ABSTRACT

In Asia, high levels of malnutrition threaten the health and livelihoods of millions of households. This paper concentrates on linkages between agriculture and nutrition in Afghanistan where food and nutrition insecurity are increasing and agricultural sustainability is increasingly compromised by climate change. We explore seasonal patterns of food production and consumption in the remote and robust ecological environment of Shah Foladi, Bamyan Province. Analysis of qualitative data from household interviews in eight villages has provided a wealth of insights into the seasonality of diets. Even within a broadly homogeneous environment, households were found to be markedly heterogeneous in respect of their assets, production, market, finance and employment strategies. The so-called ‘lean season’ was found to vary accordingly. Nevertheless, a general lack of dietary diversity during much of the year is likely to cause micronutrient malnutrition, especially for the vulnerable groups of children, adolescent girls and women. Potential interventions are proposed which need to account for the local context in order to overcome the natural and political constraints. These strategies include agricultural innovation and multi-sectoral policy approaches. In the end, reducing national insecurity is a pre-requisite for sustainable improvement in nutrition-sensitive agricultural development.

Introduction

‘Assuring global food security’ is among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for the year 2030. About 800 million people today still lack food security (IFPRI, Citation2016), and for many the situation is worsening due to factors such as conflict and climate change (FAO et al., Citation2018). Food security is (too) often referred to as the adequate consumption of macronutrients, measured in Kcals of food energy per capita (see, for example, Ritzema et al. (Citation2017) who used a simple energy-based index of food availability as an indicator of dietary adequacy in East and West Africa). Nutrition security focuses on micronutrient-deficiency diseases caused by inadequate intake of vitamins and minerals. This is contemplated in SDG2 but not effectively prioritized, despite calls for refocusing food systems on the quality of food (Pingali, Citation2015). Both food and nutrition security are intimately linked to sustainable production and consumption (SDG12).

It is estimated that 2 billion people suffer from micronutrient deficiencies, mostly attributable not to lack of food, but lack of nourishing foods that provide essential micronutrients (CDC, Citation2018). Micronutrient deficiencies in the first 1000 days of life cause stunting, which is an indicator of irrecoverable damage to children in respect of growth and development, impaired physical, intellectual, social and reproductive functions, increased susceptibility to other diseases, and premature death. Recent research on stunting has identified significant gender-based impacts disfavouring girls (Himaz, Citation2018). This signals the catastrophic intergenerational consequences of micronutrient malnutrition.

In the last 10–15 years much research effort has been expended on exploring the nature of, and need for, dietary diversity to overcome micronutrient malnutrition. For rural populations, diverse systems of agricultural production have been found to be an important factor in enhancing dietary diversity and improved nutrition outcomes. However, agricultural production diversity does not necessarily lead to dietary diversity, and markets are an important source of foods even for rural populations. Own-food production and nutrition outcomes are varied or indeterminate, conditioned by sales of nutritious foods on the one hand, and market purchases of foods enabled through income from employment on the other (Jones, Citation2017; Jones, Shrinivas, & Bezner-Kerr, Citation2014; Masset, Haddad, Cornelius, & Isaza-Castro, Citation2012; Pellegrini & Tasciotti, Citation2014; Powell et al., Citation2015; Sibhatu, Krishna, & Qaim, Citation2015).

Changes in seasonality as a likely consequence of climate change are threatening livelihoods and food security of households dependent on their own agricultural production (Savo et al., Citation2016). More specifically, seasonality promises to be an important factor affecting nutrition sufficiency (Sibhatu & Qaim, Citation2017; Zanello, Shankar, & Poole, Citation2019). However, the nature and effects of seasonality on the availability, affordability, and consumption of nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables are neglected in major studies (Miller et al., Citation2016).

Afghan development indicators

While some of Afghanistan’s development indicators have improved recently, others have stagnated or worsened. Food insecurity has increased from 30% in 2011–2012 to 45% in the recent Living Conditions Survey 2016–2017. shows key indicators drawn from CSO (Citation2018) which illustrate household-level socio-economic development parameters.

Table 1. Selected key indicators of nutrition and development in Afghanistan.

The state of nutrition in Afghanistan

Malnutrition is one of the most serious health and development problems in Afghanistan: the latest National Nutrition Survey (NNS) confirms high rates of stunting among vulnerable groups such as children under the age of five (nationally 40% and in certain provinces over 70%) (UNICEF, Citation2014). Additionally, micronutrient deficiencies are strongly implicated in malnutrition among women and adolescent girls (Flores-Martínez, Zanello, Shankar, & Poole, Citation2016).

A recent study of the geographical differences and determinants of nutrition status at district-level among children and women of reproductive age in Afghanistan identified diverse individual, household, community, and environmental risk factors (Akseer et al., Citation2018). There was marked heterogeneity between regions but Akseer et al. did not explore the seasonal differences explored in this paper. Generally, food insecurity was found to be higher in the more geographically extreme regions.

In the Central Highlands region, in 2014, food insecurity was reported to be lowest in the harvest season at 32%, and increased to 38% in the ‘lean season’, reaching 56% in the post-harvest period (CSO, Citation2014, p. 180). In Bamyan Province food insecurity is among the highest in the country, reported as 72% (CSO, Citation2016). Less well understood are the varying levels of nutrition insecurity due to micronutrient deficiencies, that is, the variations through seasons, regions and population groups of a qualitatively inadequate diet.

Dietary diversity

Low dietary diversity is one important dimension of nutrition insecurity. A very high dependence in Afghanistan on wheat consumption and the vulnerability of supplies to erratic rain-fed production is widely acknowledged (GoIRA, Citation2012; MAIL, Citation2016; Obaidim et al., Citation2015; Poole, Echavez, & Rowland, Citation2018). In fact, a diet of bread and tea is the staple. According to CSO (Citation2018) 41% of the rural Afghan population suffer from low dietary diversity. summarizes the dietary diversity scores.

Table 2. Dietary diversity score (DDS) (mean) and percentage of households with low dietary diversity.

In a number of remote provinces where geographical conditions are harsh, the diets of more than 70% of households exhibit low dietary diversity:

The population with poor consumption patterns tend to only occasionally eat meat, fish and eggs, dairy and dairy products, and nutrient-rich foods, such as pulses and nuts. Their diet predominantly consists of wheat, oil and sugar only. Population with borderline consumption – in addition to eating cereals, sugar and oil almost every day – eat vegetables every other day, on average eat one day a week from each of the food groups of fruits, dairy products, pulses and meat, fish or eggs. Population with acceptable food consumption eat from meat, fish or eggs and from pulses approximately two days per week, from dairy products five days a week and from vegetables three to four days a week. (CSO, Citation2018, p. 132)

These data only hint at the variability in diets throughout the year and the impacts of extreme conditions on production and consumption.

Agricultural systems and diets in Shah Foladi

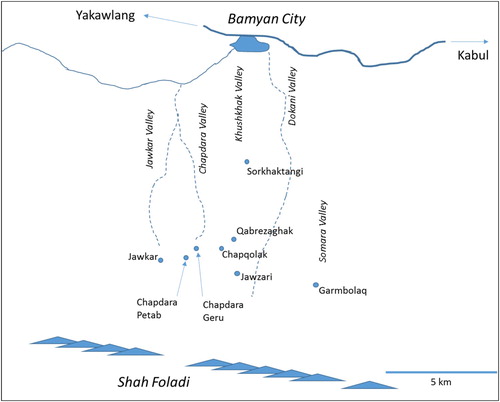

The Koh-i-Baba mountain range in Bamyan Province rises to its highest at Shah Foladi Peak (5050 m), immediately south of Bamyan City ( and ). In 2017, the Afghanistan National Environmental Protection Agency declared part of the region as Afghanistan’s most recent protected area covering 2700 km2:

In the midst of an arid country, the Shah Foladi area is covered with snow throughout most of the year and is a nationally important watershed … Much of the area also consists of high elevation rangelands that support diverse wild plant and animal species, and provide the local population with vital plant species for fuel, food, and medicine, and the means for animal production. (UNEP, Citation2017)

Using irrigation water from the mountains, Bamyan has become the centre of a thriving potato industry which has changed production patterns and altered household economics and diets significantly in the last 15 years (potatopro.com, Citation2017; Ritchie & Fitzherbert, Citation2008). For many small-scale producers, annual legumes and pulses have been replaced by potato production as a staple and cash crop to the extent that potato is monocropped within a small radius of Bamyan City. This gives rise to inherent threats from plant diseases and market risks in such a vulnerable and fragile agro-ecological and socio-economic environment (Ritchie & Fitzherbert, Citation2008).

For Afghanistan as a whole, the harvest season is from May to July (sawer-jawza-saratan) for the main staple cereals of wheat, maize and barley (). The post-harvest period is from August to mid-December (asad-jadi), and pre-harvest (the so-called ‘lean’ season) is from mid-December to April (qaws-sawer). However, there is considerable variation throughout the country. Bamyan experiences ‘severe winter conditions’ and a ‘lean season’ of up to six months lasting from November to April (CSO, Citation2014, p. 180). The increasing frequency of meteorological disturbances affects production and livelihoods in a region already under climate stress (OCHA, Citation2018). With limited food storage and preservation, dietary diversity is compromised by highly seasonal production of nutrient-rich foods such as fruits and vegetables, dairy produce and other animal-source foods. Minimal sources of winter employment and poor logistics limit the market availability of diverse foods and impair economic and physical access to markets.

Table 3. Afghan and Western months.

Methodology

The research approach

This research in Bamyan aimed to elucidate seasonal drivers and patterns of food production and marketing, purchase and consumption in Shah Foladi. The study reported here was a small-scale qualitative exploration of households’ experiences of food and nutrition insecurity. Fourteen household interviews were used to elicit recall data on annual food production and consumption, as well as agricultural livelihood practices and intra-household dynamics. Given the broad understanding of seasonal dietary patterns from secondary data reported above, the intention was to understand what factors affected food consumption and the limited dietary diversity in the ‘lean’ season.

Household food consumption surveys are the single most important source of data on dietary adequacy but there is no single approach, and there are many shortcomings in practice (Zezza, Carletto, Fiedler, Gennari, & Jolliffe, Citation2017). Adapting the standard approach of the World Food Programme and other organizations (World Food Programme, Citation2008), the intention was to investigate seasonal availability and frequency of consumption of twelve major food groups.

The common approach of 24-hour recall was rejected because without multiple surveys, it fails to capture any sense of seasonality (Sununtnasuk & Fiedler, Citation2017). Similarly, diaries were not considered feasible in a largely illiterate population. In some circumstances recall data over long periods have been found to have a useful degree of accuracy (Berney & Blane, Citation1997). Whereas the standard approach uses a seven-day period, recall data over a one year period is likely to have a low level of precision. In fact, both recall data and diary data on food consumption and expenditure have been criticised as inaccurate (Ahmed, Brzozowski, & Crossley, Citation2006; Brzozowski, Crossley and Winter, Citation2017). Thus the limitations of the methodology used are significant. For these reasons we did not ask about food quantities and consumption by an individual household member, and we do not try to arrive at a definitive food consumption score.

Another important limitation concerns any conclusions about the adequacy of the diets recorded. The adequacy of diets can be inferred from estimates of the nutrient content and frequency of consumption of foods. However, it is not possible to point to individual nutrition requirements and deficiencies. These will depend on an individual’s age and stage of development, level of activity, gender, health status, and interactions between these factors, and the specific micronutrients of concern. Secondly, obtaining precise data on nutrient intakes requires a sophisticated level of experimental design that was impossible under the prevailing research conditions. Ultimately, physical insecurity due to the ongoing conflict limited the ambition of the research design.

There are two reasons to argue for cautious acceptance of the findings: first, after the age of six months, and almost definitely above the age of one year, all household members were reported to eat the same foods, irrespective of age, gender and other variables, such that a ‘household diet’ is a valid concept. Secondly, through the validation process described below, workshop participants and stakeholders endorsed the data on patterns of consumption.

Questionnaire design

Prior visits to Bamyan by the research team and discussions with local people oriented the research. The household questionnaire was then designed and tested by SOAS University of London and staff of the Bamyan NGO, Ecology and Conservation Organization of Afghanistan (ECOA) who were familiar with the region and the individual villages, and known personally to many of the households. It covered household demographics; agricultural production systems, storage and sales; labour inputs; and food consumption and purchase patterns. It was implemented in the Dari language by local staff of ECOA. Notes taken during the interviews were translated into English and entered into the questionnaire for analysis by the research team of ECOA and SOAS University of London. ECOA were supported significantly throughout by the national office of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Local permissions were sought from provincial and District authorities, and data collection was conducted following the ethical protocols of ECOA and UNEP.

Implementation and sampling

Fieldwork was conducted between August and October 2016. Partly for reasons of feasibility and prevailing insecurity, a small-scale qualitative approach was used. Sampling was purposive. Eight villages in the Shah Foladi area were selected: Chapdara Geru, Chapdara Petab, Chapqolak, Jawkar, Jawzari, Qabrezaghak, Somara Garmbolaq and Sorkhaktangi (). They were from villages with which ECOA was working on related environmental development topics. indicates important geographical features of the villages selected: altitude (metres above sea level) and distance to market (kilometres). Household descriptive statistics follow in . Individual households were selected by the NGO in discussion with the head of the Community Development Council to cover the range of poorer to better-off households, and people with whom there was a relationship of trust regarding the reliability of data supplied. While this familiarity introduced potential bias by interviewers, it also served to check the veracity of respondents.

Table 4. Geography of study villages.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics (n = 14 households).

depicts the locations of the villages between the city and the mountains of Shah Foladi.

Interview dynamics

In each village, a discussion was held to inform residents of the purpose of the research. There were four interviewers, two men and two women. After the initial village meeting, the men in the selected households were interviewed by the male interviewers and the women were interviewed separately by the female interviewers. The interview process took up to two hours per household. The interviews with the men elicited only general comments on the topics of food production and consumption. In contrast the interviews with the women elicited more precise details about consumption patterns, food sourcing and intra-household distribution. In one household case, women were not allowed to participate.

Comparison of data for the selected households with public data such as CSO (Citation2018) suggests that the households were well within the normal distribution ( cf. ). Data quality were scrutinized at a one-day knowledge exchange event in July 2018. This meeting in Bamyan City included about 55 people, approximately equally women and men, from participant and non-participant households, staff from other NGOs working in Bamyan and neighbouring provinces. Besides discussing the findings in greater depth, the exchange was a data validation exercise. The consensus was that the data were reliable for much of the Central Highlands region of Afghanistan.

A second higher-level knowledge exchange event was held in Bamyan City in July 2018 with national and international stakeholder and policy organizations. Participants included staff of NGOs, some of whom had attended the previous meeting, provincial government officials and provincial staff of ministries of the Government of Afghanistan, including the Department of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock and the Department of Education. A third workshop was held in the British Embassy in Kabul, also in July 2018, with DFID staff and members of some NGOs.

Conceptual framework

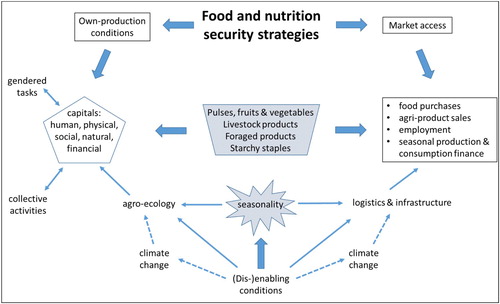

The findings which follow have been presented within a formulation of the sustainable livelihoods framework adapted to the Afghan context and applied to the objective of food and nutrition security (). It draws on the fundamental concepts that have enjoyed widespread and fruitful use in the analysis of sustainable livelihoods (Carney, Citation1998; Chambers & Conway, Citation1992; Donovan & Poole, Citation2013; Donovan, Poole, Poe, & Herrera-Arauz, Citation2018; Dorward, Poole, Morrison, Kydd, & Urey, Citation2003; Poole, Citation2004; Scoones, Citation2009).

Nutrition security is achieved through the consumption of foods that constitute a diverse and nutrient-rich diet. Availability can be secured through own-household production and access to markets. Own-production is a function of endowments of household capital assets and natural and socio-economic conditions. Even people in remote rural regions source part of their food requirements through access to markets. Gender roles and collective activities also influence production. Affordability of nutritious foods depends on financial resources for purchases which are derived from agricultural sales or engagement in labour markets. Seasonal credit can play an important part in both facilitating production and smoothing consumption.

Seasonality and climate change are represented as major (dis-)enabling factors affecting production and consumption. Seasonality also affects market access for a range of goods and services besides food, including production inputs, income from sales and employment. The data which follow illustrate many of these determinants of food insecurity and nutrition vulnerability.

Research findings

The findings draw on the transcripts of the interviews and use illustrative quotes of respondents. It is both the norms and the differences or outliers within the sample which are informative, and the results presented below represent the range of responses. Household locations are given but identities are anonymised.

Data on production patterns, food and nutrition security strategies are presented after the household characteristics, and have been mapped onto the framework presented in in terms of own-production, market engagement, impacts of seasonality and food consumption, distribution and decision-making.

Household characteristics

shows descriptive data for household composition, indicative percentage figures for income sources, and arable and livestock production variables. Compared with the key indicators for Afghanistan presented in , the households interviewed in Shah Foladi had more adults and fewer children under the age of 15 years.

Education levels were low, with only two households [8 and 12] having literate adults. One household [2] included a graduate of the local university. Children – boys at least – mostly attended school, subject to weather and working conditions, but access difficulties were a real constraint, especially for girls:

It is very important for our boys to go to school. [9]

Due to remoteness of the village, most of our children can’t reach school and girls can’t progress to higher levels of education. [3]

Own-production strategies

Arable systems

Arable systems have intensified in response to recent market incentives, and become increasingly profitable:

In the past, people cultivated barley, beans and wheat that had lower profits but recently people cultivate potatoes and use agrochemicals that didn’t exist before. Nowadays people have increased production and household income greatly. [6]

Although farm sizes were small, one limitation was the lack of water, cited by a number of respondents, affecting major crops and also fruit and vegetable production:

Due to lack of an irrigation system we cannot use most of our farmland. [11]

Mostly the villagers don’t grow vegetables due to lack of irrigation. [7]

All households but one in the sample cultivated wheat and potatoes for own-consumption and sale. Barley was cultivated by half the households and oats by only one. Production of grains and potatoes was generally rotated, and in most cases benefited from the application of natural and/or inorganic fertilizers. Seeds for staples were sometimes saved, sometimes purchased:

We buy seeds from the bazaar and use local seed. [11]

Livestock systems

All households but one kept livestock: a cow, a mean of 10 sheep per household and fewer goats and poultry. Half of households had a donkey, important for land cultivation and personal transport. Only one had an ox. Livestock were grazed on the rangelands above the villages for seven months (sheep) and five months (cattle), and otherwise over-wintered on stored fodder within the household compounds. All households but one cultivated alfalfa for livestock feed, and fodder was also collected from the rangelands for winter use. There was a keen awareness of the need to manage grazing to ensure conservation:

We do not use one area for grazing only; for livestock we change the grazing area each month to preserve the rangelands from over-grazing. [1]

Herding livestock was often undertaken by children, both boys and girls, but milking and processing were almost exclusively women’s responsibility. Milk was collected from both cows and sheep and commonly made into different types of cheeses, oil and yoghurt. Milk and derived products were almost always consumed entirely by the household.

Gender and labour

In most cases, arable labour was provided by the household. One household [12] exceptionally employed a shepherd, although there were children who could have assumed this responsibility. In many households, agricultural responsibilities were shared by men and women. For one household, labour patterns were more gendered and restrictive:

Women in our family have a big part in agriculture, from preparing the land to collecting/harvesting the produce because this family has no workers and also not enough money to employ workers. [3]

Women in our family have no roles in agriculture because it is not part of the household activities. [10]

Communal operations

The sense of community was evidenced by responses about arduous and time-bound tasks shared between households, activities that have a more explicit social value, and those like transportation that can be made more efficient through exploiting scale economies. Nevertheless, communal operations were said to be reducing in importance:

For harvest all the village works together. For bringing fertiliser and food from the bazaar, villagers also get together. [2]

There are collective activities for potato production and monthly transportation for bringing their needs from the bazaar, and also for fuelwood collection they hire animals twice per year. [4]

In the past, around 10 years ago, there were a lot more communal works like fuel collecting, harvesting, buying food from the bazaar, but nowadays, mostly fuel collecting and harvesting is done by individual households. [11]

Market engagement

Engagement with product, labour and financial markets

Much of the households’ cash income was derived from agriculture. One outlier did not engage in agriculture but depended entirely on income from full-time employment. This household owned little land and borrowed a plot to grow potatoes. An unusual characteristic was that they migrated to the bazaar during the winter months:

Because we don’t have a lot of land, a small plot is borrowed to meet the needs of the family … Due to cold weather and bad conditions of the roads our family moves near the market in winter to meet its financial and dietary needs by working in the market and coming back to the village in the spring. [13]

For two other households, employment contributed 70% and 20% of income respectively. In one other household, there was a school teacher and a part-time worker in the hotel sector, whose employment contributed 60% of household income, as well as the one son studying at Bamyan University [2]. Other households engaged in seasonal labour when possible.

Interviewees were not asked about credit or financial services, but from the responses of five households, it was evident that borrowing from storekeepers in the bazaar and from friends was an important strategy:

Sometimes whenever physical cash is not available we take money from a friend or borrow from shopkeepers. [14]

Sales of potatoes were important in clearing debts. Another outlier was the household of a father and mother and three adult children. The father was a tinsmith whose sales in the bazaar over a two month period contributed 70% of annual income. The remainder of income and subsistence was derived from agriculture, including a significant plantation of 34 fruit trees.

Produce sales

Potato harvesting took place in September (sonbula-mizaan) and for one household [2] totalled 1800 kg. Sales were made later, in aqrab, or in the mid-winter period five or six months later. Sheep sales were made in August (asad-sonbula). Poor logistics affected the mode of agricultural sales, such that most households preferred to avoid the costs of transport and sell in the village to local traders. Most households gained price information from visits to the bazaar, and from friends and neighbours. Some households were aware that making sales locally incurred a price penalty:

People do not need to go to market; they sell their crops to their village traders. They do not need to bring their crops to the bazaar … Because of the remoteness to the market, people sell their product two times cheaper than its real price, to local village traders. [1]

Impacts of seasonality

Seasonality was an acute fact affecting productive activities and other aspects of life. Employment, household tasks, access to fuelwood and travel were seriously limited:

In winter our children [usually the daughters] face horrible problems and accidents bringing water from the water source to home. [13]

During the winter months there is very heavy snow in the village and the weather is very cold while we do not have enough facilities and we are suffering from this condition. In the other seasons of the year, life is good, we can farm our land, we can go to the bazaar, we can work and also we do not need a lot of fuelwood. [6]

We try to cook food that needs less firewood. At the end of winter and start of spring usually we face lack of firewood because the stored firewood finishes and due to rain we can’t gather so we try to use less firewood. [6]

Seasonality was the primary determinant of food consumption patterns, as indicated by one household whose experience was common. For other households, there was not a problem of prolonged hunger:

The pattern of food consumption varies across the different months of the year, according to seasonality and market access. Most foods are not available or accessible in winter. [10]

We have not faced such a time [of hunger], but some families have faced this in the past. Nowadays people deal with hunger when crops are running low at the end of winter, but we rarely face lack of food. [2]

Food storage and market purchases

Grains were stored in the house, and potatoes also, if they were not stored outside in a pit, for three or four months (qaws, jadi, dalwa and hoot). Potato losses due to inadequate storage were cited frequently as a problem:

Most of the people are storing crops inside the home, but some prepare a special place like a cellar that is mostly used for potato. [11]

Lack of suitable storage and long cold winters cause crops to spoil. [1]

Essential items that could not be home-produced were sourced from the bazaar in Bamyan City because there were no local retail outlets. Access was either on foot or donkey, or by motorbike or the shared hire of a car. Usually it was the men who went to the bazaar, but not always. Poor logistics and insecurity were reported to impede access. Even summer visits to the market for purchases could be as infrequent as every two or three months for some households:

For purchasing salt, tea, cooking oil, shopping is done at the bazaar. [14]

All family members can go according to their needs, but generally men go. [5]

Usually due to cold weather and snow falling in winter, roads are blocked causing prices to increase and sometimes bad security and attacks on the highways cause the same problems. [7]

During Ramadan or during Eid we use our own products but sometimes items are purchased from the market. [12]

Food prices

Seasonal prices for staples, like vegetables and fruit, were said to double, or more, between summer and winter:

During the spring potatoes are very expensive, the price is almost double compared to the other seasons … prices depend on the season: the fruits that come to the bazaar during the warm seasons like grapes are cheap, but become expensive during the other seasons – almost double the price. Vegetables are the same as fruits. [5]

One household [10] commented that seasonal prices were too high to permit purchases of potato in July-August before harvest (asad), and of meat in February–March (hoot). Savings, labour and credit that contributed to household budgets were supplemented by product sales, of livestock in June–August (saratan and asad), even into September–October (sonbula and mizaan); and of potatoes in August–September (asad and sonbula).

Impacts of seasonality on mobility and market access

The influence of seasonality on daily life was fundamental. Weak public infrastructure including lack of all-weather roads and bridges affected households in diverse ways, for example:

It is very hard for us to go to the bazaar during the winter but it is not impossible. The weather is very cold in this area and during the long winter our daily activities decrease and some of the days are fully taken up by ploughing snow from the roof. During the warm seasons we can do our daily activities regularly; working on the land, going to the bazaar, and planting. [7]

Due to the lack of road this village has no access to car transportation and the private car costs a lot of money to even come into the village which is a big economic problem, so if we had proper roads the hire rates of cars would be lower and we would have access to clinics and the market easily. [6]

The ‘lean season’

Respondents were aware of the significance of seasonality on dietary diversity, but prevailing conditions constrained food choices. The majority of households were primarily concerned about hunger, and food needs were met by a basic daily diet of bread and tea, consumption of which was accompanied by sugar, sweets and occasional luxuries like chocolate:

The three or four staples that make up the diet never change … All family members drink tea with chocolate and use sugar with tea in the mornings. [12]

Most fresh foods like vegetable, fruit, dairy products and wild foods are all heavily dependent upon seasonality. [8]

Households gave varying responses concerning the ‘lean season’. This was discussed at the workshop in July 2018, but a definitive and common calendar could not be deduced, as the following quotes indicate:

Hunger occurs at the end of winter (hamal) when there is little storage left. [9]

The spring season (hamal and sawer) we face prolonged hunger because all stored produce is finished and that is the worst season when there is no money to purchase things and no time to go to market and borrow products. [6]

Food stores finish in June and July (jawza and saratan) before new crops are harvested. People in this village suffer hunger all year round and mainly eat bread, rice and potato. [1]

August and September (asad and sonbula) are the hungry months because the stored products are finishing and new products are not available. [13]

Depending on farm and household size, stores of own-produced wheat and potatoes were exhausted at different rates, sometimes months before the new harvest in August–September (asad and sonbula). We note, therefore, that the concept and timing of the ‘lean season’ varied between households. ‘Hardship’ from November–February (qaws, jadi, dalwa, and into hoot) was one defining element, but ‘hunger’ became relevant once food supplies ran low. Thus the ‘lean season’ set in once food stores ran low, before the bazaar could be accessed for purchases and credit, and before the labour market opened (March onwards). Nutritional insufficiency is yet another dimension, referred to below.

Depending on the availability of financial resources, ‘hunger’ could persist well into the new growing season – potatoes being planted from March–April (hamal), and vegetable crops somewhat later. The new harvest brought definitive relief from hunger.

In conclusion, the differences in household livelihood capitals and strategies appear to explain this variation. Context – or ‘situational socio-economics’ – matters.

Seasonal food consumption patterns

Food consumption by categories

aggregates the data from all 14 households interviewed and summarizes the ranges of responses concerning the sources and frequency of consumption of different items from the major food categories throughout the year. The sources of foods are own-production and/or purchased from the bazaar in Bamyan. Seasons are broken down into quarters. The frequency of consumption is expressed as an aggregate of responses (with some outliers marked ‘?’).

Table 6. Source and frequency of food consumption by category.

In brief, the tendency to eat starchy staples more frequently is evident. Similarly, the tendency to eat the nutrient-rich categories of fruits, meat eggs, and dairy much less frequently is evident. Consumption of pulses was zero except for one household, and then very infrequent. Nuts and seeds such as walnuts and almonds, which are an important and nutritious category of products in Afghanistan, were also rare luxuries.

Foods in the category ‘oils/fats’ was in the form of cooking oil, and butter made from own dairy production and purchased, and was eaten daily. Sugar and sweets provided pleasure and energy, as well as predisposing consumers to health hazards. Herbs foraged from the rangelands over a very short spring/summer season were eaten raw and incorporated into cooked dishes. Besides flavour, they were considered to contribute nutrients (e.g. vitamin C) and confer medicinal benefits.

Overall, it is evident that the consumption of nutrient-rich foods was at best occasional in the autumn and winter, and very infrequent in spring.

Following , we present data from interview transcripts about the major food categories, which illustrate salient points about seasonality and frequency of consumption.

Vegetable and fruit consumption: A wide range of vegetables was accessible in the bazaar throughout the year, but in the winter, according to interviewees, at a much elevated price and at the cost of arduous travel. Home-grown vegetables (carrot, radish, onions) were available May–June onwards (jawza), eaten once or twice, or sometimes more during the week. Carrot, radish, onion, turnip, leek were purchased by most households from the bazaar, maybe once or twice a month during the summer (saratan, asad, sonbula).

For the few households who consumed home-grown fruits (apples and apricots) these were, like bazaar fruit, available late in the summer. Purchased fruits were largely watermelon, apples, apricots, grapes and melon. Dates and pomegranates also figured among the fruits consumed. However, most households consumed fruits only rarely, maybe once per month in the summer. For one household, most fruits and vegetables were not eaten more frequently than once a month, and only in summer [12]. Foraged foods were accessible from the rangeland in spring and summer months, but were consumed infrequently, but by all households except two in Jawkar [7 and 8].Footnote1 Among wild plants, each only available for one month, those cited included: shirish (Verbascum spp), bolo, chokri (Rheum ribes), sharsham (Brassica spp), gandomak. Footnote2 The dietary contribution of the consumption of herbs, albeit small and highly seasonal, should not be underestimated. Responsibility for collection of herbs was shared:

Men and women both collect herbs, so according to their schedules they are responsible for natural resources an almost even amount. [6]

We rarely eat meat because meat is expensive.[5]

For the Eid celebration all villagers get together to purchase a cow or sheep and slaughter it to share with all the families. [8]

In Ramadan the diversity of food becomes better; we use meat, fruits and vegetables that are mostly purchased from the bazaar. Also during the Eids [3 festivals per year] people are using the best foods. In the Moharram month all the villagers are using kocha which is a kind of local food made from wheat and meat in the mosque. [4]

Only one household reported that dairy products were consumed most days for 11 months of the year [5], while another claimed to consume a range of dairy products throughout the year [14]. This could imply storage of less perishable products such as hard cheese, but this family was apparently better-off, exceptional in migrating towards Bamyan City during the winter and in having a trade and income outside agriculture, so more likely was able to purchase dairy products throughout the year.

Pulses, nuts and seeds: Pulses were not grown by any households, and were bought from the market by only a few households and consumed no more than once per week, more commonly once per month. For some households, consumption was less frequent or zero. Consumption of nuts was only at festivals, but one village had planted almond trees which were not yet ready for harvest. For one household, nuts were consumed on special occasions:

… around once/ month or according to economic situation and at some ceremonies like Eid, also for guests and other events. [14].

Food distribution

In some households, no distinction was made in diets for different members who might be nutritionally vulnerable. Other households showed some differentiation:

There is no special food for women, lactating mothers, adolescent girls, children. They eat the same food because there is no choice to eat differently … [For infants] from 9–10 months age semi-solid foods start and from 2 years of age solid food is introduced. [11]

Usually breast-feeding mothers eat more meat, oil and vegetables, and more fruit and vegetables for adolescent girls and children and infants. [14]

For the first 10 days after child labour, women eat a kind of food called kashkaw (a stew of vegetables, beans and noodles). After that, all family members eat the same food. [1]

Solid foods were introduced to infants from the age of six months or one year. Thereafter the starch-based diet supplemented by tea was dominant throughout the year for all members of the household, shared equally without regard to age or gender.

After 6 months semi-solid foods are introduced and after one year children are given the same food as the rest of the family. [2]

All family members use the same food … All family members drink tea with chocolate and use sugar with tea in the morning. [5]

Women’s role in decision-making

Food distribution was the responsibility of women:

Food is distributed by the mother of the family and she is the only decision maker, she tries to give more food to men because they work hard and need more energy and other family members eat according to their needs. [6]

Production, harvesting, sales and storage decisions are critical household functions. In terms of decision-making, often responsibilities were shared by women and men, but final decisions were the responsibility of the male head of household:

Men in this family make decisions with his wife’s advice but the man is the main decision maker according to his economic status. [3]

Women do 50 per cent work of cultivation but unfortunately women don’t share in the decisions and men make decisions about what to grow on the land. [6]

On decisions regarding food storage, purchase and food management, both men and women were involved, and often decisions were shared. Commonly it was said:

Men and women control, but men are the main decision makers … We can say it’s a kind of group work, for example women give ideas about food to purchase and men purchase them from bazaar, according to their finances and the distribution of the food is done by the women, who prepare the food. [6]

In other households, decision-making was more strictly defined. Age was also cited as a factor in exercising decision-making power over household food storage and distribution:

Food production is the man’s job and household caring is the woman’s job. [11]

Elders mostly make the decisions but decisions are made collectively; mostly the grandmother in consultation with the men, and food distribution is up to women, especially the grandmother. [1]

Discussion and conclusions

Livelihoods in central Afghanistan

How seasonality affects livelihoods in Shah Foladi is easily understood in general terms. In any year, extreme temperatures restrict the growing season to half the year or less. Food and feed for people and livestock become restricted during the long winter. Employment opportunities are constrained and limited financial flows need careful management. Household maintenance activities, such as collection of fuel and water, become arduous, even dangerous. However, households are heterogeneous in structure and assets, and formulate different strategies in managing their common environment. Hence, the precise impacts of seasonality on household livelihood and nutrition strategies have not been well documented hitherto.

This research responds to the call for context-specific knowledge of food consumption patterns and nutrition vulnerability (Gillespie et al., Citation2019). Although the sample of cases was small, the households have provided a wealth of data on the seasonality of diets and the sustainability of rural livelihoods in the robust conditions of central Afghanistan.

In this final section we make some specific observations about livelihoods in Shah Foladi:

There was a high level of dependence among households interviewed on own-production, requiring land, irrigation and agricultural inputs as important factors of food production. Household food strategies also involve access to urban markets, informal seasonal finance for production and consumption, paid casual labour and substantive employment in trade.

Food and nutrition insufficiency are marked during the lean season. For infants and children, six months of micronutrient insufficiency may cause significant damage. However, we have also noted that the ‘lean season’ does not occur at a fixed period of the calendar, but is a phenomenon of both ecology, production systems and household socio-economics. People are likely to become malnourished at different times and for different reasons.

Food storage – of grains and potato – is fundamental to survival, but is finite. For some households, hunger persists into the new growing season with potentially debilitating effects as labour demands increase. But hunger and micronutrient malnutrition are neither co-terminous nor necessarily contemporaneous. The monotonous starchy diet of bread, potatoes and tea is relieved by seasonal access to nutrient-rich foods such as fruits, vegetables, wild herbs and dairy products which become available through household production, collection from rangelands and access from markets even while hunger – or energy insufficiency – persists.

Savings and borrowings matter for all household expenses, but are essential strategies for easing the constraints on consumption and for enabling purchase of productive inputs. Sales of agricultural produce such as potato, grains and livestock occur in different seasons and ease consumption constraints as well as enabling debt repayments.

Physical remoteness, poor infrastructure, extreme weather and personal insecurity hinder access to markets for products, food, labour and finance. Provision of, and access to, basic public services such as health and education limit individual and household well-being, opportunities and potential in the short-, medium- and long-term.

Prospects and recommendations

Natural and political constraints: Agriculture and livestock production are threatened by the impacts of climate change which include more extreme temperatures, more erratic precipitation, and increasing likelihood of disasters (FAO et al., Citation2018; Lloyd et al., Citation2018). One particular threat to agriculture and nutrition in Afghanistan is over-grazing of rangelands, causing loss of wild foods for human consumption and forage and fodder for livestock consumption.

In the human environment, sustained economic growth, improved national security, and efficient and effective delivery of public services such as health and education are essential for improved livelihoods. Specific and appropriately formulated interventions through better public agriculture and nutrition policies are also necessary (Poole et al., Citation2018).

Agricultural innovation for seasonality and sustainability: The fundamental resilience and skills of the Afghan people are not in doubt. The development of the potato economy has had a dramatic impact on production systems and livelihoods. Such innovation is necessary, but the prevailing mono-cropping presents disease and market risks. Researchers in the natural sciences need to scan, explore and invest in potential food system innovations for improved nutrition (Glover & Poole, Citation2019; Shankar, Poole, & Bird, Citation2019). Varieties of grains and other rain-fed crops must be adapted to more erratic precipitation and higher temperatures (Obaidim et al., Citation2015). In the longer term, irrigated cropping patterns need to optimize water consumption as snowmelt becomes less reliable.

The cultural affinity to livestock, and the contribution of animal-sourced foods to combatting child stunting make sustainable livestock development a priority (Headey, Hirvonen, & Hoddinott, Citation2018). Alongside rangeland management and conservation, and besides alfalfa, more fodder crops are needed that are both productive in harsh conditions and can be stored to improve animal nutrition during the winter. Rangeland management is also necessary to conserve the wild plants for human consumption. Hence, domestication of rangeland wild plants is a potential area for future research and development {Poole, Citation2004, #1287}.

Production innovations must be accompanied by improved processing, marketing and value chain organization (Poole, Citation2018). Technologies for food processing and storage, together with protection for nutritious crops at the margins of the growing season can reduce the period of micronutrient insufficiency.

Vegetables and fruits help to combat common micronutrient deficiencies. Protected production of vegetables is already used on a small scale. A recent project has demonstrated the feasibility of combining agricultural training and input support to adolescent girls in the provinces of Kabul, Parwan and Kapisa. This also highlights the value of multi-sectoral interventions linking horticulture, gender, education and nutrition (Alim & Hossain, Citation2018).

Watermelon is already an important seasonal crop. Cucurbitaceae offer both culinary variety and nutritional value to diets as potentially rich sources of micronutrients including β-carotene, the vitamin A precursor. They can be stored and may serve to buffer consumption into the lean season. Expansion and diversification of fruit tree production and agro-forestry likewise could reduce vulnerability to seasonality and shocks.

The production, nutrition and storage characteristics of pulses suggest that dietary and economic improvements and better risk management generally could be derived from a wider agricultural production diversity, as recommended elsewhere (Nicklin, Rivera, & Nelson, Citation2006). Grass pea (Lathyrus sativus) is an underexploited legume in the Hindu Kush, other parts of Asia and in Africa for humans and livestock for subsistence and surplus generation and, in adverse conditions, for insurance and survival (Dixit, Parihar, Bohra, & Singh, Citation2016). Grass pea requires very low inputs and can be a key element of sustainable agricultural systems in harsh environments. Its value will increase under the likely adverse conditions of climate change. The disadvantage of grass pea is a neurotoxin causing lathyrism. Nevertheless, new varieties can be developed from low-toxin genetic stocks (Vaz Patto & Rubiales, Citation2014).

Local innovations: A penultimate comment is that technical solutions have to be sought for local conditions. Therefore the current reliance on a single ‘innovation’ such as the potato economy is both undesirable and infeasible for a number of reasons. Linking sectors like agriculture, livestock and forestry, building on local skills, is essential for adaptation to climate change (Leakey, Tchoundjeu, Schreckenberg, Shackleton, & Shackleton, Citation2005; Meijer, Catacutan, Ajayi, Sileshi, & Nieuwenhuis, Citation2014). Territorial and climate-sensitive innovation is needed, and must not be conditioned by the ‘requirement’ for pan-territorial upscaling, which is unlikely to address the specificities of local conditions (Poole, Citation2017).

Integrated and multi-sectoral approaches: When Afghanistan becomes more stable and prosperous, public investment is required for infrastructure, energy and communications technologies that will permit the development of viable local agribusiness and markets, and integrated delivery of development services (Donovan, Blare, & Poole, Citation2017; Gillebo & Hugo, Citation2006). Recent LANSA research has highlighted the importance of understanding the drivers of the enabling environment for improving the agri-nutrition environment (Gillespie et al., Citation2019). Seasonality is hugely significant here for food production and consumption, but also for the operation of other markets and driving factors. A systematic and multi-sectoral approach to agriculture and nutrition is needed to complement locale-specific initiatives. There needs to be a range of indicators that embrace the natural and social environments, including the gender issues in production, markets and consumption (Poole, Citation2018). Currently, policy coherence in Afghanistan is weak (Poole et al., Citation2018), and nutrition is not prioritized. Above all, political solutions to the prevailing national insecurity will enable sustainable improvement to be made in nutrition-sensitive agricultural development.

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of the research generated by the Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in South Asia (LANSA) research consortium, and is funded by UK aid from the UK government. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies. Authors wish to acknowledge the support of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in Afghanistan who facilitated many aspects of the research, and particularly the contribution of Ms Aoife Franklyn who was also involved in the design and execution of the empirical work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Nigel Poole is Professor of International Development at CeDEP, SOAS University of London and led the Afghan work of the DFID Research Consortium ‘Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in South Asia’ (LANSA).

Habiba Amiri, Sardar Muhammad Amiri and Islamudin Farhank lead the Ecology and Conservation Organization of Afghanistan, based in Bamyan, Afghanistan.

Giacomo Zanello is Associate Professor in Food Economics and Health at the University of Reading, UK.

ORCID

Nigel Poole http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2157-7883

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. These nil responses may have been a data collection omission.

2. See Fitzherbert (Citation2014).

References

- Ahmed, N., Brzozowski, M., & Crossley, T. F. (2006). Measurement errors in recall food consumption data, WP06/21. Institute for Fiscal Studies. Retrieved from https://www.ifs.org.uk/wps/wp0621.pdf

- Akseer, N., Bhatti, Z., Mashal, T., Soofi, S., Moineddin, R., Black, R. E., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2018). Geospatial inequalities and determinants of nutritional status among women and children in Afghanistan: An observational study. The Lancet Global Health, 6(4), e447–e459. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30025-1

- Alim, M. A., & Hossain, M. A. (2018). Nutrition promotion and collective vegetable gardening by adolescent girls: Feasibility assessment from a pilot in Afghanistan. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development, 8(1), 40–49. doi: 10.18488/journal.1005/2018.8.1/1005.1.40.49

- Berney, L. R., & Blane, D. B. (1997). Collecting retrospective data: Accuracy of recall after 50 years judged against historical records. Social Science & Medicine, 45(10), 1519–1525. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00088-9

- Brzozowski, M., Crossley, T. F., & Winter, J. K. (2017). A comparison of recall and diary food expenditure data. Food Policy, 72, 53–61. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.08.012

- Carney, D. (Ed.). (1998). Sustainable livelihoods: What contribution can we make? London: Department for International Development (DFID).

- CDC. (2018). International micronutrient malnutrition prevention and control (IMMPaCt): Micronutrient facts. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), US Department of Health & Human Services.

- Chambers, R., & Conway, G. R. (1992). Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century ( IDS discussion paper no 296). Brighton: IDS.

- CSO. (2014). National risk and vulnerability assessment 2011–2012 (Afghanistan living conditions survey). Kabul: Central Statistics Organization (CSO), Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.

- CSO. (2016). Afghanistan living conditions survey 2013–2014. National risk and vulnerability ASSESSMENT. Kabul: Central Statistics Organization (CSO), Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Retrieved from http://cso.gov.af/Content/files/ALCS/ALCS%20ENGLISH%20REPORT%202014.pdf

- CSO. (2018). Afghanistan living conditions survey 2016–2017. Analysis report. Kabul: Central Statistics Organization (CSO), Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Retrieved from http://cso.gov.af/Content/files/ALCS/ALCS%202016-17%20Analysis%20report%20-%20Full%20report23%20_09%202018-ilovepdf-compressed.pdf

- Dixit, G. P., Parihar, A. K., Bohra, A., & Singh, N. P. (2016). Achievements and prospects of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) improvement for sustainable food production. The Crop Journal, 4(5), 407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2016.06.008

- Donovan, J., Blare, T., & Poole, N. (2017). Stuck in a rut: emerging cocoa cooperatives in Peru and the factors that influence their performance. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 15(2), 169–184. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2017.1286831

- Donovan, J., & Poole, N. D. (2013). Asset building in response to value chain development: Lessons from taro producers in Nicaragua. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 11(1), 23–37. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2012.673076

- Donovan, J., Poole, N., Poe, K., & Herrera-Arauz, I. (2018). Ambition meets reality: Lessons from the taro boom in Nicaragua. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 8(1), 77–98. doi: 10.1108/JADEE-02-2017-0023

- Dorward, A., Poole, N. D., Morrison, J. M., Kydd, J. K., & Urey, I. (2003). Markets, institutions and technology: Missing links in livelihoods analysis. Development Policy Review, 21(3), 319–332. doi: 10.1111/1467-7679.00213

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. (2018). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2018. Building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. Rome: FAO. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/I9553EN/i9553en.pdf

- Fitzherbert, A. (2014). An introductory guide to sources of traditional fodder and forage and usage: Environmental resilience in pastoral systems in Afghanistan. Kabul: United Nations Environment Programme.

- Flores-Martínez, A., Zanello, G., Shankar, B., & Poole, N. (2016). Reducing anemia prevalence in Afghanistan: Socioeconomic correlates and the particular role of agricultural assets. PLoS One, 11(6), e0156878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156878

- Gillebo, T., & Hugo, A. (2006). Sustainable entrepreneurship: Regional innovation cultures in the ecological food sector. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 4(3), 244–256. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2006.9684805

- Gillespie, S., Poole, N., van den Bold, M., Bhavani, R. V., Dangour, A., & Shetty, P. (2019). Leveraging agriculture for nutrition in South Asia: What do we know, and what have we learned? Food Policy, 82, 3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.10.012

- Glover, D., & Poole, N. (2019). Principles of innovation to build nutrition-sensitive food systems in South Asia. Food Policy, 82, 63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.10.010

- GoIRA. (2012). Afghanistan food security and nutrition agenda (AFSANA). A policy and strategic framework. Kabul: Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GoIRA).

- Headey, D., Hirvonen, K., & Hoddinott, J. (2018). Animal sourced foods and child stunting. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100(5), 1302–1319. doi: 10.1093/ajae/aay053

- Himaz, R. (2018). Stunting later in childhood and outcomes as a young adult: Evidence from India. World Development, 104, 344–357. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.019

- IFPRI. (2016). Global nutrition report 2016. From promise to impact: Ending malnutrition by 2030. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. Retrieved from http://www.ifpri.org/publication/global-nutrition-report-2016-promise-impact-ending-malnutrition-2030

- Jones, A. D. (2017). Critical review of the emerging research evidence on agricultural biodiversity, diet diversity, and nutritional status in low- and middle-income countries. Nutrition Reviews, 75(10), 769–782. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux040

- Jones, A. D., Shrinivas, A., & Bezner-Kerr, R. (2014). Farm production diversity is associated with greater household dietary diversity in Malawi: Findings from nationally representative data. Food Policy, 46, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.02.001

- Leakey, R. R. B., Tchoundjeu, Z., Schreckenberg, K., Shackleton, S. E., & Shackleton, C. M. (2005). Agroforestry tree products (AFTPs): Targeting poverty reduction and enhanced livelihoods. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 3(1), 1–23. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2005.9684741

- Lloyd, S. J., Bangalore, M., Chalabi, Z., Kovats, R. S., Hallegatte, S., Rozenberg, J., … Havlík, P. (2018). A global-level model of the potential impacts of climate change on child stunting via income and food price in 2030. Environmental Health Perspectives, 126(9), 097007. doi: 10.1289/EHP2916

- MAIL. (2016). National comprehensive agriculture development priority program 2016–2020. Final draft. Kabul: Government of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock (MAIL). Retrieved from http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/afg167994.pdf

- Masset, E., Haddad, L., Cornelius, A., & Isaza-Castro, J. (2012). Effectiveness of agricultural interventions that aim to improve nutritional status of children: Systematic review. British Medical Journal, 344, d8222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d8222

- Meijer, S. S., Catacutan, D., Ajayi, O. C., Sileshi, G. W., & Nieuwenhuis, M. (2014). The role of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions in the uptake of agricultural and agroforestry innovations among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 13(1), 40–54. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2014.912493

- Miller, V., Yusuf, S., Chow, C. K., Dehghan, M., Corsi, D. J., Lock, K., … Mente, A. (2016). Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: Findings from the prospective urban rural epidemiology (PURE) study. The Lancet Global Health, 4(10), e695–e703. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30186-3

- Nicklin, C., Rivera, M., & Nelson, R. (2006). Realizing the potential of an Andean legume: Roles of market-led and research-led innovations. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 4(1), 61–78. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2006.9686012

- Obaidim, M. Q., Azmatyar, M. H., Mohmand, E., Habibi, A., Qayum, A., & Sharma, R. (2015). Lalmi 04 – A new rainfed wheat variety for Afghanistan. Triticeae Genomics and Genetics, 6(1), 1–3. doi: 10.5376/tgg.2015.06.0001

- OCHA. (2018). Afghanistan weekly field report | 28 May–3 June 2018. Kabul: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Retrieved from https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/20180603_afghanistan_weekly_field_report_28_may_-_3_june_2018.pdf

- Pellegrini, L., & Tasciotti, L. (2014). Crop diversification, dietary diversity and agricultural income: Empirical evidence from eight developing countries. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 35(2), 211–227. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2014.898580

- Pingali, P. (2015). Agricultural policy and nutrition outcomes – Getting beyond the preoccupation with staple grains. Food Security, 7(3), 583–591. doi: 10.1007/s12571-015-0461-x

- Poole, N. (2004). Perennialism and poverty reduction: Knowledge strategies for tree and forest products. Development Policy Review, 22(1), 49–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8659.2004.00238.x

- Poole, N. (2017). Smallholder agriculture and market participation. Rugby: Practical Action and United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. doi: 10.3362/9781780449401.000-011

- Poole, N. (2018). Building dairy value chains in Badakhshan, Afghanistan. IDS Bulletin, 49(1), 107–127. doi: 10.19088/1968-2018.107

- Poole, N., Echavez, C., & Rowland, D. (2018). Are agriculture and nutrition policies and practice coherent? Stakeholder evidence from Afghanistan. Food Security, 10(6), 1577–1601. doi: 10.1007/s12571-018-0851-y

- potatopro.com. (2017, November 12). Potato production in Bamyan, Afghanistan increases 15 percent to 350,000 tonnes this year. Retrieved from https://www.potatopro.com/news/2017/potato-production-bamyan-afghanistan-increases-15-percent-350000-tonnes-year

- Powell, B., Thilsted, S. H., Ickowitz, A., Termote, C., Sunderland, T. C. H., & Herforth, A. (2015). Improving diets with wild and cultivated biodiversity from across the landscape. Food Security, 7(3), 535–554. doi: 10.1007/s12571-015-0466-5

- Ritchie, H., & Fitzherbert, A. (2008). The white gold of Bamyan. A comprehensive examination of the Bamyan potato value chain from production to consumption. Clichy-La-Garenne: Solidarités.

- Ritzema, R. S., Frelat, R., Douxchamps, S., Silvestri, S., Rufino, M. C., Herrero, M., … van Wijk, M. T. (2017). Is production intensification likely to make farm households food-adequate? A simple food availability analysis across smallholder farming systems from East and West Africa. Food Security, 9(1), 115–131. doi: 10.1007/s12571-016-0638-y

- Savo, V., Lepofsky, D., Benner, J. P., Kohfeld, K. E., Bailey, J., & Lertzman, K. (2016). Observations of climate change among subsistence-oriented communities around the world. Nature Climate Change, 6(5), 462–473. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2958

- Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1), 171–196. doi: 10.1080/03066150902820503

- Shankar, B., Poole, N., & Bird, F. A. (2019). Agricultural inputs and nutrition in South Asia. Food Policy, 82, 28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.10.011

- Sibhatu, K. T., Krishna, V. V., & Qaim, M. (2015). Production diversity and dietary diversity in smallholder farm households. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(34), 10657–10662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510982112

- Sibhatu, K. T., & Qaim, M. (2017). Rural food security, subsistence agriculture, and seasonality. PLoS One, 12(10), e0186406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186406

- Sununtnasuk, C., & Fiedler, J. L. (2017). Can household-based food consumption surveys be used to make inferences about nutrient intakes and inadequacies? A Bangladesh case study. Food Policy, 72, 121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.08.018

- UNEP. (2017). Shah Foladi declared Afghanistan’s newest protected area. Kabul: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Retrieved from https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/shah-foladi-declared-afghanistans-newest-protected-area

- UNICEF. (2014). National nutrition survey: Afghanistan (2013). Kabul: United Nations Children's Fund. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Report%20NNS%20Afghanistan%202013%20%28July%2026-14%29.pdf

- Vaz Patto, M. C., & Rubiales, D. (2014). Lathyrus diversity: Available resources with relevance to crop improvement – L. sativus and L. cicera as case studies. Annals of Botany, 113(6), 895–908. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu024

- World Food Programme. (2008). Food consumption analysis. Calculation and use of the food consumption score in food security analysis. Rome: World Food Programme, Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping Branch (ODAV). Retrieved from https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/manual_guide_proced/wfp197216.pdf?_ga=2.1262641.1849853196.1533301306-1061029227.1533301306

- Zanello, G., Shankar, B., & Poole, N. (2019). Buy or make? Agricultural production diversity, markets, and dietary diversity in Afghanistan. Food Policy. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2019.101731

- Zezza, A., Carletto, C., Fiedler, J. L., Gennari, P., & Jolliffe, D. (2017). Food counts. Measuring food consumption and expenditures in household consumption and expenditure surveys (HCES). Introduction to the special issue. Food Policy, 72, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.08.007