ABSTRACT

Complexity of African agrarian systems necessitates that agricultural research and development transition to agricultural innovation system [AIS] approaches. While AIS perspectives are embraced across sub-Saharan Africa, engagement of stakeholders in agricultural research and development processes as espoused in AIS paradigm remains limited. This paper aims to analyze key stakeholders in the AIS in Malawi using the case of Conservation Agriculture [CA]. We analyze roles, organizational capacity and collaboration of stakeholders in Malawi’s CA innovation system. Although Government has the most extensive role, NGOs dominate the national CA agenda, while smallholder farmers remain passive recipients of CA interventions. Many CA promoters lack technical and financial capacity, and pursue limited collaboration, which diminish prospects of inclusive stakeholder engagement. While insufficient resources lead to inadequate technical support to smallholders, the limited collaboration hinders integration of programmes, multiple sources of innovation and knowledge required to foster social learning and sustainability of CA. Our findings indicate a need to: (1) strengthen understanding of AIS approaches among CA innovation system stakeholders; (2) build stronger partnerships in CA research and development by strengthening stakeholder platforms and social processes; (3) strengthen collaboration advisory mechanisms to facilitate knowledge-sharing, resource mobilization and joint programme implementation with strengthened feedback loops.

1. Introduction

A growing body of literature agrees that development-oriented multi-stakeholder processes need to be carefully designed if social learning and long-lasting impact are to be achieved (Leventon et al., Citation2016; Pretty, Citation1995). This requires early identification and engagement of stakeholders which creates space for them to influence the process from inception (Dougill et al., Citation2006). Early identification and engagement is critical for meaningful information exchange and interaction in problem definition, design, implementation and sustainability (Dyer et al., Citation2014; Pretty, Citation1995). However, various authors illustrate that identifying stakeholders particularly in developing-country contexts is a challenging task. For instance, while certain stakeholder categories may be historically marginalized and difficult to identify, others simply involve a pre-selected group of vocal stakeholders, already engaged in related interventions (Daniels & Walker, Citation2001). Further, pre-existing conflicts between different stakeholder groups can preclude a willingness to join a deliberative process (Grimble & Wellard, Citation1997). As participatory processes tend to focus on small groups for in-depth deliberation and mutual learning, lack of representativeness becomes the norm (Stringer et al., Citation2006) which may intensify existing conflicts and thereby undermine trust and sustainability efforts from the outset.

A stakeholder is any individual, organization or group that affects, or can be affected by a decision, action or outcome (Reed et al., Citation2014). Stakeholders may hold hidden or explicit interests in an issue and act at different scales (Prell et al., Citation2009). Interests held by stakeholders may be physical, economic or jurisdictional (Leventon et al., Citation2014). Stakeholders are mainly engaged for three reasons: (1) normative, to represent a democratic ideal by focussing on the process of inclusion; (2) substantive, to harness knowledge and risk perceptions from stakeholders to improve outcomes; and (3) instrumental, to enhance legitimacy of pre-defined decisions (Fiorino, Citation1990). It is thus imperative to understand the stakeholder environment prior to undertaking any form of research and development so as to consider whom to include, why and how that impacts upon achieving the purpose (Leventon et al., Citation2016).

When considering ‘who’ to include, Pohl et al. (Citation2010) stress that including only ‘experts’ closes down the participation space, narrows the discourse and undermines sustainability efforts. Conversely, opening up the participation space to include non-experts (particularly local community input) broadens the discourse, a precondition for appraising decisions and shaping agendas (Stirling, Citation2008). Having an open space for participation enables negotiation besides generating a robust common knowledge base as it seeks perspectives from different sources, which according to Roling and Wagemakers (Citation1998) minimises risk and uncertainty. Genuine inclusion of both experts and non-experts is said to result in better results and sustainability as their active involvement provides insight into social, ethical and political contexts which offer legitimacy to the research-development process (Stringer et al., Citation2006). Key to opening up the participation space is to include stakeholders with diverse views, capacities and interests so that a wide range of ideas and solutions are formulated and discussed to create a common vision (Prell et al., Citation2009). The extent to which key stakeholders influence the decision-making process determines the extent to which knowledge generated is accessed, shared and utilized (Reed et al., Citation2014). Knowledge can only inform policy and practice if it is relevant, legitimate and accessible; and secured through participatory multi-stakeholder processes.

The UN FAO (Citation2017) defines Conservation Agriculture [CA] as a set of agricultural principles and practices mainly aimed at improving food security and incomes whilst conserving land and water resources. CA is anchored on 3 principles (minimum soil disturbance, continuous soil cover and crop association) which have to be concurrently applied to achieve resilience benefits. Viewed as a promising sustainable agricultural intensification strategy for Malawi (Rodenburg et al., Citation2020), development agencies have invested in CA promotion for over 15 years (Ngwira et al., Citation2014). Despite purported benefits of CA (see Kassam et al., Citation2019), impact of CA interventions has been less than convincing among smallholder farmers (Andersson & Giller, Citation2019; Bouwman et al., Citation2021). Various authors have drawn attention to CA’s complexity (Corbeels et al., Citation2014), knowledge intensity (Hermans et al., Citation2020; Ndah et al., Citation2015) and the need for greater scrutiny of processes in CA promotion (Chinseu et al., Citation2019b). However, a comprehensive examination of stakeholders in the CA innovation system is still lacking in the Malawian context. A critique of Malawi’s CA innovation system will yield useful knowledge for informing agricultural development interventions more broadly across the sub-Saharan African region, bearing in mind its heavy reliance on rain-fed cultivation systems (Ngwira et al., Citation2014). Detailed knowledge about CA stakeholders is important for informing decisions about whom to involve in future CA research and development processes, dialogue and interventions to ensure inclusive design and implementation for optimal project outcomes (Dougill et al., Citation2017). According to Dyer et al. (Citation2014), stakeholder knowledge can help establish the most effective and efficient way (tailored to the context, stakeholder category and level of engagement), to gain support and involvement of key individuals and organizations in the innovation system.

This article addresses three main objectives. It will: (1) identify and characterize relevant stakeholders in Malawi’s CA innovation system; (2) analyze the organizational capacity of prominent stakeholders in the innovation system; (3) analyze collaboration of selected CA stakeholders and their connections between national, district and local levels of governance. Our findings highlight critical leverage points for enhancing knowledge co-generation, resource sharing and multi-stakeholder engagement to strengthen the CA innovation system and thus enhance CA’s potential to achieve lasting impact and sustainability.

1.1 Theoretical framework

This study has been informed by the Agricultural Innovation System (Spielman & Birner, Citation2008) theory. An Agricultural Innovation System [AIS] is a network of individuals, enterprises and/or organizations together with supporting institutions and policies in agriculture and related sectors that bring existing or new products, processes and forms of organization into economic and social use (Aerni et al., Citation2015). AIS theory consists of three main interconnected clusters namely: (1) agricultural research and education systems; (2) bridging institutions; and (3) agricultural value chain actors and organizations (Spielman & Birner, Citation2008). The AIS approach can engage different actors (e.g. policy, economic, science, technology and international actors) in an interactive and dynamic fashion, all contributing to the production, processing or value-addition, distribution and marketing of agricultural goods and services (Ndah et al., Citation2014).

The AIS framework supersedes the national research system and the agricultural knowledge and information system frameworks that informed agricultural research and development in developing countries during the 1980s and 1990s (Kaluzi et al., Citation2017). The AIS framework is particularly intended to address the problem of linearity inherent in the previous national research system and the agricultural knowledge and information system approaches (Anandajayasekeram, Citation2011). The AIS poses a significant paradigm shift from earlier approaches with its emphasis that agricultural innovations need not only originate from designated national research institutions, but also from local innovation system actors including smallholder farmers. The AIS transcends researchers, farmers and extension providers and encompasses local innovation, public-private partnerships and participatory rural approaches within specific political, institutional and social contexts (Future Agricultures Consortium CAADP, Citation2012). As the AIS is a systems-oriented approach, it seeks to integrate multiple sources of knowledge, innovation, and puts emphasis on interactive learning to enable knowledge co-generation and sharing. Further, the AIS recognizes processes of institutional change and multi-directional interactions in the generation, dissemination and utilization of technologies (Spielman & Birner, Citation2008; World Bank, Citation2012).

AIS has been widely applied in agricultural research and development, such as (1) guiding the identification of relevant stakeholders, policies or institutions within the agricultural system (e.g. Chinseu et al., Citation2018; Kaluzi et al., Citation2017); (2) guiding the diagnosis of components in the innovation system to determine those that are lacking or in need of improving (e.g. Dougill et al., Citation2017; Gunter et al., Citation2017) and; (3) examining structures, operations and processes that govern the relevant agricultural systems (e.g. Corbeels et al., Citation2014; Hermans et al., Citation2020; Ndah et al., Citation2014).

2. Methodological approach

2.1 Study area

Malawi provides an appropriate case for this study because: (1) economic performance of the country and people’s livelihoods are directly linked to performance of the agricultural sector (2) intensive promotion of CA is used as a strategy for addressing various climatic, production and social-economic challenges currently affecting the country; (3) of the need for Malawi to effectively transition from the traditional transfer of technology to an innovation systems approach and enhance knowledge co-generation and exchange amongst CA stakeholders for sustainable agricultural transformation to occur (see Chinseu et al., Citation2019a; Future Agricultures Consortium CAADP, Citation2012; Mwase et al., Citation2014).

In Malawi, CA has been strongly influenced by the Sasakawa Global 2000 programme, which is widely credited for pioneering active promotion of the concept of CA to small scale farmers in Malawi (Dougill et al., Citation2017). Sasakawa Global 2000 introduced CA to the country following an international workshop in Zimbabwe in 1998 on ‘Conservation Tillage for Sustainable Agriculture’ (Ngwira et al., Citation2014). The Sasakawa CA programme, jointly implemented nationwide with the Government’s Ministry of Agriculture, aimed at improving soil fertility, yields and reduce labour requirements. However, promotion of CA produced limited success, which eventually resulted in stalling of the programme by the turn of the new millennium. Enthusiasm in CA was revived in 2002 following the launch of Southern Africa’s CA regional working group. With support from the UN FAO, countries in the region were required to establish national CA coordinating bodies (Dougill et al., Citation2017); which led to the formation of Malawi’s nationwide stakeholder platform - the National Conservation Agriculture Task Force [NCATF] (NCATF, Citation2016). The NCATF (now registered as Sustainable Agriculture Trust) remains operational with a mission to galvanize, support and scale-up evidence-based sustainable agricultural practices in a coordinated manner by advocating for technical and policy interventions that do not degrade productive capacity of land-based resources in Malawi.

2.2 Methods

We used key informant interviews (Bryman, Citation2016) together with document analysis (Scott, Citation1990) to accomplish a comprehensive analysis of stakeholders across Malawi’s CA innovation system. The AIS framework (Spielman & Birner, Citation2008) guided the process of developing initial focal areas and identifying stakeholders. To identify stakeholders for interview, we obtained an inventory comprising CA stakeholders from the then National Conservation Agriculture Task Force, a coordinating platform of CA in the country (Ngwira et al., Citation2014). From that list, we purposively selected prominent CA stakeholders in collaboration with the Department of Land Resources and Conservation in the Ministry of Agriculture (being the host Department for CA in Malawi). We used purposive sampling (Hay, Citation2010) to target key informants with first-hand knowledge and/or experience in CA implementation, agricultural research and education, extension delivery (bridging institutions), policy-formulation process, funding and agricultural value addition. We used snowball sampling (Bryman, Citation2016) to select key informants between and within groups of stakeholders. 52 interviews were conducted, guided by the following themes: role in CA, CA knowledge and attitude, stakeholder interactions and constraints. Sample size was determined by means of saturation (Hay, Citation2010). Additionally, we conducted 10 in-depth interviews with key informants from NGO and Government stakeholder categories (being prominent CA promoters in the country) to get insight into their organizational structure, technical and financial capacity and collaboration processes. The nature of the interviews enabled further probing to get more details or insight from key informants (Hay, Citation2010). Though English is the official language for conducting business in Malawi, some key informants mixed both English and Chichewa. The Chichewa language was being used particularly when expressing their in-depth opinions or when emphasizing or clarifying a point. Interview data was transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis (Bryman, Citation2016). Anonymity of key informants and their organizations is maintained for ethical reasons.

Documentary materials for analysis () were identified purposively based on their usefulness and relevance to the research aims (Baxter & Eyles, Citation1997) and ‘richness of textual detail’ (Waitt, Citation2010). Analysis of the documents was accomplished using thematic content analysis (Kalaba et al., Citation2014) to obtain secondary data on CA implementation activities, funding, stakeholder collaboration, coordination and synergy of programmes. The secondary data sources were also used for triangulation purposes.

Table 1. Secondary data sources selected for documentary analysis.

3. Results

3.1 Identification and characterization of stakeholders in the CA innovation system

Data revealed a diverse array of stakeholders involved in the CA innovation system in Malawi. Eight main categories of stakeholders were identified according to their key roles in CA ().

Table 2. Main CA stakeholder categories and their roles in Malawi’s CA innovation system.

Although Government has the most extensive role in the CA innovation system (), NGOs dominate the national CA agenda in Malawi. Conversely, smallholder farmers were largely described as passive recipients of technical advice and mere implementers of CA, with little or no involvement in CA research and policy decision-making. This depicts a typically one-way linear type of stakeholder interaction, not in keeping with AIS principles.

Data from 10 prominent CA promoting organizations revealed three prominent features of CA promoters: motivation for promoting CA was comparable; international donors were the major sources of funding for CA interventions; and with the exception of the Malawi Government, most promoters had limited geographical coverage and used temporary implementation structures in disseminating CA ().

Table 3. Features of prominent CA stakeholders in Malawi.

Although the Malawi Government through the Ministry of Agriculture has nationwide geographic coverage with permanent implementation structures (), not all relevant Departments are involved in CA. The data only showed three Government Departments in the Ministry as having a role in CA: the Department of Land Resources and Conservation, Department of Agricultural Extension Services and the Department of Agricultural Research Services. Contrary to innovation systems approach requirements on stakeholder involvement (Aerni et al., Citation2015), relevant CA Departments such as Department of Crop Production, Department of Animal Health and Livestock Development and Department of Irrigation Services played no role in CA and had not integrated it in their programme activities. This raised the possibility of devising approaches and messages that conflict with CA across different Departments without proper coordination.

The common distinct features of NGOs were temporary implementation structures and localised nature of their geographic coverage. While some operated within one district, others had the mandate to operate in selected districts across the three regions of the country: ‘The way we operate normally is that, depending on project guidelines, when that project phases out, we move from one area to another’ (NGO Manager). Having such temporary structures certainly makes CA unsustainable because once a CA project expires, it becomes challenging for smallholder farmers to continue practising CA independently in the absence of agricultural extension and farm input support hence dis-adoption becomes likely (Pedzisa et al., Citation2015).

3.2 Organizational capacity of CA promoters

Examination of the organizational capacity of Government and NGOs, as the major CA promoters in Malawi, revealed shortfalls in implementation structure, human resources and financial capacity.

3.2.1 Government implementation structure

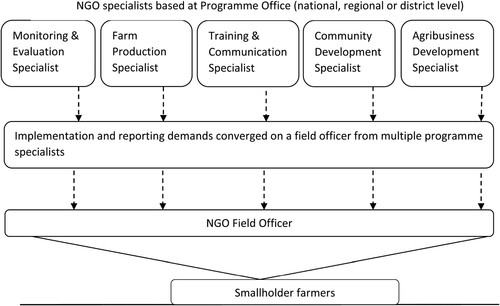

The Government, through the Ministry of Agriculture, has multiple technical specialists at top management levels but not at the frontline/grassroots level. From an extension service delivery perspective, the Ministry of Agriculture comprises six main technical Departments at three administrative levels: national (headquarters), Agricultural Development Division and district level. There are 8 Agricultural Development Divisions [ADDs] in Malawi, representing 8 agro-ecological zones nationwide. All agricultural extension-related services at district level (including CA activities) fall under the responsibility of the District Agricultural Development Office (totalling 28 district offices countrywide). Each district is geographically sub-divided into extension planning areas [EPA] (nationwide total of 203 EPAs). Each EPA is further sub-divided into sections consisting of 10–15 villages depending on population density. The total number of sections in Malawi was found to be 2746. Each section is managed by an Agricultural Extension Development Officer [AEDO] and is where extension and advisory services are delivered to smallholder farmers.

Comments from key informants reveal a lack of replication of the six technical Departments at the EPA level (), creating bottlenecks in extension service delivery to farmers.

Figure 1. Malawi Government agriculture implementation structure. Source: Interviews and policy documents.

Our study found that all subject matter specialists at the district level used the same frontline officer to implement their programmes: ‘I work with each and every subject matter specialist and I get overwhelmed when activities collide’ (AEDO). This structural shortfall concentrated multiple demands on a single AEDO at the section level, thus effectively turning AEDOs into ‘jack of all trades’ (extension generalists) implementing a diverse array of programmes. The use of extension generalists to execute ‘specialist’ activities arguably compromised the quality of extension service to CA farmers.

3.2.2 Typical NGO implementation structure

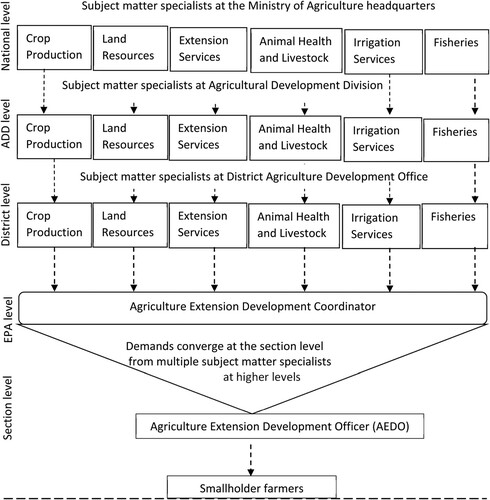

Structural set up for many NGOs tended to mimic the Government set-up. illustrates that extension demands from multiple programme specialists converged on one frontline field officer.

NGO frontline officers faced similar challenges to Government extension officers in their quest to meet targets of their programme specialists: ‘I have four project managers, all waiting for me to execute their programmes on the ground, it’s like a servant with four masters’ (NGO Frontline Officer). Frontline (field) officers were simultaneously implementing an array of programmes including CA: ‘Our field officers are involved in so many programmes; if he or she is not involved in CA activities, then he or she might be involved in community development or education or health activities or environment; it’s not about agriculture only’ (NGO Programme Manager). Like Government extension agents, NGO frontline officers were ‘generalists’ who simultaneously implemented a diversity of programmes, thus, the quality and intensity of extension support offered to farmers was potentially diminished.

3.2.3 Human and financial capacity of CA stakeholders

Inadequate extension personnel was consistently mentioned as a pressing challenge in CA implementation. We established that one extension worker was serving an average of 2688 farm families, contrary to Government’s recommendation of 500. Undoubtedly, extension visits to smallholder farms proved infrequent: ‘We only see our extension worker at planting time when he comes to deliver [chemical] fertilizer and seed for [CA] demos [demonstrations]’ (Lead farmer). As remote areas in Malawi tend to be sparsely populated, extension officers travelled long distances mostly on foot to find farmers ‘I have over 3000 farm families and every day, I have to walk almost 30 km in my section’ (Assistant Agricultural Extension Development Officer). Interview data hinted that low staffing levels overstretched frontline officers: ‘In my EPA, one AEDO [Agriculture Extension Development Officer] is now manning two or even three sections yet more and more programmes keep coming’ (Agricultural Extension Development Coordinator).

Though it is Government’s requirement that frontline extension officers possess a 2-year diploma in Agriculture or its equivalent from an accredited institution, 82% held a Malawi School Certificate of Education [MSCE], equivalent to General Certificate of Secondary Education. Though these extension officers are supposed to go for upgrading immediately after being recruited, it takes years for this to materialize due to financial constraints. This implies that most of the Government frontline extension personnel possess limited skills and knowledge in contemporary agricultural extension, which may negatively affect extension service delivery. Nonetheless, Government officials attributed the critical shortage of qualified extension officers to persistent poaching by non-state organizations: ‘NGOs are in the habit of poaching our highly experienced and qualified AEDOs [Agriculture Development Extension Officers] by enticing them’ (Department of Agriculture Extension Official). As Government vacancies generally take a long time to be filled (Nyanga, Citation2012), acute shortage of extension officers has the potential to cause long-term disruption of national (CA) programmes as many activities remain unaccomplished.

For NGOs, staffing levels tended to be top-heavy with no frontline extension personnel at the section level, where implementation of CA activities occurs. While Government extension officers are located at the section level, where interaction with farmers occurs, NGO field officers are positioned further away from farmers, either at their district programme office, area project office or Traditional Authority level, with one field officer overseeing an area equivalent to one or two Extension Planning Areas. An NGO extension officer hinted at the challenges emanating from this set up: ‘I have project sites in two EPAs because I have to establish more clubs to meet my target. I am always travelling from one site to another, supervising lead farmers’ (NGO Extension Officer). While locating the extension officer upstream allowed NGOs the ability to extend the project beneficiary catchment to a wider area, to increase chances of fulfilling expectations for increased numbers of project beneficiaries, such an arrangement increases travel time and reduces the amount of time spent advising farmers.

Interviews also reinforced the view that the major source of funding for CA activities in Malawi is international donors and funding agencies, notably: the African Development Bank, European Union, Irish Aid, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations [FAO], faith-based funding agencies, Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, UK Department for International Development, Japanese International Cooperation Agency, USAID, World Bank, Finland Ministry of Foreign Affairs, United Nations Development Programme and OXFAM. A sense of frustration with donor reliance was expressed by several interviewees: ‘Donors tend to fund particular areas that we feel are not urgent to us, but we cannot just transfer their money to the pressing areas since we have to strictly comply with their demands’ (High ranking Ministry Official). This suggests that donor interests may not always be in tandem with Government’s let alone farmers’ interests, implying that most of the donor-funded projects being implemented in the country are supply-driven, hence subject to sustainability issues (see Wood et al., Citation2016).

Though implementation of activities demands a regular and adequate flow of funds to effectively and efficiently accomplish an organization’s goal or objectives (Lowe et al., Citation1999), key informants in our study indicated that the funds they received were so insufficient that certain CA operations were constrained: ‘If we are failing to even purchase stationery for this office, what more with bicycles for AEDOs [Agriculture Development Extension Officers]?’ (District Extension Subject Matter Specialist). Apart from being unable to purchase motor cycles or bicycles, those with motor cycles claimed that they received insufficient fuel or waited long periods without receiving any. Some said they were unable to repair their motorcycles which rendered them unreliable. Insufficient funds also constrained many CA projects from expanding their beneficiary base: ‘We do not have enough money to give fertilizers and seed to all members in our clubs … the moment we stop giving them farm inputs, then they abandon CA altogether’ (NGO Project Officer). Apart from negatively affecting extension advisory service delivery, deficient financial resources evidently jeopardized sustainability of CA.

3.3 Collaboration of CA stakeholders

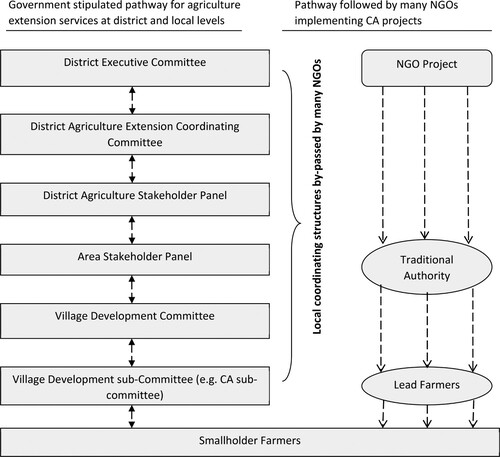

While the Malawi Government (Citation2006) stipulates that the entry point and pathway for all agricultural development and extension services delivery to communities is through the District Assembly (local government), to enhance coordination and synergy of extension service providers at the district and community levels, many NGOs by-passed the District Assembly agriculture coordinating structures when implementing their (CA) project activities ().

While numerous government informants expressed concern at the tendency of NGOs to by-pass local government coordinating structures, some NGO informants argued that they directly work with smallholder farmers ‘to avoid delays by Government bureaucracy’ (NGO Project Manager). NGOs’ sidelining of government staff appeared to erode the collaborative spirit as the state employees felt disrespected in their own ‘jurisdiction’: ‘These NGOs, they work with a lead farmer, not me, the owner of the section. Imagine, just one NGO has worked with us from project inception until now’ (Frontline Extension Officer). As a result, Government extension officers were generally less willing to take over expiring NGO projects, and CA activities often came to a halt upon project expiry (see also Chinseu et al., Citation2019b).

While senior NGO staff consistently indicated that they collaborated with other stakeholders in the promotion of CA, interviews with Government staff revealed little collaborative effort in practice on the ground: ‘These NGOs claiming collaboration, they are just using our AEDOs [frontline extension officers] behind our back, is that real collaboration?’ (District Subject Matter Specialist). Government interviewees described collaboration efforts of most NGOs as superficial, merely to fulfil their reporting requirement or feign solidarity with local structures with no real commitment: ‘What happens is that NGOs attend DEC [District Executive Committee] meetings just to show in their reports that they’re working with Government, but it will not be the Manager attending, it will be a very junior person who can’t make any decisions, let alone influence things in his organisation’ (District Agriculture Extension Coordinating Committee Official).

Collaboration was even limited among NGOs working in the same area, as organizations often viewed each other as competitors, contending for the same farmers. Some NGOs sought to work with others only when introducing a new project to take advantage of the existing knowledge and experience. Such collaborative efforts proved sporadic and short lived due to an absence of proper frameworks for continued engagement and knowledge sharing: ‘We initially worked together with [NGO Z] when they wanted to introduce CA to the community. They wanted our advice, because we have been implementing CA for some time. Then suddenly things changed, and we don’t interact anymore’ (NGO Extension Officer).

As CA stakeholders implemented diverse programmes other than CA, we found a widespread lack of integration of programmes funded by different donors within the same organization, contrary to AIS stipulations. For instance, programmes funded by the main international donor monopolized time and effort of field officers at the expense of other equally important activities: ‘This one project alone on nutrition, [X] being our main donor, occupies most of my time … for reporting, you complete so many forms, it’s too complicated. I am more concerned with completing [X] project activities than the rest’ (NGO Extension Officer). It transpired that although the nutrition project involved production and utilization of soy bean, CA was not incorporated just because it was funded by a different donor. As such, extension and advisory support for CA, which was a ‘non-priority’ and poorly funded, was insufficient, though it could have integrated well with the nutrition intervention.

Collaboration of CA-relevant Departments within the Ministry of Agriculture was also found to be limited especially between the Department of Agriculture Research Services [DARS], having a research mandate to generate or modify technologies, and the Department of Agriculture Extension Services, mandated to disseminate the developed/modified technologies to farmers. Apart from the limited inter-departmental collaboration in the Ministry, views from a cross section of key informants suggest ‘encroachment’ of responsibilities: ‘DARS scientists work in a silo [isolation], and they are now duplicating the role of technology dissemination which is our mandate’ (Department of Agriculture Extension Services Officer). A key informant from DARS explained: ‘We are now including a dissemination component in our research programmes to quickly popularise and scale-up adoption of the new technology’ (DARS Technology Transfer Officer). The limited collaboration persisting amongst the stakeholders, coupled with lack of sharing of information, knowledge and resources, potentially weakens the research-extension-farmer linkage, thereby stifling valuable contributions from farmers necessary for effective technology development/modification, sustainability and impact.

4. Discussion

Despite efforts by the Malawi Government to transform agricultural research and development toward AIS approaches, one-way linear tendencies persist in Malawi’s CA innovation system. Most notably, smallholders are only superficially engaged in CA research, development and policy-making decisions despite being the ultimate implementers of CA. While active engagement of relevant stakeholders is a prerequisite in innovation systems approaches (Aerni et al., Citation2015; Hessel et al., Citation2014), excluding such important stakeholders is likely to result in misalignment of CA interventions with smallholder farmers’ interests (Sousa et al., Citation2020).

Shortfalls in organizational capacity made extension services inadequate to support smallholders to implement CA successfully. For instance, limited financial resources restricted extension support to smallholders because mobility of extension officers was constrained due to lack of reliable motor cycles or fuel. Contrary to findings reported by Ragasa et al. (Citation2019), supervision of frontline extension officers by subject matter specialists was sporadic which diminished quality of technical messages delivered to farmers. The limited financial resources restricted efforts to recruit or (adequately) train extension officers, thus further weakening the extension delivery system (Mapila et al., Citation2010). These findings resonate with observations by other authors that the extension delivery system in Malawi suffers acute shortage of extension personnel. For example, Suarez et al. (Citation2008) reported that up to 48% of smallholder farmers in Malawi did not have access to extension advice for the entire 2008 crop growing season. As Government vacancies are slow to be filled (Nyanga, Citation2012), acute shortage of extension officers has the potential to cause long-term disruption of national (CA) programmes as many activities remain unaccomplished.

CA extension support was further undermined by extension officers serving a disproportionately high number of farm families. Evidence herein shows that one extension officer served up to 5 times the recommended number of farm families, concurring with findings by Ngwira et al. (Citation2014). Suarez et al. (Citation2008) argued that increasing the workload of extension officers increases work-related stress with subsequent reduced productivity. Consequently, extension officers fail to offer the required technical support to smallholders. On the other hand, poaching of best performing and qualified personnel is contrary to the pluralistic rationale of the existing agricultural extension policy as it stifles Government extension system. The issue of poaching was also observed by Nyanga (Citation2012) in Zambia where NGOs recruited competent Government extension officers which negatively affected farmers’ membership in Government CA projects, thus rendered counter-productive to the country’s CA agenda. As CA is a knowledge-intensive technology (Kaluzi et al., Citation2017), farmers need frequent and intensive support from extension agents which is generally unavailable due to resource limitations. Without adequate extension support, farmers have insufficient ‘how-to’ knowledge to successfully implement CA (Khataza et al., Citation2018; Ndah et al., Citation2014) hence CA projects become less sustainable (Chinseu et al., Citation2019a; Pedzisa et al., Citation2015). As such, shortfalls in organizational capacity of CA stakeholders jeopardise potential sustainability and prevent CA from having a greater impact among smallholder farmers.

In spite of the available local stakeholder platforms within the District Assembly, collaboration among CA promoters at the grassroots was found to be limited, contrary to AIS prerequisites. The AIS emphasizes collaboration among stakeholders to accomplish institutional learning, change and socioeconomic development (Aerni et al., Citation2015; Spielman, Citation2005). With a common tendency to by-pass stipulated District Agricultural Extension Coordinating structures, most NGOs failed to capitalize on stakeholder platforms that Government established for strengthening partnerships, sharing resources and field experiences for greater impact (Malawi Government, Citation2006). Apart from facilitating collective action, District Extension Coordinating structures enhance coherence in implementation of interventions which is necessary to garner support for CA projects, including assimilation of NGO CA projects into the Government system for continuity beyond project period. Due to ineffective collaboration, including lack of integration of CA with other programmes in the same organization, CA approaches and messages remain unharmonised, leading to dissemination of conflicting and confusing extension messages (Chinseu et al., Citation2018). Our study highlights the need to strengthen social interaction processes amongst CA stakeholders to stimulate participatory experiential learning and sharing of knowledge to effect sustained impact, particularly where shortfalls in extension capacity and resources prevail.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

This article has analyzed stakeholders in Malawi’s CA innovation system, examining their organizational capacity and collaboration. While the Government holds the most extensive role across the CA innovation system, NGOs drive the national CA agenda with support from international donor agencies. As such, CA promotion is largely defined by international donor interests, generally viewed to be mismatched with priorities of smallholder farmers or the Government. Consequently, smallholder farmers are not (adequately) involved in CA research and development processes despite being the ultimate implementers of CA.

Limited collaboration among CA stakeholders amidst perpetual deficiencies in organizational capacity (technical and financial capacity) diminishes prospects of an inclusive stakeholder engagement. The scenario propagates unfavourable conditions for knowledge co-production and sharing, being fundamental tenets of innovation systems. Whilst deterring multi-directional stakeholder interactions, the limited collaboration hinders integration of programmes, and multiple sources of innovation and knowledge required to foster social learning and sustainability of CA. It is imperative to: (1) strengthen understanding of AIS approaches among various stakeholders in agricultural research and development; (2) build stronger partnerships in CA research and development by strengthening stakeholder platforms and social processes, not only nationally, but also at district and local levels and the inter-connections across governance levels (); (3) establish collaboration advisory mechanisms to facilitate knowledge sharing, resource mobilization, joint programme implementation with strengthened feedback loops for continuous learning and sustainability; (4) use integrated landscape management approaches to facilitate greater CA integration into relevant state and non-state programmes and budgets.

While the stakeholder analysis was conducted in the context of the CA innovation system in Malawi, it could be usefully applied in similar farming systems across sub-Saharan Africa. The findings can inform improvements in the design and execution of agricultural research and development programmes and projects aimed at alleviating hunger, poverty and climate change impacts in agro-based economies across sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgements

The Commonwealth Scholarship Commission, United Kingdom provided financial support for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Edna L. Chinseu

Edna L. Chinseu is an expert in agriculture, environment and sustainability with a PhD in Earth and Environment from the University of Leeds. Her on-going work addresses sustainability issues of project-based development interventions in Malawian agricultural systems using social and natural science methods and theories.

Andrew J. Dougill

Andrew J. Dougill is a Professor of Environmental Sustainability at the University of Leeds. He has over 30 years of experience in leading the design and implementation of trans-disciplinary ‘solution-focused’ research projects focused on environmental sustainability and climate change at range of scales across southern Africa.

Lindsay C. Stringer

Lindsay C. Stringer is a Professor of Environment & Development at the University of York. Her research focuses on human-environment relationships, notably the links between livelihoods, environmental change and policy. She was a Lead Author on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on Climate Change and Land (2019) and for the IPCC’s 6th Assessment Report.

References

- Aerni, P., Nichterlein, K., Rudgard, S., & Sonnino, A. (2015). Making agricultural innovation systems (AIS) work for development in tropical countries. Sustainability, 7(1), 831–850. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su7010831

- Anandajayasekeram, P. (2011). The role of agricultural R&D within the agricultural innovation systems framework. Conference working paper 6. ASTI-IFPRI-FARA Conference. Accra: ASTI-IFPRI-FARA.

- Andersson, J. A., & Giller, K. E. (2019). Doing development-oriented agronomy: Rethinking methods, concepts and direction. Experimental Agriculture, 55(2), 157–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479719000024

- Baxter, J., & Eyles, J. (1997). Evaluating qualitative research in social geography: Establishing rigour in interview analysis. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 22 (4), 505–525. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-2754.1997.00505.x

- Bouwman, T. I., Andersson, J. A., & Giller, K. E. (2021). Adapting yet not adopting? Conservation Agriculture in Central Malawi. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 307, 107224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107224

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Chinseu, E., Dougill, A., & Stringer, L. (2019a). Why do smallholder farmers dis-adopt conservation agriculture? Insights from Malawi. Land Degradation & Development, 30(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3190

- Chinseu, E. L., Stringer, L. C., & Dougill, A. J. (2018). Policy integration and coherence for conservation agriculture initiatives in Malawi. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 7(4), 51–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/sar.v7n4p51

- Chinseu, E. L., Stringer, L. C., & Dougill, A. J. (2019b). An empirically derived conceptual framework to assess dis-adoption of conservation agriculture: Multiple drivers and institutional deficiencies. Journal of Sustainable Development, 12(5), 48–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v12n5p48

- Corbeels, M., de Graaf, J., Ndah, T. H., Penot, E., Baudron, F., Naudin, K., Andrieu, N., Chirat, G., Schuler, J., Nyagumbo, I., Rusinamhodzi, L., Traore, K., Mzoba, H. D., & Adolwa, I. S. (2014). Understanding the impact and adoption of conservation agriculture in Africa: A multi-scale analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 187, 155–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.10.011

- Daniels, S. E., & Walker, G. B. (2001). Working through environmental conflict: The collaborative learning approach. Praeger.

- Dougill, A. J., Fraser, E. D. G., Holden, J., Hubacek, K., Prell, C., Reed, M. S., Stagl, S., & Stringer, L. C. (2006). Learning from doing participatory rural research: Lessons from the Peak District National Park. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 57(2), 259–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2006.00051.x

- Dougill, A. J., Whitfield, S., Stringer, L. C., Vincent, K., Wood, B. T., Chinseu, E. L., Steward, P. R., & Mkwambisi, D. D. (2017). Mainstreaming conservation agriculture in Malawi: Knowledge gaps and institutional barriers. Journal of Environmental Management, 195, 25–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.09.076

- Dyer, J., Stringer, L. C., Dougill, A. J., Leventon, J., Nshimbi, M., Chama, F., Kafwifwi, A., Muledi, J. I., Kaumbu, J.-M. K., Falcao, M., Muhorro, S., Munyemba, F., Kalaba, G. M., & Syambungani, S. (2014). Assessing participatory practices in community-based natural resource management: Experiences in community engagement from southern Africa. Journal of Environmental Management, 137, 137–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.11.057

- Fao, U N. (2017). Climate-Smart Agriculture Sourcebook. http://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculturesourcebook/en/.

- Fiorino, D. J. (1990). Citizen participation and environmental risk: A survey of institutional mechanisms. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 15(2), 226–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/016224399001500204

- Future Agricultures Consortium CAADP. (2012). From technology transfer to innovation systems: Sustaining a green revolution in Africa. CAADP Policy Brief 07. Brighton: Future Agricultures CAADP. http://www.future-agricultures.org.

- Grimble, R., & Wellard, K. (1997). Stakeholder methodologies in natural resource management: A review of principles, contexts, experiences and opportunities. Agricultural Systems, 55(2), 173–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-521X(97)00006-1

- Gunter, J., Moore, K. M., Eubank, S., & Tino, G. (2017). Agricultural information networks and adoption of conservation agriculture in East Africa. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 24(1), 90–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5191/jiaee.2016.241109

- Hay, I. (2010). Qualitative research methods in human geography. Oxford University Press.

- Hermans, T., Whitfield, S., Dougill, A. J., & Thierfelder, C. (2020). Bridging the disciplinary gap in conservation agriculture research in Malawi. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 40(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-020-0608-9

- Hessel, R., Reed, M. S., Geeson, N., Ritsema, C. J., van Lynden, G., Karavitis, C. A., Schwilch, G., Jetten, V., Burger, P., van der Werff ten Bosch, M. J., Verzandvoort, S., van den Elsen, E., & Witsenburg, K. (2014). From framework to action: The DESIRE approach to combat desertification. Environmental Management, 54(5), 935–950. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-014-0346-3

- Kalaba, F. K., Quinn, C. H., & Dougill, A. J. (2014). Policy coherence and interplay between Zambia's forest, energy, agricultural and climate change policies and multilateral environmental agreements. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 14(4), 181–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-013-9236-z

- Kaluzi, L., Thierfelder, C., & Hopkins, D. W. (2017). Smallholder farmer innovation and contexts in maize-based conservation agriculture systems in Central Malawi. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 6(3), 85–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/sar.v6n3p85

- Kassam, A., Friedrich, T., & Derpsch, R. (2019). Global spread of conservation agriculture. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 76(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2018.1494927

- Khataza, R. B., Doole, G. J., Kragta, M. E., & Hailu, A. (2018). Information acquisition, learning and the adoption of conservation agriculture in Malawi: A discrete-time duration analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 132, 299–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.02.015

- Leventon, J., Fleskens, L., Claringbould, H., Frelih-Larsen, A., Schwilch, G., Bachmann, F., & Stringer, L. (2014). Report on stakeholder and institutional analysis. RECARE project report 02 D4.1. RECARE-University of Leeds.

- Leventon, J., Fleskens, L., Claringbould, H., Schwilch, G., & Hessel, R. (2016). An applied methodology for stakeholder identification in transdisciplinary research. Sustainability Science, 11(5), 763–775. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0385-1

- Lowe, P., Ward, N., & Potter, C. (1999). Attitudinal and institutional indicators for sustainable agriculture. In C. Brouwer (Ed.), Environmental indicators and agricultural policy (pp. 263–278). CABI.

- Malawi Government. (2006). The district agricultural extension services system: Implementation guide. Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security.

- Malawi Government. (2010). The agriculture sector wide approach (ASWAp): Malawi’s prioritised and harmonised agricultural development agenda. Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security.

- Malawi Government. (2016). National agriculture policy. Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development.

- Mapila, M., Makwenda, B., & Chitete, D. (2010). Elitism in the farmer organisation movement in post-colonial Malawi. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, 2(8), 144–153. https://academicjournals.org/article/article1380022285_Mapila%20et%20al.pdf

- Mwase, W., Jumbe, C., Gasc, F., Owiyo, T., Manduwa, D., Nyaika, J., Kwapata, K., & Maonga, B. (2014). Assessment of agricultural sector policies and climate change in Malawi- The nexus between climate change related policies, research and practice. Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(6), 195–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v7n6p195

- National Conservation Agriculture Task Force. (2016). Guidelines for implementing conservation agriculture in Malawi.

- Ndah, H. T., Schuler, J., Uthes, S., Zander, P., Traore, K., Gama, M., Nyagumbo, I., Triomphe, B., Sieber, S., & Corbeels, M. (2014). Adoption potential of conservation agriculture practices in sub-Saharan Africa: Results from five case studies. Environmental Management, 53(3), 620–635. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-013-0215-5

- Ndah, H. T., Schuler, J., Uthes, S., Zander, P., Triomphe, B., Mkomwa, S., & Corbeels, M. (2015). Adoption potential of conservation agriculture in Africa: A newly developed assessment approach (QAToCA) applied in Kenya and Tanzania. Land Degradation and Development, 26(2), 133–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2191

- Ngwira, A., Johnsen, F. H., Aune, J. B., Mekuria, M., & Thierfelder, C. (2014). Adoption and extent of conservation agriculture practices among smallholder farmers in Malawi. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 69(2), 107–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2489/jswc.69.2.107

- Nyanga, P. H. (2012). Factors influencing adoption and area under conservation agriculture: A mixed methods approach. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 1(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/sar.v1n2p27

- Pedzisa, T., Rugube, L., Winter-Nelson, A., Baylis, K., & Mazvimavi, K. (2015). Abandonment of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development, 8(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v8n1p69

- Pohl, C., Rist, S., Zimmermann, A., Fry, P., Gurung, G. S., Schneider, F., Speranza, C. I., Kiteme, B., Boillat, S., Serrano, E., Hadorn, G. H., & Wiesmann, U. (2010). Researchers’ roles in knowledge co-production: Experience from sustainability research in Kenya, Switzerland, Bolivia and Nepal. Science and Public Policy, 37(4), 267–281. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3152/030234210X496628

- Prell, C., Hubacek, K., & Reed, M. (2009). Stakeholder analysis and social network analysis in natural resource management. Society and Natural Resources, 22(6), 501–518. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920802199202

- Pretty, J. N. (1995). Participatory learning for sustainable agriculture. World Development, 23(8), 1247–1263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00046-F

- Ragasa, C., Mthinda, C., Chowa, C., Mzungu, D., Kalagho, K., & Kazembe, C. (2019). Assessing and strengthening Malawi’s pluralistic agricultural extension system: Evidence and lessons from a three-year research study. Project Note. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). http://www.ifpri.org/project/pluralistic-extension-system-malawi

- Reed, M. S., Stringer, L. C., Fazey, I., Evely, A. C., & Kruijsen, J. H. J. (2014). Five principles for the practice of knowledge exchange in environmental management. Journal of Environmental Management, 146, 337–345. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.021

- Rodenburg, J., Büchi, L., & Haggar, J. (2020). Adoption by adaptation: Moving from Conservation Agriculture to conservation practices. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1785734

- Roling, N. G., & Wagemakers, M. A. E. (1998). Facilitating sustainable agriculture: Participatory learning and adaptive management in times of environmental uncertainty. Cambridge University Press.

- Scott, J. (1990). A matter of record: Documentary sources in social research. Polity Press.

- Sousa, J., Rodrigues, P., & Basch, G. (2020). Social categories and agency within a conservation agriculture framework in Laikipia, Kenya. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 18(6), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1798179.

- Spielman, D. J. (2005). Innovation systems perspectives on developing-country agriculture: A critical review. ISNAR Discussion Paper 2. IFPRI.

- Spielman, J., & Birner, R. (2008). How innovative is your agriculture? Using innovation indicators and benchmarks to strengthen national agricultural innovation systems. World Bank.

- Stirling, A. (2008). “Opening up” and “closing down”: Power, participation, and pluralism in the social appraisal of technology. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 33(2), 262–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243907311265

- Stringer, L. C., Dougill, A. J., Fraser, E., Hubacek, K., Prell, C., & Reed, M. S. (2006). Unpacking “participation” in the adaptive management of social–ecological systems: A critical review. Ecology and Society, 11(2), 39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01896-110239

- Suarez, P., Givah, P., Storey, K., & Lotsch, A. (2008). HIV/AIDS, climate change and disaster management: Challenges for institutions in Malawi. Working Paper 4634. World Bank Policy Research.

- Waitt, G. (2010). Doing foucauldian discourse analysis-revealing social realities. In I. Hay (Ed.), Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography (pp. 217–240). Oxford University Press.

- Wood, B. T., Dougill, A. J., Quinn, C. H., & Stringer, L. C. (2016). Exploring power and procedural justice within climate compatible development project design: Whose priorities are being considered? Journal of Environment & Development, 25(4), 363–395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496516664179

- World Bank. (2012). Agricultural innovation systems: An investment sourcebook.