ABSTRACT

Local play parks are key spaces within children’s geographies providing opportunities for physical activity, socialisation and a connection with their local community. The design of these key neighbourhood facilities influences their use; extending beyond accessibility and installation of equipment when seeking to create a location with usability for all. This paper reports on the development of an evaluation tool, which supports the review and development processes linked to play parks. The Play Park Evaluation Tool (PPET), which is evidence-based in content and developed with a multi-disciplinary approach drawing on disciplines from the Built Environment and Health Sciences (occupational therapy), considers key areas contributing to the accessibility and usability of play parks. Aspects evaluated include non-play features such as surface finish and seating, recognising the relevance of these in creating accessible, usable spaces for play. This alongside assessment of installed play equipment to evaluate the breadth of play options available and how these meet the needs of children and young people with varying abilities or needs. The paper describes PPET’s creation, the revision process undertaken, and its subsequent use across three stages of a play park’s development. Key to achieving facilities with high play value is the provision of a varied play experience. To support this the evaluation of play types offered is integrated within the tool. This in-depth appraisal is supported by the creation of an infographic illustrating the resulting data and provides a method by which this information is presented in an accessible form. This visual representation contributing to the decision-making process undertaken by those responsible for the provision of play parks.

Introduction

Diverse factors need consideration to ensure that play park provision offers varied play experiences and facilitates use by all. This paper demonstrates adopting a holistic approach to evaluating play park provision; considering environmental aspects alongside play value and provision for those with additional needs. This was achieved through the development of a Play Park Evaluation Tool (PPET), whole site evaluation informing creation of a play value infographic, highlighting play types; accessible and usable equipment. This is the unique approach to evaluate the key attribute of PPET.

It is appropriate that this paper is viewed within the concept of children’s geographies; including geographies of children and young adults with mind–body-emotional differences.

A re-focusing of approaches to human geography reflecting the Social Model of Disability developed by Hall and Wilton (Citation2017) recognises our capacity to create exclusionary and/or enabling environments, challenging us to adopt different approaches to support access or engagement with environments or everyday geographies. This Non-Representational Theory approach directs academic enquiry towards the physicality and experience of the active world (Andrews Citation2018). The social model challenges assumptions and pre-conceptions influencing legislation and international agreements. Children’s right to play is enshrined in Article 31 of the UN Convention on the rights of the child (United Nations Citation1989), and the Equality Act (Citation2010) legislates for equal access to environments and facilities within the United Kingdom (UK).

PPET content is evidence-based, developed with a multi-disciplinary approach combining academic and real-life influences. The first author, an occupational therapist, establishing the evidence-base through a wide-ranging literature review and utilising her professional experience; supported by colleagues with expertise in built environment design. The literature review identified studies directly informing the development of PPET. These are listed in and, where referenced within this paper, highlighted with the relevant number.

Table 1. Evidence supporting PPET development.

Play parks as spaces for play

The spaces children experience and interact with are key to their health and social development (Chaudhury et al. Citation2019). Children’s understanding and use of locations differ from that of adults requiring consideration of this in the context of outdoor play. Independent access to locations including play parks is often achieved through stages negotiated with, and curated by parents (Nansen et al. Citation2015).

For children, interactions between spaces, experiences, and social contacts create locations with value and meaning (13). Play and social opportunities afforded by play parks identify them as key within children’s geographies (Chaudhury et al. Citation2019; Jansson Citation2015). Benwell (Citation2013, 40) proposes communities ‘should strive to create geographies which enable some amount of independent engagement with outdoor space’. Therefore, access to play parks cannot be considered in isolation as children’s geographies reflect their sense of space (Christensen, Mygind, and Bentsen Citation2015), social interactions (Bourke Citation2017), and independent mobility (Nansen et al. Citation2015).

The design of these key local facilities influences their use (1,4,14); extending beyond accessibility and installation of equipment when seeking to create a location with usability for all. How a site is laid out influences use; placement of items providing affordances promoting the use of equipment and movement between items (4) offering different experiences and challenges. Hussein (Citation2017) considered the affordances identified by Heft and Kytta, adding to these providing a summary of how play park design provides a range of invitations to play.

Current UK local play park provision suggests this play environment is freely available, however, this is not guaranteed. Altered parental attitudes towards children’s free-time increase structured activities and reduces independent mobility (Barron Citation2013). Concerns including traffic, bullying, and stranger-danger contribute to ‘helicopter’ or over-parenting. Cultural values can impose restrictions, and Karsten (Citation2003) notes girls from some ethnic groups are absent from play parks. These issues, alongside home-based digital entertainment, reduces outdoor free-play.

Also absent from many play parks are children with differing abilities (15,17,18), their need for varied play opportunities as significant as for other children. Stephens et al. (Citation2017, 593) conclude this population ‘continuously face accessibility barriers and challenges impacting on health and development’ within the built environment. Limited consideration of the needs of this user group directly influences play opportunities they experience (11,12,24). Evidence shows children with differing abilities can experience meaningful play within play parks (3). This may appear to differ from the way their peers engage with equipment and environments (16) (Wenger et al. Citation2021). Research considering access to outdoor play identifies physical obstacles restricting opportunities for those with additional needs (8,9,10,11,12) and societal barriers (Wenger et al. Citation2021).

Studies identified that although the establishment of play parks aims to provide high-quality outdoor play, intentions to meet a community’s identified need are not universally achieved (8). Solomon (Citation2005) notes differences between local and regional provision, the latter more comprehensive. Woolley (Citation2007) describes the homogenous design approach of local play facilitates as Kit, Fence, Carpet; equipment enclosed by fencing and set in safety surfacing, designs dissociated from their settings. Absence of diversity perhaps reflecting the limited use of available guidance and evidence supporting design decisions, and enabling evaluation of provision (10,21).

Benefits derived from play in play parks

Children’s play is experienced across different locations having associated benefits and is influenced by the setting (23). Commonly outdoor play occurs in gardens, educational settings, and in key locations within a child’s home-range (Woolley and Griffin Citation2015).

Tovey (Citation2007) advises that more physically active play is found in outdoor environments, possibly through larger spaces and reduced adult oversight. The Health Committee report (House of Commons Citation2018) highlights that an estimated one-third of UK children between 2 and 15 are overweight or obese. Responding to this through increasing physical play opportunities is universally recognised as valuable (WHO Citation2016).

Children benefit from play in community facilities (1); design standards and site maintenance minimising risks. Fixed items of play equipment facilitate the development of physical skills including balance and motor skills (Clements Citation2004). Musculoskeletal changes linked to physical activity are supplemented by other benefits including longer focal ranges preventing myopia (McBrian, Morgan, and Mutti Citation2009), and sun exposure promoting levels of vitamin D. Additionally, sensory inputs including vestibular and proprioceptive stimuli, aid skill development including coordination. Health benefits extend to mental health. Frampton, Jenkin, and Waters (Citation2014) note positive effects on children’s well-being and self-esteem; experiencing success and failure builds resilience in managing associated emotions (1).

Play parks provide opportunities to develop life skills enabling ‘individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life’ (UNICEF Citation2003). Peer interactions require life skills to minimise friction. Reduced adult oversight necessitates an understanding of turn-taking; collaboration, and negotiation (McClain and Vandermaas-Peeler Citation2016). Within a child’s home-range play parks are locations where they experience increasing autonomy and independent mobility; journeys to and from play parks increasing familiarity and connection with community and locale (Prezza and Pacilli Citation2007).

Risk management strategies minimise the chance of injury during active play, alongside increased self-esteem through successful negotiation of challenges. The systemic review of risky outdoor play and associated impact on children’s health completed by Brussoni et al. (Citation2015, 6448) concluded that promotion of this play type has value in enabling active healthy lifestyles; including increased play time, social interactions, creativity, and resilience.

The literature review afforded an overview of the current themes regarding play park provision enabling the identification of key aspects for data collection supporting site evaluations thus contributing to the creation of PPET. Understanding of associated play types facilitated the identification of play value features and informed the play value infographic.

Evaluation of play park provision

Investigation of how decision-making affects provision requires consideration across different sites and effective data collection. The literature review identified that research on play park provision focuses on specific themes including assessment and management of risk, accessibility, usability, inclusion, and play types (5,8,9,11,21,22).

Risk assessment inspections enable the management and maintenance of UK play parks. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA Citation2016) advises these must meet European Safety Standards (EN1176, Part 7), and this management process is well supported through training, checklists and schedules.

The variation in terms adopted to illustrate the remaining aspects of provision are summarised below providing context within this paper:

Accessibility: non-play aspects (parking, pathways, seating); through the objective evaluation of provision (Iwarsson and Stahl Citation2003).

Usability: play equipment design supporting use by individuals with differing levels of ability, encompassing Universal Design and focusing on an individual’s subjective evaluation of their experience (Iwarsson and Stahl Citation2003).

Inclusion: environments that can be used by as many individuals as possible on as many occasions as possible (Prellwitz and Skär Citation2007).

Play types: physical, imaginative, or cognitive play, plus sensations including speed, rotation, and tactile experiences.

Internet searches identified tools and publications supporting data collection when reviewing play park provision including:

ADA Checklist: play areas (Institute for Human Centred Design Citation2011)

BTG-COMP Park observation tool (Board of Trustees of University of Illinois Citation2012)

Me2 Checklist (Playcore Citation2015)

Plan Inclusive Play Checklist (InclusivePlay.com Citation2015)

The literature review identified academic studies considering accessibility of play parks. Play parks in Norrland (Sweden) are assessed as inaccessible for those with restricted mobility (12), and that site designs lack opportunities for those with differing abilities (7,9,10,11,13,14,15,17). Additionally, the impact of societal barriers was described as influential (3,17). Play types are identified in the literature with differing interpretations, one considers human-relational aspects (observation of others; solo/interactive play) (18). An alternative adopted headings from the Playwork sector including environmental, physiological, and fantasy play (23).

These resources and their use in data collection were considered in relation to the research question. For this investigation, data collection encompassed three themes: accessibility, usability, and play type, no single resource capturing this breadth of data. To facilitate data collection a holistic evaluation form (PPET) was developed which is identified as a key contribution to this aspect of play provision.

PPET development

Key aspects of play park provision from the literature review (accessibility, usability, site location and design, and equipment selection) were considered by the first author reflecting professional experience alongside understanding of access to play by children with differing abilities. This was supplemented by grey materials and play park site visits. Real-life experience enabling the analysis of play opportunities/experiences offered by items of equipment, and the physical or cognitive abilities required for their use. This confirmed the key aspects of play park provision as accessibility; inclusion of those with differing needs through enabling use by all members of a community (5), and breadth of play types.

Evaluating a play park and its location requires comprehensive data collection. Key environmental aspects including accessibility are usually evaluated independently from play experience appraisal, it is this disconnect PPET intends to address. Initially, this is achieved by recording data within a single document, recording of topography, installed equipment, and play value encompassing usability for individual aspects. This interconnection is enhanced through the creation of a play value infographic illustrating play choices and highlighting options for those with differing abilities.

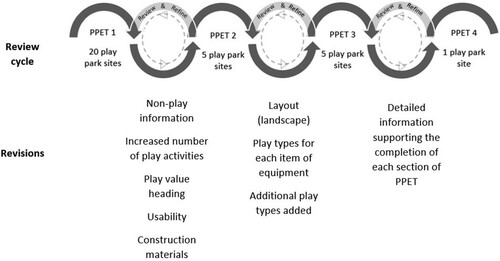

To achieve an effective tool PPET underwent a series of revisions illustrated in .

The initial document consisted of the following:

access to the location

play park entrance/s

internal access

items of equipment

play activities offered

The development process required four revisions (PPET1-4). A 20-site pilot study was completed (PPET1) updated the document to PPET2. This pilot study seeking to establish if the current provision was accessible and inclusive and identifying available activities. Use of PPET2 demonstrated revision was required enabling data collection of non-play aspects including wayfinding and toilets (PPET3). Aligning PPET3 with the literature review ‘play activities’ was retitled ‘play value’. This section recording all play activities represented, noting facilitation of play for users with differing abilities. Further refinement included re-formatting to landscape orientation and clarification of terms such as ‘hanging or monkey bars’ with information on different designs of equipment (e.g. swing types) supporting the understanding of the data required. Supporting identification of play value, section 5 (installed play equipment), was revised to list play types adjacent to each item of equipment facilitating evaluation.

Enabling consistent data collection across sites required an additional version of PPET. PPET4 providing descriptors facilitating understanding of what information is required and guidance on its relevance. Accessibility and usability of play parks are considered key design aspects; PPET4 supports consideration of the needs of a wide range of users, including adults supporting children’s access. Those responsible for play parks have a duty to consider and meet the access needs of diverse populations. PPET4 supports site evaluations by volunteer providers who are unlikely to have previous experience in this area. Information and explanations in PPET4 assist with minimising the impact of the subjectivity of those completing PPET3; subjectivity an issue noted by Perry et.al. (11) in their post-use evaluation of the PARCS tool. (Copies of PPET3/4 are available on request from the lead author).

The validation process initiated for PPET contributes to its refinement to ensure inter-rater reliability (at single sites and multiple locations) minimising the impact of subjectivity through clarifying the information gathering intent for each section. This validation process is the focus of a future paper. PPET’s paper-based format has potential for development as a web tool or app enabling the inclusion of advice and clarification of terminology.

Play type

PPET use highlighted the need to facilitate recording of play types to support play value evaluation. Following review changes include expansion of play types; additional headings and activity-based descriptors including non-physical play: imaginative play, cognitive activities (activity boards); sensory play (visual, auditory, tactile experiences); and human interactions facilitated through play equipment design. These descriptors illustrate how equipment supports alternative use, e.g. play structures as social spaces rather than for imaginative play. The play types reflect information from the literature review aligned with activity analysis creating a comprehensive list of typical play park activities. Limited universally accepted terminology for play types required the adoption of terms from different disciplines including occupational therapy to provide appropriate descriptors as follows:

Solitary play: equipment effectively used without others (slide)

Social play: equipment promoting socialisation during play (climbing frame with platforms)

Cooperative play: equipment requiring two or more users (seesaw)

Parallel play: two users concurrently complete the same activity (swings)

Linear play: equipment requiring turn-taking (traditional slides, tunnel)

Commonly installed play equipment promotes physical or active play; however, this is not the only play experience found in play parks (3,13). PPET enables the evaluation of play opportunities promoting cognitive and imaginative play including activity boards, play structures, sand, and water play.

PPET: accessibility, usability, and play value

Whilst this paper focuses on play value as one aspect of provision, PPET recognises that different facets combine to support access by adults and children with differing needs when accessing play parks.

‘Accessibility’ can describe environmental and societal aspects supporting or impeding people’s ability to enter or move within defined areas. This a key factor in the context of play parks. However, the ability to actively engage with both space and equipment to experience play activities is better encompassed by the use of the term ‘usability’. Hurst and Lee (5) note a focus on the creation of usable facilities has positive benefits for the general population. Reflecting this in PPET ‘accessibility’ relates to the ability to reach or enter environments; relating to a location within the built environment; landscape or topography.

In this context, inclusion and usability have relevance; for consistency ‘usability’ is adopted emphasising that both site and equipment should be usable by all. Play equipment design facilitates its use; adoption of usability recognises both size and design of equipment alongside physical skills and cognitive ability required for effective and safe use.

Within PPET the above aspects of provision are considered separately to offer play experiences, Play value within PPET evaluated through consideration of the following aspects:

number of individual items of play equipment

different play experiences/types offered

different levels of complexity/difficulty for each equipment type/play experience

lists aspects of provision contributing to play value combining literature review findings with properties identified during the review cycle; examples of equipment facilitating these given in parentheses.

Table 2. Aspects contributing to play value.

Physical play aspects relate to movement types afforded by equipment e.g. zip wires providing a sliding motion, or physical requirement for use e.g. climbing up/over objects to achieve height. Not all play involves movement or physical effort. Non-physical play refers to play activity not focused on physical effort or motion, encompassing sensory, cognitive, and imaginative options. Equipment facilitating non-physical play includes sound tubes, musical chimes, mirrors, play structures, and activity boards. It is recognised that physical play, for example on a swing or seesaw, has non-physical elements, however, these are not the equipment’s primary function. Additionally, equipment dictates children’s interactions with others during play, seesaws requiring cooperation and linear play on slides facilitated by turn-taking.

Currently, there is no universal term describing aspects of play park provision encompassed by play value, alternatives include ‘play richness’ and ‘playability’. Although not clearly defined by Perry et al. (11) the term ‘play richness’ is used alongside accessibility and usability as a key aspect of play park provision. They note the need to address non-physical play highlighting benefits of visual, olfactory, tactile, and auditory stimulation demonstrating how this provision meets the needs of users with differing abilities. ‘Playability’, is adopted by Yantzi et al. (24), Wilson (Citation2012), and Czalczynska-Podolska (4). The descriptor specified by Yantzi et al. most closely aligning to play value in PPET, differentiating between accessibility and play opportunities. They position playability as provision facilitating play between children of different abilities; specialist, accessible equipment situated within the main play area.

Play value infographic

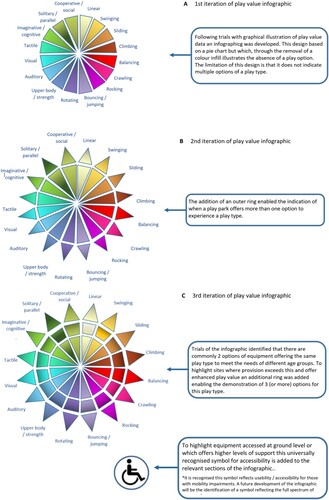

PPET provides data from site evaluations but does not illustrate play value in an accessible manner, requiring a visual representation of this. Achieving this in a format illustrating both play value and highlighting provision for those with differing needs was not achievable through graphical representation. The pie-chart presentation represented collated data, however, its binary nature prevented illustration of multiple options for a single play type and does not highlight the absence of play options.

illustrates the stages of infographic development from a pie-chart concept. The initial design illustrates data for single play types or activities, the colour wheel presentation adding visual impact. Development through the addition of outer rings enables the indication of multiple options of play types. Where all sections are filled this indicates a minimum of three opportunities within a play type is available.

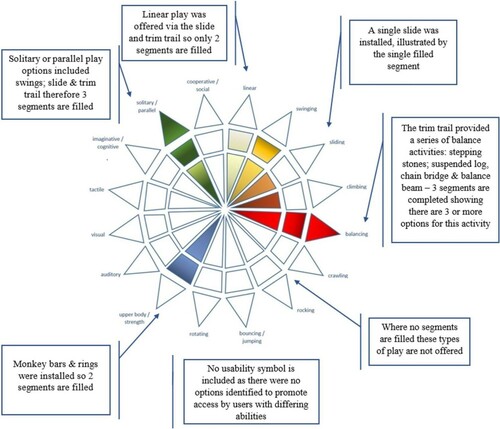

The review cycle identified that the two-section infographic did not reflect the play value offered in many locations, the addition of an outer ring resolving this issue. The inclusion of a symbol highlighting usable play opportunities indicates ground-level activities supporting those with mobility impairments; items offering multiple access options; and different equipment designs offering varying levels of support. The removal of the colour infill from individual segments indicates absence of these play options. demonstrates how the completion of the infographic for the original provision at the case study play park (described below) highlighted installed equipment and the absence of usable options.

In the current iteration of the infographic, the presence of items of play equipment supporting play by those with differing abilities is highlighted by the addition of a symbol depicting a wheelchair user () reflecting the International Symbol of Access. The review of this icon is required as it emphasises mobility over usability across a diverse population. The clarity of any icon used necessitates consideration within different formats.

PPET in use

PPET is primarily designed for use at existing sites to identify areas for development, but is also effective in reviewing proposed developments. This dual-purpose further supports the provision of high-quality provision promoting play for children with differing abilities.

PPET’s ability to evidence effective play provision across key areas is illustrated through a case study site evaluation. The site is located in an East Midlands village (population 4500), the original play park re-sited with all play equipment replaced. This was considered an opportunity to review both provision and play park position, an incidental benefit being an increase in adjacent car parking.

The original site was adjacent to a road; accessed from the pavement or through a 24-space car park. One proposal relocated provision 250 m across a green area away from both road and car park re-using some existing equipment. This was revised, locating new equipment within the green area bordering the original site, expanding the parking area, and maintaining direct access to the play park. The current provision is illustrated in .

Site redevelopment aligned with the development of PPET enabling its use at the original site; evaluation of the proposed scheme, and appraisal of the new installation. Completing these evaluations evidenced the value of PPET, indicating its appropriateness for use at other sites supporting the selection of additional equipment and the redevelopment process. This enabled the authors to compare three stages of development culminating with an evaluation of the final installation and its play value (the responsible body authorised use of PPET during the redevelopment but as it had not been validated results were not shared and did not influence decision-making).

PPET is divided into six sections; five providing a structure to evaluate a site’s physical attributes and noting installed equipment. Section 6 is designed to facilitate the evaluation of the play value offered and the creation of the infographic. The data gathered in sections 1–4 is not illustrated through figures or numerical scores as their purpose is to stimulate discussion. The headings offer opportunities to reflect on decision-making, enabling the review of key non-play aspects.

Non-play aspects of provision

Section 1 considers factors influencing access to a site including parking, public transport, and lighting. Play park sites generally remain in their original position with no alteration to these aspects. For the site under discussion completion of section 1 for proposed locations could have facilitated discussion of access options, highlighting how one option increased distance from the road, provided a single access point via the car park and additional groundworks for a pathway. This reduced one risk factor (road proximity) but added an additional hazard (navigating a car park). The final location is a compromise placing the play park within the green area retaining access via the car park.

The three subsequent PPET sections evaluate entrance points, internal access, and non-play equipment. Section sub-headings direct the evaluation process; PPET4 providing detailed guidance on aspects for consideration and the reasoning supporting their inclusion.

Individual sections highlight areas of provision which can be manipulated or adjusted by those with responsibility for the play park. Aspects including transport links and road speed limits cannot be directly shaped at a local level but might influence the selection of a play park’s location. For the case study site, PPET evaluation of sections 1–4 was restricted to the original and current installations as the proposal drawings and specification focused on play equipment and seating.

Evaluation of play provision

Section 5 considers the provision of fixed items of play equipment. Information gathered includes play type and non-physical play opportunities an item of equipment offers. PPET supports this evaluation through the listing of common equipment designs aiding their identification. Additionally, its design allows reflection on how children interact with equipment (solitary/cooperative/linear play), and how its design and position within a site facilitate or inhibit use considering the associated affordances. The data collection can be enhanced by photographic records enabling later recall and clarification of aspects of provision.

Combining on-site evaluation with additional information and images facilitates discussion and reflection but does not summarise findings in a manner expressing the associated outcomes of provision.

Section 6 collates fixed play equipment data numerically, listing the total number of items of equipment and/or play types present. This nominal data highlight where play park users with differing abilities are supported.

In sections 5 and 6, space is provided for notes and narrative alongside recording of the nominal data within each category supporting the understanding of aspects influencing usability.

illustrates how this data enables the creation of an infographic representing play value through a presentation of nominal data for four aspects of play. Relevant segments of the infographic are completed illustrating data for the development stages across four play types; column A providing data for the total number of items of a play type, and column B for the number of different options supporting this play type.

Table 3. Nominal data and infographics across original, proposed and current provision.

Thus, for the original provision, the key data for swings is not that there are four provided, closer evaluation highlights only two designs are installed. This restricts the use to those small enough to be lifted/fit into bucket swings and those with the physical and cognitive abilities to utilise flat seat swings. This contrasts with the proposed and current scheme where swing type options have increased.

Column B data for swinging, sliding, balancing, and rocking play options, is used to populate the infographics within the table demonstrating how this information is illustrated. Where equipment choice enables users with differing abilities opportunity to experience similar play experiences this is indicated by the addition of a symbol to highlight usability.

The impact of equipment choice or design on the ability of those with differing abilities to experience play types is illustrated in . Images A–C show common designs for swings. The first (A) requires users to have trunk control and support themselves as they initiate and maintain the swinging motion. B has a ‘bucket style’ design offering trunk support for younger users and for those supporting their play to swing with them. The nest-style swing (C) allows those unable to maintain a sitting position to have full-body support whilst swinging. The seesaw (D) requires users to be stood, offering less support than the ‘traditional’ seated design (E) but the wide platform at the centre of F would allow the activity to be experienced by a user unable to maintain a seated position. It is acknowledged that some designs offering additional support through back rests (e.g. B and F) impact the ease of access often requiring users to be lifted in/out of the seat.

Dependent on the design, equipment may offer a number of play options. For example, a nest swing suspended from a single attachment point offers linear and rotational movements and supports solitary and social play.

Comparison of infographics in for the original and proposed schemes demonstrates an increase in play type options, highlighting the inclusion of equipment with different levels of difficulty or complexity. Highlighting items of equipment easily accessed or simpler to use illustrates how the previous provision lacked usable play options. Final scheme revisions (current provision) add balance as a play option via a trim trail. Its 10 linked activities: ground-level ‘bridge’ with railings, fixed balance beam, single-strand rope-bridge, suspended balance beam, and stepping stones demonstrate how different designs offer varying levels of difficulty. Children can select activities based on current ability with opportunities to master more complex items. The ground-level ‘bridge’ an easily used item of equipment, whilst suspended balance beams and rope-bridge require balance skills and confidence. Comparison of the infographics for the proposed and completed schemes illustrates the addition of balance as a play option, however, the accessible auditory activity (speech tube) is now absent. Overall, the current provision has markedly increased play value offering additional play opportunities or increased access. Inclusion of cognitive/imaginative, visual, rotational, rocking, and crawling activities is reflected in the difference between the infographics.

Discussion

Current processes for the design and refurbishment of play parks result in variable standards of provision with the potential for these high-cost facilities to lack essential play elements. Support from equipment suppliers and groups such as Play England (Shackell et al. Citation2008) is invaluable, however, consultations completed by the first author identify a lack of awareness of available resources, and that evidence from academic investigations including those in is viewed as neither accessible nor relevant at a grass-root level.

Play parks, as key local play locations (6), should reflect their environment and the play preferences of local users, therefore it is appropriate they are created by communities and users. Limited support for site evaluation and equipment selection has in the past resulted in homogenous provision (Solomon Citation2005; Woolley Citation2007).

Providers can influence design by creating effective, usable provision (8), this process would be enhanced through easily accessible support to evaluate existing or proposed play parks. Financial considerations affect funding for equipment or the creation of sites; high costs associated with development require effective utilisation of funds. Awareness is growing of the need to consider wider aspects of provision, including accessibility and play value, rather than simply the number and size of play equipment. This is reflected in studies including those by Woolley (21,23); Hurst and Lee (5), Jeanes and Magee (8), and Moore and Lynch (9). Promotion of accessibility and usability for those with disabilities is recognised outside of academia as a key requirement for play park provision, enabling use by a diverse population (Shackell et al. Citation2008).

Prevalence of a binary approach to facilities for children within the built environment, considering the population as either disabled/non-disabled or impaired/non-impaired (Holt Citation2016), was reflected in participant responses in the study reported. Holt (Citation2016) highlights how this does not reflect the continuum of differences found in children and young adults, a population including those who may not identify themselves as ‘disabled’ such as some within the d/Deaf community.

This disconnected focus on accessibility and usability has, in our view, a potential to ‘other’ those requiring additional support by identifying them as a separate population. Differentiating between the needs of user groups potentially emphasises a perceived need for ‘specialist’ and/or separate provision; marginalising rather than promoting inclusion. Addressing this disconnect PPET facilitates evaluation of provision for all users, as opposed to focusing on specified areas such as inclusive play removing the separation between provision for those with and without disabilities.

Numerical representation of data is possible, an arbitrary minimum score indicating a minimum level of provision. This may add bias to the evaluation, scores ‘adjusted’ to meet this subjective standard. Presentation of PPET data will influence users’ approach to evaluations. Illustrating play value and usability data through an image remove this goal-based option, enabling adjustment through the identification of available and absent play options. Additionally, the infographic demonstrates both different options for play and provides a method to highlight enhanced play value. Combining this information with a tally of usable play opportunities through the use of an icon supports those with additional needs in considering their specific requirements for play.

This combination highlights the challenge faced by playpark providers. Moving from a position viewing and evaluating ‘general’ and ‘specialist’ provisions separately, towards a holistic approach. One considering accessibility, usability, and play value for all users of play parks, promoting inclusion and supporting provision of effective play facilities. The play value infographic offers an opportunity to illustrate site-specific play opportunities () via use in signage, on promotional documents and on digital platforms.

Limitations and future research

The authors recognise that this paper reports the initial PPET and infographic development and that further refinement is required. The present iteration provides a northern European perspective, temperate climates reducing consideration of shade, and reflects the availability of published research by western scholars. Initial validation highlighted this within the vocabulary used in PPET, evidencing a need to remove technical terminology to increase the accessibility of the tool. As noted previously further validation is required, and it is intended that this will combine with the creation of a digital version of PPET considering the language and terminology used, use by adults and children, professional and non-professionals, and support methods for completion of PPET including illustrations as well as ensuring it is relevant and applicable outside of the UK.

Conclusion

The need to provide effective outdoor play locations has increased the awareness of the impact of design and selection of play equipment (4,6,7). Research evidence that these influence both user population and frequency of use (5,6,14). In the built environment the appraisal of existing and new buildings (post-occupancy evaluation) is established practice; users’ feedback examined through a range of mechanisms. Adapting this approach to play park design enhances the quality and inclusivity of provision, moving away from considering provision for people with additional needs separately from the general population. The current practice appears incompatible with a focus on increased inclusion needing to adapt to ensure accessible and usable play parks. Early development of PPET suggests this has the potential to support decision-making promoting effective play park provision with high play value. Its use, alongside the play value infographic, will support the creation of play parks meeting the needs of a wide range of users promoting use by diverse populations. In line with Holt et al. (Citation2015) play parks have the capacity to be a hub of local interaction with enhanced social value for communities, contributing to a sense of community as well as facilitating active free-play.

Whilst the study described did not elicit the voices and experiences of children and young adults, it can be argued that further revision of the language, terminology and accessibility of both PPET and the infographic offers means and opportunity to increase children’s involvement in the design and development of play parks. The inclusive approach encompassed within PPET reflects the move from a binary approach towards one which is designed to be inclusive and accessible for all.

Additionally, PPET offers opportunities as a training and educational tool for play park providers, through its emphasis on access and inclusion and the reflective process required to complete the play value infographic. To achieve this, both the tool and infographic require ongoing refinement and deployment to ensure their content and design have relevance and are accessible to all users.

Acknowledgments

The work presented in this article was carried out by the first author under the supervision of the second author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andrews, G. 2018. Non-representational Theory & Health: The Health in Life in Space-Time Revealing. Abingdon:Routledge.

- Barron, C. 2013. “Physical Activity Play in Local Housing Estates and Child Wellness in Ireland.” International Journal of Play 2 (3): 220–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2013.861262.

- Benwell, M. 2013. “Rethinking Conceptualisations of Adult-imposed Restriction and Children’s Experiences of Autonomy in Outdoor Space.” Children’s Geographies 11 (1): 28–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.743279.

- Board of Trustees of University of Illinois. 2012. “BTG-COMP Park Observation Tool.” http://www.bridgingthegapresearch.org/_asset/vnb0e7/BTGCOMP_Park_2012.pdf.

- Bourke, J. 2017. “Children’s Experiences of Their Everyday Walks Through a Complex Urban Landscape of Belonging.” Children's Geographies 15 (1): 93–106.

- Brussoni, M., R. Gibbons, C. Gray, T. Ishikawa, E. Sandseter, A. Bienenstock, G. Chabot, et al. 2015. “What Is the Relationship Between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 12 (6): 6423–6454.

- Chaudhury, M., E. Hinckson, H. Badland, and M. Oliver. 2019. “Children’s Independence and Affordances Experienced in the Context of Public Open Spaces: A Study of Diverse Inner-City and Suburban Neighbourhoods in Auckland, New Zealand.” Children’s Geographies 17 (1): 49–63.

- Christensen, J., L. Mygind, and P. Bentsen. 2015. “Conceptions of Place: Approaching Space, Children and Physical Activity.” Children’s Geographies 13 (5): 589–603.

- Clements, R. 2004. “An Investigation of the Status of Outdoor Play.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 5 (1): 68–81.

- Equality Act. 2010. c.15. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents (Accessed: 4 June 2020).

- Frampton, I., R. Jenkin, and P. Waters. 2014. “Researching the Benefits of the Outdoor Environment for Children.” In Early Years Education and Care: New Issues for Practice from Research, edited by S. Hay, 125–140. London: Routledge.

- Hall, Edward, and Robert Wilton. 2017. “Towards a Relational Geography of Disability.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (6): 727–744.

- Holt, L. 2016. “Geographies of Young Disabled People.” In Identities and Subjectivities, Volume 2 of Skelton, T. (ed) The Springer Handbook of Geographies of Children and Youth, edited by N. Worth and C. Dwyer, 23–50. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-981-287-022-3.

- Holt, N., H. Lee, C. Millar, and J. Spence. 2015. “‘Eyes on Where Children Play’: A Retrospective Study of Active Free Play.” Children’s Geographies. 2 13 (1): 73–88.

- House of Commons Health Committee. 2018. Childhood Obesity: Time for Action. London: House of Commons.

- Hussein, H. 2017. “Sensory Affordances in Outdoor Play Environment Towards Well-being of Special Schooled Children.” Intelligent Buildings International 9 (3): 148–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17508975.2015.1015945.

- Inclusive Play. 2015. Inclusive Play. Accessed July 13, 2017. http://www.inclusiveplay.com/.

- Institute for Human Centered Design. 2011. ADA Checklist for Existing Facilities. 20 (2): 65–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.857646. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.adachecklist.org/checklist.html

- Iwarsson, S., and A. Stahl. 2003. “Accessibility, Usability and Universal Design Positioning and Definition of Concepts Describing Person-Environment Relationships.” Disability Rehabilitation 25 (2): 57–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/dre.25.2.57.66.

- Jansson, M. 2015. “Children’s Perspectives on Playground Use as Basis for Children’s Participation in Local Play Space Management.” Local Environment 20 (2): 165–179.

- Karsten, L. 2003. “Children’s Use of Public Space: The Gendered World of the Playground.” Childhood 10 (4): 457–473. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568203104005.

- McBrian, N., I. Morgan, and D. Mutti. 2009. “What’s Hot in Myopia Research – The 12th International Myopia Conference, Australia, July 2008.” Optometry and Vision Science 86 (1): 2–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181940364.

- McClain, C., and M. Vandermaas-Peeler. 2016. “Social Contexts of Development in Natural Outdoor Environments: Children’s Motor Activities, Personal Challenges and Peer Interactions at the River and the Creek.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 16 (1): 31–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2015.1050682.

- Nansen, B., L. Gibbs, C. MacDougall, F. Vetere, N. Ross, and J. McKendrick. 2015. “Children’s Interdependent Mobility: Compositions, Collaborations and Compromises.” Children’s Geographies 13 (4): 467–481.

- Playcore. 2015. “Inclusive Play.” Accessed September 12, 2015. http://www.playcore.com/inclusive-playgrounds.html.

- Prellwitz, M., and L. Skär. 2007. “Usability of Playgrounds for Children with Different Abilities.” Occupational Therapy International 14 (3): 144–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.230.

- Prezza, M., and M. Pacilli. 2007. “Current Fear of Crime, Sense of Community, and Loneliness in Italian Adolescents: The Role of Autonomous Mobility and Play During Childhood.” Journal of Community Psychology 35 (2): 151–170.

- RoSPA. 2016. “Inspection and Maintenance of Playgrounds.” Accessed July 28, 2018. https://www.rospa.com/play-safety/advice/inspection-maintenance/.

- Shackell, A., N. Butler, P. Doyle, and D. Ball. 2008. “Design for Play: A Guide to Creating Successful Play Spaces.” http://www.playengland.org.uk/media/70684/design-for-play.pdf.

- Solomon, S. 2005. American Playgrounds: Revitalizing Community Space. Hanover: University Press of New England.

- Stephens, L., K. Spalding, H. Aslam, H. Scott, S. Ruddick, N. Young, and N. McKeever. 2017. “Inaccessible Childhoods: Evaluating Accessibility in Homes, Schools and Neighbourhoods with Disabled Children.” Children’s Geographies 15 (5): 583–599.

- Tamm, M., and L. Skär. 2000. “How I Play: Roles and Relations in the Play Situations of Children with Restricted Mobility.” Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 7 (4): 174–182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/110381200300008715.

- Tovey, H. 2007. Playing Outdoors: Spaces and Places, Risk and Challenge. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- UNICEF. 2003. “Life Skills: Definition of Terms.” Accessed July 8 2015. http://www.unicef.org/lifeskills/index_7308.html.

- United Nations. 1989. Convention on the Rights of a Child. Article 31.

- Wenger, I., C. Schulze, U. Lundström, and M. Prellwitz. 2021. “Children’s Perceptions of Playing on Inclusive Playgrounds: A Qualitative Study.” Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 28 (2): 136–146.

- WHO. 2016. Report on the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Geneva: WHO.

- Wilson, P. 2012. “Beyond the Gaudy Fence.” International Journal of Play 1 (1): 30–36.

- Woolley, H. 2007. “Where Do the Children Play? How Policies Can Influence Practice.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Municipal Engineer 160 (2): 89–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1680/muen.2007.160.2.89.

- Woolley, H., and G. Griffin. 2015. “Decreasing Experiences of Home Range, Outdoor Spaces, Activities and Companions: Changes Across Three Generations in Sheffield in North England.” Children’s Geographies 13 (6): 677–691.