ABSTRACT

Family reunification is the main reason youth independently migrate from the Global South to the Global North. Research on family reunification adheres to policy definitions of the phenomenon that portray reunification as something that happens within the destination country and within the nuclear family. Yet by following youth mobility trajectories, we show that young people experience many types of family reunification. This paper draws on 18 months of ethnographic fieldwork in Belgium and Ghana with young people of Ghanaian background. We find that for young people, family includes multiple caregivers who are not necessarily nuclear family members, family reunification can at the same time entail family separation, and multiple family reunifications may occur in both the origin and the destination country. Many of these reunifications and separations are significant for youth yet they remain unseen when employing a policy definition of family reunification.

1. Introduction

Family reunification has become one of the main reasons young people migrate from the Global South to the Global North (OECD Citation2017). In Belgium, the main fieldsite for this research, 20,815 young people entered the country for reasons of family reunification in 2017, almost four times the number of minors who sought asylum the same year (Federaal Migratiecentrum Citation2019). According to family reunification laws and policies in many European countries, migrants are allowed to bring a spouse and any minor children to the destination country (European Migration Network Citation2017). ‘Family’ refers only to the nuclear family and family reunification is conceptualized as a phenomenon that takes place within the destination country. This policy and legal definition of family reunification also shapes how the phenomenon is researched. Studies are generally conducted in the Global North, as this is where family reunification laws primarily exist. Research focuses on the effects of reunification policies or on how young people cope with family reunification and integration into the destination country (Strik, de Hart, and Nissen Citation2013; Gindling and Poggio Citation2012; Eremenko and Bennett Citation2018). Research also highlights parent–child separation prior to reunification and the negative consequences of this for parent–child relationships, reflecting the legal and policy focus on the nuclear family (e.g. Artico Citation2003; Suárez-Orozco, Todorova, and Louie Citation2002; Schapiro et al. Citation2013).

A legal and policy perspective, however, is only one way to analyse family reunification and its consequences for youth. This paper foregrounds young people's voices and offers a youth-centric account of family reunification. We combine transnational and mobility perspectives to understand how family reunification is experienced by young people, thereby addressing several shortcomings of a policy perspective in research and practice. First, whereas a policy perspective focuses only on the destination country, a transnational perspective highlights the importance of both migrant origin and destination contexts to better understand migrant realities (Glick Schiller, Basch, and Blanc-Szanton Citation1992; Bryceson and Vuorela Citation2002). The implications of a transnational perspective for how we conceptualize family reunification are large. We show that families often continue to be transnational even after a child is reunited with one or both parents in the destination country, whereas research that takes a policy perspective considers only those living in the new country and ignores the potential importance of people who are not located in the same country as the youth. Second, and relatedly, much research on family reunification considers only the nuclear family, while a transnational perspective helps us to see beyond this. Transnational family studies have criticized the bias toward the Western nuclear family model and urged researchers to reframe ‘the family’ and to take context-specific norms on family and childcare into consideration (Mazzucato and Schans Citation2011). Transnational family research shows the role of extended family members or non-kin caregivers in making transnational families function (Mazzucato and Schans Citation2011; Poeze and Mazzucato Citation2014; Dreby Citation2007; Schmalzbauer Citation2004; Coe et al. Citation2011; Dankyi, Mazzucato, and Manuh Citation2017). Third, a transnational perspective allows us to redefine family reunification. We define family reunification as the act of reunifying with a person or persons whom the young person perceives as being or having been their primary caregiver. A primary caregiver is someone who makes a young person feel cared for by providing material, emotional, or financial support. Such care might come from both co-resident caregivers and non-co-resident caregivers, such as migrant parents abroad.

While a transnational perspective casts light on cross-border relationships, scholars have pointed to the need to combine it with a mobility lens (van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018; Schapendonk and Steel Citation2014). Mobility scholars focus on all types of mobilities, not just migration. They explore mundane everyday movements, such as commutes or visits to family and friends, and how these affect people's lived experiences (Sheller and Urry Citation2006). By looking at migration through a mobilities lens, we come to see how the continuous mobility that migration may engender, affects cross-border relationships and young people's perceptions and experiences of separations and reunifications with significant others. Previous work has foregrounded young people's experiences with the “everyday ruptures” that migration entails (Coe et al. Citation2011) and emphasized their agency (Dobson Citation2009; Choi, Yeoh, and Lam Citation2019). Yet youth mobility is still often overlooked in migration research. By focusing on young people's mobility, we view their migration as embedded within a series of moves that can take place before and after their first international move, that is as trajectories (Schapendonk and Steel Citation2014; Schapendonk et al. Citation2018). We contribute to a reconceptualization of family reunification from a youth-centric perspective by using ‘youth mobility trajectories’ as a point of analysis. Youth mobility trajectories are the geographical moves across time and space that young people engage in and the family compositions that result from these moves (Mazzucato Citation2015). Such a focus on youth mobility heeds recent calls for the inclusion of spatio-temporal complexity in migration and youth studies (van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018; Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2018; Cheung Judge, Blazek, and Esson Citation2020).

We thus combine transnational and mobility perspectives to investigate the different family constellations and care arrangements young people are part of to better understand what family reunification means to young people. Drawing on 18 months of multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork in Belgium and Ghana with young people of Ghanaian background (aged 14–25), we show that young people's understanding of family goes beyond the nuclear family, including both extended family members and other caregivers, and that young people accumulate caregivers throughout their lifetime. Family reunification – even with parents – can entail a separation from another person who may have played or continues to play a significant role in a young person's life. This implies that a family, from a youth perspective, remains transnational even if the young person moves to live with both biological parents. Another consequence is that young people can experience multiple family reunifications, both in the Global North and their origin country.

Belgium constitutes an interesting site to study family reunification amongst Ghanaian youth. Belgium is among the top eight countries in the EU for issuing visas for family reasons (European Migration Network Citation2017), and family migration is the single biggest reason migrants enter Belgium (European Migration Network Belgium Citation2017). In 2017, of all residence permits issued for family reasons, 59% were issued to children born abroad who reunified with a parent already living in Belgium (Federaal Migratiecentrum Citation2019). The majority of Ghanaian immigration to Belgium happens through family reunification (Heyse et al. Citation2007). 324 Ghanaians received a long-stay visa for family reunification in 2018, and another 293 applications were rejected (Federaal Migratiecentrum Citation2019). This corresponds to a rejection rate of almost 50%, one of the highest among all nationalities, demonstrating the complexity of the procedure and the tightening conditions for family reunification.

Because of the prevalence of the phenomenon, family migration has remained a political priority. To manage migration flows, family reunification laws have become more stringent in Belgium since 2011. Belgian laws allow reunification of migrants with minor children and spouses yet, in contrast to some EU countries, migrants cannot reunite with adult parents (European Migration Network Citation2017). Belgian law means that the Ghanaian young people of this research have no possibility of reuniting with primary caregivers other than biological parents in Belgium. Only children younger than 18 years of age can reunify with a parent who is a third country national (Agentschap integratie & inburgering, Citationn.d.).

The regulations on family reunification hold central the ideal of the nuclear family. This stands in stark contrast to Belgian family laws and policies for “sedentary families” that recognize a wide diversity of family forms (Sarolea and Merla Citation2020). The reality of family dynamics highlighted in literature on transnational families remains unrecognized in the Belgian family reunification system.

2. The literature on transnational families and family reunification

Young people who do not migrate to join their parents in the Global North are often called ‘stay-behind’ or ‘left-behind’ children (Mazzucato Citation2014). They experience sometimes lengthy periods of separation from one or both parents and sometimes siblings abroad, during which they are cared for either by the second parent or someone else. Studies of such transnational families have explored the situation of these ‘left-behind’ children, the most common themes being the impact of separation on child well-being, parent–child relationships across borders, and childcare arrangements (Jordan and Graham Citation2012; Schmalzbauer Citation2004). Care arrangements are often organized transnationally with family members in different countries contributing to care in various ways (Baldassar and Merla Citation2014). The literature shows that child well-being is shaped differently depending on which parent migrates (Graham and Jordan Citation2011), who the child's caregiver is (Dreby Citation2007) and the stability of care arrangements (Mazzucato et al. Citation2015). Many studies emphasize the negative emotional consequences of separation on both parents (Schmalzbauer Citation2004) and children (Dreby Citation2007), and highlight the vulnerability of ‘left-behind’ children (Castañeda and Buck Citation2011).

Some research acknowledges that the nuclear family cannot be assumed to be the only or best option for children. In the West African context social parenthood and child fostering have long been part of childcare practices (Goody Citation1982), which can shape how care arrangements in transnational families are organized and experienced by ‘left-behind’ children (Alber, Martin, and Notermans Citation2013; Poeze and Mazzucato Citation2014). Consequently, studies have looked at the significance for young people of extended family members or people unrelated by kinship such as teachers, family friends, or fellow church members (Mazzucato and Schans Citation2011).

The caregivers in the origin country are important for a child's well-being in various ways. Caregivers can be a direct source of strength and support (Dankyi Citation2012). The quality of the relationship with a particular caregiver, both in terms of emotional closeness and material resources shared with the child, can mediate parent–child relationships across borders and alleviate potential pain children might feel because of parental absence (Schmalzbauer Citation2004). Caregivers are also important for how they explain parental migration to children, framing it as an act of love or abandonment (Yarris Citation2017). The literature mentioned here mainly focuses on one primary caregiver, with a strong emphasis on female relatives (Schmalzbauer Citation2004; Dreby Citation2007; Dankyi, Mazzucato, and Manuh Citation2017). We will show in this paper that young people can accumulate several caregivers throughout their lifetimes, and that past caregivers often continue to be important for a young person even after they move.

Studies of ‘left-behind’ children have predominantly conceptualized young people as immobile, as implied by the term ‘left-behind’, and only investigated the consequences of parental migration for children in the origin country (Poeze and Mazzucato Citation2014; Mazzucato et al. Citation2015; Hoang et al. Citation2015). Researchers have tended to ignore young people's own mobility because they assume that once the young person moves abroad and reunites with parents, the family stops being transnational. This, however, ignores cases where a child reunites with one parent abroad but remains separated from the other, or where the child joins both parents but leaves behind another caregiver in the origin country. We will show that the family often remains transnational even after a family reunification in the destination country.

In addition to the literature on transnational families, there is a related but separate body of literature on family reunification. Studies in this field are conducted in migrant destination countries in the Global North. These studies rarely employ a transnational perspective and only focus on migrants’ lives after they arrive in the new country. Studies focus on policy frameworks for family reunification and the consequences thereof for migrant families. Scholars investigate what tighter eligibility criteria mean for differential access to family reunification along gender, nationality, family type and class lines (Poeze and Mazzucato Citation2016; Eremenko and González-Ferrer Citation2018), for migrants’ integration into the destination country, and for their feelings of belonging (Bragg and Wong Citation2016; Strik, de Hart, and Nissen Citation2013).

When young people's experiences with family reunification are investigated, this is often done via clinical or therapeutic studies that highlight the negative consequences of parent–child separations on the well-being of reunited children (Mitrani, Santisteban, and Muir Citation2004; Castañeda and Buck Citation2011; Smith, Lalonde, and Johnson Citation2004; Suárez-Orozco, Todorova, and Louie Citation2002; Schapiro et al. Citation2013). Studies explore how the timing of migration and the length of separation affect whether reunification is experienced as traumatic and find that longer periods of separation can negatively affect young people's well-being (Eremenko and Bennett Citation2018). Fewer disruptions in family life are experienced when children establish a solid relationship with their mother before she departs, when separation remains short (Bonizzoni and Leonini Citation2013) and when children reunite at a young age (Fresnoza-Flot Citation2015). All these studies focus on young people's international move and conceive youth mobility primarily in relation to parents’ mobility. Such an adult-centric approach ignores other forms of mobility that young people might engage in, such as moving between households in the origin country.

The mobility and transnational perspective we take in this paper allows us to reconceptualize family reunification from a youth-centric perspective. By focusing on young people's mobility trajectories to investigate the multiple international and national moves young people engage in and how these are experienced in terms of reunifications and concomitant separations from significant others. Our approach allows us to pay attention to migration and reunification as unfolding processes rather than instances in time, heeding recent calls for spatio-temporal complexity in migration and youth studies (Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2018; Cheung Judge, Blazek, and Esson Citation2020; van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018). Furthermore, we examine both origin and destination contexts to understand meaningful relationships across borders as well as context-specific understandings of family. Such an approach moves beyond conventional categories, such as ‘left-behind’ children or ‘reunified’ youth, and brings into focus different family constellations and care arrangements across time and space to better understand what family reunification means to young people.

3. Data and methods

Data for this paper come from the Belgian case study of the ‘MO-TRAYL’ project, led by the second author, which aims to understand youth mobility trajectories and their impact on young people's life outcomes. Multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork, interspersed with communication via social media platforms, was conducted between January 2018 and February 2020. The research participants were based in Belgium and the first author followed their movements over 18 months. Six weeks were spent in Ghana when accompanying young people on trips there, which allowed us to observe interactions with primary caregivers. The close contact in Ghana, usually including co-habitation, and the long-term involvement in the field facilitated relationships of trust between researcher and participants.

Our sample consisted of 25 young people of Ghanaian background who were approached through a snowball technique. All lived in Antwerp or its surroundings, were aged 14–25 at first encounter in the field, and were either born in Ghana or their parents were. Twenty were born in Ghana and came to Belgium for family reunification (four were reunited with both parents, nine with the mother, and seven with the father). Only one of these 20 migrated together with a parent; all others migrated either alone or with siblings. Of the other five, one was born in The Netherlands and migrated to Belgium with his father, and four were born in Belgium. Several informants, including social workers and Ghanaian community leaders, told us that the vast majority of Ghanaian youth in Antwerp were born in Ghana and migrated to Belgium over the course of their lives. This is also reflected in our sample.

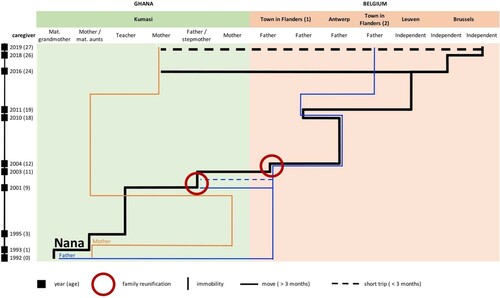

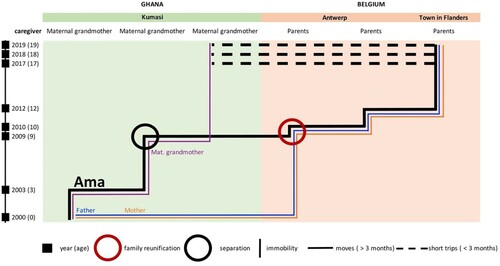

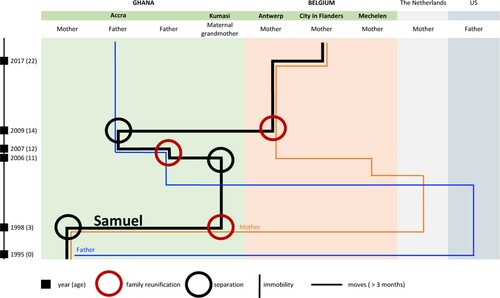

Ethnographic fieldwork consisted of interviews conducted in English or Dutch, informal conversations, and participant-observation in church settings, schools, participants’ homes, and at cultural events. Mapping tools were conducted together with participants to identify their networks and mobility trajectories. Concentric circles mapping identified important people for the youth and their locations in the world and was used to gather information about young people's current and former caregivers. Mobility mapping employed trajectory grids, based on the ‘Ageven grids’ (Antoine, Bry, and Diouf Citation1987), to identify participants’ geographical moves in time and space and concomitant family compositions. Information gathered from mobility trajectory interviews was visualized and the resulting mobility trajectory maps used as interview prompts or to check things with participants. It was through these maps that we first gained insight into changing care arrangements, young people's relationships with significant others and understandings of family. We used thematic analysis and map visualization to identify patterns within the data. This was done by reading and re-reading fieldnotes and visualizations, using both inductive and deductive coding, and subsequently generating, reviewing and defining of themes (Boyatzis Citation1998). Below we present three cases that show the full diversity of elements that constitute what family reunification entails for young people as emerged from the analysis of all 20 cases in which young people had been reunited with caregivers.

4. Young people's understandings of family and family reunification

In this section, we present three vignettes that describe young people's internal and international moves throughout their lifetimes. They show how mobility results in young people having different caregivers at different times and how they grow close to significant others within and outside the nuclear family. Furthermore, the cases show that each reunification also entails a separation from a significant other and that young people can experience multiple family reunifications in different national contexts. Our cases call into question how researchers are best to define and analyse family reunification. All names are pseudonyms.

Nana (27) – living with multiple caregivers throughout childhood

Nana's father migrated abroad when she was an infant and because her mother was very young when Nana was born, several caregivers helped raise her. She first stayed with her maternal grandmother who carried Nana on her back every day when she went to work on her field. Nana got very sick at age one, so her mother and maternal aunts took her in. Nana continued to stay with her aunts even after her mother moved in with her second husband shortly thereafter to start a new family. At the age of three or four, Nana moved in with a teacher and lived in the same neighbourhood as her aunts. Staying on the campus of a very prestigious school, she discovered her love for education and spent much of her time studying. Throughout her childhood, Nana stayed close to previous caregivers: her mother, her grandmother and especially her ‘funny aunt’ who was a teenager at the time and very dear to Nana. She had known her father only from her mother's stories, a couple of phone calls, and some letters and postcards that he had sent from different places abroad. When Nana was nine years old, her father came to Ghana for five months. She described this experience as ‘amazing’. He promised a better life for her in Belgium and she was looking forward to finally living with him. Even though the father's stay in Ghana was temporary, it entailed another relocation for Nana who moved to live with his new wife and Nana's half-siblings in a different neighbourhood, leaving her aunts and friends behind. In order to minimize the time with a family she did not know, Nana asked to be enrolled in a boarding school where she stayed for the next two years. At age 11, Nana moved to Belgium, together with her paternal half-siblings, to be reunited with her father. Over the years, Nana stayed in close contact with her mother and maternal half-siblings in Ghana and grew even closer to them than her paternal half-siblings in Belgium. After finishing tertiary education in Belgium in 2016, Nana moved to Ghana for 6 months, and she made another trip there in 2019 during which she spent time with her mother, siblings and ‘funny aunt’.

Ama (19) – separation from a loved caregiver

Ama grew up with her maternal grandmother, her older sister, and her cousin in Ghana. Her parents had moved to Belgium when she was still an infant, and for much of her life, Ama thought that her grandmother was actually her mother. Even though her biological mother called occasionally and even came to Ghana for visits, Ama had difficulties understanding who her mother was and saw her as a distant family friend. When Ama moved to Belgium with her older sister at the age of nine to be reunited with her parents, it came as a surprise to her. In Belgium, she lived with her parents for the first time in her life, but she felt shy and uncomfortable in the house of ‘strangers’ and longed to be with her grandmother in Ghana. It took time to build up a relationship with her parents, but having a baby brother in Belgium helped, and Ama grew closer to her parents over the years. All the while, her grandmother continued to be important to Ama. They stayed in contact over the phone after Ama moved to Belgium, and Ama continued to receive support and advice from her grandmother. During our concentric circles interview, the grandmother was the only person Ama placed in the innermost circle of ‘most-important people’ because Ama felt she owed so much to her. Since 2017, Ama has been on annual trips to Ghana during which she also visits her grandmother.

Samuel (24) – multiple moves

Samuel was born in Accra and lived with his mother as an only child. His father had moved to the United States when he was a baby. When he was three years old, his mother migrated to Europe and Samuel moved in with his maternal grandmother in Kumasi, a city about 250 km away. He had previously visited his grandmother during holidays and the ‘vibe was there’, as Samuel put it. Samuel's grandmother always wanted him to have ‘that kind of mother love’. She pointed out the gifts and money his mother sent him and made sure that Samuel talked to his mother every day. When Samuel was 11, his grandmother fell ill, and Samuel moved back to Accra to live with his father who had returned from the United States. This move and the separation from his grandmother was a ‘big change’ for him. The relationship with his father, and especially communication between the two, was difficult because they had ‘no vibe’ and no relationship prior to living together. Yet, because Samuel was enrolled in boarding school, he was able to avoid the challenging situation at home, as he only saw his father during the holidays. Having a mother abroad, Samuel anticipated moving eventually and was excited once the opportunity presented itself when he was 14 years old: ‘I was outside having fun and my dad told me to come back early […] because I would be travelling. ‘Where would I be travelling?’ ‘It's a surprise, you don't need to know.’ […] I just showered, freshened up and he took me straight to the airport.’ Samuel flew to Belgium to be reunited with his mother. Looking back on his experience of moving between different households and being cared for by different people, Samuel reflected on the many things he learned in the process: to be independent, responsible and able to cope with difficult times. ‘My journey […], it really helps me to be who I am now.’

4.1. Accumulating caregivers over time

The vignettes above, which we consider in more detail below, illustrate that young people's understanding of family is not limited to the nuclear family, which looms large in policy definitions of family and research on family reunification (e.g. Smith, Lalonde, and Johnson Citation2004). In many instances, caregivers were people other than the biological parents and remained important to young people even after the young person stopped living with them. As such, young people ‘accumulated’ caregivers over time. These multiple caregivers are ignored in most research on ‘left-behind’ children (e.g. Schmalzbauer Citation2004; Dreby Citation2007). While parents, maternal grandmothers, aunts and a teacher were mentioned as taking on caregiving roles in the cases above, other young people in our sample also stayed with a sister, distant family member, or family friend.

Nana's case shows the way care relationships can turn into lasting bonds or have a lasting impact on young people. Nana's mobility trajectory saw her move between various caregivers throughout her childhood: her maternal grandmother, her mother, her maternal aunts, a teacher and fellow church member, her father, her stepmother, and her father again after her migration to Belgium (). Nana spent her early years with extended family members and foster parents despite her mother's presence in Ghana, attesting to mobile kinship practices that have long existed in West Africa and do not only come into play when parents migrate abroad (Poeze and Mazzucato Citation2014). Moving between households was nothing out of the ordinary for the participants in our sample, and when talking about her childhood experiences, Nana emphasized the positive memories she cherished and the people she loved. This contrasts with portrayals of ‘left-behind’ children as vulnerable or suffering because of a separation from a parent abroad (Dreby Citation2007; Castañeda and Buck Citation2011). It is, however, important to acknowledge that young people are not always happy with their caregivers. Nana did not feel comfortable with her stepfamily, and asked to be enrolled in a boarding school.

But many of the people Nana lived with became significant for her. The first year of her life, Nana stayed with her maternal grandmother, accompanying her to the cocoa farm every day. This is something Nana only found out about during her trip to Ghana in 2019 when she asked her mother about her place of birth. The connection she felt to her grandmother immediately made sense to her: ‘This story made me realize why I loved my grandmother so much.’ Nana and her grandmother remained close until her grandmother passed away when Nana was nine. Similarly, Nana stayed connected to other caregivers even after moving to different households. Despite her moves, she stayed in the same neighbourhood for most of her childhood, which allowed frequent get-togethers with her mother and maternal aunts.

Nana's father, whom she had no memories of living with, was also significant to her as a child. Being teased by other children in the neighbourhood for not having a father, Nana started asking her mother questions about him and longed to meet him. She was thrilled to finally see her father when he came to Ghana for five months in 2001, and during another shorter visit the following year. Reflecting on learning about her migration to Belgium, Nana said:

And when I learned that I’m going to live with him, that was also like ‘wow!’ […] he made a lot of promises, like ‘you’re going to have your own room, and you’re going to have your computer’. So I was so happy. […] I was just looking forward to come to where my dad lives and have my own room and my own computer. That was all I was looking [forward] to.

While not all caregiving arrangements involve close emotional bonds, different caregivers can still have benefits for and a lasting impact on young people. At age four, Nana moved in with a teacher who was also the choirmaster of the church Nana and her family attended. Reflecting on this move, Nana said: ‘This master took me in, I don't know what type of agreement he had with my mum, but then, I was just part of that family also.’ Her relocation to the teacher's home on the campus of a prestigious school meant that Nana gained access to educational resources and developed skills needed to succeed in school.

I was so much into school, really so much, it's crazy. You could not separate me from my books or from school. For me, school was the only thing I enjoyed so much growing up. And it's also because of the environment I was brought in[to]. Everything was surrounded with school and studying.

4.2. Family separation

Having multiple caregivers over time implies that family reunification will also entail a separation from previous caregivers. Separations can be more or less meaningful for young people, depending on their attachment to the former caregiver and their relationship with the parent(s) they are reuniting with.

Ama's case demonstrates how separation can have strong emotional implications. Ama grew up with her maternal grandmother in Ghana before moving to Belgium at the age of nine to join her biological parents (). Ama had little understanding that her parents had been living in Belgium and assumed that her grandmother was her mother. She did not understand at the time that her parents were trying to provide a better life for her by moving her to Belgium, nor did she anticipate her own migration. Her separation from her grandmother came as a shock.

I was young, I didn't even know that I was coming here [Belgium] until I was at the airport and needed to let go of my grandma and I was crying. A day I will never forget. I said to my grandma ‘come with me’. My grandma was crying ‘I can't come with you, I can't come with you’.

[My parents] were just strangers to me […], it was always weird, I was always silent. My sister … she had a bond with them because she was older and she could talk to them. But I was always silent, did not have anything to say. […] In the beginning, I really wanted to go back to Ghana, I was fed up with here [Belgium], I wanted to see my grandmother. I did not like it here.

Ama also longed to visit her grandmother in Ghana, and she went on a trip there for the first time at age 17.

At that time, I had been here [Belgium] for 10 years. And I did not see my grandmother. The first time [I went to Ghana] was first and foremost because of my grandmother. I wanted to see her. I really wanted to see her.

For other young people, separation was less problematic and family reunification proceeded more smoothly. Nana's reunification with her father in Belgium was not as disruptive for her because she had met her father when he came to Ghana for two home visits. Furthermore, she did not have a close emotional attachment to her two previous caregivers, the choirmaster of her church and her stepmother. Similarly, Samuel did not experience problems reunifying with his mother in Belgium even though his father stayed behind in Ghana. Samuel and his mother had maintained a close transnational relationship over the years and had a closer emotional attachment than Samuel and his father, and Samuel was looking forward to living with his mother again.

Studies of family reunification in destination countries show that there are fewer disruptions to family life and child well-being when separation remains short and children reunite at a young age (Eremenko and Bennett Citation2018; Fresnoza-Flot Citation2015; Bonizzoni and Leonini Citation2013). But besides length of separation and time of migration, our research shows the need to also consider how young people experience relationships with primary caregivers in both origin and destination contexts. Taking a transnational and mobility lens to the cases above provides evidence about the importance of the primary caregivers who accumulate over a young person's lifetime and whether a family separation and a subsequent reunification are experienced as meaningful and/or disruptive.

4.3. Multiple family reunifications in origin and destination countries

Young people may not only reunite with family once in the destination country, as research and policy often suggest (e.g. Suárez-Orozco, Todorova, and Louie Citation2002), but can experience multiple family reunifications in both origin and destination countries. Consequently, they can also experience multiple family separations. To illustrate this point, we analyse Samuel's case.

Samuel stayed with his mother in Accra until she migrated to Europe when he was three and Samuel relocated to his maternal grandmother's in Kumasi (). Talking about his experiences, Samuel said: ‘It was really easy to catch up with [my grandmother]. Because she always treated me like my mum treated me but even more pampering.’ Samuel felt reunited with part of his family when he moved to his grandmother's house because of his prior relationship with her. He had always seen his grandmother as a caregiver. At the age of eleven, Samuel experienced a second family reunification when his grandmother became too sick to take care of him and he moved back to the capital city to live with his father. Even though Samuel had not previously met his father, he understood his father's role as a parent based on the many stories he had heard: ‘You know when seeing your dad, […] it's somewhat like … you get to hear so many things about your dad and it's just like, ‘oh! So it's him!’ So that's what my dad was like.’ Despite this, Samuel's relationship with his father was strained and he soon went to boarding school.

Samuel's first two changes of household described above, to his grandmother's and to his father's, are usually not considered family reunifications in the literature because they do not take place with a nuclear family member and/or not in the destination country. The only move that would normally be considered a family reunification in Samuel's mobility trajectory is his migration to Belgium at age 14 to join his mother, which he was very excited about: ‘[Reunifying] with my mum it's like, I know her already, I have seen her already. And you really miss her, so you just get to see her, like, 'damn, I really missed you!’ How a young person experiences family reunification can thus vary greatly, depending on the kind of relationship the young person has with the caregivers they both join and leave behind.

Separated from his previous caregivers, Samuel stayed in contact with them through transnational communication. He emphasized the different things he learned from each: his grandmother taught him how to be respectful and ‘don't talk back’, his father taught him how to be ‘disciplined’, and staying in a boarding school helped him become more ‘independent’. Samuel's case highlights the importance of considering both origin and destination contexts if we are to fully understand young people's experiences with family reunification and separation.

5. Conclusion

This paper has analysed the mobility trajectories of young people of Ghanaian background in an effort to reconceptualize family reunification from a youth-centric perspective, thereby adding to research on transnational families, ‘left-behind’ children and family reunification. Young people's reunification with parents, usually in the Global North, is a common phenomenon. Research has adopted definitions of family reunification as used in policy and law, and has consequently focused on the destination country and the nuclear family. Less attention has been paid to family reunification from the perspectives of young people. We acknowledge young people as active agents in migration processes (Dobson Citation2009), and focus on young people's own mobility patterns, which often differ from those of their parents.

Combining mobility and transnational perspectives, this paper makes several theoretical contributions. First, our research carries insights on the complexity of transnational families to research on family reunification. We acknowledge significant others beyond the biological parents and context-specific norms on family and child-rearing (Mazzucato and Schans Citation2011). We have shown that young people can have a diversity of caregivers throughout their lifetimes, including their biological parents, extended family members or non-kin, and that they continue to have meaningful relationships with caregivers even across nation-state borders. We have demonstrated that young people often understand such an accumulation of caregivers as enriching, in contrast to previous research on ‘left-behind’ and reunified youth which is mainly concerned with the negative consequences of parental migration (e.g. Artico Citation2003; Schapiro et al. Citation2013; Dreby Citation2007). Family, as understood by our young respondents, includes people they have lived with and who have cared for them over their lifetimes, even from afar. This is a more encompassing definition of family than that used in family reunification policies in the Global North that only consider children under the age of 18 and their biological parents. Based on a context-specific and youth-centric understanding of family, we redefine family reunification as the act of reuniting with a person or persons whom the young person perceives as a primary caregiver.

Second, we have shown that both destination and origin contexts are important when seeking to understand young people's experiences with family reunifications. A focus on youth mobility trajectories – defined as a young person's moves and the family constellations that result from these moves – allows us to recognize that family reunification also entails separation from significant others. If this separation takes place when young people migrate internationally, from a young person's perspective, the family continues to exist transnationally. This finding only becomes apparent when employing a transnational perspective. Young people often deal with separation from significant others by frequent communication and visits, which further shapes their mobility trajectories. Our research thus helps to correct a bias in transnational family literature, which has focused on children ‘left-behind’ in the origin country. This focus has an implicit assumption that when children move themselves to reunite with parents, the family is no longer transnational. But young people's mobility trajectories provide clear evidence to the contrary.

Lastly, our transnational and mobility perspective has shown that young people can experience multiple family reunifications both in destination and origin countries. In contrast, current approaches in research and policy only focus on one reunification, that taking place in the destination country, as though a young person's life was a clean slate before arriving to the new country. Several of the young people we interviewed experienced multiple separations and/or reunifications in both countries. It is therefore important to understand how a family reunification that takes place within the context of international migration may be embedded within a broader series of reunifications and separations that take place before or after the international move. This complex mobility and the shifting family constellations that result remain under-researched in both family reunification and transnational family literatures.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Noel Clycq, Roy Huijsmans, Ester Serra Mingot, the MO-TRAYL team, and two reviewers for their valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agentschap integratie & inburgering. n.d. “Gezinshereniging.” https://www.agii.be/thema/vreemdelingenrecht-internationaal-privaatrecht/verblijfsrecht-uitwijzing-reizen/gezinshereniging.

- Alber, Erdmute, Jeannett Martin, and Catrien Notermans. 2013. Child Fostering in West Africa: New Perspectives on Theory and Practices. Boston: Brill.

- Antoine, Philippe, Xavier Bry, and Pap Demba Diouf. 1987. “The ‘Ageven’ Record: A Tool for the Collection of Retrospective Data.” Survey Methodology 13 (2): 163–171.

- Artico, Ceres I. 2003. Latino Families Broken by Immigration: The Adolescent's Perceptions. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing.

- Baldassar, Loretta, and Laura Merla. 2014. Transnational Families, Migration and the Circulation of Care: Understanding Mobility and Absence in Family Life, Routledge Research in Transnationalism; 29. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bonizzoni, Paola, and L. Leonini. 2013. “Shifting Geographical Configurations in Migrant Families: Narratives of Children Reunited with Their Mothers in Italy.” Comparative Population Studies 38 (2): 465–498. doi:https://doi.org/10.4232/10.CPoS-2013-01en.

- Boyatzis, Richard E. 1998. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bragg, Bronwyn, and Lloyd L Wong. 2016. “‘Cancelled Dreams’: Family Reunification and Shifting Canadian Immigration Policy.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 14 (1): 46–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2015.1011364.

- Bryceson, Deborah Fahy, and Ulla Vuorela. 2002. The Transnational Family: New European Frontiers and Global Networks. Oxford: Berg.

- Castañeda, Ernesto, and Lesley Buck. 2011. “Remittances, Transnational Parenting, and the Children Left Behind: Economic and Psychological Implications.” The Latin Americanist 55 (4): 85–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1557-203X.2011.01136.x.

- Cheung Judge, Ruth, Matej Blazek, and James Esson. 2020. “Transnational Youth Mobilities: Emotions, Inequities, and Temporalities.” Population, Space and Place 26 (6): e2307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2307.

- Choi, Susanne YP, Brenda SA Yeoh, and Theodora Lam. 2019. “Editorial Introduction: Situated Agency in the Context of Research on Children, Migration, and Family in Asia.” Population, Space and Place 25 (3): e2149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2149.

- Coe, Cati, Rachel R. Reynolds, Deborah A. Boehm, Julia Meredith Hess, and Heather Rae-Espinoza. 2011. Everyday Ruptures: Children, Youth, and Migration in Global Perspective. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Dankyi, Ernestina. 2012. “Growing Up in a Transnational Household: A Study of Children of International Migrants in Accra, Ghana.” Ghana Studies 14: 133-161. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/ghs.2011.0004.

- Dankyi, Ernestina, Valentina Mazzucato, and Takyiwaa Manuh. 2017. “Reciprocity in Global Social Protection: Providing Care for Migrants’ Children.” Oxford Development Studies 45 (1): 80–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2015.1124078.

- Dobson, Madeleine E. 2009. “Unpacking Children in Migration Research.” Children's Geographies 7 (3): 355–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280903024514.

- Dreby, Joanna. 2007. “Children and Power in Mexican Transnational Families.” Journal of Marriage and Family 69 (4): 1050–1064. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00430.x.

- Eremenko, Tatiana, and Rachel Bennett. 2018. “Linking the Family Context of Migration During Childhood to the Well-Being of Young Adults: Evidence from the UK and France.” Population, Space and Place 24 (7): e2164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2164.

- Eremenko, Tatiana, and Amparo González-Ferrer. 2018. “Transnational Families and Child Migration to France and Spain. The Role of Family Type and Immigration Policies.” Population, Space and Place 24 (7): e2163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2163.

- European Migration Network. 2017. “Family Reunification of Third–Country Nationals in the EU Plus Norway: National Practices.”

- European Migration Network Belgium. 2017. “Family Reunification with Third Country National Sponsors in Belgium.”

- Federaal Migratiecentrum. 2019. “Migratie in Cijfers en Rechten 2019.”

- Fresnoza-Flot, Asuncion. 2015. “The Bumpy Landscape of Family Reunification: Experiences of First- and 1.5-Generation Filipinos in France.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (7): 1152–1171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.956711.

- Gindling, Thomas, and Sara Poggio. 2012. “Family Separation and Reunification as a Factor in the Educational Success of Immigrant Children.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (7): 1155–1173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.681458.

- Glick Schiller, Nina, Linda Basch, and Cristina Blanc-Szanton. 1992. “Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 645 (1): 1–24.

- Goody, Esther N. 1982. Parenthood and Social Reproduction: Fostering and Occupational Roles in West Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Graham, Elspeth, and Lucy P. Jordan. 2011. “Migrant Parents and the Psychological Well-Being of Left-Behind Children in Southeast Asia.” Journal of Marriage and Family 73 (4): 763–787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00844.x.

- Heyse, Petra, Fernando Pauwels, Johan Wets, and Christiane Timmerman. 2007. "Liefde kent geen grenzen: Een kwantitatieve en kwalitatieve analyse van huwelijksmigratie vanuit Marokko, Turkije, Oost Europa en Zuid Oost Azië." Brussels: Centrum voor gelijkheid van kansen en voor racismebestrijding.

- Hoang, Lan Anh, Theodora Lam, Brenda SA Yeoh, and Elspeth Graham. 2015. “Transnational Migration, Changing Care Arrangements and Left-Behind Children's Responses in South-East Asia.” Children's Geographies 13 (3): 263–277. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2015.972653.

- Jordan, Lucy P., and Elspeth Graham. 2012. “Resilience and Well-Being Among Children of Migrant Parents in South-East Asia.” Child Development 83 (5): 1672–1688. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01810.x.

- Mazzucato, Valentina. 2014. “Child Well-Being and Transnational Families.” In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, edited by A. Michalos, 749–755. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Mazzucato, Valentina. 2015. Mobility Trajectories of Young Lives: Life Chances of Transnational Youths in Global South and North (MO-TRAYL). Maastricht, The Netherlands: ERC Consolidator Grant No. 682982.

- Mazzucato, Valentina, Victor Cebotari, Angela Veale, Allen White, Marzia Grassi, and Jeanne Vivet. 2015. “International Parental Migration and the Psychological Well-Being of Children in Ghana, Nigeria, and Angola.” Social Science & Medicine 132: 215–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.058.

- Mazzucato, Valentina, and Djamila Schans. 2011. “Transnational Families and the Well-Being of Children: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges.” Journal of Marriage and Family 73 (4): 704–712. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00840.x.

- Mitrani, Victoria B., Daniel A. Santisteban, and Joan A. Muir. 2004. “Addressing Immigration-Related Separations in Hispanic Families with a Behavior-Problem Adolescent.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 74 (3): 219–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.74.3.219.

- OECD. 2017. “A Portrait of Family Migration in OECD Countries.” In International Migration Outlook 2017, 107–166. Paris: OECD publishing.

- Poeze, Miranda, and Valentina Mazzucato. 2014. “Ghanaian Children in Transnational Families: Understanding the Experiences of Left-Behind Children Through Local Parenting Norms.” In Transnational Families, Migration and the Circulation of Care, edited by L. Baldassar and L. Merla, 149–169. London: Routledge.

- Poeze, Miranda, and Valentina Mazzucato. 2016. “Transnational Mothers and the Law: Ghanaian Women’s Pathways to Family Reunion and Consequences for Family Life.” In Family Life in an Age of Migration and Mobility, edited by M. Kilkey and E. Palenga-Möllenbeck, 187–211. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Robertson, Shanthi, Anita Harris, and Loretta Baldassar. 2018. “Mobile Transitions: A Conceptual Framework for Researching a Generation on the Move.” Journal of Youth Studies 21 (2): 203–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2017.1362101.

- Sarolea, Sylvie, and Laura Merla. 2020. “Migrantes ou sédentaires : des familles ontologiquement différentes ?” In Faire et défaire les liens familiaux. Usages et pratiques du droit en contexte migratoire, edited by A. Fillod-Chabaud, and L. Odasso, 23–46. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Schapendonk, Joris, and Griet Steel. 2014. “Following Migrant Trajectories: The Im/Mobility of Sub-Saharan Africans en Route to the European Union.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104 (2): 262–270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2013.862135.

- Schapendonk, Joris, Ilse van Liempt, Inga Schwarz, and Griet Steel. 2018. “Re-routing Migration Geographies: Migrants, Trajectories and Mobility Regimes.” Geoforum 116: 211-216. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.06.007.

- Schapiro, Naomi A., Susan M. Kools, Sandra J. Weiss, and Claire D. Brindis. 2013. “Separation and Reunification: The Experiences of Adolescents Living in Transnational Families.” Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 43 (3): 48–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2012.12.001.

- Schmalzbauer, Leah. 2004. “Searching for Wages and Mothering from Afar: The Case of Honduran Transnational Families.” Journal of Marriage and Family 66 (5): 1317–1331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00095.x.

- Sheller, Mimi, and John Urry. 2006. “The New Mobilities Paradigm.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (2): 207–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a37268.

- Smith, Andrea, Richard N Lalonde, and Simone Johnson. 2004. “Serial Migration and its Implications for the Parent-Child Relationship: A Retrospective Analysis of the Experiences of the Children of Caribbean Immigrants.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 10 (2): 107–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.10.2.107.

- Strik, Martina Hermina Antonia, B. de Hart, and E. J. W. Nissen. 2013. Family Reunification. A Barrier or Facilitator of Integration? Nijmegen: Wolf Legal Publishers.

- Suárez-Orozco, Cerola, Irina L. G. Todorova, and Josephine Louie. 2002. “Making Up For Lost Time: The Experience of Separation and Reunification Among Immigrant Families.” Family Process 41 (4): 625–643. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.00625.x.

- van Geel, Joan, and Valentina Mazzucato. 2018. “Conceptualising Youth Mobility Trajectories: Thinking Beyond Conventional Categories.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (13): 2144–2162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1409107.

- Yarris, Kristin Elizabeth. 2017. “Sacrifice or Abandonment? Nicaraguan Grandmothers’ Narratives of Migration as Kin Work.” In Transnational Aging and Reconfigurations of Kin-Work, edited by P. Dossa and C. Coe, 61-62. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.