ABSTRACT

This study is a reaction to the paucity of research on children’s aesthetic encounters in living environments that are increasingly troubled by pollution, urban development and climate change. We ask how child-environment aesthetic encounters unfold in urban wilds and seek to identify the tensions and transformations that such encounters create. Our understanding of child-environment aesthetic encounters has been inspired by post-human and relational philosophies that allow us to delve into the transformational potentials of aesthetics. Drawing on ethnographic research through digital storying workshops in a Finnish primary school, we used an experiential-visual-textual method of rhizomatic patchworks for thinking with five children’s stories about aesthetic encounters in an urban forest. Through our inquiry, child-environment aesthetic encounters emerged as complex, discordant and dynamic intertwinements of adverse and pleasurable dimensions. In the children’s stories, sensuously rich encounters with matter, plants, animals, places, pollution and other humans encompassed shimmering and enchanting sensations. These aesthetically infused encounters in urban wilds affected the ways in which the children moved with and explored the environment. Our study broadens understanding of the aesthetic encounters through which children and the more-than-human world are mutually transformed, offering new insights for education to support children growing up in rapidly changing environments.

Introduction

Aesthetic and sensuous relating is vital for ecological sensitivity and care (Bennett Citation2001; Rose Citation2013; Rousell and Williams Citation2020). It is something valuable that needs to be explored, supported and treasured, as it holds the potential for finding more attentive and empathetic ways of living with non-human others (Bennett Citation2010; Kumpulainen et al. Citation2021; Merewether Citation2019; Rose Citation2013). Today’s children are confronted by unexpected and conflicting aesthetic qualities in their living environments due to pollution, climate change and rapid urban development (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020). These changes place growing demands on education to address the aesthetic dimensions of child-environment relations (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020; Rousell and Williams Citation2020). Although aesthetic and sensuous dimensions are inseparable from other aspects of life and lie at the heart of humans’ relationality with and understanding of the world (Berleant Citation2010; Malone Citation2019), education does not address aesthetics sufficiently and often disregards the aesthetic dimensions of children’s encounters with their environments (Rousell and Williams Citation2020).

For education to become more relevant to the everyday challenges of twenty-first century children and their ecological worlds, more attention needs to be paid to aesthetic perspectives and practices that recognize troubling, disturbing and ugly dimensions of environments, as well as those which are beautiful and delightful (Berleant Citation2010; Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020; Rousell and Williams Citation2020). Creating room for children to explore the aesthetic dimensions of their local environments in their complexity can benefit their well-being and promote their ecological sensitivity and care (Berleant Citation2010; Saari and Mullen Citation2020). However, there has been a paucity of research that considers aesthetics from more complex and dynamic perspectives and that recognizes both adverse and pleasurable aesthetic dimensions in child-environment relations.

In this study, we ask how child-environment aesthetic encounters unfold in urban wilds and seek to identify the tensions and transformations that such encounters create. By ‘urban wilds’, we refer to the human and more-than-human materialities, practices and agencies that urban environments comprise, as well as the lively, wild and often disharmonious ways that they encounter (Rose Citation2012; Van Dooren and Rose Citation2012). Our inquiry of child-environment aesthetic encounters has been inspired by Deborah Bird Rose’s definition of ‘encounters with shimmer’, based on the Australian Aboriginal Yolngu concept of bir’yun, which alludes to the shimmering and enchanting brilliance of becoming aware of the past, present and future of Earth’s transformation through multispecies relations (Malone et al. Citation2020; Rose Citation2017a). Rose first learned about shimmer in her encounters with northern Australian Aboriginal people and their dance and song with the earth (Rose Citation2017a). In need of ‘radically reworked forms of attention’ (55), Rose (Citation2017a) embraces this Aboriginal aesthetics in her work because it challenges Western notions of human exceptionalism and evokes sensations of being part of the lively multispecies processes that compose the world. In our inquiry we also draw on Jane Bennett’s (Citation2001, Citation2010) vital materialism, which strongly relates to Rose’s theorizing of shimmer, and allows us to delve into what happens aesthetically between bodies and materialities. However, we acknowledge and are mindful of our inquiry as situated in a Western Finnish context, with non-Indigenous children and researchers. Our interest in the concept of shimmer springs from a need to expand beyond the Western gaze and we argue that there is excellent value in broadening aesthetic discourse to include various philosophical perspectives, like synergies between relationally attuned post-human and Indigenous perspectives (Malone et al. Citation2020).

With an affective and material focus, relational thinking questions the dualistic and anthropocentric ideals of Western humanist aesthetics, shifting the focus from individuals and binaries towards collectives, hybrids and materialisms (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987; Hoogland Citation2014; Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020; Rousell and Williams Citation2020). Furthermore, relationally attuned approaches highlight the sensuous and embodied nature of human experience, understanding and action, revealing how sensoriality emerges through children’s relationality with environments and the more-than-human world (Bennett Citation2010; Malone Citation2016, Citation2019). Thus, we approach child-environment aesthetic encounters as sensuously saturated relationships between human and more-than-human agencies in which bodies and materialities are entwined and create transforming atmospheres. This approach opens possibilities for discerning the interlacing adverse and pleasurable dimensions of aesthetics and recognizes relationalities, complexities and tensions that often remain hidden from an anthropocentric view.

Our inquiry has its outset at the intersection of several ongoing threads. In this paper, we first discuss the threads of our theoretical framing of child-environment aesthetic encounters drawing on relational perspectives. We then describe our ethnographic fieldwork with second graders in a Finnish primary school, during which five children’s digital storying about the aesthetic dimensions of their neighborhood materialized as something captivating and tension-laden that inspired us to delve deeper into the aesthetic dimensions of child-environment relations. Then we discuss the processes of our inquiry through the visual and artistic method of ‘rhizomatic patchworks’ that developed as part of our work and intertwines the children’s stories with our (i.e. the researchers’) own explorations of environments, artistic practices and thinking through relational theories (Rousell et al. Citation2020; Sellers Citation2015). We present our findings through three rhizomatic patchworks stemming from the five children’s storying, understanding these patchworks as open-ended stories, which readers are invited to linger over and extend. We conclude with a discussion of how aesthetics might be conceptualized and practiced anew in education through relationally attuned perspectives. Thus, through processes of intertwining the children’s stories with relational aesthetic theories and methods, and our own explorations of environments, our inquiry responds to this Special Issues call for new conceptualizations of climate change and childhood (climatehood), by re-considering and re-imagining how children aesthetically relate within ecological worlds.

The shimmering fabric of child-environment aesthetic encounters

In our inquiry we delved into the shimmering fabric of child-environment aesthetic encounters through relational perspectives that move beyond conceptual dualisms and grasp the sensorial richness of more-than-human relations (Bennett Citation2010; Malone et al. Citation2020; Rose Citation2017a). Rose (Citation2017a) describes aesthetics through the Australian Aboriginal concept of shimmer, as ‘lures that both entice one’s attention and offer rewards’ (53) and explains how by evoking sensations and responses this shimmer makes us attentive to our materially enmeshed relationship with the more-than-human world. This thinking relates to Bennett’s (Citation2010) idea of humans as incorporated into the vital materiality that constitutes the world. Bennett refers to an ‘aesthetic-affective openness’, highlighting the importance of sensuous perception for ‘detecting (seeing, tasting, smelling, hearing, feeling) a fuller range of the nonhuman powers circulating around and within human bodies’ (11). These nonhuman powers can be understood as material agencies (Bennett Citation2010), which are also referred to in this study as aesthetic agencies. Aesthetic agencies are relationally emergent, which means that materialities and bodies, including children and environments, affect and are affected through their various assemblages (Bennett Citation2010). Moreover, relations in aesthetic encounters are temporally and spatially vast, and aesthetic agencies can shimmer and move across centuries, entwining materially multifaceted threads and traces in child-environment aesthetic encounters (Malone et al. Citation2020; Rose Citation2017a). Thus, thinking from relational perspectives captures the aesthetic agencies of matter and bodies, allowing us to explore how children and environments draw each other into aesthetically infused encounters and what such encounters can set in motion (Bennett Citation2010; Hickey-Moody Citation2013; Hoogland Citation2014). Drawing on these notions, we understand child-environment aesthetic encounters as creations of the interweaving movements of matter and space that communicate vitality and life.

Unlike the Western aesthetic tradition of defining beauty and ugliness as contradictory phenomena, relational thinking transcends binaries, inviting us to approach aesthetic dimensions as entwined attracting and repelling forces (Hoogland Citation2014; Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020). Hoogland (Citation2014) theorizes aesthetics from a non-representational perspective as follows:

The difference between the attractive and the repulsive, the beautiful and the sublime, is one of degree rather than kind. That is to say, it is a difference not so much in terms of an opposition as one originating in the degree of affective intensity that marks the occasion of highly differentiated aesthetic experiences–experiences that critically include a sense of beauty. (Hoogland Citation2014, 56)

The transformational power of aesthetics lies in this enmeshment of attraction and repulsion, as tensions and frictions between different degrees of affective intensities provoke movement (Hoogland Citation2014). Friction should be understood not as a negative force, but as an energy that produces reactions, thereby inspiring changes, transformations and shifts in motion (Pacini-Ketchabaw Citation2013; Tsing Citation2020). However, friction does point to the complex and inharmonious ways that materialities and energies often encounter. Thus, while aesthetic encounters are about movement and vitality, they have disorganizing and de-territorializing potentials (Hoogland Citation2014), and such transformations can set in motion both human care and violence (Rose Citation2017a). Hence, the idea of aesthetic agencies that have the power to affect through ongoing and intricate more-than-human encounters raises critical questions about care and responsibility in the present and future and challenges us to consider these questions in our understanding of child-environment aesthetic encounters.

It follows that child-environment aesthetic encounters involve wild configurations that challenge anthropocentric ideas of what is connected to whom and unsettle notions of care and responsibility as smooth and harmonious (Bennett Citation2010; Haraway Citation2016). Encountering shimmer and enchantment extends an invitation to form caring attachments with the more-than-human world (Bennett Citation2010; Rose Citation2017a). According to Bennett (Citation2010), more relationally attuned care can be set in motion through anthropomorphizing engagement, which means approaching non-human bodies and creatures as humanlike. This is close to Rose’s (Citation2013, Citation2017b) description of animistic thinking in Indigenous philosophies. From a post-human and relational perspective, anthropomorphism and animism imply a sensory and embodied openness and attentiveness to other bodies as agentic and related to oneself (Bennett Citation2010; Malone Citation2019; Rose Citation2013, Citation2017b). Bennett suggests that this kind of aesthetic relating can ‘uncover a whole world of resonances and resemblances’ (Citation2010, 99), promoting a sensuous attunement with and understanding of non-human and human lives as kinships, thus evoking care for the more-than-human world. These theories draw our attention to the possibilities that the unfolding of child-environment aesthetic encounters offer for children and environments to become entwined and transform in considerate and caring ways.

To conclude, aesthetic encounters can encompass multiple layers of aesthetic agencies and affective dynamics at play simultaneously, and we suggest that these complexities are significant for child-environment relations and need to be acknowledged and investigated. In this regard, relational philosophies invite us to move beyond notions of children and environments as separate or of the pleasurable and adverse as opposites and explore how they emerge, shimmer and transform as entwined and related to each other.

An inquiry into child-environment aesthetic encounters in urban wilds through storying

Our inquiry draws on ethnographic fieldwork in a Finnish primary school, where 62 children (aged 7–9 years) from four second-grade classes took part in two digital storying workshops to explore their local urban forest and neighborhood. The two workshops were part of a four-month-long project (autumn 2019 to early spring 2020) that combined environmental, literacy and arts education. The events of these workshops were part of the ongoing research of our Enriching Children’s Ecological Imagination (ECHOing) research group, which investigates children’s wonder, curiosity and learning related to topics of environmental relationalities, ecological challenges and climate change.

Storying, including storytelling and storycrafting, is an essential aspect of our collaboration with children. We understand storying events as emerging through sensuously infused encounters with the more-than-human world and involving experiencing, imagining and expressing across spaces, places and time (Byman et al. Citation2022; Kumpulainen et al. Citation2020; Renlund et al. Citation2022). Thus, storying events emerge as interlacing environments, actors, agencies and materials and create new meanings and worlds (Facer Citation2019; Haraway Citation2016; Kumpulainen Citation2022; Phillips and Bunda Citation2018). By inviting children to do research with us through storying we hope to give room to imaginative and multimodal ways of exploring, listening and creating that give value to children’s manifold aesthetic experiences and perspectives as part of world-making practices (Phillips and Bunda Citation2018; Van Dooren and Rose Citation2012).

In the storying workshops, we invited the children to listen to a story about forest elves before going outdoors to craft stories about the elves and the local forest with a novel augmented reality (AR) application called MyARJulle. During the storying events, we joined the children in exploring the urban wild, which involved the school playground’s various landscapes and interlacing richness of agencies, such as roads, traffic, humans, buildings, atmospheric conditions, woods, hills, grassy fields, rocks, streams and animals. The school building and playground have no clear boundaries or fences separating them from the neighborhood, which allowed us and the children to move freely in the landscape during the workshops. The children used the AR application to take photographs of the landscape and create imaginative narratives around these images. After exploring the school playground and adjacent forest, we invited the children to continue their storying in small groups by discussing their pictures and elaborating on the narratives around them. During these conversations we asked the children questions about their sensory experiences and emotions in relation to the local environment.

We used a range of methods to document the storying workshops, including video recording and later transcribing the outdoor explorations and group discussions. We also took notes of our thoughts and experiences during the workshop events. These documentation practices, rather than being representations, became part of the manifold stories that unfolded during the workshops and allowed us to become enchanted and transformed in various ways during the inquiry (Malone Citation2019). Our understanding of what are considered to be data is fluid, focusing on how sensuous experiences, events and ideas interconnect with each other and are mutually affected, rather than trying to separate certain practices or elements into constituent data (St. Pierre Citation1997).

In this study, we explored recordings, transcriptions and notes from storying events involving five children, Lisa, Mary, Silja, Mauno and Simon, because they ‘glowed’ and spoke to us in ways that left aesthetic traces in us and inspired our thinking (MacLure Citation2013). These child-led stories became primary in challenging our understanding of children, environments and aesthetics as our engagement with the children’s stories developed through an inquiry process that we call rhizomatic patchworks. It is an experimentative process through which various interlacing data (sensuous experiences, digital artwork, photographic images, videos, transcriptions, notes and theoretical ideas) are composed into assemblages that build from the children’s stories, allowing a creative experiential-visual-textual contemplation to form patchworks of new and meaningful interconnections (Rousell et al. Citation2020; Sellers Citation2015). In the following section, we describe this process in more detail.

Thinking and learning from children’s stories through rhizomatic patchworks

In encounters with art and stories, one can at times sense an unsettling nudge that reshapes one’s perception and understanding (Hoogland Citation2014). For instance, this can happen when uncanny combinations of familiar and strange elements are introduced (Hickey-Moody Citation2013). The storying of Lisa, Mary, Silja, Mauno and Simon had such an effect on the first author. They offered her relatable narratives while introducing new ways of approaching environments. Even before this paper took form, these stories had become part of the first author’s forest wanderings. She caught herself exploring the urban wild through the children’s words and expressions in various aesthetically new and unknown ways. These experiences extended to her artistic work, materializing as digital images and visual contemplations, resulting in the initial patches that later formed the three rhizomatic patchworks on child-environment aesthetic encounters in urban wilds.

The methodological approach that guides our thinking is inspired by Sellers’ (Citation2015) rhizomatic storyboard methodology, methods of a/r/tography (Irwin Citation2013; Irwin et al. Citation2006; Rousell et al. Citation2020) and Deleuze and Guattari’s (Citation1987) philosophical concept of rhizome. A rhizome is a heterogeneous and transforming assemblage of connections between diverse dimensions of reality in which points of the rhizome can be connected to anything and everything (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987). The rhizomatic method allowed us to approach the practices, processes and documentations of our inquiry through non-linear relations (Irwin Citation2013; Irwin et al. Citation2006).

While our inquiry developed through several intersecting threads and events, the creation of the rhizomatic patchworks included certain practices that, over time, became essential parts of the process. For instance, the video recordings from the workshops, the children’s stories and our own notes and experiences played a significant role in our thinking and creating. During our writing and visual creation processes, we frequently returned to the recordings, letting them affect our thinking and merge with the relational theories upon which we were meditating (Irwin Citation2013). Moreover, moved by the children’s stories, our rhizomatic paths brought us into forests and parks, sensing and thinking with matter and making our own sensuous experiences part of the rhizomatic patchworks (Irwin et al. Citation2006). This made us attentive to the ways in which adverse and pleasurable dimensions are entwined and become part of the unfolding of child-environment aesthetic encounters in urban wilds.

Another frequent practice was that of the first author sending the co-authors written provocations by digital means. These provocations contained theoretical concepts, parts of the children’s stories and challenging questions. The co-authors would then respond to the provocations with artwork, photographic images, words or thoughts, which were included by the first and third authors in the visual and textual creation of the patchworks using image editing software. All authors also frequently met online to think and work on the patchworks through co-writing and co-creating. This mixture of academic and art-making practices enriched and expanded our inquiry by incorporating embodied and sensory forms of knowing and thinking into the process, providing the aesthetic means necessary to multidimensionally engage with the tensions and transformations of child-environment aesthetic encounters (Heinrichs and Kagan Citation2019; Hoogland Citation2014). The various threads of rhizomatically seeking, encountering, sensing, absorbing, examining and creating helped us to explore the complexities and relationalities of aesthetic encounters, which are not conducive to easy answers, solutions or categories (Heinrichs and Kagan Citation2019; St. Pierre Citation1997).

Three patchworks of unfolding child-environment aesthetic encounters in urban wilds

In this section, we discuss three rhizomatic patchworks related to five children’s storying in the local urban wild. We explored how child-environment aesthetic encounters unfolded in urban wilds and what tensions and transformations such encounters created. In the patchworks that we created, child-environment aesthetic encounters took place amidst the flow of everyday events, such as walking to school, visiting grandparents and playing in the local forest. The patchwork stemming from Lisa’s storying about aesthetic encounters in a cherished forest clearing includes a tall spruce and a big rock, wonderful humidity and annoying sound pollution. In the patchwork emerging from Mary’s and Silja’s storying, sensuous relating to enchanting trees and plants is entwined with vexing encounters with garbage and suffering non-human others. In the patchwork springing from Simon’s and Mauno’s storying, abandoned things, material textures and ancient rocks in the forest mingle in ways that create encounters of shimmering danger.

Aesthetic encounters unfolding through a cherished forest clearing, humid atmospheres and annoying sound pollution

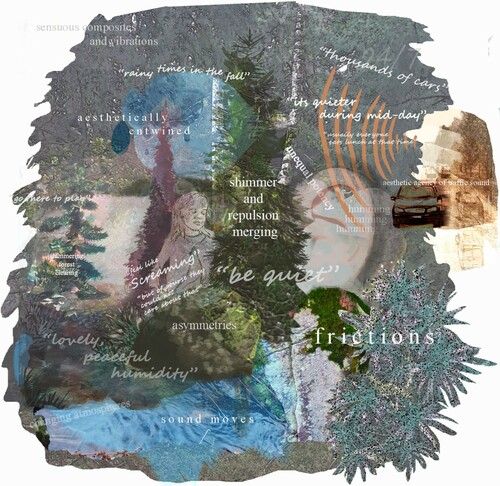

There is a discordant ambience of sensuous pleasure and annoying sound pollution in our patchwork arising from Lisa’s storying about her favorite place in the local forest (). Lisa described a tall spruce with wide branches under which she could hide and a big rock that she could climb to look around. This cherished place seemed to hold a shimmer for Lisa, and she would often go there to play, climb and hide. She also described a permeating lovely, peaceful humidity on rainy autumn days. However, the urban wild was not simply pleasing and peaceful. Obtrusive and repellent dimensions, such as traffic sounds, were entwined with its shimmering enchantment. At one point, Lisa explained that in her favorite place in the forest, behind a steep cliff, there was a constant hum from thousands of cars on a busy highway. At another point, she said, ‘Sometimes there aren’t that many cars, and it’s quieter. … I like going there sometimes on Saturdays and Sundays, sometimes at midday, because I trust there’s not so much noise … because everyone usually eats lunch at that time’.

Figure 1. A patchwork growing from Lisa’s storying of a shimmering forest clearing, humid atmospheres and annoying traffic sounds.

Through our patchwork (), we consider how the spruce, the rock, the traffic, Lisa and other inhabitants of this urban wild are aesthetically entwined, shifting and transforming with varying intensities through aesthetic encounters. We can sense how the sound from traffic, seemingly immaterial and disappearing, in fact has an aesthetic agency and is a vital part of the urban wild. As Dernikos et al. (Citation2020) note, sounds can be ‘sonorous flickers, gut punches, or complex mobilities’ (3). We imagine how, in Lisa’s story, the sound moves in humming waves from the highway across the steep cliff into the forest where she is playing. The vibrating sound is entwined and changes with the fibers of materials and bodies, becoming part of the aesthetic encounter and of Lisa’s and the forest’s reciprocal movements. Like everything else, the traffic sound itself is a multi-agential creation, born through assemblages of machines, road textures, cultural habits and political activity, to mention but a few agencies. Hence, the traffic sound’s mutual becoming with Lisa and the forest differs across temporalities and weather conditions, creating atmospheres that change according to the season, time of day and flux of different human and non-human bodies and materialities. Some sensuous composites in these unfolding aesthetic encounters enchant and attract Lisa, who moves to become part of them, while other vibrations arouse repulsion and retreat. In this way, Lisa’s responses are aesthetically transformed with the changing conditions of the place. This relates to Pacini-Ketchabaw’s (Citation2013) description of forests as nature-culture entanglements that are ever-changing and always contain frictions between human and more-than-human agencies.

Engaging with Lisa’s storying about the aesthetic power of traffic sounds further draws our attention to the asymmetries and power dynamics at play in the relations between different bodies and materialities (Taylor, Blaise, and Giugni Citation2013; see also Haraway Citation2016). We became aware of how the relational elements of aesthetic encounters can clash and be affected in different ways and with unequal potency (Nxumalo and Villanueva Citation2020). In her storying, Lisa explained that she would like to scream at the cars to be quiet but that it would be pointless because they would not care. In other words, this aesthetic encounter unfolds through the convergence of various aesthetic agencies that have different potentials to affect. How these potentials manifest depends on the encounters in which they engage (Bennett Citation2010). In the aesthetic encounter between Lisa, the forest and traffic sound, the aesthetic agency of traffic sound grows strong and repellent, affecting Lisa’s presence and sensations. However, the attractive agency of the humid atmosphere of the forest is also strong, calling on Lisa to move towards her favorite place. Thus, the shimmer of the forest clearing awakens through the merging of these attracting and repelling dimensions, not as opposites but as related intensities that, by coming together, cause tensions and have various potentials to move and transform (Bennett Citation2001; Hoogland Citation2014; Rose Citation2017a).

Aesthetic encounters unfolding through enchanting forests, sensuous relating, repulsive garbage and non-human suffering

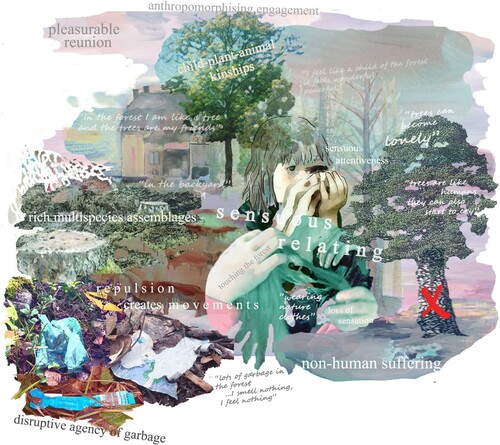

Inspired by Silja’s and Mary’s joint storying, the patchwork in considers enchanting forests, sensuous relating and the disruptive agency of garbage in child-environment aesthetic encounters. In a joint discussion, Silja and Mary described several occasions on which they felt connected to the forest, and trees, plants or bugs communicated something to them through movements and sounds. Silja recounted how the shift from an indoor environment to the forest inspired a pleasurable reunion with the forest through sensuous exploration and communication: ‘When I’ve been indoors, I feel wonderful in the back garden, and when I go to the forest, I like exploring everything there. I also like talking to the plants’. She explained that when she went to the forest near her grandmother’s house, she sometimes had a sense of becoming one with the forest, like ‘a child of the forest’, which felt wonderful. Mary also talked about touching the forest and said that she liked the flies flying around, making sounds with their wings, and landing on her head. She expressed a wish to be friends with the trees and to walk through the forest in ‘nature clothes’: ‘Sometimes I go to school wearing nature clothes so that when I go to the forest … I am also like a tree, and the trees are a bit like my friends’. Silja’s and Mary’s depictions remind us of the suggestion by Dernikos et al. (Citation2020) that bodies, materials and spaces can ‘extend into us and register in diverse, multisensory and multitemporal ways’ (7), which illustrates that the boundaries between bodies and materialities are diffuse and porose in the unfolding of child-environment aesthetic encounters. As Bennett (Citation2001) notes, the shimmer and allure of enchantment comes from the marvelous awareness of one’s enmeshment and mutual becoming with the world.

Figure 2. A patchwork growing from Mary’s and Silja’s storying of enchanting forests, sensuous relating, repulsive garbage and non-human suffering.

Through Silja’s and Mary’s storying, we imagine how the relational transformations of the urban wild can be sensuously apprehended within aesthetic encounters and how such encounters tell of aesthetically infused child-plant-animal kinships (Bennett Citation2001; Malone Citation2019; Rose Citation2013). In Mary’s and Silja’s stories, sensuous and embodied explorations with plants and animals aroused curiosity and attunement to the relationalities of human and more-than-human worlds (Nxumalo and Villanueva Citation2020). Thus, we consider how shimmering atmospheres in the urban wild enchant and extend an invitation to sensuously engage and metamorphose with matter and bodies of the forest, becoming a forest-child and emerging as something more than a forest and a child without losing either (Rose Citation2017a). We understand this ‘something more’ as an attunement to the multiple agencies and the rich multispecies assemblages that aesthetic encounters involve (Bennett Citation2001; Haraway Citation2016; Rose Citation2013).

However, as Haraway (Citation2016) remarks, ‘making kin’ is not a harmonious or innocent endeavor; it contains collisions and vulnerabilities. In Mary’s and Silja’s storying, aesthetic encounters in the urban wild unfolded through the entwining of pleasurable and sensuous relating to the horror of suffering non-human others and repulsive garbage. Silja vividly recounted how she encountered beetles with their insides gushing out, crushed by humans stepping on them, and how she moved them to a safe place, hoping to relieve their suffering. Mary mentioned seeing trees marked to be cut down. She reflected on how trees can become lonely when humans cut down forests and observed that trees need friends to grow. She also pondered how trees perceive garbage and said that she would like to tell everyone to stop throwing garbage in the forest because trees are like humans, and they can also cry. Mary further described how copious amounts of litter made her unable to smell or feel anything, and Silja expressed her worry that ‘the whole planet will be filled with garbage, and then it will not smell good’. We understand these unfolding aesthetic encounters in Silja’s and Mary’s storying as involving an anthropomorphizing engagement that evokes sensuous attentiveness to and care for non-human others and the more-than-human world (Bennett Citation2001, Citation2010; Rose Citation2013).

We can relate to Mary’s and Silja’s descriptions of garbage in the forest as aesthetically offensive and repellent. The site of plastic bottles, old candy wrappers, cigarette butts and other discarded things found amidst the thicket and undergrowth in forests can have a jarring effect, making us brutally aware of the provoking and engaging aesthetic agency of non-human matter. In their aesthetic encounters, Silja and Mary pick up trash from the forest: ‘Every time I see garbage somewhere, I find a garbage bin and throw it in there’. Hence, the coming together of pleasurable sensuous relating with repulsion and ugliness in the urban wild creates movements. The shimmering aesthetic dimensions of these encounters attract and repel in various ways, prompting Silja and Mary to become sensuously attuned to the forest while actively engaging as part of it by tugging, pushing and leaving traces in the transforming environment.

Aesthetic encounters unfolding through the shimmer of abandoned things, material textures and ancient rock formations

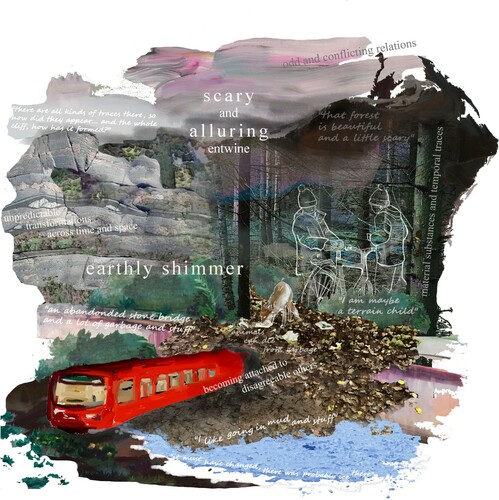

In the patchwork expanding from Simon’s and Mauno’s joint storying (), we consider child-environment aesthetic encounters through abandoned things, material textures, forest terrain and ancient rock formations, which mingle aesthetically in ways that create sensations of adventure, danger and beauty.

Figure 3. A patchwork growing from Simon’s and Mauno’s storying of the shimmer of abandoned things, material textures and ancient rock formations.

During the digital storying workshop, Simon and Mauno with a group of children found an abandoned bicycle in a small clearing surrounded by trees and high rocks. They seemed to be drawn in by this encounter and gathered around the bicycle’s severed parts, which were scattered around the forest bed. Simon and Mauno picked up, looked at, touched and played with the parts. In Simon’s and Mauno’s storying, abandoned things ‘shimmered’ and invited them to engage with ‘a vibrant and vibrating world’ that made them attentive and inspired them to create and imagine stories (Rose Citation2017a, 54). Simon described an ‘abandoned bridge’ over railway tracks and a forest that was both ‘beautiful and a little scary’. Mauno explained that he enjoyed places where he could hide and find abandoned things. During this discussion, Simon suggested a ‘very’ abandoned forest next to a hill where he and Mauno could go and play. He explained that many exciting things, like an old moped, an abandoned stone bridge and garbage could be found there.

While many would call abandoned things junk and pollution, in Simon’s and Mauno’s storying, they emerged as enchanting and offering opportunities for adventures and exploration. However, these aesthetic encounters were not free of tension and friction. Through the patchwork, Simon’s and Mauno’s narrations provoked eerie sensations in which scary and alluring dimensions were entwined. This made us attentive to how encounters with shimmer and enchantment in the urban wild can unfold through unexpected, odd and conflicting relations that catch children’s attention (Bennett Citation2010). To follow Molloy Murphy’s (Citation2020) thinking, this relates to ‘risking attachment to that which we have cast out’ (23). At one point during the storying, Simon mentioned that garbage can be bad for animals because they can choke on it. This brief moment of acknowledging the harms of garbage glimmered as a prickly, stinging piece in Simon’s and Mauno’s storying and reminded us of the challenges facing children in today’s ecological crisis, such as bewildering aesthetic encounters of becoming captivated by and attached to unwanted and disagreeable others (Instone Citation2015; Molloy Murphy Citation2020). Although these disagreeable others can be dangerous, repulsive and harmful, they can simultaneously enchant and inspire, which illustrates the multiple agentic potentials of bodies and matter to move and transform in unpredictable ways in child-environment aesthetic encounters.

Material substances and temporal traces in the urban wild were additional topics that stimulated animated discussions with Simon and Mauno. When asked whether he felt like a nature child, Simon responded that he did not see himself as a nature child because he liked playing with mud and dirt; instead, he called himself ‘a terrain child’. He explained that he liked riding his mountain bike in the forest with his friends. Mauno, in turn, said that he loved the peacefulness and all the sounds in his local forest and that he especially enjoyed climbing high cliffs and rocks with steep walls. He described the formations and patterns that he had seen on the cliffs in a special place where he often played and wondered what might have created them. He went on to reflect on how the whole cliff might have come into being and what had been there before the cliff. He was sure that the cliff must have changed over time and suggested that ‘it could be millions of years old’ and that ice might have helped to transform it. To us, Simon’s and Mauno’s sensuous engagement with textures and material surfaces is related to being aesthetically attuned to the shimmering, lively and transforming materialities of the urban wild, which involves recognizing aesthetic agencies across space and time (Molloy Murphy Citation2021; Rose Citation2017a). Thus, the unfolding of child-environment aesthetic encounters in urban wilds encompasses the coming together of generations of aesthetic agencies and ‘earthly shimmer’ (Malone et al. Citation2020; Rose Citation2017a). This challenges ideas of children relating to local landscapes as isolated occasions of engaging with specific aspects or characteristics and calls for holistic, aesthetic and embodied pedagogical approaches with a focus on the complex in-betweens involved in child-environment relations (Kumpulainen et al. Citation2021; Malone et al. Citation2020; Renlund et al. Citation2022).

Stitching the patchworks together and threading new pieces

By investigating children’s aesthetic encounters with urban wilds, our inquiry addresses the increasing demands placed on educational research and practice to consider the aesthetic tensions that children experience in their living environments due to ecological transformations (Rousell and Williams Citation2020). Thinking with five children’s storying in their local urban forest through the method of rhizomatic patchworks, we learned how child-environment aesthetic encounters in urban wilds emerged as complex, discordant and dynamic. In the children’s stories, a variety of sensuously rich encounters with matter, plants, animals, places, pollution and other humans created entwinements of both appeal and repulsion. Furthermore, the children’s actions were aesthetically entwined with these discordant and transforming encounters, affecting the ways in which they moved with and explored the environment.

As with the children’s storying, our patchworks do not create smooth and harmonious arrangements. Rather, they point to the differences and asymmetries in the unfolding of aesthetic encounters in child-environment relations, where bodies, materialities and atmospheres interweave both agreeingly and discordantly. However, part of the shimmer and enchantment lies in the jagged edges. These strange, uncomfortable tensions captivated us and challenged our thinking, compelling us to reconsider and reimagine aesthetics in education. Thinking from relational perspectives scrambled notions of appealing and adverse aesthetics and allowed us to recognize shimmer and enchantment as entwined dimensions of pleasure and repulsion. This approach revealed frictional engagements, sensuous attentiveness and care for transforming materialities and bodies, as well as bewildering encounters of becoming captivated by disagreeable others. These findings are important for understanding how children shape and are shaped as agents participating in various tension-laden encounters in urban wilds. For education to become responsive to children’s actual lives, and what this Special Issue frames as climatehood, we need to broaden the definition and understanding of what aesthetic encounters include and to become more attentive to the manifold sources of shimmer and enchantment in urban landscapes. Children encounter pleasure, beauty, belonging, repulsion, horror and worry within frictional assemblages and in the complexity of this world, not in isolated parts of it (Bennett Citation2001). One of the challenges faced by today’s children is to simultaneously embrace, become captivated and form attachments with this world while exploring it critically and imagining new and better ways to transform and relate with non-human others and altering more-than-human landscapes (Instone Citation2015; Rousell and Williams Citation2020).

Nxumalo and Villanueva (Citation2020) emphasize the importance of acknowledging the pedagogical potential of small ‘shifts toward relational practices’ for learning to live in changing and ecologically threatened environments. In a similar vein, there are initiatives in pedagogical development to draw inspiration from the more relational and non-binary relationship with the more-than-human world prevalent in Indigenous cultures (Dernikos et al. Citation2020; Rousell and Williams Citation2020) and old nature myths (Sintonen Citation2020). Such philosophies raise questions about human/nature relationships and challenge the anthropocentric practice of drawing boundaries between species and environments. Following Rose (Citation2013, Citation2017b), we suggest that child-environment encounters the world over hold aesthetically entwined relationalities across wild configurations of various kinds of matter, such as animals, plants, humans and pollution, and that significant dimensions of these encounters can be recognized through thinking from relationally attuned posthuman and Indigenous perspectives. Moreover, sensuous and embodied attentiveness to encounters with ‘lively matter’ can make the aesthetic agencies of non-human others more tangible and recognizable to children, potentially advocating environmental care and responsibility (Bennett Citation2001, Citation2010; Rose Citation2013). Thus, there is a call for education to learn from these ongoing child-environment relations and to acknowledge the value of embracing aesthetic practices from diverse cultures and philosophies (Merewether Citation2019; Nxumalo and Villanueva Citation2020; Rousell and Williams Citation2020).

To conclude, our inquiry offers new insights that can inform and transform education to support children growing up in rapidly changing ecological circumstances. By considering the aesthetics of child-environment relations from post-human and relational perspectives, pedagogical practices can recognize the multiple ways in which aesthetic dimensions affect the mutual transformations of children and environments (Malone Citation2016, Citation2019; Pacini-Ketchabaw Citation2013). Our findings suggest that giving space and value to children’s diverse aesthetic encounters with local environments and embracing both adverse and pleasurable dimensions can offer fruitful avenues for shared reflection about human and more-than-human relations and agencies. This is in line with Saari and Mullen (Citation2020), who argue that pedagogies that include opportunities to explore pollution and the adverse dimensions of places bear significance for promoting ecological engagement. Lastly, by being attentive to the tensions and frictions involved in children’s aesthetic encounters with environments, educators can better support children’s sense of uncertainty and bewilderment arising from these encounters.

Ethics approval statement

This study follows the ethical standards of the Finnish Advisory Board on Research on Integrity (https://www.tenk.fi) and was reviewed and approved by the Education Division of the City of Helsinki (HEL 2019-008574 T 13 02 01). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the children’s guardians. Pseudonyms have been used for all participants in this study.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the children and adults who took part in this study and shared their experiences, thoughts and stories with us. We would also like to thank researchers Laura Hytönen and Noora Oksa for their contribution to the data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bennett, Jane. 2001. The Enchantment of Modern Life: Attachments, Crossings, and Ethics. Oxford: Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691088136/the-enchantment-of-modern-life.

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NY: Duke University Press.

- Berleant, Arnold. 2010. Sensibility and Sense: The Aesthetic Transformation of the Human World. Exeter: Imprint Academic.

- Byman, Jenny, Kristiina Kumpulainen, Chin-Chin Wong, and Jenny Renlund. 2022. “Children’s Emotional Experiences in and about Nature across Temporal-Spatial Entanglements During Digital Storying.” Literacy 56 (1): 18–28. doi:10.1111/lit.12265.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dernikos, Bessie P., Nancy Lesko, Stephanie D. McCall, and Alyssa D. Niccolini. 2020. “Feeling Education.” In Mapping the Affective Turn in Education: Theory, Research, and Pedagogies, edited by Bessie P. Dernikos, Nancy Lesko, Stephanie D. McCall, and Alyssa D. Niccolini, 3–27. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003004219.

- Facer, Keri. 2019. “Storytelling in Troubled Times: What Is the Role for Educators in the Deep Crises of the 21st Century?” Literacy 53 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/lit.12176.

- Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press. https://www.dukeupress.edu/staying-with-the-trouble.

- Heinrichs, Harald, and Sacha Kagan. 2019. “Artful and Sensory Sustainability Science: Exploring Novel Methodological Perspectives.” Revista de Gestão Ambiental e Sustentabilidade 8 (3): 431–442. doi:10.5585/GEAS.v8i3.15734.

- Hickey-Moody, Anna. 2013. “Affect as Method: Feelings, Aesthetics and Affective Pedagogy.” In Deleuze and Research Methodologies, edited by Rebecca Coleman, and Jessica Ringrose, 79–95. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-deleuze-and-research-methodologies.html.

- Hoogland, Renée C. 2014. A Violent Embrace: Art and Aesthetics after Representation. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press.

- Instone, Lesley. 2015. “Risking Attachment in the Anthropocene.” In Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene, edited by Katherine Gibson, Deborah Bird Rose, and Ruth Fincher, 29–36. Brooklyn: Punctum Books. doi:10.21983/P3.0100.1.00.

- Irwin, Rita L. 2013. “Becoming A/r/tography.” Studies in Art Education 54 (3): 198–215. doi:10.1080/00393541.2013.11518894.

- Irwin, Rita L., Ruth Beer, Stephanie Springgay, Kit Grauer, Gu Xiong, and Barbara Bickel. 2006. “The Rhizomatic Relations of A/r/tography.” Studies in Art Education 48 (1): 70–88. doi:10.1080/00393541.2006.11650500.

- Kumpulainen, Kristiina. 2022. “Bridging Dichotomies Between Children, Nature and Digital Technologies.” In Nordic Childhoods in the Digital Age: Insights Into Contemporary Research on Communication, edited by Kristiina Kumpulainen, Anu Kajamaa, Ola Erstad, Åsa Mäkitalo, Kristen Drotner, and Solveig Jakobsdottir. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003145257.

- Kumpulainen, Kristiina, Jenny Byman, Jenny Renlund, and Chin-Chin Wong. 2020. “Children’s Augmented Storying in, with and for Nature.” Education Sciences 10 (6): 149. doi:10.3390/educsci10060149.

- Kumpulainen, Kristiina, Jenny Renlund, Jenny Byman, and Chin-Chin Wong. 2021. “Empathetic Encounters of Children’s Augmented Storying Across the Human and More-Than-Human Worlds.” International Studies in Sociology of Education, 1–23. doi:10.1080/09620214.2021.1916400.

- MacLure, Maggie. 2013. “Researching Without Representation? Language and Materiality in Post-qualitative Methodology.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (6): 658–667. doi:10.1080/09518398.2013.788755.

- Malone, Karen. 2016. “Reconsidering Children’s Encounters with Nature and Place Using Posthumanism.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 32 (1): 42–56. doi:10.1017/aee.2015.48.

- Malone, Karen. 2019. “Worlding with Kin.” Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy 4 (1): 69–80. doi:10.1163/23644583-00401011.

- Malone, Karen, Marianne Logan, Lisa Siegel, Julie Regalado, and Bronwen Wade-Leeuwen. 2020. “Shimmering with Deborah Rose: Posthuman Theory-Making with Feminist Ecophilosophers and Social Ecologists.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 36 (2): 129–145. doi:10.1017/aee.2020.23.

- Merewether, Jane. 2019. “Listening with Young Children: Enchanted Animism of Trees, Rocks, Clouds (and Other Things).” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 27 (2): 233–250. doi:10.1080/14681366.2018.1460617.

- Molloy Murphy, Angela. 2020. “Plastic City: A Small-Scale Experiment for Disrupting Normative Borders.” eceLINK Peer Reviewed Collection 4 (1): 21–34. https://angelamolloymurphy.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/plastic-city-a-small-scale-experiment-for-disrupting-normative-borders.pdf.

- Molloy Murphy, Angela. 2021. “The Grass is Moving but There is No Wind: Common Worlding with Elf/Child Relations.” Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy 18 (2): 134–153. doi:10.1080/15505170.2021.1911890.

- Nxumalo, Fikile, and Marleen Tepevolotl Villanueva. 2020. “(Re)storying Water: Decolonial Pedagogies of Relational Affect with Young Children.” In Mapping the Affective Turn in Education: Theory, Research, and Pedagogies, edited by Bessie P. Dernikos, Nancy Lesko, Stephanie D. McCall, and Alyssa D. Niccolini, 209–228. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003004219.

- Pacini-Ketchabaw, Veronica. 2013. “Frictions in Forest Pedagogies: Common Worlds in Settler Colonial Spaces.” Global Studies of Childhood 3 (4): 355–365. doi:10.2304/gsch.2013.3.4.355.

- Phillips, Louise, and Tracey Bunda. 2018. Research Through, With and as Storying. Oxon, New York: Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9781315109190.

- Renlund, Jenny, Kristiina Kumpulainen, Jenny Byman, and Chin-Chin Wong. 2022. “‘I Could Smell the Sound of Winter’: Children’s Aesthetic Experiences in the Local Forest Through Digital Storying.” In Nordic Childhoods in the Digital Age: Insights Into Contemporary Research on Communication, edited by Kristiina Kumpulainen, Anu Kajamaa, Ola Erstad, Åsa Mäkitalo, Kristen Drotner, and Solveig Jakobsdottir. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003145257.

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2012. “Why I Don’t Speak of Wilderness.” EarthSong Journal: Perspectives in Ecology, Spirituality and Education 2 (4): 9–11.

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2013. “Val Plumwood’s Philosophical Animism: Attentive Interactions in the Sentient World.” Environmental Humanities 3 (1): 93–109. doi:10.1215/22011919-3611248.

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2017a. “Shimmer: When All You Love Is Being Trashed.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, edited by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Heather Anne Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, 51–63. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/arts-of-living-on-a-damaged-planet.

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2017b. “Connectivity Thinking, Animism, and the Pursuit of Liveliness.” Educational Theory 67 (4): 491–508. doi:10.1111/edth.12260.

- Rousell, David, and Amy Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles. 2020. “Uncommon Worlds: Toward an Ecological Aesthetics of Childhood in the Anthropocene.” In Research Handbook on Childhood Nature: Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research, edited by Amy Cutter-MacKenzie-Knowles, Karen Malone, and Elisabeth Barratt Hacking, 1657–1679. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-67286-1.

- Rousell, David, Alexandra Lasczik, Peter J. Cook, and Rita L. Irwin. 2020. “Propositions for an Environmental Arts Pedagogy: A/r/Tographic Experimentations with Movement and Materiality.” In Research Handbook on Childhood Nature: Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research, edited by Amy Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Karen Malone, and Elisabeth Barratt Hacking, 1815–1843. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-67286-1.

- Rousell, David, and Dilafruz Williams. 2020. “Ecological Aesthetics: New Spaces, Directions, and Potentials.” In Research Handbook on Childhood Nature: Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research, edited by Amy Cutter-MacKenzie-Knowles, Karen Malone, and Elisabeth Barratt Hacking, 1603–1618. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-67286-1.

- Saari, Antti, and John Mullen. 2020. “Dark Places: Environmental Education Research in a World of Hyperobjects.” Environmental Education Research 26 (9–10): 1466–1478. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1522618.

- Sellers, Marg. 2015. “ … Working with (a) Rhizoanalysis … and … Working (with) a Rhizoanalysis.” Complicity 12 (1): 6–31. doi:10.29173/cmplct23166.

- Sintonen, Sara. 2020. “Bringing Mythical Forests to Life in Early Childhood Education.” International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 7 (3): 62–70. https://naturalstart.org/research/ijecee/volume-7-number-3.

- St. Pierre, Elizabeth Adams. 1997. “Methodology in the Fold and the Irruption of Transgressive Data.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 10 (2): 175–189. doi:10.1080/095183997237278.

- Taylor, Affrica, Mindy Blaise, and Miriam Giugni. 2013. “Haraway’s ‘Bag Lady Storytelling’: Relocating Childhood and Learning Within a ‘Post-human Landscape’.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 34 (1): 48–62. doi:10.1080/01596306.2012.698863.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2020. “Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection.” In The Environment in Anthropology, 2nd ed., edited by Nora Haenn, Allison Harnish, and Richard Wilk, 241–244. New York: New York University Press. https://nyupress.org/9781479876761/the-environment-in-anthropology-second-edition/.

- Van Dooren, Thom, and Deborah Bird Rose. 2012. “Storied-Places in a Multispecies City.” Humanimalia 3 (2): 1–27. doi:10.52537/humanimalia.10046.