ABSTRACT

Separate leisure spaces play an important part in children with disabilities’ everyday geographies, though little is known about how they are designed and organised or how children use them. This article contributes to the field of disabled children’s geographies (cf. Ryan, Sara. 2005. “‘People Don't do odd, do They?’ Mothers Making Sense of the Reactions of Others Towards Their Learning Disabled Children in Public Places.” Children's Geographies 3 (3): 291–305) by building on a three-year ethnographic study that explores a separate leisure space in Sweden for children (3-11 years) with disabilities such as ADHD and autism. The current article focuses on the ‘calm room’ within the facility, aimed at providing space for preventing and handling children ‘acting out’. By analysing this particular room, the study illuminates the ideas and assumptions about the children that went into designing the separate leisure space. Two dimensions of the room are analysed: (i) the design of the room, and (ii) children’s uses of the room.

The analysis demonstrates that children used the room for their own purposes, for example for resting, socialising or playing. When children’s uses of the room conflicted with what designers had planned for, tensions arose between the ideas about children’s needs that informed the design of the room and what the children needed or wanted during their visits. This demonstrates the importance of not having too rigid ideas about children with disabilities’ needs when planning and designing separate leisure spaces. It is suggested that one way of ensuring that children’s actual needs and desires are considered, rather than those assumed or imagined by adult designers, is by finding ways to include children in the design and planning processes.

Introduction

In a Children’s Geographies special issue editorial from 2010, Pyer et al. (Citation2010, 1) argue that ‘greater attention should be paid to the geographies of children and young people who are effectively marginalised as a consequence of their “disability”’. They state that while children’s place in geography has been established (cf. Holloway Citation2014), the visibility of children with disabilities remains at the margins. Consequently, children’s geographies need to begin to address the question of ‘disabled children in geographies with, for and of, children and childhood’ (Pyer et al. Citation2010, 1). Since then, several articles have addressed or examined these issues (e.g. Avramović and Žegarac Citation2016; Fernandes Citation2022; Stephens et al. Citation2017); however, little attention has been paid to children’s geographies in leisure contexts such as organised sport or leisure facilities (for exceptions, see Hodge and Runswick-Cole Citation2013). This article contributes to the study of disabled children’s geographies (cf. Ryan Citation2005) and provides insights into the children’s everyday geographies (cf. Holt Citation2004; Citation2007) by analysing a leisure space for young children with neuropsychiatric disabilities.

One way to organise leisure for children with disabilities is through separate provision, where membership and access are based on having certain diagnoses or difficulties (e.g. Goodwin and Staples Citation2005; Hodge and Runswick-Cole Citation2013). Access to separate leisure is stipulated in the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (CRPD), which states that State Parties shall ensure the opportunity to organise and attend disability-specific leisure activities (United Nations Citation2008, Article 30). In the context of summer camps, Goodwin and Staples (Citation2005, 159) argue that ‘segregated recreational camp programs’ have decreased due to ‘the ideology of inclusion’. This ‘ideology’ is mirrored in disability leisure literature, which mainly focuses on mainstream and inclusive leisure and aspects such as what makes inclusive leisure spaces accessible (cf. Black and Ollerton Citation2022; Jeanes and Magee Citation2012; Smart et al. Citation2018). However, follow-up studies on leisure access find that separate provision is necessary to ensure participation (The Swedish Agency for Participation Citation2020, 10). Separate spaces and periods of ‘segregated inclusion’ (Place and Hodge Citation2001, 395) are thus an important part in children with disabilities’ everyday geographies (cf. Hodge and Runswick-Cole Citation2013; Thompson and Emira Citation2011). Little is known, however, about aspects of separate leisure such as how it is organised or how children use it.

In this article, I focus on a separate leisure space aimed at children (3-11 years) with so-called ‘neuropsychiatric disabilities’ (e.g. ADHD, autism; this term is further explained in the terminology section) that I choose to call ‘The Panda’. The Panda is situated in a large Swedish city and was inaugurated in the spring of 2019 after a private initiator received project funding from a Swedish national fund. The leisure facility offers, for example, a two-storey jungle gym, a ball pit, wooden toy train sets, and a café section for coffee, drinks and snacks (referred to in Sweden as ‘fika’). Daily operations are organised around ‘play sessions’, where families book a time slot of either 1.5 or 2 hours to use the facility. Depending on the time and date, up to 3 or 6 children may visit at the same time. The children visit The Panda together with one or two parents and may also bring siblings with and without disabilities. Today, The Panda operates as part of an established Swedish youth organisation for sports and leisure and is funded partly by the local municipal and regional authorities.

To explore the topic of separate leisure for children with disabilities in a way that recognises the particularities of the children’s life conditions and experiences, I turn to disabled children’s childhood studies (Curran and Runswick-Cole Citation2014). This approach to childhood disability is rooted in three distinct starting points: first, to talk ‘with’ rather than ‘about’ children with disabilities; second, to put their voices and lived experiences at the centre of the research; and third, to challenge the hegemonic norms that surround the children’s lives. For the current study, this translates into a focus on the children and their activities at The Panda and conducting research ‘with’ rather than ‘about’ the children (Tiefenbacher Citation2023). Another important underpinning of this approach is to explore and make visible disabled children’s childhoods’ in different local and global contexts (Curran and Runswick-Cole Citation2014). Accordingly, it is responsive to different ways of understanding and representing childhood disability. Embodied and social aspects of disability are therefore recognised (cf. Holt Citation2007). In this study, I emphasise social aspects, as the study’s empirical site – The Panda - was built as a response to inaccessible mainstream leisure settings and activities. Moreover, my research interest lies in The Panda as a physical facility and how children use it, thus emphasising the interplay between the children and their surroundings. Therefore, the focus on social aspects of disability in the study is responsive to the setting of empirical inquiry and the research interest and questions.

The specific focus of the current article is a designated ‘calm room’ at The Panda. This room was designed to provide a retreat space to be able to prevent or manage children ‘acting out’. Thus, it builds on a specific idea of children with neuropsychiatric disabilities’ behaviours and needs and, by extension, how leisure spaces need to be adapted to provide meaningful leisure. The way that children use the room, however, does not always align with the designers’ plans. An analysis of the room can tell us more about the organisation and planning of separate leisure spaces and how children understand and use them. In this way, focusing on the calm room provides important insights into the designing and organising of separate leisure spaces.

In the article, I highlight two different dimensions of the calm room: the design of the room and the children’s uses of the room. I do this by analysing, on the one hand, the assumptions and ideas that informed the planning and design processes and, on the other, how children actually use the room. The analysis departs from the concepts of places for children and children’s places (Rasmussen Citation2004) and action possibilities (cf. Gibson Citation1979) and demonstrates that although this place for children was designed for particular purposes, these do not always align with how the room has come to be used by children. Analysing how children use the room reveals needs and preferences that were not planned for by the designers but that the room has come to accommodate. Focusing on children’s uses of these kinds of leisure spaces is, I suggest, one way of conducting research within the field of disabled children’s geographies (cf. Ryan Citation2005) which can help advance more accessible and inclusive leisure spaces that suit the children’s needs and desires.

Terminology

In research with and about persons with disabilities, the language and terminology used are a central concern, as they are closely linked to conceptualisations of and approaches to disability. Historically, identity-first language (‘IFL’, e.g. ‘disabled children’) has been used as part of medical understandings of disability, whereas a turn towards social understandings of disability brought with it a change in terminology to person-first language (‘PFL’, e.g. ‘children with disabilities’). In more recent years, IFL has come to be reclaimed by various disability movements and self-advocates (Bury et al. Citation2020) which means that both ways of writing are used. Consequently, there is a lack of consensus about what language is ‘correct’ (Botha, Hanlon, and Williams Citation2021). Shakes and Cashin (Citation2020, 227) suggest that the language used should be ‘contextually driven’ and based on an ‘awareness of the potential benefits and consequences of either person-first or identity-first language’. In a Swedish context, the use of PFL is firmly rooted in the Swedish disability movement and is thus preferred and used by advocacy groups such as Autism Sweden and agencies such as the Swedish Agency for Participation. To be responsive to the context in which the study is situated, I use PFL in this article.

Another aspect of the terminology concerns the term ‘neuropsychiatric disabilities’ (neuropsykiatriska funktionsnedsättningar). This is a Swedish umbrella term that encompasses ADHD, autism, Tourette’s syndrome and severe language impairments. This term is widely used by Swedish disability advocacy groups, such as Riksförbundet Attention and Autism Sweden. In other contexts, terminology such as ‘neurodiversities’ is preferred in order to emphasise that, for example, autism is one of many neurological variations and differences in the human population, rather than a disability (Runswick-Cole Citation2014). The umbrella term ‘neuropsychiatric disabilities’, however, is commonly talked about with reference to ‘disabilities’ rather than neurological variations. I would like to emphasise that when I am writing about children with neuropsychiatric disabilities, it is not my intention to label these neurodiversities as disabilities but instead, the language I use is responsive to the geographical context of the study.

Theoretical framework

Separate leisure spaces for children are places designed by adults for children; what Rasmussen (Citation2004) calls places for children. He uses the concept to explore children’s everyday places within the ‘institutionalized triangle’ (Rasmussen Citation2004, 156) and demonstrates that children create their own places within places for children, for example by using courtyard trees in new and unintended ways. For children with disabilities, daily life can also take place in separate spaces, such as separate leisure spaces or special education settings. These are other kinds of places for children, which are planned and built for specific needs and capabilities and designed accordingly. In this article, I understand separate leisure spaces as places for certain children. This means recognising that places for children are always intended for specific groups of children, regardless of whether this is intentional or made explicit, and that we need to specify who these children are to understand why places are planned and designed in specific ways as well as to make visible the assumptions and expectations that are part of this process.

Through the concept of children’s places, Rasmussen (Citation2004, 165) illustrates that children not only passively perceive but also actively shape their surroundings; children’s places are ‘places that children relate to, point out and talk about’, i.e. children’s own places. He clarifies that ‘[w]hile children actively use the word “place”, they usually do not talk about “children’s places”’; instead ‘their bodies show and tell where and what these are’ (Rasmussen Citation2004, 165). In this article, places for certain children and children’s places conceptualise the co-existing constructions of separate leisure spaces as (i) planned and designed by adults and (ii) used by children.

How can we study places for certain children and children’s places as they are designed and used in separate leisure spaces? One way is through exploring the planning for, and using of, different action possibilities (cf. Lerstrup and Konijnendijk van den Bosch Citation2017; Lerstrup and Steen Møller Citation2016). This idea comes from Gibson’s (Citation1979) concept of affordances, which he introduced to conceptualise how the environment is perceived by humans. Over time, its meaning has shifted, particularly as it relates to its ontological status (cf. Parchoma Citation2014). Nevertheless, the concept has been used in a range of different fields, including research on children’s environments (e.g. Katsiada and Roufidou Citation2020; Lerstrup and Konijnendijk van den Bosch Citation2017; Lerstrup and Steen Møller Citation2016). In this article, I understand affordances as the action possibilities of the environment, which ‘emerge’ in the encounter between the individual and environment rather than as latent qualities of the environment. I use the concept of action possibilities rather than affordances to accentuate this ontological shift. Like Spencer and Blades (Citation2006, 2), I recognise that action opportunities can be perceived regardless of ‘whether […] those possibilities were originally envisioned by the designers and planners’. In the context of this article, this is particularly important as children may use opportunities that designers have not planned for (cf. Rasmussen Citation2004, 161).

Departing from action possibilities not only facilitates recognising the opportunities that characterise separate leisure spaces as places for certain children and children’s places, however. Rasmussen (Citation2004, 166) suggests that places for children ‘display adults’ ideas about children’. In this sense, action opportunities can help discern the assumptions and understandings informing the design of leisure spaces. Consequently, I emphasise two aspects of action possibilities in my analysis. The first aspect is the possibilities that designers plan for the separate leisure spaces to offer, which I call planned action possibilities. In other words, when places for certain children are designed, it is the planned action possibilities that are considered. The second aspect is the possibilities that children make use of, which I call used action possibilities. Here, I interpret children’s relating to and embodied displays of where and what children’s places are (Rasmussen Citation2004, 165) as children making use of action possibilities. I agree with Lerstrup and Konijnendijk van den Bosch (Citation2017, 50) who departed from the understanding that ‘[a]ctivities and features used were seen as the children’s nonverbal answer to the question about the meaningful action possibilities of the setting’. Thus, departing from the concept of action possibilities facilitates the study of separate leisure spaces from children’s points of views without requiring researcher-led or verbal participation (Tiefenbacher Citation2023). This is consistent with Rasmussen’s (Citation2004, 165) statement that children’s places emerge through their use of their bodies and not their talk. In this sense, the exploration of places for certain children and children’s places through action possibilities is a fruitful combination that helps discern (i) what the environment reveals about designers’ ideas and assumptions about children’s needs and likes, and (ii) how children experience their surroundings.

Method

This study is part of a research projectFootnote1 that explores children with neuropsychiatric disabilities’ right to leisure and focuses on ‘The Panda’. It builds on three years of ethnographic fieldwork, during which I have spent time at The Panda together with children and their families. The study can be understood as part-time fieldwork (Fangen Citation2005, 108), as my visits to the field have not been regular. Instead, two main interests have guided my visits to The Panda. First, I have focused on how children make use of the leisure space. When visiting The Panda together with the children and their families, I have conducted participatory observations of the children’s activities. I have made field notes, video recordings and/or audio recordings of what the children have done and expressed. Instead of introducing research-specific activities, I have gone along with what the children themselves chose to do. This has been my way of exploring the children’s uses of the leisure space without requiring spoken participation, assuming some established means of communication between the researcher and participants and without departing from research-specific adult-devised techniques (cf. Gallacher and Gallagher Citation2008, 503), all of which I found to be problematic during the early stages of the fieldwork. I have elaborated on this, in detail, elsewhere (Tiefenbacher Citation2023).

Like Davies (Citation2007, 83), I recognise the importance of being ‘sensitive to the nature of, and conditions governing […] participation’. This has meant that my role in the encounters with the children has fluctuated, sometimes being more that of observer, sometimes more that of participant (cf. Fangen Citation2005). More specifically, it has not been an end in itself for me to join children’s activities but I have instead been sensitive to children’s invitations to me to join (or not join) their activities. Whereas some children have seemed pleased playing on their own/with each other without my involvement, other children have explicitly asked me to join their activities. I find that it would be unethical for me to decline the children’s invitation and have thus gone along with what the children have been doing.

Second, I have wanted to gain insight into the daily operations of The Panda. I have observed and participated in different activities and events organised by The Panda to understand what happens in a separate leisure space and how it is adapted to its target group. These visits have also been documented through field notes. As a complement to the observations, I and the project PI have conducted 9 interviews with 8 key informants to understand what happened before the premises were built, such as the considerations and ideas that went into planning and designing the space.

For this article, empirical material focusing on the facility’s calm room is used. To discuss the design of the room, I build on observations of the room and one of the supplementary interviews in which the room was discussed in more detail. This helps in understanding why the room was built and what considerations went into designing the room. The analysis of this material has focused on planned action possibilities and how these point to assumptions and concerns about children with neuropsychiatric disabilities’ leisure needs. To discuss how children use the calm room, observations of children’s activities in the room, or with things from the room, are used. Out of 14 recorded occasions, 6 examples from play sessions with 8 children between the ages of 3 and 10 are presented: Elliott, Emanuel, Gabriel, Henry, Kevin, Linus, Stephanie, and Vanessa (pseudonyms). I met Kevin and Henry for one play session and the other children for two to five play sessions respectively. These examples illustrate the diversity in the children’s activities in the room and that these sometimes align with the designers’ planning of the room whereas at other times, children used the room in completely different ways. The analysis of this material has focused on used action possibilities in the room, i.e. how children relate to and make use of the room. This has entailed focusing on which aspects of the room children use and with whom, to understand if and how the calm room becomes a children’s place (Rasmussen Citation2004).

All participants have consented to participating in the study. In accordance with Swedish law, parents consented to their child’s participation before the children were approached. The children consented to participation at each play session and had the opportunity to ask the researcher to stop note-taking, video recording and/or audio recording, an opportunity which some children took up.

Designing a place for children: the adaptations at The Panda

In the planning phases of The Panda, much attention was paid to how to design this place for certain children (Rasmussen Citation2004) to meet children’s perceived needs. This meant that everything from the physical layout of the facility to its sensory impressions was considered and resulted in a multitude of adaptations. Based on how these were talked about in interviews with key informants, as well as my own observations during the fieldwork, I suggest that the types of adaptations can be categorised into three themes. Firstly, there are physical adaptations, including the choice of colours of walls, floors, and toys - which are all in neutral colours – as well as the use of sound-absorbing material throughout the facility. Second, there are adaptations to the social environment, for example that only a restricted number of children are allowed to visit at the same time (3 or 6, depending on the day and time). Finally, there are adaptations to enhance predictability. This means that children should always be able to anticipate what a visit to The Panda will entail. For example, a video is available on The Panda’s website to show visitors what the facility looks like, and special events are announced well in advance on their social media. Taken together, these adaptations point to two important aspects of how the children’s needs are understood: first, as needing environments with minimal, or at the very least fewer, sensory inputs, and second, as needing structure and clarity.

The calm room at The Panda

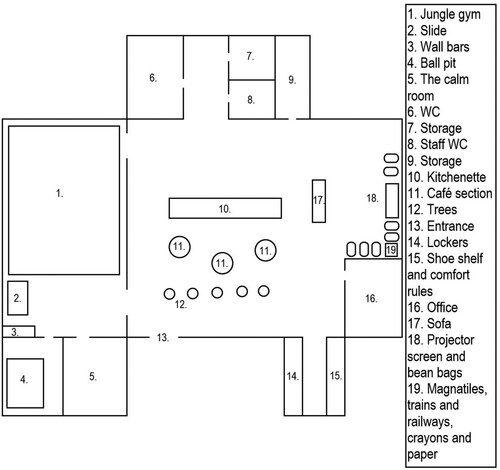

One adaptation that incorporates aspects of all three themes is the calm room. This is a small room located next to the jungle gym and the ball pit rooms (see ), which families can retreat to when children experience sensory overload or when needing to calm down and be on their own. Making space for a calm room - also referred to as a retreat space, escape space or quiet room - is a frequent suggestion in the literature on space adaptations for people on the autism spectrum (e.g. Gaines et al. Citation2018; McAllister and Sloan Citation2016; Nagib and Williams Citation2017) and is commonly described as a room providing minimal sensory input that one can retreat to when experiencing sensory overload. The idea is that this will aid calming down and help avoid ‘negative autism-related behaviours such as aggression and repetitive movements’ (Nagib and Williams Citation2017, 146).

The considerations behind providing a calm room emerged during an interview with Samuel, who was deeply involved in its planning and design. He explained that during the planning phase of The Panda, an expert in the field of neuropsychiatric disabilities had been consulted who estimated that the facility would be visited by children who would be ‘acting out’. To prevent these incidents, and to accommodate their anticipated frequency, the expert advised building two calm rooms in the facility. How many calm rooms should be provided was carefully considered, as building two rooms had to be weighed against other interests such as providing space for the jungle gym and ball pit. Following these concerns, it was ultimately decided that only one calm room should be built. We asked Samuel about the outcome of only providing one calm room and whether there were situations where several families needed the room simultaneously, and if these situations could be handled. Interestingly, Samuel told us that the calm room never really had to be used for the situations initially imagined.

The interview with Samuel demonstrates that the calm room became a central concern in arranging The Panda. This points to an assumption that it was inevitable that (some) children would be ‘acting out’, and that The Panda had to be in a position to be able to mitigate or handle these events. However, the interview also revealed that the room has not come to be used in this way. But how is the room used instead? And how can this be understood in relation to how the room was planned and designed? I continue by analysing the adaptations of the calm room and its planned action possibilities before exploring the many ways in which children have come to use the room. In this way, it is possible to discern the action possibilities that the children use in the room and to compare these to the designers’ planning.

The adaptations in the calm room

While the interview with Samuel provided information about why the calm room was built, less was said in the interviews about the design of the calm room. Here, I want to analyse the adaptations of the room and its planned action possibilities to understand how it was imagined as a space for preventing or handling children ‘acting out’. The analysis departs from the three adaptation themes that I identified in The Panda as a whole, i.e. physical adaptations, adaptations to the social environment and adaptations to enhance predictability.

The physical adaptations in the room serve four functions. First, they minimise auditory impressions in the room. For example, there is sound-absorbing wall art on two of the walls that, together with the rug on the floor, helps reduce the acoustics in the room. The door to the room can also be used to keep out noise. In a grey cloth box on the windowsill are two pairs of child-sized earmuffs that the children can use to further minimise the auditory impressions. A second function of the physical adaptations is to provide minimal visual impressions. This is reflected in the colour choices in the room, such as beige walls and grey furniture. Children and their families can also regulate the light in the room by turning the lamp on and off, making the lamp button an important feature. The third function is to offer space for calming down and resting the body. The two main pieces of furniture in the room are a matching grey sofa and armchair, which offers sitting or lying down. In grey cloth boxes on the windowsill are two weighted blankets that can help calm the body down. Two of the walls in the calm room are also decorated in forest-themed wallpaper which I have been told was chosen for its calming effect. The final function of the physical adaptations is to create an inviting space in the room for calm activities. The sofa, armchair and weighted blankets can be used for lying down and calming down, and in one of the cloth boxes are a selection of books that can also be read as part of the calm activities.

The adaptations to the social environment have two functions. First, the room offers a space for getting away from others, mainly with the help of the door that separates the room from the rest of the facility. This is one of the few doors that children can control and use as they like, the only other two doors being the doors to the toilet and the ball pit room. Second, the room offers children to choose who they wish to be with. Again, the door helps in keeping wanted company in the room and unwanted company outside, but a privacy sign can also be used to indicate that the room is occupied and that, therefore, company is not wanted.

Finally, the adaptations made to enhance predictability in the calm room also have two functions. First, the room has a set look, so that children always ‘recognise’ the room. This is mainly achieved as The Panda’s staff ‘reset’ the room in-between play sessions by returning things to their correct places. Furthermore, whereas other aspects of the facility have been changed during the time I have spent there, the calm room has remained the same. Second, the room has a set function, i.e. to allow space for calming down and to prevent or handle children ‘acting out’. This is reflected by the sign next to the room’s doorway which states that this is the calm room.

Overall, this analysis of the calm room demonstrates that several aspects combined contribute to its planned action possibilities, as summarised in . They point to the idea of children with neuropsychiatric disabilities as needing structure and clarity as well as a place with fewer, or even minimal, sensory impressions, like the rest of The Panda. Moreover, the calm room offers a place for being on one’s own and a place for calming down, which are specific functions of this room. In this way, the planning and design of The Panda is informed by a quite homogenous and specific idea of the needs of children with neuropsychiatric disabilities, despite this being a group of children with diverse needs and capabilities. The calm room is an example of this idea, as it is a place to mitigate and handle one specific type of behaviour, or incident; i.e. children ‘acting out’. This is further demonstrated by the fact that this room – initially rooms – became a central concern in arranging and designing the leisure space.

Table 1. A compilation of the adaptations of the calm room.

But how were the calm room’s offers used by the children if not for handling events of ‘acting out’? Next, I focus on children’s activities in the room to explore what uses children found for the room instead and how these relate to its planned action possibilities.

The making of a children’s place: how children use the calm room

When analysing children’s activities in the calm room, I recognised that it was used in many different ways and for diverse purposes. Sometimes children’s activities in the room corresponded with the designers’ planning and other times, children’s activities in the room clashed with what designers had planned for, i.e. the used action possibilities and the planned action possibilities collided. This provoked reactions from adults present in the facility. What the children’s uses of the room have in common though, is that they demonstrate how the calm room - a place for certain children - can become a children’s place (Rasmussen Citation2004). Here, I analyse six examples of how children used the room. The focus is on how children ‘relate to’ (Rasmussen Citation2004, 165) the room, i.e. the used action possibilities.

One example of how the calm room is used by children, and how this can correspond to the designers’ planning of the room, is from a play session with three-year-old Henry. He was in the café section, having a cinnamon bun and juice (‘fika’) with his parents when he announced that he wanted to go to the calm room.

They fika for a while but then Henry stands up and says that he will rest. His parents tell him that he should fika some more first. He eats some more cinnamon bun before saying again that he is tired. He is lifted from the highchair and walks towards the calm room with his father. The father moves the sign so that it says “occupied” and then they close the door. I remain in the café section with his mother. […] She tells me that it is valuable to have a resting room because Henry needs to be able to go somewhere else when he becomes overwhelmed.

The two conceptions of the room also correspond in an example involving five-year-old Vanessa and three-year-old Stephanie. In this example, things from the calm room have travelled to the adjacent jungle gym room.

Vanessa and Stephanie have walked into the closed ball pit (closed due to Covid-19) and the camera shows the researcher standing in front of the jungle gym, looking into the room with the ball pit. In the background, one can hear the girls’ parents negotiating with Vanessa and Stephanie to get them to leave the room and Vanessa’s and Stephanie’s protests against leaving. The parents suggest that Vanessa and Stephanie can ‘fika’ instead, but Vanessa insists on staying in the ball pit by screaming ‘BALL PIT’. Stephanie exits the room and enters the camera recording as she first sits down on the jungle gym slide. After a few seconds, she leaves the slide and walks out of the jungle gym, where she sees the pink earmuffs from the calm room lying on the floor. She picks these up and tells her parents that Vanessa should have them but gets no response. She then offers them to Vanessa, who has now left the ball pit, but again without response. Stephanie invites the researcher to go to the adjacent room instead and the parents take Vanessa to go and fika.

During a play session with seven-year-old Kevin, the calm room was used as a place for resting. He and I had spent time in the jungle gym when we ended up in the calm room.

Kevin has walked into the calm room to rest. He takes a seat on the sofa, and I sit down in the armchair opposite him. Kevin tells me to sit on the sofa with him, so I do so. Kevin finds a book on the sofa, and I find one too, though he tells me that I can look at his. The book is about animals in the forest and Kevin tells me that he is not so fond of ants and flies and such like, but that he is not afraid of spiders and snakes. Kevin also tells me about pranks, specifically spider pranks, and that if one uses small spiders then it is a prank. For example, if one puts a small spider on the toilet paper or in a book, this is a prank. Then he would not get scared because it is only a prank. He has searched for spider pranks on YouTube. Kevin also tells me about his family in the calm room and asked me if I knew the names of his family members (which I knew). He also told me that he was the youngest in his family and his mother the oldest. Kevin also talked about ventriloquism and that he would/wanted to practice it but that he needed one of those special dolls.

So far, I have presented examples of children’s uses of the calm room which in different ways align with the planned action possibilities of the room, for example the room has been used to handle feeling overwhelmed (Henry) or for ‘social calm’ (Kevin). On the other hand, the examples have also demonstrated important differences from the intended uses, above all insofar as it has been the children who have initiated going to the calm room or using things from the calm room. The three remaining examples that I introduce further digress from the planned action possibilities – even though some of them also involve use of the room’s calming opportunities - with the last two demonstrating the consequences of departing too far from the designers’ ideas of what one should do in the calm room.

During a play session with four-and-a-half-year-old Gabriel and his younger brother, I observed the following activity taking place as I was sitting on a windowsill in the adjacent jungle gym room.

Gabriel, his younger brother, and their mother are in the calm room when Gabriel starts playing with the lamp button. He turns the lamp on and off and comments on this [by telling me that he has turned on or turned off the light]. Then, his mother and brother stay in the calm room with the lights off and Gabriel shuts the door to the room. He tells me that they are sleeping. He alternates between opening the door, turning on the light, and saying ‘dingdong’ (like an alarm clock I think) and then turning the lights off and closing the door. Then he walks toward me and tells me that they are sleeping. Then, he enters the room and closes the door so that all three of them can go to sleep.

Another way of using the calm room that does not align with the planned action opportunities is visible in ten-year-old Elliot’s interaction with the room.

I am sitting on a yoga ball and Elliott is lying on his stomach on another yoga ball. He is trying to balance a stuffed animal in the form of a walrus that he has brought with him to The Panda on a third yoga ball. Elliott’s mother is in the calm room, and she moves from the armchair to the sofa. Then, Elliott turns the light off in the calm room and closes the door and laughs. His mother also seems to have found this funny yet still opened the door again and commented that the door could stay open. Then she sat down on the sofa again and Elliott and I continued sitting/lying on the yoga balls for a bit longer.

The final example of how children use the room is from a play session with seven-year-old Emanuel and four-year-old Linus. This time, it is their activity with me in the calm room that is being disapproved of.

The camera is standing in front of the jungle gym, which is empty. In the background, Linus tells the researcher to follow him into the calm room. Emanuel speaks (though is incomprehensible), and one can hear that he is in the calm room too. The researcher asks what one should do in the calm room and Linus says that he is going to hide. Emanuel and Linus hide under the weighted blankets and one can hear Emanuel repeating ‘hide [gömma sig]’. After a few seconds, the researcher also says that she will hide and shortly after, Linus asks if she has gone and hidden, to which she answers yes. Linus says that he will call for his mother and then yells ‘Mother, can you see us?’ […] The camera shows a staff member approaching and standing outside the calm room. Linus says that he will hide again. One can hear Linus and Emanuel playing around in the background. After about 30 seconds, one can hear the mother and the staff member talk (though they are incomprehensible), and shortly after, the mother comments to Emanuel and Linus that the calm room is for resting, to which the staff member agrees. Linus and his mother are seen leaving the room to go to the bathroom and the researcher is heard in the background asking Emanuel whether he will rest now.

Concluding discussion

If the planning and design of the calm room suggested an understanding of children with neuropsychiatric disabilities as needing a dedicated calm place for managing ‘inevitable’ occurrences of children ‘acting out’, then what do the children’s uses of the room tell us about their needs and preferences? I suggest that they demonstrate that although the room can be used in ways that are similar to what designers had planned, it is also used in other, unintended ways. For example, the way that Kevin, Gabriel, Emanuel and Linus used the room suggests the need and desire for a room in which to play and socialise with others. Furthermore, the children’s uses of the calm room also demonstrate that it has come to accommodate other needs than those that informed the design. The door, for example, not only enables children to be on their own in the room but can also be used to keep their parents away from activities in other rooms (Elliott) or for playing with family (Gabriel). Similarly, the weighted blankets can be used for calming down the body but also as a device for hiding under (Emanuel and Linus). The similarity between all examples is that the use of the room is happening on the children’s initiatives, as it is the children who identify and make use of different offers of (the things from) the calm room. In this way, the room becomes a children’s place through the making of children’s activities (Rasmussen Citation2004) when they attribute their own meaning to the room and use it for their purposes.

Some of the ways that children used the room are particularly interesting, as they reveal tensions between the calm room as a place for certain children (the designers’ plans for the room) and the room as a children’s place (children’s uses of the room). For example, when Elliott used the room to ‘lock away’ his mother, rather than close himself in, he seems to have transgressed what is allowed, as his mother told him to leave the door open. Similarly, when Emanuel, Linus and I hid under the weighted blankets in the room, using them for play rather than calming down, these tensions were made even more visible. The tensions, I suggest, emerge as assumptions and ideas about children’s needs that have informed the design of the room conflict with what children need or want when visiting The Panda. For example, Elliot’s ‘locking away’ of his mother suggests that rather than having to be on his own in the calm room – as the room is planned for – he wants to be on his own elsewhere in the facility. Similarly, when Kevin uses the room for ‘social calm’, he demonstrates that he wants a place for socialising with others whilst resting his body. Altogether, this points to the importance of not having too rigid ideas about the needs of children with neuropsychiatric disabilities when planning and designing places for them. One way of avoiding this could be accomplished by finding ways to include the children in the design process, as it is for them that the spaces are made. This would ensure that the diversity of needs and desires are considered and that it is children’s actual needs rather than those assumed or imagined by adult designers that are guiding the process.

The focus of this article has been the design and organisation of separate leisure spaces and, more specifically, the calm room in the separate leisure space ‘The Panda’. The implications of the study extend beyond this specific leisure space, however. First, the study points to the importance of recognising children with disabilities as users of different public and private spaces and of considering their needs and desires in the planning and design of these. This is a prerequisite for creating sustainable cities and communities in line with Goal 11 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and for realising the children’s rights to, among other things, equal access to physical environments and public facilities and services according to the CRPD (United Nations Citation2008, Article 9). Second, we need to find ways to involve children with disabilities in the planning and design processes, so that these are informed by their actual needs and preferences and not only those assumed or imagined by adult designers. This means that children with disabilities should not only be considered in planning and design processes but also consulted. The work of child studies and disability studies scholars is a great starting point for informing those processes (cf. Clark Citation2017; Maconochie Citation2018; Tiefenbacher Citation2023). Finally, the study emphasises the importance of not homogenising children with disabilities but instead recognising the diversity of their needs, desires and capabilities in the planning and design of public and private spaces. In this sense, the current study helps advance more accessible and inclusive spaces for children with disabilities and, accordingly, contributes to the field of disabled children’s geographies (cf. Ryan Citation2005).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority. Dnr 2019-05113.

References

- Avramović, Maša, and Nevenka Žegarac. 2016. “‘Me at the Centre’: Perspectives of Children with Disabilities on Community-Based Services in Serbia.” Children's Geographies 14 (5): 541–557. doi:10.1080/14733285.2015.1136735.

- Black, Rosemary, and Janice Ollerton. 2022. “Playspace Users’ Experience of a Socially Inclusive Playspace: The Case Study of Livvi’s Place, Port Macquarie, New South Wales, Australia.” World Leisure Journal 64 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1080/16078055.2021.1894230.

- Botha, Monique, Jacqueline Hanlon, and Gemma Louise Williams. 2021. “Does Language Matter? Identity-First Versus Person-First Language Use in Autism Research: A Response to Vivanti.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 53 (January): 870–878. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04858-w.

- Bury, Simon, Rachel Jellett, Jennifer Spoor, and Darren Hedley. 2020. ““It Defines Who I Am” or “It’s Something I Have”: What Language Do [Autistic] Australian Adults [on the Autism Spectrum] Prefer?” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 53: 677–687. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04425-3.

- Clark, Alison. 2017. Listening to Young Children, Expanded Third Edition. 3rd ed. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Curran, Tillie, and Katherine Runswick-Cole. 2014. “Disabled Children’s Childhood Studies: A Distinct Approach?” Disability & Society 29 (10): 1617–1630. doi:10.1080/09687599.2014.966187.

- Davies, Charlotte Aull. 2007. Reflexive Ethnography. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Fangen, Katrine. 2005. Deltagande Observation [Participatory Observation]. Malmö: Liber ekonomi.

- Fernandes, Kim. 2022. “Inclusive Education in Practice: Disability, ‘Special Needs’ and the (Re)Production of Normativity in Indian Childhoods.” Children's Geographies 20 (6): 818–831. doi:10.1080/14733285.2022.2124845.

- Gaines, Kristi, Angela Bourne, Michelle Pearson, and Mesha Kleibrink. 2018. Designing for Autism Spectrum Disorders. London: Routledge.

- Gallacher, Lesley-Anne, and Michael Gallagher. 2008. “Methodological Immaturity in Childhood Research?” Childhood 15 (4): 499–516. doi:10.1177/0907568208091672.

- Gibson, James. 1979. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Psychology Press.

- Goodwin, Donna, and Kerri Staples. 2005. “The Meaning of Summer Camp Experiences to Youths with Disabilities.” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 22 (2): 160–178. doi:10.1123/apaq.22.2.160.

- Hodge, Nick, and Katherine Runswick-Cole. 2013. “‘They Never Pass me the Ball’: Exposing Ableism Through the Leisure Experiences of Disabled Children, Young People and Their Families.” Children's Geographies 11 (3): 311–325. doi:10.1080/14733285.2013.812275.

- Holloway, Sarah. 2014. “Changing Children’s Geographies.” Children's Geographies 12 (4): 377–392. doi:10.1080/14733285.2014.930414.

- Holt, Louise. 2004. “Children with Mind–Body Differences: Performing Disability in Primary School Classrooms.” Children's Geographies 2 (2): 219–236. doi:10.1080/14733280410001720520.

- Holt, Louise. 2007. “Children’s Sociospatial (Re)Production of Disability Within Primary School Playgrounds.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 25 (5): 783–802. doi:10.1068/d73j.

- Jeanes, Ruth, and Jonathan Magee. 2012. “‘Can we Play on the Swings and Roundabouts?’: Creating Inclusive Play Spaces for Disabled Young People and Their Families.” Leisure Studies 31 (2): 193–210. doi:10.1080/02614367.2011.589864.

- Katsiada, Eleni, and Irini Roufidou. 2020. “Young Children’s use of Their Setting’s Internal Floor Space Affordances: Evidence from an Ethnographic Case Study.” Early Child Development and Care 190 (10): 1512–1524. doi:10.1080/03004430.2018.1539843.

- Lerstrup, Inger, and Cecil Konijnendijk van den Bosch. 2017. “Affordances of Outdoor Settings for Children in Preschool: Revisiting Heft’s Functional Taxonomy.” Landscape Research 42 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1080/01426397.2016.1252039.

- Lerstrup, Inger, and Maja Steen Møller. 2016. “Affordances of Ditches for Preschool Children.” Children, Youth and Environments 26 (2): 43–60. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.26.2.0043.

- Maconochie, Heloise. 2018. “Making Space for the Embodied Participation of Young Disabled Children in a Children’s Centre in England.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Disabled Children’s Childhood Studies, edited by Katherine Runswick-Cole, Tillie Curran, and Kirsty Liddiard, 125–139. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McAllister, Keith, and Sean Sloan. 2016. “Designed by the Pupils, for the Pupils: An Autism-Friendly School.” British Journal of Special Education 43 (4): 330–357. doi:10.1111/1467-8578.12160.

- Nagib, Wasan, and Allison Williams. 2017. “Toward an Autism-Friendly Home Environment.” Housing Studies 32 (2): 140–167. doi:10.1080/02673037.2016.1181719.

- Parchoma, Gale. 2014. “The Contested Ontology of Affordances: Implications for Researching Technological Affordances for Collaborative Knowledge Production.” Computers in Human Behavior 37 (Aug.): 360–368. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.028.

- Place, Kimberly, and Samuel Hodge. 2001. “Social Inclusion of Students with Physical Disabilities in General Physical Education: A Behavioral Analysis.” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 18 (4): 389–404. doi:10.1123/apaq.18.4.389.

- Pyer, Michelle, John Horton, Faith Tucker, Sara Ryan, and Peter Kraftl. 2010. “Children, Young People and ‘Disability’: Challenging Children's Geographies?” Children's Geographies 8 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/14733280903500059.

- Rasmussen, Kim. 2004. “Places for Children – Children’s Places.” Childhood 11 (2): 155–173. doi:10.1177/0907568204043053.

- Runswick-Cole, Katherine. 2014. “‘Us’ and ‘Them’: The Limits and Possibilities of a ‘Politics of Neurodiversity’ in Neoliberal Times.” Disability & Society 29 (7): 1117–1129. doi:10.1080/09687599.2014.910107.

- Ryan, Sara. 2005. “‘People Don't do odd, do They?’ Mothers Making Sense of the Reactions of Others Towards Their Learning Disabled Children in Public Places.” Children's Geographies 3 (3): 291–305. doi:10.1080/14733280500352920.

- Shakes, Pieta, and Andrew Cashin. 2020. “An Analysis of Twitter Discourse Regarding Identifying Language for People on the Autism Spectrum.” Issues in Mental Health Nursing 41 (3): 221–228. doi:10.1080/01612840.2019.1648617.

- Smart, Eric, Brydne Edwards, Shauna Kingsnorth, Sarah Sheffe, C. J. Curran, Madhu Pinto, Shannon Crossman, and Gillian King. 2018. “Creating an Inclusive Leisure Space: Strategies Used to Engage Children with and Without Disabilities in the Arts-Mediated Program Spiral Garden.” Disability and Rehabilitation 40 (2): 199–207. doi:10.1080/09638288.2016.1250122.

- Spencer, Christopher, and Mark Blades. 2006. “An Introduction.” In Children and Their Environments, edited by Christopher Spencer, and Mark Blades, 1–10. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stephens, Lindsay, Karen Spalding, Henna Aslam, Helen Scott, Sue Ruddick, Nancy Young, and Patricia McKeever. 2017. “Inaccessible Childhoods: Evaluating Accessibility in Homes, Schools and Neighbourhoods with Disabled Children.” Children's Geographies 15 (5): 583–599. doi:10.1080/14733285.2017.1295133.

- The Swedish Agency for Participation. 2020. Aktiv fritid: Redovisning av ett regeringsuppdrag om att kartlägga lokala och regionala satsningar samt tillgången till fritidshjälpmedel [Active leisure: Reporting a governmental commission about mapping local and regional investments and access to leisure aids]. https://www.mfd.se/contentassets/28aeb8c0d4de48999b8b9cc15cae97c8/2020-6-aktiv-fritid.pdf.

- Thompson, David, and Mahmoud Emira. 2011. “‘They say Every Child Matters, but They Don't’: An Investigation Into Parental and Carer Perceptions of Access to Leisure Facilities and Respite Care for Children and Young People with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or Attention Deficit, Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).” Disability & Society 26 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1080/09687599.2011.529667.

- Tiefenbacher, Rebecka. 2023. “Finding Methods for the Inclusion of all Children: Advancing Participatory Research with Children with Disabilities.” Children & Society 37 (3): 771–785. doi:10.1111/chso.12628.

- United Nations. 2008. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.