ABSTRACT

Worlding has been positioned as one way of considering how to attend and adapt to new imaginings of humanity in relation to other entities. In an act of living in places with other nonhuman beings, worlding offers a mode for naming these new spaces as central to a child's world-making. In this article, we explore the importance of noticing the ethics for staying with the trouble of worlding with children. This post-qualitative piece ruminates on the emergence of worlding as a theoretical concept and a methodology for considering worlding but not only. The first part of the paper asks: What is worlding? Are their moments of ethical discomfort in worlding? How can worlding unfold a space for undoing and unknowing? The second part of the paper then explores worlding possibilities through stories linked by the sea where fish and whales work with us to disrupt, reconfigure, and uncouple ethics of ‘worlding’ but not only. A series of ethical possibilities close the paper. The ethics of ongoingness and enchantment become a way to consider worlding but not only, a place for an unfolding of the unknowing and undoing where we can consider the ongoing, extending worlding as shared flourishing.

Introduction

The world is in ecological crisis and, if our species does not survive the crisis, it will probably be due to our failure to imagine and work out new ways to live with the earth, to rework ourselves and our high energy, high consumption, and hyper instrumental societies adaptively … We will go onwards in a different mode of humanity, or not at all. - Val Plumwood, Feminist Ecophilosopher. (2007, 1)

Worlding as a theoretical concept and a methodology has proven to be a means for focussing on human relations and provides a way for exploring new human/nonhuman relations within a challenging ecological crisis (Haraway Citation2008). Worlding has also been helpful in ecological knowing and post-qualitative research with children by bringing nonhuman beings into a new focus with humans (Taylor and Guigni Citation2012; Pacini-Ketchabaw and Taylor Citation2015; Malone Citation2019). Nxumalo and Pacini-Ketchabaw in the earlier forming of the worlding work with children noted ‘within a common world approach to childhood, the overarching question becomes how to stay with the trouble (Haraway Citation2008) that multispecies relations bring in the era of the Anthropocene. This central question has clear political and ethical framings’ (Nxumalo and Pacini-Ketchabaw Citation2017, 1416, their italics). This ‘common world’ approach explored by Nxumalo and Pacini-Ketchabaw (Citation2017) was posited as a means for responding to children and other beings becoming with each other by decentring the human subject through mostly a disruption of human exceptionalism and an unsettling of binaries. In early childhood education, worlding as means to describe multispecies relations was also emerging as one way for supporting and enriching children’s ecological and sensorial knowing (Malone Citation2019; Osgood Citation2021).

While the authors recognise worlding with children and their world supports potential thriving futures, we lean away from offering it as the sole answer to Plumwood’s call for ‘a different mode of humanity’. Specifically, we seek to ruminate with the practice of ‘worlding’ in the posthuman era and play with it, to view it still as an emerging not static ‘thing’. As education continues as a key component for remaking humans in the shadow of the ecological crisis (see Sobel Citation2006; Pacini-Ketchabaw and Taylor Citation2015; Green and Somerville Citation2015; Vladimirova Citation2021), it is in this place that we come together to rummage through bags of our own stories of ‘worlding immersions’ to ruminate on extending worlding possibilities. As a post-qualitative paper, we continue with the writings of Donna Haraway but to imagine ourselves in a future ecosystem grappling with fresh eyes to expand our repertoire we add to our thinking with philosophers such as Marisol de la Cadena, Jane Bennet, Girt Biesta and Michael Smith.

The paper starts with some key questions ruminating in our thinking: What is worlding? Where is worlding unfolding and in what new ways? The second part explores these various unfoldings in our own research where we have theorised human/nonhuman relations with ecological stories linked by children, the sea, fishes, and whales. We attempt in theorising our ‘worlding immersions’ to uncouple ‘worlding’ as an approach with a settled nature, a predicable mode but wonder what perchance is available by opening new spaces. This is where the unknowing and undoing come into our thinking of a worlding but not only.

We close the paper with a series of ethical possibilities to frame new spaces. Ongoingness and enchantment become a starting point for an unfolding of worlding which is always in a space of unknowing and undoing.

What is worlding?

Worlding can be many things. It is often described as feminist and posthuman/new materialist literature particularly within childhood studies, as a methodological approach to understand and investigate children ‘being-in and being-with complex entangled worlds’. Beyond shaping how we do research, worlding is often used to explain certain characters and principles for storing children’s lives as experiences and encounters pointing to relationally rather than disconnection (see Taylor and Guigni Citation2012; Malone Citation2019).

Worlding as an analytical concept embraces a means for describing children’s ‘being worldly with’ other nonhuman beings while resisting sentimental romanticising of these child-world relations as universal or positioning ‘nature’ as an object of goodness (Taylor and Guigni Citation2012). While it is acknowledged worlding will be different depending on the context of research, several characteristics, and principles of worlding have been proposed. For example, Jayne Osgood’s presentation on worlding posits worlding is an ‘immersive, embodied, affective and sensory approach to investigating the world and children’s connected place to their worlds and everything that’s in the world’ (Osgood Citation2021). It is positioned as the means for reappraising who we are as species by considering the complexity of relations we have with all other beings and the planet. Responding to these principles or characteristics, our paper opens space to consider, can ‘worlding’ become more than a response to child/world relations? And while the theoretical focus tends to be on children worlding with worlds, we question when decentreing the human, we need to further ask how is the world worlding with children?

Worlding, but not only?

Early in the essay When Species Meet Haraway (Citation2008) wondered about the ‘affect’ of human beings on other beings, and how we might become together in this unavoidable interface of affect. She came to the notion of a relationship as becoming with and noted how this moment of infolding is not an interface, but an infolding of becoming worldly. She wrote ‘I like the word infolding better than interface to suggest the dance of world making encounters. What happens in the folds is what is important. Infoldings of the flesh are worldly embodiment’ (Haraway Citation2008, 250).

Folds hide things. Some parts we can see and some we can’t. What is worlding here is partially knowable and partially obscured. For Haraway to be in relation with companion species was about responding and respect through paying attention ‘species interdependence is the name of the worlding game on Earth’ (2008, 19). While paying attention we will find there are surfaces on display, but we won’t know all that is going on. We need to be comfortable with the discomfort of the unknowing.

Marisol de la Cadena later drawing from the work of Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing, wrote of Haraway’s use of the concept of worlding in this way:

I use the concept to refer to practices that create (forms of) being with (and without) entities, as well as the entities themselves. Worlding is the practice of creating relations of life in a place and the place itself. If it is worlding, it is worlding, but not only. (de la Cadena Citation2015, 291–292)

… the kangaroo girl breaks with the human group and hops toward the mob, as she bodily enacts becoming kangaroo, is she called into a transspecies mode of intersubjectivity? Is she entering a kind of bodily enacted “otherworldly conversation”? Is this an example of the queer kin worlding that Haraway (Citation2008) talks about? (Pacini-Ketchabaw and Taylor Citation2015, 59)

(t)hese worlding practices, though, have effects and implications, and the question for early childhood pedagogies to grapple with is that some worldings world worlds in which, or with which, we do not want to live, or worlds that do not let us live, or that let some live and not others. (59)

Troubling worlding

In this paper as authors and researchers of childhoods we seek to explore the complexities of affective and potentially ethical forces of worlding events. What if, for instance, worlding begins with bodies, bodies knowing place (Somerville Citation1999), and where bodies are in places with kin (Haraway Citation2008). If this is where our experience of worlding emanates and ruminates with the deepest affect doesn’t where bodies are located in our worlding need more focus? Being with our bodies in places, like Somerville (Citation1999) attends in Body/landscape journals, allows for opportunities and possibilities to consider the politics of bodies and the ethics of being in a country on landscapes, seascapes, and atmospheres. David Abram in his sensorial writing on humans becoming animal entices us to consider bodies that are themselves a kind of place:

Our body is altered and transformed as it moves through different lands. If this is so, it is because the body is itself a kind of place – not a solid object but terrain through which things pass, and in which they sometimes settle and sediment (Abram Citation2010, 230).

A decade ago, when worlding was described as a methodological approach to understanding and investigating children ‘being in the world’ (Taylor and Guigni Citation2012), the focus was mostly on how worlding as an analytical concept could embrace a ‘being worldly with’ other nonhuman entities (Taylor and Guigni Citation2012). This view of worlding emerging from Haraway’s queering of kin in When species meet (2008) inspired many childhood researchers to consider ways theoretically to embrace a relational and ethical approach to worldly encounters. This relationality generated an alternative way to know a child’s relationship with more-than-human others beyond resource-based utilitarianism, or the human-centred approaches supporting subject/object binary. This relationality engaged with the political imperative of grappling with ‘dilemmas and tensions that inevitably arise when we co-inhabit with others’ and sought to consider ‘grappling encounters as “worldings” differences’ (Taylor and Guigni Citation2012, 113). The focus was not so much on where bodies were but what bodies did when in these worlding encounters. Smith argues what happens between humans and other beings aren’t like bridges but connections with/in bodies and by:

(e)mphasising such connections begins to deconstruct the ontological certainties and absolute distinctions that have supported various forms of human exceptionalism and exceptionalism. We are ineradicably hybrid beings inhabiting hybrid geographies. (Smith Citation2013, 29)

Haraway writing on worlding in her seminal book Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Cthulucene (2016) surmises worlding is carrier bag-like, brimming with messy stories. Worlding here is not a thing to do, but a way to hold whatever is happening, whatever is at play, now, before and after. If we take up this messy carrier-bag kind of worlding or holding space for kin bodies, for children, other beings, and for ourselves to collaborate, Haraway offers we are making room for moments of relation to bend toward ongoingness (Haraway’s term). Ongoingness, so worlding doesn’t rest and isn’t certain. Jayne Osgood in the worlding of lichen in an ongoing pandemic world troubles the presence of lichen as a means to ‘tell us about the absence of humans’ (2022, 61). Worlding as absence rather than the presence of humans provides a view of multispecies flourishing outside of human intervention (Osgood Citation2022). Smith (Citation2013, 34) alludes to this in his ontological thinking with posthuman ecological communities drawing on the writing of Jacob von Uexküll in his book A Stroll through the Worlds of Animals and Men, where Uexküll reveals the worlds of ticks he writes, ‘beings appear to us, but they never just appear and they never appear just to us humans. Beings have (sensed and unsensed) effects on us, but they never just have effects on us’. These stories of worlding in the absence of humans continue to move us. Kohn reminds us, these stories of uneasy assemblages are by no means stories of comfort, joy, or a life preserved. They flourish as ‘(s)tories of becoming-with, of reciprocal induction, of companion species whose job in living and dying is not to end the storying, the worlding’ (Kohn Citation2018, 119). ‘Living and dying with kin is not to end the storying, the worlding’ (Kohn Citation2018, 119). We are intrigued by this notion by Smith (Citation2013), Kohn (Citation2018) and Osgood (Citation2022) and it begins a new rumination on our thinking of worlding.

This time we consider the work of Jane Bennet (2001) and her questioning of the relationship between enchantment, attachment, and care. In her book The Enchantment of Modern Life she argues ‘it is important because the mood of enchantment may be valuable for ethical life’. She writes if ‘popular psychological wisdom, has it that you have to love yourself before you can love another, my story suggests that you have to love life before you can care about anything’ (Bennett Citation2001, 4). ‘To be enchanted’, according to Bennett (Citation2001, 4),

is to be struck and shaken by the extraordinary that lives amid the familiar and the everyday. Starting from the assumption that the world has become neither inert nor devoid of surprise but continues to inspire deep and powerful attachments.

Unknowing and undoing worlding

Haraway’s (2016) worlding engages us in finding life in messy questions, in the unknowings that undo possibilities to support a cobbling together of new possibilities Learning to be worldly ‘from grappling with, rather than generalizing from, the ordinary’ (Haraway Citation2016, 3). Therefore, worlding is not something we can name, a thing but a space to ruminate within. Worlding itself therefore always involves unknowing and undoing. Inspired by her engagement with Ursula Le Guin’s science fiction and speculative fictions (2016) Haraway’s carrier bag we believe invites us to take comfort in unknowing and undoing.

Just last week I was walking along the beach close to my house when something caught my attention. There was a large group of seagulls close to shore noisily diving, feeding, jostling together on top of what looked like a large clump of seaweed. As I got closer, I could see what I had mistaken for seaweed was a large school of fish fashioning almost a dance like murmuration just under the water. I was so enticed by the beauty of this I entered the water and joined them iPhone in hand, mesmerised I immerse myself in a worlding relation becoming-with, being bird, ocean, fish … Am I worlding with them I wonder?

The stories we have collected to explore these ruminations of worlding as unknowing and undoing are as St Pierre notes ‘concerned not with what is but what is not yet, to come.’ (St Pierre Citation2021, 163). In a post-qualitative paradigm unfolding, we are exchanging and experimenting (Charteris et al. Citation2019) – writing in the not yet. We understand the lapping waves of stories and theory here as partial possibilities emerging with worlding.

Originally, to support the emergence we (the authors) talked back and forth in messenger sharing stories with common threads. The extracted storylines taken from the whole story, are deliberately partial to disrupt in order to find diffractions of bodies, place and time which are mostly intact (Crinall, Citation2016; Malone, Citation2016, Citation2019). This academic writing as ‘patchy affairs’ allows us to ‘hold ourselves accountable to our inherited histories’ (Kohn Citation2018, 51), by being as embodied as we can to mustering a practice (Marakem Citation2021). The research as ruminating is revealing the slow, ongoing, and unending (Gumbs Citation2020) practice of upending the not yet, that which is coming. We are staying in the comfort of the unexpected, finding the questions in our worlding not the answers (Boutte and Jackson Citation2014).

Encounter: fish

We had a fish in a bowl in the classroom

Children became very attached to the fish, caring for it, cleaning the bowl, but it died

A parent who knew about fish told us, maybe the fish couldn’t breathe in the bowl

The bowl was too small

I felt guilty. The children asked me why did the fish die?

When I said maybe it couldn’t breathe, they wanted to know more

We decided to set up a science investigation exploring the question: how does a fish breathe? First, we went on an excursion to the beach

Children had many questions after the beach excursion

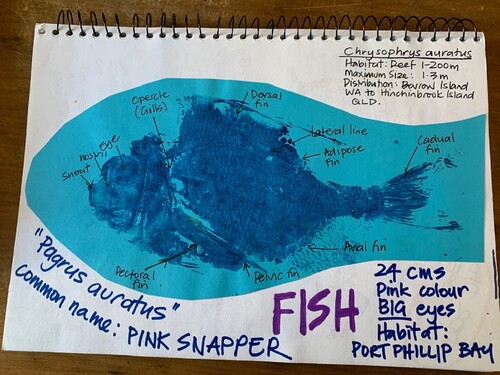

I brought some fish from the local fish shop into the classroom – so together we could be scientists to answer our questions

We looked closely at the fishy bodies

The children said it felt slimy

We use the body to print

We told fishy stories

Imagined what was inside

Then we cut it up

Blood oozed

Children covered eyes

Some poked at bits

Others walked away

“It’s disgusting”

“I don’t want to touch it”

“Makes me sad”

Historically an animal’s sentience has been a persuasive scientific barometer for determining whether certain animals should be afforded some ethical level of care and consideration. Eighteenth Century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham the moral question of sentience is not can an animal reason, or can they talk, but more can they suffer? Could children learn what animals to love and which to eat as worlding? When the teacher described the fish dissection in the classroom, the unfolding of where ethics might take us in our thinking of worlding was revealed.

One child asked, “do you eat fish?”

Yes, I said, do you?

No, she said blood and goo

It’s disgusting

Dead animals

It seemed like a good idea

Dissecting as a science lesson

I regretted it

Never again.

No more fish in a fishbowl

In a short video captured on my Iphone taken at an aquarium visit Wren who is just 2 years old mimics the slow fishy body as it moves through the watery glass. The fish moves to her, her body lowers closer and closer till only the glass separates them. The eyes of the fish catch hers. A fish gaze intensely waiting; seeking her attention. Eyes fixed on hers. Water, air, glass, and bodies intra-acting. Mesmerized, entranced both eyes are fixed; eyeballing; child-fish recognition; past tracings of ghostly beings passing through the clear glass watery spaces, separated bodies feeling all but heartbeats. The fishy body moves ever so gently in the water currents, but the eyes seldom leave the gaze. As sensorial beings, they seem to be communicating through their watchful worlding.

recognition can be fleeting

a moment where eyes meet eyes

entranced by the knowing

not wanting to look away

ancient time held in the longing

Do humans, as a species among other species, have a particular responsibility, in an ethical and historical sense, to sustain life? Who is privileged when young children learn about life-sustaining relationships across species and matter? What happens if the emphasis shifts from sustainability to flourishing?.

Encounter: whale

Today we cancelled our plans with scratchy throats and packed a basket for going to the beach to sketch and be with the whale. I felt so drawn and so did Edge. “I want to go closer. Come with me mum, closer.” River reached for a surgical mask from the glove box while I got the basket from the boot. When we reached the beach, she sat herself way away. I asked her why and she said – that smell and what if she explodes? won’t touch me here.” Edge wanted to touch a tooth so we circled around and noticed rose-patterns on the water’s edge.

‘Being singular-plural’ before the moment of proximity, and after the whale and child are already ‘beings-in-common’ (Nancy Citation1997). Before River sat herself away, or Edge’s want to go closer the posthuman notion sees them as already communities in the whale/human mode, when the whale washed ashore. River’s discomfort did not need our meddling to encourage her closer, to draw or touch, into a worlding event. That communities dissolve is natural too.

Later that month the same child who was repelled by the smell and was cautious of an exploding whale flesh, shared before going to sleep:

When I die, I want to be buried next to the sperm whale, mum.

This takes us to thinking before the advent of posthuman notions of ecological communities to Indigenous knowledge systems. de la Cadena’s writing with the Runa Kuna acknowledges a worlding but not that is a practice, what happens between bodies that become worldly and … is not exhausted by ecology and geography (2015, 292 added italics). Worlding, but not only may be useful to hold as a space for considering the ethic of what Duhn and Galvez (Citation2020) ask when we are shifting emphasis from sustainability to flourishing. A practice for being careful not to focus on worlding as the only way to understand human/nonhuman relations when with children and their worlds. To do so may risk sending worlding into environmental education as a form of colonisation posed by white people privileging themselves with a comfortable solution for tending human ongoingness while in reality those in our peripheral vision are struggling for existence and will have other worldly relations at work. Here again we commit to peering beyond ‘worlding’ and acknowledge knowledge that does exist outside geography and ecology to keep a bridge for more that can (not quite) trace all the hybrid sedimented infoldings of flesh that lifeful communities are made up of.

I’d like to touch her mum, Edge prompted me. A tooth, at least? Come with me, let’s touch, can I touch her tooth? Or take a tooth? I want to come back and dig up and take a tooth and bones, for necklaces. The Boonwurrung would.

We did ceremony and it was very special. The caves opened-up, cleared of sand that week. Boonwurrung would bury this whale in the dunes up there. Take all the bones and bits we could use. Not now though, we aren’t able to take, not even touch. (Steve Ulula Parker, Boonwurrung elder)

A sign on the cliff-side warns of pathogens to be wary of. We aren’t to touch either, Steve shared. The jaw and teeth were later dawn off to be sold at market, I didn’t want to tell you.

Being in the world with whale carries with it all the failings of white privilege and necessary queries into, can we undo them? Is this the question of our worlding?

These whale/Boonwurrung/child/beach bodies move as a place (Abram Citation2010) and a place without isolation from the disharmonies we are born of, entwined with and committed to practicing against. Beyond ‘objective’ positions of the binary kind the bones and teeth of the whale are vibrant matter that powerfully moves political positions. Though a whale tooth and a white child are so very different, they touch each other so very, very, intimately (Smith Citation2013, 3) and who knows what happens next?

Encounter: whales, fish and fishbowls

Have you read Whale in a Fishbowl – a story by Troy Howell and Richard Jones? Whale in a fishbowl is the story of Wednesday a whale who finds herself in an ‘obscene, disturbing, disconnected’ human worlding – trapped in a fishbowl in a city away from the blue. She learns from Piper, a small human she does not belong here; she belongs to the sea. She pines to find this an unimportant, unintentional life away from humans. To be in right relations she must find a way to get to the blue.

Whales use to be Elders on the land, flesh elders, but they moved into the sea to protect the fish and look after the food and medicines there. Most of the whales and fish were once Elders on the land and now they are Elders of the sea. Each and every one of them would have to hold the Lore of the seas. There is a time for them to come back. Then the message would get out and all the different clans and mobs would arrive to feast on the whale that had given up his life so Lore could be known. (Uncle Max Dulumunmun Harrison Citation2009, 142–143)

They wanted to at least be able to perform some sort of ceremony for that animal and we could do something that would allow us to fulfil our cultural responsibilities by burying part of that animal on-country. (Palmer and Poole, Citation2021, n.p.)

Thirteen years earlier a child draws the blueness of a blue whale he was hoping to become .

This is a blue whale. It is the biggest in the world. We need to stop people killing whales. I want to become a whale. I need to eat more. Blue is my favourite colour. My mum has two babies, so I need to look after myself- Dane, age 5.

Worlding with ethics of ongoingness and enchantment

In 2017 as the Common World collective scholars drew on the term ‘worlding,’ they sought:

to inquire into how environmental early childhood education in urban spaces might grapple with the feminist practice of ‘staying with the trouble’ (Haraway Citation2008) in this time of ecological challenges. [In response to] Feminist philosopher Donna Haraway [whom] explains that staying with the trouble entails continually questioning our responses and accountabilities and remaining curious about the ethical implications of certain acts of caring rather than taking them for granted. (Nxumalo and Pacini-Ketchabaw Citation2017, 1416)

An ethic of ongoingness

As ethic of ongoingness (see Virginia Held Citation2005) ruptures feminist responses into relations during decision-making and takes a moral pathway for the greater good. While Anna Vladimirova (Citation2021) in the morethanhuman context of process philosophies – draws an ethic of care beyond the human-centred toward care-in-between in her immersive video research with children in forest settings. An ethic of ongoingness holds spaces for beings to be repelled and disinterested in each other as well as to connect and care, while always mutually emerging for life and into death. Abram (Citation2010) proposes a kind of ethic of ongoingness that is a disintegrating malaise marking a disturbance though settling at times, that turns sedimentary, previous bodies – containers able to weather worlds disintegrating – into place bodies travelling on altering terrain (Abram Citation2010, 230).

Where children are also human beings being with other beings, reading of the fish murmuration and their disregard for ‘I’ comes with a disturbing awareness of how vulnerable these fish are in relation to us human beings when the disquiet is listened to. Coming out of the holding bag, thoughts, and ruminations spill into other possibilities. Together with the joy of fish untouched, alongside legs in water and moments to stop and watch, calm, and safe enough to take footage with Iphone in hand comes the sense that sometimes there is joy and disturbance.

Re-telling our stories here hints at an ethic of ongoingness where an ethical pedagogy allows a sense of joy in worldly relations yet also names the inevitable disturbances. Perhaps an ethic of enchantment alongside Abram’s ethic of ongoingness can allow for this?

An ethic of enchantment

Bennett’s enchantment troubles us and our stories too. Could we produce hints of an ethical pedagogy of enchantment that returns children to an inherent ‘mixed bodily state of joy and disturbance’ (Bennett Citation2001) into lives where they are watched over by a parent, carer or educator who holds the power to affect (their) worlding?

As an ant crawls across my arm, it is visible to my observations, I become attuned to its movements, tactile to my skin, I feel goose bumps rise, I shudder. As a sentient being the ant also coexists in this contemporaneous sensorial relation responding to my warmth, my movements, even to the chemical changes in my mood released through my skin.

Enchantment consists of a mixed bodily state of joy and disturbance, a transitory sensuous condition dense and intense enough to stop you in your tracks and toss you onto new terrain and to move you from the actual world to its virtual possibilities. (Bennett Citation2001, 111)

In this paper we have explored how worlding, but not only notices awkwardness and unease and holds space for children’s and educator’s bodies to become with other life and to ruminate there as an unfolding, to be affected by and to consider the ongoing. Michael Smith reminds us:

What appears to human beings is not all that appears and what affects human being directly is not all that effects, that what has significance in its appearance to, and effects on human’s beings, has different significance for other beings. (2013, 24)

… on returning home to upload the videos as the unseen is revealed – as human I may be naming this worlding but the fish, ocean and gulls are not worlding with me – they are surviving I am merely an unknown interruption, a pair of legs an obstacle, a disruption in this dance of survival – I write in response to watching the videos, I consider we are so unimportant in this moment to entities who live in our peripheral vision just under the surface living an unhuman life.

Ethics declaration

Data contained within this article were approved by Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee on 6/11/2018. The approval reference number and research study title: H12921 ‘Children’s bodies sensing ecologically: a study of pre-language children’s ecological encounters’.

Acknowledgement

This paper is written on the unceded lands and waterway edges of Wurundjeri and Boonwurrung Country, lands and waters that always was and always will be Aboriginal land. We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the lands where we work, learn and live, the Wurundjeri and the Boonwurrung People of the Kulin Nation. We celebrate the diversity of Aboriginal people and their ongoing cultures and connections to the lands, animals and waters of their Country.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abram, D. 2010. Becoming Animal. New York: Taylor and Francis Publishing Group.

- Bennett, J. 2001. The Enchantment of Modern Life: Attachments, Crossings and Ethics. Princeton, NJ: University Press.

- Blaser, M. 2014. “Ontology and Indigeneity: on the Political Ontology of Heterogeneous Assemblages.” Cultural Geography 21 (1): 49–58.

- Boutte, G. S., and T. O. Jackson. 2014. “Advice to White Allies: Insights from Faculty of Color.” Race Ethnicity and Education 17 (5): 623–642. doi:10.1080/13613324.2012.759926

- Braidotti, R. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Charteris, J., S. Crinall, L. Etheredge, E. Honan, and M. Koro-Ljungberg. 2019. “Writing, Haecceity, Data and Maybe More.” Qualitative Inquiry 26 (6): 571–582. doi:10.1177/1077800419843558

- Collective Intellectualities. 2021. “1 Gert Biesta - Philosophy of Education, Democracy, Creativity, Risk, and Subjectification”. YouTube. https://youtu.be/o3H7OWg0u-0.

- Crinall, S. 2016. What is (the) Matter-With-Data? The creative Practice Of Blogging Space, Place, Body Research. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Australian Association of Research in Education (AARE), Brisbane, 2014.

- Crinall, S. 2019. Sustaining Childhood Natures: The art of Becoming with Water. Singapore: Springer.

- Crinall, S., and M. Somerville. 2019. “Informal Environmental Learning: The Sustaining Nature of Daily Child/Water/Dirt Relations.” Environmental Education Research 26 (9): 1313–1324. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1577953

- de la Cadena, M. 2015. Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice Across Andean Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Duhn, Irish, and Sarita Galvez. 2020. “Doing Curious Research to Cultivate Tentacular Becomings.” Environmental Education Research 26 (5): 731–741. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1748176

- Green, M., and M. Somerville. 2015. “Sustainability Education: Researching Practice in Primary Schools.” Environmental Education Research 21 (6): 832–845. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.923382

- Gumbs, A. P. 2020. Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals Emergent Strategy Series. Edinburgh, UK: AK Press.

- Haraway, D. 2008. When Species Meet. London, UK: Minnesota Press.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Harrison, M. D. 2009. My People's Dreaming: An Aboriginal Elder Speaks on Life, Land, Spirit, and Forgiveness. FInch Publishing.

- Held, V. 2005. The Ethics of Care: Personal, Political and Global. UK: Oxford University Press.

- Hohti, R. 2021. “Minor Players, Worlding Encounters: The Common Worlds of Children and Animals: Relational Ethics for Entangled Lives.” Children's Geographies 19 (2): 255–257.

- Kohn, E. 2018. “Book Review: What Kind of World Can What Kind of we World: Staying with Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble.” Dialogues in Human Geography 8 (1): 99–101. doi:10.1177/2043820617739206

- Malone, K. 2016. “Reconsidering Children’s Encounters with Nature and Place using Posthumanism.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 32 (1): 42–56.

- Malone, K. 2018. “Co-mingling Kin: Exploring Histories of Uneasy Human-Animal Relations as Sites for Ecological Posthumanist Pedagogies.” In Animals in Environmental Education: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Curriculum and Pedagogy, edited by Teresa Lloro-Bidart, and Valerie Banschbach, 95–116. London: Palgrave Publishers.

- Malone, K. 2019. “Worlding with Kin: Diffracting Childfish Sensorial Ecological Encounters Through Moving Image.” Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy 4: 69–80. doi:10.1163/23644583-00401011

- Marakem, R. 2021. Notice the Rage, Notice the Silence. The On Being Project with Krista Tippett. https://onbeing.org/programs/resmaa-menakem-notice-the-rage-notice-the-silence/.

- Nancy, J,L. 1997. The Sense of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Nxumalo, F., and V. Pacini-Ketchabaw. 2017. “‘Staying with the Trouble’ in Child-Insect-Educator Common Worlds.” Environmental Education Research 23 (10): 1414–1426. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1325447

- Osgood, J. 2021. An Introduction to ‘Worlding’ in Early Childhood with Professor Jayne Osgood. CERS Middlesex University, YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = dJEALKMbHNM.

- Osgood, J. 2022. “From Multispecies Tangles and Anthropocene Muddles: What Can Lichen Teach us About Precarity and Indeterminacy in Early Childhood.” In Children and the Power of Stories, edited by C. Blyth, and T. Aslanian, 51–68. Singapore: Springer.

- Pacini-Ketchabaw, V., and A. Taylor. 2015. “Unsettling Pedagogies Through Common World Encounters: Grappling with (Post)Colonial Legacies.” In Canadian Forests and Australian Bushlands. In Unsettling the Colonial Places and Spaces of Early Childhood Education, edited by Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw, and Affrica Taylor, 43–62. New York: Routledge.

- Palmer, H., and F. Poole. 2021, March 24. Heart of Rare Blainville's Beaked Whale Buried in Beach as Part of Indigenous Ceremony, posted ABC website. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-24/beached-whale-carcass-in-coffsharbour-hear-buried-cultural/100025648?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web.

- Plumwood, V. 2007. “A Review of Deborah Bird Rose’s ‘Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation’.” Australian Humanities Review 42: 1–9. http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2007/08/01/a-review-of-deborah-bird-roses-reports-from-a-wild-country-ethics-for-decolonisation/.

- Rautio, P. 2017. “Thinking About Life and Species Lines with Pietari and Otto (Garlic Breath).” Trace: Finnish Journal for Human-Animal Studies 3: 94–102.

- Smith, M. 2013. “Ecological Community, the Sense of the World, and Senseless Extinction.” Environmental Humanities 2: 21–41. doi:10.1215/22011919-3610333

- Sobel, D. 2006. Place-based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities. Orion Society.

- Somerville, M. 1999. Body/Landscape Journals. Melbourne, Australia: Spinifex Press.

- St Pierre, E. 2021. “Why Post Qualitative Inquiry.” Qualitative Inquiry 27 (2): 163–166. doi:10.1177/1077800420931142

- Taylor, A., and M. Guigni. 2012. “Common Worlds: Reconceptualising Inclusion in Early Childhood Communities.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 13 (2): 108–119. doi:10.2304/ciec.2012.13.2.108

- Taylor, A., and V. Pacini-Ketchabaw. 2018. “Learning with Children, Ants, and Worms in the Anthropocene: Towards a Common World Pedagogy of Multispecies Vulnerability.” In Feminist Posthumanisms, New Materialisms and Education, edited by J. Ringrose, K. Warfield, and S. Zarabadi, 125–147. London: Routledge.

- Vladimirova, A. 2021. “Caring In-Between: Events of Engagement of Preschool Children and Forests.” Journal of Childhood Studies 46 (1): 51–71. doi:10.18357/jcs00202119326