ABSTRACT

This study analyzed sixth-graders' perceptions of a year-long education program promoting activism for climate change in Israel. The program aimed to encourage students to lead activities mitigating and adapting to climate change. The research questions were: 1) What are sixth-graders' attitudes towards climate change education? and 2) What program components foster proenvironmental behavior and willingness to reduce the impact on climate change? Qualitative analysis used written summaries, drawings, and focus group feedback at four intervals. The results showed that while students' climate change concerns remained, they developed a sense of self-efficacy for leading activism. They recommended continuing the program, expanding it to lower grades, and providing opportunities to experience activism. The study suggests promoting behavioral change regarding climate change in sixth grade may be effective as children develop their environmental attitudes and perspectives. The research highlights the importance of climate change education, which can encourage activism to mitigate and adapt to climate change among young children.

Introduction

Climate change is a transboundary global emergency (IPCC Citation2022; Vergunst and Berry Citation2022) that affects different populations differently. For example, children, compared to adults, are more sensitive to the negative effects of the climate change phenomenon (O’Malley Citation2015). Therefore, it is important that as many populations as possible not only learn about the phenomenon of climate change (Rushton and Walshe Citation2022) but also work to reduce its effects (Littrell et al. Citation2020). Despite this, there is a research bias in that only a few studies have focused on demographics under 14 years of age (McDonald-Harker, Bassi, and Haney Citation2022). This bias is counterproductive to the literary demand for encouraging a wide range of people of different ages to deal with the issue of climate change, and encouraging action designed to reduce the effects of the phenomenon (Littrell et al. Citation2020; McDonald-Harker, Bassi, and Haney Citation2022).

Apparently, there are a variety of reasons that result in this research bias. Some argue that climate change is too complex an issue for the young (Lawson et al. Citation2018), or that climate change evokes negative emotions (Manni, Sporre, and Ottander Citation2017; Ojala Citation2012, Citation2015). Others excuse the bias because they argue that young children feel helpless in the face of the phenomenon (Tayne et al. Citation2021), while some claim that children lack the ability to look at the picture in a comprehensive way (Gal Citation2022). Still others claim that specific skills are needed to reduce and adapt to climate change (Tayne et al. Citation2021), while some claim that teachers do not understand the subject enough to be able to teach it (Jones and Davison Citation2021).

One of the ways to cope with the impact of climate change and develop community resilience is through formal education in schools (McDonald-Harker, Bassi, and Haney Citation2022; Trott Citation2021). However, developing a curriculum on climate change education (CCE) in a school is complex because the subject includes the need for political, social, economic, environmental and emotional consideration (Gal Citation2022; Littrell et al. Citation2020). Addressing these issues can be a minefield. Besides the reluctance of schools to integrate political aspects into teaching, sometimes, CCE can contradict the attitudes of the students’ parents (Bleazby et al. Citation2022).

While there is encouragement for the implementation of CCE, there is also criticism about the structure of CCE curriculum. Some claim that it is too focused on scientific knowledge and that social processes almost never occur in these programs (Dunlop and Rushton Citation2022; Foss Citation2018). Social processes are important because it is known that children's experiences and attitudes develop through socialization. They are shaped by the social influences of their peers, parents, teachers and other adults (McDonald-Harker, Bassi, and Haney Citation2022; O’Malley Citation2015). In addition, more often than not, the CCE curriculum only attributes children a passive role in the context of their families and communities (O’Malley Citation2015). Another criticism is related to the poor way of integrating CCE into the school curriculum. In quite a few cases, CCE constitutes a complementary subject to an existing discipline (Dunlop and Rushton Citation2022). Further critiques of CCE refer to too much focus on the transfer of scientific knowledge, which is not considered to be a solution to children's concerns about climate change (Foss Citation2018). These critics add that the existing CCE curricula do not provide sufficient grounds for activism as part of children’s experiences in reducing the impact of the climate change phenomenon (Dunlop and Rushton Citation2022) and do not provide empowering opportunities that encourage environmental leadership in the young (Trott Citation2021). The initiators of environmental programs are also criticized. In most cases, this is because planning and implementation is top-down and only creates cosmetic change, not meaningful change (Dunlop and Rushton Citation2022). In light of the literary criticism of existing CCE programs, and the understanding that there is no dispute about the importance of studying CCE in schools, the question, then, is how to teach CCE (Orhan Citation2022).

Responding to the need to help children understand and develop effective responses to climate change, teachers at an elementary school in Northern Israel designed a CCE program, which also endeavored to respond to some of the literary criticism about CCE. The CCE program is an initiative of the school itself and was pre-dated the Ministry of Education’s mandatory CCE curriculum. The program was implemented as a separate subject with children aged 11–12 (sixth-graders) and ran over a full school year. It focused on environmental activism, not only the acquisition of knowledge, and involved intergenerational learning experiences. In light of the existing discussion in the literature regarding the need to teach CCE at a young age in a formal school setting, the aim of this study was to examine the perceptions of the sixth-graders in relation to the CCE program and environmental activism experiences.

Literature review

Two central concepts are at the core of the CCE curriculum designed and implemented at the school in Northern Israel (see Appendix 1): environmental activism and self-efficacy to promote environmental activism. These core concepts are discussed below.

Environmental activism

At the beginning of the millennium some defined environmental activism as the actions of the public to effect environmental change (Lubell Citation2002). About 15 years later there were those who used the term ‘daily environmental activism’. This definition included efforts made by people in a personal or collective way to adjust their day-to-day activities in response to the concern that their behavior caused damage to the environment (Walker Citation2017).

Daily activism is valued for its symbolic meaning, through activities that represent a lifestyle focused on changing patterns of sustainability, or a young population. Everyday activism is usually confined to personal circles of influence (Trott Citation2021). It symbolizes cultural change, social change and mental change (O’Brien, Selboe, and Hayward Citation2018). Even if the impact is limited it may represent what the world needs more of, that is, behavioral change (Taylor Citation2019). In addition, it is possible that daily activism could help reduce the sense of hopelessness in the younger generation. It can be a bridge between the feelings about the phenomenon of climate change at the global level, which is often perceived as an abstract event, and a focus on concrete behaviors that are carried out in everyday life and which emphasize their importance (Ojala Citation2012). The daily activism carried out by the younger generation is of additional importance as their environmental activities are able to challenge the dominant view that children cannot be agents of social change (Trott Citation2021).

Self-efficacy to promote environmental activism

Self-efficacy is a general concept designed to explain how the individual relates to his/her ability to perform a behavior that will lead to a certain result. In the case of this study, it is the self-efficacy to reduce the impact on climate change. According to the literature, there are a wide variety of elements that influence self-efficacy to act for the environment (Hornsey, Chapman, and Oelrichs Citation2022). Bandura has defined four elements that produce high levels of self-efficacy: direct experience, indirect experience or learning through personal example (role model), verbal persuasion and emotional state (Bandura Citation1982, Citation2006). Contrary to Bandura, the literature also refers to a collective self-efficacy and not just to individual self-efficacy (Chawla Citation2020; Chawla and Cushing Citation2007). Other studies have focused on factors that predict environmental behavior (Walsh and Cordero Citation2019), by arguing, for example, that knowledge and attitudes (Kollmuss and Agyeman Citation2002), demographic parameters (McDonald-Harker, Bassi, and Haney Citation2022), connection to nature (Hungerford and Volk Citation1990), connection to parents (Trott Citation2022), level of involvement (Hornsey, Chapman, and Oelrichs Citation2022), physiological states (Ma, Cavanagh, and Mcmaugh Citation2022), analytical thinking (Hornsey, Chapman, and Oelrichs Citation2022), the level of self-belief of the individual (Walsh and Cordero Citation2019), and even social media (Trott Citation2022) influence the self-efficacy to act for the environment.

Research context

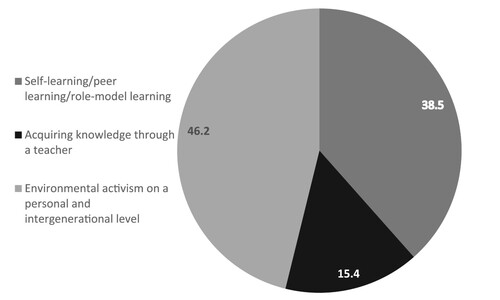

At the beginning of the 2021/2022 school year, a CCE program which included personal and public experiences in climate change activism was introduced into two sixth-grade classes at an elementary school in Northern Israel (see Appendix 1). In accordance with the recommendations in the literature, a significant component of the program was a focus on activism ().

The program was an initiative of the school staff and pre-dated the Ministry of Education’s mandatory CCE curriculum which began in 2021. Two teachers co-presented the program, one a qualified science teacher and the other a professional teacher with academic training in the fields of ecology, zoology, and the environment. For two hours a week, for the entire school year, the students learned about climate change issues and engaged in practical climate change activism. They learned about the structure of the atmosphere, greenhouse gases, the greenhouse effect, environmental pollutants, veganism, vegetarianism, environmental activism, environmental activists, the work of Greta Thunberg, the global ecological footprint and more. As part of the program, the students took a field trip to a power station where electricity production is mainly based on coal. In addition, during the year the students met with a tenth-grade student who is active in youth climate change activism in Israel.

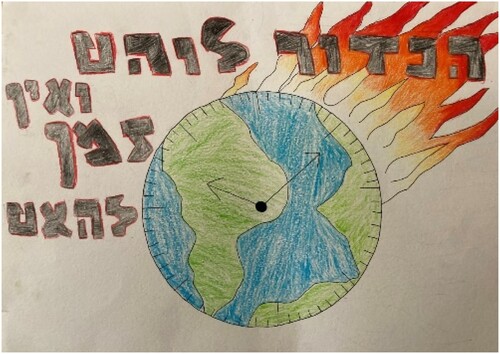

The educational processes

Along with the curriculum outlined above, the students experienced several educational processes related to CCE and activism during the school year. The first was the promotion of a democratic election campaign to select a CCE program logo. The students worked in small groups to design a climate change crisis logo. The logos were assigned a number and displayed in a week-long exhibition at the school with their designers’ identification concealed. Students of all ages viewed the exhibition and towards the end of the week, elections were held. On Election Day, sixth-graders visited each class, explained the process, and led the students to the voting room. Each student was given a ballot paper and stationery. After filling in their personal choice, the students put their ballot paper into a ballot box. At the end of the day, the teaching staff counted the votes and announced the winner ().

Figure 2. The winning logo in the democratic elections held at the school. Logo slogan: The earth is hot and there is no time to slow down.

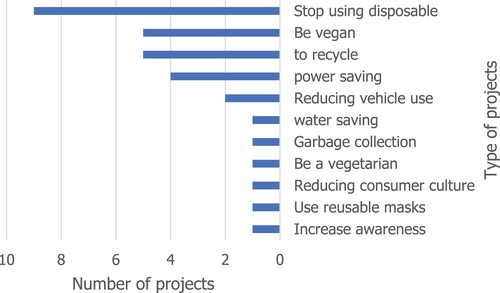

The second educational process involved promoting environmental activism at the personal level of individual students. Each student chose an environmental project related to personal behavioral change that was believed to help reduce his or her environmental impact and help reduce climate change. The activism project ran for two weeks ().

Figure 3. Distribution of personal activist projects designed to lead to behavioral change at the individual level.

74% of students (31 out of 42) carried out a personal activism project. The remaining 26% did not express any interest in participating and received approval from the school administration not to take part in it.

The third educational process involved promoting behavioral change at the community level. Working in small groups, the students chose a project that would allow for behavioral change among the population close to them to help reduce climate change. This population was defined as their classmates, teachers, and school community. The project lasted about two weeks; however, the planning and preparation took a long time. Students chose the following: an explanatory presentation to students at school about the ways to reduce human impact on the environment; activating relatives as part of a recycling program;, building a mobile library from a wooden cart (); building a mobile play trolley to collect and exchange games; distributing reusable masks as a means of preventing the spread of Corona virus instead of using disposable masks; replacing the use of disposable utensils in the school with reusable utensils; planting a forest around the school; organizing a demonstration on International Climate Change Day; collecting food scraps for animals; and building a green wall ().

Only two community projects were completed: raising awareness in classrooms and building a mobile library. At the time of writing, two projects were nearing completion: the building of a green wall, and a mobile play trolley to collect and exchange games. Due to time constraints the rest of the projects were discontinued at an advanced planning stage.

Research population and ethics

The study population included 42 students from two sixth-grade classes. All parents of the students received a written request seeking permission for their children's participation in the study. Consent was provided in writing. Informed consent was also obtained from the 42 students. Before administering each research tool, the purpose of the research was explained, orally, to the students. It was emphasized that the research tools would not form any part of the students’ assessment and non-participation in the research would not detract from their grades. It was also explained that there was no obligation to participate in the research and that students could abstain from the process. The study received the approval of the ethics committee of the academic institution where the researcher works.

Methodology

The aim of the study was to investigate two research questions: 1) What is the attitude of sixth-graders towards Climate Change Education (CCE)? and 2) What are the components of the CCE program that were significant in promoting their pro-environmental behavior and their willingness to reduce their impact on climate change? The research was based on a qualitative approach and used a case study method, based on a constructivist approach that seeks to describe a complex reality within a specific context (Zainal Citation2007). In most cases, a case study is used to examine a small geographical area or a limited number of people as the subjects of the study. In essence, case study is a way to focus on real-life phenomena through a detailed analysis of a few events or circumstances (Yin Citation2006). Yin defines the case study research method as an empirical study that investigates a contemporary phenomenon; as a study in which the boundaries between the phenomenon and the context are not clear; and as a study in which several sources are used as evidence (Yin Citation2006; Zainal Citation2007).

Research tools

This study used three qualitative research tools which are outlined below. The variety of research tools used in this study enabled the use of triangulation (Mostafavi Citation2021).

Drawings

The students made drawings illustrating their feelings toward CCE and climate change activism and wrote explanations for their drawings (Eldén Citation2013; Flowers et al. Citation2015). They made these at the beginning and end of the program and at the beginning and end of each activism experience (personal and community). Before the start of each activism experience, one week into it, and at the end, the students wrote a personal summary designed to allow them to express themselves freely in the context of the process. Seventy-nine drawings and the children’s explanations of their drawings were collected.

Letter to the minister

At the end of the year, as a written reflection summarizing the entire educational process, the students were asked to write a letter to the Minister of Education in Israel and describe their experiences in the new program. Students were asked to describe the individual and group environmental activism in which they took part, the challenges, successes, failures and to write recommendations for the coming years. There was a total of 247 written text sources from the students,

Focus groups

In addition to the above research methods, six focus groups (about half an hour each) took place in the school, where between six and seven students participated.

Data analysis

Text analysis included two steps (Saldaña Citation2014). In the initial coding phase, Descriptive Coding was used as part of the Elemental Coding Method. Descriptive Coding summarizes in a word or short phrase the written content that is the essence of the message. In this way basic labels are given to the data to provide the full range of topics that appear in the existing information. Descriptive Coding is suitable for studies involving a wide variety of different forms of data as reflected in this study. The purpose of second cycle coding is to organize the data generated in the initial coding cycle in a categorical, thematic, conceptual and/or theoretical way. In the case of this study, second cycle coding of the Pattern Coding type was used. This coding allows the amalgamation of similar data encoded in the primary cycle and the creation of evolving categories for key topics, the creation of rules, the examination of causes and explanations and patterns of human relations. (Linneberg and Korsgaard Citation2019; Onwuegbuzie, Frels, and Hwang Citation2016; Saldaña Citation2014).

The analysis of the drawings was achieved according to the Affective Method (Saldaña Citation2014) which allows a qualitative subjective investigation of human experience by direct naming of the experience. In the case of this study, Emotion Coding was used. The use of Emotion Coding is mainly suitable for research that deals with the practical experiences of participants, especially regarding social relationships, decision making and judgment of processes (Beazley, Butt, and Ball Citation2018; Hemming Citation2007; Kustatscher Citation2017). Considering emotions are universal, our knowledge of them allows for an in-depth differentiation of participants’ perceptions. Although there are many expressions to describe emotions, in the end the different codes can be divided into those that express positive emotions, negative emotions or those without emotions at all (Onwuegbuzie, Frels, and Hwang Citation2016; Saldaña Citation2014).

Findings

The findings are presented below in four sections and are structured according to the educational process that the students went through.

Process A: Students’ feelings before the CCE and activism program started. The findings in this section include text analysis of student summaries and analysis of their drawings.

Process B: Students’ feelings after one week of activism on a personal level and after two weeks of this experience. These feelings are presented through text analysis of the student summaries.

Process C: Students’ feelings before the second activism activity, at a community level. The findings in this section include text analysis of the student summaries.

Process D: Students’ feelings at the end of the school year and after experiencing two environmental activism projects and the visit to the power station. The findings in this section include text analysis of the student summaries, a personal letter sent to the Minister of Education, drawings analysis and focus group analysis.

Process A: students’ feelings before the CCE and activism program started – personal pro-environmental behaviour

From the analysis of the students’ words, two main categories emerged.

A.1 Anticipation. All students felt a sense of anticipation before their engagement in personal activism. Some felt encouraging or positive anticipation (A.1.1) while some felt inhibiting or negative anticipation (A.1.2).

A.1.1 Encouraging anticipation towards personal activism. The anticipation that encouraged action was expressed by a number of students. The first and most common was an expression of excitement: ‘I am excited about the project because I really want to succeed’. Further to the excitement, the student describes his longing for success in the project. Beyond the personal desire to succeed, students expressed positive anticipation through their desire to help the planet: ‘I am happy and excited because I know I may help the world, nature, life and man.’

A.1.2 Inhibiting anticipation towards personal activism. Expressions describing negative anticipation can be found mainly through the expression of pressure that appeared in a significant number of students’ responses: ‘I am a little stressed because I still do not know how to make time for it … I have a lot of classes and events’. In this case, the student’s stress stems from the need to spend time on personal activism over other assignments. In fact, students emphasize that the need to meet activism goals will require them to recalculate their free time distribution and are not sure they will find the time for activism.

Another example of inhibitory anticipation can be found in the use of the word ‘apprehensive’ as expressed in the words of one of the students: ‘I am also a bit apprehensive that I will not remember to recycle’. Another student wrote: ‘I am stressed because I do not know if I will persevere in the task’. In both cases, the concern the students have is in dealing with the need to implement a new behavior to which they are not accustomed. Another concern is related to the activism process itself. There is a fear among some students that the process will be difficult: ‘I am afraid it will be too difficult for me’. This student notes her low sense of ability to succeed in activism, even before the project begins.

A.2 The Activism Results. Most of the students claimed that they would be able to carry out the activism project: ‘I'm going to be able to not use the disposable masks for two weeks’. The student's words indicate high self-confidence and the determination to succeed. Some of the students claimed that they would only succeed if they really decided they wanted to: ‘If I want, I will succeed, I just have to decide’. For other students, the contrast between success and the need to remember the commitment to activism stood out, for example: ‘I think the process will work, it's pretty simple and easy … I just have to persevere’. Although it was a personal activist project, some students stated that they believed they would succeed in persuading others to change their environmental behavior, as one of the students noted: ‘I feel I will make a huge change in my community … people will enlist my help and make our community cleaner’. In contrast, there were those who were confident in their personal success but were unsure of the success of expanding circles of influence as one student wrote: ‘I feel I will succeed but I am not sure I will succeed in convincing my parents and siblings’.

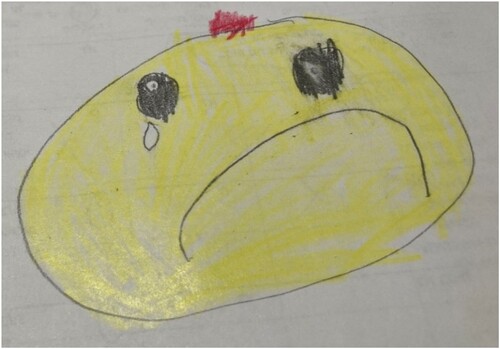

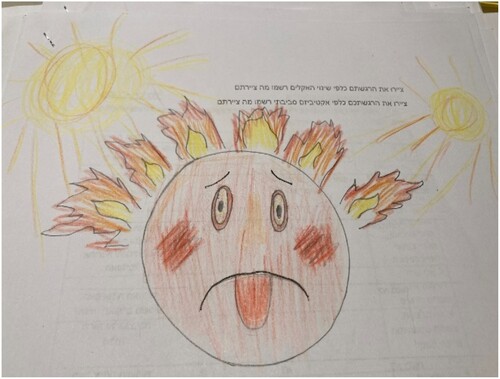

Before the students’ experience of environmental activism, they were asked to make a drawing to illustrate their sense of climate change and explain their drawings. In 84% of the drawings, a negative feeling was expressed toward climate change ( and ). The drawings were also accompanied by an explanation describing negative feelings about climate change.

Figure 7. A face that represents the earth and the feeling of heat emitted from it as a result of the sun heating it.

Only one drawing expressed neutral feelings about climate change: ‘I do not know how I feel’. Three drawings showed students’ positive emotions toward climate change. For example, ‘I drew the recent revival among people in Israel about climate change, we need to act’. This student is aware of the existing activity related to climate change in Israel and the desire to reduce the human impact on climate change. It also notes the fact that the time has come for action to be taken to reduce the effects of climate change.

Process B: students’ emotions after one week of activism on a personal level and after two weeks

B.1 Sense of Success. All students summarized the two weeks of their personal activism in words that describe a sense of success. The sense of success among students is divided between the sense of personal success and making a personal behavioral change, and the sense of success in influencing the community. While some of the students failed to meet 100% of the goals they set for themselves, this did not impair their sense of success. For example: ‘I did not eat dairy products except on Saturday, but despite this I consider my week as a good success’. The feeling of success in the family context is reflected in a behavioral change in the immediate family, as noted by a student at the end first week of activism: ‘ … We used disposable straws and then I suggested an idea to buy reusable straws and from today the whole family uses reusable straws — it gives me a sense of success’.

B.2 Challenges. The students described two main challenges. The first, was on a personal level. Students cited forgetfulness as one of the major challenges in making behavioral change. For example, ‘Sometimes I forgot and then I remembered. I was angry with myself’ (end of first week). The need to cope with giving up previous favorite foods was also noted by the students as a challenge: ‘I was a vegetarian, and it was hard because meat is the thing I really like’. Sometimes, the students could not resist their favorite food: ‘The problem I had was that my sister had a birthday and there were cakes that are made with milk, and I love cakes … I couldn't anymore so I just ate the cakes’. Despite the difficulty experienced by some students, they described this difficulty in positive words: ‘ … to me it's fun even though it's a little hard sometimes’ (end of first week). Another student expressed the self-conflict with her love of shopping. Her chosen activism was to reduce online purchases. However, during the experiment, Black Friday took place around the world. To distract herself from a weekend of shopping she attests: ‘I held back, I did other things I love to do’ (end of second week).

The second challenge was related to a lack of community cooperation. More than once, students noted the lack of cooperation from parents, siblings or relatives, which caused a challenge in dealing with personal activism. As one of the students noted at the end of the two weeks: ‘I did not like that my mother did not cooperate with me and wanted me to eat meat’. The student describes the conflict between herself and her mother over the need to eat meat, which is contrary to the goals the student had set for herself.

B.3 Personal Reflection. Following their activism, students were asked to write what they had learned about themselves. Most students were impressed that they were able to meet the challenges or goals they set for themselves. In addition, students attest to their ability to persevere. For example: ‘What I learned about myself is that I have tremendous perseverance … and if I want to change something no one can stop me’ (end of first week). In her summary at the end of the first week another student quoted a well-known Hebrew proverb: ‘There is nothing that stands in the way of desire’. She cited this proverb as part of her sense of success in meeting her activism goals.

B.4 Contribution to Environmental Preservation.

A further outcome of the students’ involvement in environmental activism was the positive feeling they had as a result of helping to reduce climate change, as one student noted: ‘I think the ability to do good is that we try to do good for the country and the world as part of climate change’. Sometimes, the link between activism and reducing the environmental impact was accompanied by words of satisfaction, as one student noted in the first summary: ‘I like that I preserve the environment and at least try to reduce the heat’. This student not only reports the satisfaction she feels in helping to preserve the environment, she also indicates in what way she did so.

Process C: students’ feelings before activism at the community level

Analyzing the students’ feelings before the activism at the community level raises two main categories.

C.1 Positive Feelings. Students describe a sense of excitement toward their second activism as expressed in these students’ words: ‘I am excited to do a big project and maybe change something’. The positive expectation in the students’ words is accompanied by a strong desire to start and act. The feelings of excitement described above include a sense of self-confidence in their own ability. Various descriptions of self-confidence were central to the remarks in the student summaries as expressed in the following quotes: ‘I think I will be able to accomplish the task because I am very determined to succeed’. This quote illustrates the self-confidence of students anticipating their ability to carry out the activism. Their self-confidence is influenced by their understanding of the importance of teamwork as expressed in the following students’ words: ‘Team, collaboration, that we can be together and not alone all the time, that can help us with the project’. The weight the students placed on teamwork as part of their ability to meet their activism goals can be elicited in these two quotes.

Another factor that affects the students’ sense of self-confidence is their past experience, as some students point out: ‘We spoke in front of an audience in previous years and then it went really, really well’. In their remarks, the students emphasize their positive experience of presenting information to an adult audience. A further factor that helped create personal self-confidence was the encounter with Mayaan, the tenth-grade student from the youth climate protest, who provided a role model for the students. A high number of students mentioned this meeting as important:

Maayan raised our awareness … she talked about how she does it and how we can do it … the meeting with her really helped. I want to do it like her.

C.2 Student Concerns. Along with the positive feelings expressed by the students toward activism at the community level there were also concerns among some of the students. The concern was related to the lack of cooperation from other students at the school, as expressed in the words of the following student: ‘I feel a lot of fear that the children will not cooperate with us.’

Process D: students’ feelings at the end of the year

From the letters the students wrote to the Minister of Education, transcripts from the focus groups, and drawings with explanations, it can be discerned that the students did not see their failure to implement community-level activism as a failure. They justified the lack of completion of all projects as being due to a lack of time. At the same time, two main categories emerged. The need to continue the activism and its expansion (D.1), and the fear of the phenomenon of climate change (D.2).

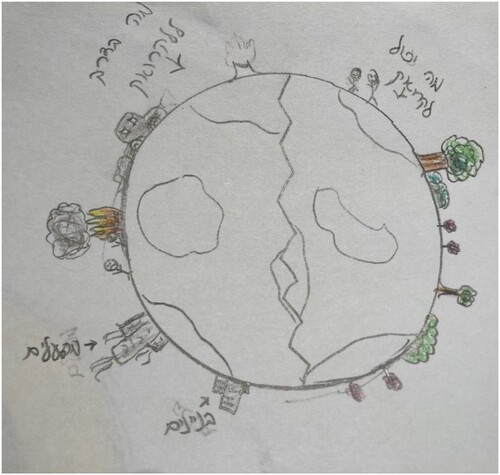

D.1 Continuity of the Activism. The students recommended the CCE program continued as part of the school curriculum: ‘It is very important that this program continues in school’. Students also attested to the fact that the opportunity to be involved in practical activism activities is essential for long-term learning: ‘Our experience is very important, if we only learn — we will forget; here we do, I will remember it for a long time … we must continue with this activism’. As part of their activism, students believe they can influence climate change: ‘Even if each of us does something small it has a very big impact, turn off the light, stop with disposables, collect waste — it's very important — we are many children and if we do, we influence and reduce climate change … therefore, the project must continue’. The students believe in themselves and think they have the power to change as can be seen in .

Figure 8. The earth is divided. To the right there are trees, shrubs and happy children (in green colors) and next to it is written, ‘What could have happened’. On the left there are buildings and factories (in black) and a bonfire (in yellow) with the text, ‘What is going to happen’.

The students also recommended extending the program to more classes: ‘I think it is worthwhile to continue with the program, it is even worthwhile to expand the program, even for children from fourth grade’.

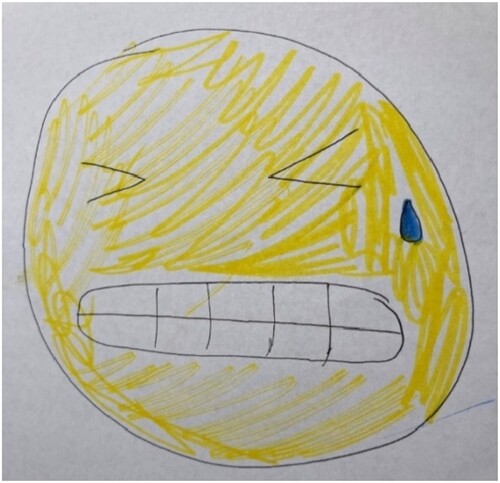

D.2 The Fear of Climate Change. Despite all that was said by the students, including their positive feelings and the belief in their ability to reduce climate change, the fear of climate change remains (). As one student said: ‘I am afraid of what if we [humans on earth] do not change our behaviour]’.

Figure 9. An example of a drawing that exemplifies the students’ feelings toward climate change (at the end of the year).

The apprehension shown in Drawing 4 is similar to the apprehension that was expressed by many of the students, even at the beginning of the CCE program. In this respect, it appears that there is no change in the students’ negative feelings toward the phenomenon.

Discussion

This research was focused on sixth grade children’s experiences of a CCE program in a school in Northern Israel. One of the main findings from this research project is the positive feedback the students provided in relation to how much they learnt as a result of the practical and hands-on modules of the program. This is because the CCE program was not based on theoretical knowledge regarding climate change alone, but was instead designed to give sixth-grade students as much practical experience as possible through the activism component of the program (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020).

It is clear from the research that the self-efficacy of the sixth-graders was initially accompanied by apprehension. After several attempts, however, even if not all of them were successful, there was a sense of success and a positive feeling toward leading environmental activism in the future. Therefore, the general picture that emerged from the students’ responses is that of a positive feeling of success. An increase in the feeling of one's abilities following successful experiences is recognized in the literature (Chawla Citation2020; Chawla and Cushing Citation2007).

In this CCE program, the activism activities were not based on recycling processes alone, which is a common learning activity in schools (van de Wetering et al. Citation2022). Instead, the activism that the students engaged in was diverse, and included various processes designed to give them the feeling of positively influencing and helping to reduce their impact on climate change.

The research also found that parents and other adults, and the provision of personal examples from various sources, were important to the students’ success in learning about climate change. The sixth-grade students testified to the importance of community support and teamwork in their positive feelings toward the activism experience, which is also noted in the literature (McDonald-Harker, Bassi, and Haney Citation2022; O’Malley Citation2015). In addition, the students indicated that meeting a role model, a student four years older than them, was significant for them and contributed to their ability to develop the feeling of being able to act for the environment. Observing a role model is well known as contributing to the development of a sense of competence (Bandura and Cherry Citation2020).

Parents’ opposition did not prevent the students from insisting on carrying out their activism activities and not giving up on the experience. The students’ continued activity in this context, was an important and unplanned by-product of the CCE program. The students proved that they have the confidence to act against adults who oppose their pro-environmental activities, even if only partially. In this way, the research thickens the literary information base that claims that children have the potential to influence their parents (Lawson et al. Citation2019), thereby contributing to the professional literature.

It appears, however, that the repeated experience of environmental activism did not become an established routine in students’ lives. For example, the students indicated that freedom or playing outside made them forget the need to maintain environmental activism. It is possible that the students’ own recommendations to expand the activist activity to lower grades and continue experimenting with it is the answer to turning activism into a way of life. The students’ overall response and the results of this study only reinforce the claim that CCE should be a long, continuous process, and that it should include as many different activist experiences as possible (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020). This is because as experience in a certain activity increases, the feeling of ability becomes more durable (Fitchett et al. Citation2018; Ma, Cavanagh, and Mcmaugh Citation2022).

As with other studies (e,g., Martin et al. Citation2022), the students indicated that they are still afraid of climate change. They are afraid because they have acquired new knowledge, at the same time as being exposed to the experiences related to activism. At the end of the CCE program the students understood that a global change in human behavior is essential in order to reduce the effects of climate change. In addition, the students revealed, indirectly, that they also acquired knowledge. This combination is important when teaching about climate change (Littrell et al. Citation2020). The students acquired knowledge by being actively engaged in the program (which was based on student-centred learning), through studying with their peers, and by having conflicts with their parents. This is reflected in their emotional reactions evidenced in the data (Barber and Haney Citation2016; McDonald-Harker, Bassi, and Haney Citation2022). Therefore, knowledge was acquired through different pedagogical processes, which aligns with the literary recommendations that different pedagogies are needed in teaching climate change effectively (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020).

Conclusions

Although it only involved two classes of sixth-graders in a single school, this study illuminates, with all the necessary caution, that climate change can be studied at the elementary school age (Li and Monroe Citation2019; Walsh and Cordero Citation2019). The study also reveals, however, that it is not easy to allay students’ fears about the effects of climate change (Dunlop and Rushton Citation2022). The students were not indifferent to the subject, as found in other parts of the world (O’Brien, Selboe, and Hayward Citation2018). In the case of this study, the students were willing to work to reduce the effects of climate change through the adoption of different behaviors within their means, not only through recycling, which is mainly reported in the literature (van de Wetering et al. Citation2022). The students took part in actions which they recognized as having a direct impact on the environment (Trott Citation2021). To encourage students to adopt daily activism (Taylor Citation2019) as a positive lifestyle change in the future, it is recommended they are encouraged to repeatedly experience successful activism, and not only twice, as in this particular CCE program (Fitchett et al. Citation2018; Ma, Cavanagh, and Mcmaugh Citation2022). It is also recommended that students’ experiences be accompanied by achievable goals, thus helping to instill hope among students rather than despair (Ojala Citation2012; Stevenson and Peterson Citation2016). It is also recommended that teamwork be emphasized among students, along with being introduced to positive role models, who are essential for increasing the students’ self-efficacy and resolve to act for the environment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bandura, A. 1982. “Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency.” American Psychologist 37 (2): 122–147. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122.

- Bandura, A. 2006. “Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales.” In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. Vol. 5, edited by F. Pajares, and T. Urdan, 307–337. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

- Bandura, A., and L. Cherry. 2020. “Enlisting the Power of Youth for Climate Change.” American Psychologist 75 (7): 945–951. doi:10.1037/amp0000512.

- Barber, K., and T. Haney. 2016. “The Experiential gap in Disaster Research: Feminist Epistemology and the Contribution of Local Affected Researchers.” Sociological Spectrum 36 (2): 57–74. doi:10.1080/02732173.2015.1086287.

- Beazley, H., L. Butt, and J. Ball. 2018. “‘Like it, Don’t Like it, you Have to Like it’: Children’s Emotional Responses to the Absence of Transnational Migrant Parents in Lombok, Indonesia.” Children's Geographies 16 (6): 591–603. doi:10.1080/14733285.2017.1407405.

- Bleazby, J., S. Thornton, G. Burgh, and M. Graham. 2022. “Responding to Climate Change ‘Controversy’ in Schools: Philosophy for Children, Place-Responsive Pedagogies & Critical Indigenous Pedagogy.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 0 (0): 1–13. doi:10.1080/00131857.2022.2132933.

- Chawla, L. 2020. “Childhood Nature Connection and Constructive Hope: A Review of Research on Connecting with Nature and Coping with Environmental Loss.” People and Nature 2 (3): 619–642. doi:10.1002/pan3.10128.

- Chawla, L., and D. F. Cushing. 2007. “Education for Strategic Environmental Behavior.” Environmental Education Research 13 (4): 437–452. doi:10.1080/13504620701581539.

- Dunlop, L., and E. Rushton. 2022. “Putting Climate Change at the Heart of Education: Is England’s Strategy a Placebo for Policy?” British Educational Research Journal, 1083–1101. doi:10.1002/berj.3816.

- Eldén, S. 2013. “Inviting the Messy: Drawing Methods and ‘Children’s Voices.” Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark) 20 (1): 66–81. doi:10.1177/0907568212447243.

- Fitchett, P., C. McCarthy, R. Lambert, and L. Boyle. 2018. “An Examination of US First-Year Teachers’ Risk for Occupational Stress: Associations with Professional Preparation and Occupational Health.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 24 (2): 99–118. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1386648.

- Flowers, A., J. Carroll, G. Green, and L. Larson. 2015. “Using Art to Assess Environmental Education Outcomes.” Environmental Education Research 21 (6): 846–864. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.959473.

- Foss, A. 2018. “Divergent Responses to Sustainability and Climate Change Planning: The Role of Politics, Cultural Frames and Public Participation.” Urban Studies 55 (2): 332–348. doi:10.1177/0042098016651554.

- Gal, A. 2022. “Puzzle Pieces but Not the Big Picture—How Students from a Green School Perceive the Environmental Crisis from Teachers’ Point of View.” Journal of Experiential Education, doi:10.1177/10538259221115580.

- Hemming, P. 2007. “Renegotiating the Primary School: Children’s Emotional Geographies of Sport, Exercise and Active Play.” Children's Geographies 5 (4): 353–371. doi:10.1080/14733280701631817.

- Hornsey, M., C. Chapman, and D. Oelrichs. 2022. “Why it is so Hard to Teach People They Can Make a Difference: Climate Change Efficacy as a non-Analytic Form of Reasoning.” Thinking & Reasoning 28 (3): 327–345. doi:10.1080/13546783.2021.1893222.

- Hungerford, H., and T. Volk. 1990. “Changing Learner Behavior Through Environmental Education.” The Journal of Environmental Education 21: 8–21. doi:10.1080/00958964.1990.10753743.

- IPCC. 2022. Sixth assessment report: Summary for policymakers headline statements. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/resources/spm-headline-statements.

- Jones, C. A., and A. Davison. 2021. “Disempowering Emotions: The Role of Educational Experiences in Social Responses to Climate Change.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 118: 190–200. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.11.006.

- Kollmuss, A., and J. Agyeman. 2002. “Mind the Gap: Why do People act Environmentally and What are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior?” Environmental Education Research 8 (3): 239–260. doi:10.1080/13504620220145401.

- Kustatscher, M. 2017. “The Emotional Geographies of Belonging: Children’s Intersectional Identities in Primary School.” Children's Geographies 15 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1080/14733285.2016.1252829.

- Lawson, D., K. Stevenson, M. Peterson, S. Carrier, R. Strnad, and E. Seekamp. 2018. “Intergenerational Learning: Are Children key in Spurring Climate Action?” Global Environmental Change 53: 204–208. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.002.

- Lawson, D., K. Stevenson, M. Peterson, S. Carrier, R. Strnad, and E. Seekamp. 2019. “Children Can Foster Climate Change Concern among Their Parents.” Nature Climate Change 9: 458–462. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0463-3.

- Li, C., and M. Monroe. 2019. “Exploring the Essential Psychological Factors in Fostering Hope Concerning Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 25 (6): 936–954. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1367916.

- Linneberg, M., and S. Korsgaard. 2019. “Coding Qualitative Data: A Synthesis Guiding the Novice.” Qualitative Research Journal 19 (3): 259–270. doi:10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012.

- Littrell, M., C. Okochi, A. Gold, E. Leckey, K. Tayne, S. Lynds, V. Williams, and S. Wise. 2020. “Exploring Students’ Engagement with Place-Based Environmental Challenges Through Filmmaking: A Case Study from the Lens on Climate Change Program.” Journal of Geoscience Education 68 (1): 80–93. doi:10.1080/10899995.2019.1633510.

- Littrell, M., K. Tayne, C. Okochi, E. Leckey, A. Gold, and S. Lynds. 2020. “Student Perspectives on Climate Change Through Place-Based Filmmaking.” Environmental Education Research 26 (4): 594–610. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1736516.

- Lubell, M. 2002. “Environmental Activism as Collective Action.” Environment and Behavior 34 (4): 431–454. doi:10.1177/00116502034004002.

- Ma, K., M. Cavanagh, and A. Mcmaugh. 2022. “Sources of pre-Service Teacher Self-Efficacy: A Longitudinal Qualitative Inquiry.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 00(00): 1–16. doi:10.1080/02188791.2022.2136140.

- Manni, A., K. Sporre, and C. Ottander. 2017. “Emotions and Values - a Case Study of Meaning-Making in ESE.” Environmental Education Research 23 (4): 451–464. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1175549.

- Martin, G., K. Reilly, H. Everitt, and J. Gilliland. 2022. “Review: The Impact of Climate Change Awareness on Children's Mental Well-Being and Negative Emotions – a Scoping Review.” Child and Adolescent Mental Health 27 (1): 59–72. doi:10.1111/camh.12525.

- McDonald-Harker, C., E. Bassi, and T. Haney. 2022. ““We Need to Do Something About This”: Children and Youth’s Post-Disaster Views on Climate Change and Environmental Crisis.” Sociological Inquiry 92 (1): 5–33. doi:10.1111/soin.12381.

- Mostafavi, A. 2021. “Architecture, Biometrics, and Virtual Environments Triangulation: A Research Review.” Architectural Science Review, doi:10.1080/00038628.2021.2008300.

- O’Brien, K., E. Selboe, and B. Hayward. 2018. “Exploring youth activism on climate change: Dutiful, disruptive, and dangerous dissent.” Ecology and Society 23 (3): 1–13. doi:10.5751/ES-10242-230301.

- Ojala, M. 2012. “Regulating Worry, Promoting Hope: How do Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Cope with Climate Change?” International Journal of Environmental & Science Educati 7 (4): 537–561. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ997146.

- Ojala, M. 2015. “Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations with Environmental Engagement and Student Perceptions of Teachers Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation.” The Journal of Environmental Education 46 (3): 133–148. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1021662.

- O’Malley, S. 2015. “The Relationship Between Children’s Perceptions of the Natural Environment and Solving Environmental Problems.” Policy and Practice: A Developmental Education Review 21: 87–104. https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-21/relationship-between-childrens-perceptions-natural-environment-and-solving.

- Onwuegbuzie, A., R. Frels, and E. Hwang. 2016. “Mapping Saldaňa’s Coding Methods Onto the Literature Review Process.” Journal of Educational Issues 2 (1): 130–150. doi:10.5296/jei.v2i1.8931.

- Orhan, M. 2022. “Investigation Into Popular Science Books as Children’s Literature in Terms of Sustainable Environment and Climate Change.” Journal of STEAM Education 5 (1): 68–87.

- Rousell, D., and A. Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles. 2020. “A Systematic Review of Climate Change Education: Giving Children and Young People a ‘Voice’ and a ‘Hand’ in Redressing Climate Change.” Children's Geographies 18 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1080/14733285.2019.1614532.

- Rushton, E., and N. Walshe. 2022. “Climate Change, Sustainability and the Environment: The Continued Importance of Biological Education.” Journal of Biological Education 56 (3): 243–244. doi:10.1080/00219266.2022.2116843.

- Saldaña, J. 2014. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: SAGE Publications. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Stevenson, K., and N. Peterson. 2016. “Motivating Action Through Fostering Climate Change Hope and Concern and Avoiding Despair among Adolescents.” Sustainability 8 (6): 6–10. doi:10.3390/su8010006.

- Taylor, S. 2019. Ecopiety: Green Media and the Dilemma of Environmental Virtue. New York: NYU Press.

- Tayne, K., M. K. Littrell, C. Okochi, A. U. Gold, and E. Leckey. 2021. “Framing Action in a Youth Climate Change Filmmaking Program: Hope, Agency, and Action Across Scales.” Environmental Education Research 27 (5): 706–726. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1821870.

- Trott, C. D. 2021. “What Difference Does it Make? Exploring the Transformative Potential of Everyday Climate Crisis Activism by Children and Youth.” Children's Geographies 19 (3): 300–308. doi:10.1080/14733285.2020.1870663.

- Trott, C. D. 2022. “Climate Change Education for Transformation: Exploring the Affective and Attitudinal Dimensions of Children’s Learning and Action.” Environmental Education Research 28 (7): 1023–1042. doi:10.1080/13504622.2021.2007223.

- van de Wetering, J., P. Leijten, J. Spitzer, and S. Thomaes. 2022. “Does Environmental Education Benefit Environmental Outcomes in Children and Adolescents? A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 81 (February 2021): 101782. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101782.

- Vergunst, F., and H. Berry. 2022. “Climate Change and Children’s Mental Health: A Developmental Perspective.” Clinical Psychological Science 10 (4): 767–785. doi:10.1177/21677026211040787.

- Walker, C. 2017. “Embodying ‘the Next Generation’: Children’s Everyday Environmental Activism in India and England.” Contemporary Social Science 12 (1–2): 13–26. doi:10.1080/21582041.2017.1325922.

- Walsh, E., and E. Cordero. 2019. “Youth Science Expertise, Environmental Identity, and Agency in Climate Action Filmmaking.” Environmental Education Research 25 (5): 656–677. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1569206.

- Yin, R. K. 2006. Case Study Reserach - Design and Methods. Second Edition. London: SAGE Publications.

- Zainal, Z. 2007. “Case study as a research method.” Journal of Aging Studies 10: 281–294. doi:10.1016/S0890-4065(96)90002-X.

Appendix 1.

Structure of CCE curriculum, including details of each stage of the study program and recommended allocation of hours