ABSTRACT

In Part 2 we examine how compliance with Health and Safety at Work legislation through paperwork impacts EOTC. The literature suggests writing promotes thinking, particularly when viewed as a process and not just a product. Results from a national survey and interviews show that paperwork is a major barrier to EOTC for many schools. Analysis identified three approaches to mitigating the burden of paperwork: halting EOTC; performative and ritualistic approaches to paperwork; and creating systems which streamline paperwork to maximise its relevance. Halting EOTC effectively eliminates an approach which benefits a wide range of students. Taking a performative approach to paperwork allows teachers to avoid what they see as meaningless work, but short-cuts important opportunities for reflection and potentially causes non-compliance with the law. Possible solutions which allow EOTC to continue to flourish involve creating and resourcing effective systems staffed by dedicated EOTC coordinators and competent staff.

Introduction

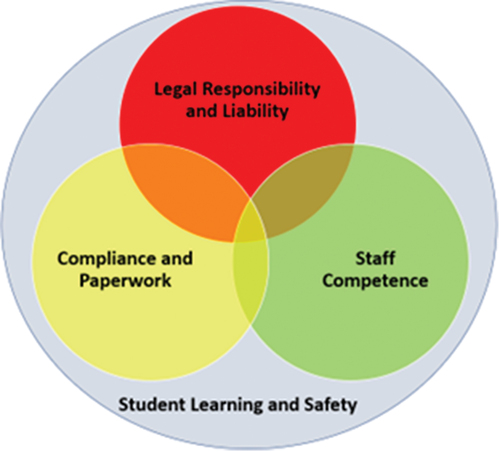

In this article we extend on ‘The work that the law does in Education Outside the Classroom: Part 1, The law and student safety’ (North et al., Citation2024) to examine the connections between paperwork, student safety, and EOTC provision in schools in Aotearoa New Zealand.Footnote1 Anecdotal accounts from teachers and principals indicated that paperwork was negatively impacting the provision of EOTC in schools. Here we examine the upshot of legislation with a particular focus on the paperwork used for planning of EOTC. As depicted in our spheres of responsibility framework (see ), the ultimate responsibility of educators and school leaders is to student learning and safety, underpinned by legal responsibilities, competent staff and supported by systems which include paperwork and demonstrate compliance. We acknowledge that these spheres of responsibility are mutually supportive, can have considerable overlap, and the delineations are blurred. However, conceptualising different responsibilities to a safety system allows for a conversation about the interplay between the responsibilities within that system.

Following the words used by participants in this study, we use the term ‘paperwork’ to describe the documentation (often completed electronically) in preparation for EOTC. Paperwork involves writing, which can be used to promote thinking but there are some important caveats which we unpack through the broader context of education and of outdoor learning in particular.

We begin by briefly revisiting legislative and social connections relating to health and safety before exploring the contested relationship between writing and thinking, looking at paperwork in education more generally and paperwork in EOTC and outdoor learning specifically.

Legislation, society, and paperwork

In Part 1, we explored the complex interaction of law and society and how legislative requirements impact EOTC practice. While the intentions of the legislation may appear simple; for example, that people should come home from work or school safe and healthy, the enactment of such statements is complex and socially mediated. Worksafe (Citation2017) the NZ Government safety body, sees documentation as integral to an organisation’s safety culture. By statute, they mandate health and safety documents to: ‘ … monitor progress, changes, adherence to agreed ways of working, and compliance.’ Gunningham (Citation1999) and Bluff and Gunningham (Citation2012) argued that the law in relation to Health and Safety at Work (HSAWA) can stimulate modes of reflection and is effective because it forces educational organisations to improve their procedures and systems. However, Suchman and Edelman (Citation1996) highlighted the potential for compliance with the law to become symbolic, performative and ritualistic rather than thought-provoking. Symbolic or ritualistic behaviours may arise through the process of compliance, and these behaviours shape organisational and individual actions which ultimately determine whether a law will achieve its goals. Compliance and associated behaviours take on distinct forms in different social contexts and often result in the production of paperwork.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the process of neoliberalism has devolved authority to school principals and boards of trustees (BOT), and accountability has become a key means of controlling and measuring education (Court & O’Neill, Citation2011). In England, there is a similar neoliberal trend. Murphy (Citation2022, p. 6) notes that:

The paper trail is an (unwitting) focal point for law and accountability to reinforce one another, precisely because the transparency demands of accountability require the gathering of a substantial evidence base. This evidence base can simultaneously satisfy accountability protocols while also … [acting] as a prized source of legal evidence.

Here Murphy suggests that paperwork serves as both accountability for the neoliberal system of measurement, and as evidence for the law should compliance be tested. These conflated uses of paperwork make for divergent purposes; whereby accountability becomes framed as risk management (Brown & Calnan, Citation2009). For example, and in the context of EOTC, the paperwork developed by the teacher will be used to gain permission from the principal for the trip, which is justified by learning outcomes, managing student safety, costs and perhaps also alignment with school purpose and values. Should a significant incident occur on an EOTC trip, this same paperwork will serve as evidence in a court of law where the prosecution is seeking to find an absence of a duty of care. These differing purposes of paperwork make the completion of paperwork by teachers potentially fraught.

Paperwork as a legal liability

There is a paradox in the assumption that paperwork can help mitigate legal liability. Where paperwork is an accurate reflection of practice, paperwork provides evidence of diligence. However, when there is poor alignment between what is documented and what actually happens, lawyer Greg Smith maintains there are grounds for prosecution (Human Dimensions, Citation2023). If paperwork describes practices, and there is noncompliance with those practices, ‘you will be held liable, and the paperwork used as evidence against you.’ Further adding to the legal liability, particularly for those overseeing systems, is when a database of paperwork that is amassed over time demonstrates noncompliance. In cases such as these, paperwork becomes a legal liability.

In addition, overly complex paperwork systems can function to disguise noncompliance for those who are legally responsible such as principals and school boards of trustees. As Smith suggests, this is because ‘the more complex your systems are, the less you are likely to know about whether they are actually happening in practice’ (Human Dimensions, Citation2023). Further, the more complex a system becomes and the more onerous it is to complete, the more disconnected the workforce becomes. It is logical that when expectations of paperwork are overly complex and detailed, it becomes increasingly difficult to achieve compliance in practice. Thus, complexity of paperwork again increases legal liability.

In summary, the effectiveness of laws in achieving their intended objectives becomes either supported or undermined by a welter of social processes. The actions involved in demonstrating compliance may result in proactive reflection which reduces incidents of harm or disconnected symbolic rituals. As much of the evidence of compliance with the HSAWA legislation involves paperwork or documentation, it is important to review the connection between writing and thinking.

Writing as thinking

Evidence of legal compliance is often demonstrated through written documents. This premises that writing equates to thinking (Gunningham, Citation1999), and that paperwork is the best way to provide evidence of compliance. In this section we draw on the work of authors who examine the connection between writing and learning. It is also plausible that teachers and school leaders’ beliefs about writing are socially constructed through a long period of involvement in education. From a historic perspective, White (Citation1993, p. 107) suggests:

The academic traditions of writing: essay exams, term papers, senior and post-graduate theses, books and articles, and so on, which for hundreds of years have led to and demonstrated learning and individualized thinking. Academic traditions and current practice confirm the central importance of writing for learning and demonstrating critical thinking and problem solving.

In many ways, engaging in critical thinking and problem solving through a writing process is a learning and planning process. Studies of the cognitive process where writing and learning are entwined highlight the neural activity in the brain that is linked to memory retention and the coding of new information (Arnold et al., Citation2017; Haridy, Citation2020). Learning through the writing process occurs when content is constituted in the act of writing. In summary, Galbraith and Baaijen (Citation2018) believe the construction of text is an active process of firstly, knowledge-constitution through which understanding is realised and secondly, knowledge-transformation where ideas are reworked to satisfy legislative and learning contexts.

As well as a learning process, writing is a planning process to clarify goals, consider timeframes, maintain stability, reduce oversights, and identify problem areas (Boyes et al., Citation2018, p. 2). The work involved in thinking through an activity produces a malleable roadmap of procedures and provides a framework to enhance a teacher’s ability to adapt to eventualities (ibid). Planning is a combination of both mental and physical work as the safety management plans and teaching lesson plans are written concurrently with the physical preparation of the activity and teaching resources. In practice, the two are inseparable. Furthermore, written plans are vehicles for learning in hindsight and re-planning for future events.

There is also a difference in learning effect from thought processes where deep processing of the material is enacted through writing (Arnold et al., Citation2017; McLeod, Citation2007). Rather than a superficial scan, deep processing needs more time to thoroughly think something through, leading to a more meaningful analysis and better recall. The cognition greatly considers context and relevance to the task at hand. Deep processing is slower, more effortful, controlled, conscious, and demanding of working memory (Evans, Citation2008). Writing outputs provide an external record of the path of our thought and enhance the possibilities of sharing, discussion, and reflection (Galbraith & Baaijen, Citation2018). Through this process, the whole plan is tangible and committed to long term memory, available for implementation on demand.

Hayes and Nash (Citation1996) also make another important point very relevant to overworked teachers. They recognise the writing process mostly takes place within the human mind which is a limited capacity system. Hence the fundamental source of conflict in writing is characterised as cognitive overload, which impairs the process and quality of decisions (Jingshan et al., Citation2019). Consequently, balancing planning requirements and teacher workload under time pressure can lead to shortcuts, superficiality and under performance.

It is important to recognise that in contemporary society the very nature of writing has changed. Smith (Human Dimensions, Citation2023) notes that complex, digitised paperwork systems for use on mobile devices are likely to speed up the completion of paperwork and may result in superficial involvement in thinking. Technology can make us less critical and less engaged in the process of effective planning. As Leijten et al. (Citation2014, p. 285) identify: ‘In today’s workplaces professional communication often involves constructing documents from multiple digital sources.’ In contemporary society, the process of developing documents may include artificial intelligence input, which poses a different set of challenges regarding contextual relevance. While the desired safety and learning goals of safety plans remain the same, the process by which they are achieved has morphed. Scavenged material is merged with an individual’s ideas. In a digital workplace: ‘Document reuse and adaptation now pervade the practice of professional communication’ (Swarts, Citation2010, in; Leijten et al., Citation2014, p. 286). Cut and paste prevails. What does this mean for our safety thinking processes?

Where writing is used to demonstrate thinking, a dual purpose can be identified; writing as a process and as a product. Early on, White (Citation1993) argued that the writing process stimulates thinking and this exceeds the value of the document produced. Undoubtedly, a writing process helps with reflection, organising thoughts, distilling information, critical thinking, clarity, enhancing memory and goal clarification (Goldberg, Citation2005; Lamott, Citation2020). It forces an individual or group to structure, reflect and refine thoughts and is very much an effortful, ‘thinking slow’ attribute (see Kahneman, Citation2011, System 2). By contrast, writing defined only as a product requires a focus on what White calls ‘correctness’ which counts far more highly than originality, or a well-developed idea. White maintains that ‘For higher-order thinking skills, we must focus upon writing as a process, and writing as an active, individualising skill intimately related to critical thinking and problem solving’ (White, Citation1993, p. 111). Research concludes that writing to generate a product stimulates less thinking than writing to emphasise a process (see Arnold et al. (Citation2017); McLeod (Citation2007); White (Citation1993)).

This literature is relevant for using written products for compliance because it is the cultural context which constructs the symbols of compliance and ultimately determines if the law is to be effective. For example, and from a very different discipline of nursing in the United States, Ferrell (Citation2007, p. 61) states that ‘documentation of care is synonymous with care itself.’ Ferrell notes that when a jury is assessing a case in court, the only evidence of care is the documentation that was written, sometimes many years, earlier. The context of education is far removed from medicine, yet there are some parallels. Namely, that written products can be used in a court to evaluate whether an individual or organisation complied with a law (Ministry of Education, Citation2016). We return to the notion of paperwork as a legal liability later in this section.

Paperwork in education

Here we look briefly at some examples from education more broadly and show how the role of paperwork has grown and how educators perceive this paperwork. In a study by Fitzgerald et al. (Citation2019) into the impact of devolution on the work of teachers, a participant commented that they had ‘always felt swamped by the paperwork’ (p.623). Fitzgerald noted the frequency of references to paperwork by interviewees was striking. In addition, the results of a survey of teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand, show that teachers see much of the paperwork as providing no benefit to teaching and learning but rather view it as a distraction (Wastney, Citation2018). This disconnection between paperwork and student learning is echoed in research from Sweden where teachers felt that an ‘Individual Education Plan’ for a student is reduced to the writing of the document and therefore it ends up as a procedural display rather than a series of actions (Hirsh, Citation2014). Wastney (ibid, p.7) agrees and finds that the paperwork was intended to help teachers improve their teaching but: ‘A lot of it seems to be paperwork as proof of having done other paperwork. It comes down to a lack of general trust in teachers’ judgement as professionals.’ Karseth and Møller (Citation2020) also propose that while the decisions of teachers allow institutions to function, this power to make decisions rests on the trust that teachers can and do use their professional expertise. In England, Murphy (Citation2022, p. 6) suggests there is now a ‘perceived threat of unchecked professional ineptitude’ which has required increasing accountability and control, and which is largely enacted through paperwork.

The high workload of educators and school leaders is highlighting the quantity of paperwork; the amount of paperwork is making the teaching profession more clerical than pedagogical (Anderson & Terras, Citation2015; Wastney, Citation2018). In summary, the literature suggests that paperwork: has an adverse effect on student learning through taking teacher time and energy; is often seen as irrelevant; detracts from teachers’ primary motivations; and creates a feeling that educators are not trusted. Next, we look at whether this also applies to paperwork for outdoor learning.

Paperwork, safety and EOTC

Within EOTC contexts, paperwork fulfils a number of roles including enhancing students’ learning outcomes; strengthening safety management; gaining approval from Board of Trustees (BOT) (or delegate); and informing parents (Ministry of Education, Citation2016). The main resource to support EOTC, the ‘EOTC Guidelines’ (Ministry of Education, Citation2016), is careful to position learning before safety, and to advocate for keeping paperwork in proportion to the level of risk of the EOTC context. This was in part due to the responses of teachers to earlier resources which had led to EOTC becoming a ‘site of anxiety’ (Sullivan, Citation2006, p. 6) for teachers. At times expectations about paperwork cause conversations about EOTC to become dominated by discourses about risk and safety (Sullivan, Citation2014; Sullivan et al., Citation2011; Zink & Leberman, Citation2001). Does this focus on safety and risk lead to a greater commitment of teachers to paperwork?

The connection between paperwork and enhanced student safety in outdoor learning is not clear. This is due to several factors including the attitudes of teachers to paperwork. For example:

Rather than seeing formal risk management as keeping students safe and promoting thinking, people have approached it as ‘busy work,’ documenting what we have already been doing in their routine planning, teaching and instructing, and under the illusion that this has reduced the level of risk. (Hogan, Citation2002, p. 74)

If teachers view paperwork as a pointless ritual, their engagement with the process and the thinking that it should elicit will be severely curtailed. Threats of legal action or liability may provide some motivation for taking planning for safety more seriously. However, Brookes (Citation2018) notes there are significant limitations to this form of motivation because a culture based on fear of liability could discourage open discussions of safety. Brookes also acknowledges that by accepting responsibility for the care of others, teachers must also accept responsibility for failure to exercise that care. While not dismissing safety processes and in particular paperwork, Brookes (Citation2018, p. 206) is convinced that staff competence and experience is key because ‘safety remains ontologically bound to placing youth in the care of safe hands.’ The connections between paperwork, student safety and EOTC appear complex and highly reliant on the thinking that should be supported through the act of completing paperwork (see for example Dallat et al. (Citation2018)). It is also clear that the paperwork should not replace, but rather complement, the presence of an experienced educator on the EOTC trip.

Summary

Anecdotal accounts suggested that the HSAWA legislation was potentially reducing the provision of EOTC by schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. The literature shows the contested relationship between the intentions and enactment of legislation (such as HSAWA), largely because of the way in which individuals and organisations interpret and enact the law which at times may lead to performative rather than thoughtful engagement. Compliance with the law is often evidenced through paperwork, and we present different ways in which the act of writing prompts or potentially hinders thinking. Importantly, paperwork can constitute a legal liability and be used to demonstrate noncompliance and a lack of due diligence. The literature suggests that paperwork is becoming a greater proportion of the role of educators and some literature shows that teachers struggle to see the benefits of this work, and often view it as a distraction from student learning. Within EOTC, the relationship between safety and paperwork is not straightforward.

Methodology

This article explores the work that the law does in EOTC with a particular focus on the relationship between paperwork, compliance, and student safety. In doing so, it draws on data from a national study conducted in 2018 which investigated EOTC in schools across Aotearoa New Zealand through the perspectives of principals, EOTC coordinators, teachers, and students. It includes primary schools (PS), intermediate schools (IS), secondary schools (SS) and composite schools (CS). The study adopted a sequential transformative mixed methods approach which integrated an initial questionnaire with quantitative and qualitative questions (NEOTCQ) with subsequent qualitative interviews (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2017).

The quantitative data was gathered by an online Qualtrics questionnaire adapted from the work of Mannion et al. (Citation2015), with content validity established through feedback from an expert group including representatives of principals’ organisations and outdoor education academics. An invitation email was sent to all school contacts on the New Zealand Ministry of Education website and the response rate was 523 responses (21%) overall, made up of Principals (60%), EOTC coordinators (22%), and teachers and curriculum leaders (18%).

From a question on the questionnaire, 20 schools volunteered to participate in the follow-up interview phase, and these were visited in person, with two exceptions where interviews were conducted by Zoom due to remoteness and logistical constraints. Staff members and principals were interviewed individually, and student (aged 6 to 18) interviews were conducted in focus groups. Undoubtedly, the data reflects the views of people, schools and organisations with an interest in EOTC (Barfod & Bølling, Citation2022). Ethical approval was gained from the ARA Institute of Canterbury before commencement.

In the data analysis, descriptive statistics and relationships were initially produced from the quantitative data, before the qualitative data was explored thematically through a coding process to identify key themes or patterns from participants’ perspectives (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Integrated analyses of both quantitative and qualitative data were then conducted collaboratively to identify major trends and themes.

Findings: paperwork and compliance

Concerns about the effects of paperwork on EOTC came through very strongly in both the quantitative and qualitative data. To unpack some of the trends, we first present the quantitative data before turning to the qualitative data.

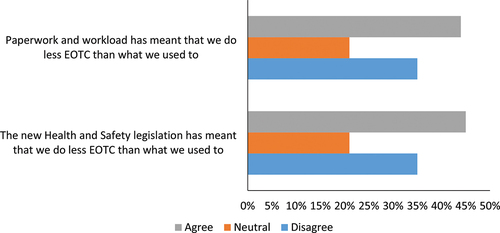

Quantitative data in , suggests that two factors in particular were seen as problematic by some school leaders/EOTC coordinators and not by others. The two factors that had more agreement as impacting negatively on EOTC quantity were:

Paperwork and workload − 44.2% agreement v 35% disagreement (mean = 3.16)

New health and safety legislation 44.4% agreement v 35% disagreement (mean = 3.19)

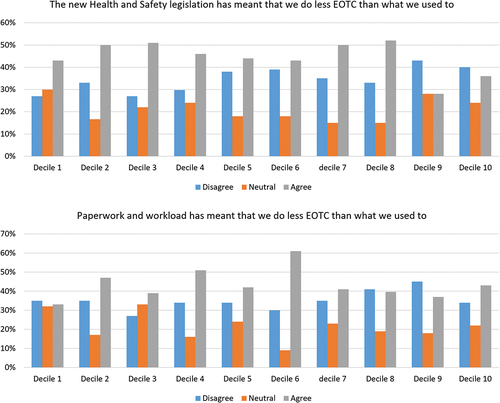

The results in show that decile 9 and 10 schools perceive Health and Safety legislation as a less significant barrier to EOTC quantity than schools from the other deciles. Decile is a funding mechanism that rates schools from 1 to 10 with 1 being communities with low socio-economic status and 10 being wealthier communities with high socio-economic status (see Ministry of Education, Citation2020). No clear pattern is discernible for ‘paperwork and workload’ because there is variability across the decile range. Had there been a similarity between the responses to HSAWA and to paperwork and workload, it might have suggested that the barriers to EOTC from HSAWA could be explained by the requirement for paperwork and impact on teacher workload. Because this relationship is distinct, there is something about paperwork that is worthy of separate analysis. We elaborate on this in the qualitative findings.

School type was also found to have an influence on the impact of paperwork and workload. It was an issue for all schools but had much higher agreement from Composite schools (years 1 to 13) (63%) as compared to Secondary (Years 9 to 13) (43%), Intermediate (Years 7 & 8) (44%) and Primary (Years 1 to 8) (42%) schools. Special schools (e.g. for learning disabilities, health impairment etc) had the lowest rates of agreement with this statement (20%) and disagreement was high (54%). Given that different school types can be contextually quite distinct, these results are not surprising. For example, composite schools are dealing with issues impacting all school age levels, often have smaller rolls and workload is distributed across fewer staff. Special schools tend to have higher community and parent engagement perhaps protecting them from some of the impact of these barriers. Overall, the data show that paperwork and workload are impacting most schools, some to the detriment of EOTC and others where EOTC is being maintained.

Qualitative analysis

Student learning and safety are at the heart of EOTC (Ministry of Education, Citation2016). The HSAWA legislation is intended to promote a focus on safety and in Part 1 (North et al., Citation2024) we explored the relationship between spheres of responsibilities to student safety, to the law and to staff competence. The findings from Part 1 clearly showed that perception of legislation engendered anxiety amongst many staff, including in schools where EOTC programmes were continuing. Being compliant with the law is one way to reduce fears of the law, and paperwork is typically how organisations and individuals demonstrate this compliance. It was therefore crucial to understand perceptions of paperwork.

The new Health and Safety legislation has meant we have needed to change the way we think about EOTC and has added lots of hours of work ‐ not always hours that are worthwhile! It has made us overly cautious. Paperwork is also demanding and repetitive. (PS303, NEOTCQ)

This quote suggests that the legislation has had the intended effect of making schools think differently about EOTC. But the process of documenting compliance makes them ‘overly cautious’ and is perceived as burdensome and largely unhelpful. The amount of extra paperwork in addition to all the other work involved in EOTC planning was a common complaint:

The main constraint is the ridiculous amount of paperwork now necessary to comply with relevant legislation. (PS29, NEOTCQ)

And they probably need to stop making the paperwork get more and more and more, otherwise it is going to reach the stage where people say we are not actually going to bother doing this. (SS Staff Focus Group)

Pretty monotonous there’s a lot [of paperwork], I didn’t get any extra time for that role so to find the time to do all that, as well as planning classes was hard, so just that’s a barrier (SS Staff Focus Group)

Concerns about the quantity of paperwork, the repetitive or monotonous nature of this work and the feeling that paperwork was creating an obstacle to the provision of EOTC were frequent both in the survey responses and in the individual interviews and focus groups. We identified three approaches to this challenge: stopping providing EOTC; superficial compliance to save effort; and creating systems that minimise the barrier and maximise the relevance of paperwork.

Avoidance of paperwork through halting EOTC

As noted above, one response to the growing amount of paperwork might be stopping EOTC altogether, and the following comments support this line of thinking:

We are starting to see trends where staff are no longer available to do EOTC due to the massive impact on their time. This has largely related to the increased workload due to new legislation. (SS5, NEOTCQ)

[An] increase in paperwork, compliance etc … undoubtedly discourages some staff from taking trips and will make some trips less feasible. (SS3, NEOTCQ)

As teachers, we are now facing an overall increase of administrative workload/paperwork. These additional tasks have eaten into the finite amount of time we have to do our job and have required teachers and staff to use their own time to facilitate this. As teaching is generally a thankless job, this ‘becomes old’ very quickly and things have to give. I believe EOTC has become one of those things. (SS29, NEOTCQ)

The decision to stop providing EOTC solves the problem of the expectations of the law on two fronts: first, it avoids the paperwork associated with EOTC; and second, it means that there are no fears of HSAWA liability from EOTC activities because these are not occurring. As in Part 1, where we found people avoided anxiety about legal liability by simply halting EOTC, we also see evidence of this approach to paperwork. The quotes above indicate that paperwork has caused staff to no longer support EOTC in a context of the increased administrative load of teaching. It is understandable that staff with heavy workloads are reluctant to engage with the extra work involved in EOTC. Notwithstanding, there are staff who remain committed to EOTC and who have resolved the work associated with paperwork differently.

Box-ticking and butt-covering: disengaging with the process and focusing on the product.

Another approach to the quantity of paperwork is to complete it with as little effort as possible. The digital workplace may enable this approach. While the evidence for this did not manifest directly in the responses, there are a range of comments on the irrelevance of paperwork for student safety, referred to as ‘box-ticking’ and ‘butt-covering.’

It is just the box ticking and the butt covering that drives us nuts. Because to my mind, the box-ticking and the butt-covering does not add or subtract anything from the kids. It just provides a barrier and a burden for us. I am not saying that we shouldn’t be safe with our kids, and we always have been, but it’s just what I see as just butt covering. It is just covering our butts so that if something does go wrong, someone can be blamed and that is what frustrates me the most. (SS Focus Group)

The quote highlights that paperwork can become evidence in the media and a court and could be used to castigate and prosecute individuals and the school. The notion that compliance becomes solely a means of protection from legal liability (box-ticking and butt covering) is a concerning outcome of enactment of the legislation in social and cultural settings. Also, as discussed earlier, assuming paperwork will mitigate legal liability is misplaced if the contents of the paperwork and what happens in practice do not align. It seems that there is an awareness of this possibility among some EOTC coordinators and school leaders:

There is this huge confusion about what paperwork is, and I’ve been working really hard to try and explain to people it’s not about giving me a piece of paper with RAMS analysis on it. It’s about actually doing it [the analysis] … .he [the teacher] you know gives me a big piece of butchers paper, that he’s got all the kids on [involved], which is awesome. (SS Staff Focus Group)

This clarifies that the purpose of paperwork is not to simply hand over a completed piece of paper for sign off, rather it is about the analysis behind that work and ‘actually doing it.’ In this case, a RAMS form (Risk Analysis Management System) is a template form structured to prompt people to consider risks, causal factors and mitigation strategies among other aspects and as suggested, is not what the person wants. The example they provide in the quote, is of another teacher who completes the trip plan on a poster-sized piece of ‘butchers’ paper together with their students. This statement underlines the importance of the process over the product of the writing, and the importance of the educative aspects of including students. The legislation makes it clear that safety is the responsibility of all parties, yet students are often left out of the process to become mere receptacles. Hence a valuable learning opportunity is gained by including students in considering risk reduction strategies.

Mitigating the paperwork through creating an effective process

A number of respondents either disagreed or were neutral to the statement that paperwork and workload reducing the provision of EOTC. These participants commented on safety management systems and associated roles and responsibilities including school EOTC coordinators that allow them to manage EOTC effectively without paperwork becoming onerous.

We also have good systems to ensure that there is good risk management in place. (PS188, NEOTCQ)

We have improved our paperwork, so it is easier to fill in and is more accurate, staff are supported well by the teacher in charge of EOTC. (SS32, NEOTCQ)

At [our High School] we have a very robust EOTC process and at this stage have stayed up to date with the [HSAWA], Vulnerable Children’s Act and we keep trips to be as equitable as possible, so parents are still mostly willing to contribute to the donation proportion of the activity, event and or trip. Staff are given one to one assistance to understand the expectations of their EOTC application so most buy in and processes are sound. (SS30, NEOTCQ)

These quotes are representative of many schools where there are systems or processes in place which enable them to integrate compliance into their normal planning. As part of such an approach, safety management paperwork was considered appropriate and easy to complete. There was clear guidance on managing risk effectively, and teachers were supported to understand and apply these processes. Some schools have moved to online systems:

[Our] High School has developed a paperless EOTC Documentation system which has greatly reduced the paperwork load and enhanced the approval process and pre-vetting of Outdoor Ed providers. It is called Trip Planner, and it is a dedicated module which is part of a Health and Safety Management tool called Safety Seek. It has revolutionised our EOTC compliance processes. (SS124, NEOTCQ)

Consistent with digital workplaces, schools are increasingly moving to online systems for many aspects of their student management and operations. It is understandable that they would invest in online safety management EOTC documentation systems. As the SS124 above states, ‘it has revolutionised our EOTC compliance processes.’ EOTC can also be enabled by more simple systemic factors such as utilising blanket consent for low-risk trips during school hours.

Well, that’s the thing like at the beginning of the year, all parents sign a form you know at the school to say children are allowed to go on local trips. So, we don’t have to ask every time. So that way we are you know, when the weather’s nice and it’s not too hot, we are free to go a little trot round the block, or go and do our writing in the bush, you know things like that. (PS144, Staff FG)

Systems are not created, maintained, or administered without the input of people. One role that was mentioned frequently was that of school EOTC coordinators, who appear critical in supporting and enabling EOTC. They also play a role in effective EOTC systems as indicated below.

Having a person that is designated to run and oversee EOTC – somebody who is there to pick up pieces in terms of filtering through information around Health and Safety so that we know we’re being compliant. Somebody who is helping and assisting with budgeting, with staffing – even the making sure that we’re got our First Aid Certificates up to scratch – somebody who does all of that organising for the big school camps and somebody that the staff can go to when they’re organising their day trips or their speakers or their walk up the mountain or whatever it is as well as the overseas trips. It makes a massive difference. (CS3, Staff FG)

And again, I’m congratulating [EOTC Coordinator] here, what he’s set up in the school is a process that is very thorough and rigorous, where no activity is undertaken without the question, the hard questions asked … There’s always a plan for what they want to achieve through that particular experience, and we contract people in to do what we need to, and it is well thought out, and it is well planned, and it doesn’t just happen, there’s a process, a very thorough process that we go through, and the board trust that process, and they trust the staff. (SS96, Staff FG)

These comments highlight how important EOTC coordinators are for effective EOTC management systems, particularly in large schools. Noteworthy is that the BOT trusts the process and the staff. However, there is recognition from some schools that there may not be resources for EOTC coordinators, and that principals often pick up these roles.

There is pressure on EOTC coordinators or similar to ensure all processes and procedures are in place and followed. This is a funding issue for most schools, to have a specialist person in this role with adequate time allowance is rare. (CS3, NEOTCQ)

Although not all schools have adequately resourced EOTC coordinators, it is clear to see how effective people in a dedicated role can enable EOTC through the many responsibilities they fulfil alongside managing EOTC systems.

And, yeah it, you know there are audit checks done around everything which goes out but we have tried to approach our processes in such a way that everything is as simple as possible for staff in terms of drawing information and making sure they have the right approach, the right information with them it in order to utilise it if they need to …(SS Focus Group).

I know as a school we took all those forms and created a system where we went – staff go to this link, fill in the form – it’s on Google Forms and if they tick an overnight box, or they tick they’re using the external providers – boom, it jumps into the section … And we have had a bit of feedback from staff— once they got a handle on the system and got used to the whole paperwork that that’s become really good and you’re like sweet. (Non-Specified School, Focus Group)

Findings summary

This section has identified three plausible approaches which mitigate the challenge of paperwork; first, avoidance through no longer running EOTC; second, disengaging with the process and simply viewing paperwork as a performative ritual; and third, creating a system whereby paperwork is minimised and, where paperwork is done, it is seen as relevant. Effective systems often are often associated with a dedicated role in the school that supports teachers to understand the processes and coordinates EOTC.

Discussion

We have drawn from literature that shows the relationship between legislation, student safety and compliance through paperwork. It seems that when legislation is introduced, there is a period of creative responsiveness from the affected actors and organisations to develop systems of compliance which become established as accepted practices (Suchman & Edelman, Citation1996). In the case of HSAWA the compliance takes the form of paperwork which ideally should promote thinking and support planning but also will be used as evidence in the event of a serious incident or accident. It is beyond the scope of this research to determine if safety improves through this process.

The intentions of the HSAWA are to keep people safe and healthy. There are multiple and often unforeseen consequences when laws are interpreted by organisations and individuals in society. High levels of accountability such as those enforced by safety legislation where everything is checked and signed off can lead to staff feeling they are working in a low trust environment. Regulation inevitably increases control of teachers work and audit mechanisms of scrutiny and control (Troman, Citation2000). These mechanisms can undermine a sense of professionalism and may lower workplace morale (ibid). Some participants in the present research, particularly where programmes were under pressure certainly reflected low morale. Arguably, the focus on compliance and accountability has become the preoccupation for many schools.

A finding of this research is that a large number (44%) of schools find the legislation a barrier to EOTC and 45% reported the associated paperwork as a barrier. Quantitative results suggest that these are not the same cohort. This finding to some extent supports anecdotal evidence which suggested that EOTC was no longer considered tenable by a concerning number of schools. It is possible that safety may be improved but it comes at the cost of workload and fear of legal consequences.

On the other hand, 35% of respondents and their organisations reported the legislation was not a barrier to their curriculum and paperwork was manageable and their EOTC provision was not negatively affected. What this means is that these respondents were able to align their focus on student learning and safety with the supporting dimensions of legal responsibilities, staff competency alongside compliance and paperwork. The remaining 20% neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement. Most schools reported increased staff anxiety levels whether EOTC programmes were affected or not. We found a small amount of support for the law positively changing how people approached or thought about EOTC.

The work of Lilley et al. (Citation2021) suggests that the overall impact of the HSAWA legislation in reducing workplace fatalities in industry was not significant. We lack the data to confirm the position for EOTC and this would be worthy of further research. Anecdotally, the law has sharpened the minds of educators about safety. It is hard to argue against a strong safety focus, but the present research shows that the mechanism of compliance through writing is creating tensions.

The literature proposes that writing can stimulate thinking but largely when the writing is seen as a process and not a product. This is because writing to create a product focuses more on correctness of output and meeting external goals and not the stimulation of new thinking and real-world application. Paperwork in EOTC has been criticised previously as Brookes (Citation2018, p. 26) makes clear: ‘The most common systemic problem in the OE field by far, based on fatality cases, is a tendency for organisations to deploy staff with insufficient expertise, and to over-rely on procedures, rules, and written guidance.’ Brookes highlights that paperwork and procedures cannot and should not replace competent staff. Similarly, ‘risk assessment’ should be seen as a verb not a noun (Barrett, Citation2020), meaning it should be applied and active and not just a document written, submitted, and filed. The findings combined with the literature points to a possible intersection for teachers who frame paperwork as a pointless box-ticking and butt-covering exercise and view paperwork as a product; a ticket past the ‘EOTC gatekeeper’ who is generally the BOT, principal or EOTC coordinator. According to lawyer Smith (Human Dimensions, Citation2023) such a practice should be considered in relation to the increased legal liability created by the paperwork for the school rather than considering paperwork as a mitigation strategy.

There is evidence that the process of completing paperwork, and the process of planning for student learning and safety are disconnected for some teachers (box-ticking and butt-covering). This can potentially lead to teachers viewing paperwork as best completed with as little effort as possible. Such an approach can reduce the cognitive load of teachers and allow them to get on with the important work of providing EOTC experiences for their students. While minimal effort manages the situational demands, it defies any sort of deep neural activity that links to clear thinking, memory retention and effective learning (Galbraith & Baaijen, Citation2018). In effect, planning is short-changed and the potential for human error intensified.

A number of schools reported moving to electronic safety systems consistent with almost all industries that have become digital workplaces. But by moving to computer-based systems, are we interrupting the essential deep-thinking processes that link writing, learning and practice? The rise in the ability of artificial intelligence (AI) to generate text has further heightened concerns that production of documentation (paperwork) can be largely disconnected from thinking. We do not see a lack of quality and self-completed paperwork as evidence of a lack of thinking. But we are concerned that when a superficial treatment of planning and preparation becomes a ritualised performance, important safety steps are likely to go missing. This omission leaves individuals and organisations fundamentally non-compliant with the HSAWA. In such cases, paperwork becomes a legal liability for the school.

More important than legal expectations in our view is that teachers have a moral and ethical duty of care for students. We do not equate an aversion to paperwork as necessarily a sign that there is a deficit in these educators’ care for students. What we do question is whether or not there are systematic procedures to support these educators to provide EOTC learning that is safe. The perception of paperwork as punitive or at best viewed with resigned submission is a challenge to quality EOTC.

Findings indicate that some respondents have chosen to stop providing EOTC because the paperwork has become too onerous. This is in addition to the findings in Part 1, where anxiety about legal liability was reducing EOTC provision. It is not possible to completely untangle the influence of paperwork versus the impact of anxiety over legal liability, however the cumulative effect on EOTC is substantial, and in many cases is resulting in teachers deciding to halt EOTC. The cost of this decision is the loss of EOTC, which has a well-evidenced body of research showing the benefits to student learning (e.g. Hill et al., Citation2020). We consider this a significant and avoidable loss which can be overcome.

Quality systems sitting alongside highly competent staff are critical to student safety (Brookes, Citation2018). Competent staff can be developed through pre-service teacher education, yet this appears increasingly marginalised (Hill et al., Citation2020). In-service education is also important and EOTC coordinators play a critical role. Without these mechanisms in place EOTC is likely to be viewed as too hard, too risky or be inadequately planned for.

It is our responsibility as a community to ensure our students are kept safe while they learn. EOTC contexts do provide more dynamic and less predictable environments than classrooms, which is to some degree also linked to their heightened pedagogical potential (North et al., Citation2022). The HSAWA does not require steps beyond evidence of the normal diligent planning required for learning and safety. Therefore, compliance with the laws should not be viewed as onerous. What is different to normal planning are the perceived threats of punishment. Our findings show that perceptions of legal punishment have added an additional burden of anxiety to school staff. It appears vital that the heightened focus on the potential for punishment does not detract from thorough EOTC planning or erode the good will and energy of committed school staff.

Conclusion

This research highlights how paperwork can be a barrier to EOTC programmes and explores the contested relationship between the dimensions of a safety system including student safety and effective learning, legislation and paperwork. Regardless of the barriers, some schools are coping well in the new environment and have exemplary programmes, excellent systems, and competent staff members. These schools provide beacons of hope for those who are struggling. It is noted that school context (e.g. type, location and decile) will have an impact on implementation and being well-resourced appears to be an advantage.

Part 1 of these articles analysed the relationship between legislation and student safety and Part 2 examined approaches to paperwork and compliance. The neoliberal milieu demands significant accountability through legislative requirements. The relationship between student learning and safety, legislation and paperwork can be aligned and coherent, or misaligned and result in dysfunctional, ritualistic approaches.

It is important that the paperwork supports a thinking process and is not just seen as a product, at worst a pointless exercise in accountability which is unrelated to the activities at hand. Careful planning must encourage deep thinking whether that be through a written or some other process. The completed plan becomes the modus operandi of the educator and is intrinsic to competent practice. Most educators use previous documents as a starting point for their future planning. Written plans are evaluative vehicles for learning in hindsight and support educators during the EOTC event and (re-)planning for future events. We harbour concerns that the production of efficient digital systems and AI will significantly undermine the thinking processes required for quality planning and believe this warrants ongoing research attention.

Earlier research demonstrated the high value placed on EOTC in Aotearoa New Zealand (Hill et al., Citation2020). Given that fatalities have occurred in EOTC, we consider due diligence and evidence of risk assessment processes and thinking is reasonable. After all, we are given the responsibility for educating other people’s children in the best way possible. For this to continue, we need to ensure that staff members are experienced and qualified. As Brookes (Citation2018) believes, it is impossible to replace inexperienced staff with good paperwork. Effective pre- and in-service professional development appear critical to developing and maintaining competent staff. Additionally, it is essential that competent staff are supported with effective safety systems and processes, including paperwork and the support of skilled EOTC coordinators. Importantly, this research has found that creating systems that minimise the barriers and maximise the relevance of paperwork are very much needed within schools. In this way, generations of students will continue to benefit from the powerful learning experiences offered by EOTC.

Part 2 reviewer feedback and responses.docx

Download MS Word (14.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2024.2372391

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Allen Hill

This article is part of the findings of the Comprehensive National Study of EOTC which involved a multi-centre research group in Aotearoa New Zealand. The group are committed to realising the potential for student learning beyond the walls of the classroom both nationally and internationally. The research group are continuing to closely examine the current state of practices in schools and also critically explore opportunities for developing and improving this valued area of education.

Notes

1. Aotearoa New Zealand is a style convention of the NZ Government out of respect for the indigenous Māori people and the bi-cultural and bi-lingual context of this country.

References

- Anderson, S. K., & Terras, K. L. (2015). Teacher perspectives of challenges within the Norwegian educational system [Article]. The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 14(3), 1–16.

- Arnold, K. M., Umanath, S., Thio, K., Reilly, W. B., McDaniel, M. A., & Marsh, E. J. (2017). Understanding the cognitive processes in writing to learn. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 23(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000119

- Barfod, K. S., & Bølling, M. (2022). Anticipated bias in education outside the classroom research – do we promote representative participation?. 9th International Outdoor Education Research Conference (IOERC), Amberside, United Kingdom: University of Cumbria. https://ioerc9.org/

- Barrett, A. (2020). Does documentation save lives -Or Do People?. https://www.ecoportal.com/blog/health-safety-documentation

- Bluff, E., & Gunningham, N. (2012). Harmonising work. health and safety regulatory regimes. Australian Journal of Labour Law, 25, 85–106.

- Boyes, M., Potter, T., Andjkaer, S., & Lindner, M. (2018). The role of planning in outdoor decision making. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 19(4), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1548364

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Brookes, A. (2018). Preventing fatal incidents in school and youth group camps and excursions: Understanding the unthinkable. Springer.

- Brown, P., & Calnan, M. (2009). The risks of managing uncertainty: The limitations of governance and choice, and the potential for trust. Social Policy & Society, 9(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746409990169

- Court, M., & O’Neill, J. (2011). ‘Tomorrow’s Schools’ in New Zealand: From social democracy to market managerialism. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 43(2), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2011.560257

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Dallat, C., Goode, N., & Salmon, P. M. (2018). ‘She’ll be right’. Or will she? Practitioner perspectives on risk assessment for led outdoor activities in Australia. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 18(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2017.1377090

- Evans, J. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629

- Ferrell, K. G. (2007). Documentation, part 2: The best evidence of care. The American Journal of Nursing, 107(7), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000279271.41357.fa

- Fitzgerald, S., McGrath-Champ, S., Stacey, M., Wilson, R., & Gavin, M. (2019). Intensification of teachers’ work under devolution: A ‘tsunami’ of paperwork. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(5), 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618801396

- Galbraith, D., & Baaijen, M. (2018). The work of writing: Raiding the inarticulate. Educational Psychologist, 53(4), 238–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2018.1505515

- Goldberg, N. (2005). Writing down the bones (13th ed.). Shambhala.

- Gunningham, N. (1999). Integrating management systems and occupational health and Safety Regulation. Journal of Law and Society, 26(2), 192–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6478.00122

- Haridy, R. (2020). EEG study finds brain activity differences between handwriting and typing. https://newatlas.com/science/brain-activity-differences-handwriting-drawing-typing/

- Hayes, J. R., & Nash, J. G. (1996). On the nature of planning in writing. In C. M. Levy & S. Ransdell (Eds.), The science of writing: Theories, methods, individual differences, and applications (pp. 29–55). Erlbaum.

- Hill, A., North, C., Cosgriff, M., Irwin, D., Boyes, M., & Watson, S. (2020). Education outside the classroom in Aotearoa New Zealand – a comprehensive national study. Ara Institute of Canterbury Ltd. https://www.eonz.org.nz/assets/Resources/Research/EOTC-in-Aotearoa-New-Zealand-Final-Report-2020-compressed.pdf

- Hirsh, Å. (2014). The individual development plan: Supportive tool or mission impossible? Swedish teachers’ experiences of dilemmas in IDP practice. Education Inquiry, 5(3), 24613. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v5.24613

- Hogan, R. (2002). The crux of risk management in outdoor programs — minimising the possibility of death and disabling injury. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 6(2), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03400758

- Human Dimensions. (2023). Risky conversations: #3 paperwork [Video]. https://vimeo.com/showcase/3938199

- Jingshan, C., Hailong, S., Chenjie, X., & Aimei, L. (2019). Why information overload damages decisions? An explanation based on limited cognitive resources. Advances in Psychological Science, 27(10), 1758–1768.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow (1st ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. https://go.exlibris.link/gnK3hbJ2

- Karseth, B., & Møller, J. (2020). Legal regulation and professional discretion in schools. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(2), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2018.1531918

- Lamott, A. (2020). Bird by bird: Some instructions on writing and life (digital ed.). Canongate Books.

- Leijten, M., Van Waes, L., Schriver, K., & Hayes, J. R. (2014). Writing in the workplace: Constructing documents using multiple digital sources. Journal of Writing Research, 5(3), 285–337. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2014.05.03.3

- Lilley, R., Maclennan, B., McNoe, B. M., Davie, G., Horsburgh, S., & Driscoll, T. (2021). Decade of fatal injuries in workers in New Zealand: Insights from a comprehensive national observational study. Injury Prevention, 27(2), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043643

- Mannion, G., Mattu, L., & Wilson, M. (2015). Teaching, learning and play in the outdoors: A survey of school and pre‐school provision in Scotland: Scottish natural heritage commissioned report number 779.

- McLeod, S. A. (2007, December, 14). Levels of processing. Simply Psychology. www.simplypsychology.org/levelsofprocessing.html

- Ministry of Education. (2016). EOTC guidelines 2016: Bringing the curriculum alive. Learning Media Ltd.

- Ministry of Education. (2020). Ministry funding deciles. http://parents.education.govt.nz/secondary-school/secondary-schooling-in-nz/deciles/

- Murphy, M. (2022). Taking education to account? The limits of law in institutional and professional practice. Journal of Education Policy, 37(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1770337

- North, C., Cosgriff, M., Boyes, M., Irwin, D., Hill, A., & Watson, S. (2024). The work that the law does in education outside the classroom: Part 1 – the law and student safety. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2024.2372387

- North, C., Hill, A., Cosgriff, M., Watson, S., Irwin, D., & Boyes, M. (2022). Conceptualisations and implications of ‘newness’ in education outside the classroom. Cambridge Journal of Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2022.2094893

- Suchman, M. C., & Edelman, L. B. (1996). Legal rational myths: The new institutionalism and the law and society tradition. Law & Social Inquiry, 21(4), 903–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.1996.tb00100.x

- Sullivan, R. (2006). The dangers of safety in outdoor education. New Zealand Journal of Outdoor Education: Ko Tane Mahuta Pupuke, 2(1), 5–17.

- Sullivan, R. (2014). A review of New Zealand’s EOTC policy and curriculum: Changing meanings about safety. Curriculum Matters, 10, 73–93. https://doi.org/10.18296/cm.0176

- Sullivan, R., Carpenter, V., & Jones, A. (2011). ‘Dreadful things can happen’: Cautionary tales for the safe practitioner. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 15(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03400911

- Swarts, J. (2010). Recycled writing: Assembling actor networks from reusable content. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 24(2), 127–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651909353307

- Troman, G. (2000). Teacher stress in the low-trust society. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 21(3), 331–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/713655357

- Wastney, M. (2018). Buried in paperwork. New Zealand Education Review, 9(1), 6–7.

- White, E. M. (1993). Assessing higher-order thinking and communication skills in college graduates through writing. The Journal of General Education, 42(2), 105–122.

- Worksafe, N. Z. (2017). Writing health and safety documents for your workplace. https://www.worksafe.govt.nz/the-toolshed/tools/writing-health-and-safety-documents-for-your-workplace/

- Zink, R., & Leberman, S. (2001). Risking a debate–redefining risk and risk management: A New Zealand case study. The Journal of Experiential Education, 24(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590102400110