?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study of adventure sports learners expands on earlier work on adventure sports coaching. We examine learners’ perceptions of their coaching and its effect on their self-efficacy and independence as adventure sports performers. We utilise a convergent mixed approach that deploys the Outdoor Recreation Self-Efficacy Scale, pre- and post-coaching, and a reflexive thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews. The findings indicate improved self-efficacy and greater independence as a result of the coach’s practice, supporting our initial conjecture that the adventure sports coaches in this study developed independence as a definable outcome of their coaching practice.

In the latest set of data from the Active Lives Survey (Sport England, Citation2022) over ten million adults in the UK had participated in an adventure sport in the 12 months prior to the survey. Notably, 3.5 million of those adults had participated in the last 28 days, a number that has steadily increased in the last five years of survey data. Adventure sports are a growing subset of physical activity. In part, explaining a recent increase in academic attention (Durán-Sánchez et al., Citation2020), which is of interest to practitioners, coach educators and policymakers. However, as reported by Durán-Sánchez et al. the majority of research to date focuses on high-level coaches. As such, they call for more perspectives to be taken in further understanding adventure sports. This article follows on from previous investigations into adventure sports coaching practice (Christian et al., Citation2020; Collins & Collins, Citation2021; Eastabrook et al., Citation2022; Mees et al., Citation2020) in order to examine learners’ perspectives on the impact of coaching they have received, thus diversifying the insight into adventure sports coaching practice and triangulating previous findings with alternative data sources (Olsen, Citation2014). This article offers a brief context and overview of background literature before reporting on the methods used, results found, and ensuing discussion and implications centred around learners’ perspectives about coaching they had received.

What do learners seek from their adventure sports coaching?

Both Collins et al. (Citation2015) and Christian et al. (Citation2017) report that high-level adventure sports coaches teach in adventurous environments and aim to develop performers who are flexible, adaptable, and independent of the coach. Eastabrook and Collins (Citation2020) offer insight using learners in a single location in the UK. Those learners sought three types of experience: a holistic one sharing commonality with the experience economy and including social and cultural induction in the sport or discipline, an authentic experience where the learning takes place in an adventurous environment that the learner feels is real to them and, finally, a developmental experience where they expand their skills and independence.

Independence and participation in adventure sports should be considered in relation to three factors, these being the connection with natural places, opportunity for social engagement and degrees of challenge (Collins & Brymer, Citation2020; Ewert et al., Citation2013; Sugerman, Citation2001; Varley & Semple, Citation2015). From Eastabrook and Collins (Citation2020) limited sample, these three aspects of adventure are vital to well-received coaching. More specifically, much has been discussed in coaching and adventure sports coaching practice, regarding a Professional Judgement and Decision-Making (PJDM), or ‘it depends’ approach to coaching (Collins et al., Citation2012; Mees et al., Citation2020; Collins et al., Citation2022). While coaches are encouraged to choose the most appropriate strategy at the most appropriate time for the desired outcome, little detail has yet to be offered regarding what strategies adventure sports coaches are deciding between. It would appear that the learners’ personalised conception of adventure and independence are the fundamental considerations of the adventure sports coaches’ PJDM (Eastabrook & Collins, Citation2021).

Further insight is offered by Eastabrook et al. (Citation2022) investigated coaching practice in relation to the development of independence. They identify independence as an aspect desired by both the coaches and learners. A philosophical position held by the coaches as supported by their epistemological stance and chain (Collins et al., Citation2015). As a principal reason for learners to seek coaching (Eastabrook & Collins, Citation2020). Eastabrook and Collins (Citation2020) reported that coaches prepare and equip learners to develop skills independently of the coach during programmes, with coaches expecting learners to realise their independence post-coaching. Coaching for independence in an adventure sports context includes two unique aspects. The first is the nature of performance in the adventure context. Specifically, coaches aimed to develop adaptable and flexible technical and tactical performances that reflected the hyper-dynamic performance environments typical in adventure sports. This first aspect differentiates the nature of performance as independent from the coach, as in the coach need not, indeed should not, be present. Coaching for independent performance is the aim of many coaches, however, the risks and remoteness associated with adventure sports makes independence in this context a significant undertaking. Secondly, and in parallel to the first, that coaches equipped learners with sufficient knowledge to continue their independent development after the coaching session, the skills of learning (see Learnacy- reflection, resilience, resourcefulness, reciprocity, (Claxton, Citation2003)), situational awareness and comprehension of the performance (Eastabrook et al., Citation2022), in essence, the non-technical skills, decision making and consideration of the practicalities a for safe, independent practice. We speculate that this differentiates the adventure sports coach from other outdoor professionals, the aforementioned guide, and also in outdoor education (Collins et al., Citation2012).

Consequently, in answering the call of Durán-Sánchez et al. (Citation2020), we investigate the impact of coaching for independence using learners and their personal experiences as the missing part in our comprehension of adventure sports coaching at present. This position increases the diversification of researched positions, aiming to expand the findings of Eastabrook et al. (Citation2022) by seeking the learners’ perspectives. Consequently, this article utilises a mixed-method approach to increase the diversification further.

Methodology

Driven by our pragmatic research philosophy (Morgan, Citation2014), we adopted a converging mixed-methods approach (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011; Fetters et al., Citation2013), a quantitative part using the ORSES (Mittelstaedt & Jones, Citation2009) and a qualitative part that consisted of a reflexive thematically analysis of semi-structured interviews. The authors take a postpositive stance, drawing on pragmatism as an underpinning philosophical position (Morgan, Citation2014). We subscribe to Olive’s (Citation2020) view that research is through the author, that multiple realities exist where we are aiming to find the most probable narrative for a given circumstance. Consequently, meaning is constructed from the interplay between subject and object where the authors’ backgrounds and experiences are ideally placed to make sense of this interplay, a social constructivism (Palincsar, Citation1998). This position was critical in developing open and honest responses from the participants and in the reflexive thematic analysis.

Participants

ORSES

We approached 28 participants who had booked onto coaching sessions with five different adventure sports coaches across a range of water and mountain-based adventure sports. Twenty-one adventure sports participants consented to take part in part of the study (male = 10, female = 11), age (min = 20, max = 65, M = 40.0, SD = 13.6). These participants varied in experience (min = 3 yrs, max = 40 yrs, M = 15.2 yrs, SD = 12.7 yrs). The selection criteria were to seek coaching in an adventure sports, that being provided by a suitable qualified coach and being willing to complete the ORSES three times.

Interviews

From the original group of participants, a heterogeneous sample (n = 10, male, n = 2; female, n = 8); age (min = 21, max = 61, M = 39.1, SD = 14); years experience of participation (min = 2, max = 30, M = 11.5, SD = 10) and discipline (water-based, n = 6; mountain-based, n = 4), were recruited, 1 from 10 different coaching sessions (detailed in ). In addition to the criteria required for the ORSES, these participants needed to be willing to undertake an interview.

Table 1. Details of the participants interviewed.

Authors

Both authors are experienced and highly qualified adventure sports coaches with over 50 years of combined experience in a range of adventure sports. They hold senior-level certifications in paddlesports, mountaineering and skiing in addition to their academic experience and qualifications.

Procedure

Following ethical approval from the University of Central Lancashire and informed consent from the participants, we applied a convergent mixed approach. We sought two perspectives regarding the participant’s independence and how participants perceived the development of their own independence. We collected both quantitative and qualitative data conducted analysis in a similar time frame to confirm or disconfirm each other (Fetters et al., Citation2013). The quantitative part, ORSES, was applied three times: immediately prior-, immediately post and a third three months after the coaching with a sample of 21. The extant literature guided the semi-structured interviews, the qualitative part. The semi-structured interviews allowed for a ‘deeper dive’ into the coached experience of a sub-group (n = 10) of the original group (n = 21). The interviews took place between seven and 14 days after the coached programme. The research design is illustrated in

Mittelstaedt and Jones (Citation2009) devised the ORSES to gain an individual’s perception of their level of enjoyment and skills when participating in outdoor recreation activities. The ORSES offers an outdoor-focused tool that provides insight into the degree of self-efficacy that individuals have over their participation. Additionally, Bandura (Citation1977) maintains that self-efficacy is context-specific, questioning the value of generalisable measurements. In this respect, the ORSES is a highly appropriate tool over more generic instruments. The ORSES is also preferred because of its simplicity and ease of use. The ORSES has a strong internal consistency, building on the work of Bandura, and has 17 items split into two sections: enjoyment/accomplishment and skills/competence.

A cognitive pilot (Willis, Citation2005) was undertaken with a representative sample (n = 4) to confirm the appropriateness of the ORSES. Feedback was positive, and no changes were required, the simplicity was valued by these participants (). The ORSES was administrated via a paper form manually imported into Excel, with statistical analysis conducted with the latest version of IBM SPSS.

Table 2. Outdoor Recreation self-efficacy Scale.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a subgroup of the original population to provide increased depth and insight. An initial interview guide was created informed by the existing literature. Cognitive pilot interviews (Willis, Citation2005) were conducted with a representative sample of two adventure sports learners from the first author’s professional network. Changes made to the guide sheet included (1) the rewording of questions for clarity, (2) the addition of prompts, and (3) grammatical changes. A final interview schedule was then standardised for the participants (). A mutually agreed date and time for a video interview was agreed with the participants (Deakin & Wakefield, Citation2014), interviews were conducted via Teams. This process allowed interviews to be conducted between 7 and 14 days post programme, ensuring a balanced opportunity for reflection and freshness of experience (Mean duration = 35 mins). Participants were asked an opening question and then encouraged to continue sharing with the use of secondary questions and prompts to exhaust the topic. Interviews were record

Table 3. Semi-structured interview guide.

ed using a digital Dictaphone and transcribed verbatim by the first author for later analysis.

Data analysis

Orses

For all intervals, the sum was determined using MS Excel for each subsection in the inventory and then divided by the number of items in that subsection. This offered a mean score () for each section of the ORSES for each respondent, allowing a new mean score to be taken at the next interval offering a potential change in mean score per section between that interval.

To determine the statistical significance of any change in enjoyment and skill/competence (the two subsections of the ORSES), a Wilcoxon Signed Ranked Test was performed on the two pairs of responses pre, post, and post-3-month scores, using the ORSES. This test has been used in outdoor education to determine the significance of a programme (Dettmann-Easler & Pease, Citation1999). The test was conducted using a one-tail hypothesis at ρ ≤ .05 and ρ ≤ .01 levels of significance.

Interviews

A six-step reflexive thematic analysis was conducted on the post-session interviews (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019; Braun et al., Citation2018). The transcripts were read and re-read while listening to the audio recording, checked for accuracy to allow for immersion in the data (Morrow, Citation2005) and to ensure familiarisation with the data. The transcripts were then coded and recoded using the author’s experience as adventure sport participants and coaches to identify pertinent themes (Bryne, Citation2022). Coding occurred flexibly and organically occurring throughout the analysis (Bryne, Citation2022). NVivo 11 facilitated good visualisation of the coding within the transcripts throughout the reflexive process. Additionally, notes were used reflexively to aid comprehension. These coded units were then exported into Excel, allowing the data to be manipulated into lower-order subsequent themes. These themes were then revised and considered against the transcripts and final themes defined prior to the completion of the report.

The analysis of the ORSES and interview remained independent until the converging of the data sets.

Converging the data from ORSES and interviews

We treated the findings of the ORSES and thematic analysis as convergent and parallel. We analyse the two datasets, comparing them for aspects of convergence and divergence. Specifically, we examined the qualitative data for examples of enjoyment, accomplishment, skills, and competence development—the key aspects of the ORSES.

To aid trustworthiness, peer debriefings were conducted between the first and second author and then again between the first and a critical friend to reduce bias and improve the narrative of the findings, where the mid- and higher-order grouping process was repeated each time (Sparks, Citation1998). This allowed for the assessment of the degree of convergence and refinement of the names and, therefore, meanings of the mid and high-order themes. Peer debriefing acts as an audit of the data, improving the reliability of the analysis (Shenton, Citation2004), and reflecting the backgrounds of the authors who acted as critical friends who bring knowingness and relevance to the analysis (Braun et al., Citation2018).

Results and discussion

The results and discussion are divided into three sections. Firstly, we present and discuss the results of the ORSES, exploring the differences between the variables relating to self-efficacy, independence and demographic grouping. Secondly, we explore the qualitative data from the semi-structured interviews, examining the learner’s perspective on their independence as a result of the coaching they received. Then, thirdly, we draw together both sets of findings.

ORSES: Results

This section is broken into two sub-sections: accomplishment and enjoyment and skill and competence.

ORSES: Enjoyment and Accomplishment Analysis

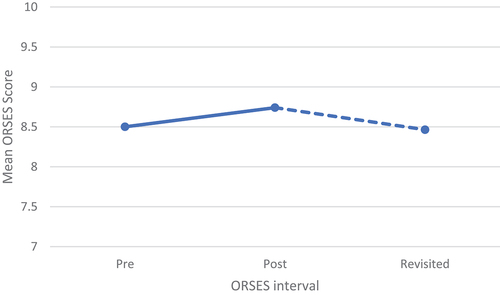

The first section of the ORSES explored perceptions of accomplishment and enjoyment. illustrates the mean score found in pre-programme, post-programme and revisited intervals.

The results of the Wilcoxon ranked signed test of enjoyment found no statistical significance between pre-post and post-3-month scores (ρ = .36 and .48 respectively), the mean individual change between pre- and post-measurements was an increase of .19 with a decrease in enjoyment of .13 between post and revisited measurements. Further exploration of the data was conducted to confirm whether this was reflected across discipline, age, experience and gender variables. No significant difference was found between demographics and, therefore, no difference in enjoyment as a result of the coaching programmes.

ORSES: Skill and Competence Analysis

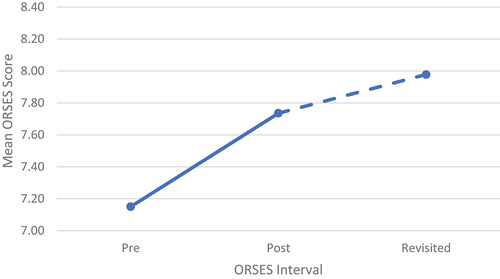

The second section of the ORSES explores participants’ perception of skill and competence concerning adventure sports. offers an illustration of the mean score of pre-programme, post-programme and revisited intervals for perceived skill/competence.

Across the whole sample, there was a significant increase in perception of skill and competency both between pre- and post-programme scores (ρ ≤ .01) and then between post and 3-month (ρ ≤ .01). The overall increase in perceived skill and competency was found to be significant at ρ ≤ .01 between pre-programme and post-programme and, post-programme and 3-month revisited stages. Further examination of the data reveals some differences between the variables in this sample (see ).

Table 4. Changes in ORSES skill/competency scores between intervals.

Male respondents seemed to gain their perceived increase in skills during the coaching programme (i.e. between pre and post) compared to three months later (i.e. between post and revisited intervals) with a mean () individual increase of .49 and .26 respectively. The increase between pre- and post-was found to be significant, ρ ≤ .05. Female learners perceived a larger increase in skill after the course (i.e. between post and 3-month) rather than during the coaching programme (

= .31 and 1.00 respectively for pre and post, the changes in the revisited score were found to be significant with ρ ≤ .01 in both intervals). These differences suggest that while coaching increases the perception of skills, there are notable differences in when and to what degree that perception is realised.

There was a notable difference between the responses of the mountain discipline group and the water sports group. Water-based responses reported an increase ( = .64) over the coaching programme (pre-post) with a similar increase three months later (

= .65), both proving to be significant increases (ρ ≤ .01). In contrast, an increase on mountain-based courses found (

= .50) on the course and increased again (

= .55) after three months. However, neither increase in mountain-based sports was found to be significant.

Between the age split, the under-50s experienced a relatively low increase in perceived skill by the end of the programme ( = .37), which was not significant, but the 50s and over reported the largest increase in perceived skill across any variable that was significant (

= 1.12 with ρ ≤ .05). After three months, the reported increase in skill according to the ORSES is reversed between the ages. The under 50s reported a significant increase in perceived skills (

= .70 with ρ ≤ .05) whereas the 50s and over experienced a small, not significant increase (

= .28). The older demographic appears to get their perceived increase more quickly than the younger learners.

Lastly, between experience, those with less than 10 years’ experience did not report a significant increase in their perception of skill over the coaching programme ( = .42) or after three months (

= .47). This contrasts with those with more than 10 years’ experience who reported a significant increase in skills by the end of the coaching programme (

= .89; with ρ ≤ .05) and a similarly sized increase following three months (

= .82) which was not significant. We can conclude that the more experienced learners gained a greater sense of perceived skill from their coaching programmes, both immediately and three months after, whereas those less experienced reported more modest increases.

ORSES: Understanding the Results

The perception of enjoyment did not appear to change, with the learners enjoying their participation before, during and after coaching. The critical point is that learners are not seeking coaching as a form of intervention to rediscover their motivation for participation; rather, learners appear motivated to develop independence and recognise that coaching is a part of, rather than the cause of, this development.

The findings offer a nuanced insight into learners’ development. Across the sample, there was a significant mean increase in perceived skill between both intervals. The findings suggest there are differences in the perceived skill gained during coaching and when that realisation is made between male and female learners. Male learners gained a more minor increase in perception during the coaching, while female learners experienced a greater overall increase in perceived skill at the revisited interval. Literature on the midterm differences in learning between men and women appears to be limited, but the findings presented here offer some pertinent questions for future research. Christian et al. (Citation2020) call for further research to aid the understanding of female perspectives in adventure sports as they are an underrepresented group. In seeking female perspectives of coach development, Weiss et al. (Citation1991) interviewed female coaches within a month of a coaching internship and found a perceived lack of confidence as part of their coaching competence. Our findings and those of Weiss et al. both sought female perspectives on sporting participation following a coached programme. However, differences in study design reveal potential differences in the time taken for female learners to realise their confidence. Conversely, a word of caution can be made regarding male learners in that a sudden rise in perceived ability that is not matched by their actual performance could have safety implications (Sherf & Morrison, Citation2019).

Both water and mountain-based disciplines reported an increase over both measurement intervals. However, water-based reported a slightly larger increase, which proved to be significant (see ). This raises questions about the impact of the environment on the development of perceived skills. The paddlesports coaches sampled appear to be training learners to trust and understand feedback and act on it. This point adds a dimension to the relationship between confidence and feedback (Sherf & Morrison, Citation2019) regarding the use of the environment as an opportunity for feedback that in turn, influences self-efficacy. However, no further literature could be found discussing the impact of the environment on skill development and confidence, suggesting a point for further study of hyper-dynamic environments.

The learners under 50 years of age gained a small increase in perceived skill initially, with a significant increase after three months. In contrast, the over 50s gained a significant increase over the coaching programme. Older participants who seek adventurous experiences reported that learning is a specific motivation to pursue such experiences, learning for the joy of learning (Sugerman, Citation2001). Equally, Frühauf et al. (Citation2017) suggest little difference between motivation, learning or participation between age ranges. While there are differences between age ranges in how coaching is received, we echo Hickman et al. (Citation2018)’s point that further research is needed to understand older participants.

More experienced learners reported nearly double the increase in perceived skill than the less experienced between both measurement intervals. The more experienced learners’ increase was found to be significant (ρ ≤ .05). The reason for this is unclear, but there is a reported relationship between a reduction of risk-taking behaviour with increased experience in adventure (Brymer, Citation2010; Frühauf et al., Citation2017; Llewellyn et al., Citation2008) which suggests that with experience and coaching, learners can realise their independence.

Interviews: Results

A reflexive thematic analysis was based on 347 codified units revealed from the transcripts. These were considered and grouped into 32 lower-order themes, which generated five mid-order themes and two higher-order themes. presents a summary of the thematic analysis with the mid-order themes that construct the two higher-order themes with two examples of codified units from the transcripts.

Table 5. Summary of the thematic analysis.

Table 6. Distribution of lower-order themes among interviewees.

Interviews: Understanding the Findings

This section is split into two, relating to the two higher-order themes, which are adventure sports confidence and independent learning.

Adventure sports confidence

This theme is constructed from nine lower-order themes that form three mid-order themes: (1) that participation is enjoyable, (2) trust in performance and, (3) trust in self.

Participation is enjoyable

The interviewees all reported enjoyment of their coaching sessions and participation in their chosen sport. Participant 10 explains that despite the challenges associated with participation, the experience is still enjoyable, ‘you might have been on the top end of our comfort levels, but we were all really happy and enjoying it out there, it’s great.’ Such enjoyment does not necessarily infer that the activity is simply fun or offers a hedonistic rush, a point made by multiple researchers (Hickman et al., Citation2018; Mackenzie & Brymer, Citation2020; Pomfret & Bramwell, Citation2016). Indeed, the challenges of the activity and learning may mean that coaching is not fun and, at times, Participant 08 reports ‘a sense of frustration,’ while noting that the whole experience was enjoyable. Outside of adventure, enjoyment of physical activity has been linked with an increase in self-efficacy among adolescents (Robbins et al., Citation2004) and college-aged women (Hu et al., Citation2007). Both studies suggest a positive relationship between enjoyment and self-efficacy. Hu et al. report that the ‘influence of self-efficacy appeared to be stronger when participants were exposed to a more challenging exercise,’ hinting that those adventurous activities could have a similar effect because of the explicit nature of challenge within the definition of adventure, as suggested by Participants 10 and 08 in these findings.

It is, therefore, not surprising that having a positive, enjoyable experience would translate to higher self-efficacy Bandura (Citation1977). Lewis et al. (Citation2016) expand on this point suggesting that interventions designed to improve and encourage long-term physical activity should focus on enjoyment over self-efficacy in order to encourage participation. Higher levels of enjoyment predicted higher levels of physical activity in the following six months. For adventure sports participants, enjoyment and self-efficacy are related and important for independence; enjoyment because otherwise, individuals would not participate, and self-efficacy so that they are confident enough to participate. Rather than prioritising enjoyment over self-efficacy, a more nuanced approach is required in adventure sports, and these findings place critical importance on the enjoyment of participation. This may, in part, be because of the ease with which participants can track their enjoyment, Participant 07 exemplifies this point:

I remembered a year and a half ago and I was really sort of shy and I felt awkward in the water and negative and you know that was just pulling me back and I wanted to join in and do it … now I do join in and feel good about that.

Participant 07’s experience of not feeling able to participate limits not only independence but also participation. The majority of adventure sports learners are recreational, it is the participants’ hobby and should be an enjoyable pursuit and, therefore, integral to an effective coached session. Focussing on independence, and enjoyable participation contributes to an overall sense of self-efficacy, with those interviewed suggesting that enjoyment is beyond a hedonistic rush and that challenging activities can be enjoyable.

Trust in performance

The majority of learners interviewed reported feeling pushed by their coach in either a physical or mental capacity beyond their own expectation of what they thought they could achieve in both mastery of performance and degree of challenge. Reports of being positively pushed beyond personal ability were found to be desirable for those who seek adventure sports coaching (Eastabrook & Collins, Citation2020). On selection of the task by the coach, 9 of the 10 interviewees had doubts about their technical or tactical ability but attempted the task, specifically, a challenging performance such as a climbing route or rapid, with the support of the coach. Participant 05 exemplifies this coach behaviour from the learner’s perspective: ‘I need that reassurance to know that I won’t make … [mistakes], I do know what I’m doing.’ This reassurance from the coach was the affirmation of ability. A supportive nature is an attribute of good coaches (Eastabrook & Collins, Citation2021). Consequently, the learners interviewed had a realisation of their own ability based on successful performance. Participant 02 explains the impact of this performance on her planned independent adventures: ‘I’ve done it before I know I can do it and I know how to do it.’ For Participant 02, having succeeded with the coach made her feel more able to do this independently, as her ability to adapt to the environment and find a valid solution had improved. The coach was able to match Participant 02’s level of skill with the challenge on offer to create an authentic, independent, and safe opportunity for her to perform in a meaningful way (Eastabrook & Collins, Citation2021).

Participant 05 describes a different aspect of trust in performance that is built over time and practice ‘working on the skills [over time] and becoming more efficient at them […] then more confident in my ability.’ Coaching took place within challenging changing conditions, requiring adaption of performance over the programme. The efficiency highlighted by Participant 05 describes the time taken to arrive at a valid solution, which is improved based on feedback from her coach. Additionally, Participant 05 suggests mastery of her performance positively affected her confidence, as Slanger and Rudestam (Citation1997) reported. Despite differences in risk and environment, this aspect of confidence has a commonality with sports coaching (Carson & Collins, Citation2011), suggesting that hard work is required to engage in deliberate learning. However, ultimately, with the guidance of the coach, the performance becomes robust. The experience might not be fun, but it is ultimately enjoyable.

Six out of the ten learners said that they desired validation of their ability from the coaching, primarily sought from the coaches in the form of feedback on performance. Learners were confident enough to perform independently but wanted affirmation that their solution was valid. This affirmation appears to be akin to a final sign-off for independence. Participant 10 illustrates the effect of this: ‘we probably would go and do that again now, as a result, whereas prior, we probably would have all been thinking, oh yeah, I’m not sure’. Similarly, 4 gained confidence ‘that everything I’d done was correct […] I didn’t have any doubts’ following a semi-independent performance under the supervision of her coach. The space to put the performance into an authentic environment and to gain positive feedback from her coach on her decisions and approach had a positive impact on the degree of trust she held in her performance. This insight from Participant 4 and Participant 10 places critical importance on the development of cognitive aspects of performance, such as decision-making, situational awareness and reflection.

Trust in Self

This aspect of sports confidence builds in the outdoor education pedigree of the adventure sports coach and broader notions of coaching to develop the individual receiving the coaching (Jones, Citation2006). As a result of the coaching, Participant 02 states, ‘I would be capable of doing it again.’ Participant 05 echoes this: ‘I feel really confident that I’d be able to do it.’ All the learners interviewed experienced a development in the degree to which they trusted themselves to operate and enjoy their sports. Participant 04 experienced validation of her ability after feeling independent with the coach in the background. She describes the value in ‘that self-assurance that I knew what I was doing.’ This is in alignment with Eastabrook and Collins (Citation2020) where learners sought coaching to validate their own abilities.

Participant 06 hints at an increased level of motivation to extend her level of challenge, reporting, ‘I’ve got more determination to get up those things [climbing routes],’ which is the result of being at the edge of her perceived ability. Participant 06’s point extends the aim of outdoor education, often referred to as character development (Stonehouse, Citation2011), to benefit her performance. Similarly, Participant 04 notes that developing her ability to effectively practice ‘has really helped with not just my confidence in trad climbing, but it’s kind of re-instilled my confidence with climbing as a whole.’ This highlighted both the wider benefits of developing the individuals as seen in outdoor activities (Lawton et al., Citation2017) and the related nature of the two higher-order themes.

In developing independence, adventure sports confidence is built from three parts. Firstly, to feel confident, learners realise that they are enjoying their participation because of the challenges it includes. Similarly, they need to trust their ability to perform, which is the ability to understand the environment, determine a valid solution and then realise their independence. All of which, we finally suggest, could be linked to heutagogy in this realm.

Independent Learning

This higher-order theme is constructed from two mid-order themes: what to learn and how to learn.

What to Learn

All those interviewed discussed what they had learnt as a result of coaching. Participant 08 has a holistic appreciation of what she is aiming for, ‘I’ve got a picture in my head, where I can be like, oh, that’s what it’s supposed to look like.’ This is echoed by Participant 09 who has ‘a better understanding’ of the desired performance. These learners have built up a context and comprehension of their desired performance. An understanding of the context for a skill is a key point in the challenge point framework (Guadagnoli & Lee, Citation2004), which recognises that creating authentic context alongside challenge is integral to learning. Equally, both the concepts of andragogy and heutagogy (Green & Schlairet, Citation2017) explicitly recognise context as a key aspect of the self-directed learning of adults. Learners indicate that their coaches are creating the context for their learning. This context is both the performance within the environment, as might be expected, but also the relevance of their own conception of adventure. The coaching the learners receive aligns with established notions of good teaching and learning.

Seven out of the ten learners interviewed reported a clearer understanding of the fundamental components of their discipline. Participant 02 highlights that after the context has been created, ‘[the coach] explained to me what to do and their approach to breaking things down.’ Once explained, Participant 09 recognised that, as a result of a coaching session, she ‘hopefully got the foundations engraved into me, it will become more natural [to put together].’ In contrast, where the coaches created an individualised context for learning, the use of mini-sessions appears to take a more coach-centred approach than before. This appears to be well accepted by those receiving the coaching, evidence of a harmonious coach-athlete relationship with both parties being happy to take the lead from each other, as established in the literature and support by Jowett and Slade (Citation2021).

Cassy makes a point regarding her understanding of the environment and decision-making: ‘I’m not just taking decisions based on my gut feeling, but more based on observations’. The coaching she received has given her insight into which environmental cues are important and how they might affect her performance. This describes a journey through the environment akin to a cognitive apprenticeship found in clinical development (Woolley & Jarvis, Citation2007; Wu et al., Citation2012) and proposed by Barry and Collins (Citation2021) in adventure sports coaches. In medical training, under the direct supervision of the trainer, learners can gain an experienced perspective on the environmental clues and their effects and, therefore, implications for performance. Owing to constant changes in the environment, such clues, with the necessary understanding, are needed to adapt the performance. Without an experienced coach to aid this process, the learner may require notable trial and error or may never gain a full understanding of the environment and its effect on performance. The theory of situational awareness supports the process to aid effective performance in adventure sports (Aadland et al., Citation2017). Cognitive apprenticeships provide context while stressing the importance to the learner being active in their learning (Backus et al., Citation2010). Backus et al. highlight that the coach models performance before the coach and learner develop that task. The learner later articulates this new task to gain confidence before undergoing learner-led reflection on its use. The last point offered by Backus et al. and highly pertinent for adventure sports is a period of exploration by the learner, linking to the next mid-order theme. The learner is transferring the new task into new situations, assuming more responsibility and gaining independence. Cognitive apprenticeships appear to be important in adventure sports coaching and require further investigation (Barry & Collins, Citation2021; Mees et al., Citation2020).

How to Learn

To be able to realise and develop their independence, those interviewed reported that they gained a better understanding of how to learn in response to what to learn, as discussed above. As Participant 10 highlights:

It was a great learning experience because if he [the coach] told me, then I would already have known, I wouldn’t have made the mistake. By learning it, of course, and next time that I have a similar situation, I will not make the same mistake.

This acknowledges the power of mistakes when learning. Learning from mistakes has been reported as a positive opportunity for learning because, in part, of the realness of the experience and feedback (White & Hardy, Citation1998) while too many mistakes could have a negative impact on learning. A positive view on mistakes is also highlighted by Participant 09 who is keen to ‘practise some of the things on flat water … if it was in a safe environment to me then I will quite happily go off and try it on my own.’ By developing an understanding of how to learn, Participant 09 is equipped to find suitable training venues, similar to the mini-session mentioned above, and gain value from those attempts. Participant 08 offers a nuanced view of the confidence in the ability to learn shown by Participants 09 and 10; she ‘probably wouldn’t be super confident about doing it again [post-coaching], but I mean I would, but I would figure it out.’ As a result, Participant 08 has confidence that she can influence her own performance. As highlighted by Eastabrook et al. (Citation2022), an aspect of adventure sports performance is in the construction of the performance rather than just the performance itself.

The learners interviewed recognised multiple sources of information beyond that of their coach in relation to themselves and their peers in alignment with a sophisticated view of knowledge (Schommer, Citation1994). Cassy supports this and highlights ‘it’s not just the coach, it’s the whole team, so it’s a constant ongoing process for me to observe them, the others, to discuss with them and just yeah, come to conclusions. Eastabrook and Collins (Citation2021) reported that coaches sought to encourage their learners to engage in their communities of practice and interaction with peers to continue their development. Cassy confirms that this has been successful; she is comfortable and able to draw meaning from her participation. The ability to draw meaning from experiences gives learners the ability to direct their own learning (Green & Schlairet, Citation2017). Coaches in the studies by Collins et al. (Citation2015) and Christian et al. (Citation2017) wanted to make themselves redundant, illustrating a desire to pass ownership of learning to the learner, a desired feature of coaches reported by coaches (Collins et al., Citation2015). Lastly, Participant 05 describes the importance of taking ownership of her development, linking it to her confidence to be independent:

If you’re climbing and somebody’s always there saying, ‘Put your foot there. Put your left foot there, put your right foot there,’ you’re never going to have that confidence to be able to go out on your own and be able to make that decision on your own.

The link between confidence and independence is explored further in the ORSES discussion, where the implication for independence is gained through the lens of the self-efficacy of those who undertook coaching.

The data suggests that independent learning is preparing learners to construct and reconstruct their fundamental skills in new situations. Coaches provide an authentic context for future skill development and the development of the learner’s fundamentals. Given the hyper-dynamic environment and the almost limitless ways the fundamentals can be constructed, instead of providing coached opportunities to apply these, the learners are being equipped with the ability to construct and reconstruct performances themselves with methods of validating and improving those solutions.

Contextualising the findings: a converging discussion

In converging the findings of the interviews and the ORSES, two further topics are pertinent: the transfer of ownership of learning and the nature of confidence.

Ownership of learning

In the interviews, learners reported that they felt more able to learn independently. They had developed learnacy (Claxton, Citation2003). Such a position reflected an emerging epistemology. Notably, the learner appeared to be developing a sophisticated view of knowledge akin to their adventure sports coaches. An epistemological alignment or coherence between the coach and learners’ views of what needed to be learnt and how it could be learnt. This appeared to extend the notion of an epistemological chain further, stretching beyond the coach and their practice but also to the values of the learner. This requires further specific investigation. It seemed unclear if this position was a product of good coaching (Collins et al., Citation2015) or the understanding of adventure sports performance and the environment (Christian et al. (Citation2020). The learners reported that they felt more able to learn on their own, knowing what and how they needed to practise, continuing their development independent of the coach as a movement towards greater independence.

These findings from the interviews appear supported by the findings of the ORSES. Not only are the learners developing skills and competency over the coaching course, but they are also continuing to develop at a similar rate following and independently following the course. The coaches appeared to be creating not only independent performers but also independent learners. The alignment between these interviews and ORSES supports the point from the literature that coaches are trying to make themselves redundant Collins and Collins (Citation2021). However, we conjecture that a more accurate position might be that coaches are equipping their learners to take ownership of their development and participation- a more fundamental aspect of independence. Rather than developing each learner towards a personal concept of adventure, the coaches are preparing the learners to take future action in their pursuit of independent, adventurous experiences. It seems that performance may be conceived of as becoming independent rather than the degree of adventurousness, though this requires further investigation.

Nature of confidence

The findings for the enjoyment and accomplishment section of the ORSES offer insight into what learners seek from coaching. Confidence has been highlighted in previous studies into adventure sports (Eastabrook & Collins, Citation2021; Ellmer & Rynne, Citation2016; Lynch & Dibben, Citation2016). A desire for increased confidence from coaching could stem from a lack of enjoyment, a relationship tentatively highlighted by Curran et al. (Citation2015). However, this does not appear to be the case here, as learners are enjoying their participation at all ORSES intervals and within the interviews. Therefore, despite a focus on wanting to develop confidence and motivation to develop confidence after coaching, this process should not be viewed solely as an intervention to reignite enjoyment. Learners recognise that the hard work they are putting into their development is enjoyable because of the adventures and independence it affords them. Coaching is an opportunity to check in with a coach on the route to greater independent performance. In this respect, developing confidence is not necessarily the starting or restarting point of a coaching relationship. Instead, it appears also to be an understanding of confidence when considering the situational comprehension highlighted by Eastabrook et al. (Citation2022). Learners report in the interviews that their levels of enjoyment remain high throughout coaching and participation, their enjoyment stemming from the growth of confidence in their abilities. Development independence stems from confidence, which of itself is enjoying. This would seem to align with notions of being in control rather than the thrill-seeking that is perhaps associated with being at the limit of control. A coach’s ability to empower learners could be of value to coaches in other domains, something that would need further research.

Conclusion

The findings from this mixed study have demonstrated that these learners are developing independence, as intended by their coaches. The ORSES offers a framework within which the semi-structured interviews provide richness and depth to the learners’ experience. As independence grows via skill development, so do confidence and self-efficacy. The findings from the ORSES suggest that learners are gaining self-efficacy during and continue after the coaching. This growth stemmed from the learners knowing how and what to learn- an intention of the coach’s strategies for development. The learners are learning to be independent practically, as learners and as adventure sports practitioners. The quantitative findings reveal differences between sex and activity (water- and mountain-based) that would be worthy of further investigation.

The overall findings demonstrate that these participants developed towards greater independence, growing in confidence, skill and ability to learn without the ‘crutch’ of a coach. Our findings extend the work by Eastabrook et al. (Citation2022). In addition, our findings reinforce the concept of an epistemological chain identified by Collins et al. (Citation2015) and highlight the need for a coherent epistemological link between learner and coach as identified by Collins and Collins (Citation2021), further adding to the finding by Mees et al. (Citation2022).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chris Eastabrook

Dr Chris Eastabrook is the Head of Centre of Bryntysilio Outdoor Education Centre in Llangollen, Wales, having previously worked in mainstream and higher education and as a coach and coach developer. Chris is a pracademic focusing on both the educative role of coaches and the use of coaching within educative learning objectives, specifically in adventure and outdoor settings.

Loel Collins

Dr Loel Collins teaches at the University of Edinburgh in the Institute of Sport, Physical Education and Health Sciences, Moray House School of Education and Sport. He research interest lie in investigating the specifics of coaching adventure sports, coach judgement and decision-making in dynamic environments and coach development.

Robin D. Taylor

Dr Robin D. Taylor is an Assistant Professor in Elite Performance at Dublin City University, Ireland. Robin’s has published in the areas of coaching and talent development and has worked with a range of stakeholders as an educator, coach and consultant across UK and Irish sport.

Pamela Richards

Dr Pamela Richards is a Reader in Decision-Making and Interoperability (University of Central Lancashire). Pam is a world qualified, High-Performance Coach, and has coached the national team for 19 years (field hockey). Pam is also a Chartered Psychologist, Associated Fellow (AFBPsS) and supervises doctorial students in high-pressurised team decision-making.

References

- Aadland, E., Vikene, O. L., Varley, P., & Moe, V. F. (2017). Situation awareness in sea kayaking: Towards a practical checklist. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 17(3), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2017.1313169

- Backus, C., Keegan, K., Gluck, C., & Gulick, L. M. V. (2010). Accelerating leadership development via immersive learning and cognitive apprenticeship. International Journal of Training and Development, 14(2), 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2419.2010.00347.x

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Barry, M., & Collins, L. (2021). Learning the trade–recognising the needs of aspiring adventure sports professionals. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2021.1974501

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative research in Sport. Exercise & Health, 11 (4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2018). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103

- Brymer, E. (2010). Risk-taking in extreme sports: A phenomenological perspective. Annals of Leisure Research, 13(1–2), 218–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2010.9686845

- Bryne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56, 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Carson, H. J., & Collins, D. (2011). Refining and regaining skills in fixation/diversification stage performers: The five-A model. International Review of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 4(2), 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2011.613682

- Christian, E., Berry, M., & Kearney, P. (2017). The identity, epistemology and developmental experiences of high-level adventure sports coaches. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 17(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2017.1341326

- Christian, E., Hodgson, C. I., Berry, M., & Kearney, P. (2020). It’s not what, but where: How the accentuated features of the adventure sports coaching environment promote the development of sophisticated epistemic beliefs. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 20(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2019.1598879

- Christian, E., Kelly, J. S., Piggott, L. V., & Hoare, J. (2020). A demographic analysis of UK adventure sports coaches. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2020.1854099

- Claxton, G. L. (2003). Learning is learnable (and we ought to teach it). In T. N. C. O. Education (Ed.), Learning to succeed: The Next Decade (pp. 30–35). University of Brighton.

- Collins, D., Abraham, A., & Collins, R. (2012). On vampires and wolves - exposing and exploring reasons for the differential impact of coach education. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 43(3), 255–271.

- Collins, L., & Brymer, E. (2020). Understanding nature sports: A participant centred perspective and its implications for the design and facilitating of learning and performance. Annals of Leisure Research, 23(1), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2018.1525302

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2021). Managing the cognitive loads associated with judgment and decision-making in a group of adventure sports coaches: A mixed-method investigation. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2019.1686041

- Collins, L., Collins, D., & Grecic, D. (2015). The epistemological chain in high-level adventure sports coaches. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 15(3), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2014.950592

- Collins, D., Taylor, J., Ashford, M., & Collins, L. (2022). It depends coaching–the most fundamental, simple and complex principle or a mere copout?. Sports Coaching Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2022.2154189

- Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. L. (Eds.). (2011). Choosing a mixed methods design. In Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed. pp. 53–106). Sage. https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/10982_Chapter_4.pdf

- Curran, T., Hill, A. P., Hall, H. K., & Jowett, G. E. (2015). Relationships between the coach-created motivational climate and athlete engagement in youth Sport. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 37(2), 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2014-0203

- Deakin, H., & Wakefield, K. (2014). Skype interviewing: Reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research, 14(5), 603–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794113488126

- Dettmann-Easler, D., & Pease, J. L. (1999). Evaluating the effectiveness of residential environmental education programs in fostering positive attitudes toward wildlife. The Journal of Environmental Education, 31(1), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958969909598630

- Durán-Sánchez, A., Álvarez-García, J., & Del Río-Rama, M. D. L. C. (2020). Nature sports: State of the art of research. Annals of Leisure Research, 23(1), 52–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2019.1584535

- Eastabrook, C., & Collins, L. (2020). Why do individuals seek out adventure sport coaching? Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 20(3), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2019.1660192

- Eastabrook, C., & Collins, L. (2021). What do participants perceive as the attributes of a good adventure sports coach? Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 21(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2020.1730207

- Eastabrook, C., Taylor, R. D., Richards, P., & Collins, L. (2022). An exploration of coaching practice: How do high-level adventure sports coaches develop independence in learners? International Sport Coaching Journal 10(2), 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2021-0087

- Ellmer, E., & Rynne, S. (2016). Learning in action and adventure sports. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 7(2), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2016.1196111

- Ewert, A., Gilbertson, K., Luo, Y.-C., & Voight, A. (2013). Beyond because it’s there: Motivations for pursuing adventure recreational activities. Journal of Leisure Research, 45(1). https://doi.org/10.18666/JLR-2013-V45-I1-2944

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013, December). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt 2), 2134–56. Epub 2013 Oct 23. PMID: 24279835; PMCID: PMC4097839. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Frühauf, A., Hardy, W. A. S., Pfoestl, D., Hoellen, F.-G., & Kopp, M. (2017). A qualitative approach on motives and aspects of risks in freeriding. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(November), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01998

- Green, R. D., & Schlairet, M. C. (2017). Moving toward heutagogical learning: Illuminating undergraduate nursing students’ experiences in a flipped classroom. Nurse Education Today, 49, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.11.016

- Guadagnoli, M. A., & Lee, T. D. (2004). Challenge point: A framework for conceptualizing the effects of various practice conditions in motor learning. Journal of Motor Behaviour, 36(2), 212–224. https://doi.org/10.3200/JMBR.36.2.212-224

- Hickman, M., Stokes, P., Gammon, S., Beard, C., & Inkster, A. (2018). Moments like diamonds in space: Savouring the ageing process through positive engagement with adventure sports. Annals of Leisure Research, 21(5), 612–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2016.1241151

- Hu, L., Motl, R. W., McAuley, E., & Konopack, J. F. (2007). Effects of self-efficacy on physical activity enjoyment in college-aged women. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 14(2), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03004174

- Jones, R. L. (Ed.). (2006). How can educational concepts inform sports coaching?. In The sports coach as educator (pp. 21–31). Routledge.

- Jowett, S., & Slade, K. (2021). Understanding the coach-athlete relationship and the role of ability, intentions and integrity. In C. Heaney, N. Kentzer, & B. Oakley (Eds.), Athletic development: A psychological perspective (pp. 1–25). OPEN UNIVERSITY publication Chapter.

- Lawton, E., Brymer, E., Clough, P., & Denovan, A. (2017). The relationship between the physical activity environment, nature relatedness, anxiety, and the psychological well-being benefits of regular exercisers. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(JUN). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01058

- Lewis, B. A., Williams, D. M., Frayeh, A. L., & Marcus, B. H. (2016). Self-efficacy versus perceived enjoyment as predictors of physical activity behaviour. Psychology & Health, 31(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.040

- Llewellyn, D. J., Sanchez, X., Asghar, A., & Jones, G. (2008). Self-efficacy, risk taking and performance in rock climbing. Personality & Individual Differences, 45(1), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.001

- Lynch, P., & Dibben, M. (2016). Exploring motivations for adventure recreation events: A New Zealand study. Annals of Leisure Research, 19(1), 80–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2015.1031804

- Mackenzie, S. H., & Brymer, E. (2020). Conceptualizing adventurous nature sport: A positive psychology perspective. Annals of Leisure Research, 23(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2018.1483733

- Mees, A., & Collins, L. (2022). Doing the right thing, in the right place, with the right people, at the right time; a study of the development of judgement and decision-making in mid-career outdoor instructors. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2100800

- Mees, A., Sinfield, D., Collins, D., & Collins, L. (2020). Adaptive expertise – a characteristic of expertise in outdoor instructors? Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 25(4), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1727870

- Mittelstaedt, R. D., & Jones, J. J. (2009). Outdoor recreational self-efficacy: Scale development, reliability and validity. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 1(1), 97–120. https://doi.org/10.7768/1948-5123.1006

- Morgan, D. L. (2014). Pragmatism as a Paradigm for Social Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(8), 1045–1053. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800413513733

- Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative Research in counselling Psychology. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 52(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

- Olive, R. (2020). Thinking the social through myself: Reflexivity in research practice. In B. Humberstone & H. Prince (Eds.), Research Methods in Outdoor Studies (pp. 121–129). Routledge.

- Olsen, W. (2014). Triangulation in social Research: Qualitative and quantitative methods can really be mixed. In M. Holborn (Ed.), Developments in sociology (pp. 1–30). Causeway Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315838120

- Palincsar, A. S. (1998). Social constructivist perspectives on teaching and learning. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 345–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.345

- Pomfret, G., & Bramwell, B. (2016). The characteristics and motivational decisions of outdoor adventure tourists: A review and analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(14), 1447–1478. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.925430

- Robbins, L. B., Pis, M. B., Pender, N. J., & Kazanis, A. S. (2004). Exercise self-efficacy, enjoyment, and feeling states among adolescents. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 26(7), 699–715. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945904267300

- Schommer, M. (1994). Synthesizing epistemological belief research: Tentative understandings and provocative confusions. Educational Psychology Review, 6(4), 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02213418

- Shenton, A. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(August), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-618X.2000.tb00391.x

- Sherf, E. N., & Morrison, E. W. (2019). I do not need feedback! Or do I? self-efficacy, perspective taking, and feedback seeking. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(2), 146–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000432

- Slanger, E., & Rudestam, K. E. (1997). Motivation and disinhibition in high-risk sports: Sensation seeking and self-efficacy. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2193

- Sparkes, A. C. (1998). Validity in qualitative inquiry and the problem of criteria: Implications for sport psychology. The Sport Psychologist.

- Sport England. (2022). Active Lives | Results. https://activelives.sportengland.org/Result?queryId=19210

- Stonehouse, P. (2011). The rough ground of character: A philosophical investigation into character development on a wilderness expedition through a virtue ethical lens. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.7768/1948-5123.1109

- Sugerman, D. (2001). Motivations of older adults to participate in outdoor adventure experiences. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 1(2), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670185200051

- Varley, P., & Semple, T. (2015). Nordic slow adventure: Explorations in time and nature. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(1–2), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1028142

- Weiss, M. R., Barber, H., Sisley, B. L., & Ebbeck, V. (1991). Developing competence and confidence in novice female coaches: II. Perceptions of ability and affective experiences following a season-long coaching internship. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 13(4), 336–363.

- White, A., & Hardy, L. (1998). An in-depth analysis of the uses of imagery by high-level slalom canoeists and artistic gymnasts. The Sport Psychologist, 12(4), 387–403.

- Willis, G. (2005). Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Sage.

- Woolley, N. N., & Jarvis, Y. (2007). Situated cognition and cognitive apprenticeship: A model for teaching and learning clinical skills in a technologically rich and authentic learning environment. Nurse Education Today, 27(1), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2006.02.010

- Wu, P.-H., Hwang, G.-J., Su, L.-H., & Haung, Y. (2012). A context-aware mobile learning System for supportive cognitive apprenticeships in nursing skills training. Educational Technology & Society, 5(1), 223–236.