ABSTRACT

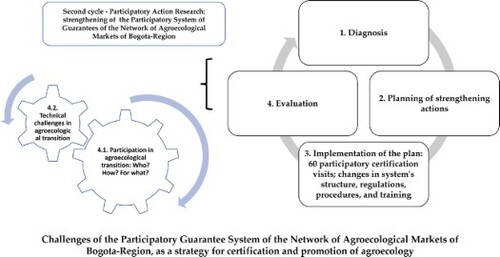

Many Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) are unsustainable because participatory processes requires time. This research focused on the coordination and implementation of actions to strengthen the PGS of the Red de Mercados Agroecológicos de Bogotá Región (RMABR). The methodology was the Participatory Action Research (PAR) with four phases: diagnosis, with semi-structured interviews with the promoters of agroecological markets of the RMABR to identify the state of the PGS; planning of strengthening actions; execution, with sixty participatory certification visits; and, evaluation, to apply opportunities for improvement of the PGS.

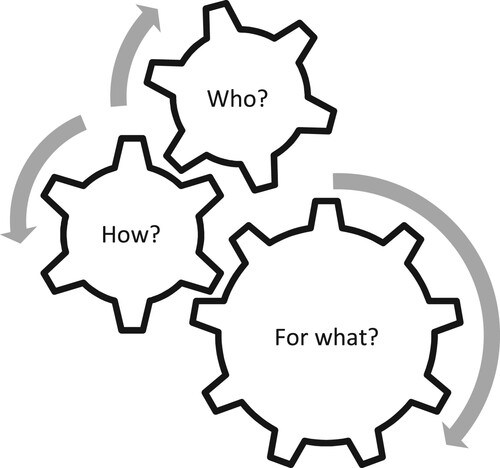

The PGS of the RMABR is an example of governance where assertive participation is essential. Apparently, the main challenge facing the PGS was the contribution of time from its members, especially consumers and producers. However, the real challenge is more complex: who participates (diversity and equity), how (ability, motivation, trust, efficiency, continuity, communication, and procedures) and why (effectiveness), which must be managed assertively with ‘dynamic balance’. Technical challenges persist in the agroecological transition, the greatest in processing, less in livestock, and much less in agricultural production, above all the need to reduce dependence on external inputs persists, difficult given the low availability of family or hired work.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

By 2019, organic agriculture was practiced in 187 countries in which a total of 72.3 million hectares were registered, managed by 3.1 million organic producers, which generated about 106 billion euros in turnover, giving an account of the importance that represents the market for this type of products in the world economy (FiBL; IFOAM, Citation2021). These organic producers are subject to different certification processes to guarantee the nature of their products. The Third-Party Certification – TPC is the most widespread and, in some cases, the most reliable one (Fonacier Montefrio & Taylor Johnson, Citation2019; Hatanaka et al., Citation2005; Kaufmann & Vogl, Citation2018; Padel, Citation2010). This certification system generally involves a regulatory body that establishes production standards, and independent certifying bodies, formally accredited, that through a technical audit verify conformity with criteria defined in legal terms according to the regulations of each country, charging for their operation, taking away autonomy from the producers, ignoring the local context and excluding small producers and lower-income consumers, due to the cost of certification, which considerably raises production costs, and therefore, the price of the products (Cavallet et al., Citation2018; Fouilleux & Loconto, Citation2017; Källander, Citation2008; Nigh & González Cabañas, Citation2005; Raynolds, Citation2004; Sacchi et al., Citation2015; Vogl et al., Citation2005).

Consequently, to meet the demands of conscious consumers without facing the costs and procedures required by TPC, small-scale producers around the world have organized themselves into cooperative networks based on trust, pedagogy, and mutual knowledge to guarantee the quality of their products, developing alternative certification systems, such as Participatory Guarantee Systems – PGS (Binder & Vogl, Citation2018; Cuéllar Padilla & Ganuza Fernández, Citation2018; IFOAM, Citation2008; IFOAM, Citation2013; López Cifuentes et al., Citation2018).

A PGS consists of quality control and certification that takes place among peer producers with a local geographic focus, through the participatory construction, implementation, and monitoring of standards, without the intervention of third-party certification bodies, which promotes food sovereignty and the strengthening of producer and consumer organizations (Fonacier Montefrio & Taylor Johnson, Citation2019; Loconto & Hatanaka, Citation2017; Velleda Caldas et al., Citation2014).

Prior to the emergence of the TCP for organic production, there was no applicable regulation for the production and marketing of organic products, so the trust and social control of the actors involved in the production and marketing chain were the basis that supported the organic quality of the products, which allows us to affirm that the PGS refer to the origin in terms of certification (IFOAM, Citation2013).

The participatory certification process follows three phases common to the vast majority of PGS globally (Pino, Citation2017). In the first phase, a certification commission or committee of members of the markets or associations is defined. In the second phase, a visit to the farm takes place in the presence of the applicant, who participates in the process, at which time information is collected in situ, verifying that practices are in accordance with the established standards; a report is prepared, including the identified opportunities for improvement, which must bear the signatures of the producer and other evaluators. In the third and final phase, the certification commission analyzes the documentation, compares it with the group's standards, and decides on certification (Cuéllar, Citation2009).

Thanks to these procedures, PGS are characterized as inclusive, verifiable, communicable, autonomous, and comprehensive in socio-economic and environmental terms (Chaparro-Africano & Naranjo, Citation2020). Moreover, PGS are the response of organic producers’ organizations to supply local markets with safe food, promoting trust, participation, and knowledge exchange of all actors involved in the production and marketing chain. (Binder & Vogl, Citation2018; Chaparro-Africano & Naranjo, Citation2020; Cuéllar Padilla & Ganuza Fernández, Citation2018; IFOAM, Citation2008; IFOAM, Citation2013; López Cifuentes et al., Citation2018; Nelson et al., Citation2016).

However, some limitations exist, despite the efforts of different networks and organizations of producers and consumers to highlight the benefits of PGS. Among the limitations, there is the high dependence on voluntary work, the lack of legal recognition in some countries, and the heterogeneity of its members, which can generate social and personal conflicts in the verification processes, as well as the dependence on donated resources, which does not necessarily allow PGS to be a panacea in terms of certification (Clark & Martínez, Citation2016; Fonacier Montefrio & Taylor Johnson, Citation2019; Nelson et al., Citation2010).

In Colombia, organic production is certified through TCP (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development MADR, Citation2006), whereas agroecological production is certified by PGS (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development MADR, Citation2017). Consequently, various groups are trying to distinguish agroecology from organic production.

In this context, the PGS of the Red de Mercados Agroecológicos de Bogotá Región – RMABR aims to strengthen production systems in their environmental, social, and economic dimensions seeking sustainability designed during the years 2016-2017. The RMABR includes a definition of agroecology and 20 guiding principles, an organic structure (PGS Committee and participatory certification visit groups), a participatory certification process with their respective formats, and a transition plan to agroecological production.

This research focused on agreeing and implementing a participatory approach to strengthen the PGS of the RMABR. The need to strengthen the PGS of the RMABR derived from the difficulty in making it fully operational, since not all the certification visits were carried out and little follow-up was given to the work plans (improvement or agroecological transition), which apparently is due to the short time available to its participants, and coincides with research results such as that of Hruschka et al. (Citation2021) or López Cifuentes et al. (Citation2018), but it should be analyzed in more detail. In this sense, the research question posed was: How can the PGS of the RMABR be strengthened?

This document present materials and methods of research, results, including regulations, procedures, certification and promotion of agroecology, and training about PGS, then the discussion, and, finally, conclusions.

2. Materials and methods

The following research focused on the agreement and implementation of actions to strengthen the PGS of the RMABR. The research was developed within the framework of the Agroecological Engineering program UNIMINUTO, main headquarters, between 2018 and 2019.

The methodology implemented was Participatory Action Research (PAR), which allowed for research and action through the interaction between external researchers and the RMABR, in the co-construction and evaluation of collective actions to strengthen the PGS. PAR is a systematic methodology that consists of four stages: diagnosis, planning, execution, and finally, evaluation.

Diagnostic stage: This stage was carried out between February 2018 and April 2018. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with the promoters of eight agroecological markets that were part of the RMABR, which made it possible to identify the state of the PGS, especially in terms of the fulfillment of its objectives.

Planning stage: During this stage and based on the results of the diagnosis, some adjustments were designed collectively, consolidated in a work plan of the committee in charge of dynamizing the functioning of the PGS of the RMABR, which contemplated trainings on the structure and functioning of the PGS for the producers of the RMABR, monthly meetings of the PGS committee for which one of the researchers assumed the secretariat of the PGS committee for 16 months, certification visits, socialization and validation of the results of the visits for the issuance of certificates, field schools to support the agroecological transition, design, and implementation of strategies to improve the supply of agroecological raw materials to processors, and follow-up on the implementation of the work plans resulting from the certification visits.

Implementation stage: In fourteen months, sixty participatory certification visits were carried out, resulting in work plans being built. Likewise, three trainings were developed to promoters and producers of agroecological markets on the functioning of the PGS of the RMABR, where the attending producers made contributions according to their perception and needs. Taking these contributions into account, adjustments were also made or proposed to the principles of the PGS and the certification process (deadlines, participatory certification formats), and other activities were programmed to overcome some of the limitations of the agroecological transition process. Most of these activities, such as field schools and the design of strategies for sourcing agroecological raw materials for processors, could not be carried out.

Evaluation stage: The participants in this phase were, in addition to the researchers, the representatives of eight agroecological markets members of the RMABR (some of the producers and other promoters), for a total of ten people. The evaluation process was permanent during the 18 months that the research lasted, establishing agreements during the development of monthly meetings, recorded in minutes, which allowed correcting on the fly the opportunities for improvement of the PGS identified by the producers and promoters of the markets, during the research. It should be clarified that the producers and promoters of the RMABR also have the role of consumers, from which they also contributed to this research.

3. Results

3.1. Organizational structure

The results of the diagnosis showed the need to increase the number of people on the PGS committee of the RMABR so that it would be made up of one delegate from each market, as initially proposed during its creation in 2016, to make it more dynamic, participatory, and so that the information would flow to each market more effectively. The committee was also asked to include delegate producers, achieved in three of the eight markets.

Complementarily, it was decided to clarify some of the functions to be performed by the PGS committee, as follows: promote and coordinate the planning and execution of certification visits; ensure the operability of the PGS; approve the classification of the production systems visited for the issuance of the corresponding certificates, or, failing that, provide support in resolving doubts.

The financing of this research allowed, during three semesters, to dynamize many functions of the PGS committee: committee secretary, visits, registration of results. At the end of this research, many of these functions were not continued with the same dynamism. Alternatives to finance a replacement of the researcher were proposed, such as the collective contribution of resources, but no decision was taken.

3.2. Regulations

Regarding the regulation of the PGS, in the diagnostic phase, the market promoters expressed relevance and clarity of the definition of agroecology and principles defined by the RMABR after two years of operation. However, in the development of the committee meetings, during 2019, difficulty in appropriating the principles was evidenced, so it was suggested to condense them into a smaller number of principles to make them easier to remember and manage (plan, promote, implement, and evaluate), and clarify which ones apply to agriculture, livestock, or processing. The proposed modification to the PGS principles of the RMABR is presented below:

Transversal: they apply to all production systems (agricultural, livestock, processed) and condense the old principles 1, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 14, 18, and 19 as follows:

Specifically exclude the use of toxic agrochemicals (pesticides and chemically synthesized fertilizers) and Genetically Modified Organisms – GMOs.

Promote the proper use and conservation of water, encourage reducing polluting gases emission into the atmosphere, and implement proper management of solid waste.

Prevent diseases in plants, animals, and humans. Management should be done using environmentally friendly inputs and practices. Hygiene and sanitary safety of all products must be ensured during primary production, harvesting, and processing. Food producers should take a food handling course and update it every year.

To be managers of food sovereignty, actively participating in decisions about agricultural products’ production, distribution, and consumption. An intermediary can participate in the commercialization chain with solidarity purposes, promoting fair trade between conscious consumers and responsible producers. Advertising practices should be consistent with market principles, with transparent and reliable information.

Agricultural and livestock: they condense the old principles 2, 6, 7, and 8 as follows:

Promote soil and biodiversity conservation practices for the latter by protecting and preserving fauna and flora adapted to the environment, giving preference to native and creole species.

Support process rather than input agriculture, promoting the efficient use of local resources and reducing external inputs.

To promote animal welfare, respecting their physiological conditions and their adaptation to their environment and vice versa.

Processed: condense the old principles 11, 12, 13, 16, and 17 as follows:

For processed products to be considered organic/agroecological, at least 75% of the ingredients must be organic/agroecological when assessing the weight/volume of the final product.

Promote traditionally used processes such as dehydration, smoking, and natural additives to definitively eliminate synthetic preservatives, refined sugar, and other additives that affect human or environmental health. The use of ionizing radiation or toxic agrochemicals in post-harvest is not permitted.

Ideally, packaging and labels should be made of biodegradable or reusable materials unless there is not yet a technological solution that allows for this.

These ten principles manage to integrate, briefly, the conservation of ecosystems from the promotion of agroecological practices in technical, environmental, and socioeconomic aspects.

It is proposed that the old principles 15 and 20, described below, should be included in the certification process as requirements but should not determine the classification of production systems:

15. Each producer shall keep technical and accounting records that allow for participatory certification and support and monitor their production system.

20. Each processor and solidarity intermediary are responsible for its suppliers (raw materials and finished product, respectively) and must certify them with the same PGS.

After this research, this proposal was in the process of being evaluated by members of the PGS committee.

One change proposed by producers and immediately adopted was to clarify the definition of agroecological processed and transition products in the current principle 11, which corresponds to principle 8 of the proposal, the corrected text of which has already been presented.

3.3. Procedures

Due to the number of producers (approximately 200) and the established frequency of each visit (annual), four visits per week were required, which implies a full-time person when adding the time needed to follow up on work plans and registration, among other activities, or, failing that, that one person leads the PGS for each market, along with better coordination between markets of the RMABR. When not deciding in this sense, due to the costs it represents for the markets, it was suggested and approved that the certification frequency is increased from 12 to 18 months, seeking consistency with the operational capacity. Despite this modification, the limitation of time and workforce for the implementation of the PGS persists.

The participatory certification form was updated in three aspects: 1- inclusion of instructions for filling it out, 2- greater clarity by substituting technical terms, for example: allopathic veterinary medicines for pharmaceutical products, or adjusting the wording, 3- sufficient space for filling it out. It was also decided to add a box to the agroecological transition form that mentions whether it is a transition or improvement plan, so it is now called a ‘work plan.’

In addition, one of the RMABR member markets autonomously decided to create a Google form to upload the information from each participatory certification format, considering that it would add value by condensing the results and then extracting descriptive statistical measures.

3.4. Certification and promotion of agroecology

The certification visits made it possible to identify some difficulties producers face in achieving agroecological production, with greater progress in the agricultural transition, less in the livestock transition, and much less in processing. The 60 certification visits that were conducted identified as specific challenges of the agroecological transition: access to agroecological seeds; access to agroecological livestock; access to agroecological animal feed; improvement of animal welfare (infrastructure, management); use of alternative veterinary medicine; strengthening of soil and water conservation practices; correct production of bio-inputs; improving the design of production systems (vocation, scale/productivity, and constant supply); and in processors, supply with agroecological raw materials and use of packaging and labels consistent with agroecology.

Given these results, a theoretical-practical workshop was proposed by an expert in the selection, harvesting, conservation, and propagation of vegetable seeds, but it was not carried out because the producers did not attend. Field schools were also planned for the exchange of knowledge from producer to producer with the support of specialized personnel on topics such as agroecological animal feeding, ethnoveterinary, water and soil conservation, integrated pest and disease management (IPDM), post-harvest, and packaging; these were also not carried out for the same reason.

Another strengthening action proposed was to establish a working network between processors and primary producers so that the former can source locally produced agroecological raw materials, certified by their own PGS, to promote a solidarity economy. To this end, a diagnosis was made through the design and implementation of an exploratory survey that was answered by a total of 35 processors of the RMABR, which consisted of four closed questions and one open question, obtaining the following results:

Most of the processors surveyed produce food (74.3%), followed by cosmetics (20%), medicinal products (11.4%), personal care products (8.6%), and others (5.7%), for which they require especially raw materials of vegetable origin (97%) and, in second place, of animal origin (11.4%). Fifteen processors (43%) obtain these raw materials entirely from the trade, 17 obtain them partially (10-90%) from the trade, and only three process their raw materials. The major difficulties faced by the processors are: permanent supply of raw materials, fair price, quality, quantity, and logistics. A large proportion of the respondents are not clear whether producers in the network can supply the products they require.

3.5. Training on the functioning of the PGS

During 2018, three training days on the functioning of the PGS were developed, in which 69 individual producers and 70 associated producers of the RMABR participated; most of them, for various reasons, were not present during the construction of the PGS in 2016-2017. The objective of the training was to sensitize and prepare them for the participatory certification process.

Each day was developed in three moments: first, as a lecture, the definition and principles of agroecology were socialized, as well as the procedures of the PGS of the RMABR, with the support of a booklet designed for the producers (Chaparro Africano & Naranjo, Citation2017). In a second moment, a practical exercise was done in groups, which allowed producers to familiarize themselves with the participatory certification and work plan formats. Finally, the results of the exercise were socialized, and time was given to resolve doubts and receive suggestions regarding the regulations and procedures. The suggestions made by the producers were already described in the section on regulations.

4. Discussion

Agroecological production has important social, cultural, and political implications and environmental, economic, and productive ones. Although agroecology is attractive to some to produce safe food, in this case, and the form of a (Chaparro-Africano & Franco-Chocue, Citation2020), we agree with Bara (Citation2018) and Bouagnimbeck et al. (Citation2014). PGS contributes to the well-being of communities by increasing their education, participation, autonomy, developing fairer economic relations, weaving trust and solidarity, strengthening social processes by improving linkages, empowerment of producers, access to markets, increased income, and food sovereignty.

Moreover, Kaufmann and Vogl (Citation2018) highlight the importance of looking objectively at the challenges faced by PGS to achieve their maximum reach, rather than approaching them with a romantic view that overemphasizes their strengths. Based on the experience of the researchers and this recommendation, the discussion focuses on two aspects considered to be the main challenges for the PGS to fulfill its functions of certification and promotion of agroecology: participation for governance (Nelson et al., Citation2016), proper to the political dimension of agroecology, and some technical aspects, proper to the socio-economic and environmental dimensions, all equally important when we seek to promote agroecology (Cuéllar-Padilla & Calle-Collado, Citation2011), and strong sustainability (Daly, Citation1991).

To begin with, it is important to provide clarity when speaking of participation. Caporal (Citation1998) lists eight types of participation: manipulated, passive, through consultation, through material incentives, functional, interactive, supported, and self-mobilization, according to which the RMABR PGS would be between levels seven (participants work together, supported by third parties who respect their dynamics, but who at the request of the participants, help to overcome weaknesses, although the participants make decisions) and eight (participants do not depend on external inputs, although these can guide or provide funding as long as the participants have control of the process and resources).

On the other hand, Geilfus (Citation2002) describes seven very similar levels, organized in a ‘ladder of participation’: passive participation, information providers, consultation, incentives, functional, interactive, and self-development. If a level of participation were assigned to the PGS of the RMABR, it could be placed in interactive participation, where people influence the formulation, implementation, and evaluation of the project and progressively take control. Precisely, Cuéllar-Padilla and Calle-Collado (Citation2011) highlight that interactive participation is common in agroecology with groups that have little experience in participatory processes. Balcázar (Citation2003), on the other hand, assures that there are PRAs with high, medium, and low degrees of participation; in this context, the PGS of the RMABR is located between medium to a high level.

The challenge, then, is to move towards self-development (Geilfus, Citation2002) or self-mobilization (Caporal, Citation1998) without forcing the processes and without undervaluing the advances in participation. It must be said, in turn, that for participation to be strengthened, it should not be overwhelming, as this does not convene but rather, on the contrary, demotivates. At this point, we come to the reflection on how to structure a truly participatory and viable System of Guarantees. To achieve this, there are no recipes; it is necessary to carry out permanent action research or praxeology (Caporal, Citation1998). This approach allows reflecting on the practice or socio-praxeology to learn from it and move forward (Villasante, Citation2019) to learn from it and move forward.

Although it is taken for granted that participation has only positive aspects, this research has had nuances. On the one hand, it has enabled the creation of the RMABR and the PGS, among other achievements. On the other hand, it has not enabled it to be fully operational or more dynamic, which has led to a lack of clarity about what participation implies, which poses the task of establishing a framework for its management. In this regard, Balcázar (Citation2003) proposes variables such as control, collaboration, and commitment to categorize participation in PAR processes, while Geilfus (Citation2002) proposes considering how people participate throughout the PAR who makes the decisions. A framework proposal for analyzing and managing participation in PAR, in agroecological processes in general, and PGS in particular, is presented in and suggested to consider who, how and for what participate, basic elements to start any participatory process and to promote participation aimed at self-development.

Comparatively, Sánchez (Citation2005) proposed a three-step model to manage participation, but from the perspective of business organizations: knowing the mission, the existence of a climate of trust and participation structures, although they are only like those proposed in the ‘how’, in . A closer approximation is that of Norad (Citation2013), which proposes a framework for the analysis and evaluation of participation, more comparable to the proposal in , which also gives guidelines for manage it: category, type, who, reasons, conditions, level, and results. No more studies were identified that propose other frameworks on how to manage specific participation in social and agroecological processes, since most of the research and theoretical contributions are related to political participation, which differ by their legal framework, and to participation in business organizations, which differ by its hierarchical leadership structure, so the contribution shown in and detailed in is considered significant.

Table 1. Framework for managing participation in agroecological processes.

The details of are presented in , including three components of the proposed participation management framework, one or more variables for each component, a column with potentialities that justifies components and variables, the relevant challenges to achieve the potentialities, and the fifth and sixth columns present the results of this research by component:

Expanding on the variables of diversity and equity in , they are vital for the horizontality of relationships; to connect the processes of production, marketing, and consumption; to legitimize decisions; to share responsibilities and achievements; and to ensure that the PGS is operational and meets its objectives. Something that has generated a misconception of low participation is that many members of the RMABR have two or three roles: promoter, producer, and consumer, which is positive because it evidences solidarity economy practices and the complexity of reality while allowing to understand the other instead of judging it, enriching the process. This contrasts with the fact that the greatest participation is by those who are mainly promoters, followed by those who are mainly producers, and finally, by those who are mainly consumers, who limit themselves especially to accompanying some certification visits, which occurs in the majority of the experiences (Bouagnimbeck et al., Citation2014). However, this is positive because participation is a real possibility in the face of exclusion in conventional markets.

The role of UNIMINUTO, as the most insistent of the promoters of the RMABR and the PGS, is more complex. UNIMINUTO is a private, Catholic institution of higher education that seeks to train, research, and make a social projection, but whose representatives produce, consume and/or distribute agroecological products, which is not accidental and is not considered a conflict of interest, since it ensures a quasi-permanent commitment with minimal external dependencies, unlike the periodic, short-term interventions, especially by government entities (Hruschka, Kaufmann, & Vogl, Citation2021; Chaparro-Africano & Naranjo, Citation2020). Additionally, UNIMINUTO works as a facilitator, promoter, and dynamizer, and not as a leader, as proposed by Villasante (Citation2019), which has allowed the actions to be distributed in what he calls ‘driving groups’ (Hruschka, Kaufmann, & Vogl, The benefits and challenges of participating in Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) initiatives following institutional formalization in Chile, 2021). This has allowed the actions to be distributed in what he calls driving groups, which have allowed educating by transforming and transforming by educating. UNIMINUTO also brings technical expertise to the process. (Chiffoleau et al., Citation2019; Cuéllar, Citation2009).

Regarding dynamization, between 2016-2017, the PGS committee was composed of three representatives from eight markets, based on the hypothesis that a large committee affected the agility in decision making, this changed during this research when it became evident that it reduced diversity and equity in participation, and contrary to what was believed, it made the PGS less operational, because the information did not reach everyone fluently (Naranjo, Citation2017). This changed during this research when it became evident that it reduced diversity and equity in participation, and contrary to what was believed, it made the PGS less operative because the information did not reach everyone fluently. In any case, the participation of collectives as large and diverse as the RMABR (approximately 200 producers and 2,000 consumer families) is complex, which has been identified in other experiences (Méndez et al., Citation2017).

Time dramatically limited participation regarding the capacity to participat (Méndez et al., Citation2017). In fact, in the ‘action’ phase, the days for the exchange of knowledge and training did not take place, apparently because, despite being considered valuable, they demand time that producers, promoters, and consumers do not have, since their main destination is their production, market or personal work. Demanding more time implies overwhelming people who have already seen their spaces for personal, family, community, and leisure development undermined.

Precisely in response to time constraints, PGS experiences such as the Ecovida network in Brazil, one of the most consolidated, proposes the remuneration of participatory certification work so that people can meet their economic needs without neglecting their main source of income, which can be complemented through partnerships with technical entities (Cuéllar, Citation2009), in this case, UNIMINUTO. PGS in Latin America are predominantly financed by development projects and solidarity agencies, such as in Brazil and Mexico. However, in other cases, the lack of funding is not always enough (IFOAM, Citation2013), although in other cases, the lack of legal recognition does not motivate their funding.

It must be said that external funding is required, but it has not been desirable by some members of the RMABR, as it can determine subordination and dependence in time, purposes, and resources, which would move away from the autonomy that has characterized it. In any case, the financing of this research was not at one extreme or the other, since the external financing only included the researcher's time, since his expenses were co-financed by the markets, and sometimes by the producers or by the researcher himself. This external funding was accessed because the requirements were feasible to meet and the proposal was not thematically limited, which falls within those quasi-ideal financial alternatives, which unfortunately did not have continuity as public policy. Thanks to this financing alternative, the greatest progress of the PGS in its history was achieved because, unfortunately, some markets did not continue with the certification visits or carried them out with less dynamism once this research was completed.

In any case, it is insufficient to have one person dynamizing the operation of the PGS with external financing, if in parallel the market promoters and producers in the first place, and the consumers in the second place, do not participate, as it would be closer to being a TCO, when what is desired is not to fall into the rationality of outsourcing these processes so as not to lose the benefits of their being participatory, which has justified the commitment to PAR that encourages transformation, and which, according to Balcázar (Citation2003), provides the opportunity to ‘learn to learn.’

Some additional elements that make participation complex, by participant ability, consistent with the findings of Hruschka et al. (Citation2021), López (Citation2019), Bouagnimbeck et al. (Citation2014), and Boza (Citation2013), include:

| − | Several people are simultaneously involved in several organizations, which takes away from effective time. | ||||

| − | Conflicts between representatives, some of them towards operability and others towards idealization. | ||||

| − | Lack of training and experience for participation. | ||||

| − | Geographical distance, because although the RMABR is local (Chaparro-Africano, Citation2019), a few producers are very distant, and in any case, mobility in Colombia and Bogotá is very poor. | ||||

| − | The unproductive participation of some who compromise but do not deliver. | ||||

| − | The common understanding and ownership of the PGS, which gave little autonomy for certification and the transition to agroecology, motivated the training in this research, which should have been done when the PGS was created and repeated periodically. | ||||

Regarding the motivation for participation, Hruschka et al. (Citation2021) report that increasing prices and income was the most important motivation for belonging to a PGS, but later it became sharing knowledge and being part of a community. In this research, the motivations have been varied: for the producer, certification is a requirement to participate in these and other markets and calls for support; for the consumer, it is to know what is consumed and to know the producers; for the promoter, it is important to have coherence between what is said and what is done to generate trust, but also that their producers are sustainable; and in all cases, it has been important to create community. Having identified these motivations, which are based on the problems, needs, or expectations of the participants, is a key starting point, as it determines that the PGS obeys the needs of the participants (Cuéllar-Padilla & Calle-Collado, Citation2011). It determines that the PGS obeys a logic of autonomous and coordinated work instead of the TPC, which obeys a logic of control (Pino, Citation2017).

Complementarily, the initial motivation for the researchers, was the introspection that the producers, promoters, and consumers themselves have made about the meaning of agroecology, allowing individual and collective reflection on the productive, commercial, and consumption practice, aspects typical of the processes of participatory generation of knowledge such as action research and praxeology (Juliao, Citation2011). This reflection on practice is more valuable when it is carried out periodically, as in this case: the first cycle of PAR in 2016-2017, the second in 2018-2017, and it remains to be seen when a third cycle is required.

Regarding participation trust, it is the basis of PGS, short marketing circuits such as RMABR (Chaparro-Africano & Naranjo, Citation2020) of short marketing circuits such as RMABR (Chiffoleau et al., Citation2019), and PAR processes in general (Méndez et al., Citation2017), so it must be strengthened. Other studies (Hruschka, Kaufmann, & Vogl, The benefits and challenges of participating in Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) initiatives following institutional formalization in Chile, 2021) report certain breaches of PGS regulations by producers, which fracture trust, as in this research with cases of parallel production or noncompliance with other aspects of the regulations, although they have been marginal.

In relation to the efficiency of participation, it is in a range between very good, if one takes into account that only 6.75% of the resources with which four of the markets worked in 2016 came from external sources (Chaparro-Africano, Citation2019), that 60 visits were carried out at a low cost and with participatory funding, to regular, as some of the proposals for improvement arising from this research (2018–2019) had not been approved and/or discussed in the RMABR until May 2021.

The PGS of the RMABR is also important because of the continuity it has demonstrated, in contrast to the lack of continuity of governmental actions (Hruschka, Kaufmann, & Vogl, The benefits and challenges of participating in Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) initiatives following institutional formalization in Chile, 2021), which is a determining factor in processes whose impacts will be more evident in the long term, as stated by Stern (Citation2007). The lack of continuity of public policies is evident in the Colombian case, for example, in the 10-year gap that existed in the updating of organic production regulations between Resolution 187 of 2006 and Resolution 199 of 2016 (Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural MADR, Citation2006) and Resolution 199 of 2016 (Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural, Citation2016), but also the loss of certified hectares in organic production in the country (FiBL and IFOAM Organics International, Citation2021), and Resolution 464 of 2016 (Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural MADR, Citation2017). Although it recognizes PGS, it has been limited to characterizing experiences and not promotion (Zuluaga, Citation2018) and not promotion.

Continuity is also expressed in participation in all stages of the process: diagnosis, planning, action, and evaluation, as also claimed in other studies (González & Nigh, Citation2005; Méndez et al., Citation2017).

With respect to communication for participation, if it is assertive, it generates ownership of the PGS by all the members (Cuéllar-Padilla & Calle-Collado, Citation2011, allowing learning, increasing efficiency and effectiveness of the process, but also generates trust.

Regarding the effectiveness of the PGS, 60 producers were certified, and some aspects of the agroecological transition in their production systems were improved in environmental and economic terms, as reported by Bouagnimbeck et al. (Citation2014), although other achievements that are less obvious and are part of political agroecology should not be undervalued, such as: learning to participate; acting to address their problems, needs, and expectations without waiting for State action; the deconstruction of the conventional (Cuéllar-Padilla & Calle-Collado, Citation2011); the promotion of ethical and social ethics (Rahmann et al., Citation2017) in production, distribution, and consumption; and perhaps the most important, the search for strong sustainability, as highlighted in other (Daly, Citation1991) as highlighted in other processes (Torremocha, Citation2012).

It is proposed then that the key strategy in social processes such as this is ‘dynamic equilibrium,’ somewhat in coincidence with the proposal of Torremocha (Citation2012), not only of the variables proposed in , but of other elements, as proposed by Villasante (Citation2019), Chiffoleau et al. (Citation2019), Torremocha (Citation2012), Cuéllar-Padilla and Calle-Collado (Citation2011), and Whittingham (Citation2010):

| − | Between contradictions and coherences: being closer to a PGS than to a TCP, | ||||

| − | Between dynamic stability: novelty and permanence, learning but keeping what works well, | ||||

| − | Between planning and emergent, | ||||

| − | Between regulations and flexibility, | ||||

| − | Between the dialogue of knowledge, reflection, and action, | ||||

| − | Between the ideal and the operative, | ||||

| − | Between competition and cooperation, | ||||

| − | Between the individual and the collective, | ||||

| − | Contribute, but do not monopolize, and commit to little, but deliver, | ||||

| − | Promote the endogenous without disregarding the external, | ||||

| − | Learning and unlearning, among others, | ||||

| − | Do not rely on external funding or resources, but do not turn them down if they can help, | ||||

| − | Achieve quantitative and qualitative benefits, | ||||

After this analysis, and based on the definition of governance proposed by Whittingham (Citation2010): political relations between diverse actors that decide, execute, and evaluate matters of public interest, in processes where competition and cooperation coexist, it is concluded that this PGS is an example of governance, as other authors have already suggested (Pino, Citation2017). Therefore, managing assertive participation is key to achieving governance in the RMABR.

Regarding the second aspect to be discussed in this research, the technical challenge of the agroecological transition, the certification visits carried out identified some difficulties faced by producers in practicing agroecology, which persists compared to previous years (Chaparro-Africano & Naranjo, Citation2020; Chaparro-Africano, Citation2019) and is common to other agroecological transition processes, with greater progress in the agricultural transition, less in the livestock transition and much less in processing (Chavarría-Muñoz et al., Citation2019; Galeano, Citation2007). This is due to processing dependence on agricultural and livestock production (raw materials) and livestock production on agricultural production (animal feed). These aspects need to be analyzed in more detail and addressed more assertively in a subsequent PAR cycle.

Finally, the challenge of reducing or eliminating external inputs, the production of own inputs, and the development of production of processes rather than inputs is also highlighted. In this sense, it must be said that two currents have come together through demand and supply: from the supply side, there is the proliferation of inputs for organic agriculture; and from the demand side, there are producers who prefer to buy these inputs because they do not have family labor, they cannot get workers to hire, or because the area of their property is insufficient for the production of seeds, fertilizers, or animal feed (Chaparro & Calle, Citation2017). These are two structural problems for the agroecological transition that have been discussed elsewhere and require creativity and innovation for their solution (Chaparro, Citation2018) and require creativity and innovation for their solution, as proposed in this research, with solidarity work between primary producers and processors, so that a producer does not necessarily generate in his agroecosystem everything he needs, but can acquire it with his partners.

5. Conclusions

Apparently, the main challenge that the PGS has had to take on is the contribution of time from its members, especially consumers, less so from producers and much less from market promoters. However, after this analysis, we conclude that the real challenge is more complex and managing three components: who participates, how and why, more than time, which must be managed assertively and with ‘dynamic equilibrium’. In the ‘who’ it is suggested that diversity and equity be considered as variables; in the ‘how’ it is suggested to manage the capacity, motivation, confidence, efficiency, continuity, communication, and procedures; in the ‘for what’ it is suggested that effectiveness be considered.

The PGS of the RMABR is an example of governance, and assertive participation is fundamental to improve governance in the RMABR, which will in turn influence the RMABR to achieve its purpose of contributing to the construction of sustainable agri-food systems.

Technical challenges persist in the agroecological transition, the greatest in processing, less in livestock production, and much less in agricultural production. In general, the need to reduce dependence on external inputs persists, although there are structural limitations to achieve this, and networking is suggested to overcome it.

In future publications we hope to share results regarding the implementation of the participatory management framework in agroecological processes, to contribute to the sustainability of PGS and other social innovations.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the members of the Red de Mercados Agroecológicos de Bogotá Región for participating and believing in this process. Thanks to the Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios UNIMINUTO, Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje SENA, and Colciencias for funding this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adriana-María Chaparro-Africano

Adriana-María Chaparro-Africano is Professor at Agroecological Engineering, Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios UNIMINUTO. She did Ph.D. in Agroecology from the Córdoba University, Spain in 2014 and is associated with UNIMINUTO since 2011. She is author of many research and review articles published in high impact journals. Her research and publications focus especially on agroecological markets, participatory guarantee systems, and everything related to agroecological production, agroecological transition, and sustainable consumption.

Miguel Páramo

Miguel Páramo is an Agroecology engineer from the Corporacion Universitaria Minuto de Dios UNIMINUTO. He did a specialization in Family farming at UNIMINUTO in 2022 and has been working with family farmers since 2021.

References

- Balcázar, F. (2003). La investigación-acción participativa en la psicología comunitaria: Principios y retos. Apuntes de Psicología, Vol. 21(No. 3), 419–435.

- Bara, C. (2018). Implicaciones y viabilidad de la certificación Orgánica participativa como instrumento para promover La Producción Orgánica y Los Mercados Locales En San luis De potosí (tesis doctoral). Repositorio Institucional de la UASLP.

- Binder, N., & Vogl, C. (2018). Participatory Guarantee Systems in Peru: Two case studies in Lima and apurímac and the role of capacity building in the food chain. Sustainability, 10(12), 4644–421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124644

- Bouagnimbeck, H., Ugas, R., & Villanueva, J. (2014). Preliminary results of the global comparative study on interactions between PGS and social processes. Proceedings of the 4th ISOFAR scientific conference. ‘Building organic bridges’, at the Organic World Congress 2014, 13-15 Oct. (pp. 435-438). istanbul,: ISOFAR.

- Boza, S. (2013). Los sistemas participativos de garantía en el fomento de los Mercados locales de productos orgánicos. Polis, Revista Latinoamericana, Volumen 12(N 34), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682013000100002

- Caporal, F. (1998). La extensión agraria del sector público ante los desafíos del desarrollo sostenible: El caso de Rio Grande do Sul, brasil. Universidad de Córdoba.

- Cavallet, L., Canavari, M., & Fortes Neto, P. (2018, Agosto 09). Participatory guarantee system, equivalence and quality control in a comparative study on organic certifications systems in Europe and Brazil. https://doi.org/10.4136/ambi-agua.2213

- Chaparro, A. (2018). Recampesinización y agroecología para la sostenibilidad de los sistemas agroalimentarios. In J. P. Molina, A. Lesmes, A. Parrado, A. Chaparro, M. Franco, A. G. Gómez, & A. Mora-Motta (Eds.), Desafíos para la implementación de políticas públicas de desarrollo rural territorial en Colombia (pp. 463). Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Chaparro, A., & Calle, A. (2017). Peasant economy sustainability in peasant markets, colombia. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, Volume 41, (Issue 2), 204–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2016.1266069

- Chaparro-Africano, A. (2019). Toward generating sustainability indicators for agroecological markets. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 43(Issue 1), 40–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2019.1566192

- Chaparro-Africano, A., & Naranjo, S. (2020). Participatory system of guarantees – PSG of the Red de Mercados Agroecológicos de Bogotá Región RMABR. A contribution to the sustainability of agroecological producers and markets. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 18(Issue 6), 456–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1793614

- Chaparro-Africano, A. M., & Franco-Chocue, L. M. (2020). Costos de producción de productos agroecológicos, en productores familiares de pequeña escala, de la feria agroecológica UNIMINUTO, colombia. Cooperativismo & Desarrollo, 28(117), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.16925/2382-4220.2020.01.07

- Chaparro Africano, A. M., & Naranjo, S. (2017). Red de Mercados Agroecológicos de Bogotá Región. https://redmercadosagroecologicosbogota.co/wp-content/uploads/PDF/Cartilla_agroecologica_v8.pdf

- Chavarría-Muñoz, K., Tapiero-Calderón, M. A., & Chaparro-Africano, A. M. (2019). Construcción de un sistema participativo de garantía con y para la ARAC (asociación Red agroecológica campesina) en el municipio de subachoque, cundinamarca, en 2015. Revista Luna Azul (On Line), 49, 64–89. https://doi.org/10.17151/luaz.2019.49.4

- Chiffoleau, Y., Millet-Amrani, S., Rossi, A., Rivera-Ferre, M., & Lopez Merino, P. (2019). The participatory construction of new economic models in short food supply chains. Journal of Rural Studies, 68, 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.019

- Clark, P., & Martínez, L. (2016). Local alternatives to private agricultural certification in Ecuador: Broadening access to ‘new markets’? Journal of Rural Studies, 45, 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.01.014

- Cuéllar, M. (2009). Hacia un Sistema Participativo de Garantía para La Producción ecológica en andalucía (tesis doctoral). Universidad de Córdoba.

- Cuéllar-Padilla, M., & Calle-Collado, A. (2011). Can we find solutions with people? Participatory action research with small organic producers in andalusia. Journal of Rural Studies, 27(4), 372–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.08.004

- Cuéllar Padilla, M., & Ganuza Fernández, E. (2018). We don’t want to Be officially certified! reasons and implications of the Participatory Guarantee systems. Sustainability, 10(4), 1142–1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041142

- Daly, H. (1991). Elements of environmental macroeconomics. In R. Constanza (Ed.), Ecological economics: The science and management of sustainability (pp. 32–46). Columbia University Press.

- FiBL and IFOAM Organics International. (2021). The world of organic agriculture. Statistics and emerging trends 2021. Suiza: FiBL and IFOAM Organics International.

- FiBL; IFOAM. (2021). The world of organic agriculture, statistics & emerging trends 2021. Suiza: FiBL and IFOAM Organics International.

- Fonacier Montefrio, M., & Taylor Johnson, A. (2019). Politics in participatory guarantee systems for organic food production. Journal of Rural Studies, 65, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.014

- Fouilleux, E., & Loconto, A. (2017). Voluntary standards, certification, and accreditation in the global organic agriculture field: A tripartite model of techno-politics. Agriculture and Human Values, 34(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9686-3

- Galeano, A. (2007). Estado actual y retos de la agroecología en el contexto de la política agraria colombiana. I Congreso científico latinoamericano de agroecología, Rionegro, Antioquia, 13-15 de Agosto de 2007.

- Geilfus, F. (2002). 80 herramientas para el desarrollo participativo. IICA.

- González, A., & Nigh, R. (2005). Smallholder participation and certification of organic farm products in Mexico. Journal of Rural Studies, 21(Issue 4), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.08.004

- Hatanaka, M., Bain, C., & Busch, L. (2005). Third-party certification in the global agrifood system. Food Policy, 30(Issue 3), 354–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2005.05.006

- Hruschka, N., Kaufmann, S., & Vogl, C. (2021). The benefits and challenges of participating in Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) initiatives following institutional formalization in Chile. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 393–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.1934364

- IFOAM. (2008). Sistemas Participativos de Garantía Estudios de caso de India, Nueva Zelandia, Brasil, Estados Unidos, Francia. Alemania: IFOAM.

- IFOAM. (2013). Sistemas Participativos de garantía. Estudios de caso en américa latina. Brasil, Colombia, México y Perú. Alemania: IFOAM.

- Juliao, C. (2011). El enfoque praxeológico. Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios - UNIMINUTO.

- Källander, I. (2008). Participatory guarantee systems–PGS. Swedish Society for Nature Conservation.

- Kaufmann, S., & Vogl, C. (2018). Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) in Mexico: A theoretic ideal or everyday practice? Agriculture and Human Values, 35(2), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-017-9844-2

- Loconto, A., & Hatanaka, M. (2017). Participatory Guarantee Systems: alternative ways of defining, measuring, and assessing ‘sustainability’. Sociologia Ruralis, 58(2), 412–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12187

- López, J. (2019). Análisis de la implementación del Sistema Participativo de Garantía para fomentar la Producción Agroecológica en el cantón cayambe. Trabajo de titulación. Universidad Central del Ecuador Facultad de Ciencias Agrícolas Ingeniería Agronómica.

- López Cifuentes, M., Vogl, C., & Cuéllar Padilla, M. (2018). Participatory Guarantee Systems in Spain: Motivations, achievements, challenges and opportunities for improvement based on three case studies. Sustainability, 10(11), 4081–4272. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114081

- Méndez, E., Caswell, M., Gliessman, S., & Cohen, R. (2017). Integrating agroecology and Participatory Action research (PAR): lessons from Central America. Sustainability, 9(705), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050705,

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. (2016). Resolución 199 de 2016. MADR.

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural MADR. (2006). Resolución 187. Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural MADR.

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural MADR. (2017). Resolución 464 de 2017. MADR.

- Naranjo, S. (2017). Hacia la implementación de un sistema participativo de garantías en la Red de Mercados Agroecológicos de bogotá - región. (Trabajo de grado). Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios.

- Nelson, E., Gómez, L., Schwentesius, R., & Gómez, M. (2010). Participatory organic certification in Mexico: An alternative approach to maintaining the integrity of the organic label. Agriculture and Human Values, 27(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9205-x

- Nelson, E., Gómez Tovar, L., Gueguen, E., Humphries, S., Landman, K., & Schwentesius Rindermann, R. (2016). Participatory guarantee systems and the re-imagining of Mexico’s organic sector. Agriculture and Human Values, 33(2), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9615-x

- Nigh, R., & González Cabañas, A. (2005). Smallholder participation and certification of organic farm products in mexico. Journal of Rural Studies, 21(Issue 4), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.08.004

- Norad. (2013). A framework for analysing participation in development. Norad - Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

- Padel, S. (2010). The European regulatory framework and its implementation in influencing organic inspection and certification systems in the EU. Reino Unido.

- Pino, M. (2017). Los sistemas participativos de garantía en el Ecuador. Aproximaciones a su desarrollo. Letras Verdes. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Socioambientales, 22(22), 120–145. https://doi.org/10.17141/letrasverdes.22.2017.2679

- Rahmann, G., Andres, C., Yadav, A., Ardakani, M., Babalad, H., Devakumar, N., & Soto, G. a. (2017). Innovative research for organic 3.0 volume 2. Proceedings of the scientfc track. Organic World Congress – Vol-II, November 9-11 10.3220/REP1510908963000 (p. 322). Delhi: Johann heinrich von thünen-institut.

- Raynolds, L. (2004). The globalization of organic agro-food networks. World Development, 32(Issue 5), 725–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.11.008

- Sacchi, G., Caputo, V., & NaygaJrR. (2015). Alternative labeling programs and purchasing behavior toward organic foods: The case of the Participatory Guarantee Systems in Brazil. Sustainability, 7(6), 7397–7416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7067397

- Sánchez, M.. (2005). Modelo para la gestión de la participación en las organizaciones. Investigación y relaciones públicas: I Congreso Internacional de relaciones públicas, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, November 17 and 18, 2004.

- Stern, N. (2007). Stern review: La economía del cambio climático. HM Treasury.

- Torremocha, E. (2012). Los sistemas participativos de garantía. Herramienta de definición de estrategias agroecológicas. Agroecología, Vol. 6, 89–96.

- Velleda Caldas, N., Anjos, F., & Lozano, C. (2014). Obstáculos hacia la implantación de un sistema participativo de garantía en andalucía. Revista Iberoamericana de Economía Ecológica, Vol. 22, 53–68.

- Villasante, T. (2019). Algunas distinciones, fracasos y transducciones co-productivas. In P. Paño, R. Rébola, & M. Suárez (Eds.), Procesos y metodologías participativas. Reflexiones y experiencias para la transformación social (pp. 18–41). CLACSO-UDELAR. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvtxw3sz

- Vogl, C., Kilcher, L., & Schmidt, H. (2005). Are standards and regulations of organic farming moving away from small farmers’ knowledge? Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 26(Issue 1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1300/J064v26n01_03

- Whittingham, M. (2010). ¿Qué es la gobernanza y para qué sirve? Revista Análisis Internacional, Número 2, 219–236.

- Zuluaga, J. (2018, Agosto). Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. https://www.minagricultura.gov.co/planeacion-controlgestion/Gestin/PLANEACION/Informes_de_Empalme/Informe%20Ministro%20ZuluagaFinal.docx