ABSTRACT

Models relating to the participation of children are often explicitly aimed at facilitating or evaluating participation in decision-making processes on local levels. However, these models often build on hierarchically ordered ‘ladders’ of children’s involvement starting with passive involvement and increasing gradually to highly active engagement. Such models become problematic when designing or evaluating participative activities for young children. On the basis of two ethnographic studies conducted in children’s libraries, we propose an alternative model based on a view of participation as processual rather than definitive. Theoretically, the paper draws mainly on human rights theory as well as on theories and concepts derived from childhood studies such as participation and citizenship. The new model of participation demonstrates how the idea of participation can be operationalized at practical levels to include the very youngest children.

Introduction

Interest in the participation of children and young people in civic society has been gaining momentum in recent years particularly as a consequence of the Citation1989 ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). While earlier international manifestos have paid attention to children’s right to provision and protection, the CRC refers in a number of its articles to children’s rights as citizens and to participation. Sweden’s ratification of the CRC entails that it has become a requirement for all its municipalities, authorities and institutions that concern children to relate to the CRC’s guidelines. However, a research overview conducted by the Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket Citation2003) shows that young people far up in their teens have vague ideas of what their own citizenship implies and of democratic processes. It was found that many were unsure of what democracy entails and were unaware of how they could influence society. The report concludes that young people who lack a sense of citizenship are unlikely to take the opportunities that actually exist to exert influence. Such a conclusion makes it imperative to reconsider how children can be fostered to active citizenship from an early age and to involve them in participative processes.

Participation is usually viewed as a prerequisite for citizenship or as a method through which full citizenship can be achieved or as both. However, the concept itself is highly contested which leads to difficulties when institutions attempt to operationalize it in activities for children. In Sweden, institutions such as schools, public libraries and museums as well as local authorities have been struggling to find ways of allowing children to influence activities in the spirit of the CRC (Nordenfors Citation2010; Sandin Citation2011). Difficulties have been tied up with views of participation as something that concerns decision-making, and that children’s participation is an issue of the degree to which they can share in decision-making. Children’s participation has also become strongly connected to a child’s age or maturity, not least through the wording in CRC:

Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child. (CRC Citation1989, Art. 12)

The contribution and limits of earlier models of participation

Since the ratification of the CRC, participation, at least in a Swedish context, has become a buzz-word in guidelines for institutions involving children. However, the concept itself is somewhat vague and, in similarity with other popular concepts that many can agree on, its usefulness is partly dependent on this vagueness – it can be interpreted and applied in so many ways. Two of the most well-known models developed to assist public institutions in facilitating the participation of children in developing or influencing activities are those of Roger Hart (Citation1997; Citation2008) and Harry Shier (Citation2001). These models build on hierarchically ordered ‘ladders’ of children’s involvement starting with passive involvement and increasing gradually to highly active engagement. They both visualize participation in terms of the degree to which children and young people can influence a given project or activity. Hart’s ladder describes degrees of participation varying from projects where children are used as decorative symbols merely suggestive of participation to projects that are initiated by children and carried out in collaboration with adults. They are also child-focused in the sense that participation is understood as something that emerges from children themselves and is to some degree dependent on the child’s age and maturity. This suggests that it is hardly to be expected that the youngest children can decisively influence institutions that affect their own lives. However, these models should not be interpreted in the sense that that the uppermost rungs of the ladder are the ultimate goal of participative projects. Free choice and context are also important elements of the notion. Participation is not always possible or even desirable in all situations (Mcneish Citation1999).

Everyday understandings of participation include notions that it is about handing over decision-making to children. This can be associated with the idea that influence and power are quantifiable and can be ‘shared out’ between different actors i.e. that you can have, or not have, power, and if someone (a child, for example) gets more power, then someone else (an adult, for example) will have less. In accordance with Gallacher and Gallagher (Citation2008), we argue that power is something that is exercised, it permeates everything we do and it builds on interaction (Clark and Richards Citation2017; Richards, Clark, and Boggis Citation2015). What is of interest is not who ‘holds’ power but how it is exercised and negotiated, in which contexts and with what effects. The view of participation that we will develop in this article is rooted in this view of power where communication and mutual respect are essential aspects. Another problem is that attention tends to be focused on participation in terms of individuals’ freedom of choice (choosing to take part or not) rather than on participation as collective action (doing things together). In concurrence with Johannesen and Sandvik (Citation2009, 31) we take the view that participation is about ‘being part of a collective where one is respected and included regardless of opinions and attitudes’.

While Hart’s and Shier’s models are useful in the gauging of children’s active participation in organized activities, they are dependent on both children’s awareness of the idea of participation and their ability to express themselves verbally. Both models break down the notion of participation to concrete practical questions: Have children been invited to give an opinion? Are they listened to? Can they take initiatives themselves? To what degree have they been involved in decision-making processes? Implicitly however, some children are excluded on the grounds that they are too young.

Like several other researchers (Clark and Richards Citation2017; Horgan et al. Citation2016) we regard participation as an ongoing relational process carried out by individuals in their everyday lives, in play, learning and work. The notion of the autonomous individual is replaced by an understanding that everybody, not just children, are dependent and incomplete (Lee Citation2001). Specifically, Holt (Citation2013, 646) argues that it is important to consider infants, since ‘the vulnerability and relationality of infants is merely a particularly stark expression of the intersubjectivity and interdependence of all human beings’. This view envisages children, adults, place and objects in interaction and step by step driving the process further. Participation in this sense is not dependent on age, maturity or competence and seen as a relational process where nothing is defined in advance, but that the child, the adult and the place are defined during the process.

Background to the development of the model

In light of the research projects we were involved in where library staff were struggling to find ways of implementing participation for the very youngest children, the ladder models proved inadequate and led us subsequently to develop our own model on the basis of the findings of the projects mentioned earlier and which we describe briefly below.

The empirical material was generated by two ethnographic projects. The first project was focused on young children’s (0–5 years) participation in cultural activities in a municipal library. Its research objective was to follow the development of a cultural centre for preschoolers in Borås city library by seeking children’s and their caregivers’ perspectives on cultural activities and their understandings of the concept of participation. We also sought to find methods of actively working with participative processes and to relate our findings to research on childhood, participation and empowerment. The second project, which also covered three years, was similar in that the idea of participation and how it can be operationalized in library work was central. In the latter project the children’s department in Malmö city library was renovated and reorganized at the same time as the staff embarked on a course of professional development designed to allow children to influence the renovation and reorganization processes. The staff were particularly interested in finding ways of implementing the idea of participation in this development process and we were invited to follow this process (see report, Johansson and Hultgren, Citation2018).

In total, the empirical material consists of participative observations, (field notes, photographs and video sequences) of happenings, play, workshops with children and other activities; individual and focus group interviews with caregivers, library staff and politicians (Borås); and ongoing dialogue and workshops with the project staff. In the analyses of both projects we took a grounded analysis approach which entailed developing concepts and thereby constructing a model as we worked. In the following we attempt to describe this process of model-building and to illustrate its different levels and aspects with the empirical material generated by the projects.

Building a model

The model of participation consists of three interdependent levels: an ontological level, an ideological level and an implementation level. The idea is that the implementation level, where the concrete work is carried out, is grounded in an ontological and an ideological level, and that the two top levels need to be made visible and concretized. Ontology concerns worldview and human perception. The consequences of the ontological level are translated into the ideological level in the form of goals, guidelines, policies and theories. What is carried out at the third level is thereby anchored in the ontological and ideological levels. Ontologies of children can differ; children can, for example be regarded as human becomings following predetermined developmental phases or as blank sheets subject to environmental influences, or as little devils in need of discipline or, as basically unique human beings. Various policies, theories and goals guide those who work with children and who design programs and activities for participation. Starting from the implementation level, without having considered the two top levels thereby implies the risk of misunderstandings, conflicts and not achieving the expected results (c.f. Cele and van Burgt Citation2015; Gallacher and Gallagher Citation2008).

The ontological level of participation

In our case the ontological level draws strongly on human rights theory where we emphasize that ‘Children’s rights are human rights’ (Wall Citation2017). We depart from an ontology implying that human beings are constantly becoming, that we create ourselves, each other and the world around us through our preunderstandings and that we ‘become’ in communication with others. Several childhood researchers have helped us in substantiating this view, for instance Lee (Citation2001) who maintains that we are all ‘becomings’ and thus form each other. Ethicist and philosopher John Wall (Citation2017) describes the CRC as a landmark document because for the first time in international law it includes children’s rights to public participation, but he also has reservations. Although, as Wall points out, human rights theory is always evolving and responsive to societal development it has nevertheless ‘lagged behind actual children’s rights practices’ (Citation2017, 39). His critique of the CRC concerns what he sees as its adultism, i.e. that the manifesto is biased towards adults as norm. In his view, rights concerning children need to be focused less on ‘child saving’ and more on ‘child empowerment’ (Citation2017, 4). He builds a strong case for rethinking human rights to fully include and empower children and young people:

Child saving is the assumption that children’s rights exist primarily as means for children to be taken care of by adults: to be protected from various kinds of violence and harm and to be provided with various kinds of entitlements and resources. These ways in which adults take responsibility for children are certainly important. But they reduce children only to human rights objects, denying them opportunities also to act as human rights subjects.

Child empowerment, in contrast, means that children’s rights are founded on a deeper respect for children as equally important contributors to societies. Just as for adults, rights to protections and provisions do not have to exclude rights to participation. Rather, in whatever new and imaginative ways would be necessary, children need and deserve to be included as fully empowered members of the human rights community. (Wall Citation2017, 4)

Many childhood researchers have questioned the normative view of the world as composed of independent adults and dependent children (e.g. Holt Citation2013; Johansson Citation2005; Lee Citation2005; Mayall Citation2002; Moosa-Mitha Citation2005). Wall’s (Citation2017) contribution lies in the strength of the case he makes for including children in human rights theory on the basis of diversity or difference rather than maturity. Citing the feminist philosopher Ruth Lister, Wall (Citation2017, 37) argues that children have ‘the basic right to have society recognize their uniquely different lived experiences’. The implications of going beyond age as a means of differentiating between people implies developing a more fruitful ‘culture of communication’ (Christensen Citation2004) with children where adults have a particular ethical responsibility to recognize, accept and confirm children (Wall Citation2010).

Taking the standpoint that differences between people enrich and contribute to societal development by increasing our understanding of our own worlds as worlds that include others, the model we propose has a difference-focused perception of citizenship, where differences such as age, sex, origin, ability, etc. are not viewed as problems or deviations but quite the opposite – as resources in a society. Children are viewed as ‘differently equal’ but equally valuable thus acknowledging their presence and agency (Moosa-Mitha Citation2005, 386).

On the ontological level the staff in the children’s department of Malmö city library, for instance, worked with the idea of participation in a research reading circle. They read texts drawing on childhood studies as the basis for discussions of theoretical concepts in relation to their work and to the renovation of the library. In a questionnaire sent out shortly after the new children’s library was inaugurated the staff commented on the value of the reading circle to their understanding of participation:

It left a clear picture that what is required is a great deal of preparation and thinking before the work starts. We know now that everyone in the department needs to apply this way of thinking [about participation] to every single aspect when we are about to make small or big changes. Participation isn’t really about physical objects and resources, it’s s really an approach to our work. (Johansson and Hultgren Citation2018, 71)

The ideological level

The ideological level derives from the ontological level and is formulated in this case in the values of the public library. Leckie and Hopkins (Citation2002, 333) define the ideology of the public library as ‘inherently democratic, neutral, educational and inclusive’. One of the core values of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA Citation2017) is ‘the belief that people, communities and organizations need universal and equitable access to information, ideas and works of imagination for their social, educational, cultural, democratic and economic well-being’. Leckie and Hopkins (Citation2002) describe the public library as:

a spatially unrestricted communal meeting ground for all members of a pluralistic society, a shared site for people of various classes, ethnicities, religions and cultures to mingle and create the heterogeneity of open democracy. (Leckie and Hopkins Citation2002, 332)

As a result of the research reading circles in the children’s library in Malmö, the staff formulated their ideological values in a written manifesto and published it on their blog:

Children and their adults can influence our activities in different ways.

We take their views and suggestions seriously and reflect them in what we do.

Our visitors can and do leave an impression

Participation is a relationship

Participation is about listening, showing respect, inclusion and communication (Malmö Stad Citation2015)

Several aspects of participation are encompassed in this manifesto: access, influence, respect, dialogue and communication. Not least important is the view that it is not possible to determine in advance how participation will occur or what the consequences of participation might be; rather that the library undertakes to afford the participation of children and their caregivers.

The manifesto above constitutes a commitment to participation as a relational process and it takes further support from a range of sociocultural theories such as theories of play in the design of activities and space. Cultural activities for children and children’s play are not, in this perspective, viewed as a means for adults to fulfil goals beyond playing itself, for example, for reaching the learning goals of a school curriculum. Play and engagement in cultural activities are regarded as valuable in themselves. Our departure point is that what children have in common is the fact that they are young, dependent and controlled by adults. This is something they deal with in play and which helps them to expand their spheres of action. We regard it as a way of being with others, as a set of social skills involving knowing how to get others to play, how to perform play and how to use play tools such as toys and stories (Bishop and Curtis Citation2001; Corsaro Citation1985; Thomson and Philo Citation2004). In recent years theories of materiality and embodiment have enriched childhood studies (eg. Anuerin Smith and Dunkley Citation2018; Olsson Citation2009; Prout Citation2005; Skar and O’Brien Citation2016) by allowing us to understand children’s participation also in terms of embodiment, spatiality and materiality. In a view of participation as processual focus shifts from ‘being’ to ‘doing’, from a question of what a child ‘is’ to how children’s participation is ‘done’. This is closely intertwined with the affordances of a place or situation (Johansson and Hultgren Citation2015).

The formulation of an ideological level commits the libraries to sensitiveness to children’s play and ways of learning and being. One of the members of the reference group for the children’s cultural centre in Borås took the following view:

It’s about listening to what children say about the room, their experiences of the place, to play with that thought, to talk to them, to check out the smallest ones, how do they move around in the space? What are they doing? You have to be sensitive to what they’re doing […]That’s the only way for adults to get any ideas about what to do with the space, and what to bring into it. (Johansson and Hultgren Citation2015, 56– 57).

The implementation level

The implementation level translates the ontological and ideological levels into practice through activities, meetings, design and artefacts. When participation is defined as being part of a collective where one is respected and included regardless of age or other differences and as an ongoing process, promoting participation entails finding ways of including, involving, inspiring and challenging the library visitor.

Inclusion

Inclusion is a precondition for participation – the child that is not included can neither participate nor influence. Inclusion goes beyond stating that everyone is welcome; people can be excluded on a number of grounds: physical, linguistic or cognitive ability, age, or social and economic factors. Inclusion thus implies the possibility for everyone that belongs to the target group to be able to attend. A library’s inclusiveness has to be extended to children’s caregivers and this implies that certain requirements must be met that fulfil even their expectations. Convenience (physical, functional and psychological) proved to be an important issue when it came to inclusion. Information about the activities must be disseminated in a way that does not exclude people due to language or not having the appropriate contacts.

It must be easy to get there. Is there a carpark, a nearby bus-stop? Are there possibilities for heating babyfood and having coffee? A secure pram park is essential. A not insignificant aspect for parents jostling with feeding and sleeping times is that entrance is free and the library is open every day.

Inclusion is manifested in physical arrangements – small children should be able to see and reach materials by themselves. In the cultural centre for children project the staff went beyond normal public access requirements in the form of wheelchair ramps and toilets for disabled in their planning. They considered how they could further enable a sense of community and participation. For instance, in a room designed primarily for reading they installed a seating gallery in three tiers in the form of curved open carpeted steps rather than sofas which can be occupied by some thus excluding others. Neither did they want the floor to be the only seating option which can be uncomfortable for some adults, grandparents in particular. The seating gallery provides plenty of space and at the same time captures the attention of toddlers learning to climb and walk.

Inspiration

Inspiration concerns the affordances of the place: it should be a place that invites exploring, exciting experiences, creative activities, stimulation of all senses and opportunities to extend the body's possibilities. According to the parents who participated in focus groups it is also important that children can ‘make their mark’, at least temporarily. Horton and Kraftl (Citation2006, 272) argue that events, feelings and actions connected to places make them meaningful and ‘more than mere containers for action’ (c.f. Gallacher Citation2005). According to Jones (Citation2000:30) an attractive space that stimulates creativity should be ‘otherable’ i.e unfinished and possible to alter in interaction with the specific situation and the specific visitors. In Borås a space was created that is largely empty and thus open for different types of activities – a performance or a story telling session. The walls can be used temporarily for film projections, for instance, of a babbling brook in the forest. Sound and lighting can also be used to create different atmospheres and things can be placed in the room to attract the interest of the visitor. The idea behind this flexibility is that the room is always recognizable in itself to its young visitors but at the same time can afford a new challenge or experience on each visit.

In the first project the staff worked with technologies to inspire and engage, for instance digital touch screens built into shelves at toddlers’ eye-level. Tunnels under specially designed book-boxes invite crawling and discovery, and floors that slope slightly challenge toddlers learning to walk. Dens, steps and corners to turn, stools that can be rolled, climbed on, sat on or used to build things with invite and inspire. Generously proportioned armchairs and sofas invite relaxation and reading experiences.

The following extract is taken from our field notes on the inauguration of the renovated library in Malmö:

Two brothers pass by. ‘Shall we climb up there?’ suggests one of the boys and points at the ladder up to a den. They regard the ladder for a little while in silence; then the boy who suggested climbing climbs up while the other watches. When he reaches the den he shouts happily that it was easy ‘I’m up now!’ and his little brother accepts the challenge and climbs up too. […] I see a little 2 year-old boy inside the hollow ‘tree’. The entrance is too small for an adult. He smiles at me and says ‘I can stand in here!’ (Johansson and Hultgren Citation2018, 33)

Involvement

Involvement refers to active participation in creating the activity or place. It can be achieved in several ways. Before the environment was formed and during the process the project leaders in both Borås and Malmö interviewed parents and observed the visitors’ movements and doings in each setting. In Malmö they also engaged children in workshops with different tasks and followed up with feedback from the groups. For example, they made a new classification system with the help of children, taking their departure point in children’s ways of categorizing. A part of the environment was designed with inspiration from children’s suggestions of a forest with dens, and an acknowledgement of these efforts came from a boy who saw the place for the first time and exclaimed: ‘I recognize everything here. We did it!’

The final name of the children’s library in Malmö, Kanini, was the result of another kind of participation where children were invited to suggest names that the inhabitants of Malmö later voted on. A third kind of participation is when visitors can continually influence the room. In both libraries there are boards and shelves to exhibit children’s creations. In Malmö, they also have a ‘Squiggle machine’, a large digital device with a happy face and a hole in its ‘stomach’, into which children can feed drawings. When the child presses a button, the image of the drawing ‘flies’ out into the library environment and dances around on a wall.

Challenge

Challenge means that the environment includes not-yet defined in-between spaces; that the room is ambiguous, there are more things to explore, understand and define. The room and the things in it as well as the staff challenge the children, and the children in turn challenge the room. It is not a place for delivering education, where the adult tries to inform the children of adult understandings, nor a place for free play, but a social space where adults and children interact with each other, the things and the environment.

The following excerpt from our fieldnotes in The Cultural Centre project in Borås is taken from an expedition with preschoolers and their teachers to the local open air museum:

The museum curator points out a large round stone called ‘the lifting stone’, she explains that many years ago, when labourers were looking for work, the employers would only take on the strongest men. Whoever could lift the stone would get the job – ‘Like Pippi’ said one girl [referring to Astrid Lindgren’s character Pippi Longstocking, the strongest girl in the world]. All the children immediately wanted to try and lift the stone but it won’t budge. A boy suggests that we adults try. We can’t budge it either. Everyone joins in the effort to move the stone and we manage to lift it up on one side. Underneath there’s a note, it says ‘Pontus was here’. At the children’s suggestion, the curator writes ‘XX preschool was here too’ and puts the note back. The children are delighted.

Being able to play in a library environment is also important because today children are inspired by stories and genres offered through a whole range of media platforms – film, computer games, tv-series, books and toys. The reference in the excerpt above ‘Like Pippi’ could be a child making sense of what it means to be strong and using cultural references to do so. Children use stories to play and they express themselves culturally through play as well as creating their cultural identities as children.

In summary, a view of children as individuals who can contribute and an environment that includes, inspires, involves and challenges entails creating an ‘enabling’ environment and holding an ‘enabling’ view of childhood.

Testing, experimenting and reflecting

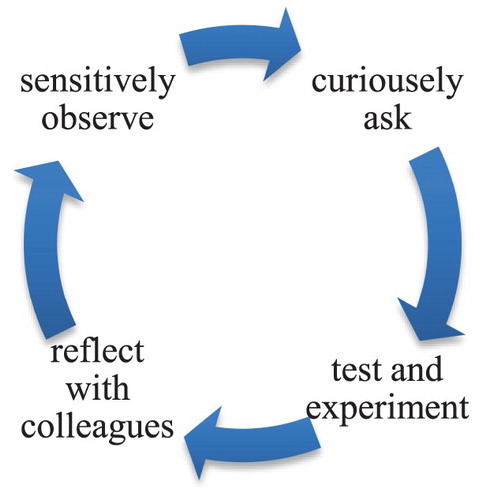

In the research projects we observed that the staff developed ways of working with participation that we summarize in the diagram below: .

Louise Holt (Citation2004) addresses the issue of relations between children and adults from an ethical perspective through the concept of ‘empowering research’, which includes not just the methodology, but the whole research practice. It means that the researcher – and in our case also the librarian – needs to be self-reflexive and aware of his/her own subjective role in power relations The staff in Malmö worked methodically by building on their understandings through communication with the visitors, the room and their colleagues. We illustrate this method through a hermeneutic circle beginning where the staff sensitively observe and inquire how the library and its materials are being used and how they themselves interact with their visitors and curiously put questions to them in order to get more information. Based on these observations they introduce changes on an ongoing basis in the environment or in the ways in which they treat visitors. They observe the effects of different interventions and discuss their experiences with colleagues. Staff development is thus a naturally recurring phase in the circle. Hermeneutic circles are actually spirals where a preconception forms the basis of a preliminary interpretation which is then tested and leads to a deepened understanding. This in turn has repercussions on activities and how they are interpreted. Each turn in the spiral implies deeper understanding of the phenomenon of interest. This approach is characterized by the ambition to develop the library as a place for children’s own agendas where children are acknowledged as fellow citizens but also as ‘interdependent with others’ (Moss and Petrie Citation2002, 107).

One part of the experimental activities was that in Malmö the staff gave themselves special assignments to carry out during two week periods. These assignments became fruitful exercises not only for finding ways of promoting children’ s participation but also for the staff themselves to discover what happens when they leave their own comfort zones. One such assignment was to test the difference between greeting each visitor – or not to say anything at all. In another assignment the staff equipped themselves with tool belts decorated with colourful badges and full of small things that stuck up over the edges of pockets – an iPad, a toy. Yet another was to wear slippers in the shape of animals – hedgehogs and rabbits, etc. – or to wear funny hats. The following comment was posted on the library’s blog:

We bought the belts to see if they would make us more visible in the library to our visitors and also to carry practical things in. We soon found that we could include things that aroused the children’s interest and curiosity and that opened the way for conversations and meetings. (Johansson and Hultgren Citation2018, 34)

A simple experiment in the library had quite a considerable impact. The staff set up a board with a large paper on it and a supply of coloured pens. Above they placed a sign that read ‘Hi, we’re called Catharina and Lisa. What are you called?’ The idea was that as children usually like writing their names, to invite them to make an impression by writing them on the board. The board was placed in the entrance to the library and immediately noticed. It soon became a ‘must’. The task itself is an easy one, most children over a certain age can write their names, it can be done quickly and does not require reflection. By writing your name you demonstrate that you are there, you ‘write yourself’ into the room and it is likely that it strengthens children’s sense of belonging. On one occasion the board was replaced with a notice with information about a cancelled storytime, but the visitors wrote their names on it anyway. This suggests that they had made it their own, it had become a ‘children’s place’ (Rasmussen Citation2004). Another aspect of the nameboard connects it to the CRC (Citation1989); article 7 accords all children the right to their own name, a name is an individual’s unique characteristic, that which separates us from others. To call someone by their name is to recognize the other person and to be called by your name is to be seen. Knowing someone’s name is the basis of a relationship. The staff found that the children seemed to like being called by their names and that it made it easier to communicate with them:

Knowing a child’s name is really important, the child is seen as an individual. Sometimes when I’m showing the library [to groups] they can spread out, but if I know their names it’s easier to capture their attention. Names build relationships and participation (Johansson and Hultgren Citation2018, 40)

The child citizen

The empirical studies have allowed us to identify how children and parents ‘do’ participation in embodied ways and through interaction with others and things. We see participation as people doing things together, each making their own unique and valuable contributions and where even the desire not to participate or only a little is respected. The model of participation we present here describes participation as processual, observable and as happening in the meeting between people, places and things. Focus is on the process itself and the opening of lines of communication rather than on the outcomes of particular activities.

Our point of departure is thus that a model of participation must first be equally applicable to all children, regardless of age or other differences and secondly, that participation is not defined once and for all, but constantly redefined during the process of every specific activity or situation. Such an enabling approach presupposes that every child is met as an individual and not as a representative of a category. The difference – in age, gender, origin, ability – is the point of departure and enriches the possibilities of the affordances of the place. We often think the other way around; we presuppose a specific child when we think of participation, for example a child that is verbal, social and cooperative. Equality then tends to be equated with sameness.

Citizenship is often interpreted on the basis of rights and responsibilities that not all citizens can live up to (Davis and Hill Citation2006). Citizenship, according to Moosa-Mitha (Citation2005), has always been a question of inclusion and exclusion. A traditional view of citizenship includes the right to vote, to participate in political decision-making, to get married and the right to be an independent economic actor (Marshall Citation1997). From being reserved for male, property-owning adults, citizenship has become the right of every adult over the age of 18 in Sweden. In this light children are ‘nearly citizens’.

However, if citizenship is defined on the basis of the participation people exercise through living in a society, then it cannot be something they qualify for through status, age or competence. Rather, it is society that must qualify itself to attend to all its citizens’ competences and citizenship is understood as inclusive and built on the idea that people are differently equal and equally valuable. This puts focus on a society where process and not results are its most important aspects and where communication between people is held open. In this sense children’s libraries can constitute a forum for active citizenship.

In its broadest meaning participation is about being a member of society and includes both adults and children. In a rights and citizen perspective based on difference each library visitor is met as ‘another’ in the sense someone who has a unique perspective and can contribute something. For a library that is in a continuous relational participation process, each visitor is valuable and the library is welcoming, not just to all but to each and every one.

Acknowledgements

We thank the children and staff who worked with us in Borås and Malmö.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Anuerin Smith, T., and R. Dunkley. 2018. “Technology-Nonhuman-Child Assemblages: Reconceptualising Rural Childhood Roaming.” Children’s Geographies 16 (3): 304–318. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2017.1407406

- Benwell, M. C. 2013. “Rethinking Conceptualisations of Adult-imposed Restriction and Children’s Experiences of Autonomy in Outdoor Space.” Children’s Geographies 11 (1): 23–43. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2013.743279

- Bishop, J. C., and M. Curtis. 2001. “Introduction.” In Play Today in the Primary School Playground: Life, Learning and Creativity, 1–20. Buckingham, PA: Open University.

- Cele, S., and D. van Burgt. 2015. “Participation, Consultation, Confusion: Professionals’ Understandings of Children's Participation in Physical Planning.” Children's Geographies 13 (1): 14–29. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2013.827873

- Christensen, P. 2004. “Children’s Participation in Ethnographic Research: Issues of Power and Representation.” Children and Society 18: 165–176. doi: 10.1002/chi.823

- Clark, J., and S. Richards. 2017. “The Cherished Conceits of Research with Children: Does Seeking the Agentic Voice of the Child Through Participatory Methods Deliver What it Promises?” In Researching Children and Youth: Methodological Issues, Strategies, and Innovations, edited by I. E. Castro, M. Swauger B, and B. Harger, 127–148. Bingley: Emerald.

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx.

- Corsaro, W. A. 1985. Friendship and Peer Culture in the Early Years. Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex.

- Davis, J. M., and M. Hill. 2006. “Introduction.” In Children, Young People and Social Inclusion: Participation for What?, edited by K. M. Tisdall, J. M. Davis, M. Hill, and A. Prout, 1–19. Bristol: University of Bristol Policy Press.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophreniza. London: Athlone.

- Gallacher, L. 2005. “‘The Terrible Twos’: Gaining Control in the Nursery.” Children’s Geographies 3 (2): 243–264. doi: 10.1080/14733280500161677

- Gallacher, L.-A., and M. Gallagher. 2008. “Methodological Immaturity in Childhood Research? Thinking Through ‘Participatory Methods’.” Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark) 15 (4): 499–516.

- Hart, R. 1997. Children’s Participation: the Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care. New York: UNICEF.

- Hart, R. 2008. “Stepping Back From ‘the Ladder’: Reflections on a Model of Participatory Work with Children.” In Participation and Learning: Perspectives on Education and the Environment, Health and Sustainability, edited by A. Reid, B. Bruun Jensen, J. Nikel, and V. Simovska, 19–31. Dordrecht: Springer Link.

- Holt, L. 2004. “The ‘Voices’ of Children: De-centring Empowering Research Relations.” Children’s Geographies 2 (1): 13–27. doi: 10.1080/1473328032000168732

- Holt, L. 2013. “Exploring the Emergence of the Subject in Power: Infant Geographies.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 31: 645–663. doi: 10.1068/d12711

- Horgan, D., C. Forde, S. Marin, and A. Parker. 2016. “Children’s Participation: Moving From the Performative to the Social.” Children’s Geographies 15 (3): 274–288. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2016.1219022

- Horton, J., and P. Kraftl. 2006. “Not Just Growing up, Butgoing on: Materials, Spacings, Bodies, Situations.” Children's Geographies 4 (3): 259–276. doi: 10.1080/14733280601005518

- Hvenegaard Rasmussen, C., and H. Jochumsen. 2010. “Från Läsesal Till Levande Bibliotek – Barn, Ungdomar och Biblioteksrummet.” In Barnet, Platsen, Tiden. Teorier och Forskning i Barnbibliotekets Omvärld, edited by K. Rydsjö, F. Hultgren, and L. Limberg, 213–240. Stockholm: Regionbibliotek Stockholm.

- IFLA. 2017. More about IFLA. https://www.ifla.org/about/more.

- James, A., and A. Prout. 1997. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood: Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood. London: Routledge.

- Johannesen, N., and N. Sandvik. 2009. Små Barns Delaktighet och Inflytande – Några Perspektiv. Stockholm: Liber.

- Johansson, B. 2005. Barn i Konsumtionssamhället. Stockholm: Norstedts Akademiska Förlag.

- Johansson, B., and F. Hultgren. 2015. Rum för de Yngsta: Barns och Föräldrars Delaktighet i Kulturverksamheter. Borås: University of Borås.

- Johansson, B., and F. Hultgren. 2018. Att utforma ett barnbibliotek tillsammans med barn: delaktighetsprocesser på Malmöstadsbibliotek. Borås: University of Borås.

- Jones, O. 2000. “Melting Geography: Purity, Disorder, Childhood and Space.” In Children’s Geographies: Playing, Living, Learning, edited by S. Halloway and G. Valentine, 28–47. London: Routledge.

- Leckie, G. J., and J. Hopkins. 2002. “The Public Place of Central Libraries: Findings From Toronto and Vancouver.” The Library Quarterly 72 (3): 326–372. doi: 10.1086/lq.72.3.40039762

- Lee, N. 2001. Childhood and Society: Growing Up in an Age of Uncertainty. Maidenhead: Open University.

- Lee, N. 2005. Childhood and human value: development, separation and separability. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Malmö stad. 2015. Lilla Slottet – följ med på resan mot det nya barnbiblioteket! Blog post, 31 April 2015. https://projektlillaslottet.wordpress.com/2015/04/ and https://projektlillaslottet.wordpress.com/2015/02/ [8 August 2017]

- Marshall, K. 1997. Children’s Rights in the Balance: The Participation – Protection Debate. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office.

- Mayall, B. 2002. Children’s Childhoods: Observed and Experienced. London: Falmer Press.

- Mcneish, D. 1999. “Promoting Participation for Children and Young People: Some Key Questions for Health and Social Welfare Organisations.” Journal of Social Work Practice 13 (2): 191–203. doi: 10.1080/026505399103403

- Moosa-Mitha, M. 2005. “A Difference-centered Alternative to Theorization of Children’s Citizenship Rights.” Citizenship Studies 9 (4): 369–388. doi: 10.1080/13621020500211354

- Moss, P., and P. Petrie. 2002. From Children’s Services to Children’s Spaces: Public Policy, Children and Childhood. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Nordenfors, M. 2010. Delaktighet – på Barns Villkor? Gothenburg: Rådet Tryggare och Mänskligare Göteborg. http://www.tryggaremanskligare.goteborg.se/pdf/publikation/Delaktighet_pa_barns_villkor_web.pdf.

- Olsson, L. M. 2009. Movement and Experimentation in Young Children’s Learning: Deleuze and Guattari in Early Childhood Education. London: Routledge.

- Prout, A. 2005. The Future of Childhood. London: Routledge Falmer Press.

- Rasmussen, K. 2004. “Places for Children – Children’s Places.” Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark) 11 (2): 155–173.

- Richards, S., J. Clark, and A. Boggis. 2015. Ethical Research with Children: Untold Narratives and Taboos. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sandin, A. S. 2011. Barnbibliotek och Lässtimulans: Delaktighet, Förhållningssätt, Samarbete. Stockholm: Region bibliotek.

- Shier, H. 2001. “Pathways to Participation: Openings, Opportunities and Obligations.” Children & Society 15: 107–117. doi: 10.1002/chi.617

- Skar, Gundersen, and L. O’Brien. 2016. “How to Engage Children with Nature: why not Just let Them Play?” Children’s Geographies 14 (5): 527–540. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2015.1136734

- Skolverket. 2003. Ung i demokratin: gymnasieelevers kunskaper och attityder i demokrati-och samhällsfrågor. Stockholm: Skolverket. [Swedish National Agency for Education 2003 Young in Democracy: high school pupils’ knowledge of and attitudes to democracy and societal issues].

- Smith, F., and J. Barker. 2000. “Contested Spaces: Children’s Experiences of out-of-School Care in England and Wales.” Childhood, a Global Journal of Childhood Research 73: 315–333. doi: 10.1177/0907568200007003005

- Thomson, J. L., and C. Philo. 2004. “Playful Spaces? A Social Geography of Children’s Play in Livingston, Scotland.” Children’s Geographies 2 (1): 111–130. doi: 10.1080/1473328032000168804

- Wall, J. 2010. Ethics in Light of Childhood. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Wall, J. 2017. Children's Rights: Today's Global Challenge. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Little.

- Wyness, M. 2013. “Global Standards and Deficit Childhoods: the Contested Meaning of Children's Participation.” Children’s Geographies 11 (3): 340–353. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2013.812280