Abstract

Intra-European family migration has extended the realm in which families live and work in Europe. This paper joins a limited number of recent attempts to analyse family migration using a children-in-families approach [Bushin, N. 2009. Researching Family Migration Decision-Making: A Children-in-Families Approach.” Population, Space and Place, 15: 429–443]. In contrast to existing studies on this theme, our focus is on children's migration decision-making, experiences of step-migration and experiences of separation from parents during processes of intra-European family migration. Little is known about children's views and experiences of step-migration and separation from their parent(s) during family migration. Such experiences have implications for the spatial and temporal construction of family and childhood in Europe, where transnational mobility is increasing. This paper discusses children's experiences of separation in two research contexts, Scotland and the Republic of Ireland, to illustrate common features of the phenomena. The paper analyses family relationships relevant to migration decisions and explains their effects on children's agency, as well as on family integrity itself.

Introduction

The growing number of studies focused on child and family migration has brought the phenomena of living life across international borders increased attention in recent years (NíLaoire et al. Citation2011; Parreñas Citation2005; Tyrrell et al. Citation2012). Research focused on the ways in which children experience migration at different scales and in different contexts has been developing in multiple disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, human geography and law. Some of this work has developed from studies of family migration, with the need to include children in family migration research agendas being recognised (Bushin Citation2009), whereas other work has developed from children's rights perspectives (Ackers and Stalford Citation2004). Increasingly, research focused on children and migration recognises children as active agents in their own lives although it does not always consider the involvement children have in making family migration decisions.

There has been increased interest in family and child migration in Europe specifically in recent years (NíLaoire et al. Citation2011) but children who experience family separation concurrently with transnational migration have received little specific attention in European contexts. This may reflect the ways in which their migrations are perceived. Free movement of EU migrant workers and their families has different characteristics than asylum seeker and refugee migrations to and within the EU, in which the impacts of family separation are well documented (see e.g. Spicer Citation2008; Szilassy and Arendas Citation2007). The physical distances and the length of separation in intra-EU family migration is also different to that which children of migrant workers from Latin America or Mexico to the United States (Dreby and Atkins Citation2012), or from the Philippines to Canada or the Middle East (e.g. Parreñas Citation2005; Pratt Citation2009) experience. In the latter cases, for many families, the legal obstacles and risks involved in travelling back home or bringing family members for visits or settlement are the major determinants of limited contact between family members (Zentgraf and Stoltz Chinchilla Citation2012). However, such studies highlight the situations of children who are ‘left behind’ in the origin country when a parent(s) migrates, usually for employment reasons, and then perhaps re-join their parent(s) in the migration destination country at a later date. The processes of family migration and separation are similar in Europe, even though the scale and legal situations are different. Whilst children's experiences of intra-European migration are not thoroughly researched, their experiences of being ‘left behind’ are even less understood.

The growing number of children left behind with substitute carers as a result of parental migration, and the concentration of this phenomenon in particular neighbourhoods, towns and countries, raises new social issues, namely: family fragmentation and possibilities of high-risk behaviours amongst left-behind children (see Zentgraf and Stoltz Chinchilla Citation2012, 347). Dreby and Atkins (Citation2012) explain the possible negative consequences of international parental migration for left-behind children, arguing that it can be a source of tension for children as it intensifies their engagement in family obligation across borders. Experiencing family separation as a result of migration, and subsequently living family life across borders can mean that children encounter emotional, social, educational and/or psychological difficulties (Coe et al. Citation2011; Gianelli and Mangiavacchi Citation2010; NíLaoire et al. Citation2011). There is a need for more in-depth study on the ways in which children may be involved in migration decision-making in their families, the processes of family separation they experience and the ways in which they manage their transnational lives. We use a three-fold model to analyse children's migration experiences: (1) children who move with parent(s); (2) children who move after a delay; and (3) children who never move at all but whose parents/siblings moved. The paper focuses on the experiences of migrant children (1 and 2) but those ‘left behind’ in migrant families (3) have a silent presence in this study. Children in Group 1 often experienced separation from close family members (e.g. grandparents) and friends, although sometimes they moved with one parent and therefore experienced separation from the other. Children in Group 2 experienced separation from one or both parents and/or siblings until they migrated themselves. Many children, who moved, experienced both separation and migration at the same time, having close family members and friends left behind in the home country. In our discussion we compare the findings of two qualitative studies focused on the experiences of children in intra-EU migrant worker families in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland, having first considered recent developments in research on migrant worker family migration in Europe.

Migrant worker families in Europe

In 2004, in an action that paralleled the actions of Sweden, the United Kingdom and Ireland did not place restrictions on migration from countries that acceded to the EU that year. This opened up the possibility of migration to the United Kingdom and Ireland (without the requirement of work permits) for the populations of 10 new EU countries, many of which are in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), namely: Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. Between 2004 and 2007, the largest inflows of migrants to the United Kingdom, including Scotland, and Ireland from these accession countries were from Poland. Children from Poland and other European countries made up a sizable proportion of migrants to Scotland and Ireland (see, e.g. the data from the Scottish Government, Pupil Census – Supplementary Data Citation2012) and from the national census 2011 in Ireland (Central Statistics Office – CSO 2012). Their number has increased by about 1000 every year since 2004. There were over 8000 Polish children in Scottish schools in 2012 and almost 14,500 Polish children living in Ireland at the time of the census in 2011.

Despite these numbers, however, research of children's experiences of intra-EU migration is only just beginning to emerge and it is still quite limited in scope and extent. Instead, more work has focused on family relationships during processes of migration and mobility from CEE to the United Kingdom, and these studies often do not include children as research participants. For example, Ryan and Sales (Citation2011) discuss the experiences of Polish children in London schools in the context of family migration strategies, arguing that the changing needs of children, and particularly the stage they have reached in their education, are a key element in the process of parental migration decision-making. Another example is White's (Citation2011) research on family migration strategies of Polish migrant worker families in the UK in which she raises the issue of ‘children left behind’ in Poland, but not from children's own perspectives. The works of Ryan et al. (Citation2009) and Ryan (Citation2011) also examine the lives of Polish transnational families in London but are not children-inclusive, and the research of Lopez Rodriguez (Citation2010) explores Polish migrant mothers and parenting in the UK.

Additional work on intra-EU migrant worker families has explored their transnational ties. D'Angelo and Ryan (Citation2011) suggest that some migrants, especially transient groups, may invest more time and energy in maintaining links with their country of origin, or with ethnic-specific communities in the host society, rather than establish new and ethnically diverse relationships. Adams and Shambleau (Citation2006, 88) demonstrate, however, that migrant parents with children may measure ‘success’ in the new society in terms of how well the child is doing in school, learning the new language and making new friends. Lopez Rodriguez (Citation2010) shows that some migrant parents push their children to succeed at school to overcome their own sense of stigmatisation in their new societies. Parental satisfaction with migration usually brings a higher quality of care and higher child psychosocial functioning and academic achievement, argues Robila (Citation2011). She also found in her study that Romanian migrant parents who experience higher financial stress are less responsive to and supportive of their children. These studies of intra-EU migrant worker families highlight the roles children's have and/or are ascribed in processes of family migration.

What the small body of research focused on children's experiences of intra-EU migration as part of migrant worker families suggests is that there are multiple ways in which children manage and cope with processes of intra-EU family migration (see Darmody, Tyrrell, and Song Citation2011; Devine Citation2011; Moskal Citation2015; NíLaoire et al. Citation2009, Citation2011; Sime, Fox, and Pietka Citation2010). Sime, Fox, and Pietka (Citation2010) point out that families’ socio-economic circumstances after migration, neighbourhood characteristics and children's resilience and ability to cope well with their new circumstances are major factors affecting children's experiences. In their study, they noticed considerable variation in children experiences of migration although they state that the majority of the children in their study ‘adapted well’ to their new life. None of these studies have focused on family separation during processes of family migration specifically, as we do in the following sections of this paper. With an increasing trend of employment mobility in and across European countries (Favell Citation2008; Williams and Baláž Citation2008), family separation resulting from migration is becoming a more regular feature of children's lives than is currently acknowledged.

Research design

The data that are analysed and discussed in this paper were gathered as part of two studies on intra-EU migration that were conducted independently. One study, carried out by Marta Moskal, focused on Polish migrant worker families in Scotland, United Kingdom; the other study, carried out by Naomi Tyrrell focused on migrant worker families who had migrated to the Ireland from Central and Eastern European countries, the majority of whom originated from Poland. The common aims of the studies were to explore children's experiences of migration from CEE to Scotland or Ireland and to understand how migration impacts children's everyday lives (with a focus on familial, social and educational structures).Footnote1 Many of the children across both studies had experienced family separation as a result of migration. This was usually temporary for children, ranging in time from a few months to three years.

The data from the Scotland study that are discussed in this article were collected between 2008 and 2010 during fieldwork with 65 members of Polish migrant families in Scotland (41 children and 24 adults). The families had varied backgrounds and types of settlement, that is, those living in the urban areas of Aberdeen and Edinburgh (41), the suburban areas of North Lanarkshire (13) and the rural Highlands (11). The families were accessed through schools in Scotland that are attended by a substantial number of Polish migrant children. Interviews were conducted with migrant children and parents in their homes and in schools, after classroom hours. All the interviews with family members were conducted in the Polish language, then transcribed and translated into English. In the majority of families, children and parents did not come to Scotland at the same time but were later reunited in Scotland after an extended period of separation. Among the 30 families who participated in the study, in 28 cases family members – children and parent(s) – did not migrate together. In some families, older children or other family members remained in Poland.

The Ireland study was carried out between 2006 and 2009 and focused on a broader range of European nationalities than the Scotland study did, but only the findings on Polish migrant worker families are included in this paper, for comparative purposes. Seventy-four children in total from Central and Eastern European countries who had migrated to Ireland between 2004 and 2008 participated in the study, 51 of whom were from Poland; 13 interviews were conducted with parents of some of the participating children. The majority of parents interviewed were from Poland. The children whose experiences are examined in this paper lived in urban locations in Dublin and Cork, or in adjacent suburbs. Unlike the Scotland study, in the Ireland study data gathering with Polish children did not always take place in children's homes and schools. A youth club, a parent–toddler group and cafés were additional research sites. With the exception of a pilot study, the researcher visited children in these sites over a period of several months. This enabled a rapport to be established and for children to feel comfortable (or not on some occasions) in engaging with the different methods on their own terms. Interviews and discussions between the researcher and children took place in EnglishFootnote2 although children often communicated in Polish with each other in group activities or when carrying out individual tasks in group contexts.

Despite the differences between some aspects of the research design, the two studies provide comparable data on the experiences of children in intra-EU migrant worker families, particularly their experiences of family separation.Footnote3 A distinctive feature of both projects was to pay particular attention to the views of children (Christiansen and James Citation2000) and children's competence as research participants was recognised (Morrow Citation2008). The researchers working on the project carefully observed established practices of protecting confidentiality and appropriate guidance when interviewing children.Footnote4 All family members were given project information sheets. Informed consent to interview the children was given by parents and children provided their oral and/or written assent. Children were free to discontinue the interviews and activities at any point. Both of the studies were children-inclusive and a children-centred approach was employed in (see van Blerk and Ansell Citation2007; Flutter and Rudduck Citation2004; James, Jenks, and Prout Citation1998; James and Prout Citation1990; Macbeath et al. Citation2003). This involved spending time with the children and communicating in ways in which we hoped they would feel comfortable, for example: drawing pictures, mental maps, social networks, life journeys or through storytelling (Moskal Citation2010; NíLaoire et al. Citation2011; Orellana Citation2001).

In both studies we asked the children to discuss their drawings/creations with us, basing our analyses of their experiences on their own interpretations. We anticipated that these types of methods, combined with more traditional interviewing in some cases,Footnote5 would assist our understanding of their migration experiences. By employing a suite of methods (White and Bushin Citation2011) we were able to explore children's perspectives on migration, transnational relations and wellbeing; we gained access to their life stories which illuminated the resources possessed by family members and the ways in which they were exchanged, transferred and received in their new contexts. The studies were conducted using a grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967) designed to help researchers elicit and analyse qualitative data to identify important categories in the material with the aim of generating ideas and concepts ‘grounded’ in the data. This approach is particularly appropriate for research in areas that are under-theorised (Bruck Citation2005). The research questions were open-ended and exploratory with themes emerging from the children's accounts and descriptions of their drawing/creations and activities.

Migration decision-making in EU migrant worker families

Accession to the EU has brought many employment opportunities and free movement for the people of Poland and other new EU countries. An issue that is often overlooked in discussions of intra-EU migration is the positioning of children in family migration decision-making and how this may differ according to the processes of migration these families undertake. While in public discourse about economic migration it is often assumed that parents are trying to improve the financial situation of their families, and thus are prepared to ‘pay the price’ of separation from their children and/or spouse, children's involvement in migration decision-making and their experiences of family migration processes have been overlooked (for further discussion of children's involvement in migration decision-making in different contexts see Ackers and Stalford Citation2004; Bushin Citation2009; Pantea Citation2011). This reflects the broader positioning of children within much research on family migration until recently (White et al. Citation2011) and the lack of acknowledgement that children may participate in making migration decisions in some circumstances (Bushin Citation2009). A negative aspect that sometimes follows children's lack of involvement in decision- making is that children find hard to understand the choices of their parents, especially if they are very young (Bonizzoni Citation2009).

The findings of our two studies support the assertion that children may have little agency in making migration decisions in intra-EU migrant worker families (see D'Angelo and Ryan Citation2011). Some of the children in both studies were encouraged to engage in family migration decision-making but usually this was within a restricted framework of choices outlined by parents. The majority of children did not feel that they had been active decision-makers in their families, regardless of whether they themselves were migrating, or staying in their country of origin and experiencing a period of separation from one or both parents who migrated. For example, Adam (male, age nine, Scotland study) disclosed that his parents said: ‘Bring your things and we'll take the flight.’ That was the first he knew of their decision for the family to migrate to Scotland. Jasia (female, age 15, Ireland study) experienced similar limitations on her agency within her family, explaining that: ‘My Mum said I was just coming [to Ireland] for a summer holiday, for one month. And then she said I had to stay. And I said ‘No way!’’. She explained that she felt that living in Ireland was now ‘okay’ but that she had been very upset initially when her mother told her she was staying in Ireland.

Similar to Jasia and Adam, the majority of the children in both studies did not have a choice whether or not to migrate; their parents made the decision for them. Partly this reflects the ways in which the intergenerational relationships and styles of parenting within these families are constructed; however, it is also important to consider the migratory contexts of these families. For example, rather than simply construing parents as dismissive of the impacts of migration or separation on children, or as being deceptive, not including children in the decision to migrate somewhat reflects the fluidity and precarity of many EU migrant worker families. As Jasia's case indicates, free movement within the EU enables individuals and families to migrate for short periods to look for employment that may or may not transpose into more permanent employment. Jasia's mother decided that they should migrate to Ireland as a family, rather than Jasia staying with relatives or friends in Poland, as was the case for other young people in the two studies.

Despite the majority of young people having little agency in family migration decision-making processes, parents often mentioned what they perceived to be advantageous educational and employment opportunities for children as a key reason for their family's migration (see also Moskal Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Sime, Fox, and Pietka Citation2010). Therefore parents felt that they were acting in their children's best interests through the act of migration even though they did not encourage or permit children to be active migration decision-makers. Many of the children said that were unsure what the future held for them in relation to education, employment and residential locations but some of them did appreciate their parents’ views and decisions if they took a longitudinal perspective. For example, some children viewed their migration as presenting opportunities, particularly for developing their English language skills, and they also felt that they would have more choice about their migratory pathways in the future. For example, Philip (male, age 15, Ireland study) said that his parents, particularly his mother, were keen to remain living in Ireland but they had retained a property in their home city in Poland in case his father had to return to work there. Philip and his family were very aware of the precarious nature of their existence in Ireland, as they were dependent on his father being able to retain his employment. With conjecture over the state of the Irish economy and what the future held for Ireland, Philip and his family were mindful that they needed to have a plan for the future; one that would provide for their financial needs and could involve another migration.

Processes of step-migration and separation in intra-EU migrant worker families

Much of the research in Europe on transnational families has focused on those from outside the EU (Bryceon and Vuorela Citation2002). Intra-EU migrant worker families are often overlooked in discussions of transnational migration, with an emphasis often placed on single migrant workers. However, children and parents who experience family separation are now frequent participants in intra-EU mobility; it is only very recently that there has been some exploration of these families’ step-migrations, separations and transnational living arrangements (see Robila Citation2011; Ryan and Sales Citation2011; White Citation2011).Transnational family patterns characterise new arrivals from Poland who have settled and work in Scotland and Ireland. Polish migrants in both these countries often are transnational, with family members living across different nation states. These migratory flows are very often circular sometimes resulting in step-migration; return migration and/or frequent movements of the parent(s) and/or children between ‘home’ and ‘host’ countries (Vertovec Citation2008). The notion of step-migration that we use here implies spatial relocations by steps or stages from a migrant's origin to a destination (Conway Citation1980). These migrations and movements often entail family separation of various kinds: parent(s) separated from children, parents separated from each other (in two parent families), siblings separated from each other, children and/or parents separated from extended family members (e.g. grandparents).

Unlike the experiences of families in situations of forced migration, parents in both of our studies had decided that family separation was a possible and manageable part of their family migration process. All of the research participants then had been involved in some kind of family reunion in Scotland or Ireland. Although family separation prompted by migration was temporary for all of the children in our two studies, it did mean that children had to contend with physical dislocation from their former places of residence at the same time as being apart from one or more family members. We can consider this to be a transitional period in the migrations of these children but one that highlights the complexities of family migration processes, the negotiations that occur between family members, and the potential impacts on children. Many participating children have also experienced separation at the time of their own migration, leaving grandparents, uncles, cousins and other close relatives and friends behind. Extended family plays a central role in social structure in Poland. Most of the migrant children seemed to be socialised into that aspect of Polish culture, learning to form the individual social network (inner circle) of extended family members.

As Polish migrants have become more settled in the United Kingdom and Ireland, family reunion has become more common (see Lopez Rodriguez Citation2010; Ryan and Sales Citation2011; Ryan et al. Citation2009; White Citation2011). Step-migration seems to be the usual pattern for contemporary Polish family migration in the EU. Lopez Rodriguez (Citation2010) suggests that the mother sometimes follows with the children if they are young, or often migrates by herself, leaving them behind with grandparents or relatives.

In our research we have found various models of family separation and reunion. In some cases reunion is a planned strategy from the outset, with one or both parents migrating and sending for children once they have secured employment and a place to live. Children live with family members or friends in the place of origin (sometimes requiring an internal migration rather than staying in exactly the same residential location) until this time. In other cases, the family may not have intended a reunion, but after a period of separation (sometimes several years) parents decided that the remaining partner and children would follow the lead migrant to the country of destination (i.e. Scotland or Ireland), for emotional and/or financial reasons. The majority of the studied families have been involved in family reunion after a period of separation. There were still some older children (aged 16+) ‘left-behind’ by migrant parent(s) and younger sibling(s).

In contrast to other studies focused on migrant children and their families (e.g. Sime, Fox, and Pietka Citation2010), the socioeconomic situation of the parents was not always the paramount factor influencing families’ migration processes and living arrangements. In the debate on the cost of family separation, some argue that the negative effects of family separation are often hidden from the migrant parents, who make the decisions, and can be only tracked over time (Zentgraf and Stoltz Chinchilla Citation2012). For some families, being and doing family in the same residential location was more important than economic impacts (see White Citation2011). Similar to White's (Citation2011) study, some of the parents in our studies were not prepared to tolerate prolonged separation from children and/or other family members as part of their migration process. Ryan et al. (Citation2009) reminds us that family migration does not refer only to nuclear families and may in fact involve a wide range of relatives, and several of the migrant families in our studies comprised children, parents and grandparents who had participated in step-migration at various times. We also found examples where migrating parent(s), left children behind with relatives in Poland.

Children's experiences of step-migration and family separation

In our studies, children's experiences of step-migration and family separation varied, sometimes according to age and gender, as did their coping strategies. The difficulties that children had in adjusting to temporary family separation were frequently mentioned by children and parents, with younger children in particular seeming to find it difficult to understand why their family had separated, albeit temporarily. In contrast to Sime, Fox, and Pietka (Citation2010), younger children in our studies did not seem to be more adaptable to their new contexts than older children and expressed a lack of understanding. Our results confirm Kirova's (Citation2010) observation that for the younger children, it is frequently assumed they want what their parents want, and even if they express disagreement, they are expected to obey their parents. For example, Eva's six-year-old son (Scotland study) said that he would like to go back to Poland, to his home. The mother was rather surprised by his response but did not attach any significance to his will. She explained that they moved permanently abroad and there is no chance to go back.

Many of the older children in our studies said that they had found family separation ‘difficult', ‘hard to get used to', or ‘weird', particularly in the short-term. For example, Vicky (female, age 11, Scotland study) wanted to come to Scotland: ‘I missed my dad [when he lived in Scotland and she lived in Poland], he was at home maybe once a year. I do not want to come back to Poland now’. Her brother (age nine) was not happy to be in Scotland, however, as he had left his friends behind in Poland and had not made very many friends in his new location. He said that he did not like his new school and spent a lot of time alone, using his computer. His mother described his behaviour as ‘troublesome’, and seemed to overlook his feelings towards migration and living in Scotland.

The lack of input into family migration decision-making, as well as not knowing what to expect in their migration destinations, added to the difficulties some children experienced in adjusting to their new residential locations. In addition, the feeling that people and places ‘back home’ were changing while they were not there was unsettling for some children. In both studies, children commented on the difficulty of making new friends and some made the distinction between having friends and just knowing people or having colleagues. For example, Monica (female, age 10, Scotland study) said, ‘I do not have friends here, but I have colleagues at school. In Poland I have friends but maybe I do not have them anymore'. Children often made references to, and comparisons with, their previous situations in Poland or imagined how it would be to be in Poland. Paula (female, age 16, Scotland study) said, ‘I draw a home, in Poland, not a real one but a home I dream about, spacious, for the future'.

Some of the children's narratives and drawings suggested that they viewed migration as something that moved them away from their friends and other members of their family, which sometimes put them in a situation of isolation and loneliness. For example, Nancy (female, age 15, Scotland study) said: ‘When my parents go to work now I have to stay alone sometimes. In Poland, there was always somebody around, my granny or granddad or my uncles or somebody I know well’. Children often mentioned going shopping as ‘something to do’ in their new locations, sometimes commenting on the Polish products they could purchase, and comparing shopping at ‘home’ with Scotland or Ireland. For example, Adam (male, age nine, Scotland study) said: ‘I go frequently here to the shop “Asda” and I buy things to not be bored. In Poland I would have more friends but I could not buy things because they are too expensive'.

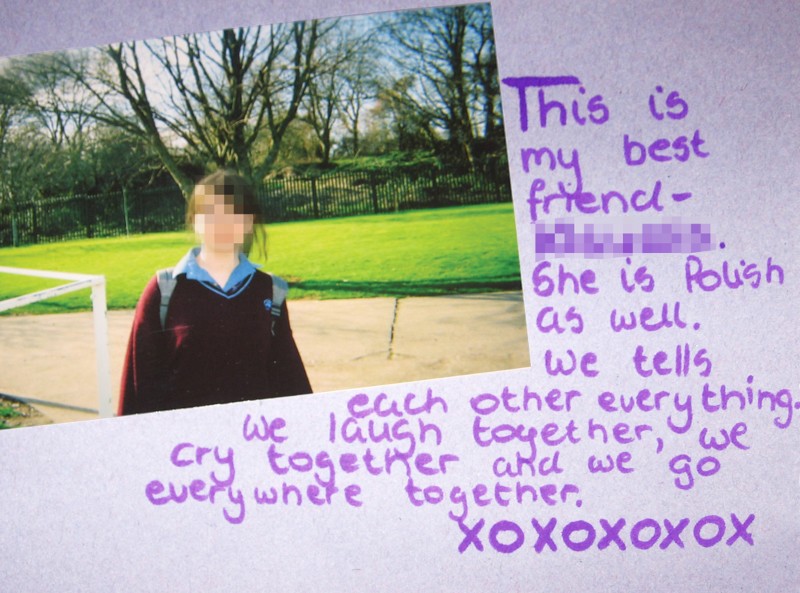

Maintaining social and emotional connections with family and friends in their home countries, whilst managing to make connections with new people and places in the migration destinations, seemed to be the most effective strategy for children who said that they felt happy with their current situations and circumstances. Transnational identity formation is an important process for these young migrants and not just of concern to adults as is often implied in the literature. In the Scotland study Molly, age 15, drew a very elaborate tree of attachments (see ) and then explained during the interview that she drew a hierarchy of things that were important to her in Poland and in Scotland. Her drawing shows her dislocation from her friends and connections in her home country, but also her maintaining these connections whilst simultaneously forging new ones in her migration destination. ‘Under my tree I placed my friends, my football team and my best friend in Poland. These people I put on a par with my family'. Devine (Citation2009, 524) describes how children ‘talked about their cultural worlds, feeling “at home” and “different” in both places’. This was a common experience for the children in our studies, which they reflected on, perhaps best described as living within two worlds. Coping with separation from family members seemed to be easier if children had been able to forge new friendships in their migration destinations. However, children also reflected on these friendships and compared them to friendships ‘back home’. For example, when living in Poland, Sally (age 14, Ireland study) had been used to socialising with her friends on weekends and visiting their houses but this was not common for her in Ireland. In her photo-book (see ) she said that she had one best friend, who had also migrated from Poland, and when interviewed she said she had very few Irish friends. Similar to the children in D'Angelo and Ryan's (Citation2011) study, our respondents said that they found it much easier to make friends with children from their own national or ethnic groups and/or children with other migrant backgrounds.

Figure 1. A drawing by Molly: Text from the top: important people; football teammates in Poland; family; friends in Poland; the best girl friend and boy friend in Poland; friends in Edinburgh; trainee in Poland; football mates in Edinburgh; friends form school; football is very important for me.

It was common for children in both studies to be separated from siblings during processes of family migration. This resulted from one or both parents migrating to Scotland or Ireland with one or more of their children, leaving one or more children in the home country to be cared for by parents, relatives or family friends. For example, Mauva (female, aged 17, Ireland study) said:

I was 16 then [when her mother and sister moved to Ireland] but I lived with grandmother [in Poland] and we argued all the time. Then I decided I wanted to move here [Ireland] because of [arguing with] my grandmother and because of my English and my school. Two years [apart from my mother and sister] is too much for me. My relations with my sister and my Mum are very good, I think.

Has that changed since you moved?

It was always very strong but now … but because my mother works less and my own motivation, it's better. I spend more time with my Mum.

The children often had the love and care of their extended family, which assumes some parental responsibilities when the parent(s) are away or working, whether the children live in the ‘home’ or the ‘host’ country. These examples bring attention to the more positive side of transnational family life, showing family resilience, the benefits of extended family networks, and the ways in which such adaptive strategies enable emotional and financial support for different family members during times of migration. Indeed, sometimes it seems that geographical distance is not necessarily a barrier to being a close family, and participants stressed the importance of transnational links, the ‘tightness’ of the emotional bonds, and the level of trust expected and experienced between family members. It is important to point out, however, that EU citizens are enabled to maintain transnational ties and reunite their families in ways that migrants from other backgrounds are not (Bushin and White Citation2010; Ryan Citation2011). Despite the distances involved in their family separations, children were very often able to meet up with their family members (siblings or parents) once or twice a year. The children commented on their ability to use cheap flights and to communicate regularly via the Internet.

Living transnational family lives

For both children and parents, relatives and/or friends in Poland frequently provided an important source of emotional support through telephone/internet chats and emails. Ryan et al. (Citation2009) argue, after Granovetter (Citation1973), that emotional support may be provided through a close, intimate and long-standing relationship with someone who lives outside one's immediate physical environment. New communication technologies have enabled migrants to maintain these transnational emotional ties through regular and affordable communication (Panagakos and Horst Citation2006). In our studies, migrant children appropriated communication technologies very quickly and used them to communicate with family and friends ‘back home'. Vicky (female, age 10, Scotland study) said to describe her drawing:

I drew the phone to call my family in Poland and a computer to talk to them and the family here: my mum, dad and sister and in Poland; my grand mum and granddad and cousins and my uncles, aunts and friends.

In these families, as others have shown (see Olwig Citation1999), children serve as social, emotional and economic links for households that span transnational borders. Parents also may sustain ties ‘back home’ because their children ask for, or seek out, such connections. Retaining connections with family and friends back home in their country of origin through the use of transnational communication technologies became an important aspect of the children's life as they usually did not have the means to visit their home country as frequently as they wished to.

Maintaining transnational connections in some migrant families allows them to provide not only emotional support from a distance but also practical support, including various forms of childcare. For example, Robert's (age 11) mother reported,

My parents looked after both of my sons. After three years, my younger son came to join me. He misses my parents very much. They help us a lot, they come over once a year, they came for two months last year.

We arrived here in succession, first my son, then my husband, followed by me with the grandson, and a month later my daughter with her younger child. We are here all together and we (me and my husband) live with our [divorced] daughter and the grandchildren in one flat. I take care of the children and bring them to school and back, do homework with them. I use to go for meetings to the school. My daughter went only once, she works a lot, and she doesn't have a time.

Conclusion

In this article we have focused on the migration decisions, migratory processes and experiences of intra-EU migrant worker families who recently migrated from Poland to Scotland and Ireland. We have analysed children's experiences in particular, contributing to overcoming the lack of research on transnational intra-EU family migration that seeks to include children's voices. By considering family migration to be a process or set of varying processes rather than a singular event (after Halfacree and Boyle Citation1993), the nuances of intra-EU family migration decision-making, step-migration and separation can be revealed. Ryan (Citation2011) suggests that migrant families that experience family step-migration and family separation may not be participating in a new migrant lifestyle but rather a phase in the migration trajectory. This holds true for the families discussed in this paper, with family separation usually being considered as a necessary and sometimes unavoidable part of migratory processes. The open-ended orientations of many of the families allows diverse future scenarios, including children going back independently to study or work in the home country, children migrating to other countries, parents returning to the home country after retirement, for example.

For all of the children whose experiences have been highlighted in this paper, coping with family separation at the same time as family migration presented challenges that had differential impacts. The studies show that many migrant children seemed to function well despite periods of separation from parents and/or other family members. However, the emotional repercussions of migration should not be downplayed as they are an important aspect of transnational life and children can experience difficulties in making new friends and coping without siblings and/or parents. Our data suggest that children can play important roles within intra-EU migrant families by contributing towards keeping families emotionally connected across international borders, by using transnational technologies, for example.

The evidence provided in the paper points to children's lack of agency in family migration decision-making, to the difficulties they may experience in relation to both separation and migration, and a certain acceptance of more long-term benefits. In contrast to some studies (e.g. Sime, Fox, and Pietka Citation2010) that observe that economic factors are the overriding consideration in family migration strategies, our studies illustrate cases in which families reunite even though it is less ‘cost-effective’ than maintaining a family back in Poland. Our studies confirm White's (Citation2011) argument that emotional reasons can prevail over apparent economic rationality. As the phenomenon of parents, often from CEE, temporarily leaving their children to find work in other European countries is relatively new, the long-term effects on children, parents and wider society are not yet fully understood. However, given the likelihood of increased family migration and family separation across Europe in future years, there is a need for further research to fully explore the impact of migration on the relationships children have with their families. In particular, we suggest that new cross-cultural comparative and longitudinal studies will be crucial to understanding the impacts of children's experiences of family step-migration and separation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Each study had additional aims (see Moskal Citation2014a; Tyrell et al. Citation2012).

2. We recognise that this is a limitation of the study. However, the researcher is not Irish and her migrant background was often commented on as a point of commonality by the children, leading them to discuss aspects of living in Ireland that they sometimes said they would not have been happy to mention to an Irish researcher.

3. The researchers realised these data synergies when participating in a conference on children and migration in 2011.

4. Institutional ethical protocols were followed in both studies. The paper does not use the children's real names. The names of children used are pseudonyms.

5. The methods employed depended on a number of factors: children's choice, children's age and understanding, the research location, group or individual activity.

References

- Ackers, L., and H. Stalford. 2004. A Community for Children? Children, Citizenship and Internal Migration in the EU. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Adams, L. D., and K. M. Shambleau. 2006. “Teachers', Children's and Parents' Perspectives on Newly Arrived Children's Adjustment to Elementary School.” In Global Migration and Education: Schools, Children and Families, edited by L. D. Adams and A. Kirova, 87–102. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associetes.

- van Blerk, L., and N. Ansell. 2007. “Participatory Feedback and Dissemination with and for Children: Reflections from Research with Young Migrants in Southern Africa.” Geographies 5 (3): 313–324.

- Bonizzoni, P. 2009. “Living Together Again: Families Surviving Italian Immigration Policies.” International Review of Sociology: Revue Internationale de Sociologie 19 (1): 83–101. doi: 10.1080/03906700802613954

- Bruck, C. 2005. “Comparing Qualitative Research Methodologies for Systemic Research: The use of Grounded Theory, Discourse Analysis and Narrative Analysis.” Journal of Family Therapy 27: 237–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2005.00314.x

- Bryceon, D., and U. Vuorela, eds. 2002. Transnational Families. Oxford: Berg.

- Bushin, N. 2009. “Researching Family Migration Decision-Making: A Children-in-Families Approach.” Population, Space and Place 15: 429–443. doi: 10.1002/psp.522

- Bushin, N., and A. White. 2010. “Migration Politics in Ireland: Exploring the Impacts on Young People's Geographies.” Area 42 (2): 170–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00904.x

- Christiansen, P., and A. James, eds. 2000. Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices. London: Falmer Press.

- Coe, C., R. Reynolds, D. Boehm, J. M. Hess, and H. Rae-Espinoza. 2011. Everyday Ruptures: Children, Youth and Migration in Global Perspective. Nashville: Vanderbilt.

- Conway, D. 1980. “Step-Wise Migration: Toward a Clarification of the Mechanism.” International Migration Review 14 (1): 3–14. doi: 10.2307/2545058

- D'Angelo, A., and L. Ryan. 2011. Sites of Socialisation – Polish Parents and Children in London School, Studia Migracyjne – PrzeglądPolonijny, Special Issue Garapich, M.P. (ed.) PolacynaWyspach (w WielkiejBrytanii), 1.

- Darmody, M., N. Tyrrell, and S. Song. 2011. The Changing Faces of Ireland: Exploring the Lives of Immigrant Children and Young People. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Devine, D. 2009. “Mobilising Capitals? Migrant Children’s Negotiation of their Everyday Lives in School.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 30: 521–535. doi: 10.1080/01425690903101023

- Devine, D. 2011. Making a Difference? Immigration and Schooling in Ireland. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Dreby, J., and T. Adkins. 2012. “The Strength of Family Ties: How US Migration Shapes Children's Ideas of Family.” Childhood 19 (2): 169–187. doi: 10.1177/0907568211411206

- Favell, A. 2008. Eurostars and Eurocities: Free Movement and Mobility in an Integrating Europe. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Flutter, J., and J. Rudduck. 2004. Consulting Pupils: What's in it for Schools? London: Routledge-Falmer.

- Gianelli, G., and L. Mangiavacchi. 2010. “Children's Schooling and Parental Migration: Empirical Evidence on the ‘Left-Behind’ Generation in Albania.” Labour 24: 76–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9914.2010.00504.x

- Glaser, B. G., and A. C. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Granovetter, M. 1973. The Strength of Weak Ties, Reprinted in Scott, J. (ed.). 2002. Social Networks, 60–80. New York: Routledge.

- Halfacree, K., and P. Boyle. 1993. “The Challenge Facing Migration Research: The Case for a Biographical Approach.” Progress in Human Geography 17: 333–348. doi: 10.1177/030913259301700303

- James, A., C. Jenks, and A. Prout.1998. Theorising Childhood. Oxford: Polity.

- James, A., and A. Prout.1990. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood. London: Falmer.

- Kirova, A. 2010. “Moving Childhoods: Young Children's Lived Experiences of being Between Languages and Cultures.” In Global Migration and Education.School, Children and Families, edited by L. D. Adams and A. Kirova, 185–198. London: Rutledge.

- Lopez Rodriguez, M. 2010. “Migration and a Quest for ‘normalcy’. Polish Migrant Mothers and the Capitalization of Meritocratic Opportunities in the UK.” Social Identities 16 (3): 339–358. doi: 10.1080/13504630.2010.482422

- Macbeath, J., H. Demetriou, J. Rudduck, and K. Myers. 2003. Consulting Pupils – A Toolkit for Teachers. Cambridge: Pearson.

- Morrow, V. 2008. “Ethical Dilemmas in Research with Children and Young People about their Social Environments.” Children's Geographies 6 (1): 49–61. doi: 10.1080/14733280701791918

- Moskal, M. 2010. “Visual Methods in Researching Migrant Children Experiences of Belonging.” Migration Letters 7 (1): 17–32.

- Moskal, M. 2014a. “Language and Cultural Capital in School Experience of Polish Children in Scotland.” Race, Ethnicity, Education. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13613324.2014.911167.

- Moskal, M. 2014b. “Polish Migrant Youth in Scottish Schools: Conflicted Identity and Family Capital.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (2): 279–291. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2013.815705

- Moskal, M. 2015. “‘When I think Home I think Family here and there’: Translocal and Social Ideas of Home in Narratives of Migrant Children and Young People.” Geoforum 58: 143–152. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.011.

- Ní Laoire, C., N. Bushin, F. Carpena-Mendez, and A. White. 2009. Tell me about Yourself: Migrant Children's Experiences of Moving to and Living in Ireland. Cork: UCC.

- Ní Laoire, C., F. Carpena-Mendez, N. Tyrrell, and A. White. 2011. Childhood and Migration in Europe: Portraits of Mobility, Identity and Belonging in Contemporary Ireland. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Olwig, K. F. 1999. “Narratives of the Children Left Behind: Home and Identity in Globalised Caribbean Families.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 25 (2): 267–284. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.1999.9976685

- Orellana, M. 2001. “The Work Kids Do: Mexican and Central American Immigrant Children's Contributions to Households, Schools and Community in California.” Harvard Educational Review 71 (3): 366–390. doi: 10.17763/haer.71.3.52320g7n21922hw4

- Panagakos, A. N., and H. A. Horst. 2006. “Return to Cyberia: Technology and the Social Worlds of Transnational Migrants.” Global Networks 6 (2): 109–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2006.00136.x

- Pantea, M. 2011. “Young People's Perspectives on Changing Families' Dynamics of Power in the Context of Parental Migration.” Young 19 (4): 375–395. doi: 10.1177/110330881101900402

- Parreñas, R. S. 2005. Children of Global Migration: Transnational Families and Gendered Woes. Standford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Pratt, G. 2009. “Circulating Sadness: Witnessing Filipina Mothers’ Stories of Family Separation.” Gender Placeand Culture 16 (1): 3–22. doi: 10.1080/09663690802574753

- Robila, M. 2011. “Parental Migration and Children's Outcomes in Romania.”Journal of Child and Family Studies 20 (3): 326–333. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9396-1

- Ryan, L. 2011. “Transnational Relations: Family Migration among Recent Polish Migrants in London.” International Migration 49 (2): 80–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00618.x

- Ryan, L., and R. Sales. 2011. “Family Migration: The Role of Children and Education in Family Decision-Making Strategies of Polish Migrants in London.” International Migration. Advance online publication. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00652.

- Ryan, L., R. Sales, M. Tilki, and B. Siara. 2009. “Family Strategies and Transnational Migration: Recent Polish Migrants in London.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (10): 61–77. doi: 10.1080/13691830802489176

- Scottish Government, Pupil Census, Supplementary Data. 2012. Online document on www.scotland.gov.uk.

- Sime, D., R. Fox, and E. Pietka. 2010. “At Home Abroad: The Life Experiences of Eastern European Migrant Children in Scotland.” ESRC Report. Glasgow: University of Strathclyde.

- Spicer, N. 2008. “Places of Exclusion and Inclusion: Asylum-Seeker and Refugee Experiences of Neighbourhoods in the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (3): 491–510. doi: 10.1080/13691830701880350

- Szilassy, E., and Z. Arendas. 2007. “Understandings of ‘Difference’ in the Speech of Teachers Dealing with Refugee Children in Hungary.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (3): 397–418. doi: 10.1080/13691830701234525

- Tyrrell, N., A. White, C. Ní Laoire, F. Carpena-Mendez, eds. 2012. Transnational Migration and Childhood. London: Routledge.

- Vertovec, S. 2008. “Circular Migration: The Way Forward in Global Policy?” Canadian Diversity 6 (3): 36–40.

- White, Anne. 2011. Polish Families and Migration Since EU Accession. Bristol: Policy.

- White, Allen and N. Bushin. 2011. “More-Than-Methods: Learning from Research with Children in the Irish Asylum System.” Population, Space and Place 17 (4): 326–337. doi: 10.1002/psp.602

- White, Allen, C. Ní Laoire, N. Tyrrell, and F. Carpena-Méndez. 2011. “Children's Roles in Transnational Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (8): 1159–1170. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2011.590635

- Williams, A. M., and V. Baláž. 2008. International Migration and Knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Zentgraf, K. M., and N. Stoltz Chinchilla.2012. “Transnational Family Separation: A Framework for Analysis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (2): 345–366. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2011.646431