ABSTRACT

Sustainable agricultural intensification (SAI) practices have been developed with the aim of increasing agricultural productivity. However, most of them are not achieving their potential because of low adoption, linked to limited extension support to make them known and accessible by end-users. This paper reviews the effectiveness of the Africa Soil Health Consortium (ASHC) extension-based campaigns, contributing knowledge for formulating novel and cost-effective extension approaches. Results show that ASHC campaigns achieved scale of farmer reach and spurred adoption of promoted SAI technologies. Adoption levels for a range of practices were at least 20%, which favourably compares with reported adoption rates for the training and visit extension approach; 1-7% and 11-21% for complex and simple practices respectively. In comparison to a single channel, exposure to multiple communication approaches was associated with higher uptake of promoted practices and technologies, and also increased participation of men, women and youth, by addressing inherent differences in access to, proficiency with, and preferences of communication channels. Success factors associated with ASHC campaigns were; the deployment of multiple and complementary information channels; harnessing public-private partnerships to establish sustainable input supply chains; and development of localized content and fit-for-purpose information materials to facilitate information diffusion.

1. Background

The global population is projected to increase by 2 billion people, between 2019 and 2050 from 7.7 billion currently: 52% of those people will be added to the population of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and 25% to Central and South Asia (UN, Citation2019). To meet the food demand of the increasing global population, agricultural production and productivity must increase with minimal impacts on the environment (Wiebe, Citation2009). Sustainable agricultural intensification (SAI) has emerged with a generally accepted aim of increasing agricultural productivity while maintaining or improving environmental sustainability (Gunton et al., Citation2016). According to Thompson (Citation2008), intensification occurs when; (i) there is a higher productivity per unit of inputs leading to an increase in the total volume of agricultural production, or (ii) agricultural production is maintained while the use of certain inputs is decreased through better targeting, increased input use efficiency, and mixed or relay cropping on smallholder fields. Sustainable agricultural intensification practices include inputs and practices and the integration of technologies e.g. integrated soil fertility management (ISFM), soil and water conservation, conservation farming, legume intercropping and rotations, new crop varieties, integrated pest management and precision agriculture (Vanlauwe et al., Citation2010; Xie et al., Citation2019). Sustainable intensification enhances the productivity and resilience of agricultural production systems using a variety of specific measures in the agricultural production process while conserving the natural resource base (Kassie et al., Citation2015).

While various technologies (SAI practices) have been developed to achieve sustainable intensification, it is widely recognized that many of them are not achieving their full potential because of low adoption (Bentley et al., Citation2018). This limited adoption is in part attributed to limited agricultural support services to make practices and technologies known and accessible by end-users. There is a missing link to help quantify and communicate farmer demand to input-service suppliers to create buy-in for (pilot) deliveries or increased supply of the inputs-services. Other operational challenges include; insufficient funds for supporting the public extension, limited involvement of rural farmers and populations in extension processes, lack of appropriate extension methods, and challenges in adapting technology packages to community-specific contexts (IFPRI – World Bank, Citation2010). There have also been important gender gaps in access to agricultural extension mainly due to the limited participation of female farmers in extension-related meetings. The situation is worsened by the critically low number of public extension personnel. For instance, in Tanzania, there are approximately 7,030 extension workers which translates to an extension worker – farmer ratio of 1:831 (Mabaya et al., Citation2017). In Uganda, by 2016 about 2,000 extension workers were serving a farming population of over 5 million households, and subsequently, only 5% of farmers reported to have accessed extension services in 2016/17 (UBOS, Citation2018). Similarly, in Ghana, the extension worker – farmer ratio is 1:1850 (MoFA, Citation2019).

Due to limited success in terms of the numbers of farmers reached and technologies transferred and adopted through traditional agricultural extension approaches (Hellin & Dixon, Citation2008), campaign-based extension approaches are gaining prominence as one of the primary means to accelerate awareness about- and adoption of recommended technologies through targeted information (Ihm et al., Citation2015), as well as achieving quick, large-scale change in behaviour and practices (Boa et al., Citation2016). Campaigns harness the ubiquity of mass media and information and communications technologies (ICTs) in the developing world and have the potential to substantially amplify reach even to remote areas that are traditionally under-served by mainstream extension services (Aker, Citation2011; Saravanan et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, the deployment of community-based channels such as the use of local FM radio (Hudson et al., Citation2017), and video-mediated extension (Karubanga et al., Citation2016), complement traditional extension and facilitate diffusion of information. Bentley et al. (Citation2003) model named ‘Going Public’ where technical persons interact in face-to-face sessions with people from many areas at once, usually in places they frequent such as market places, has also been documented.

Campaign-based approaches have been well integrated within the public health and nutrition sectors where their effectiveness has been documented (Rekhy & McConchie, Citation2014). Campaigns involve the purposeful application of multiple media and communication support to achieve quick, large-scale change in behaviour and practices. In agriculture, the use of campaign-based approaches is still limited. Existing literature tends to focus on the role of ICTs in agricultural information access for example (Galadima, Citation2014; Hassan et al., Citation2010; Ihm et al., Citation2015; Kansiime et al., Citation2019; Ortiz-Crespo et al., Citation2020). These studies provide useful insights on the use of digital platforms in agricultural extension, however, a dearth of knowledge remains on how campaigns work in agriculture and their potential contribution to enhancing farmer knowledge and bringing about behaviour change. In particular, the process and complexities of implementing integrated multi-partner and multi-technology campaigns are less documented.

This paper documents experiences and lessons learned in the implementation of extension campaigns by the Africa Soil Health Consortium (ASHC) programme. Specifically, this review paper documents; (1) the process for development and delivery of multi-media campaigns, (2) campaign interventions by the ASHC programme and their effectiveness, and (3) key success factors for campaigns to guide future agricultural extension campaigns. The ASHC scale-up campaigns utilized a variety of media and interpersonal approaches to promote proven (in agronomic and economic terms) SAI practices and technologies for key crops (maize, common bean, soybean, cassava, potato, and banana) in four African countries – Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda. The campaign approach enabled the team to test the use of multiple media – print, radio, SMS, drama, comics, intermediaries such as agro-dealers and village-based advisors (VBAs), and village-based film screenings – in reaching men, women, and youth within the farming households. VBAs are trained farmers equipped with information materials and small seed packs of improved varieties and other inputs which they share with farmers for free to promote learning through the ‘mother and baby’ approach.

2. ASHC campaign model

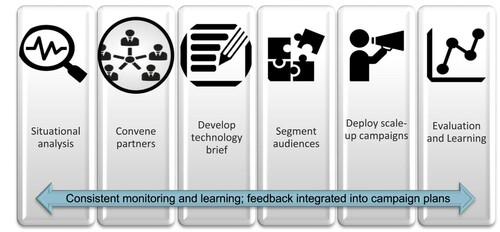

The ASHC campaign approach was premised on a theory of change: that employing improved information design, producing farmer-centric materials, and delivering consistent messages through well-coordinated multiple media, multi-partner scale-up campaigns would lead to increased awareness of improved technologies and approaches and promote uptake of SAI practices by small-scale farming households. Implementation of ASHC campaigns employed rigorous planning, monitoring, and evaluation activities to ensure the campaign work remained on track to achieve the intended targets. The campaigns were implemented in a multi-partner environment, employing complementary communication approaches. shows the ASHC campaign model.

Situational analysis: Each campaign activity commenced with a situation analysis and formative appraisal. This involved focus group discussions (FGDs) with farmers in selected villages or household surveys chosen in a way that is representative of the region(s) where the campaigns were to be held. At this stage, information was gathered on farmer knowledge, practices, and information gaps, communication channels accessible to men, women, and youth, and preferred timing and format of messages. During this phase, the teams also assessed existing initiatives related to the commodity of interest, stakeholders at play, and alignment with local contexts including relevant policies and country development agenda.

Convening of partners: The campaigns were participatory and leveraged the distinct but complementary roles of different partners who included: (a) knowledge partners (national research institutions who have the technical knowledge on technologies); (b) delivery partners (active participants in information supply chains through mass media and other extension approaches and have direct contact with farmers); (c) input-output market players (active participants in input and output supply chains); and (d) communication and research partners (partners who worked with the ASHC team to carry out situation analyses and learn lessons around communication and evaluate outcomes).

Technical brief and content development: A technical brief is a collation of information related to a particular commodity and its recommended SAI practices, and formed the core reference for developing messages to support the scale-up campaigns. Key content in the brief was jointly agreed upon with partners.

Audience segmentation: This entailed development of communication materials that are tailor-made for end-users of different gender and socio-economic differentiation. Farmers and farmer representatives played a key role at this stage in shaping materials to meet their needs. Prototypes of the developed materials were tested for their usability and acceptability (in terms of content and format) with targeted audiences. Outcomes and lessons at this stage were used to improve the design of the scale-up campaign and contributed to the lessons from the programme.

Scale-up campaign: This involved delivering messages from the technology brief using a mix of communication approaches. In some cases, pilot campaigns to test approaches in relatively small areas were used to learn lessons and inform campaign activities at a larger scale in terms of partnerships, geographical coverage, and the number of farmers reached. The campaigns leveraged complementarities of various channels aimed at reaching different members of the farming household as units of information diffusion, considering variations in literacy levels, social-cultural dynamics, and interests. The campaigns were implemented to align with the cropping calendars for the respective counties/regions/states thereby providing timely information to facilitate farmers’ decision-making based on the growth stage of planted crops.

Monitoring, evaluation, and learning: These activities measured the reach of the messages and changes in knowledge, attitude, and practices about the promoted technologies and also assessed the added value of the campaign approach to conventional extension methods. Reach was estimated based on those who saw or read, listened to any of the campaign messages, or participated in demonstrations, field days, VBA ‘mother-baby’ trials, etc. Estimation of radio reach was based on radio signal strength, the adult population in coverage areas, and the proportion of those who listened to at least one episode based on farmer surveys (Hudson et al., Citation2017).

3. ASHC campaign interventions and key results

Between 2015 and 2018, ASHC delivered 18 campaigns focusing on maize, common bean, soybean, cassava, potato, and banana in four African countries – Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda. The ASHC programme leveraged funding from other multi-partner projects; SILT (Scaling Improved Legume Technologies), UPTAKE (Up-scaling Technologies in Agriculture through Knowledge and Extension), and GALA (Gender and the Legume Alliance: Integrating Multimedia Communication Approaches and Input Brokerage). Each campaign was designed with specific key messages, delivery channels, and scale depending on target audience needs and preferences observed during formative appraisals. Primarily, the campaigns employed radio programming, community video screening, short message service (SMS) sent through mobile phones, printed materials, demonstration plots, and the VBA extension model, often in an integrated manner. The aims and strategies of the key campaign programmes are discussed below, and the evaluations of the campaigns are summarized in . Annex 1 shows the estimation of reach for the 18 campaigns. Considering that some case studies collected more information than others about the number of farmers receiving information from different sources, we report numbers separately for each type of communication to avoid instances of double counting.

Table 1. Summary of key campaign activities to promote SAI activities by ASHC.

3.1. Common bean and soybean campaigns in Tanzania

The ASHC programme delivered a common bean campaign in Northern Tanzania in 2015 named ‘Maharage Bingwa’ (the winning bean) integrating the use of radio programmes and Shujaaz comics. Comics were particularly targeted to young audiences (15–24 years) and included a 6-page story featuring common bean under the ‘Maharage Bingwa’ tagline and a follow-up storyline with the ‘Hustla’ tagline (i.e. someone finding a way to make money, usually outside of formal employment). In 2016, the SILT project, jointly led by Farm Radio International (FRI), CAB International (CABI), Africa Fertiliser and Agribusiness Partnership (AFAP) in partnership with the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), Wageningen University and Research (WUR) and the Agricultural Seed Agency (ASA), implemented a follow-up common bean campaign in Northern Tanzania and a soybean campaign in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. The SILT campaign employed radio programming, printed materials (extension manuals and posters), demonstration plots, and VBAs. The proven innovation at the core of the campaign was rhizobia inoculation for soybean, which is widely documented to be key to improved legume technologies (Ndakidemi et al., Citation2006), with some pilots on common bean. This was promoted in conjunction with information on; new legume varieties with wide-ranging benefits (taste, enhanced nutrition, better markets, disease resistance, productivity); enhanced seed quality; good agricultural practices; the soil regenerative role of legumes in intercrops and rotations; the value of blended phosphate and multi-nutrient fertilizers in enhancing legume production; harvesting and post-harvest handling practices, use of Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) bags, and market information.

A series of evaluative activities were undertaken to understand the effectiveness of specific campaign components and the overall campaign. Evaluation of the effectiveness of VBAs and the use of extension-support materials was done in April 2016 using data gathered through FGDs involving 102 farmers (37% female) in the communities where VBAs operated, and interviews with 11 VBAs (Kansiime et al., Citation2018). Results showed that VBAs played an important role in reaching a wide audience of farmers with common bean technologies and consequently new production technologies to rural farming communities. At least 90% of the FGD participants mentioned VBAs as their main source of agricultural advice and the primary source of information on common beans. Farmers mentioned that they received from VBAs specific information on; sowing and spacing of common bean, fertilizer application, new bean varieties, and pest and disease management, which was in line with the promoted practices by VBAs. Over 60% of those who had received information from VBAs indicated that they took up one or more of the promoted common bean practices. Extension materials facilitated VBA engagement of farmers even in informal settings, enhancing information flows beyond village boundaries (Kansiime et al., Citation2018).

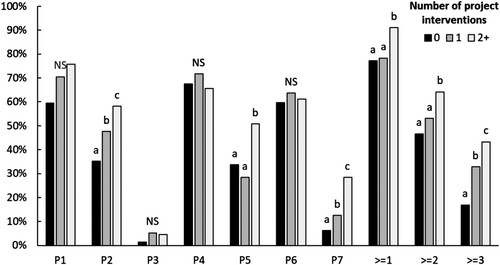

An outcome evaluation of the entire campaign was undertaken by partner FRI between January and February 2018 using a two-stage cluster sampling procedure to ensure the selection of respondents in areas reached by radio, those that hosted the demonstration plots, and communities that had received Shujaaz comics. In total 1,886 randomly selected households were surveyed in face-to-face interviews (Hampson et al., Citation2018). Data showed that 14.3%, 8.3%, 3.6%, and 0.4% of the surveyed households had listened to a radio programme, participated in demonstrations, received printed material or comics on common bean respectively. Data further showed a positive influence of the three main project activities – radio, demonstration plots, and printed materials – on the uptake of improved varieties of common beans, PICS bags, and use of fertilizer. Although used by a high proportion of farmers, practices such as incorporation of residue, following the proper harvest time and the recommended weeding, were not significantly influenced by the project, suggesting that these practices were already relatively well-established among farmers. Given the low response rate for some interventions, it was not possible to look at all the possible combinations of project activities, however, to capture the idea of ‘synergy’ among the four types of project activities, the study classified the respondents into those exposed to ‘none’, ‘one’ or ‘two or more’ of the project activities, regardless of what they were. Results showed that the proportion of respondents taking up new technologies increased as the number of information sources they were exposed to increased ().

Figure 2. Percentage of respondents using each of the improved practices and practising more than 1, 2, or 3 practices for respondents exposed to 0, 1, or 2 or more project interventions. For each practice, bars with a different letter are significantly different. Practices: P1. Incorporation of residues when preparing the land, P2. Use of improved varieties of common beans, P3. Use of recommended spacing for row planting, P4. Use of recommended weeding, P5. Use of fertilizer with common beans, P6. Following proper harvest time, P7. Use of PICS bags. Source: (Hampson et al., Citation2018).

3.2. Maize campaign in Tanzania

Two maize campaigns were implemented during the 2016/17 and 2017/18 cropping seasons. The maize campaigns were implemented under the UPTAKE project, in the Eastern zone and Southern Highlands of Tanzania. The campaigns were jointly implemented by FRI, CABI, district agriculture offices, and the Tanzania Agricultural Research Institutes (TARI – Selian, Kibaha and Uyole). Two complementary ICT-based channels (i.e. radio and mobile SMS messages) were used. Short messages were disseminated by Esoko (a commercial agricultural profiling and messaging service), and radio broadcasts through two local FM stations. Disseminated messages included the use of Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs), improved seed varieties, scouting, and identification of key crop pests including the fall armyworm, recommended pesticides and judicious application for pest management (including public health and safety measures). Dynamic messages were also sent out to address emerging issues in the cropping season, e.g. pest outbreaks, and changes in weather patterns. During the campaign, about 3.9 million SMS were disseminated to 110,769 maize farmers profiled on Esoko platform. Estimation of radio campaign reach was not done for this project, but estimates on listenership during other projects showed that the rural working-age population (potential reach) in the areas served by five stations (Baraka FM and Ilasi FM for maize) and (Safina FM, Utume FM, and Sauti ya Injili for beans) was approximately 4.6 million people.

The campaigns were evaluated through two telephone follow-up surveys which were conducted in 2017 (241 respondents) and 2018 (352 respondents). In addition, 40 FGDs and eight key informant interviews (KIIs) were held in 2018. The findings indicated that 80% of sampled farmers learned something new following the campaigns. Awareness of – and the probability of adopting new technologies were boosted where SMS supported radio campaigns. In terms of cost-effectiveness, radio alone was considered the most cost-effective approach; one dollar spent on the radio campaign resulted in 2.1 farmers that adopted at least one new practice and technology compared with 0.5 farmers for SMS and 0.4 farmers for radio and SMS combined (Silvestri et al., Citation2020). Karanja et al. (Citation2020) showed that 62% of the farmers who reported receiving SMS had implemented changes in their agricultural practices. The most common changes cited by respondents, which they attributed to receiving SMS, were scouting and monitoring for pests, both in the field and in stored products, improved land preparation, and use of improved seed (Karanja et al., Citation2020). Input suppliers involved in the campaigns corroborated the result on the use of improved seed indicating that they handled far more inquiries than usual and increased sales of the improved varieties. Four of the five companies that sold the Uyole Hybrid (UH) varieties reported that, for the first time, they had no stocks to carry over to the next planting season.

3.3. Soybean campaign in Nigeria

In Nigeria, two soybean campaigns were implemented, linked to public and private sector partners in the legume value chain, including Notore, a Nigerian fertilizer company, the IITA business incubation platform (BIP), and the N2Africa project. The link to the private sector was intended to ensure input availability and that value chain obstacles to support farmer adoption of soybean technologies were addressed. The campaign messages were disseminated by IntrioSynergy Ltd., an agro-input and technology promotion agency. In 2017, soybean posters and manuals were developed and disseminated to at least 30,582 soybean farmers in five states (Benue, Kwara, Niger, Kaduna, and Borno). In 2018, the campaign was expanded to include Nasarawa State, an area where there was no previous exposure to N2Africa initiatives. In addition to printed materials, five radio stations (one per state) were engaged to broadcast soybean messages reaching an estimated 136,031 listeners.

The campaign was evaluated through a survey of 250 randomly selected soybean farmers, and 108 key informants (extension workers, radio broadcasters, and agro-dealers). Respondents were drawn from the 6 states where the campaign was implemented. Results showed significant differences in the application of practices before and after receipt of the campaign messages concerning the use of improved seeds, line planting, and how to access markets for selling soybean. The receipt of campaign messages significantly contributed to the increased use of soybean technologies by farmers. The evaluation further showed that farmers’ exposure to and understanding of messages was increased by the use of multiple media (Musebe et al., Citation2019). Messages on inoculants led most extensively to their use compared to other inputs and practices and were motivated by clarity on usage, expected benefits, and ease of access to the inoculants, marketed under the brand name NoduMaxTM.

3.4. Soybean campaign in Ghana

The soybean campaign was implemented in Northern Ghana by ASHC and the GALA project. Two campaigns were delivered in 2017 and 2018 in partnership with Countrywise Communications Ghana, a social enterprise, to produce short music films and videos on soybean agronomy that were used during the campaign. In both campaigns, village-based video screenings and music films reached about 70,818 and 44,883 people respectively. Printed materials were distributed during the village screenings. The campaigns were implemented in the Northern, Upper East and Upper West regions. The film-video formats were supplemented by music videos, featuring two popular local musicians, which advocated growing soybean and explained the key agronomic practices.

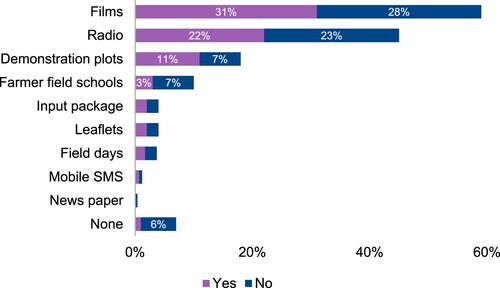

A Computer-Aided Telephone Interview (CATI) survey was conducted by partner iLogix in September 2018, comprising 3,009 farmers drawn from 35 districts in the campaign regions. The CATI survey targeted households that had been surveyed at the start of the project in 2017 to compare changes in practices that could be attributed to the project activities. Results showed that 46% of the respondents were aware of inoculants; 31% through films (). Out of the soybean farmers, 16% used inoculants, half of these from a commercial source, agro-dealer (40%), local market (7%), farmer association (1%), and outgrowing scheme (1%). Before the campaigns, inoculants had not been commercially available to smallholder farmers in the target areas at agro-dealer or local market levels (Green-Ef report 2019). In comparison to households that were interviewed in the baseline, an increase in adoption rate (between 4–16%) was registered for crop rotation, chemical weeding, fertilizer use, manure use, and use of PICS bags. Results further showed that the use of multiple delivery and communication approaches had a positive effect on the uptake of improved practices and technologies, in particular, improved seeds, early planting, and inoculants.

3.5. Banana agronomy campaign in Uganda

A campaign on banana agronomy was carried out with project partners in Uganda – National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO), the lead partner, CABI, Bioversity International, IITA, government extension, and farmer cooperatives. ASHC championed the development of appropriate communication materials to be disseminated via radio and drama film screenings. Practices promoted through the campaign include; pest control, disease management, soil fertility management, and soil and water conservation.

The radio programming was interactive, including live shows, call-in by listeners, and poll questions. The radio campaign aired over 12 weeks through five radio stations in central and western Uganda, during February and April 2019. For poll questions, listeners responded by sending a free SMS through the provided toll-free short code indicating their location and gender. The poll questions covered the campaign topics, also, sought to understand the crop farmers considered most important, hindrances to producing marketable banana bunches, challenges faced in applying manure, and soil and water conservation practices and practices used to control banana pests and diseases. At least 20,525 (24.5% female) responses were obtained from the poll questions which also showed that the radio campaign was listened to in 56 districts countrywide. Film screenings comprised 5 episodes of banana drama aired in December 2019 in the local languages of Luganda and Runyankore in central and western Uganda respectively. Each episode lasted about 15 min on average. A total of 15 screenings were carried out in 5 villages. At least 2,266 persons (41.5% male, 33% female, 14.8% teenagers, and 10.7% children) attended the village screenings. Prior, interpersonal extension approaches including; demonstration plots, farmer/extension staff training, and farmer field days were implemented, along with the distribution of printed materials (December 2018).

A project mid-term review done in July 2019, through a survey of 587 farmers (136 from the three-project sites and 451 from sub-counties neighbouring the project sites) showed that over 90% of the respondents in the project sites attested to receiving information on banana agronomy. The most common sources of information were NARO/project staff, demonstration plots, radio programmes, farmer meetings, and extension agents in that order. Adoption of promoted technologies was observed both in the project sites and the neighbouring villages, although there was a significantly higher number of adopters in the project sites compared to those in the neighbourhood across the board. Compared to baseline, uptake of pest control practices and soil fertility management by farmers in the project site increased by 25% and 21% respectively.

4. Effectiveness of ASHC campaign-based extension approaches

The broad aim of the campaigns was to deliver information to enable the adoption of proven SAI practices and technologies at scale. The effectiveness of the campaigns was examined using two criteria: (1) the number of farmers reached with information on SAI practices and technologies, and (2) the success of the campaigns in influencing uptake of promoted SAI practices and technologies. It is acknowledged, however, that comparison between the different campaigns discussed above is challenging as each had its own unique set of assumptions, target audience, criteria, and methodology for measuring success. The studies relied on information reported by farmers before and after participation in the campaigns and did not make an actual comparison between those who participated and those that did not (control) which may lead to bias in the reported adoption rates for farmers. On the other hand, the existence of social relations in communities contributes to unofficial communication patterns, which may amplify messages beyond the target areas. Given these scenarios, our estimate of reach may not be accurate but provides a practical approach to reach estimation based on the type of channel used, and subsequently points to the ability of campaigns to reach scale in comparison to conventional extension approaches.

Evaluation of the various campaigns shows that they contributed to increased awareness and knowledge about promoted technologies, in some cases leading to significant adoption rates. Hampson et al. (Citation2018) showed that the common bean campaign led to 20% of the farmers reached applying at least one improved technology. This adoption rate compares favourably to reported adoption rates for the training and visits extension approach: 1% to 7% for complex technologies that required the purchase of inputs, and between 11% and 21% for simple technologies that do not require the purchase of inputs (Akpoko & Kudi, Citation2007). Extension approaches with high adoption rates such as farmer field schools (reported 20% to 60% rate) are criticized for their high cost of administration and limited farmer reach compared to other approaches (Quizon et al., Citation2001). While costs associated with campaign approaches used were not explicitly examined, some studies have shown that mass media approaches (e.g. mobile, print, and radio) have the lowest per farmer cost and due to the low cost of these programmes, have an associated high reach potential (Harris et al., Citation2012; Kansiime et al., Citation2017; Ricker-Gilbert et al., Citation2008).

A multi-channel approach leveraged complementarities of mass media (such as radio, SMS, and social media), one-to-many interpersonal approaches (such as group screenings of videos and demonstration plots), and one-to-one interpersonal approaches (such as VBAs). Although the effectiveness of actual channel combinations was not easily assessed, evaluation results showed that exposure to multiple communication approaches was associated with increased uptake of promoted technologies. Silvestri et al. (Citation2020) showed a higher awareness and adoption of legume practices when SMS was combined with radio programming. Similarly, Musebe et al. (Citation2019) showed a positive contribution of multimedia messages to productivity and diversity in the practices taken up by farmers. Similar results have been reported in other studies, for example (Tambo et al., Citation2019) showed that exposure to multiple campaign channels yielded significantly higher outcomes than exposure to a single channel, with some evidence of additive effects. In particular, combining radio with video screenings almost doubled the levels of awareness of fall armyworm and its management and doubled the number of practices used by farmers. Karubanga et al. (Citation2016) showed greater potential for integration of video-mediated extension and face-to-face extension approaches as the two are complementary in the various stages of the farmer learning – awareness creation – knowledge acquisition and retention respectively.

The ASHC campaigns differed based on the intensity and clarity of the message, channel used, and technologies being promoted. Some approaches were particularly strong in creating awareness and providing information (e.g. radio) while others in skills development and facilitating uptake of technologies especially complex ones e.g. demonstration plots. Kansiime et al. (Citation2020) showed that demonstration plots and agro-dealers were important information sources in promoting production inputs and more recently introduced practices (such as soil testing, use of inoculants, and PICS bags) that require hands-on skills, while Ragasa et al. (Citation2021) showed that radio programmes helped in promoting the adoption of crop diversification and intensity of adoption of crop residue incorporation only, considerably simple technologies as opposed to technologies that would be seen as complex or too labour-intensive. Also, Ragasa et al. (Citation2021) showed that radio programming had strong positive impacts on technology awareness, but a limited impact on actual adoption. However, modified listening groups linked to radio programmes have been found to enable learning of technical concepts, and offer useful platforms that strengthen social capital and cooperation among listeners (Pasiona et al., Citation2021; Ragasa et al., Citation2021). Therefore exposure to multiple sources of information that combine virtual environments and interactive techniques should be promoted to enhance learning and increase knowledge retention as reported elsewhere (Ibrahim & Al-Shara, Citation2007).

The ASHC campaign approach was responsive to the impact of differential access to and utilization of information by different farmer categories, as well as access and control of communication devices and preference of communication channels, by integrating methods that appealed to different gender groups and those that brought families and communities together e.g. video screenings. Men were more likely to listen to radio compared to women, while women tended to rely more on community-based information sources such as demonstration plots, radio listening groups, and village video screenings. These differences in preference of information sources have been reported elsewhere (Ihm et al., Citation2015; Irungu et al., Citation2015), though not analogous due to impacts of other socio-cultural factors like education, workload and social networks (Ragasa et al., Citation2021; Tata & McNamara, Citation2018) on the use of technology and extension service delivery. To enhance learning and participation in extension programme for all segments of society, gender responsive extension approaches should be adopted.

ASHC campaigns involved multiple stakeholders including the private sector and policymakers, which brought additional benefits for participating farmers. The linkages were also critical for ensuring sustainable access to information, services, and inputs by farmers. In Nigeria, linking the campaign activities to the government’s Anchor Borrowers programme (an initiative that aims to improve the availability of inputs to soybean farmers through a concessionary loan scheme), enabled the ASHC team to increase the number of farmers reached in 2018–170,452, up from 30,582 farmers in 2017. In Tanzania, although it was widely known that farmers preferred a common bean variety that could only be obtained in Kenya, the SILT telephone survey interviews provided new insights into the scale of this farmer and market preferred bean variety being cultivated, even though it was not a registered variety in Tanzania. This evidence provided the impetus for a policy change that led to the registration of this preferred variety and to become legally available in Tanzania which is unlikely to have happened without this evidence being provided. In Ghana, the evidence generated by the analysis of the behaviour of farmers around inputs triggered collaboration between YARA Ghana, a fertilizer company, and the N2Africa project focused on Nitrogen fixation, which led to the development of a new fertilizer blend (New YARA Legume). Also, the Ghanaian Ministry of Food and Agriculture included soybean in their Planting for Food and Jobs scheme and recognized inoculants and P-blended fertilizer for soybean to be effective and part of the key pool of inputs to be subsidized under this scheme.

5. Key factors that influenced the success of ASHC campaigns

Development of relevant and localized content: The ASHC programme, through multi-partner processes, ensured the development of relevant content and fit-for-purpose information materials, informed by formative appraisals. The materials are freely available for use by stakeholders on the ASHC materials library (https://www.africasoilhealth.org/). The content was validated by stakeholders and then signed off by authorized government agencies before each campaign to ensure harmonized messaging. The need to develop relevant, localized, and scalable content that is user-cantered has been underscored in previous studies (Irungu et al., Citation2015; Saravanan, Citation2010; Steinke et al., Citation2020).

Multi-partner approaches: ASHC developed and implemented a successful partnership model that helped mobilize at least 70 different agencies to participate in campaigns. This unique feat was achieved by recognizing and harnessing the different but complementary strengths of partners, which helped to sustain their interest over time and gave the much-needed momentum to deliver different campaigns for more than one season. Notably, the work under the banner of the Legume Alliance was important in bringing together stakeholders in the common bean and soybean value chains in Tanzania, Ghana, and Nigeria, facilitating joint activities, learning, and experience sharing. The model was developed through iterative learning and adjustment cycles working in an action research model and using mixed methods to evaluate and learn lessons. The collaboration also helped to promote a consistent message across all stakeholders and the community and assisted in the creation of a larger pool of funds available for promotional initiatives. The team worked to support scaling in other programmes including the Bill and Melinda Gates (BMGF) Foundation-funded N2 Africa and banana agronomy initiatives; the World Bank-funded Agricultural Technology and Agribusiness Advisory Services (ATAAS) project implemented by NARO in Uganda and the Scaling Seeds and Technologies Partnership in Africa (SSTP) in Tanzania, and the AGRA-funded Optimizing Fertilizer Recommendations in Africa (OFRA), among others.

Deployment of innovative information channels targeting different audience categories: the ASHC programme integrated innovative and tailor-made approaches to enhance campaign efficiency. For example, some ASHC campaigns integrated community radio listening groups which facilitated communities outside the radio signal to access recorded radio programmes. The radio listening groups were organized alongside demonstration plots, facilitating knowledge exchange, and learning. Illustrative and fit-for-purpose printed materials also provided reference information for extension workers and community facilitators during face-to-face interactions, as well as farmers. Multi-channel approaches mediate and provide interfaces between human and non-human networks and support decision making, learning and innovation (Klerkx, Citation2021).

6. Conclusion

The evidence emerging from multiple media, multi-partner campaigns led by ASHC suggests that this approach offers advantages and benefits compared to other less coordinated approaches for reaching farmers at scale with information on improved practices and technologies in the broad context of sustainable agricultural intensification. The ASHC experience further highlights the effectiveness of campaigns as complements to more conventional extension programmes. This matches evidence from the human health and nutrition fields where these approaches are more common. However, adoption varies based on the nature of the practice or technology being promoted, farmer motivating factors such as access to input and output markets, farmer investment capacity, the value of the crop, etc. It can be argued; these factors generally influence adoption decisions as well and are not necessarily linked to the approach used to disseminate information. The wide array of technological options available and their interactions requires farmers to identify a logical stepwise sequence for adoption that fits their socio-economic circumstances. There is a need to provide more tailored information through a stepwise approach, i.e. presenting farmers with subsequent agronomic options that range from low to high investments and which is tied to farmers’ investment capabilities, and demonstratable productivity gains. A stepwise investment can optimize the return on investment for farmers against their financial capacity and encourage them into a positive cycle of on-farm investment, provided the output markets hold up.

Acknowledgments

The ASHC program was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), SILT was funded by International Development Research Centre (IDRC), GALA was funded by United Kingdom (Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office) through WYG's Sustainable Agricultural Intensification and Learning in Africa (SAIRLA) programme, and UPTAKE was funded by International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). Respective project implementing partners as indicated in the project description are acknowledged for their contribution to the projects. Other project partners included; Farm Inputs Promotions Africa (FIPS-Africa), Well Told Story (Shujaaz Inc.), Agricultural Seed Agency (ASA) Tanzania, Esoko, Countrywise Communications Ghana, Nigeria Soybean Innovations Lab, the N2Africa project, and Green-Ef Nigeria. Authors also acknowledge the contributions of project principal investigators/leaders; David Kijazzi and Dr. Msola Mbette Mshindo (AFAP Tanzania); Karen Hampson (FRI Tanzania), Dharmesh Ganatra (iLogix Kenya), Raymond Vuol (Countrywise Communications Ghana), Dr. Jerome Kubiriba (NARO Uganda) and other partners who played a key role in the implementation of the various campaigns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aker, J. C. (2011). Dial “A” for agriculture: A review of information and communication technologies for agricultural extension in developing countries. Agricultural Economics, 42(6), 631–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2011.00545.x

- Akpoko, J., & Kudi, T. (2007). Impact assessment of university-based rural youths agricultural extension out-reach program in selected villages of Kaduna State, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences, 7(21), 3292–3296. https://doi.org/10.3923/jas.2007.3292.3296

- Bentley, J. W., Boa, E., Van Mele, P., Almanza, J., Vasquez, D., & Eguino, S. (2003). Going public: A new extension method. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 1(2), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2003.0111

- Bentley, J. W., Danielsen, S., Phiri, N., Tegha, Y. C., Nyalugwe, N., Neves, E., Hidalgo, E., Sharma, A., Pandit, V., & Sharma, D. R. (2018). Farmer responses to technical advice offered at plant clinics in Malawi, Costa Rica and Nepal. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 16(2), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2018.1440473

- Boa, E., Franco, J., Chaudhury, M., Simbalaya, P., & Van Der Linde, E. (2016). Plant Health Clinics Note 23. GFRAS Good Practice Notes for Extension and Advisory Services. GFRAS, Lausanne, Switzerland.

- Galadima, M. (2014). Constraints on farmers’ access to agricultural information delivery: A survey of rural farmers in yobe state, Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science, 7(9), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.9790/2380-07921822

- Gunton, R. M., Firbank, L. G., Inman, A., & Winter, D. M. (2016). How scalable is sustainable intensification? [Comment]. Nature Plants, 2(5), 16065. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2016.65

- Hampson, K., Sones, D., & Watiti, J. (2018). Scaling-up improved legume technologies in Tanzania (SILT). https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/57098/57149.pdf.

- Harris, M. L., Norton, G. W., R, K. A. N. M., Alwang, J., & Taylor, B. D. (2012). Bridging the information gap with cost-effective dissemination strategies: The case of integrated pest management in Bangladesh. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 45(4), 639–654. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1074070800005174

- Hassan, M. S., Shaffril, H. A. M., Shahkat Ali, M. S., & Ramli, N. S. (2010). Agriculture agency, mass media and farmers: A combination for creating knowledgeable agriculture community. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 5(24), 3500–3513.

- Hellin, J., & Dixon, J. (2008). Operationalising participatory research and farmer-to-farmer extension: The kamayoq in Peru. Development in Practice, 18(4-5), 627–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520802181889

- Hudson, H. E., Leclair, M., Pelletier, B., & Sullivan, B. (2017). Using radio and interactive ICTs to improve food security among smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommunications Policy, 41(7), 670–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2017.05.010

- Ibrahim, M., & Al-Shara, O. (2007). Impact of Interactive Learning on Knowledge Retention. Human Interface and the Management of Information. Interacting in Information Environments, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- IFPRI – World Bank. (2010). Gender and governance in rural services: Insights from India, Ghana, and Ethiopia (Agriculture and Rural Development, Issue.

- Ihm, J., Pena-Y-Lillo, M., Cooper, K. R., Atouba, Y., Shumate, M., Bello-Bravo, J., Malick Ba, N., Dabire-Binso, C. L., & Pittendrigh, B. R. (2015). The case for a two-step approach to agricultural campaign design. Journal of Agricultural & Food Information, 16(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496505.2015.1033529

- Irungu, K. R. G., Mbugua, D., & Muia, J. (2015). Information and communication technologies (ICTs) attract youth into profitable agriculture in Kenya. East African Agricultural and Forestry Journal, 81(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00128325.2015.1040645

- Kansiime, K. M., Mulema, J., Karanja, D., Romney, D., & Day, R. (2017). Crop pests and disease management in Uganda: status and investment needs. http://p4arm.org/app/uploads/2015/02/uganda_crop-pests-and-disease-management_full-report_vWeb.pdf.

- Kansiime, M. K., Alawy, A., Allen, C., Subharwal, M., Jadhav, A., & Parr, M. (2019). Effectiveness of mobile agri-advisory service extension model: Evidence from Direct2Farm program in India. World Development Perspectives, 13, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2019.02.007

- Kansiime, M. K., Macharia, M., Baars, E., Rutatora, D. F., Silvestri, S., & Njunge, R. (2020, December). Evaluating gender differentials in farmers’ access to agricultural advice in Tanzania: An intra-household survey. CABI working paper 16.

- Kansiime, M. K., Watiti, J., Mchana, A., Jumah, R., Musebe, R., & Rware, H. (2018). Achieving scale of farmer reach with improved common bean technologies: The role of village-based advisors. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2018.1432495

- Karanja, L., Gakuo, S., Kansiime, M., Romney, D., Mibei, H., Watiti, J., Sabula, L., & Karanja, D. (2020). Impacts and challenges of ICT based scale-up campaigns: Lessons learnt from the use of SMS to support maize farmers in the UPTAKE project Tanzania. Data Science Journal, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-007

- Karubanga, G., Kibwika, P., Okry, F., & Sseguya, H. (2016). Empowering farmers to learn and innovate through integration of video-mediated and face-to-face extension approaches: The case of rice farmers in Uganda. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 2(1), 1274944. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2016.1274944

- Kassie, M., Teklewold, H., Jaleta, M., Marenya, P., & Erenstein, O. (2015). Understanding the adoption of a portfolio of sustainable intensification practices in eastern and southern Africa. Land Use Policy, 42, 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.08.016

- Klerkx, L. (2021). Digital and virtual spaces as sites of extension and advisory services research: Social media, gaming, and digitally integrated and augmented advice. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 27(3), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2021.1934998

- Mabaya, E., Mzee, F., Temu, A., & Mugoya, M. (2017). Tanzania Brief 2017 - The African Seed Access Index. The African Seed Access Index. https://tasai.org/reports.

- MoFA. 2019. Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2019-2022. Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA), Accra - Ghana.

- Musebe, R., Watiti, J., Duah, S., & Okuku, I. (2019). Using multimedia campaign approach to improve farmer knowledge on soybean production: A case of selected states in Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 10(24), 1–13. www.iiste.org. https://doi.org/10.7176/JESD/10-24-01

- Ndakidemi, P., Dakora, F., Nkonya, E., Ringo, D., & Mansoor, H. (2006). Yield and economic benefits of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and soybean (glycine max) inoculation in northern Tanzania. Animal Production Science, 46(4), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1071/EA03157

- Ortiz-Crespo, B., Steinke, J., Quirós, C. F., van de Gevel, J., Daudi, H., Gaspar Mgimiloko, M., & van Etten, J. (2020). User-centred design of a digital advisory service: Enhancing public agricultural extension for sustainable intensification in Tanzania. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1720474

- Pasiona, S. P., Nidoy, M. G. M., & Manalo Iv, J. A. (2021). Modified listening group method as a knowledge-sharing and learning mechanism in agricultural communities in the Philippines. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 27(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2020.1816477

- Quizon, J., Feder, B., & Murgain, R. (2001). Fiscal sustainability of agricultural extension: The case of the farmer field school approach. Journal of International Agriculture and Extension Education, 8(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240185300041

- Ragasa, C., Mzungu, D., Kalagho, K., & Kazembe, C. (2021). Impact of interactive radio programming on agricultural technology adoption and crop diversification in Malawi. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 13(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2020.1853793

- Rekhy, R., & McConchie, R. (2014). Promoting consumption of fruit and vegetables for better health. Have campaigns delivered on the goals? Appetite, 79, 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.04.012

- Ricker-Gilbert, J., Norton, G. W., Alwang, J., Miah, M., & Feder, G. (2008). Cost-effectiveness of alternative integrated pest management extension methods: An example from Bangladesh. Review of Agricultural Economics, 30(2), 252–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9353.2008.00403.x

- Saravanan, R. (ed.). (2010). ICTs for agricultural extension. New India Publishing Agency.

- Saravanan, R., Sulaiman, R. V., Davis, K., & Suchiradipta, B. (2015). Navigating ICTs for Extension and Advisory Services.

- Silvestri, S., Richard, M., Edward, B., Dharmesh, G., & Dannie, R. (2020). Going digital in agriculture: How radio and SMS can scale-up smallholder participation in legume-based sustainable agricultural intensification practices and technologies in Tanzania. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1750796

- Steinke, J., van Etten, J., Müller, A., Ortiz-Crespo, B., van de Gevel, J., Silvestri, S., & Priebe, J. (2020). Tapping the full potential of the digital revolution for agricultural extension: An emerging innovation agenda. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1738754

- Tambo, J. A., Aliamo, C., Davis, T., Mugambi, I., Romney, D., Onyango, D. O., Kansiime, M., Alokit, C., & Byantwale, S. T. (2019). The impact of ICT-enabled extension campaign on farmers’ knowledge and management of fall armyworm in Uganda. PLoS ONE, 14(8), e0220844. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220844

- Tata, J. S., & McNamara, P. E. (2018). Impact of ICT on agricultural extension services delivery: Evidence from the catholic relief services SMART skills and farmbook project in Kenya. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 24(1), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2017.1387160

- Thompson, P. B. (ed.). (2008). The Ethics of intensification. The international library of environmental, agricultural and food Ethics (Vol. 16). Springer.

- UBOS. (2018). Uganda National Household Survey 2016/2017. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), Kampala, Uganda.

- UN. (2019). World population prospects 2019: Highlights. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-2019-highlights.html.

- Vanlauwe, B., Bationo, A., Chianu, J., Giller, K. E., Merckx, R., Mokwunye, U., Ohiokpehai, O., Pypers, P., Tabo, R., Shepherd, K. D., Smaling, E. M. A., Woomer, P. L., & Sanginga, N. (2010). Integrated soil fertility management: Operational definition and consequences for implementation and dissemination. Outlook on Agriculture, 39(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000010791169998

- Wiebe, K. (2009). FAO's director-general on how to feed the world in 2050. Population and Development Review, 35(4), 837–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00312.x

- Xie, H., Huang, Y., Chen, Q., Zhang, Y., & Wu, Q. (2019). Prospects for agricultural sustainable intensification: A review of research. Land, 8(157), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8110157

Appendix

Table 1 Annex 1: ASHC’s 18 campaigns and estimated reach per approach used