ABSTRACT

A comprehensive national study investigated education outside the classroom (EOTC) in Aotearoa New Zealand and revealed the negative impact of safety legislation on EOTC. To understand the work the safety legislation does, we analysed data from a survey and interviews, and developed a framework of spheres of responsibilities: student safety; legislative requirements; staff competence; and paperwork. Findings show that health and safety legislation has reduced the amount of EOTC in many schools. There was strong evidence that educators cared for the learning and safety of students, and this generated anxiety for staff. This anxiety was further heightened by threats of personal legal liability. Instead of threats, some respondents felt that teachers’ commitment to student learning through EOTC should be celebrated. Other respondents strongly continued to support EOTC. The contribution of school culture, EOTC champions, effective systems and teacher education are seen as pivotal to reducing anxiety and sustaining EOTC.

Introduction

Since previous education outside the classroom (EOTC) research in Aotearoa New ZealandFootnote1 (Haddock, Citation2007a, Citation2007b) there have been notable changes to the legal context. In 2014 the Vulnerable Children Act, now titled the Children’s Act (CA), was passed to better protect children. In addition, there was a clarification of the Health and Safety at Work Act in 2015 (HSAWA) which indicated that individual school leaders and teachers could be prosecuted if found legally liable for an incident either at school or during EOTC. Concomitantly, anecdotal evidence suggested that these legislative changes were having a ‘chilling’ effect on the provision of EOTC. This paper draws on a comprehensive national EOTC study (Hill et al., Citation2020) which investigated the effects of a range of factors, including legislative changes, on EOTC in schools.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the generic term Education Outside the Classroom (EOTC) is used to describe ‘curriculum-based learning and teaching that extends the four walls of the classroom’ (Ministry of Education, Citation2016, p. 1). EOTC is rich and varied in scope, occurs across the spectrum of subjects, and may involve learning opportunities in the school grounds through to international travel and low to higher risk activities. As such, EOTC ranges ‘from a museum or marae [Māori place used for social and ceremonial fora] visit to a sports trip, an outdoor education camp, a field trip to the rocky shore, or a visit to practise another language’ (Ministry of Education, Citation2016, p. 1). Our earlier work (Hill et al., Citation2020) revealed primary schools tended to make use of more local EOTC experiences with the exception of residential outdoor education camps, while secondary schools often incorporated trips further afield for a variety of subject areas. Overall, health and physical education (including outdoor education) had the highest frequency of EOTC with 92% of schools having at least one HPE-related EOTC event per term. In science, social science, the arts, English, and integrated studies, 53–63% of schools had at least one EOTC event per term.

Although EOTC varied among subject areas and school types, respondents unanimously saw it to be an important part of school life in Aotearoa New Zealand. In particular, EOTC provided a unique contribution to enhancing student learning and engagement, to enriching curriculum, to developing social relations and connections, and proffered a valued ‘sense of something new’ (Hill et al., Citation2020; North et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, a number of challenges to the quality and quantity of EOTC were reported. Costs and resourcing, time constraints, workload issues, staff competence, and the impacts of legislation featured strongly (Hill et al., Citation2020; Watson et al., Citation2020). Schools’ experiencing of these was complex and not ‘shared equally across all school contexts’ (Hill et al., Citation2020, p. 45).

This paper is the first in a series of two examining some of these challenges, honing in specifically on the impacts of legislation on EOTC provision in Aotearoa New Zealand. Here, in the first paper, we introduce and examine pertinent legislation and its impacts on EOTC provision, with the companion paper having a particular focus on the paperwork and documentation used in the planning of EOTC learning experiences and programmes. We set the scene by beginning with an introduction to EOTC policies and legislation in Aotearoa New Zealand, targeting the CA (Citation2014) and HSAWA (Citation2015). Attention then turns to outlining the ‘spheres of responsibility’ that we are using as a framing device for the paper. One sphere is directly concerned with student safety, other spheres include meeting legislative requirements, teacher competence and finally paperwork and compliance which is explored in the companion paper. We then describe the methodology used in the national study and present key findings from the quantitative and qualitative data illustrating the impacts of legislation on EOTC, before finishing with implications.

EOTC policies and legislation

Student learning is recognised to be the ‘heart’ of EOTC, and safety and learning are closely entwined (Ministry of Education, Citation2016). While the work of educators in planning for student learning and safety is relevant to all educational experiences, EOTC presents additional challenges due to the less predictable nature of the environments and settings compared to classroom teaching. This moral and social responsibility of teachers to students can be considered a ‘principled professionalism’ (Goodson, Citation2000). Student learning and safety in all educational contexts including EOTC is arguably a fundamental focus of educators, and rests on a moral professional responsibility that the expectations of policy and legislation augment.

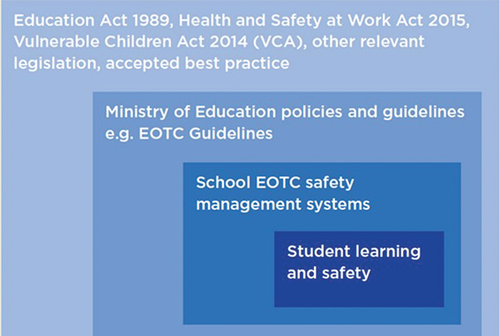

Since 1989, schools in Aotearoa New Zealand have been delegated high levels of autonomy in terms of governance and financial decision-making through elected school boards of trustees (BOT) made up of parents and the school principal acting as chief executive. The BOT has overall responsibility for strategic direction, employment of staff, financial and property management, policies and procedures and health and safety while the principal’s role is to manage and also be accountable for all aspects of the day‐to‐day running of the school. The EOTC Guidelines (Ministry of Education, Citation2016) provide a key framework for school staff and the BOT about their responsibilities for different levels of systems, policies and legislation in EOTC provision ().

Figure 1. The policy and legal framework surrounding EOTC (Ministry of Education, Citation2016).

Unsurprisingly, student learning and safety are seen to be inextricably interconnected, and in turn, are centralised in this policy and legal framework (Ministry of Education, Citation2016). Strong links are made to student needs, desired learning outcomes and the national curriculum (ibid), and cultural and environmental safety are also included. Surrounding this are the school safety management systems which in turn, are nested within the policies and guidelines of the Ministry of Education and finally, the applicable legislation and accepted best practice.

The implications of the legislation in the outer layer are further unpacked in the EOTC Guidelines. This includes spelling out the governance expectations, lines of accountability and responsibilities of different groups involved in EOTC (including for example the EOTC coordinator at a school, person in charge of an event, activity leaders, or students). The potential for prosecution of individuals is also identified:

If there is an incident during an EOTC event, a board may be held accountable whether the incident is caused by the actions or omissions of a teacher, volunteer assistant, student, or provider contracted by the board … if there is a failure to carry out due diligence; or to develop and follow policies and procedures which keep students, staff, and volunteers safe during the event; then the board, and/or its officers (e.g. principal), and/or its workers may be liable to prosecution.

Two recent pieces of legislation, the Children’s Act (Citation2014) and the Health and Safety at Work Act (Citation2015) are specifically discussed in the EOTC Guidelines and are critical to consider here.

Children’s act and health and safety at work act

The Children’s Act (Citation2014) (CA) was intended to safeguard children when interacting with adults. The CA requires people employed or engaged in work that involves regular or overnight contact with children to be safety checked (see Section 2.14 of the CA for details). There is an emphasis on protection, but also a focus on allowing young people to flourish and empowering them to make their own decisions. In order to achieve these outcomes BOT must adopt a child protection policy and ensure that a copy of the policy is available. The CA requires that paid employees undergo police checks, but this has also become accepted practice for parent helpers and volunteers in schools (Ministry of Education, Citation2016). Therefore many schools now require parent helpers and others working with students to have completed a police check for a criminal record, identity, and reference checks, and a risk assessment. This is particularly important for EOTC where parent helpers are often used to support safe ratios, even more so for overnight or residential events.

The second piece of legislation to consider here is the (Health and Safety at Work Act, Citation2015) (HSAWA) which sets out its purpose as ensuring that everyone who goes to work comes home healthy and safe. To achieve this end, the HSAWA firstly ensures everyone has a role to play and that responsibilities are made clear. The management of risks in workplaces is required, as is the expectation that workers will actively participate in health and safety processes. Although there is flexibility in how these health and safety risks are managed, serious consequences of fines, imprisonment and disqualification can be imposed for breaches of the Act. The EOTC Guidelines (Ministry of Education, Citation2016) further clarify that a BOT’s obligations, ‘so far as is reasonably practicable,’ are to ensure work environments are without risks to health and safety; and to provide adequate facilities, information, training and supervision (p. 54). More specifically in EOTC, this should mean that risks of serious harm are managed, safe equipment provided for use, competent staff involved, and emergency procedures planned and employed if needed.

From this brief appraisal we can see that health and safety legislation is intended to be clear, explain roles and responsibilities, and engage workers in being actively involved in managing risks. Simply put, the legislation works towards the uncontroversial outcome of making sure those who go to work or to school-related activities ‘come home healthy and safe.’ How this is enacted when the legislation is ‘placed’ into sociocultural contexts is however critical for its effectiveness. As Suchman and Edelman (Citation1996) suggest, the intentions of law-makers are always mediated through individuals and communities, and the cultures and environments in which they are interpreted and enacted at any given time. The effectiveness of laws in achieving their intended objectives therefore become supported or undermined by a welter of social processes.

Impacts of legislation in educational contexts

As noted, health and safety at work legislation is designed to reduce injuries and fatalities through prompting organisations and individuals to take a positive and proactive approach to harm prevention. Gunningham (Citation1999, p. 195) argues that health and safety legislation can ‘stimulate modes of reflection’ which support harm prevention. Other scholars however contend a diversity of outcomes can occur in the enactment of legislation including: the enhancement of safety; the undermining of trust; and the twisting of compliance into symbolic rituals and ‘superficial compliance’ (Suchman & Edelman, Citation1996, p. 912). As Selznick (Citation1996, p. 275) notes, this makes it important to ‘identify the conditions and processes that frustrate ideals or, instead, give them life and hope.’

Recent research in Aotearoa New Zealand about enacting legislation includes Bennett et al.’s (Citation2022) auto-ethnographic examination of the operationalisation of the CA by three male educators. Their research highlighted the anxiety of males working with younger children and girls, and that sport coaches and physical education teachers could become framed as ‘dangerous, in danger and observers of and for danger’ (p. 417). These authors argued the process of police vetting to work with children asked applicants questions which highlighted the dangerous nature of adults working with children who were framed as vulnerable. In addition, the role of educators became to avoid situations where they could be accused of inappropriate behaviour and therefore, they themselves were ‘in danger,’ and to be on the lookout for others who might pose a danger to their charges. In brief, these teachers felt there was a lack of trust or a suspicion of them in their roles and in response, became cautious, and restricted their pedagogical approaches. As socio-cultural theories suggest, inadvertent outcomes can result from well-intentioned laws implemented in particular cultures and environments (Suchman & Edelman, Citation1996).

Health and safety at work legislation has had similar impacts on teachers in England. Murphy (Citation2022) explored the law in educational settings and found that it generated a low trust culture that saw trust in people’s judgement as a risk which should be avoided. Murphy argued that as a consequence, educators lost confidence in themselves, lost the ability to take rational action, and lost confidence in the system. Legal threats created a type of anxiety as risking trust was seen to be ‘open[ing] oneself up to unnecessary danger, for example, in the shape of accusations of professional incompetence or malpractice’ (Murphy, Citation2022, p. 9). For some teachers therefore, and despite its intent, health and safety legislation may result in feelings that trust has been eroded, create anxieties about people’s professional roles and their abilities to carry out their work effectively, and reduce confidence in their judgement.

Framework for our discussion

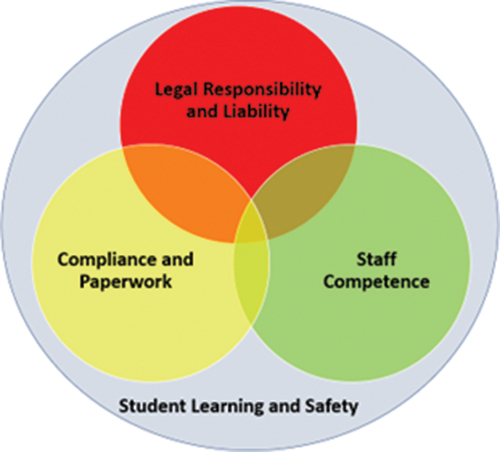

Before discussing the methodology of the national study we clarify the framing of four spheres of responsibilities for educators and school leaders (). In this framing, educators’ and school leaders’ four interconnected and overlapping ‘spheres of responsibility’ are invoked, with the outer and most critical sphere being directly focused on student learning and safety during EOTC learning activities. This is encompassed by Goodson’s (Citation2000) work on ‘principled professionalism’ which highlights the moral and ethical duties of educators to students and includes the ‘discretionary judgement concerning the issues of teaching, curriculum and care that affect one’s students … [and] the skills and dispositions that are essential to committed and effective caring’ (p. 187). Another sphere of responsibility is to ensure that EOTC operates within the law and meets legal expectations. School leaders are responsible for ensuring that staff in charge of EOTC are competent and experienced. In addition, in our companion paper, is the sphere of responsibility addressing the expectations of compliance and paperwork.

Methodology

The data which this article draws on are from a national study conducted in 2018 which investigated EOTC in schools across Aotearoa New Zealand through the perspectives of principals, EOTC coordinators, teachers, and students. This article focuses on data related to the research question examining how various factors influence the provision (quantity and quality) of EOTC.

Overall, the EOTC study employed an explanatory sequential mixed methods research approach, which blended initial survey-based quantitative and qualitative data with subsequent interviews (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2017). The benefits of this approach support statistical insights from survey data with in-depth perspectives from different school contexts throughout Aotearoa New Zealand. This article draws on data from the phase one survey, National EOTC Questionnaire (NEOTCQ) containing a mix of quantitative (Likert scale) and qualitative (open ended) questions and the follow up phase involving individual and focus group interviews with school leaders, teachers, students and providers of EOTC experiences (for example museums).

The phase one NEOTCQ was an online Qualtrics questionnaire adapted by the research team from the work of Mannion et al. (Citation2015). Content validity was established through feedback from an expert group including representatives of principals’ organisations and academics with relevant expertise within Aotearoa New Zealand. The NEOTCQ was open for five weeks, with initial invitation emails plus two follow-up emails sent to all primary (PS), intermediate (middle school) (IS), secondary (SS), and composite (CS) school contacts on the New Zealand Ministry of Education website. Invitation emails were also sent to EOTC coordinators who were registered on the National EOTC Coordinator Database. In total the NEOTCQ had 523 respondents which included Principals (60%), EOTC coordinators (22%), and teachers and curriculum leaders (18%). The overall response rate (RR) was 21%, which is acceptable for a national survey of this type.

Twenty (20) schools volunteered to participate in the follow-up interview phase of the study through self-identification via a question in the NEOTCQ. All schools who volunteered were visited in person (except for two cases where interviews were conducted online using Zoom due to logistic and remoteness). For each school visit, staff who were available at the time were individually interviewed, whilst student interviews were exclusively through focus groups. Students interviewed ranged between 6 and 18 years of age. In five schools, there were no student focus groups as only staff were available at that time. We acknowledge that participants self-selected for the study, and the data is likely to reflect the views of people, schools and organisations with an interest in EOTC (Barfod & Bølling, Citation2022).

The study was conducted in ways which upheld the four key principles for ethical research in Aotearoa New Zealand: Respect for people, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Ethics approval was gained from the ARA Institute of Canterbury human research ethics committee. The data sets were initially analysed separately with quantitative data undergoing descriptive analysis to reveal the percentage of agreement or disagreement with certain statements in the NETOCQ. The qualitative data was analysed thematically through a coding process to identify key themes or patterns from participants’ perspectives (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Integrated analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data patterns was then conducted collaboratively by multiple members of the research team to identifying the major trends and themes in an inductive and recursive way (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2017).

Integrated analysis revealed that the strongest influences on EOTC were health and safety legislation, compliance and paperwork, risk aversion of school leaders, and considerations for student safety and learning. In this paper, we draw on participant experiences and perspectives most relevant to those key themes to better understand the impact of these influences on EOTC provision. The trustworthiness of the analysis is demonstrated by weaving participant quotes into the interpretation of findings and by using illustrative examples to thickly describe the data.

Findings

Concerns about the effects of health and safety legislation on EOTC came through very strongly in both the quantitative and qualitative data. Firstly, we present an informative overview through the quantitative data, before we elaborate through the qualitative data.

Analysis of quantitative data suggests many factors were seen as problematic by considerable numbers of research participants. In particular, two factors, paperwork and workload and the new health and safety legislation, were seen as impacting negatively on EOTC quantity by 44% of the responders ().

Table 1. Barriers and their perceived impact on EOTC.

Thirty percent of respondents felt police vetting of volunteers decreased the quantity of EOTC offered as a flow on effect from the Children’s Act (Citation2014). Likewise, 35% indicated that school leaders and BOTs have become more risk averse resulting in less EOTC. While these are worrying numbers, it is also evident that a substantial percentage of other schools (34% to 39%) did not consider these factors had an impact. Collectively, there is strong evidence that legislation is having a detrimental impact on the quantity of EOTC in many schools.

School type and decile analysis of factors affecting the quantity of eOTC

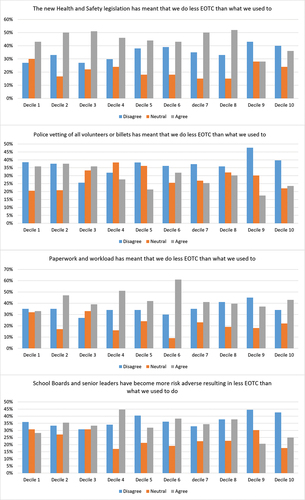

To further understand the problem, descriptive statistical analyses were conducted to see if both school type and decile had an influence. Decile was a funding mechanism used at the time to support schools in areas of low socio-economic status (SES). Schools are rated from 1 to 10 with 1 being communities with low SES and 10 being wealthier communities with high SES (see Ministry of Education, Citationn.d.). The findings showed that schools from decile 1 to 8 shared similar patterns of responses, whereas for decile 9 and 10 schools the pattern was reversed. For example, 41% of decile 9 and 34% of decile 10 schools disagreed that Health and Safety legislation reduced the quantity of EOTC (with agreement at 27% and 31%, respectively). Further analysis shows that the effects of the health and safety legislation were more pronounced for low decile schools (M = 3.38, SD = 1.25) compared to high decile schools (M = 3.06, SD = 1.14), t (307) = 2.35, p = 0.02, r = .13 (). For decile 9 and 10 schools therefore, Health and Safety legislation was perceived as a less significant barrier to EOTC quantity than schools from other deciles (see ).

A similar trend can be found for School boards and senior leaders becoming more risk averse and Police vetting (). From these data, it is reasonable to conclude that decile 9 and 10 schools were less impacted than lower decile schools. Interestingly, there was no obvious pattern in paperwork and workload between the decile levels.

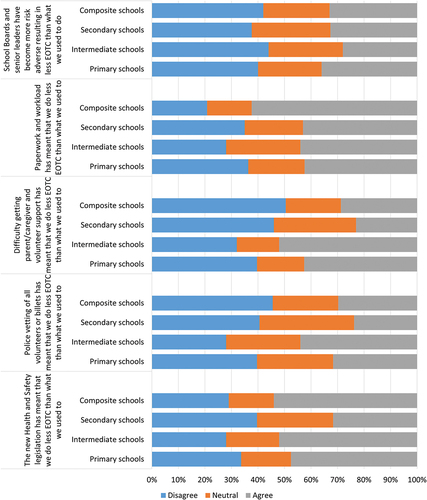

Given the differences in some deciles, analysis was also conducted based on school type and was found to have an influence on each of the statements as shown below (see ).

New Health and Safety legislation reduces EOTC had more agreement than disagreement for Primary (New Entrant to Year 6), Intermediate (Years 7–8) and Composite schools (New Entrant to Year 13), but not for Secondary schools (Years 9–13). Police vetting of all volunteers reducing EOTC had more agreement than disagreement only for Intermediate schools. Intermediate schools also most strongly agreed that difficulties getting caregiver/volunteer/parent support reduced EOTC. Adding police vetting of volunteers to a situation where schools were struggling to get enough volunteer help is likely to exacerbate this problem. Paperwork and workload reduces EOTC was an issue for all schools but had much higher agreement from Composite schools. Risk aversion impacted all schools similarly.

Outside of deciles nine and ten, schools agreed more that legislation meant they were doing less EOTC than they used to. School type was also an important factor with secondary schools showing less agreement that legislation reduced EOTC (32% agreement) compared to primary and intermediate schools (approx. 50% agreement). Notably, these responses compared existing and past provision of EOTC within each school and do not provide a means to compare the quantity of EOTC provided between different schools. While many schools are experiencing a reduction and threats to the quantity of EOTC, many other schools are soldiering on regardless, with no reductions in their programmes. In order to further understand these findings we turn to the qualitative data.

Qualitative analysis

To begin, we provide two responses which highlight both the pressures on EOTC and the four spheres of responsibility. One school continues to support EOTC while in the other, EOTC appears to be in decline. Both identify the tensions:

We have not reduced the amount of EOTC we participate in … The principal and teachers do … have increased worries about health and safety legislation and what this might mean for personal liabilities … which is not well understood by the BOT and community … Staff feel a need to fight the wave of over the top Health and Safety limitations because it impacts negatively on student learning; we feel the weight of legislation hanging over our heads.

The ability for schools to be secure in the knowledge that they can manage EOTC without endangering their staff, students or caregivers. … being confident that if a disaster occurs, the school’s safety action plans and risk management will be deemed to have been adequate to protect them from liability and accusations of negligence from their community, whānau and Ministry. This is a huge responsibility and definitely inhibits EOTC activities.

The first comment from a primary school respondent highlights how the worry and stress about personal liability impacts negatively on student learning. The second quote from a secondary school educator recognises the inhibitory nature of the safety challenges but acknowledges the importance of being confident in the planning processes to mitigate risks and protect all involved.

The sphere of responsibility for student learning and safety

The data supporting first order responsibilities to student learning and safety demonstrated 96% agreement that EOTC was valued and, as already signalled, that EOTC enhanced learning through ‘curriculum enrichment, student engagement, building personal and social skills and connections, and a sense of something new’ (Hill et al., Citation2020, p. 8). First order responsibilities to students’ safety and the care of other people’s children weigh heavily on the minds of many respondents:

Yeah, so I mean … of course there is an element of risk, so … you know, so the unexpected accident is the thing that probably is the scary thing for me. And that would be what worries me – when I am driving other people’s babies. That’s the thing that makes me lose sleep before I’m doing it and it makes me feel relieved when I get back.

This responsibility manifests as anxiety when the groups are away and the corresponding relief on their safe return. The departure to an EOTC event is preceded by a period of preparation where ‘All staff think long and hard about the responsibility they are prepared to take on’ (SS110, NEOTCQ). This level of reflection and planning is considered important for keeping students safe. Students also noted the changes in some teachers’ behaviour during EOTC, commenting that ‘I think outside they’re more strict … ’ (IS student FG) in order to manage student behaviour in public and also keep the students safe. Furthermore, the safety and acceptance of other community members is also given thought in planning, as an educator in a school for disabled students attests:

… to ensure their [students] safety, the safety of others and to enable them to participate as much as possible in the community. We select carefully the community venues re: safe access, community acceptance and ability to participate in community settings/programmes

Throughout the data there is evidence of a commitment to student learning and safety which always carried heightened awareness but now has increased anxiety and worry for staff. We now turn to another sphere of responsibility.

The sphere of responsibility to legislation

As discussed in the introduction the HSAWA and the CA were brought in with the express purpose of keeping people safe and preventing harm. Many participants indicated that fear of legislation was not a major barrier to EOTC and that educators and school leaders are very aware of the law and their responsibilities. For schools which have robust procedures the legislation is not problematic. As one respondent confirmed ‘You know you have got your systems in place and you know that they are set up … it is not as big a deal’(Staff Focus Group)

Conversely, we now reveal some of the work that the legislation does from the perspectives of those negatively affected, beginning with the threat of punishment. The data set contained many responses which focused on the potential liability faced, with typical responses including:

… the legislation, the threat hangs there, they know there’s that $600,000 that the headmaster could be [fined] … but we’re not going to let that get in the way

Yeah, we will be in jail … It is a threat because I mean, all of this stuff is because of legislation

Concerns about the threat of prosecution, fines and jail terms ‘hanging’ over people’s heads’ were common in the survey comments and interviews. Examples include a sense of being ‘thrown under the bus’ (Staff Focus Group) or suggesting that as a teacher ‘you are going to skate for it’ (Staff Focus Group), meaning an individual will wear the consequences. The worry many respondents express is not directed at whether they can keep students safe, but rather whether they will be punished; ‘that’s the thing that kind of freaks teachers out’ (Staff Focus Group). Some comments hold a sense of feeling unfairly targeted:

And of course, Health and Safety. When that came out and you know, the threat of fines and all these things … Sort of almost like threats being laid and I was like, …We don’t do this for the fun we do it for the kids. You know we are doing the best we can. And we … have put some things in place to make sure we … come through on those [HSAW responsibilities] but the standard teacher tends to shrink from those things. [personal liability]

Providing EOTC opportunities means going above and beyond educators’ usual workload to plan, prepare and run an out of school curriculum. Rather than being affirmed for this extra work and commitment, there is a feeling behind these comments that the legislation is treating them as potential lawbreakers who require threats of punishment for them to behave properly.

In the context of supporting the ability of teachers to use their judgement, one participant stated, ‘we need respect for common sense’ (SS Staff Focus Group). These comments point to an erosion of the view of teachers as trusted professionals. The upshot of these anxieties is that EOTC is no longer viewed as worth the risk and stress:

The fear of being sued if something goes wrong. People are scared to take trips because of the perceived risks [of legal liability]. (PS250, NEOTCQ)

[There is an] increased risk to Boards & Senior Leaders who sign off trips/activities.

Although in our school, we keep the focus on having EOTC trips and events, I know of local schools where H&S especially has severely interrupted their willingness to take camps and do trips.

Interviewees also raised another problem area concerning the adequacy of teacher training in preparing new teachers for the legal realities of the workplace:

There’s twenty hours in a four-year Bachelor of Education Degree for outdoor education and I mean you cannot tell me you learn everything in twenty hours.

If I was a young staff member entering now … this is just too hard, some of it just sits in the too hard basket.

This series of quotes indicates the concerns that legislation is discouraging a wide range of educators including senior leaders, BOTs and competent staff. Many respondents anxiously viewed the threats of legislation, specifically the HSAWA. Some felt a sense of injustice that they were being targeted and how this was dissuading a range of educators from running EOTC. Furthermore, indications are that the state of initial teacher education in EOTC appears parlous.

Overall, the impact of legislation is felt differently across schools depending on their locations, types (secondary, primary etc.) and deciles. Some school seem heavily impacted while others are able to maintain their programmes, regardless of the pressure.

Children’s act

Mirroring the quantitative data, there was not a large focus on the CA in the qualitative data but it is worth noting three aspects: prompting thinking and stress; adding workload; and creating anxiety for men:

You know things like the Vulnerable Children’s Act has totally changed the way that I think about planning trips and the stress that causes is quite big. So every time I am planning a trip I think right am I going to be placing the girls in to a vulnerable situation. If someone talks to them at the other end of the pool and they take offence to that have I allowed them in to this vulnerable situation? So there’s that kind of a whole element of it where once upon a time you could just take them, but because of the Vulnerable Children’s Act, thinking of that

For this educator, the CA has ‘totally changed’ their approach to planning and conducting swimming pool visits, and they now pay far greater attention to areas of heightened risk such as changing rooms, toilets, and interactions with other people at the pools. In this case, legislation appears to stimulate thinking. For some respondents, there is a difference between legislation directing peoples’ attention towards planning and the overall anxiety educators’ experience:

All of the above [barriers] are true. It’s just meant more work. We haven’t done less trips. We are in fear of not getting enough police-vetted parents for one of our trips. Also non-compliance with the Vulnerable Children’s Act [means] … children would miss out.

The time required for processing CA police check paperwork of up to five weeks means that the checks must be completed several weeks beforehand. The respondent above noted the possibility of running the EOTC event before vetting is completed (ironically to ensure safe ratios) and this would put them outside accepted practice. The quantitative data also suggests that primary and intermediate schools are most in agreement that the vetting of billets and volunteers reduces the amount of EOTC. It is possible that this arises because these schools rely most on parent or volunteer help in EOTC. In addition to the logistics of completing police vetting on time, a small number of participants noted that the CA affected men more strongly, particularly in primary schools where men historically have felt the most in danger of accusations of inappropriate behaviour. As one primary school respondent suggested, ‘People are fearful, especially men taking girls on camps and activities’. (PS310, NEOTCQ).

Many respondents felt that EOTC was being reduced by the threat of legislation. The fear and anxiety is palpable:

As a school leader the liability and risk is very real to me. Try not to over think it but I feel fear and anxiety when a group is away. We reduce risks but the blame and litigious climate is real in our community/society.

Both the quantitative and the quantitative data showed that many respondents agreed that the threat of legal liability looms large in the minds of school staff and is a source of anxiety, fear, and also a sense of no longer being trusted. In some schools this is leading to a reduction in the quantity of EOTC. In others, the staff feel the anxiety but continue to provide EOTC as much as before the legislative changes:

In practice and reality we are doing the same old same old, but there is a concern that if that thing does go wrong or that your process aren’t robust enough … that is a concern I guess in the back of the mind.

I think in practice nothing … has really changed. (Staff Focus Group).

We were always aware of the EOTC requirements. The changes that have been made have allowed us to develop more skills and tighten procedures.

Additionally, educators who access professional development feel more prepared and less anxious or fearful:

One of the best things I’ve ever done was a course … that was funded by the Ministry. It was fantastic … We had great facilitators who knew what they were doing … they made everybody in the room feel the same way. In terms of EOTC it was well explained … the kinds of ways that it could enhance the curriculum, but also taking away the scariness of it, and I think if every teacher was given that opportunity, how much better it would be.

Discussion

This research investigates the influence that legislation has on EOTC in NZ from the perspectives of educators and school leaders. Findings reveal a divergence in the influence of legislation, with 44% of educators and school leaders recording a reduction in EOTC and 35% reporting no change. The application of legislation to EOTC appears to be causing anxiety for both groups.

The most important sphere of responsibility is to ensure quality and safe learning experiences for students. Powerful learning opportunities are provided through EOTC to achieve optimal student engagement and learning (Hill et al., Citation2020). Yet many teachers and school leaders experience increased anxiety in the safety process, which has also been reported in prior research (see Sullivan, Citation2014). Teacher anxiety levels have increased with the movement of safety management to a systems approach with compliance to legislation part of the accountability ideology of neoliberalism (Hollingsworth, Citation2011, cited in Brookes, Citation2018, p. 204; Sullivan, Citation2014). The present research emphasises that organisations and educators take safety seriously at both the compliance and operational levels.

Looking at the sphere of responsibility relevant to the legislation, we found that more schools agreed or strongly agreed that the HSAWA legislation reduced EOTC in their school (44.4%) compared to those schools that disagreed or strongly disagreed (34.7%). A curious finding showed that schools ranked decile 9 or 10 reported a higher level of disagreement than agreement that HSAWA legislation reduced EOTC and contrasted with schools from deciles 8 and below. High decile schools (9 & 10) draw students from more social and economically advantaged areas. In comparison, it should be noted here that deciles 1–8 represent a very wide range of schools and communities with increased diversity of students, far from a homogenous group. It is therefore difficult for us to comment on why this difference exists between the highest two decile schools and the rest.

The nature of EOTC, especially the school camp, is often a stressful event that requires working excessive hours with unpaid night work. Factors such as fatigue, negative sleep effects and domestic disruption increase the risk factors and the likelihood of mistakes being made (Bohle et al., Citation2008; Brookes, Citation2018). For some staff, the knowledge of the extra work involved in EOTC resulted in feelings of being unfairly treated as potential criminals, rather than as committed professionals. Murphy (Citation2022) found that when the law entered educational contexts overtly, educators lost confidence in themselves, their ability to make judgements and also their confidence in the system. This can lead to ‘an emphasis on avoiding liability, rather than ensuring responsible decision-making through experience-based judgement’ (Hollingsworth, Citation2015, p. 106). We now turn to two interpretations of this situation, both of which have the potential to stymie EOTC: competent teachers who become overly anxious; and lack of knowledge and training to feel confident.

Anxiety caused by the direct concerns for student safety, combined with fear of the law can poison the goodwill required for EOTC. The findings refer many times to being scared of being found legally liable. For educators whose primary focus becomes avoiding legal liability, this fear may suggest a separation of the expectations of the law and the expectations of teaching students and keeping them safe (Hollingsworth, Citation2015, p. 109). Safety management may then become conceptualised as being something added to or another burden rather than inextricably underpinning planning and implementation. As with this study, Murphy (Citation2022) found that fear of the law meant some teachers were likely to stop taking children out of the classroom.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the devolution of responsibility to school BOTs and principals means they are ultimately responsible for student safety and feel most exposed to risks of legal action. Interestingly, risk aversion was not seen as a significant barrier by 40% of the respondents. The 35% who agreed were represented by the quotes which expressed fears of prison sentences and hefty fines.

A second potential interpretation of staff anxiety is when the law highlights the importance of student safety to teachers who do not feel competent in taking students outdoors. Brookes (Citation2018) strongly believes that the key to safety is competent, experienced staff, well supported with professional development. North (Citation2020) also emphasises that outdoor education requires deep understanding of our students and our environments. In the situation where staff do not feel confident or competent, the threat of legal punishment may do productive work in keeping students safe by programmes being amended or withdrawn. Contracting EOTC out to skilled and qualified providers is one possible solution but comes at a financial cost. Another option is to offer low-risk alternatives and use familiar environments that do not require higher competence levels (Brown & Fraser, Citation2009).

As identified in these findings and also in the wider report (Hill et al., Citation2020), the time and curriculum available in initial teacher education (ITE) for EOTC has been drastically reduced. Consequently, there was ‘ … concern that beginning teachers were not well equipped to lead EOTC … ’ from their initial teacher education programmes (Watson et al., Citation2020, p. 28). In addition, existing staff with extensive EOTC experience are aging and retiring. In the past, new graduates entering schools have been able to rely on support from established EOTC ‘Champions’ (Hill et al., Citation2020) and in their absence, EOTC is in danger of falling into what could be termed a demographic bottleneck.

The evidence suggests that EOTC continues to be part of the fabric of schooling in Aotearoa New Zealand (Hill et al., Citation2020) and the situation where EOTC is no longer offered would represent a major loss. The findings support that there are challenges to the provision of EOTC as a pedagogical experience. There are ‘mitigations’ available to ameliorate this situation (see for example Watson et al., Citation2020) and we now turn to these.

For EOTC in schools to be responsive to, and resilient within an everchanging educational environment in Aotearoa New Zealand, four interconnected enablers have been identified (Hill et al., Citation2020). The first enabler broadly addresses the importance of the context for EOTC provision by honing in on a supportive school culture and community. Secondly, EOTC champions who may be individuals such as EOTC coordinators or small groups within or sometimes external to the school, can be a significant stimulus to EOTC. In concert, we suggest these first two enablers may provide important ‘buffering’ effects to the concerns, stress and workload many schools reported, and provide greater certainty in meeting legal requirements in EOTC.

The third and final enablers focus on EOTC systems and professional learning and development (Hill et al., Citation2020), both of which are directly implicated in the findings reported on here. For example, a small number of respondents proposed a positive influence of legislation on a school’s safety focus, suggesting a good alignment between the intentions of the legislation and practices in these contexts. Good systems, including the people who contribute to them, are integral to supporting a view of EOTC as a school-wide contribution and not simply a solo endeavour. The enabler of in-service professional learning opportunities can also be vital for developing teacher capability and confidence and strengthening safety management practices and systems (Hill et al., Citation2020). In-service learning can be provided in a variety of ways often facilitated by national subject associations such as in Denmark (Bølling et al., Citation2024). Within Aotearoa New Zealand, opportunities funded by the Ministry of Education and taught by members of the subject association (Education Outdoors New Zealand) show considerable promise and are lauded by many respondents in this study. These include two day ‘EOTC and effective safety management systems’ and a one day ‘embedding good practice systems for EOTC’ course. School staff indicated that attending these courses help reduce anxiety and build confidence through developing understanding of the expectations around student learning and safety. Unfortunately, the survey also indicated a number of school leaders who were unaware of the training or in remote locations and struggled to attend. Teacher shortages and workload is another variable that impacts attendance at such in-service training opportunities.

Conclusion

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the HSAWA was intended to ensure that people came home safely and the CA sought to safeguard children. In this paper, we suggest that the intersection between law and society is complex.

The CA and associated police vetting of volunteers impacts intermediate and primary schools provision of EOTC most strongly. These levels of schooling typically rely on parents more and the intermediates are generally located in urban areas where parents are often committed elsewhere. In addition, the CA appears to have an impact on male teachers. This tentative finding aligns with the literature, suggesting that the CA has influenced male physical education teachers and pushed them into what they term ‘defensive pedagogies’ in order to keep themselves safe (Bennett et al., Citation2022). This is an area ripe for further research.

In terms of the HSAWA, the weight of the responsibility for student learning and safety came through strongly from educators and school leaders. Nevertheless, there have been fatalities in EOTC over the years. Brookes’ (2018) finding that most of these fatalities could have been avoided, re-emphasises the ongoing imperative for positive and pro-active approaches to health and safety. Early in this article we noted Selznick’s (Citation1996) query about what processes frustrate or give hope to safety legislation and this remains pertinent. By examining the work done by the legislation in EOTC more broadly (not just a focus on processes), there are several important observations to make.

When legislation enters the EOTC context we see two distinct groups emerge. The first was those for whom the legislation reduced their willingness to support EOTC because of the perceived risk of legal liability. The second group were those who felt fewer anxieties about the legislation and therefore did not reduce provision. Looking deeper, school types were impacted differentially. In particular, schools in the most affluent category experience less anxiety and less pressure. For educators who are less experienced and confident in planning and conducting EOTC, the legislation sharpens the mind towards reducing provision and/or finding lower risk alternatives. Lower competence levels of new staff arise from the absence or deficit of EOTC curriculum in ITE programmes which raises critical questions about the future of EOTC.

While our findings do not indicate whether the HSAWA is making students safer, the legislation clearly has consequences for EOTC. In almost half the schools, findings show the HSAWA and paperwork are perceived as reducing the provision of EOTC relative to what each school was previously offering. Even small reductions in EOTC are a loss to student learning (Hill et al., Citation2020). By these measures, how the law is being perceived and put to work is impacting on students’ access to the rich and diverse educational experiences of EOTC.

The partner paper (Part 2) (North et al., Citation2024) will continue this analysis of the work that the law does in EOTC and examine the responsibilities to compliance through paperwork.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive engagement with our work which considerably strengthened the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chris North

Chris North is an Associate Professor in Te Kaupeka Oranga Faculty of Health at the University of Canterbury. Chris’ research is in the areas of outdoor education and recreation practices, environmental education and initial teacher education. He uses mainly qualitative methodologies to closely examine experiences in outdoor and out of school contexts.

Marg Cosgriff

Marg Cosgriff is a senior lecturer in Te Huataki Waiora School of Health at the University of Waikato. Marg’s research interests include outdoor learning, youth wellbeing, human-beach relations, and visual and mobile methods.

Mike Boyes

Mike Boyes is an Associate Professor in Outdoor Education at the University of Otago. His extensive influence on theory and practice in outdoor education and recreation is recognised through the Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit (2009) and the Sir Eion and Jan, Lady Edgar Lifetime Achievement Award from Sport New Zealand (2022).

David Irwin

David Irwin PhD is the programme manager of Sustainability and Outdoor Education at Ara Institute of Canterbury. His research and teaching interests lie in the exploration of culture, identity and human nature relationships, education for sustainability and social change in an organisational context.

Allen Hill is Kaiwhakahare Te Hoe Aronui | Head of the Humanities Department at Ara Institute of Canterbury. Allen has been a lead contributor to the EOTC in Aotearoa New Zealand research group over the last five years. His main research interests focus on how education can engage people with meaningful outdoor learning experiences and contribute to a sustainable future through connecting people with each other and with the places they inhabit.

Sophie Watson

Sophie Watson has held numerous roles in the education sector, including as a secondary school teacher and educational researcher. Following her Master’s research, she was inspired to develop ‘Going with the flow’ – a multi-media resource that supports schools and outdoor centres to embed gender-inclusive practices in outdoor experiences. Sophie currently works as a professional learning facilitator and resource developer for Education Outdoors New Zealand.

Notes

1. Aotearoa New Zealand is a style convention of the NZ Government out of respect for the indigenous Māori people and the bi-cultural and bi-lingual context of this country.

References

- Barfod, K. S., & Bølling, M. (2022). Anticipated bias in education outside the classroom research – do we promote representative participation? 9th International Outdoor Education Research Conference (IOERC), University of Cumbria, Amberside https://ioerc9.org/

- Bennett, B., Fyall, G., & Hapeta, J. (2022). The sword of damocles: Autoethnographic considerations of child safeguarding policy in aotearoa New Zealand. Sport, Education and Society, 27(4), 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1877125

- Bohle, P., Buchanan, J., Cooke, T., Considine, G., Jakubauskas, M., Quinlan, M., Rafferty, M., & Ryan, R. (2008). The evolving work environment in New Zealand: Implications for occupational health and safety. National Occupational Health and Safety Advisory Committee (NOHSAC).

- Bølling, M., Elsborg, P., Stage, A., Stahlhut, M., Mygind, L., Melby, P. S., Barfod, K. S., Amholt, T. T., Fernando, N., Ventura, A., Mikkelsen, S., Müllertz, A. L. O., Otte, C. R., Brønd, J. C., Klinker, C. D., Aadahl, M., Nielsen, G., & Bentsen, P. (2024). Exploring the Interplay of Three Danish Research Initiatives on Education Outside the Classroom: Findings and Future Directions. 10th International Outdoor Education Research Conference, Japan.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brookes, A. (2018). Preventing fatal incidents in school and youth group camps and excursions: Understanding the unthinkable. Springer.

- Brown, M., & Fraser, D. (2009). Re-evaluating risk and exploring educational alternatives. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 9(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670902789529

- Children’s Act. (2014). Retrieved March 3, 2023, from https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2014/0040/57.0/DLM5501618.html

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Goodson, I. (2000). The principled professional. Prospects, XXX(2), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02754064

- Gunningham, N. (1999). Integrating management systems and occupational health and safety regulation. Journal of Law and Society, 26(2), 192–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6478.00122

- Haddock, C. (2007a). Education outside the classroom (EOTC) survey: Primary school report. Ministry of Education.

- Haddock, C. (2007b). Education outside the classroom (EOTC) survey: Secondary school report. Ministry of Education.

- Health and Safety at Work Act. (2015). Retrieved February 15, 2015, from https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2015/0070/latest/DLM5976660.html8608

- Hill, A., North, C., Cosgriff, M., Irwin, D., Boyes, M., & Watson, S. (2020). Education outside the classroom in aotearoa New Zealand – a comprehensive national study. Ara Institute of Canterbury Ltd. https://www.eonz.org.nz/assets/Resources/Research/EOTC-in-Aotearoa-New-Zealand-Final-Report-2020-compressed.pdf

- Hollingsworth, R. (2015). A tale of two tragedies: Identifying changes in outdoor education ‘best practice’. New Zealand Journal of teachers’ Work, 12(2), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.24135/teacherswork.v12i2.176

- Mannion, G., Mattu, L., & Wilson, M. (2015). Teaching, learning and play in the outdoors: A survey of school and pre‐school provision in Scotland. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report.

- Ministry of Education. (n.d.). Ministry funding deciles. https://parents.education.govt.nz/secondary-school/secondary-schooling-in-nz/deciles/

- Ministry of Education. (2016). EOTC guidelines 2016: Bringing the curriculum alive. Learning Media Ltd.

- Murphy, M. (2022). Taking education to account? The limits of law in institutional and professional practice. Journal of Education Policy, 37(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1770337

- North, C. (2020). Interrogating authenticity in outdoor education teacher education: Applications in practice (Vol. 21). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2176-8

- North, C., Boyes, M., Irwin, D., Cosgriff, M., Hill, A., & Watson, S. (2024). The work that the law does in education outside the classroom: Part 2, the paperwork dilemma. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2024.2372391

- North, C., Hill, A., Cosgriff, M., Watson, S., Irwin, D., & Boyes, M. (2022). Conceptualisations and implications of ‘newness’ in education outside the classroom. Cambridge Journal of Education, 53(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2022.2094893

- Selznick, P. (1996). Institutionalism “old” and “new. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(2), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393719

- Suchman, M. C., & Edelman, L. B. (1996). Legal rational myths: The new institutionalism and the law and society tradition. Law & Social Inquiry, 21(4), 903–942. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.1996.tb00100.x

- Sullivan, R. (2014). A review of New Zealand’s EOTC policy and curriculum: Changing meanings about safety. Curriculum Matters, 10, 73–93. https://doi.org/10.18296/cm.0176

- Watson, S., Hill, A., North, C., Irwin, D., Cosgriff, M., & Boyes, D. M. (2020). Flourishing EOTC in aotearoa New Zealand: Challenges and solutions. SET, (2), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0168