform policy formulation and refine implementation. Further example is the forestry code provisions (e.g., Art.19) that require farmers to prove their land ownership and establish management plans for their farms while the national domain law (1964) stated that land belong to the State.

The Ideas conceived as normative policy discourses are constructed and disseminated by different actors and groups through the institutions, and information channels. Current data and statistics use, convey, and sustain a Malthusian idea of resources depletion because of population growth and anthropic pressure, where local communities are presented as a threat to resource preservation. Such ideas are used to justify and maintain severe forestry codes and regulations that do not acknowledge or sufficiently value local people’s environmental consciousness and agency. A mainstream narrative being that if the legislations are made easier, the un-regulated farmers will destroy the forest, hence ignoring the customary regulations that had kept the forest resources standing before the colonial and post-colonial state (Peluso Citation1993; Fairhead and Leach Citation1996). The foresters’ suggestion of training farmers’ and building their capacity is not surprising, as they feed off this idea of farmers’ lacking capacity to make technical decisions over forest uses and management (Ribot Citation1999a; Dakpogan et al. Citation2022). Such distrust in local communities’ agency, seen as a threat to forestry resources is a continuation of the French colonial system that created and maintained a fear for deforestation and a looming crisis of forest resources at the hand of local communities (Ribot Citation1999b).

The ideas are meant to express and safeguard specific Interests defined as the actors’ advantages that are horizontally and vertically negotiated, and can be material (e.g., political, technical, and financial) and/or immaterial (e.g., symbolic) for different actors and groups. What, and whose interests are being kept through such constraining regulations, which for the most part are concerned with how forestry resources are used and less with who profits, and carries the burdens? Currently, the regulations lean toward an alleged environmental protection rather than listening, understanding, and addressing the farmers’ interests. This reinforces a narrative of a dichotomy between farmers’ interests and environmental protection. Even regarding the environmental protection focus, the constraining and unclear regulations give room to various interpretations and enforcement of the law as our results have shown, and thus opportunities for bribes in permit delivery processes. Rarely are there questions about what landscape restoration opportunities are missed because of such constraining rules and regulations. Our results suggest a counter narrative, one of a more prosperous landscape when farmers know that the regulations are supportive and allow their ownership of the fruits of their labour. From our results, farmers’ main suggestions point to the simplification of the tree use procedures, to incentivise them to undertake FMNR at scale. Positive results have been obtained elsewhere, such as in Niger where FMNR practices helped restore over 5 million hectares of degraded land in the Zinder and Maradi regions (Baggnian et al. Citation2013; Garrity and Bayala Citation2019). A presidential decree was issued in Niger to further support the practice through enhanced local tree use rights, a process that should inspire change in neighbouring countries, such as in Senegal.

5. Conclusion and policy recommendations

Despite the abundant literature on FMNR, gaps remain on the policy and regulatory aspects, and their implications for enabling the uptake of land restoration. Contributing to filling these knowledge gaps, the case study in Senegal showed that FMNR and agroforestry in general appear in the country’s development frameworks. However, the sector lacks its own policy and regulatory framework, inhibiting its ability to thrive. As a result, forestry-related laws are enforced for the management of agroforestry systems although they were not meant for the management of trees on farm. The enforcement of these laws, for example the Forestry Code vary according to the understanding and interpretation of the water and forestry officers as they exercise their duty. The diversity of interpretations was illustrated in this study by the variation in foresters’ responses regarding the procedures for using trees on farm.

Regarding the stakeholders’ perceptions, there were variations among and across the three categories of actors. Most field animators and farmers’ participants found the procedures for tree use burdensome and not entirely conducive for wider adoption of FMNR. However, the foresters for the most part find the procedures not burdensome and vital to prevent deforestation by farmers.

In terms of suggested solutions, the field animators and foresters propose sensitization, technical capacity building of farmers and award systems to motivate the farmers to practice FMNR. However, the farmers suggest the simplification of the tree use procedures through the shortening of the permit procedures and the reduction of the related cost.

As recommendations from the case study, it is critical to formulate a specific agroforestry policy, based on legal provisions that are appropriate to the management of trees on farm. In addition, the government could issue a new decree regulating the practice of FMNR and the management of trees in agroforestry systems in application of the Article 19 of the current Forestry Code, that article being the only one that mentions the term ‘farm’ (champs). This new decree could:

Recognise farms as specific entities dedicated to agricultural production with integrated trees (agroforestry) distinct from the forest dedicated to forestry production or protection.

Recognise and define a specific status for trees on farm that is distinct from that of trees in the forest.

Attribute the management of trees on farm to their own regulations and a specific agroforestry development policy, distinct from the trees inside the forest, which are subject to the management regimes of the Forestry Code (FC).

Specify the conditions of application of the free permit and tax exemption for the use of trees on farm established in Article 19 of the FC; and in adequacy with the status of protected tree species in the country (ref. Article 51 of the FC application decree).

Clarify the exemption of farms of less than 5 ha from the simple management plan requirement in accordance with Article 1 of the decree implementing the FC, which does not impose this condition on forest areas of less than 5 ha.

A sub-national and local-level decree promoting the practice could further support the national-level reform.

Meanwhile, it is important to produce a manual or dashboard of all the regulations related to the practice of FMNR and agroforestry to guide the daily work of the Water and Forestry Services who enforce and oversee public policy on natural resources management. This manual could also be translated into local languages for more effective information transfer, training and awareness of farmers and other local stakeholders to help boost widespread adoption and scaling up of landscape restoration. These suggestions of reform (both FMNR decree and agroforestry policy) and information sharing will support the achievement of the country’s national and international commitments such as the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and the implementation of nature-based solutions to combat the adverse effects of climate change and reverse land degradation.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Regreening Africa project funded by the European Union and implemented by World Agroforestry and partners and the Transformative Partnership Platform on Agroecology. Special thanks to World Vision Senegal for their support in data collection. We express our utmost gratitude to the respondents for their participation in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajayi OC, Akinnifesi FK, Ajayi AO. 2016. How by-laws and collective action influence farmers’ adoption of agroforestry and natural resource management technologies: lessons from Zambia. For Trees Livelihoods. 25(2):102–113. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2016.1153435

- Alinon K, Kalinganire A. 2016. Bylaws as complementary means of tenure security and management of resources conflicts: synthesis of various West African experiences. For Trees Livelihoods. 25(2):114–119. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2016.1158667

- Ba M, Bourgoin J, Thiaw I, Soti V. 2018. Impact des modes de gestion des parcs arborés sur la dynamique des paysages agricoles un cas d’étude au Sénégal. Vertigo. 18(2):1–26. doi: 10.4000/vertigo.20397

- Baggnian I, Adamou MM, Adam T, Mahamane A. 2013. Impact des modes de gestion de la Régénération Naturelle Assistée des ligneux (RNA) sur la résilience des écosystèmes dans le Centre-Sud du Niger. J App Bioscience. 71(1):5742–5752. doi: 10.4314/jab.v71i1.98819

- Bandiaky-Badji S. 2011. Gender equity in Senegal’s forest governance history: why policy and representation matter. Int For Rev. 13(2):177–194. doi: 10.1505/146554811797406624

- Bayala J, Ky-Dembele C, Coe R, Binam JN, Kalinganire A, Olivier A. 2022. Frequency and period of pruning affect fodder production of Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp. and Pterocarpus erinaceus Poir. The Sahel. doi:10.1007/s10457-022-00779-y. Agrofor Syst.1-15.

- Bayala J, Ouedraogo SJ, Teklehaimanot Z. 2008. Rejuvenating indigenous trees in agroforestry parkland systems for better fruit production using crown pruning. Agrofor Syst. 72(3):187–194. doi: 10.1007/s10457-007-9099-9

- Bayala J, Sanou J, Bazié HR, Coe R, Kalinganire A, Sinclair FL. 2020. Regenerated trees in farmers’ fields increase soil carbon across the Sahel. Agrofor Syst. 94(2):401–415. doi: 10.1007/s10457-019-00403-6

- Bayala J, Sanou J, Teklehaimanot Z, Kalinganire A, Ouédraogo SJ. 2014. Parklands for buffering climate risk and sustaining agricultural production in the Sahel of West Africa. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 6:28–34. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2013.10.004.

- Bernard F, Bourne M, Garrity D, Neely C, Chomba S. 2019. Policy gaps and opportunities for scaling agroforestry in sub-Saharan Africa: recommendations from a policy review and recent practice. Nairobi: World Agroforestry (ICRAF).

- Binam JN, Place F, Djalal AA, Kalinganire A. 2017. Effects of local institutions on the adoption of agroforestry innovations: evidence of farmer managed natural regeneration and its implications for rural livelihoods in the Sahel. Agric Food Econ. 5(1):1–28. doi: 10.1186/s40100-017-0072-2

- Brockhaus M, Angelsen A. 2012. Seeing REDD+ through 4Is: a political economy framework. Analyzing REDD+: challenges and choices. Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research. Bogor. p. 15–30.

- Chomba S, Sinclair F, Savadogo P, Bourne M, Lohbeck M. 2020. Opportunities and constraints for using farmer managed natural regeneration for land restoration in sub-Saharan Africa. Front. for. glob. Change. (3): 571-679.

- Dakpogan A, Bayala J, Ouattara I, Ellington E. 2022. Boosting FMNR in the Sahel for the UN decade of restoration. Policy brief. Great Green Wall.

- de Foresta H. 2013. Advancing agroforestry on the policy agenda – a guide for decision-makers. For Trees Livelihoods. 22(3):213–215. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2013.806162

- Dewees PA. 1995. Trees and farm boundaries: farm forestry, land tenure and Reform in Kenya. Africa: J Of The Int Afr Inst. 65(2):217–235. doi: 10.2307/1161191

- Diallo B, Akponikpè M, Fatondji PI, Abasse D, Agbossou EK. 2019. Long-term differential effects of tree species on soil nutrients and fertility improvement in agroforestry parklands of the Sahelian Niger. For Trees Livelihoods. 28(4):240–252. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2019.1643792

- Elbow KM, Rochegude A. 1991. Guide pratique des codes forestiers du Mali, du Niger, et du Sénégal. University of Wisconsin-Madison: US. Land Tenure Center.

- Fairhead J, Leach M. 1996. Misreading the African landscape: society and ecology in a forest-savanna mosaic. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139164023

- Faye P, Haller T, Ribot J. 2018. Shaping rules and practice for more justice. Local conventions and local resistance in Eastern Senegal. Hum Ecol. 46(1):15–25. doi: 10.1007/s10745-017-9918-1

- Fleming A, O’Grady AP, Mendham D, England J, Mitchell P, Moroni M, Lyons A. 2019. Understanding the values behind farmer perceptions of trees on farms to increase adoption of agroforestry in Australia. Agron Sustain Dev. 39(9):11. doi: 10.1007/s13593-019-0555-5

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations-FAO. 2013. Advancing agroforestry on the policy agenda: a guide for decision-makers, by G. Buttoud G, Ajayi O, Detlefsen G, Place F, Torquebiau E. Agroforestry. Working Paper 1. Rome. FAO. 1–37.

- Garrity D. 2012. Agroforestry and the future of global land use. Netherlands:Springer. p. 21–27. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4676-3_6

- Garrity DP, Bayala J. 2019. Zinder: farmer-managed natural regeneration of Sahelian parklands in Niger. In: van Noordwijk M, editor. Sustainable development through trees on farms: agroforestry in its fifth decade. Nairobi: World Agroforestry (ICRAF). p. 151–172.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. 2006. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method. 18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Hagaman AK, Wutich A. 2017. How many interviews are enough to identify meta themes in multi sited and cross-cultural research? Another perspective on Guest, Bunce, and Johnson’s (2006) landmark study. Field Method. 29(1):23–41. doi: 10.1177/1525822X16640447

- Leakey RR. 1999. Agroforestry for biodiversity in farming systems. Florida: CRC Publishers. doi: 10.1201/9781420049244.ch8.

- Lohbeck M, Albers P, Boels LE, Bongers F, Morel S, Sinclair F, Takoutsing B, Vågen TG, Winowiecki LA, Smith-Dumont E. 2020. Drivers of farmer-managed natural regeneration in the Sahel: lessons for restoration. Sci Rep. 10(1):1–11.

- Mansourian S, Berrahmouni N. 2021. Review of forest and landscape restoration in Africa 2021. Rome: FAO.

- Mbow C, Van Noordwijk M, Luedeling E, Neufeldt H, Minang PA, Kowero G. 2014. Agroforestry solutions to address food security and climate change challenges in Africa. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 6:61–67. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2013.10.014.

- McGahuey M. 2021. Agroforesterie : augmenter durablement la productivité des sols dans le Sahel ouest-africain. ETFRN News. 60:221–394.

- Montagne P, Amadou O. 2012. Rural districts and community forest management and the fight against poverty in Niger. The household energy strategy–a forestry policy to supply urban areas with household energy. Field Actions Sci Rep. 6:1–14.

- Muthee K, Duguma L, Majale C, Mucheru-Muna M, Wainaina P, Minang P. 2022. A quantitative appraisal of selected agroforestry studies in the Sub-Saharan Africa. Heliyon. 8(9):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10670

- Ndlovu NP, Borrass L. 2021. Promises and potentials do not grow trees and crops. A review of institutional and policy research in agroforestry for the Southern African region. Land Use Policy. 103:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105298.

- Niang A. 1992. Les blocages de l’agroforesterie au Sénégal. Working paper 26. Canada. Laval Centre Sahel.

- Peluso NL. 1993. Rich forests, poor people: resource control and resistance in Java. Berkeley, US: University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/california/9780520073777.001.0001.

- Peluso NL. 1993. Rich Forests, Poor People: Resource Control and Resistance in Java. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Reij C, Garrity D. 2016. Scaling up farmer‐managed natural regeneration in Africa to restore degraded landscapes. Biotropica. 48(6):834–843.

- Ribot J. 2001. Science, use rights and exclusion: a history of forestry in francophone West Africa. Senegal: IIED. pp. 1–19.

- Ribot JC. 1999a. Decentralization, participation and accountability in Sahelian Forestry: legal instruments of political-administrative control. Africa. 69(1):23–65. doi: 10.2307/1161076

- Ribot JC. 1999b. A history of fear: imagining deforestation in the West African Dryland Forests. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 8(3–4):291–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.1999.00146.x

- Suharti S, Nuroniah HS, Rahayu S, Dewi S, Rahayu S, Dewi S. 2022. What makes agroforestry a potential restoration measure in a degraded conservation forest? Forests. 13(2):267. doi: 10.3390/f13020267

- Tsonkova P, Mirck J, Böhm C, Bettina F. 2018. Addressing farmer-perceptions and legal constraints to promote agroforestry in Germany. Agroforest Syst. 92(4):1091–1103. doi: 10.1007/s10457-018-0228-4

- Yatich T, Kalinganire A, Place F, Jeremias M. 2016. Moving beyond forestry laws through collective learning and action in Sahelian countries. For Trees Livelihoods. 25(2):99–101. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2016.1153434

- Yatich T, Kalinganire A, Weber JC, Alinon K, Dakouo J, Samaké O, Sangaré S 2014. How do forestry codes affect access, use and management of protected indigenous tree species: evidence from West African Sahel. Occasional Paper 15. Nairobi. World Agroforestry.

- Zomer RJ, Trabucco A, Coe R, Place F, van-Noordwijk M, Xu JC 2014. Trees on farms: an update and reanalysis of agroforestry’s global extent and socio-ecological characteristics. Working Paper 179.1-33. Nairobi. World Agroforestry.

Appendix

Original French version of the articles of the forestry law cited in the paper

« Les droits d’exploitation des forêts et terres à vocation forestière du domaine national appartiennent à l’Etat. » art. 9 code forestier 2018 (CF).

« La gestion des ressources du domaine forestier protégé est transférée aux collectivités territoriales. » art.9 CF

« Le droit d’usage des populations riveraines des forêts peut s’exercer, sur des parcelles mises en exploitation, sans que les exploitants puissent prétendre à compensation. Toutefois, la nature et la quantité des produits sont au préalable précisé dans le cahier des charges de l’exploitation ». Article 33 du CF

« Dans les forêts du domaine national, les populations riveraines disposent des droits d’usage suivants: le ramassage du bois mort et de la paille; la récolte des fruits, feuilles, racines, écorces, gommes, résines et miel à des fins alimentaires ou médicinales; le parcours du bétail et l’émondage des espèces fourragères; la coupe de bois de service destiné à la construction et à la réparation des habitations situées dans le terroir; l’utilisation du bois sacré à des fins de culte. Ces droits d’usage n’entraînent aucun droit de disposer des lieux ». l’Article 29 du CF

« Les produits acquis en vertu du droit d’usage, strictement limités aux besoins personnels et familiaux des usagers, ne peuvent circuler hors du terroir d’habitation du bénéficiaire qu’après autorisation du Service des Eaux et Forêts, Chasses et de la Conservation des Sols » Article 32 CF

« L’exploitation de toute ressource forestière du domaine forestier est assujettie au paiement préalable de taxes et redevances dans des conditions et formes définies par décret à l’exception des forêts privées et du droit d’usage ». Article 12 du CF

« L’abattage, l’arrachage, la mutilation et l’ébranchage des espèces intégralement protégées sont formellement interdits, sauf dérogation accordée par le Service des Eaux et Forêts, Chasses et de la Conservation des Sols, pour des raisons scientifiques ou médicinales. Les espèces partiellement protégées ne peuvent être abattues, ébranchées ou arrachées sauf autorisation préalable du Service des Eaux et Forêts, Chasses et de la Conservation des Sols. Les propriétaires de formations forestières artificielles à base d’essences figurant sur la liste des espèces protégées partiellement ou intégralement peuvent les exploiter à condition de se conformer aux dispositions du présent décret ». Article 50 du Décret no 2019-110 du 16 janvier 2019 d’application du code forestier de 2018.

« L’exploitation et ou la valorisation des produits et services forestiers dans les forêts relevant de la compétence des collectivités territoriales est assujettie à l’autorisation préalable du Conseil départemental concerné après avis du Conseil municipal concerné. Le permis d’exploitation est délivré par le Service des Eaux et Forêts, Chasses et de la conservation des sols au vu de l’autorisation établie ». Article 13 du CF

« La coupe, l’abattage, l’ébranchage et l’écorçage d’arbres à l’intérieur du périmètre communal hors d’un domaine privé, sont soumis à l’avis du Conseil municipal de la commune concernée. Toutefois, l’autorisation de coupe des formations ligneuses ayant un rôle de protection d’équipements collectifs ou de l’environnement, ainsi que celle pour les arbres remarquables, les arbres semenciers sélectionnés ou essences protégées, sont soumises à l’avis technique du Service des Eaux et Forêts, Chasses et de la Conservation des Sols ». Article 20 of the CF

« La collecte et la coupe de produits forestiers, lorsqu’elles sont réalisées par la personne physique ou morale propriétaire de la plantation, sont libres de redevances. Toutefois, l’exploitation de ces produits se fait conformément aux prescriptions du plan d’aménagement ou du plan simple de gestion de la forêt. Ces mêmes dispositions sont applicables aux propriétaires d’un champ ou d’une exploitation sylvicole qui souhaitent exercer des activités de valorisation des services forestiers ou de coupe, d’ébranchage, d’abattage et d’écorçage sur les arbres plantés et/ou issus de régénération naturelle assistée ou non, se trouvant à l’intérieur de leur domaine ». Article 19 du CF

« Les produits acquis en vertu du droit d’usage, strictement limités aux besoins personnels et familiaux des usagers, ne peuvent circuler hors du terroir d’habitation du bénéficiaire qu’après autorisation du Service des Eaux et Forêts, Chasses et de la Conservation des Sols » Article 32 CF

« Les produits provenant des exploitations régulières ne peuvent être transportés en dehors du périmètre de leur coupe et stockés ailleurs qu’après délivrance par le Service des Eaux et Forêts, Chasses et de la Conservation des Sols d’un permis de circulation et d’un permis de dépôt certifiant la provenance des produits, leur nature, leur quantité et la régularité de l’exploitation. La délivrance ne peut être refusée que si l’exploitation n’est pas conforme aux dispositions de l’article 19 du présent Code ou si l’exploitant ne s’est pas acquitté du paiement de la redevance ou des droits issus de la vente de coupe par adjudication. » Art.21 CF.

« […] En dehors des dérogations prévues par la loi, l’exploitation des produits non contingentés requiert l’obtention du permis de coupe tandis que celle des produits contingentés nécessite au préalable l’obtention de la carte professionnelle d’exploitant forestier pour les organismes ou la carte de producteur local pour les membres des GIE de blocs des forêts aménagées ». Article 5 du CF.

« Aucun produit forestier n’est admis à -circuler s’il n’est accompagné d’un permis de circulation délivré par le Service des Eaux et Forêts Chasses et de la Conservation des Sols, sur présentation de la quittance de vente de saisie, de l’autorisation d’exploiter, du permis d’exploitation ou de dépôt. […] Sa délivrance est gratuite », Art. 14, Decret d’application du CF.