ABSTRACT

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, diverse changes have been made in schools. The decision was made for students to be back in school online, and synchronous bi-directional online classes were launched as a means of ‘blended learning’. Against this background, we aim to explore how synchronous bi-directional online classroom space is understood and materialised through a lens of socio-material assemblage. This article builds on existing literature on the potential of liminal space, which encourages a focus on the limits of the space and the simultaneous possibility of students’ agency. Online ethnography was conducted to analyse the dynamics of spatiality in an online classroom. Participant observation was conducted in online classes in one 6th grade (elementary school) class in Seoul, South Korea, followed by semi-structured interviews with the teacher and students. We explore themes of students being controlled and (simultaneously) exercising their agency, thus opening up understanding of the agency of children as active actors who construct the space.

Introduction

Since 2019, schools around the world have seen abrupt and diverse changes due to the spread of COVID-19. In the South Korean context, the start date of the new semester was delayed due to the pandemic from March to April 2020. Once the semester started, online classes were mainly delivered through pre-recorded lectures involving content-based learning materials. Concerns over a decreased level of academic achievement were raised, however, and synchronous bi-directional (SBD) online classes – where students and teachers interact with each other – were therefore implemented as an alternative in the second semester of 2020. In 2021, most schools decided to deliver both SBD online classes and traditional offline classes in schools. The Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education (Ko Citation2020) declared that ‘genuine blended learning’ had been launched, integrating the two types of classroom. Blended learning was implemented in schools differently depending on the population and the school environment. Schools with dense populations, in cities, used more SBD online classes in 2021, except for 1st and 2nd graders in elementary school. For instance, in some schools, 3rd and 4th graders came into school for traditional classes 3 days a week, and logged on for SBD online classes 2 days a week. As the number of new COVID-19 cases declined from 2022, and vaccination had begun in 2021, SBD online classes were no longer used in schools. From March 2022, most students attended school on an everyday basis, while students who had COVID-19 could log on to SBD online classes to participate.

Although students experienced rapidly changing policies during the pandemic, they were excluded from decisions about whether they would go to school or attend classes at home. The ways in which school was transformed for two years were determined by central government, without consideration of either the regional situation or the accessibility of the online environment. For instance, first – and second-grade students in elementary school had to watch several videos of activities each day during the first year of the pandemic, instead of doing in-person activities with their peers. Whilst there is much that might be discussed about children’s experiences of school during the pandemic, it is clear that students were considered to be passive recipients who needed to adjust their lives to changing situations.

Against this backdrop, we aimed to conduct a study focusing on students’ agency within changes in schools during COVID-19, by undertaking an ethnography in SBD online classes – specifically, the year 6 social studies class of a South Korean elementary school. The decision in this study to explore the students’ limited agency yet (nevertheless) active exercise of agency was guided by the potential of liminal spaces framework (Hadfield-Hill and Christensen Citation2021; Matthews Citation2003). This framework engages the lived experience of in-betweenness, enabling understanding of the space as a site of both surveillance and resistance. It draws attention to the dynamic, unfolding, and often contradictory status of children and young people’s agency (Wood Citation2012). Within the framework, the online classroom site can be examined as a space of in-betweenness, where both adult control and youth agency are enacted simultaneously. The framework expands the potential to focus on students’ embodied responses, which are a key part of strategies of resistance and mutual surveillance. In the following section, we further explain how the space may be understood, by navigating the gaps in the literature on the changes made in classrooms due to COVID-19.

Socio-material assemblage of the online classroom

Studies of the online classroom after COVID-19 discussed the opportunities (Baek Citation2020; Oh Citation2021) and pitfalls (Baek and Jeong Citation2021; Chae Citation2020; Lee, Min, and Park Citation2020) of online classes, and suggested mitigating strategies (Kim Citation2021; Seo Citation2021). On the one hand, the implementation of SBD online classes in schools was considered a panacea for ‘future education’ (Baek Citation2020, 5). Potential positive changes with new ways of learning facilitated by online platforms were discussed (Oh Citation2021). On the other hand, negative changes in educational outcomes due to the introduction of online classes were noted, including the impact of online learning on students’ development of academic knowledge (Lee, Min, and Park Citation2020) and competency in relationship-building and communication (Baek and Jeong Citation2021). Such changes were attributed to the lack of ‘sharing the common sense of experiencing the same space and time’, because students no longer had physical contact with one another (Chae Citation2020, 121). With a view to mitigating strategies, an increasing number of studies were conducted to discuss technical developments (Kim Citation2021; Seo Citation2021) and effective teaching methods (Lee and Park Citation2022).

We identified limitations in the burgeoning literature around online class(rooms) upon the outbreak of COVID-19. First, studies investigating perceptions and evaluations of online classes have primarily involved adult perspectives (such as those of parents, teachers, and head teachers), excluding children and young people’s views and experiences of online class(rooms). In a few exceptional cases, studies included students’ views (e.g. Kim Citation2021; Kim and Park Citation2022), but the scope of inquiry was narrowly focused on the impact of online learning on academic achievement. Second, studies often viewed available technology in the online space as an object: a passive entity that is merely the platform on which the online class is delivered (e.g. Oh Citation2021; Seo Citation2021). In such a perspective, the non-human object is perceived to be utilised by the human actors, rather than actively constructing complex practice in the online space. Yet the online classroom platform is part of entanglements and assemblages among human and non-human things, where children’s agency is enacted (Baroutsis Citation2020). Furthermore, the insidious managerialism of EdTech shapes and constricts the engagement of student-teacher and curriculum (Moore, Jayme, and Black Citation2021). Third, distinguishing the online class(room) from the traditional offline class(room) has the effect of demarcating the different learning outcomes generated by the different spatialities (e.g. Baek Citation2020; Oh Citation2021). We suggest, however, that demarcating the online and offline class(room) does not capture the mutually related time-spaces of these classrooms, through which power relations persist. These limitations in the literature mainly reflect education policies shaped by neoliberal aims that define children as future adults, relating education to the economic process (Garlen et al. Citation2022).

Given these gaps in the literature, we aimed to understand how students navigate their agency in the potential liminal spaces of online class. Agency refers to actions that can be transformed to subvert dominant authority: it is entangled intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socio-political ways (Garlen et al. Citation2022). Agency is mutually constituted by discourses and relationships among both human and non-human material entities (Gallagher Citation2019). We identified such relationships by using a socio-material assemblage lens to capture the complex relations among: (1) human actors and (2) human actors and non-human material. This article is situated within larger theoretical debates about foregrounding young people as subjects rather than objects of education (Holloway, Brown, and Pimlott-Wilson Citation2011), the constitutive role of material objects in space (Kalthoff and Roehl Citation2011), and the conflation of online and offline spaces (Bork-Hüffer, Mahlknecht, and Kaufmann Citation2021).

Socio-material assemblage (Kalthoff and Roehl Citation2011) explains an entanglement between human actors and nonhuman material which helps further our understanding of the spatiality of online classrooms. Opposing the humanist perspective that often downplays the contribution of material objects to education and views them as neutral means to an end, Roehl (Citation2012) suggests that material objects both shape and are shaped by human practice, closely interwoven with human actors in socio-material practice. The materiality is considered to have spatialising power, which actively constructs social spaces by mediating between human beings, rather than being passive mechanical equipment utilised by human actors (McGregor Citation2004). This framework recognises, on the one hand, the social construction of material objects through human interaction and discourse – and, on the other, the constitution of classroom discourse through the network created by material objects (Kalthoff and Roehl Citation2011). The roles of the objects in classrooms are analysed, followed by attention to the emergence of meanings assigned to the objects by the human actors, revealing the practices and daily routines around the role of the material object. Social relations between human beings, objects, and the world are also considered: at this stage the relational background (Massey Citation1994) of which human actors and objects are part is also analysed. We understand space to be constructed in terms of the dynamics, relations, and networks of the space itself, but also connected to power relations operating beyond the space. The socio-material assemblage framework enables the expansion of questions on hierarchy and power in education, by illuminating the material enactment of these inequalities in the classroom (Roehl Citation2012).

Methods

This study was conducted using an ethnographic approach in an online environment. Ethnography is often suggested as a method suitable for studying materiality in educational spaces, since it offers methodological opportunities to capture implied meanings of materials (Kalthoff and Roehl Citation2011), as well as power relations in educational settings (Webster and da Silva Citation2013). As part of this ethnography, we conducted participant observation in online classes and in-depth interviews with the teacher and students. Participant observation was conducted in SBD online classes for social studies in one 6th grade classroom of HANEUL (anonymised) elementary school in Seoul. The group was chosen because elementary schools quickly adopted SBD online classes as a mitigating measure during the COVID-19 outbreak, and the sixth grade was the first to implement the change. During the period in which data were collected, HANEUL elementary school students were having online classes three times a week and offline classes twice a week. This enabled participants to reflect upon the schooling experience in three different spatio-temporal contexts: the offline classroom before COVID-19, the online classroom, and the offline classroom since COVID-19.

The online social studies class lasted for 30 min on the Zoom platform, and the researcher participated in the class once a week for five weeks. The class lasted 30 min because the traditional 40-minute class schedule was shortened due to COVID-19. Behaviours, comments, reactions, and non-verbal expressions of participants (who had provided written consent for participation into observation) were written down in fieldnotes. Scenes that were ‘not seen’ over the screen (due to participants turning off their camera) and sounds that were ‘unheard’ over the headphones (due to the mute function being used during class) were also noted. This is because these ‘unseen’ and ‘inaudible’ actions were considered to be another form of active participation, in making use of the materiality of the online classroom space. Vignettes of class activities involving diverse materials were written down, and special attention was paid to how individual participants enacted relations with others and with materials in the online classroom space.

On completing participant observation, online in-depth interviews with individual participants were conducted, lasting between an hour and an hour and a half. To facilitate a child-friendly interview environment, we started off by drawing pictures with the participants that enabled comparison between online classes and traditional offline classes. Participants reflected on their previous experiences and shared specific episodes that had attracted their interest, relating to their drawings.

We conducted thematic analysis to understand the significance of the overall data set by identifying themes through careful reading and re-reading of data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). We first identified relational and material dimensions of the online classroom as codes through initial deductive coding and then attempted to elaborate interpretations of the codes by connecting the codes and identifying categories and themes through inductive coding (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2006).

We sought both verbal and written consent from the teacher and the principal of the school to participate in and observe online classes. We then sought written consent from both the students and their parents or guardians. A separate, child-friendly information sheet for student participants was created, involving pictures explaining what would happen during data collection and how the data would be used in research. We decided, in consultation with the participants that the researcher’s camera would stay turned off, but we notified participants in advance of the researcher’s presence in online classes, to avoid the ethical problem of lurking (Angelone Citation2019). 11 students (all aged 11–12; 5 female, 6 male) and a teacher provided written consent to participate in the participant observation. 8 students (5 female, 3 male) and a teacher provided written consent to participate in the interviews, with one student opting out of the study before the interview (hence not included). The students who did not provide written consent were aware that the research was being conducted in their online classroom, but no information regarding them was recorded in fieldnotes. Participants’ names have been replaced with pseudonyms. Ethics approval was obtained from the Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy before collecting data.

Participants were all in the same online space and were attending the same class when participant observation was conducted, but they all seemed to be participating from different backgrounds and contexts – showing how an online classroom is constructed with each participant bringing their own contexts of time and space (Lee Citation2021). A detailed description of the participants is given in the table below ().

Table 1. Description of participants

In the following section, we move on to analysing how participants’ diverse real-world contexts construct their online classroom spatialities, by engaging in the complex interplay of human and non-human actors. We present a vignette of teacher and students conducting an activity in the online social science class and analyse the meaning of the ‘messiness’ of the online classroom we observed.

The ‘Messiness’ of spatiality in the online classroom

Teacher: Anyone who has finished their work?

Nakyung: I’ve finished it!

Teacher: Could you show it to me Nakyung? Show it to me on screen.

(Nakyung holds up her workbook on screen)

Nakyung: May I leave?

Teacher: Yes, you may. Yes, let’s have a look at Minyoung’s work.

Jeongwoon: Teacher! What should I do?

Teacher: Hold on for a second Jeongwoon. Minyoung, which country did you work on?

Minyoung: The UK.

Teacher: What’s going on Jeongwoon?

Jeongwoon: I haven’t decided the country yet.

Teacher: Still haven’t decided it?

Yuri: What should we write in ‘investigation methods?’

Teacher: Internet.

Minsoo: Teacher, I am writing it on a separate sheet of paper because I haven’t brought the textbook with me.

Teacher: Okay that’s good. We will be talking about this again tomorrow during class, so please keep the paper Minsoo.

Yuri: I don’t know what I need to write for ‘content of investigation.’

Jeongwoon: Teacher, I forgot how to access the data. Can you please show it to me again?

Teacher: Okay, I will show it to you. Jaeseong, I’ve checked yours.

Yuri: I don’t know what I need to write for ‘content of investigation.’

Teacher: You can have a look at the ‘items of exchange,’ and when you write the ‘content of investigation’, write a list of ‘import items’ from the highest to the lowest.

Jeongwoon: Ah! I got it.

Yuri: What do you mean?

(All the sounds overlap)

Jeongwoon: Teacher!

Yuri: I don’t know what to write.

Jeongwoon: I found it!!! What? Teacher! Teacher, that export thing. What … ? Based on countries? Ah!! I went into the wrong website.

Soyeon: Teacher

Teacher: Yes, Soyeon, what did you say?

Soyeon: The ‘content of investigation … ’ What should I write?

At first glance, we were struck by the messiness of overlapping noises and voices from the fieldwork. This resulted from the screens constantly switching back and forth between presentation slides, textbooks, and the teacher’s shared screen with all the students’ faces on it. ‘(Name), I want to see your face, not your ceiling’, the teacher often said. She had to remind the students to turn their cameras on, under pressure to keep track of everyone’s progress in class. However, two thirds of the students’ cameras were off in this class, while the ones that were on displayed various backgrounds. While the teacher was leading the class and the students were writing down notes, answering the quiz, and filling in the blanks, the sounds of students coughing, moving chairs around, and dropping pens all overlapped, producing a range of noise. Focusing on these noises and changing screens, we at first conducted participant observation from the teacher’s perspective. During the interviews, we were able to re-read the ‘messy’ online classroom by considering students’ perspectives. Directing attention toward how children’s agency is entangled within the assemblage of bodies, objects, and forces in the classroom provided an opportunity to understand how their agency was enacted in this setting (Garlen et al. Citation2022).

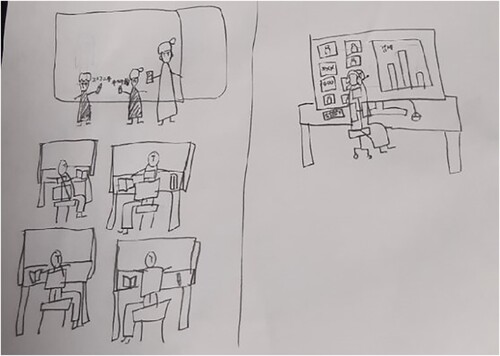

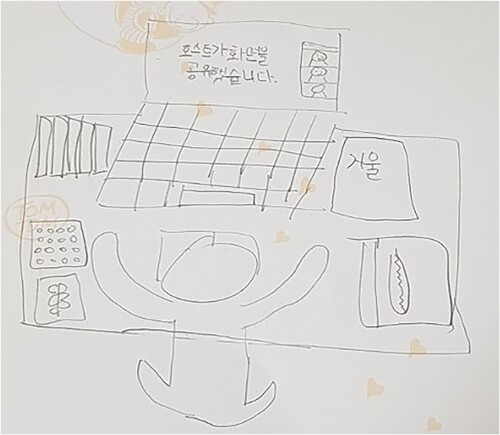

By asking participants during the interviews to draw pictures to illustrate how they engaged in online class, we were able to notice the different settings in which each participant entered the online classroom. The pictures below show how the time-space of SBD online classes was constituted from separate time-spaces – even though, on the surface, it looked as though participants took part in the same class ().

Figure 1. Picture of teacher’s desk in school, set up to deliver online class. Note: As illustrated in-text, the picture shows how the teacher engages in online classroom. The teacher enters the online classroom in the traditional offline school classroom, using four different devices to deliver, share, and monitor class.

The picture of the teacher’s desk illustrates where and how the teacher engaged in the online class, simultaneously managing different tasks. The main screen was used to share presentation slides or the webpages she referred to during class, while the second screen was used to monitor students’ responses, reactions, and attendance in the classroom. The teacher also kept the third screen on, the tablet, to look at her lecture notes. The fourth screen was her own mobile phone, through which she accessed the classroom from a student’s perspective to monitor whether her teaching was well-delivered in the online environment without any technical issues ( and ).

Figure 2. Eunsoo’s picture of offline/online classrooms. Note: In the picture, Eunsoo demonstrates on the right side his experience of taking online social science class, learning economics graph. On the left side, it shows what he imagines of an offline class, where a teacher is instructing in front, two students are solving maths equations on the board, and other students are sitting in their own desks facing the board.

Figure 3. Yoohyun's picture of the online classroom. Note: In the picture, Yoohyun demonstrates the environment in which she engages in online classes. As illustrated in-text, she shows what she has on her desk, including a mirror, a pen, a notebook, nail polish set, and books.

The pictures of online and offline classrooms that the students drew illustrate quite different scenes and perspectives. Eunsoo’s picture (on the right) shows how he attended online class from home using a separate big screen, headphones, and a speaker, which enabled him to view both the teacher’s slides and his peers’ faces simultaneously. Yoohyun attended online classes in a different setting, using a laptop and looking at a smaller screen. On her desk, she had a mirror and a nail polish set. The three different pictures, from the students and the teacher, indicate how every participant in the online classroom engaged in the ‘identical’ online space from different individual settings (Lee Citation2021, 124).

By discussing the pictures, we realised that although the students’ experiences were various, the screen the teacher chose to show readily erases their voices and different perspectives. The teacher, who was the Zoom account ‘owner’, had a default set of permissions, enabling users’ access and choosing which screen to share. On the other hand, students became ‘members’ who did not have any administrative privileges. They could only adjust their own settings, turning their video or audio on or off. The account roles, already set by the platform, restricted the students’ ability to understand what was happening beyond others’ screens. By realising how the general settings rule and regulate the agency of students, we came to understand how we viewed the classroom space from the adults’ perspective.

Analysing different spatialities of the classroom, we suggest seeing the ‘messy’ online classroom as a potential liminal space, which enables an active role for students who open upspaces between being controlled and exercising agency. In the following sections, we first discuss how students’ classroom practices are controlled by various power relations. We then move on to discuss how students actively navigate their agency within limited spatiality.

Being controlled: ‘I am keeping an eye on them’

School spaces are never neutral but are constructed by the students and teachers who inhabit them. Students construct their adaptive ways of learning and produce their own space (Hedman and Mannish Citation2022). However, spaces also influence how students act within different spatial arrangements (Variyan and Reimer Citation2021), which limits students’ exercise of agency in the classroom. Specific spatial arrangements create a power system, embedded with discipline, control, and the regulation of bodies (Barker, Alldred, Watts, and Dodman Citation2010). In this section we discuss how students’ classroom practices are limited and how the space itself is in control, through regulation in three areas: (1) active communication, (2) mutual learning, and (3) students’ participation. We analyse the interlocking power relations that guide the interpretation of different potential roles that material objects play in an online classroom.

First, the students noted that their active communication is limited by the teacher-student power relation in schools. In contrast to the anticipated outcome of implementing SBD online classes, what we observed during participant observation was a lack of interaction or active discussion between students. The teacher’s excerpt below provides a potential reason:

Hayoon (Teacher): They [the students] keep making jokes if the chat function is open to everyone. We once invited a speaker and the head teacher was also there. They were playing with each other in the chat room so the head teacher had to stop the lecture and tell them to stop chatting. He said the teachers are keeping an eye on them. But they went on. So we had to carry on with the chat rooms closed. After that, they can only talk to me in chat rooms during classes. I change the options so that everyone can chat to each other only when necessary.

Jeongwoon: When I imagine speaking in a Zoom classroom, [there are] many students … . For example, I may want to speak to one specific friend, but everyone gets to hear what I say. On Zoom, I mean. So I have to stop speaking.

Nakyung: So what I’m trying to say is maybe it’s good for the teacher because we get to concentrate more on what she’s saying, but I cannot speak with my friends about relevant stuff. I only get to speak during class and it sometimes makes it a bit more boring.

Second, the students’ and teacher’s accounts illustrate different uses of the material object (the shared screen) in an online classroom, which cross the boundaries between mutual learning and surveillance:

Yoohyun: When I was in school, and I was lost or spaced out, I would take a look at my friends’ answers around me. But when I am on Zoom, I don’t know what to do. I just sit in panic.

Nakyung: I take a look at what other people wrote. Because, I am curious about other people’s answers when the teacher says ‘show your answers on the screen so I can see it’.

In Yoohun’s and Nakyung’s accounts, the changes in possibility of classroom practice seemed to be attributed to the unique character of material objects in an online space. The experiences of the two students are differentiated, as they are the social agents constructing their own meanings during class (Thomson Citation2005). Moreover, the teacher’s account of how she made use of the material object (the shared screen) in the online classroom suggests a different understanding:

Hayoon: I do so because they [the students] can focus on class better when they see themselves. I know they only get to see my face on the screen, so they don’t recognise that I am looking at them in a gallery format. So, I share the screen that I am looking at [in a gallery format including everyone’s faces] on purpose to make them realise that I am keeping an eye on them. I share the screen and say ‘Turn on your screen, guys!’. Then everyone can see who has turned off their camera. I do this often. Then the students check their faces and try to watch the screen more than before.

Third, we present how students’ participation was limited by their teacher not being able to decide which classes to teach online or offline, due to power relations among schoolteachers:

Hayoon (Teacher): I mean I really wanted to have physical education classes. But the head teacher of our grade didn’t really like it. What sports class could I plan in content-based online classes? So I just had to upload video clips for them to watch. Stretching, yoga and stuff like that. Who would watch it to be honest? But I just uploaded it anyway.

Researcher: Yeah. The students seemed to be sad to have missed the P.E. classes.

Hayoon: I know. Because sixth graders really love P.E. classes. But what would the youngest teacher and a newcomer do, when the head teacher says so … .

In this section, we have discussed the limitation of participants’ agency in the online classroom space by different power relations under three themes. In the next section, we discuss students’ active exercise of their agency, navigating their engagement in the online space.

Navigating students’ agency: ‘I don’t want to show my face’

Even if the structure of the SBD online classes may seem the same as that of life, the conditions of the class are not necessarily the same (Jo, Yun, and Lee Citation2006). This is because every actor practises and interprets the same conditions differently. The actors actively make use of the conditions to change their surroundings. Likewise, in the classroom, the same conditions turn out to have different results depending on the participants, as the classroom space is differently perceived and experienced by individual actors.

As the previous section addressed, the interlinked power of materiality and relationality limits students’ agency in different ways. However, even in adult-centred and controlled schools, children do not passively comply with adults’ efforts (Barker at al. 2010). Rather, they apply strategies to resist the power structure, as possibilities always exist for mundane resistance in space (Soja Citation1985). In this section, we discuss how the students actively navigated their agency by utilising the materiality of the online classroom in three ways: (1) acute self-monitoring; (2) determination of self-display; and (3) active engagement in questioning.

First, students constructed the ability for themselves and peers to communicate in an orderly manner in class by actively utilising the material functions of the online classroom. Soyeon’s excerpt below is an example of how individual actors in the online classroom actively discipline themselves to self-monitor how their sounds are delivered to the other participants via the online medium:

Researcher: Is there any change you would make from the class [with various noises]?

Soyeon: There’s nothing I want from friend but I would love to have a functional alarm from Zoom when the sound of my background [noise] is sent instead of my voice. Maybe something like an alarm with a message saying, ‘Noise is detected.’

Researcher: You mean, in case you forgot to mute yourself?

Soyeon: Yes.

On the other hand, we frequently observed students’ acts of acute self-monitoring. The students paid attention to the changing situation in the classroom, and strictly committed themselves not to distract others. For example, Soyeon, as shown above, kept herself aware of her microphone status. The students became the actors who constituted the space while making different choices in the online classroom (Stratford, Stewart, and te Riele Citation2022). By constructing new rules among themselves as autonomous actors, students actively used the material object and transformed the potential shortcomings of the materiality.

Second, students made active use of the screen in the online classroom to determine the extent of self-display. The screen shown in the online classroom reflected the person’s body, face, and physical surroundings, delivered through the camera of a smartphone, tablet, or laptop. The materiality blurred the boundary between private and public life, and in some cases explicitly depicted where the participants were. The participants recognised that their background (i.e. their home) could be displayed on screen unintentionally due to the materiality of the screen in an online classroom, and exercised self-surveillance in turn, by constantly monitoring how they were displayed on screen:

Nakyung: I prefer not to show my room because I am a bit embarrassed about not being organised.

Taeeun: In the morning, I don’t want to show my face, and I think I got used to my face with a mask on. (Laughs) I don’t show my face on screen. (With the mask on,) I can only see half the face, and everything looks different.

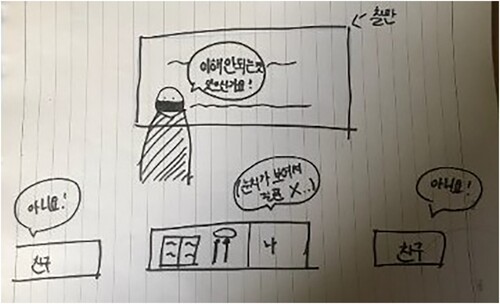

Lastly, students created a liminal space to freely raise questions during class by making use of the materiality of the online classroom. Students actively accepted, modified, and resisted specific subjective positions (Pike Citation2008), indicating the entangled agency of students:

Taeeun: When I am behind, I don’t feel like raising my hand in offline classes to ask my teacher. But in online class, I ask her because I can talk to her privately.

Researcher: Why do you feel you can’t raise your hand in offline classes?

Taeeun: Because people look at me. Hmm. (smiling) I feel very pressured.

Researcher: What do you mean, that you feel pressured by others looking at you?

Taeeun: I mean, it’s because maybe what I asked is not an important thing. If what I asked doesn’t mean much, I think I would feel a bit … yeah. ()

Figure 4. Soyeon's picture of the offline classroom. Note: In the picture, the teacher is standing in front of the board facing students and is asking whether everyone has understood what the teacher just said. Soyeon is seated in the middle, thinking she wants to ask something but decides not to say it because she does not want to stand out. Her friends, seated next to her, are both answering the teacher that they have understood what the teacher said.

Discussion and conclusion

Students’ experiences in an online classroom suggest that the material objects, technology, and complex power relations among human actors simultaneously play roles in constructing the online classroom space (Stratford, Stewart, and te Riele Citation2022). The findings in this study imply that the complex intersections between materiality and relationality need to be considered to identify students’ navigation of liminal spaces.

Whereas, in previous studies, materiality in the online classroom has often been suggested to generate limited learning experience for students (Lee, Min, and Park Citation2020) – and hence was proposed to be overcome by alternative approaches to utilising the material object on the part of human actors (Seo Citation2021) – the findings in this study suggest different ways of viewing the role of material objects. Material objects – such as the various technological functions provided in an online platform, and the screens through which participants interact – rather produce alternative ways of facilitating student participation in class or act as a platform that amplifies the influence of existing power dynamics. Technology, in and of itself, lacks inherent moral value; instead, it is entangled within broader networks of human and non-human elements that give rise to specific domains and territories (Grandinetti Citation2022). As such, the findings of this study highlight the significance of analysing the mutual entanglement of human and non-human influences in the materialisation of education and learning (Fenwick and Landri Citation2012).

The major contribution of our study is that it primarily attended to young people’s opinions about their experiences in online classrooms. Young people who participated in the study asked the purpose of the study and how their participation would impact change. Some participants were also interested in knowing why their school was chosen as a research case, which shows how young people care about the changes made in their lives. This study brings the voices of young people to the fore, positioning young people as social agents who are actively engaged in constructing the aims and meanings of learning during changes in schools (Collins and Coleman Citation2008).

Additionally, the findings of the study add to the empirical cases in which the roles of material objects in online spaces are analysed in a socio-material assemblage framework (Kalthoff and Roehl Citation2011). With the tools of the socio-material assemblage lens (Roehl Citation2012), we analysed how material objects contribute to constituting the spatiality of the online classroom by interacting with human actors, and how, simultaneously, human actors assign meanings to the use of material objects in the space. The findings of the study also suggest that not only the relations between materials and humans but also the power relations between human actors (Massey Citation1994) – which have previously been manifest in school space – contribute to shaping spatiality in online classrooms (Bork-Hüffer, Mahlknecht, and Kaufmann Citation2021).

We suggest future research avenues to address the limitations of the current study. Different experiences of participating in online classes may be expected depending on the class atmosphere, teaching methods of the teacher, and relationships between the students. We suggest that future studies conduct comparative analysis on multiple cases, including various experiences of online classes among multiple classrooms and schools. Additionally, special attention needs to be paid to the fact that participants in this study had to face an unprecedented transition period in schools while participating in the study. The participants were experiencing both physical and relational isolation creating unique contexts, which may have led to different levels and forms of confusion (Joo et al. Citation2021, 83). With students having returned to schools, we recommend conducting subsequent studies to track the changing perceptions of learning and school spaces before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Contribution

The authors equally contributed to this work.

Acknowledgement

Our sincere appreciation goes to the students and the teacher who have participated in the study and shared their valuable experience. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers on earlier drafts of this paper who have inspired us to improve this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Angelone, L. 2019. “Virtual Ethnography: The Post Possibilities of Not Being There.” Mid-Western Educational Researcher 31 (3): 275–295.

- Baek, B. B. 2020. COVID-19 and Education: Focusing on Online Education. Suwon: Gyeonggi Institute of Education.

- Baek, B. B., and J. Y. Jeong. 2021. COVID-19 and the Recommendations for the Improvement of Remote Classes. Suwon: Gyeonggi Institute of Education.

- Barker, J., P. Alldred, M. Watts, and H. Dodman. 2010. “Pupils or prisoners? Institutional geographies and internal exclusion in UK secondary schools.” Area 42 (3): 378–386.

- Baroutsis, A. 2020. “Sociomaterial Assemblages, Entanglements and Text Production: Mapping Pedagogic Practices Using Time-Lapse Photography.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 20 (4): 732–754. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798418784128

- Bork-Hüffer, T., B. Mahlknecht, and K. Kaufmann. 2021. “(Cyber)Bullying in Schools – When Bullying Stretches Across cON/FFlating Spaces.” Children's Geographies 19 (2): 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2020.1784850.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chae, H. J. 2020. “Googlification.” Today’s Education 56: 108–122.

- Collins, D., and T. Coleman. 2008. “Social Geographies of Education: Looking Within, and Beyond, School Boundaries.” Geography Compass 2 (1): 281–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00081.x

- Fenwick, T., and P. Landri. 2012. “Materialities, Textures and Pedagogies: Sociomaterial Assemblages in Education.” Pedagogy, Culture and Society 20 (1): 1–7. https://doi-org.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/10.1080/14681366.2012.649421.

- Fereday, J., and E. Muir-Cochrane. 2006. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (1): 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Gallagher, M. 2019. “Rethinking Children’s Agency: Power, Assemblages, Freedom and Materiality.” Global Studies of Childhood 9 (3): 188–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610619860993

- Garlen, J. C., D. Sonu, L. Farley, and S. Chang-Kredl. 2022. “Agency as Assemblage: Using Childhood Artefacts and Memories to Examine Children’s Relations with Schooling.” Journal of Childhood, Education & Society 3 (2): 122–138. https://doi.org/10.37291/2717638X.202232170

- Grandinetti, J. 2022. ““from the Classroom to the Cloud”: Zoom and the Platformization of Higher Education.” First Monday 27 (2): 2–7.

- Hadfield-Hill, S., and P. Christensen. 2021. “‘I’m big, You’re Small. I’m Right, You’re Wrong’: The Multiple P/politics of ‘Being Young’ in new Sustainable Communities.” Social & Cultural Geography 22 (6): 828–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2019.1645198

- Hedman, C., and S. Mannish. 2022. “Student Agency in Relation to Space and Educational Discourse. The Case of English Online Mother Tongue Instruction.” English in Education 56 (2): 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/04250494.2021.1955618

- Holloway, S. L., G. Brown, and H. Pimlott-Wilson. 2011. “Editorial Introduction: Geographies of Education and Aspiration.” Children's Geographies 9 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2011.540434

- Jo, Y. H., Y. K. Yun, and H. K. Lee. 2006. Culture and Education. Seoul: Korea National Open University Press.

- Joo, J. H., B. K. Kim, Y. J. Lim, S. H. Kim, S. R. Yoon, W. S. Kim, Y. J. Lee, and J. K. Kim. 2021. Post-Covid, A Study on the Educational Exploration and Practice Plan for Remote Classes: Focusing on the Teachers’ Experiences in Class. Seoul: Seoul Education Research and Information Institute.

- Kalthoff, H., and T. Roehl. 2011. “Interobjectivity and Interactivity: Material Objects and Discourse in Class.” Human Studies 34 (4): 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-011-9204-y

- Kim, H. J. 2021. “A Study on the Multidisciplinary Learning Efficacy of Online Classes – for Small Groups of High School Students.” The Korean Society of Science & Art 39 (5): 83–94. https://doi.org/10.17548/ksaf.2021.12.30.83

- Kim, D. H., and K. S. Park. 2022. “The Effect of Middle School Students’ Digital Literacy Competency on Teaching Presence and Intention of Class Participation in Online Physical Education Classes.” Journal of Korean Society for the Study of Physical Education 26 (6): 65–79. https://doi.org/10.15831/JKSSPE.2022.26.6.65

- Ko, Y. S. 20 May 2020. “Hee-Yeon Cho, “Harmony of Online-Offline Classes, New Path of ‘K-Edu’ in Covid Era” (조희연, “원격-등교수업 조화, 코로나 시대 ‘K-에듀’의 새길’”). Yonhap News. Retrieved from: www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20200520041900530?input = 1195 m.

- Lee, H. E. 2014. “Authentic Observation, or Voluntary Surveillance.” Korean Journal of Broadcasting and Telecommunication Studies 28 (2): 211–248.

- Lee, D. H. 2021. “Media Ecological Exploration of Digital Classrooms in the era of COVID-19.” Korean Journal of Broadcasting and Telecommunication Studies 35 (2): 98–139.

- Lee, H. J., Y. Min, and J. A. Park. 2020. “Reconceptualizing Education as Welfare.” Paper presented at the Third Gyeonggi Education Forum for COVID-19 and Education: from New Normal to Better Normal. Gyeonggido, September 15.

- Lee, Y. S., and S. J. Park. 2022. “A Case Study of Class Operation in an Elementary School during COVID-19 Period: Full Real-Time Interactive Classes for all Grades.” Korean Education Inquiry 40 (3): 223–252.

- Massey, D. 1994. Space, Place and Gender. Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

- Matthews, H. 2003. “The Street as a Liminal Space: The Barbed Spaces of Childhood.” In Children in the City, edited by P. Christensen and M. O’Brien, 101–117. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- McGregor, J. 2004. “Spatiality and the Place of the Material in Schools.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 12 (3): 347–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360400200207

- Moore, S. D. M., B. D. O. Jayme, and J. Black. 2021. “Disaster Capitalism, Rampant Edtech Opportunism, and the Advancement of Online Learning in the era of COVID19.” Critical Education 12 (2): 1–23.

- Oh, Y. B. 2021. “Possibilities and Limitations of Distance Instruction through Distance Instruction Case Analysis in Elementary Schools.” The Journal of Elementary Education 34 (1): 109–139. https://doi.org/10.29096/JEE.34.1.05.

- Pike, J. 2008. “Foucault, Space and Primary School Dining Rooms.” Children's Geographies 6 (4): 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280802338114

- Pike, J. 2013. “‘I Don't Have to Listen to you! You're Just a Dinner Lady!’: Power and Resistance at Lunchtimes in Primary Schools.” In Children’s Food Practices in Families and Institutions, edited by S. Punch, I. McIntosh, and R. Emond, 49–62. London: Routledge.

- Roehl, T. 2012. “Disassembling the Classroom–an Ethnographic Approach to the Materiality of Education.” Ethnography and Education 7 (1): 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2012.661591

- Selwyn, N. 2013. Distrusting Educational Technology: Critical Questions for Changing Times. New York: Routledge.

- Seo, S. J. 2021. “Analyzing Special Education Teachers’ Experiences on Synchronous Online Instruction in Special Education Classes Within Inclusive High Schools.” Special Education Research 20 (3): 55–83. https://doi.org/10.18541/ser.2021.08.20.3.55

- Soja, E. W. 1985. The Spatiality of Social Life: Towards a Transformative Retheorisation. London: Palgrave.

- Stratford, E., S. Stewart, and K. te Riele. 2022. “School Data Walls: Sociomaterial Assemblages to aid Children’s Literacy Outcomes.” Children's Geographies 20 (3): 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2022.2029348

- Thomson, S. 2005. “‘Territorialising’the Primary School Playground: Deconstructing the Geography of Playtime.” Children's Geographies 3 (1): 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280500037224

- Variyan, G., and K. Reimer. 2021. “Academic, Interrupted: Exploring Learning, Labour and Identity at the Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Studies in Continuing Education 44 (2): 316–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2021.1950670

- Webster, J. P., and M. da Silva. 2013. “Doing Educational Ethnography in an Online World: Methodological Challenges, Choices and Innovations.” Ethnography and Education 8 (2): 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2013.792508.

- Wood, B. E. 2012. “Crafted Within Liminal Spaces: Young People's Everyday Politics.” Political Geography 31 (6): 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.05.003

- Yun, J., and B. C. Kim. 2018. “How Does School Succeed? A Qualitative Case Study on the Shared Leadership of ‘A’ Elementary School Teachers.” Korean Journal of Educational Administration 35 (4): 191–222. https://doi.org/10.22553/keas.2018.36.0.0.