ABSTRACT

This article weaves together a series of encounters between young children, trees, and mycelium within the multispecies worlds of Birrarung Marr, an ancient Aboriginal meeting place in the city of Naarm/Melbourne, Australia. Using creative ethnographic methods, it focuses on children’s involvement in an immersive theatre-making project exploring the intricate subterranean networks of communication and care between She-Oak trees and rhizo-mycelial networks in the local area. Weaving ethnographic description and careful engagements with Indigenous philosophies, the concept of pluriversality is evoked to consider how multispecies worlds are variously assembled, stolen, sustained, exhausted, regenerated, and interwoven along Birrarung Marr. Disrupting Western developmental models of childhood, the article argues that children’s animistic understandings of multispecies relations can inform responses to climate change which are sensitive to the intricate dependency relations that sustain life.

Introduction

All stories begin with Country. And as climate change reveals, all stories will end with Country, too. (Saunders Citation2021, 23)

When the city of Melbourne was founded by British colonisers in the nineteenth century they flattened Birrarung. The bends of the waterway were straightened, and the waterfall erased from existence. By flattening the differential between salty and fresh water the colonisers made it impossible to draw drinking water from the river. And yet this clearing of worlds has never been totalising or permanent. Stepping down onto Birrarung Marr today, you encounter a number of large ‘ancestor stones’ leading to a mound campsite, or ‘puulwuurn’, with intricate carvings also indicating an ‘eel walk’ which snakes along between the rocks. Along with a series of traditional shields, water vessels, and an audio installation, these elements form Birrarung Wilam (or ‘Common Ground’), a public installation artwork by Indigenous artists Vicki Couzens, Lee Darroch, and Treahna Hamm. Here you also find a lone building, a Victorian era tram repair station now converted to house a creative multi-arts studio for children. You approach a large, bright orange door as the unmistakable sounds of children’s cries and laughter fill the air. To your right a steep hillside rises, and just beyond that, a grove of she-oak trees dances feathery shadows across the ochre red ground.

World crossings at Birrarung Marr

This article weaves together ethnographic stories with speculative theorisations of children’s animistic encounters with multispecies worlds along Birrarung Marr. For the past two years I have been a resident researcher in the New Ideas Lab at ArtPlay along the banks of the Birrarung. The New Ideas Lab offers an experimental space for developing new artistic work for and with children as collaborators in the creative process. Between 2020–2021 a series of four works were commissioned by the City of Melbourne to specifically address children’s experiences and understandings of climate change. As a resident researcher, I have been situated in the midst of these collaborative processes as the works developed from the initial ‘dreaming stage’, through a series of making processes, to the final showing of works through immersive installations and performative events. This article focuses on the initial dreaming stages of Wood Wide Web, an immersive theatre-making project exploring subterranean networks of animate care and communication running through a small grove of She-Oak trees behind the ArtPlay building. I track how this project dynamically mutates and evolves as children sense and interact with an iterative series of immersive environments, weaving light, darkness, sound, space, colour, and movement into complex encounters with trees, mycelium, and their complex subterranean relations. This leads to a consideration of children’s tendencies to attribute animate qualities to animals, plants, and other nonhuman elements of their environments, and how children’s animism expresses an acknowledgement of mutual interdependence and relationality which is shared with many Indigenous wisdom traditions and knowledge systems.

As a North American migrant to Australia of mixed European Jewish heritage, I am but a passing visitor on lands which have been stolen from Aboriginal peoples and forcibly held by colonisers for over two centuries. I come from many generations of migrant peoples, and as a migrant artist and researcher I often find myself drifting between worlds with no claim to a homeland or national identity. My own knowledge of Country is limited to what the Gay-Wu Group of Women (Citation2019, xxvi) describe as the ‘very top layer … [of] open, public understandings’ that have been generously shared by Indigenous peoples. There are many other layers of language and knowledge to which I have no access or authority to speak of. For my research along Birrarung Marr this has meant finding ways of attending to the edges between Indigenous and non-Indigenous ways of knowing without simplifying or reducing their differences to one another. It has meant reading and thinking carefully with the works of Indigenous scholars both local (Briggs Citation2008; Saunders Citation2021) and further afield (Bawaka Country Citation2015; Citation2016; Citation2020; Cajete Citation2006; Kopenawa and Albert Citation2013), and considering these works alongside anthropological accounts of Indigenous ontologies and worldmaking practices often written by non-Indigenous scholars (Descola Citation1996; Povinelli Citation2016; Rose Citation2011; Viveiros de Castro Citation2005). In what follows, I place these accounts of Indigenous knowledges and worldmaking practices into conversation with ecological studies of subterranean worlds and interspecies communication networks (Beiler et al. Citation2010), and explore how these intersect with the speculative, animistic worlds inhabited by children and artists at ArtPlay.

Pluriversality

The ‘pluriverse’ is engaged throughout this article as prismatic concept for sensing the intricacy of worldmaking practices that gather around ArtPlay and the surrounding area of Birrarung Marr. Just as the Birrarung continues to be a place of crossings between worlds, this article also takes a pluriversal approach to weaving different experiences, stories, and philosophical orientations. Initially arising from First Nations peoples in Latin America, the pluriverse has gained currency in recent years as a concept of ontological pluralism which refuses the universalising language of humanism (Blaser and de la Cadena Citation2018; Castillo Citation2016; Escobar Citation2018), or what Law (Citation2015) describes as the western myth of ‘a single all-encompassing reality’ (127). As a powerful counter-concept to the monolithic universalisation of experience under late capitalism, the term ‘pluriverse’ has been linked to the work of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation which has maintained territory in open rebellion against the Mexican state since 1994. In the epitaph for their recent edited collection A World of Many Worlds, Mario Blaser and Marisol de la Cadena offer their own translation of the Zapatista movement’s ‘Fourth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle’:

In the world of the powerful there is room only for the big and their helpers. In the world we want, everybody fits. The world we want is a world in which many worlds fit. (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, cited in Blaser and de la Cadena Citation2018, 1)

Let’s listen. Do you hear the wind in the trees? The water on the beach? The splash of the fish? That is the wind, the trees, the water, the sand, the fish communicating. They have their own language, their own Law. Sometimes they are sending a message to humans. Sometimes they are sending a message to each other. Humans are not the centre of the universe, you see. Humans are only one part of it. Humans are part of Country along with the mullet, the tides, the moon, the songs and stories, along with the spirits, the plants and animals, the feelings and dreams. (Bawaka Country 2015, 273)

While Indigenous concepts of pluriversality effectively disrupt the universalising and anthropocentric aspirations of western humanism, they also find significant resonances with the aberrant movements of process philosophy, posthumanisim, and the new materialisms which continue to problematise and transform the underlying assumptions of western thought (cf Cole and Somerville Citation2017; Rosiek, Snyder, and Pratt Citation2020; Rousell Citation2022). Whitehead’s (1929/Citation1978) Process and Reality, for instance, can be read as a systematic attempt to establish a speculative empirical ‘route’ into the pluriverse within western philosophy. Whitehead’s pluriverse simultaneously invokes an open totality and a teeming multiplicity of actual worlds, each entirely real from the perspective of its own trajectory of becoming. This echoes the ‘perspectivism’ of both Aboriginal and Amerindian ontologies, which similarly attribute a singular and intensive ‘deixis’ to all things (Viveros de Castro Citation2005). In both cases, we encounter a wild plurality of perspectives which express the one through the many (pluralism), and the many through the one (monism). Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987, 20) once described this as ‘the magic formula we all seek – PLURALISM=MONISM’. Indigenous and non-Indigenous process philosophies may have very different concepts and practices for achieving the integration of monism and pluralism, but in many cases, they share a commitment to ontological multiplicity and the acknowledgement of an agentic perspectivism beyond the human (Rosiek, Snyder, and Pratt Citation2020).

Weaving worlds

You pass through ArtPlay’s orange doorway into a small atrium. Doors to the left of the front desk have opened to reveal a rectangular gallery space, which in turn has pivoted its walls onto a much larger, vaulted performance space. White moveable panels have been positioned to divide the performance space into tangential compartments. Multi-channel LED floor lights project a chromatic spray of rippling shadows onto the mobile walls, diffracting with the white light of analogue over-head projectors. The ambient sounds of organic-electronic synthesiser music are intermixing with bird calls. Three artists move around this space purposefully, projecting a deep focus but also a somewhat furtive aspect. Their aprons bear the insignia of their theatre company, a slightly addled but playful looking spider. The artists appear to be spinning a web of light, colour, movement, and sound.

Persephone, one of the company’s lead artists, stops to greet me as I wander around the space. She explains that they are creating a work called ‘Wood Wide Web’, and that they are trying to craft an ‘underground world’ which invites children to experience the subterranean interactions between trees and mycelium networks in the local area. She says this is a place of learning for their artistic team, that they are collectively developing their creative ideas in collaboration with young children, and that this entire undertaking is of an experimental nature. Another artist is adjusting the chromatics of the LED lights, and then manipulating a transparent drawing on the overhead projector. The projected image dances on the surface of the mobile wall: the seeds of a she-oak tree from the nearby grove, intermixing with the silhouettes of flowers collected just outside the door.

Wood wide web

Forest ecologist Suzanne Simard is widely acknowledged for establishing the first western scientific evidence demonstrating how trees communicate and care for one another through subterranean and airborn chemical signals (Beiler et al. Citation2010). Despite her work being ridiculed and dismissed by a male-dominated field in the 1990s, there is now widespread scientific acknowledgement that ‘trees recognise their offspring and nurture them and that lessons learned from past experiences can be transmitted from old trees to young ones’ (Hooper Citation2021, 40). Simard’s phrase ‘wood wide web’ has since entered into global circulation as a popular description of how trees exchange complex information through subterranean mycelium networks (e.g. akin to internet cables) and aerosols (e.g. akin to WiFi). These popular scientific descriptions of how forest communities converse, protect, and care for one another have also been disseminated through award-winning novels (Powers Citation2018), news articles (Macfarlane Citation2016), and children’s literature (Wild et al. Citation2020) in recent years. While such insights are celebrated for expanding public perceptions of forest communities as sentient and caring societies, they potentially occlude longstanding Indigenous sciences and knowledge practices which consider plants as animate and signifiying agents within more-than-human kinship relations (Bawaka Country Citation2022; Kohn Citation2013; Lewis et al. Citation2018; Hernández et al. Citation2021).

When trees are prevented from holding onto each other under the ground they get sick. Sick trees will recover and thrive if they are given a community to hold onto. When trees are ripped from soil and planted somewhere new, they won’t thrive unless they are connected as a community. Like entering new communities, there must be a grafting onto existing life ways, rooted in Country. (Saunders Citation2021, 31)

Cajete argues that the cultivation and expression of Indigenous sciences relies on knowledge gained through experience, finely tuned affective sensitivities, intuitive insights, and transgenerational teachings that gather, refine, and relay ecological knowledge practices across time and space. Crystal Arnold, a Gundungurra scholar of the Yuin nation in Southeast NSW, narrates her own experience of learning to converse with a family of She-Oak trees through a series of ‘yarns’ with Yuin cultural knowledge holders and Yuin Country itself. ‘Yarning’ is an Aboriginal English term used to describe spiralling, open-ended conversations of knowledge co-creation and sharing which often include more-than-human actors and agencies as active contributors and interlocutors. Wondering how to begin the process of yarning with trees, Arnold places her hand on the dark trunk of a She-Oak and asks directly if the tree would like to have a yarn with her.

After asking this question, Crystal felt her answer: ‘yes’. Messages then started to arise from all places; the way this tree grew and the song she shared through her leaves … Crystal also noticed an older tree nearby, a Grandfather tree who was taking care of the community by passing up the water to the younger ones. This grandfather tree was not only taking care of the younger trees and their wellbeing, but also his own wellbeing, by being an active member in his community. (Arnold, Atchison, and McKnight Citation2021, 139)

Fielding encounters

Adults and children begin to emerge sporadically through the doors of ArtPlay. Mostly mothers, a grandmother, also several fathers. The children are pre-school age, maybe 3 or 4 years old. The carers and children all seem to arrive pleasantly exasperated, constantly moving, tending, provoking, grappling, reacting to one another. They check in at the front desk, precariously balancing prams, drinks, snacks, dolls, a baby, mobile phones, and now clip boards, pens, forms to fill out. The parents and carers flop on the floor of the gallery space while the children alternate between climbing all over them and moving sporadically around the room. One of the production assistants in the New Ideas Lab welcomes the families and offers an acknowledgement of Country, paying respect to Aboriginal Elders past, present, or emerging who might be present. He explains that we are meeting on the stolen land of the Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung peoples of the Eastern Kulin Nation, and that Aboriginal sovereignty of this Country was never ceded. Mushrooms bloom in slow motion behind him on the projection wall. Persephone then crawls into the circle. Turning to face the squirming array of parents and children, she explains that we are going to explore how trees communicate and care for each other through mushrooms that live underground. She says ‘it’s just like the internet, but for trees. If one tree senses danger or that another tree nearby isn’t getting enough food, it can pass that message on through the mushroom network, and they can work together to help’. Nearly all the children are looking at something other than Persephone. One child’s attention shifts sporadically from her parent’s lap to her accompanying comfort toy, then ricochets off the wall, to an oblique corner, then back down to the floor. Suddenly she glances up and her eyes meet mine in a wide-eyed, inscrutable stare: Who are you? What are you doing here? I meet her stare with a quiet smile, and then our eyes both return to the mushrooms blooming in stop-motion on gallery wall.

Children of the pluriverse

Listening to Indigenous accounts of reciprocal relationships offers important opportunities for learning to sense and respond to environmental crisis in ways that respect the more-than-human relationality of local places. Childhood researchers Jenny Ritchie and Louise Gwenneth Phillips (Citation2021) warn that ‘the hegemonic externalising of "nature" by the anthropocentric, humanist western paradigm’ obscures the interconnectedness of more-than-human worlds, as well as the complicity of human agency in climate change and other world-ending events (3). Drawing on decades of experience working with Indigenous communities in early childhood contexts, Ritchie and Phillips propose listening to Indigenous knowledges as a way forward for intergenerational action on climate justice issues. They show how a recuperation of children’s agency in the face of climate change can be drawn from Maori, Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander wisdom traditions, each of which embed children within pluriversal kinship systems that respect, nurture, and value multispecies contributions to cultural life from a very young age.

Ritchie and Phillips suggest that a key difference between Indigenous and western understandings of childhood is that Indigenous communities value multispecies collectives as ‘the predominate unit of being’, rather than the individual human subject. Children are valued for their agency and contribution within ecological collectivities which also hold complex metaphysical significance. For instance, Māori values of relationality include children as powerful caretakers of spiritual energy or ‘mana’ held by the land and all that inhabit it.

The Māori construct of mana is defined as a supernatural force that confers prestige, authority, control, power, influence, status, spiritual power, and charisma … Children are recognised as being born with intrinsic mana, which links them to the spiritual realm, to their ancestors, to living people and to places as well as to other entities in their environment … . (Ritchie and Phillips Citation2021, 12)

Making rain

Persephone crouches down and begins tapping her hands quickly, quietly, rhythmically on the fake grass that surfaces the gallery floor. The other artists crouch and join her. ‘Do you hear the sound of rain?’ The children seem to notice the sound of tapping first. Then they notice the hands of the artists tap-tap-tapping on the floor. Lastly, they notice the smiling faces of the crouching artists, and then the final straw, a gesture of ‘come on!’, the beckoning of Persephone’s hand calling them forward. Slowly, like furtive little creatures, the children creep into the circle and begin to tap their hands on the plastic grass. Several are still a little too shy, gripping onto the parent’s legs and clothing, straining to refuse the lure of the rhythmic circle. The adults seem to palpably want the children to participate. This is part of what they came for. After a minute or two the last stragglers join the rain-making circle. The tapping builds in intensity, growing to the roar of a thunderstorm, then it stops.

‘Now crunch yourself down into a tiny, tiny, tiny little seed. And now you’re going to soak up all the rain you just made’. It’s amazing how small children can make themselves. They become ovoids, asymmetrical round little seeds. Persephone unscrunches herself and begins dancing around the circle. ‘Here, do you want a little sun? A little rain? A bit of mud?’ She sprinkles each of the little seeds with invisible particles. The little seeds giggle and wobble in their contracted positions, as if they can actually feel themselves getting sprinkled with wetness. ‘Now feel yourself start to grow, with all that wonderful sun and rain, and grow and grow bigger and bigger!’ The seeds begin to unfurl and grow back into little children, stretching arms, jumping off the ground to grow even higher. It’s loud in the gallery now, not so much with discernible words, but with inchoate shrieks of laughter, joy, intensity, life. The whole atmosphere of the place has shifted into a different register.

Animist pedagogies

I am intrigued by how these initial rain-making exercises invoke connections between children’s bodies and the elemental processes that animate a seed’s germination. And while this activity may bear certain resemblance to ritualistic practices, it does not carry the ceremonial significance and efficacy of ritual as elaborated within many Indigenous wisdom traditions. Cajete describes how Indigenous peoples cultivated and refined complex ‘ritualistic expressions around the recognition, celebration, and evocation of mutualism with the natural environment’ (in Cajete and Williams Citation2020, 1721). Indigenous rituals often work to enhance and recalibrate animate relations between human and nonhuman agencies while also marking the beginnings and endings of worlds in highly situated and specific ways (Bawaka Country Citation2022).

Recently I collaborated with an ethno-choreographer and two ethno-musicologists to explore the impacts of climate change on animist rituals practiced by Indigenous peoples in Brazil, Trinidad, and Bali. Thinking through the concept of the pluriverse, we explore how each of these rituals incorporates complex sets of worldmaking practices which bring human and nonhuman animacies into purposeful and mutually transformative relation (Rousell et al. Citation2022). Describing her immersion in the choreographic practices of the Kuikuro peoples in the Central Amazon, ethno-choreographer Birgitte Bauer-Nilsen notes how ritual is essential for the spiritual and physical wellbeing of the multispecies community they have sustained for millenia.

I gradually learn that all the artefacts of the ritual have a soul with a spiritual affect and effect. The feather from a certain bird, the paint on the body, the necklace shells from the river, the jaguar skin and the teeth. There is deep respect and honour for all the artefacts of the ritual. I begin to sense a different kind of interconnectedness between the human and non-human, not just a connection of one thing with another, but a connection of mutual inclusion. Co-constitution. Worldmaking. (Rousell et al. Citation2022, 267)

We suggest that animist rituals can also be understood as pedagogies through which ‘memories, epistemology, ontology, sound and affect, multiple physical materials with earlier lives (in trees, in the earth) and lives yet to come … all become joined, metabolised, knotted together in entanglements of sinuous threads’ (Rousell et al. Citation2022, 277). And while animist rituals may have very specific ceremonial significance and ramifications within Indigenous communities, everyday ritual practices within western societies may also hold considerable pedagogical power in shaping relations of co-existence and interdependence. We might consider, for instance, the ‘rain making’ process described above as a type of animist pedagogy, and it is perhaps not surprising that young children are almost immediately engaged with the process of becoming seeds.

Early childhood researcher Jane Merewether (Citation2020) argues that young children often ascribe animist agency to the rocks, plants, clouds, puddles, animals, and technologies they encounter in everyday environments, and are also often moved to develop elaborate rituals around these encounters and relationships. Merewether critiques the work of childhood psychologist Jean Piaget who positioned children’s animistic tendencies as ‘primitive’ developmental stages which are subsequently ‘corrected’ by rational thought. The animist practices of Indigenous peoples were similarly characterised as ‘pre-rational’ by Western anthropologists in the 19th and 20th centuries (cf Descola Citation1996; Harvey Citation2006), arguably contributing to a pervasive ‘fear of animism’ that continues to haunt Western societies (Stengers Citation2018).Footnote2 This fear of animism is not simply a matter of different cultural ‘beliefs’ or logical preferences for particular accounts of the world, but a deeply political issue connected to questions of who (and what) matters under conditions of climatological crisis and catastrophic biodiversity loss.

Troubling the logocentric fear of animism in childhood development studies, Merewether (Citation2019a, Citation2020) argues for an ‘enchanted animism’ which values young children’s sensitivity to more-than-human relations of sentience, care, and sociality. If western science now tells us that forests think, converse, remember, pass down knowledge over time, and care for their young, then maybe young children’s animistic intuitions should be reconsidered and revalued. However, the assumption that children’s insights only become ‘truths’ once confirmed by western science remains troubling, and serves to reinforce a colonising hierarchy of knowledge which continues to relegate childhood to prerational stages of development. Rather than training children that animism is irrational (but trees really are sentient because science tells us so), perhaps we should be connecting children with animist pedagogies that value their intuitive sensibilities and welcomes them into an animate web of relations of which they are an integral part.

The mother

‘Ever played follow the leader?’ say Persephone. We’ve made our way outside now, and are gathering on the gravelly grounds of Birrarung Marr, just outside of the ArtPlay building. ‘Do you know how to march like this?’ Persephone starts marching off, knees kicking up high, arms swinging, following a curving trajectory around the ArtPlay building toward a series of large granite boulders and a small stand of She-Oak trees. Some of the children fall right into step behind her. Others climb up their parents’ body like a tree and into their arms, hitching a ride. ‘Now hop like a kangaroo!!’ They hop between the boulders and into the grove of She-Oaks. ‘Look up at these trees. These trees are upside down. Their roots are just as big as their branches up the top. What else do you think is down there, with the roots, underground?’.

‘Worms’, says one child quietly. ‘Cockroaches’, says another.

‘Treasure?’

‘Oh, I know. Chocolate coins!’

All the adults seem to find these answers quite amusing, and perhaps the children get the sense that they have done their job in amusing the adults.

Persephone says: ‘Do you know what else is down there? Mushrooms. And the mushrooms help the trees talk to each other. So this Mummy tree right here, she can talk to her baby trees over there through a mushroom that connects the roots together’. The children seem to take this mother-child analogy pretty seriously, at least the ones who are paying attention. A child crouches and gently strokes the roots of the ‘mother-tree’. She whispers softly: ‘the roots feel hard, like a rock, but smooth’.

Persephone gives the next prompt: ‘Now, make yourself into a mushroom. Put your mushroom ears on. Listen closely. What does the tree want?’

‘Carrots’, says one child. ‘Broccoli!’ says another. The adults chuckle again, like a punch line.

Persephone takes it a step further: ‘Can you hear those loud diggers over there? This tree is worried those diggers might come over. What would you do to tell the tree that it’s safe from the digger, that it’s okay?’

Children have started to scatter at this point, some lingering around the roots of the trees, brushing the bark with their hands. Others fuss, grapple, climb back into their parents’ arms. The artists sense a dispersal of energy, and begin orientating everyone back inside.

A child carried in her mother’s arms brushes her hand against the She-Oak tree named as ‘the mother’ when they pass by. I hear her whisper, ‘this mother is a big tree … is this tree higher than you Mummy?’ This comparison in scale is intriguing because it gestures beyond an obvious comparison of physical size. How big does Mummy loom in the child’s world compared to the tree? Alternatively, does the child’s presence even register in the world of the ‘mother-tree’ and the smaller ‘child-trees’ that surround it? Perhaps the question is not about who or what is larger, but how each comes to matter for others within an ecology of shifting attentions and dependency relations.

Anthropomorphism and multinaturalism

The passage above raises questions about anthropomorphism which continue to spark critical debate amongst Indigenous scholars and posthumanist researchers in early childhood (Merewether Citation2019b; Murris Citation2019; Nxumalo and Pacini-Ketchabaw Citation2017). Early childhood is so rife with attributions of anthropomorphic qualities to nonhuman beings in picture books, television shows, and films (Murris Citation2016), with some researchers arguing that this constitutes an overcoding of nonhuman life according to cultural hierarchies of human language, thought, and behaviour (Malone and Moore Citation2019). For instance, the naming of one tree as ‘mother’ and the others as ‘children’ could be read as the imposition of particularly cultured concepts of human gender and reproduction onto beings which do not (as far as we know) recognise gender categories. Further to this, the decided feminisation of the tree potentially reinforces historical associations of female and feminine bodies with both Romanticised and extractivist views of ‘nature’, where the feminine is considered somehow ‘closer’ to nature, and thus ‘naturally’ more sensitive, passive, malleable, and vulnerable to exploitation (Braidotti Citation2019).

One of the dangers of western anthropomorphism is that it can occlude the otherness of ontological difference between forms of life by making ‘others’ appear just like ‘us’. This can have the tendency to reproduce hierarchies and associations of sameness that have no actual correlate in ecological systems which rely on dynamic interactional differences between species to survive (West-Eberhard Citation2003). We learn from empirical studies of vegetal communities, for instance, that plants often carry multiple varieties of sexual organs that enable them to self-pollinate, self-seed, and even clone themselves (Wohlleben Citation2016). This helps us understand how the sexual reproduction of a plant (as in mycelium and fungal worlds) involves the self-generating proliferation of a single body across multiple generations and evolutions (Marder Citation2013; Tsing Citation2015). The question of what constitutes a single ‘body’ or an ‘individual’ (let alone a person, a mother, or a child) starts to get very slippery as we begin thinking with vegetal and mycelial worldmaking practices.

Notwithstanding these concerns, I am interested in what kinds of animist investments of desire the anthropomorphic naming of the tree as ‘mother’ may produce. As Arnold, Atchison, and McKnight (Citation2021, 142) note, ‘the attribution of human characteristics and qualities to plants has long been a way for Indigenous people’s representing their human interiority – a complex system for encountering the world’. Here we find that configurations of lived experience and identity are collectivised, not only in relation with other humans, but also with plants, animals, waterways, forests, and other nonhuman forms of life. Anthropomorphism in this key involves a recognition that whatever we recognise as ‘human’ experience is relationally generated through more-than-human practices of reciprocal worldmaking.

Drawing on decades of study with Amerindian societies in Brazil, Viveiros de Castro (Citation2005) describes how animals, spirits, tools, and elemental forces are often understood as persons who ‘see themselves as humans’ (38). He describes this as a ‘multi-naturalist’ perspective, in which nonhuman beings ‘perceive themselves to be or become anthropomorphic’ when they participate in co-habitation and kinship relations with other beings. And yet, this multi-naturalist attribution of the ‘human’ to other species still recognises, indeed celebrates, ontological pluralism and the self-differentiating singularity of each worldly perspective (Laird, Citation2021).

What animism claims, ultimately, is not so much that [other species] are similar to humans but rather that they – like we – are different from themselves: the difference is internal or intensive … If we all have souls, nobody is identical. If anything can be human, then nobody is unequivocally human. (Viveiros de Castro Citation2005, 52)

… you (mis)take the wind outside for your father’s wheezy breathing in the next room; you get up too fast and see stars; a plastic topographical map reminds you of the veins on the back of your hand; the rhythm of the cicadas reminds you of the wailing of an infant; the falling stone seems to express a conative desire to persevere … Maybe it is worth running the risks associated with anthropomorphising (superstition, the divination of nature, romanticisation) because it, oddly enough, works against anthropocentrism: a chord is struck between person and thing, and I am no longer above or outside a nonhuman ‘environment’. (Bennett Citation2010, 12)

The underground world

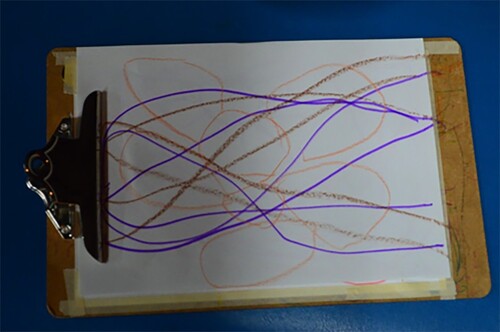

We are back in the gallery space, parents and children spread around the edges of the plastic grass floor. The artists hand out transparencies and coloured markers, and invite the children to draw how the She-Oak trees are talking to each other underground. I am sitting next to a young boy named Jasper, probably around 3 years old, who had previously spent most of the workshop in his mother’s arms. I notice Jasper detach somewhat from his mother to begin this task, his back still in contact with her legs. What surprises me in this interval is the certainty with which he now takes on the task of drawing the vegetal-mycelial underground network. This is an abstract task which asks you to draw something for which you have no visual reference. Yet Jasper confidently grabs an orange crayon and immediately draws a series of gently curving orange lines that double back on themselves. In no place are the lines jagged or broken, they are just one continuously smooth motion.

The lines end and Jasper puts the crayon down. He looks up at his mother and says ‘it’s finished’ with a sense of complete certainty. At this moment his mother is talking intently with one of the other mothers, they might have arrived together, and she doesn’t take much notice of Jasper’s drawing. He decides to continue. He grasps a brownish crayon this time, and draws a line that starts from the bottom right of the page, twists and changes directions in the upper middle section, and then completes itself on the bottom left. Seemingly satisfied with this articulation, he grabs a purple marker and creates a third line that closely resembles the last. The overall effect is one of layers of entanglement, a complex of lines that speak of secret connections, subterranean proliferations, and the infinite curve of a life lived in motion ().

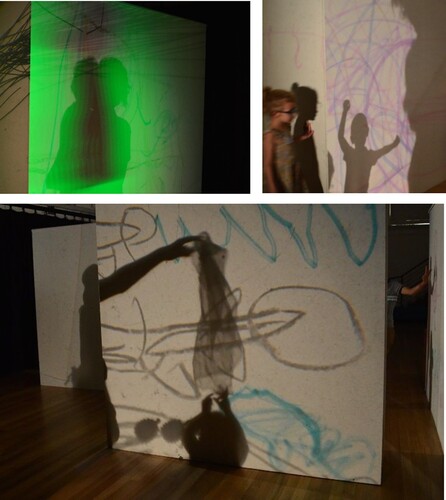

‘You’ve all drawn some amazing underground worlds here. Are you ready to go into the underground world now?’ Persephone asks. The children put down their drawing instruments and appear to be very interested in what will come next. The artists begin to collect the sheets of transparent drawings. I notice that green light has now flooded the performance space next door, along with the polyrhythmic sounds of bird calls. None of the children or parents have yet entered this space, but it’s just barely visible through a cracked doorway between the gallery and main performance space. Suddenly we see a young child advancing toward this green sliver of light, then passing through into the chromatically saturated performance space. It’s Jasper, who had previously been so hesitant to leave his mother’s arms. We see Jasper’s mother still sitting in the gallery, chatting with another parent. Persephone is still talking to the other children, preparing them to enter the space. But Jasper passes the threshold alone, pushing forward into the thick green atmosphere of the forest’s underground world.

Dependency relations

Drawing on their work in both Maori and Australian Aboriginal communities, Ritchie and Phillips (Citation2021) describe how children are trusted to explore their environments independently from a very young age. They contrast this with western tendencies toward risk aversion and protection of children from the slightest social or environmental threats. I was intrigued, therefore, to witness the process by which Jasper detached from his mother and began to explore the dark corners of the underground world. What set of conditions and elements might have enabled this to happen?

In his influential book Playing and Reality, child psychologist D. W. Winnicott (Citation1989) studies how different play environments enable children to put internal and external worlds into transformative relation, a phenomenon he called ‘transitional space’. Transitional space is not just about the physical spaces that a child might enter, but the intensive feeling of change taking place as distinctions between inside and outside become porous, malleable, and susceptible to transformation. Transitional space therefore describes a creative transitioning of experience that dissolves fixed boundaries between body, mind, culture, and environment.

More recently, media theorist Elizabeth Ellsworth (Citation2005) has reinterpreted Winnicott’s concept of transitional space to study the complex pedagogical affects generated by contemporary art, architecture, performance, and immersive media environments. She argues that creative environments may hold the possibilities for transitional space to emerge, but it is only through embodied and affective events that transitional space actually instantiates. Did the darkness of the underground world call Jasper into the space? Or was it the shimmering fluctuations of the multi-coloured lights?

Winnicott described such configurations of elements in terms of a ‘good-enough holding environment’, referencing the immersive sensation of being held as a child. For Winnicott, a holding environment is ‘good enough’ if it provides the conditions for a child’s incremental movement from dependence to independence. Yet, as many feminist and posthumanist theorists of childhood have argued (Giorza Citation2021; Murris Citation2016; Olsson Citation2009; Taylor, Pacinini-Ketchabaw, and Blaise Citation2012; Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2022), conventional accounts of child development often offer reductive and simplistic accounts of this movement from dependency to independence. As Taylor et al. write (Citation2012, 81), ‘the notion of the autonomous individual child perpetuated by child development theory is not only an illusion, it is also a grossly inadequate conceptual framework for responding to the challenges of growing up in an increasingly complex, mixed-up, boundary blurring, heterogeneous, interdependent and ethically confronting world’. How might we grasp Jasper’s movement into the underground world not as a step in the normative journey toward independence, but as an aleatory leap from one world of dependencies into another?

Dancing the pluriverse

The rest of the children follow Jasper through a vaulted entrance in the gallery space and into the underground world. Their first adventure in the underground world begins with an exploration of coloured light emitting from floor lamps, which produces multiple shadowing versions of their bodies as they move through the space. This initial experimentation then shifts into an exploration of the children’s own drawings, which begin to dance across the surfaces of over-head projectors in a whimsical fashion, along with found materials such as sheoak nuts, pine needles, and drops of water ().

As we move through these spaces I notice that the children are significantly less engaged with their parents and carers than in earlier stages of the workshop. I had firstly noticed this shift when Jasper left his mother to enter the underground environment alone, but now most of the children are interacting with the light, colour, and materials while their parents follow them around. Several children are beginning to experiment with the environment in ways that contradicted their dependency on the parent, and in some cases, their own fears and anxieties. For instance, one very young child (around two years old) had earlier told her mother that she was afraid to enter the underground world because she was scared of the dark. But now we see her crouching alone, away from the rest of the children, in a very dark corner of the space with a mixture of horror and exhilaration on her face.

Making kin otherwise

These ethnographic stories collected from Wood Wide Web show how young children can shift dynamically from a primary dependency on the parent into a different set of dependencies involving light, colour, darkness, seeds, leaves, mushrooms, bacteria, and soil. They witness a shift of dependency relations onto elemental forces of the Earth that agitate outside the bandwidth of human perception and consciousness: unknowable, dark, subterranean, pluriversal, opaque relations of dependency which are speculative, and yet nonetheless deeply affective. In order to grasp this shift, we need to acknowledge that dependency relations are not only physical and yoked to survivalist use-value. Dependencies are also highly affective, incorporeal, errant, and indeterminate forms of reciprocal relation. As Aboriginal philosophies teach us, ecological dependency relations constitute the very condition of physical embodiment and speculative thought, such that thinking and the capacity for metaphysical experience are inextricably woven into the very fabric of nature (Arnold, Atchison, and McKnight Citation2021; Bawaka Country Citation2022; Cajete and Williams Citation2020). There is, in this respect, a crucial connection between the kinds of ecological thinking and perception that acknowledge multispecies animacy and the sociopolitical transformation needed to effectively respond to climate change and catastrophic loss of biodiversity (Celermajer et al. Citation2021; Kirksey Citation2015).

In creating spaces for children to become aware of and responsive to interconnections and dependency relations across species, they also learn to embrace the tentacular darkness of Earthly forces that lurk underneath our all-too-human experiences of the world. This may involve a type of anthropomorphism, but in a speculative key which takes into account reciprocal relations of response-ability with the more-than-human. Barad (Citation2011) describes response-ability as a process of ‘opening up a space for response – that is, making an invitation to the other to respond by putting oneself at risk and doing the work it takes to truly enable a response, thereby removing (some of) the weight of the encrusted layers of nonhuman impossibilities (or at least drilling a hole through and allowing some air to circulate)’ (7).

As Bennett (Citation2010) suggests, every moment of our lives relies on a chord struck between human and nonhuman dependency relations as a vibrantly real event with resonant effects in the material world. To the extent that the insides and outside of our bodies are literally crawling with nonhuman life, the human body is already a pluriverse where many worlds converge without ever becoming intelligible to one another. Haraway (Citation2016) has figured this as a process of ‘symbiogenesis’, whereby ontologically heterogeneous forms of life enter into the co-construction of reciprocal worlds. Attuning to how these relations matter is both the challenge and promise of a pluriversal approach to childhood studies which listens carefully to the crossings between worlds, including worlds which are ending and others which may just be coming into existence ().

From dependencies to dependencies

As I’m preparing to leave ArtPlay I notice that someone has gathered all the children's transparent drawings up in a pile. They are sitting on a little table seemingly forgotten. Glancing down through the layers of children’s drawings, it seems clear that there is never a stage or moment of life that transcends the intricate dependencies which are the relational conditions for co-existence. Worlds are made of dependencies, all the way down to the quantum scale. Life is just a continuous movement from dependencies to dependencies, never achieving the humanist myth of independence and mastery.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the contributions of Andreia Caicedo and Kelly Chan to the data collection across multiple projects in the New Ideas Lab between 2020 and 2021.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Passing on traditional knowledge in Australian Aboriginal societies is a living practice of continuous variation rather than a transmission of static knowledge. The word ‘traditional’ refers to the act of living knowledge on and as Country, which includes ecological knowledge, medical knowledge, environmental management knowledge and cultural and spiritual knowledge, through intergenerational worldmaking systems (Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council Citation2020).

2 The origins of the term ‘animism’ have also come under significant critique in the field of anthropology, where it has been used since the 19th century to describe indigenous cosmologies that attribute personhood, interiority, and subjectivity to nonhuman beings (Bird-David Citation1999; Descola Citation1996; Harvey Citation2006). More recently, there have been discussions of emerging ‘new animisms’ as Indigenous ontologies find new terms of relevance in addressing contemporary problematics such as climate change (Bawaka Country Citation2022), the cryogenic preservation of extinct species (TallBear Citation2017), and the rise of artificial intelligence (Lewis et al. Citation2018).

References

- Arnold, C., J. Atchison, and A. McKnight. 2021. “Reciprocal Relationships with Trees: Rekindling Indigenous Wellbeing and Identity Through the Yuin Ontology of Oneness.” Australian Geographer 52 (2): 131–147. doi:10.1080/00049182.2021.1910111.

- Barad, K. 2011. “Nature’s Queer Performativity.” Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences 19 (2): 121–158. doi:10.5250/quiparle.19.2.0121.

- Bawaka Country, including Wright, S., S. Suchet-Pearson, K. Lloyd, L. Burarrwanga, R. Ganambarr, M. Ganambarr-Stubbs, B. Ganambarr, and D. Maymuru. 2015. “Working with and Learning from Country: Decentring Human Authority.” Cultural Geographies 22 (2): 269–283. doi:10.1177/1474474014539248.

- Bawaka Country, including S. Wright, S. Suchet-Pearson, K. Lloyd, L. Burarrwanga, R. Ganambarr, and J. Sweeney. 2016. Co-Becoming Bawaka: Towards a Relational Understanding of Place/Space. Progress in Human Geography, 40 (4): 455–475.

- Bawaka Country, including Wright, S., S. Suchet-Pearson, K. Lloyd, L. Burarrwanga, R. Ganambarr, M. Ganambarr-Stubbs, B. Ganambarr, and D. Maymuru. 2020. “Gathering of the Clouds: Attending to Indigenous Understandings of Time and Climate Through Songspirals.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 108: 295–304. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.05.017.

- Beiler, K. J., D. M. Durall, S. W. Simard, S. A. Maxwell, and A. M. Kretzer. 2010. “Architecture of the Wood-Wide Web: Rhizopogon spp. Genets Link Multiple Douglas-Fir Cohorts.” New Phytologist 185 (2): 543–553. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03069.x.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press.

- Bird-David, N. 1999. “‘Animism’ Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology.” Current Anthropology 40: S67–S91. doi:10.1086/200061.

- Blaser, M., and M. de la Cadena. 2018. “Pluriverse: Proposals for a World of Many Worlds.” In A World of Many Worlds, edited by M. de la Cadena and M. Blaser, 1–22. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Braidotti, R. 2019. Posthuman Knowledges. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Briggs, C. 2008. The Journey Cycles of the Boonwurrung: Stories with Boonwurrung Language. Melbourne: Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages.

- Bawaka Country, including Burarrwanga, L., R. Ganambarr, M. Ganambarr-Stubbs, B. Ganambarr, D. Maymuru, K. Lloyd, S. Wright, S. Suchet-Pearson, and L. Daley. 2022. “Songspirals Bring Country into Existence: Singing More-Than-Human and Relational Creativity.” Qualitative Inquiry 28 (5): 435–447.

- Cajete, G. 2006. “It is Time for Indian People to Define Indigenous Education on Our Own Terms.” Tribal College 18 (2): 56.

- Cajete, G. A., and D. R. Williams. 2020. “Eco-aesthetics, Metaphor, Story, and Symbolism: An Indigenous Perspective: A Conversation.” Research Handbook on Childhoodnature: Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research, 2: 1707–1733. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-67286-1_96.

- Castillo, M. R. F. 2016. “Dancing the Pluriverse: Indigenous Performance as Ontological Praxis.” Dance Research Journal 48 (1): 55–73. doi:10.1017/S0149767715000480.

- Celermajer, D., D. Schlosberg, L. Rickards, M. Stewart-Harawira, M. Thaler, P. Tschakert, B. Verlie, and C. Winter. 2021. “Multispecies Justice: Theories, Challenges, and a Research Agenda for Environmental Politics.” Environmental Politics 30 (1–2): 119–140. doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1827608.

- Cole, D. R., and M. Somerville. 2017. “Thinking School Curriculum Through Country with Deleuze and Whitehead: A Process-Based Synthesis.” In Art, Artists and Pedagogy, edited by C. Naughton, G. Biesta, and D. Cole, 71–82. NY: Routledge.

- De Castro, E. V. 2005. “Perspectivism and Multinaturalism in Indigenous America.” In The Land Within: Indigenous Territory and Perception of the Environment, edited by A. Surralles and P. G. Hierro, 36–75. Copenhagen: IWGIA.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus (B. Massumi, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Demos, T. J. 2020. Beyond the World’s End: Arts of Living at the Crossing. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Descola, P. 1996. In the Society of Nature: A Native Ecology of Amazonia. Translated by Nora Scott. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ellsworth, E. 2005. Places of Learning: Media, Architecture, Pedagogy. NY: Routledge.

- Escobar, A. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Gay-Wu Group of Women, including Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr-Stubbs, M., Ganambarr, B., Maymuru, D., Wright, S., … & Lloyd, K. 2019. Songspirals: Sharing Women's Wisdom of Country Through Songlines. Allen & Unwin.

- Giorza, T. M. 2021. Learning with Damaged Colonial Places: Posthumanist Pedagogies from a Joburg Preschool. Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Harris, A. M., and S. H. Jones. 2019. The Queer Life of Things: Performance, Affect, and the More-Than- Human. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Harvey, G. 2006. Animism: Respecting the Living World. Columbia University Press.

- Hernández, K., J. M. Rubis, N. Theriault, Z. Todd, A. Mitchell, B. Country, L. Burarrwanga, et al. 2021. “The Creatures Collective: Manifestings.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 4 (3): 838–863.

- Hooper, R. 2021. “The Wisdom of the Woods.” New Scientist 250 (3332): 39–43. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(21)00747-8.

- Kirksey, E. 2015. Emergent Ecologies. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Kohn, E. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Kolasa, A. 2017. “Yiookgen Dhan Liwik-al Intak-kongi Nganyinu Ngargunin Twarn / Dreams of our Ancestors Hopes for our Future.” (Parliamentary Speech), 22 June 2017, Wurundjeri. Accessed January 18, 2022. wurundjeri.com.au/wpcontent/uploads/pdf/Wurundjeri_parliamentary_speech_download_a.pdf.

- Kopenawa, D., and B. Albert. 2013. The Falling Sky. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Laird, T. 2021. Wrapped in Flowers, Listening to Frogs. Art + Australia [Special Issue: Multinaturalism] 57 (18): 10–19.

- Law, J. 2015. “What’s Wrong with a One-World World?” Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory 16 (1): 126–139. doi:10.1080/1600910X.2015.1020066.

- Lewis, J. E., N. Arista, A. Pechawis, and S. Kite. 2018. “Making Kin with the Machines.” Journal of Design and Science.

- Macfarlane, R. 2016. “The Secrets of the Wood Wide Web.” The New Yorker 7.

- Malone, K., and S. J. Moore. 2019. “Sensing Ecologically through Kin and Stones.” International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 7 (1): 8–25.

- Marder, Michael. 2013. Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life. New York: Colombia University.

- Merewether, J. 2019a. “Listening with Young Children: Enchanted Animism of Trees, Rocks, Clouds (and Other Things).” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 27 (2): 233–250. doi:10.1080/14681366.2018.1460617.

- Merewether, J. 2019b. “New Materialisms and Children’s Outdoor Environments: Murmurative Diffractions.” Children’s Geographies 17 (1): 105–117. doi:10.1080/14733285.2018.1471449.

- Merewether, J. 2020. “Enchanted Animism: A Matter of Care.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 1463949120971380. doi:10.1177/1463949120971380.

- Murris, K. 2016. The Posthuman Child: Educational Transformation Through Philosophy with Picturebooks. Oxon: Routledge.

- Murris, K. 2019. “Posthuman De/Colonising Teacher Education in South Africa: Animals, Anthropomorphism and Picture-Book Art.” In Why Science and Art Creativities Matter, edited by P. Burnard and L. Colucci-Grey, 52–78. Leiden, NL: Brill.

- Nxumalo, F., and V. Pacini-Ketchabaw. 2017. “Staying with the Trouble’ in Child-Insect-Educator Common Worlds.” Environmental Education Research 23 (10): 1414–1426. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1325447.

- Olsson, L. M. 2009. Movement and Experimentation in Young Children’s Learning: Deleuze and Guattari in Early Childhood Education. Oxon: Routledge.

- Povinelli, E. A. 2016. Geontologies: A Requiem for Late Liberalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Powers, R. 2018. The Overstory: A Novel. NY: WW Norton & Company.

- Ritchie, J., and L. G. Phillips. 2021. “Learning with Indigenous Wisdom in a Time of Multiple Crises: Embodied and Emplaced Early Childhood Pedagogies.” Educational Review 75 (1): 54–73. doi:10.1080/00131911.2021.1978396.

- Rose, D. B. 2011. Wild Dog Dreaming: Love and Extinction. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Rosiek, J. L., J. Snyder, and S. L. Pratt. 2020. “The New Materialisms and Indigenous Theories of non-Human Agency: Making the Case for Respectful Anti-Colonial Engagement.” Qualitative Inquiry 26 (3–4): 331–346. doi:10.1177/1077800419830135.

- Rousell, D. 2022. “Accidental Creatures: Whitehead’s Creativity and the Clashing Intensities of More-Than-Human Life.” Qualitative Inquiry 28 (5): 566–577. doi:10.1177/10778004211065811.

- Rousell, D., and A. Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles. 2022. Posthuman Research Playspaces: Climate Child Imaginaries. New York: Routledge.

- Rousell, D., E. Ryan, B. Bauer-Nilsen, and R. Lai. 2022. “Animist Pedagogies and the Endings of Worlds: Rituals for the Pluriverse.” In Doing Rebellious Research in and Beyond the Academy, edited by P. Burnard, L. MacKinlay, D. Rousell, and T. Dragovic, 263–272. Leiden, NL: Brill.

- Saunders, M. 2021. “The Land is the Law: On Climate Fictions and Relational Thinking.” Art + Australia: Multi-Naturalism 8: 21–31.

- Stengers, I. 2018. “The Challenge of Ontological Politics.” In A World of Many Worlds, edited by M. de la Cadena and M. Blaser, 83–111. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- TallBear, K. 2017. “Beyond the Life/Not Life Binary: A Feminist-Indigenous Reading of Cryopreservation, Interspecies Thinking and the New Materialisms.” In Cryopolitics: Frozen Life in a Melting World, edited by J. Radin and E. Kowal, 179–202. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Taylor, A., V. Pacinini-Ketchabaw, and M. Blaise. 2012. “Children’s Relations to the More-Than-Human World.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 13 (2): 81–85. doi:10.2304/ciec.2012.13.2.81.

- Tsing, A. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World on the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council. 2020. “‘Taking Care of Culture’ Discussion Paper. State of Victoria’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Report, November 2020. https://www.aboriginalheritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/taking-care-culture-discussion-paper.

- Viveiros de Castro, E. 2005. “Perspectivism and Multinaturalism in Indigenous America.” In The Land Within: Indigenous Territory and Perception of the Environment, edited by A. Surralles and P. G. Hierro, 36–75. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- West-Eberhard, M. J. 2003. Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Whitehead, A. N. 1978. Process and Reality. New York: Free Press.

- Whyte, K. P. 2013. “On the Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as a Collaborative Concept: A Philosophical Study.” Ecological Processes 2 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1186/2192-1709-2-7.

- Wild, A., A. Reed, B. Barr, and G. Crocetti. 2020. The Forest in the Tree: How Fungi Shape the Earth. Melbourne: CSIRO.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1989). Playing and Reality. New York: Routledge.

- Wohlleben, P. 2016. The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries from a Secret World. Greystone Books.