Abstract

In this paper we draw on three studies of social class change amongst the middle classes undertaken in London over the last 25 years to reflect on the changing values expressed by respondents to school choice. We argue that there has been a hardening of attitudes to school performance and a loss of middle-class autonomy towards schooling. Increasingly we note a concern to navigate the few areas of privilege in a school system designed for working class children but now expected to cater for a vastly increased and educationally-anxious middle class. We specifically address the way in which choice of school has become enshrined in legislation but has itself become constrained by the lack of places in popular schools. We argue that the consequence has been to diminish the amount of choice and ensure that ‘distance from school’ becomes the sole arbiter of access to most popular schools. Thus an attempt at widening access to education has in effect restricted it to those able to access the housing markets nearest to the most popular schools. Taken together with a series of policy interventions designed to circumvent middle-class families playing the system, this has in effect reduced the element of choice by forcing most parents to play for the ‘safe option’ in the fear of being allocated to something worse. We conclude by suggesting that this policy is unsustainable in the longer term and suggest that the government policy of building new Academies is a means of re-engineering London's system of secondary education to reflect the aspirations of those living in its recently gentrified areas.

Keywords:

Introduction

Ask me my three main priorities for government, and I tell you: education, education, education.

This is a country of aspirational individuals who, given half a chance, want to get on and not simply get by.

Increasingly, as sociologists of education have shown (Ball Citation2002), the middle classes were forced into an explicit culture of strategising in order to identify appropriate routes into the high-achieving schools – whether in the state, private or faith sector – and in investing considerable amounts of time as well as economic, cultural and emotional capital to realise these strategies. A situation in which middle-class privilege was relatively effortlessly passed on through the education system therefore began to change in the 1980s. The change process was partly driven by the increasing size and diversity of the middle classes wedded to the importance of education in ‘getting ahead’ in a professional and managerial labour market and partly ‘pushed’ by the increased competition between schools fostered by the publication of school performance statistics, a results-driven financial model and an increasingly robust inspection regime by the Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED) whose reports were made available on the internet and which, under its early director Chris Woodhead, did not flinch from criticising poorly-achieving schools in very robust terms.

This situation was particularly acute in large cities and nowhere more so than in London whose population has become increasingly middle class as gentrification has taken hold (Lees et al. Citation2007). The competition for places in well-performing schools became increasingly intense as more middle-class parents chased relatively fewer places in a city whose education system remains dominated by its working-class heritage. Although the middle class have traditionally exercised choice of schooling both within and between the state and private sectors, the notion of school choice only became formally enshrined in public policy with the 1988 Education Act which recognised the right of parents to send their children to a school of their choice. However, just as the right to do what the middle class had always done was recognised, it became increasingly difficult to achieve because of the growing pressure on the system. Choice has now become the means of rationing demand for the insufficient supply of popular school places in many parts of London. Distance from school has become the arbiter of who gets what. Whilst the origins of this lay in the 1988 Act, it is only in recent few years that ‘where you live’ has really come to determine ‘what you get’; previously, as many studies have shown, the middle classes were able to negotiate their way around such restrictions (Power et al. Citation2003).Footnote2

Our aim in this paper is two-fold, firstly to demonstrate that where you live increasingly determines not only your options for schooling but also, crucially, your chances of fulfilling them and secondly that the importance of education in influencing decisions about where to live is, as a consequence, becoming more central to many London middle-class households. Many first and indeed second-generation gentrifiers were much more relaxed about where to live than would now be possible. Increasingly housing and education markets in London are becoming entwined with those able to access the rapidly-inflated house prices in the catchments of popular schools being the ones best able to exercise their choice of school for their children. Having obtained this for one child, the ‘sibling [priority] rule’ generally ensures that this right extends to younger brothers and sisters.Footnote3 The role of parental choice, a mantra uttered by politicians of all major parties, in reality offers parents an opportunity to express a preference whose likelihood of being fulfilled is increasingly determined by where you live.Footnote4

In the remainder of this paper we examine how middle-class parental aspirations for their children's education have hardened over the last 25 years in London by reference to three in-depth studies of social class change in inner and outer London that were conducted respectively in the late 1980s, the late 1990s and the middle years of the first decade of the present century.Footnote5 These studies and the research monographs which resulted are summarised in and represented in .

Table 1. The evidence base.

We argue that since the late 1980s, middle-class parents have become increasingly anxious about achieving the best – as opposed to the optimal – schooling for their children; increasingly this has applied at primary and not simply at secondary school level. We suggest that ‘circuits of schooling’ (Ball et al. Citation1995) have become increasingly hedged about so as to constrain schools from offering places to all but the most clearly-entitled which increasingly means the financially, and hence geographically, privileged. In conclusion, we argue that within the state non-selective sector, choice has frequently become ‘no choice’ and that parents are playing safe by choosing the most popular schools which they think they are most likely to get their children into. The overall result may have been to increase the sense of collective failure amongst parents, children and, in all but the most popular and successful, schools themselves – this we suggest accords with increasing tendencies within neo liberalism to transfer the responsibility from the state to the individual.

Contemporary London is very different from that of the immediate post war years when the foundations were laid for its welfare structure including the provision of education and schooling. No longer a predominantly white working-city city, roughly a third of its current population is non white and the largest single occupational class can broadly be described as middle class (more accurately perhaps middle classes) (Butler and Savage Citation1995, Savage Citation2000, Butler and Watt Citation2007). In 1971 the middle classes were under-represented in London – particularly inner London; this pattern has now reversed such that inner London now has the highest proportion of these groups compared to the rest of the UK. London not only differs in its social structure from the rest of the country but internally it is highly diverse in terms of social class, ethnicity and their associated habituses (Butler and Hamnett Citation2011). This difference between London and elsewhere and within the city itself is central to our discussion about educational provision – levels of provision and attainment vary dramatically across the city but what is shared is the fierce competition for schooling which is increasingly determined by distance from school.

One crucial difference between the old white working-class London and the new and much more diverse non-manual middle-class city lies in the way in which they express their aspirations which are increasingly geared towards individual achievement and particularly the gaining of educational credentials for their children – see Raco Citation(2009) for an excellent critique of the culture of aspiration. The relationship between social class, educational attainment and performance has long been the staple for the sociology of education and debates about educational policy which we do not have the space to repeat here other than to assert that, following Ball et al.'s concept of ‘circuits of schooling’, it has become increasingly geographically-based (Ball et al. Citation1995, Gewirtz et al. Citation1995). In the remaining three sections of the paper, we discuss how these approaches to schooling have changed over the last 25 years by drawing on three separate London-based research projects undertaken at the beginning, middle and end of this period.

The ‘Pioneers’

The gentrificaiton of London in the 1970s was ably depicted in the ‘Life and Times in N1’ cartoons in The Times by Marc Boxer which was a thinly-disguised caricature of the journalist Nicholas Tomalin and his ilk (Carpenter and Lees Citation1995). Almost entirely comprising childless singles or cohabiting couples, this group made few demands on the schooling system. Indeed more were probably school teachers than parents, attracted by the idea of contributing to the education of the working class and living and working in a deprived area. Butler Citation(1997) notes amongst his interviewees in Hackney in the mid 1980s growing numbers with pre-school age children. Most claimed that they were attracted to the area because of its housing and its ‘counter cultural’ ambience (Ley Citation1994); education was almost never offered as a reason. Most had lived in the area for some time, often arriving as graduate students and working their way up through shared student flats, to their own flat shared with a partner or friend, to a bought flat and ultimately perhaps to a house. Their attachment was to ‘people like us’ and, if the subject of schooling was broached, they were confident that they could negotiate a satisfactory outcome or if not that they could ‘buy their way out of trouble’. Some respondents were teachers, many worked in and had a commitment to the public sector or, if not, they had the resources to make alternative plans; what they shared was a confidence in being able to negotiate the pitfalls in ways with which they were comfortable.

With hindsight, they were amazingly confident about their ability to make the world in their own vision and to use their skills and cultural capital to shape the system to their needs. They believed that – individually or collectively with others in the same situation – they could make the system work for themselves and, at the same time, they could add value for those less fortunate. The fear of the ‘other’ who would ‘drag their children down’ never appeared in the narratives. The problem was seen to lie in the class nature of the education system and the solution lay with progressive educational practices – whole-class teaching, child-centred education and middle-class goodwill that would overcome the traditional deficits associated with working-class education.Footnote6

Thatcher's children?

By the mid 1990s – notwithstanding the severe recession of the early 1990s which called the concept into question with several writers (Bourne Citation1993) – gentrification had become an established pattern of life in London and the pioneers were no longer the ‘trendy apes’ of Marc Boxer's caricature. The second study had, as a specific focus, an investigation of the interaction between the middle classes and their local communities across a range of gentrified neighbourhoods in inner London (Butler and Robson Citation2003a). What was striking was how children and schooling was now a key concern. Partly this was demographic – the singles and dinkysFootnote7 were now partnering up and breeding and their children were now of school age with many approaching the secondary transition – but it was more than simply demographic and class change. A city with a historically-derived structure of working-class educational provision was now being populated by increasing numbers of people for whom not only was education the key to transmitting their relative privilege but also were subject to an increasingly explicit moral imperative ‘to do the best for their children’ which cut across the ethos of a ‘middle-class conscience’ which was apparent amongst the 1980s' cohort.Footnote8 We discovered high levels of anxiety about the inadequacies of the local which varied significantly between our research areas; considerable amounts of energy and time were devoted to devising strategies to compensate for these shortfalls which we attempted to understand by reference to the ‘circuits of schooling’ approach of Ball et al. (Butler and Robson Citation2003a, Citation2003b).

All six research areas () in this research project were different but, with the exception of Battersea, none had any secondary schools acceptable to our middle-class respondents. We contrast the response of parents in Telegraph Hill to the crisis of secondary school choice to that in Brixton and Barnsbury where, despite their differences, they had in common that not a single respondent had a child at secondary school within the borough. If the preferred response in Telegraph Hill was ‘voice’ (Hirschmann Citation1970), that in Brixton was ‘exit’ and in Barnsbury to get out the cheque book; nowhere however was ‘loyalty’ (in other words, making the system work) given a chance. Generally, we found that parents were happy with the local primary school although there was evidence of them ‘adopting’ a particular primary school which had a ‘critical mass’ of middle-class children – our prime example of this was drawn from our work in Telegraph Hill in south east London where the local school (Edmund Waller) had become the default school of choice for the local middle class and the de facto social centre of the local middle-class community. The problem arose when the time came to make the transfer to secondary schooling.

In each area we were able to identify a sub-regional circuit of schooling comprising private schools, selective schools and some non-selective schools from which parents identified a short list of target schools (Butler and Robson Citation2003b). For years, parents in Telegraph Hill had sent their children to Haberdashers Aske School. However, when this became a City Technology College following the 1988 Education Act, its selection criteria changed and it had to recruit from a wider sub regional area and ‘banded’Footnote9 its applicants thus frustrating many of the best-laid local middle-class strategies. Those unwilling or unable to access the area's high-achieving private schools (Dulwich College, Alleyns and Sydenham GPDST) were forced to adopt a wider-ranging strategy of seeking out acceptable secondary schools that involved them and their children travelling widely across south east and central London. Ironically, the local middle class got their ‘local school’ back when, in 2005, Haberdashers Aske Hatcham College became an ‘all through’ City Academy, taking children from 3 to 18. It is now one of the most over-subscribed schools in the country with an applicant to place ratio of more than 12:1Footnote10 and uses a distance from school admissions criterion which privileges those in the Telegraph Hill.

Brixton contrasted quite dramatically to Telegraph Hill, mainly in that it lacked a central focus to the community such as was provided by the primary school in Telegraph Hill. More generally, it was lacking in the kind of social capital found in Telegraph Hill that shared knowledge of educational opportunities and came together to argue for a community secondary school such as Haberdasher's Aske eventually became (Butler and Robson Citation2001). Much of Brixton's appeal to the in-coming middle class lay in its ‘gritty’ urbanity and multi-ethnicity which often evoked the descriptor ‘frisson’ amongst respondents. There was no single primary school that the middle class were able to congregate around: the most favoured (Sudbourne) had a very tightly-constrained catchment area – so much so that a number of parents who had failed to get their child in to Sudbourne agreed to send them to Fenstanton – hoping to inculcate the school with a middle-class ethos such as we noted at Edmund Waller. They failed however to achieve critical mass.

It's difficult to know what to do. Sudbourne is our nearest school, but I couldn't get my daughter in there. A few of us in this street had the same problem, so we decided together to send our kids to Fenstanton, try to bring it up that way … it hasn't really worked, that group of kids have just sort of become an isolated clique in the school in general. It's not ideal …. (White British, female, Brixton)

Nearly two-thirds of pupils are from minority ethnic groups … Fifteen percent of pupils are of white UK heritage. Nearly half of the pupils have English as an additional language and 10% are at an early stage of learning English. … There are 28 refugees, most of whom have come from Somalia. Twenty-five per cent of pupils are on the special educational needs register and nearly four per cent have statements … Twelve per cent of pupils are on the child protection register and a significant proportion are or have been in the care of the local authority. The mobility of pupils is an issue … for example, in Year 10, only 43 out of 84 pupils started in Year 7. A high proportion of the pupils who join the school after Year 7 have been excluded from schools elsewhere. (Office for Standards in Education 2001, p. 8)

Secondary education is a real problem here. The local school (Stockwell Park) has a very bad reputation. The primaries are OK, but it's very hard to find secondaries. This is part of the reason why we have decided to move, which we are doing in six months or so … My husband has been offered a job in [elsewhere in the UK], which is a relief in a way, because that gives us the motivation to move and solve the school problem. If not for that, we would have had to go through the struggle of conscience over education that many of our friends have. The new job has got us out of trouble, really. (White British, female, Brixton)

Barnsbury is the epitome of gentrification yet, at some stage or other, most of Islington's secondary schools have been in ‘special measures’ because they were deemed to be failing. At the time the research was being undertaken, only 29% of pupils across the borough got five (or more) good GCSE's (grades A*–C) compared to 50% nationally; only two other authorities in the country had worse results (Guardian 27 July 2001). Barnsbury is as different from Brixton as it is possible to be in gentrified London but what it shared was that not one of our 75 respondents reported having a child at secondary school in the borough. Unlike the other areas where children were schooled at their local primary school and the ‘crisis’ came at eleven with the transfer to secondary schools, in Islington a migration to the private sector began at seven as the realisation dawned that they would need to pass the competitive examinations to London's elite private ‘public’ schools.Footnote11 Accordingly, a well-developed private ‘circuit’ of preparatory schools designed to feed the children into the preferred private schools – Highgate, Channing, St Paul's, City of London – has developed. Alternatively, and to a lesser extent, routes into preferred secondary state schools were engineered using musical or artistic ability (Pimlico), or academic selection (Henrietta Barnett) or even renting one of the flats in the block opposite Camden School for Girls.

Thus in the space of 10 years between these two studies, a dislocation had occurred between middle-class residential preferences and their local educational provision; attitudes had been transformed from those of conscience, confidence, altruism and ‘getting by’ (optimising) to those of anxiety, strategising and ‘getting ahead’. There was a crisis of middle-class confidence and conscience; it was this that drove the last and most recent research project in which issues of education were fore-grounded.

Aspiration and the pursuit of choice

This recent project focused explicitly on the issue of education and the gentrification process. It was clear to us that gentrification had largely missed two targets in its rampage across the inner city: East London and the growing minority middle classes. To date, gentrification had been concentrated amongst the white middle classes despite growing evidence that many of the mainstream professions were recruiting heavily from minority (particularly Indian Asian) groups. In this project therefore we were interested in why there was so little attention being paid in the research literature to non white middle-class groups and to the role played by education. East London was thus a natural focus in the sense that it had apparently been transformed from a working class area but not to a gentrified white middle-class one. Whilst East London might be London's last ‘gentrification frontier’ it might also be one that the white middle classes were avoiding precisely because of a ‘toxic mix’ (as they might perceive it) of educational failure, working-class heritage and recent minority ethnic settlement. None of these in themselves were barriers to gentrification – Hackney, Battersea and Islington, for example, were at the heart of old working-class London and the appeal of Brixton lay precisely its multiculturalism. However these factors in combination with the growing emphasis on educational attainment and fear of an educational underclass might, we reasoned, ‘trump’ its housing market advantages – one of the last large areas of un-gentrified inner city terraced housing in London.

The research took place in the aftermath of New Labour's third successive election victory in 2005 and a 10-year focus on ‘education, education, education’ in which social aspiration had become embedded into a policy agenda of choice in a series of emerging ‘markets’ – including those for health, housing and education. In addition to the analysis of large scale data sets, 300 respondents completed a questionnaire and 100 in-depth interviews were undertaken. What emerges, from this, in relation to education has been a set of unintended consequences in which the geography of place appears to be displacing the sociology of social class in terms of access to education – except of course that the geography of place is largely a matter of the economic resources that can be brought to bear on the housing market. We show in the remainder of this section how education plays a determining role in three very different research areas across East London but in rather different ways depending on the mix of social class background, ethnic group membership and the pre-existing educational infrastructure. However, what they have in common is that it is distance from what are regarded as popular schools that matters unless you are able to trade financial resources or faith assets to negate the increasingly powerful hold that geography plays over choice. The three areas are located on a transect running north east from inner East London – Victoria Park (inner London), Newham (outer inner London) and Redbridge (outer suburban London) and illustrate three very different views of middle-class life and their associated approaches to school choice in contemporary London ( ).

Victoria Park – who buys wins

Victoria Park, as its name suggests, was built in the second half of the nineteenth century to provide the capital's East End with the open spaces afforded to its posh West End. It has been re-discovered as a ‘hidden gem’, over recent years, by the more ‘adventurous’ gentrifiers who have valued its elegant and generously proportioned terraces, slowly pushing out those who occupied its decaying but splendid property. Hackney's premier primary school – Lauriston – is in the middle of the estate; the old ‘board school’ was replaced by a new-build school in the 1980s and was subsequently sold off as upmarket apartments. These have now become highly-valued precisely because of their closeness to the school thus affording privileged access to a school whose catchment distance, in 2008, was 150 metres. Those who failed to get into Lauriston often resorted to faith schools as the second best option –in many cases despite any recent engagement with the faith (Butler and Hamnett forthcoming). However, having secured themselves the best of primary education in the borough, these respondents faced a problem at secondary level and at this stage many – but not all – went private and many of those who did not – either from conviction or lack of resources – gave serious consideration to moving out of London. This was how the following respondents put it when asked why he had sent his children to private school:

… the state provision in Hackney doesn't remotely (stress) equate to the standards that I myself enjoyed that which I wish my children to have. And so the answer is that it's never even really been on the map (stress) of possibilities – sending my children to state schools in Hackney. But, had we lived in Kent or Hertfordshire or somewhere then certainly one may have been able to research and come across state schools that were suitable and would provide the education or provision that you want your children to have. (White, male, Victoria Park north)

Newham: least worst optimisation

In Newham the story varies by ethnicity. There is a two-way traffic in Newham amongst the middle classes. It has become a focus for inbound white middle-class professionals – in many ways a very similar group to that which pioneer gentrified Hackney in the 1980s and Islington and Camden a decade earlier (Butler Citation1997). On the other hand, Newham (the most ethnically-diverse borough in London) is home to a number of long standing minority ethnic groups who lived there for several generations – many of whom have managed to haul themselves up the occupational ladder and are now working in the semi professions (nursing, social work and to a lesser extent teaching).

Whereas the former group is attracted to its terraced Victorian or Edwardian housing and keen to shun the inter or post war suburbs of their upbringing, the latter are equally keen to put distance between themselves and a place they often identify as their first stop in this country and associate with deprivation and discrimination. For them, the suburbs with their ordered semi-detached houses and own front gardens spell aspiration and achievement. Unlike the white incomers, many of the latter felt they neither had the time, the confidence nor the skills to negotiate what they saw as an uncertain market in schooling in Newham which, despite some dramatic improvements, still had a number of very poorly-performing schools. Black African and Black Caribbean parents tended to resolve their concerns by ‘cashing in’ their religious assets and getting their children into faith schools (usually out of the borough). This was not usually an option for Asian respondentsFootnote13 who, in any case, saw aspiration in terms of suburbanisation and moving to Redbridge which not only had semi-detached housing and similar-thinking Asians but also one of the best selective and non selective schooling systems in London. For them, what mattered was a place where your child went to a good school by right. The white incomers into Newham were more prepared to negotiate the social mix of Newham's schools as long as they could avoid the worst schools.

Personally, I would think that the local is almost always the best school for your child because they are going to have friends who are local. So I think it's very important for their independence that they're not driven round. They know their way round the local area and that they can walk to school if possible and which has obviously an environmental impact as well. They can walk and cycle to school. I just think that that's a really important thing and if you think the school isn't very good then you work to make it better, you don't give up on it. And when they say not very good they actually mean doesn't get very high levels for SATs results which is not necessarily the same as not being a good school. (White British, female, Newham)

[How important do you think schooling and education is in terms of their future, career and happiness?]

I think what's the good thing about their schooling is that they are going out into the world having experienced loads of different types of people, from all different cultures and that's going to give them a big advantage when they start work because other people won't have. Other people will have had a really sheltered upbringing – may be they only went to school with other white kids and then they don't know how … you know they don't know what Ede is. You know because they don't have the sensitivity and also because they've mixed with children with disabilities from a very young age. So they're not frightened of someone who is disabled, so they're not … you know I … when I was at school I never saw anyone in a wheelchair, I never saw anyone who had difficulties talking or you know … because they were segregated. I think that they've … because they've had such a mixed environment that they've been brought up in they're going to be … have the knowledge …

Every morning, every morning, every morning, I am asking my two kids when I am taking them to school, how are you going to study after [school]; what are you going to do when you finish your studies? Now I am telling him he is to be a doctor. I have to look after him now so that he will look after me [in the future].

This is a good school, but it should still [be doing better]. Here the kids might get 50 percent but if they get 49 they will fail, in Redbridge they will definitely pass. (Sri Lankan, male, Newham)

Redbridge – in search of the comprehensive ideal

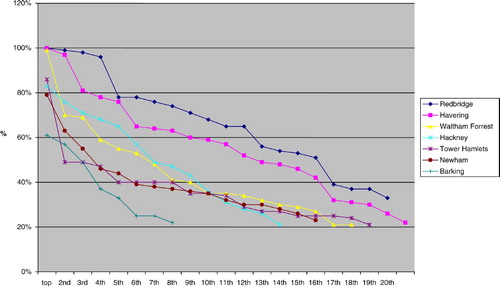

Almost without exception, Redbridge was indeed the ‘promised land’ for our Asian respondents; Redbridge achieves its longstanding educational achievement through a mix of selective and non-selective schools. There are a number of factors that set Redbridge up for this position. Unlike other East London boroughs which might have one successful school and then a relatively long tail of mediocre attainment rates followed by one or two schools with a very poor reputation, Redbridge has a much higher proportion of schools with very good results. illustrates how Redbridge compares with other East London boroughs in this respect.

Figure 2. Percentage of pupils gaining 5 + GCSE's grades A*–C, by borough and ranked school in East London.

Redbridge is however a victim of its own success. There are published catchment areas for its non-selective schools which tend to be very tightly-drawn; however what really matters are the distance-to-school measures. For the most popular schools, such as Seven Kings, parents living within the nominal catchment areas are often disappointed in their first choice. This not unsurprisingly leads some parents to bend the rules. A rise in the availability of ‘buy to let’ flats/houses within the catchment areas of the most popular schools gives rise to what are often perceived as ‘carpet-bagging queue-jumping – this is particularly resented by those living in the area who might have expected to get their children into the school in question.

[How did you get him in there? (son into Seven Kings)]

We did actually [laughing] have to rent a flat out for a whole year, but it was cheaper in the long run than actually sending him to a private school for the long term. It's making a sacrifice – a whole year of rent is like paying a second mortgage but we thought that was better than sending him private which was £14,000 a year, so in the long term it suited us, he is in the school where I wanted him to be. Unfortunately it is a little bit underhand but we had to do it.

Seven Kings is quite a big school but it has a very small catchment so you have to be in specific roadsets, It's not like borough-wide or anything, it's tight, and you do find there are loads of people who are moving in, buying flats etc, specifically to get their kids into the school. Obviously the prices of the houses rise and it has a knock-on effect. (Pakistani, male, Redbridge)

The high standard of attainment in Redbridge's schools overall has created a ‘narrative of popularity’ focused around the best-performing schools which simultaneously demonises others – most of which are in the north of the borough on the peripheral and previously white working-class housing estates. A number of respondents, who had been unsuccessful in achieving their preferred choice of school, found their child allocated to one of these (usually Hainault) and didn't hesitate to express their disappointment. Given the highly-charged issue of educational attainment for many of those who cited this as underlying their choice to move to Redbridge, this reaction was perhaps unsurprising.

If you have a situation which the government proposed, where everybody can choose their school, I mean what's going to happen to schools like Seven Kings? You know that we are going to be able to select the best students, everybody will get A star. And then, you know, it will sort of filter down, and Valentine's will get the next best lot, and Oak's Park will get the next best lot, and then children who end up in Hainault have no chance of going up on the social ladder'. (White British, female, Barkingside)

What I want for my girls – I want the best education there is. But the catchment's secondary school is Hainault Forest, and they are not going there. Over my dead body will they go there!. I'll teach them at home…There's bullying, there's drugs … they were on special measures for a while, I believe they've come off it now. They're changing their name but it's like anything, you know – a change of name isn't, I know they wanna get away from the image of Hainault High, but it was a bad school when I was at school, (White British, female, Barkingside)

Conclusions – loser choosers?

We have argued for the need to add a geographical dimension to the largely sociological discussion about choice in education (West and Hind Citation2006). We have done so by focusing on the ways in which middle-class respondents in different areas of London have adopted a much more strategic and defensive approach to the schooling of their children over the past 25 years. Whilst educational policy has focused around issues of ‘added value’ (i.e. the ways in which schools have improved in relation to the social background of their intake), parents have become increasingly focused on absolute performance (the currency required to access good higher education). As London has become more middle class, the juxtaposition of its increasingly aspirant middle-class population with the heritage of its largely working-class schooling system has become sharper. The language of choice, intended to provide for all what has traditionally been the prerogative of the middle-class few, has inevitably become the means of rationing access to an education system in which the perception is of relatively few high-achieving schools. This is compounded by a situation in which popularity and performance are often, in our view erroneously, conflated. The consequence has been to demonise some schools even where there are signs of improvement and, more often, to transform the majority of schools in the mid-range of the attainment distribution into ones which parents feel are second best. The result is that parents make a genuine choice and fail to get it, usually on grounds of where they live, or ‘play safe’ and go for their nearest school in the fear that otherwise they might get allocated to a worse school. In both cases, they feel dissatisfied. Thus a system which was intended to widen the net of social justice by opening up the best schools to all, appears to have succeeded in restricting them to those who can afford to live near them – in extreme cases by renting as a temporary measure a flat in their immediate shadow.

The middle classes have lost confidence in their ability to transmit their cultural capital in spite of the schooling system. Whilst they apparently choose on grounds of performance, in reality they increasingly appear to choose on grounds of popularity which is not always the same thing and tends to equate with social homogeneity. It might be argued that the Academies programme is ‘re-engineering’ London's education system by building schools with new management and staff and an explicitly different ethos in many inner city areas; in so doing it is not simply wiping clean the educational and reputational ‘slate’. Some will be in socially-mixed ex-working class areas which have been subject to gentrification in which there is a real possibility that non middle-class pupils will be displaced by the rigid application of distance to school regulations. The principle of the ‘distance to school’ criteria in their admissions policies has a ring of social justice to it but, in the context of the more geographically-dispersed disadvantage in such locations, it could be seen as means of cementing middle-class social closure around the education market. By rooting choice in geography, we are in danger of legitimating the creation of new bubbles of urban privilege in which there are decreasing numbers of social encounters between young people from different backgrounds and in which ‘social mix is for dummies’.Footnote14

Like gentrification itself, London's education system is now in danger of becoming more exclusionary and of displacing the already-disadvantaged from the opportunities it might otherwise afford them. That it does so on the basis of choice only illustrates how far we have come in the last 25 years in dismantling the notions of ‘equality of opportunity’ and ‘parity of esteem’ that lay at the heart of the reforms enacted at the end of the second world war. The role of the middle classes has also changed along this journey from being the progressive agents of social change to the, more or less willing, lieutenants of neo liberalism.

Notes

The paper is developed from a key note address by Tim Butler to the ‘Geographies of Education’ conference at Loughborough University in September 2010 organised by Phil Hubbard, Sarah Holloway and Heike Jöns – thanks to them and to those present for raising a number of issues which hopefully are dealt with in the paper. I am also grateful to Gavin Brown for commenting on the draft of the paper before it was sent out to review and to the three anonymous reviewers who made suggestions which I hope have resulted in a better – but certainly shorter – final product. Finally the authors would like to acknowledge substantial contribution to the second project of Garry Robson and also to Sadiq Mir and Mark Ramsden who undertook the interviews for the third (East London) project.

Since 2006 all London boroughs operate a standardised application system which allows you to make six choices for secondary school across London. You are then offered the first choice for which you are eligible. Every school has to publish its admission criteria and, with the exception of selective schools (grammar and faith mainly) which prioritise either ability to score well on entrance tests or membership of a faith, the following are invariably the order in which the criteria are ranked.

1. Statement of Special Education Needs (SEN)

2. In care

3. Sibling at the school already

4. Distance from school2

5. The rest

In reality, the number of places offered to children with SEN or in care is very small, usually well under 10% or less, and the sibling criterion implicitly embodies a distance criterion as older children must have lived close to the school to gain a place. Consequently, the key criterion for the offer of a place is effectively distance to school (Hamnett and Butler 2010). This system has put an end to the middle-class practice of holding multiple offers in different often adjacent boroughs.

The ‘sibling rule’ is designed to ensure that siblings are able to attend the same school if their parents so wish; it grants those with an elder sibling in the school high priority in gaining admission and usually ignores the distance from school; so, if the parents have moved house or the catchment area has become further constrained, these facts are ignored in calculating eligibility.

In reality, as we argue below, many parents are ‘intimidated’ from expressing a true preference because of the very real danger of ending up worse off than if they had simply gone for the ‘local option’.

We acknowledge the support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in their support for two of these projects. The second project was undertaken as part of the ESRC Cities: Cohesiveness and Competitiveness Programme under the title of ‘The Middle Class and the Future of London’ (Grant number L13025101). The third project was entitled ‘Gentrification, Education and Ethnicity in East London’ (RES –000-23-0793).

It would be wrong to give the impression that all the respondents were relentlessly committed to public sector provision. The research was based in two areas of Hackney – Stoke Newington and De Beauvoir Town. In the latter many more respondents worked in the private sector (often at senior levels) and were more open to private provision but were broadly supportive of the idea of public provision and most did not, as yet, have school age children.

DINKYs = Dual Income No Kids Yet.

When I re-interviewed one of my first interviewees in the mid 1990s, a highly successful TV producer who had now become quite wealthy and had moved from Hackney to Islington, he remarked that they were sending their child to the local school (although they clearly could have afforded to have ‘gone private’) because they did not want her to become detached from a sense of belonging to a local community. She had been cared for in her pre-school days by a local childminder who had looked after her with her own children. And they did not want to break that link. ‘Peter’, the respondent, argued that they were not seeking ‘the best’ for their child but rather what he termed the ‘optimal’ solution and social relations were a key part of this. I have no idea if they followed through on this but my point is that this attitude was typical of my 1980s respondents but increasingly atypical in the 1990s.

Banding divides the school population into a number (usually four) equal bands on the basis of ability testing and schools then select their pupils to ensure each band is equally represented.

The highly popular Seven Kings school in Redbridge has an applicant to place ratio of 7.

One of the manifestations of the crisis of education in London is that 20%, as compared to 5% of children nationally, are being educated privately and that it is difficult to get children into private schools.

This dilemma was highlighted by the decision by the MP for Stoke Newington and Hackney North to send her son to the private City of London School for Boys rather than Hackney Downs School: if he had been a year younger, she might have been saved the political embarrassment by being able to send him to the massively popular Mossbourne Academy which in effect replaced it.

One of the faith schools in Redbridge has something like one-third of its intake of Asian background – some are Sri Lankan who were brought up in the Catholic faith but others are treated as exceptions.

An exception to this ‘distance trumps all’ rule might be found in the way in which Black groups have been able to use faith schools. However, the pressure that distance has placed on entry to non-selective schools means that this route to is also in danger of becoming rationed by distance (Butler and Hamnett forthcoming).

References

- Ball , S. J. 2002 . Class strategies and the education market: the middle classes and social advantage , London : Routledge Falmer .

- Ball , S. , Bowe , R. and Gewirtz , S. 1995 . Circuits of schooling a sociological exploration of parental choice of school in social class contexts . Sociological Review , 43 : 52 – 78 .

- Bourne , L. S. 1993 . The demise of gentrification? A commentary and prospective view . Urban Geography , 14 ( 1 ) : 95 – 107 .

- Butler , T. 1997 . Gentrification and the middle classes , Aldershot : Ashgate .

- Butler , T. and Hamnett , C. 2011 . Ethnicity, class and aspiration: understanding London's New East End , Bristol : Policy Press .

- Butler, T. and Hamnett, C., forthcoming. Praying for success: faith schools and school choice in East London.

- Butler , T. and Robson , G. 2001 . Social capital, gentrification and neighbourhood change in London: a comparison of three South London neighbourhoods . Urban Studies , 38 ( 12 ) : 2145 – 2162 .

- Butler , T. and Robson , G. 2003a . London calling: the middle classes and the remaking of inner London , Oxford : Berg .

- Butler , T. and Robson , G. 2003b . Plotting the middle classes: gentrification and circuits of education . Housing Studies , 18 ( 1 ) : 5 – 28 .

- Butler , T. and Savage , M. 1995 . Social change and the middle classes , Edited by: Butler , T. and Savage , M. London : UCL Press .

- Butler , T. and Watt , P. 2007 . Understanding social inequality , London : Sage .

- Carpenter , J. and Lees , L. 1995 . Gentrification in New York, London and Paris: an international comparison . International Journal of Urban and Regional Research , 19 : 286 – 303 .

- Gewirtz , S. , Ball , S. J. and Bowe , R. 1995 . Markets choice and equity in education , Buckingham : Open University Press .

- Hirschmann , A. 1970 . Exit voice and loyalty , Harvard : Harvard University Press .

- Judt , T. 2010 . Ill fares the land , London : Allen Lane .

- Lees , L. , Slater , T. and Wyly , E. 2007 . Gentrification , New York : Routledge .

- Ley , D. Gentrification and the cultural politics of 1968 . Paper given to annual conference of the Association of American Geographers . April 1994 , San Francisco, California .

- Power , S. , Edwards , T. , Whitty , G. and Wigfall , V. 2003 . Education and the middle class , Buckingham : Open University Press .

- Putnam , R. D. 2000 . Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community , New York and London : Simon Schuster .

- Raco , M. 2009 . From expectations to aspirations: State modernisation, urban policy, and the existential politics of welfare in the UK . Political Geography , 28 ( 7 ) : 436 – 444 .

- Reay , D. 2007 . A darker shade of pale? Whiteness, the middle classes and multi-ethnic inner city schooling . Sociology , 41 ( 6 ) : 1041 – 1060 .

- Savage , M. 2000 . Class analysis and social transformation , Milton Keynes : Open University Press .

- Savage , M. , Barlow , J. , Dickens , P. and Fielding , A. 1992 . Property bureaucracy and culture middle class formation in contemporary Britain , London : Routledge .

- West , A. and Hind , A. 2006 . Selectivity, admissions and intakes to ‘comprehensive’ schools in London, England . Educational Studies , 32 ( 2 ) : 145 – 156 .

- Willis , P. 1977 . Learning to labour: how working class kids get working class jobs , Aldershot : Gower .