ABSTRACT

In order to bridge the knowledge-gap between sustainability awareness and the old world winegrowing culture, this research explores and analyses perceptions of key individuals in Portuguese wine industry regarding sustainability issues, uncovering intercultural trends, expectations and tensions. A grounded theory approach was used on collected nationwide data from semi-structured interviews with leading wine specialists. After conducting an inductive qualitative-content analysis using IRAMUTEQ software, results displayed key domains of concern rooted into three lexical macro ramifications analogous to the environmental-social-governance factors. The sector’s tendency to approach sustainability based on different strategies of action was also exposed. These are the fuse of two main strategic profiles: impact assessment versus value creation; with external exposure versus inward orientation approach. Findings may be used as a reference to wine managers and policy-makers pursuing sustainability goals. The development of a sustainability framework with guidelines is also recommended for standardized accounting and valuation principles in line with the Portuguese context.

1. Introduction

Extreme weather events and rising temperatures are impacting the viability of renowned wine regions and their wine quality (Fraga et al., Citation2015; Jones & Alves, Citation2012). Additionally, new consumption and trade trends show increasing market demand for sustainably produced wine (Baiano, Citation2021; Tait et al., Citation2019; Troiano et al., Citation2020). The wine world is changing while confronting real threatening challenges.

Even though numerous efforts have been devoted towards sustainability, this topic is still largely unexplored by the wine sector in comparison to other industries (Ferrara & Feo, Citation2018). Only in 2004, the International Organisation of Vine and Wine managed to apply the definition and general principles of sustainable development given by the Brundtland report of 1987 to vitiviniculture (OIV, Citation2004). This initial absence of a common definition of sustainable vitiviniculture, and the prevailing lack of theoretical frameworks to achieve sustainability have been perceived as a major drawback for the wine industry.

The development and incorporation of sustainability initiatives by the global wine sector are therefore seen as critical. In particular, amongst the old world winegrowing culture as its implementation has been sluggish despite the European Union being the world-leading producer of wine. In 2020, EU accounted for 45% of global winegrowing areas, 64% of production and 48% of consumption (OIV, Citation2021). Wine is also the largest EU agri-food sector in terms of exports (7.6% of agri-food value exported in 2020), placing wine grape growing as one of the most economically valuable fruit crop in the world. As for Portugal, even though a small country it ranks fourth in the EU area under vines after Spain, France and Italy, and ninth in the world. Portugal is also the fifth largest wine producer in the EU and eleventh largest in the world (OIV, Citation2021). Portuguese wine exports have been growing consistently at an average of 3.3% a year in value. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Portuguese wine exports managed to grow as much as 4.5% in value, with 2021 exports showing a growth of 8.6% in value compared to 2020 (IVV, Citation2022). Therefore, the wine sector plays a key role in the economic, social and environmental sustainability of rural societies, supporting its current urge of looking for better ways to improve sustainability performance (Keichinger & Thiollet-Scholtus, Citation2017).

Nevertheless, several knowledge-gaps still prevail. Regardless the overall consensus on the need to achieve an equilibrium among environmental, social and economic dimensions, the main challenge is when we have to weigh up, trade-off or agree over different sustainability targets (Anzivino et al., Citation2021). Not only it obliges to assess or choose between highly variable values, but the perception of sustainability per se is also very subjective, generally embedded in ideologies or attached to personal beliefs, cultural backgrounds or political views (Santiago-Brown et al., Citation2014b). The concept of sustainability becomes even less clear when applied to winegrowing systems for its complexity (Baiano, Citation2021).

Moreover, besides most of sustainability assessments being environmentally focused, non-context-comprehensive or unfit to evaluate permanent crops such as viticulture (Flores, Citation2018; Merli et al., Citation2018; Trigo et al., Citation2022), research of this nature is often too narrow and solely focused on few case studies. Sustainability initiatives have also been mainly implemented by the new world as sustainable environmental practices are a prerequisite to enter attractive wine export markets (Moggi et al., Citation2020).

In fact, very little is actually known or studied regarding sustainability within the Portuguese wine industry, particularly outside the environmental impact-spec (Costa et al., Citation2020; Matos & Pirra, Citation2020; Santos et al., Citation2020). Thus, better information, quality data and suitable methodologies to assess sustainability of the entire production process are still needed for the overall wine sector, but in particular to the Portuguese wine industry.

This study was therefore designed to develop theory from quality data by comparing different analytic discourses. It focuses mostly on the contextual dimension and discourse’s interactions amongst multi-actors of the Portuguese wine industry. The aim is to understand the dynamics and recognize conflicting elements, while identifying in which extent the perceptions of upper echelon individuals are aligned with each other in terms of sustainability meaning, practices, beliefs and concerns. For its complexity, a grounded theory approach was used when scrutinizing qualitative data collected from semi-structured interviews. This approach has been used in previous studies of this nature, such as in Flint et al. (Citation2011) and González-Esquivel et al. (Citation2020).

Thus, realizing the significance of the wine sector to Portugal’s economy and rural society, current challenges and sustainability knowledge-gaps, we inspired to conduct this study setting three objectives: (i) to capture participants’ viewpoint on sustainability meaning; (ii) provide information of their awareness on such topic by establishing a baseline understanding of already implemented sustainability practices and major issues of concern; (iii) identify potential tensions and paradoxes at different managerial levels of the wine sector. The higher purpose is to present a foundation for further research and help developing strategies for the wine sector towards sustainability goals.

This work provides several contributions to the literature. Not only addresses potential perspective-paradoxes, tensions and trade-offs regarding sustainability issues, but also provides a data-scarce nationwide view of the Portuguese wine sector. Reported findings may also be helpful to wine managers and decision-makers for the design of context-comprehensive policies and guidelines.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the state of sustainability within the wine industry, from primary sustainability initiatives to new and evolving corporate management approaches. Section 3 describes the methodology used for data gathering and analysis. Section 4 presents clustering results followed by the discussion and interpretation of classes in the next section. Section 6 finalizes with conclusion and recommendations.

2. Corporate sustainability in wine businesses: moving from awareness to action

2.1. State of sustainability in the wine industry

Portugal with a long-established history of wine production is one of the acclaimed old world wine countries. The wine sector is highly meaningful for the Portuguese socio-economic landscape (Faria et al., Citation2020). It is closely associated to the national cultural heritage and traditions, while also responsible for local economic growth, job creation and other social effects in rural areas (Fragoso & Figueira, Citation2021). There are 14 wine regions in Portugal with significant spatial and climate variability, despite Mediterranean climate conditions prevail with warm and dry summers. As by overall Mediterranean regions, severe impacts of climate change are expected, namely warmer and dryer scenarios (Fraga et al., Citation2015; Jones & Alves, Citation2012).

The wine industry’s strong susceptibility to climate change impacts has been one major catalyst for its increasing sustainability awareness. Along with the fact that today the industry is being held accountable for environmental affairs and negative impacts either on the ecosystem or surrounding communities (Flores, Citation2018). Thus, whether to cope with climate change impacts, market pressures, new environmental policies or less available inputs, sustainability initiatives have been pragmatically addressed and implemented by the sector since the early 1990s.

The Lodi Winegrape Commission is considered the pioneer. After launching in 1992 an integrated pest management programme for California winegrowers, several guidelines for sustainable wine grape growing and wine production have been developed by institutions or organizations around the world (Santiago-Brown et al., Citation2014a; Silverman et al., Citation2005).

In Portugal, there is one example of a successful regional wine sustainability initiative, the Wines of Alentejo Sustainability Programme. WASP was launched in 2015 by the Alentejo Regional Wine Growing Commission in Portugal. It was developed in collaboration with the University of Évora to create a set of guidelines supporting winegrowers from the region to produce wine in a more sustainable way. WASP is a free and voluntary programme and today, its associate members represent more than 42% of the Alentejo vineyard area (WASP, Citation2021).

Institutional pressure is another main stimulus for the development of such initiatives, including a demand for policy compliance (Pomarici & Vecchio, Citation2019). On top of that, media pressure, retailers’ concerns and specific export market’s requests are in many ways playing a decisive role on the industry’s commitment towards sustainability (Corbo et al., Citation2014; Merli et al., Citation2018). The academic body has too showed greater involvement on this matter for the expanding number of research publications on sustainable winegrowing in the last five years (Baiano, Citation2021).

Attention is likewise being claimed throughout the entire supply chain as businesses are starting to pay attention in seeking-for or carrying-out sustainable practices from wine production to distribution and consumption (Anzivino et al., Citation2021; Fragoso & Figueira, Citation2021; Neto et al., Citation2013). In fact, recent discussions have been held around a new and evolving corporate management paradigm that although still acknowledging the business’ need for profitability, also gives greater emphasis on other sustainability performance elements. Corporate sustainability mostly differentiates from the traditional growth and profit-maximization model previously adopted by companies, by recognizing accountability as necessary when committing to corporate social responsibility and sustainable development principles, namely environmental protection, social justice and equity, and economic development (Anzivino et al., Citation2021).

2.2. Going beyond business-as-usual: the need for a new systems approach

Regardless today a more sustainable approach is perceived as an essentiality by the wine industry, either to adapt to climate change or handle new export market pressures, there is still a clear reluctance regarding such transition (Baiano, Citation2021; Keichinger & Thiollet-Scholtus, Citation2017). Despite further action has increased through the development of several sustainability initiatives and certification schemes, the reality is that we are still presented with poor transparency, lack of standardization and agreement among interested parties (Ferrara & Feo, Citation2018; Flores, Citation2018; Vázquez-Rowe et al., Citation2013).

Simply trying to identify what sustainable wine production means seems to be already tortuous (Santiago-Brown et al., Citation2014b). From the universal theory of the triple bottom line where people, planet and profit are the three fundamental principles of sustainability (Elkington, Citation1994), to the description provided by OIV (Citation2004) for sustainable viticulture, no single definition has been widely accepted until this present (Corbo et al., Citation2014; Santiago-Brown et al., Citation2014b).

Winegrowing systems are as well utterly complex for being inherently linked to surrounding contexts. Its dynamic nature also suggests that any appraisal must guarantee that the context where the winegrowing system operates is always considered (Santiago-Brown et al., Citation2014a). Winegrowing systems have for that matter been described as a multi-actor service ecosystem characterized by different elements, behaviours, synergies and interactions (Anzivino et al., Citation2021).

Nevertheless, as shareholders or other stakeholders continue to reinforce and support companies committing towards sustainability, such is becoming a fundamental competitive factor for enabling more efficient financial markets (Ofstehage & Nehring, Citation2021). Any organization acting today in accordance with ESG standards by integrating social, environmental and governance factors in their business model, may be perceived by their stakeholders (or investors) as an enterprise more competitive. ESG is currently an indication of solidity, lower costs, better reputation and greater resilience to uncertainties (Godelnik, Citation2021). Thus, corporate sustainability is a multi-level notion that requires firms to address economic, environmental and social issues while attending different requests in order to reach connected and interdependent societal objectives (Anzivino et al., Citation2021).

In other words, enterprises to become sustainable must create value that relies not only on the external resources, but also on its own endogenous ability to do so. As identified in Trigo et al. (Citation2021), fundamental principles such as integrated management, dynamic balance, regenerative design and social development request for a better use and integration of available natural and human resources, in order to promote sustainable agribusinesses.

Yet, some companies continue to hold a business-as-usual approach towards sustainability as slow and cautious steps have been taken when committing to adopt more sustainable practices. Businesses concerns have been mostly focused on operational, financial and reputational risks, rather on their impact on the society and the environment overall. As coined by Godelnik (Citation2021), this ‘sustainability-as-usual’ approach is only producing a minimal and insufficient change in the world.

Also, it has been claimed that besides advertizing new and more sophisticated terms like CSR, ESG factors or carbon-neutral, the corporate culture must be stimulated to change their approach and focus on delivering more than just financial targets (Adams, Citation2015). To meet goals as measures of effectiveness without considering long-term sustainability and progress is rather a simplistic approach.

The interconnectedness of wine companies with their surrounding environments must be recognized. The systems theory approach, or open-systems approach as it describes organizations as open social systems that must interact with their environments in order to survive, was developed as a reaction to the limitations of this goal-attainment perspective (Katz & Kahn, Citation1966; Von Bertalanffy, Citation1950). The systems theory approach focus on the way elements are organized in the system and how they interact. It recognizes the parts as not static but rather dynamic and fluid (Montaigne & Coelho, Citation2012).

Wine businesses being open social systems and service ecosystems therefore means these are not only inherently connected to external conditions of the surrounding environment for essential resources. They also interact and create relationships with their suppliers, customers, employees, stakeholders and governments (Anzivino et al., Citation2021; Montaigne & Coelho, Citation2012).

Considering such complexity regarding winegrowing systems and its focal interactions with the surrounding resources, we seek to better understand this dynamics of the wine sector by capturing multi-actors’ perceptions and analysing how these interact or relate. Due to the lack of quality data and suitable theoretical frameworks for the wine industry, captured discourses were collectively scrutinized to develop hypotheses around characteristics that may arise when discussing the sustainability of the sector. The goal is to capture participants’ viewpoint on sustainability meaning; identify major issues of concern; and spot potential tensions when aiming towards different sustainability targets.

3. Material and methods

3.1. Research setting

In order to draw an overall picture of the wine sector’s perspectives on such complex topic as sustainability, this study followed a qualitative research methodology based on a grounded theory approach due to its ability to facilitate the discovery of theory from data (Dunne, Citation2011; Flint et al., Citation2011; Mcghee et al., Citation2007). It is an inductive–deductive interplay where the research begins not with a hypothesis but with a particular situation. In this case, little is currently known or studied regarding sustainability on a contextual-basis of the Portuguese wine industry (Costa et al., Citation2020; Matos & Pirra, Citation2020; Santos et al., Citation2020).

Being grounded theory a qualitative methodological approach explicitly used to develop empirically derived theory and therefore totally linked to theoretical sampling (Vasileiou et al., Citation2018), several in-depth interviews were conducted from March to July 2021 with upper echelon individuals from the Portuguese wine industry until saturation was achieved. The study was designed in order to develop theory from data by comparing different analytic discourse classes as these emerge from content analysis (Dunne, Citation2011).

A non-probabilistic sampling approach was applied as key decision-makers were purposefully selected for this work (Patton, Citation2002). To identify and contact suitable individuals, the selection criteria were based on the type of entity they work for, their current role, previous experience in the wine industry, and their ability to speak and understand Portuguese or English. A total of 80 invitation-emails were sent with 33 positive answers agreeing to schedule an interview. Recruited participants altered from top-level managers (such as presidents and executive directors from regional winegrowing commissions, inter-professional associations or wine cooperatives), to technical operation’ managers and department’s leaders in charge of planning, coordinating and executing technical components of an assignment (such as operations officers, head winemakers, vineyard managers, or even professionals with an academic background). The study’s sample comprised 33 face-to-face interview sessions (see ).

Table 1. Interviews’ profile summary table.

Social economy enterprises encompass a variety of businesses, organizations and different legal entities sharing the objective of systematically producing a positive impact on local communities and pursuing a social cause. For this study, 12 different entities were categorized as social economy organizations, including non-profit organizations, cooperative federations, mutual societies, winegrowers associations, regional commissions and inter-professional social enterprises. In summary, from wine grape growers (2) to wine companies (11) or wine cooperatives (3), R&I&D institutions and organizations (5) were involved, as well as experts from academia, research centres and consulting firms. Regional winegrowing commissions (5) and several other non-profit wine business organizations such as winegrowers associations (3), inter-professional associations (1), corporate institutions (1) and cooperative federations (2) were also included. The goal was to engage experts that could speak to their own experiences as well as to the wine industry as a whole. Participants’ identity and professional information were coded to preserve the confidentiality agreement, but in the overall a third of the participants were female and two-thirds male. The average age of the group was 49 years.

Choosing a suitable sample size in qualitative research is still a conceptual debate as several qualitative research experts continue to argue that there is no right number. Despite often recommended that the size of purposive samples should be established inductively until ‘theoretical saturation’ occurs, as no new information is being observed in gathered data (Patton, Citation2002), the very few sources providing guidelines of actual sample sizes for grounded theory studies based on interviews tend to commend between 20 and 50 participants (Bryman, Citation2012; Dunne, Citation2011). However, it must be bared in mind that the notion of saturation originates in grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1999), and in this scope saturation explicitly concerns the theoretical categories (or emerging theories) that are being developed upon data analysis. Thus, sample size in grounded theory generally cannot be determined a priori (Vasileiou et al., Citation2018).

The size of our purposive sample is therefore considered adequate and the array of wine entities and organizations included in the study adds to the capacity of seeing things as they are. Moreover, the research stream intended to spot preconceptions and identify major patterns as the sample covered 9 of the 14 different wine regions of Portugal recognized with protected geographical indications: Vinho Verde (PGI Minho), Douro/Porto (PGI Duriense), Távora-Varosa (PGI Terras de Cister), Dão (PGI Terras do Dão), Bairrada (PGI Beira Atlântico), Lisboa (PGI Lisboa), Tejo (PGI Tejo), Península de Setúbal (PGI Península de Setúbal) and Alentejo (PGI Alentejano).

All interview sessions were managed according to a dialogue script in order to assure key themes were going to be discussed and that the meeting temporal length didn’t transcend established time limit. According to our research objectives, data collection was carried out through semi-structured interviews including 10 open questions organized into three main aspects: (i) sustainability meaning, principles or values that the respondent associates to the concept of producing wine sustainably; (ii) major sustainability issues regarding the impact of winegrowing activities in terms of social, economic and environmental matters; and (iii) particularities or risks associated to a specific territory’s capacity to sustain and build resilience considering referred concerns. At the end of each session, and based on remarks from other works (Keichinger & Thiollet-Scholtus, Citation2017; Merli et al., Citation2018; Olde et al., Citation2016), ranking questions were also used. Respondents were asked to rank specific sustainability assessment components to understand their preferences regarding sustainability dimensions (environment, social, economic and governance) and scale-levels of measurement (field, estate, regional or national level).

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, interviews were conducted online using Teams (version 1.4.00.16575) and lasted on average one hour each. Meetings were in Portuguese and recorded with the permission of the interviewees, as this platform allows to capture video and audio that is safely saved directly to the cloud. Additional notes were taken during the sessions and then checked in parallel while transcribing to support the comprehension of the speech.

3.2. Data analysis

For content analysis, we used Excel and IRAMUTEQ (version 0.7 alpha 2), a software programme appropriate for qualitative textual data analysis (Avelar et al., Citation2019; Ramos et al., Citation2019). Collected information (+2000 min of session-recordings) was first transcribed verbatim using oTranscribe (version 1.1), followed by the delineation of the text corpora according to the requirements and possibilities of IRAMUTEQ software. A total of 181 pages of single-spaced transcribed text was then organized in separating sets of text by a specific command line. Each set corresponded to one interview, and the command line is text interface in the form of major features (or variables). For this study, we coded each set of text regarding: the wine region (*reg); the type of organization or entity (*ent); interviewee role or job position (*job); gender (*sex); and age category (*age).

The initial data analysis comprised a total lexicon set of 122,841 words, with 8461 distinct and 3946 of single occurrence. This first analysis of the corpus in IRAMUTEQ was made up of 3379 text segments, which are the context units created automatically by the software (Ramos et al., Citation2019). Afterwards, different analytical tests from simple to multivariate were executed using IRAMUTEQ: (i) classical textual statistics to identify frequency of words, single words (hapax coefficient), grammatical classes and root-based words (stemming); (ii) search for group specifications and factorial correspondence analysis; (iii) cluster analysis through Reinert’s method using descending hierarchical classification; and finally (iv) analyses of similarity.

In short, after coding the initial corpus into TSs by the software, our analytical act can be described into three main steps: performing a DHC and the consequent FCA to generate distinct clusters (step 1); step 2 is the characterization of each cluster based on their factorial representation and significant vocabulary (p < .0001) with greater chi-square values (χ2 > 3.84); and at last, the whole context of high-scored TSs based on FCA results of forms (words) or variables (features) was considered, and compared with results from analyses of similarity (step 3). All statistic and clustering results are presented in the following section, followed by their interpretation on the theoretical meaning of each class of discourse exposed (emerging theoretical categories).

4. Results

For the DHC analysis, corpus processing was performed in 46s, presented 4823 active forms and 229 supplementary forms, with an average of 36 words per TS. The retention of the total corpus used by the software was 92.68% (3127 of the 3374 TSs) thus considered acceptable for being higher than the required minimum retention of 70% (Camargo & Justo, Citation2013).

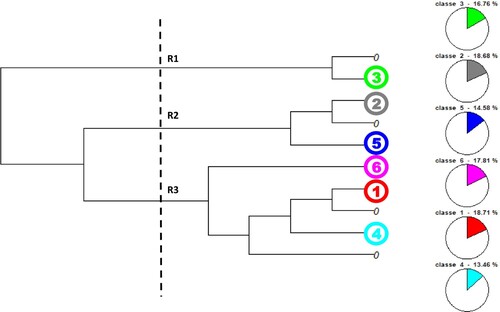

shows the six final clusters generated and their interrelations. This global DHC dendrogram tree provides the evidence that the stabilization of the clusters occurs after three macro ramifications. Ramification R1 only generates cluster 3 clearly separated from the others, with 524 TSs (16.76%). Ramification R2 leads to cluster 5 with 456 TSs (14.58%) and after another division to cluster 2 with 584 TSs (18.68%). A third moment originates ramification R3 with two distinct sections. While the first merely evolves into cluster 6 with 557 TSs (17.81%), the second section after several sub-divisions generates cluster 4 with 421 TSs (13.46%) and cluster 1 with 585 TSs (18.71%).

Figure 1. Global descending hierarchical classification of class constructs. Dendrogram tree showing the stabilization of six clusters.

Cluster 2 and cluster 5 demonstrate highest affinity with each other (R2 represents 33.36% of the total corpus). Cluster 3 is the one farther away, exhibiting either fewer relationships between the words in the context of the clusters or a clear distinction between lexical content. From these three distinct pathways created, and despite 10 distant areas of discourse were displayed, only the identified six clusters were sufficient strong to be considered a single class from this analysis.

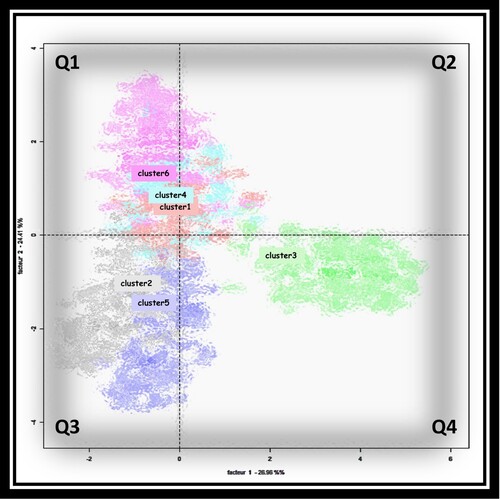

Still in step 1, from this DHC analysis, a FCA is also achieved so both can be interpreted together and discourses linked into variables. In , we have all the identified clusters presented in a Cartesian plane. As shown, cluster 3 is visibly more isolated in the bottom-right quadrant (Q4). However, it can also be perceived that cluster 6 despite initially separated from cluster 1 and cluster 4 when R3 is formed, its factorial representation confirms its proximity by sharing the same quadrant (Q1). Thus, these three clusters in Q1 represent 49.98% of the total corpus sharing closer relationships between the words or variables comparing to any of the other groups located in the two lowest quadrants (Q3 and Q4). The relationship of clusters 1, cluster 4 and cluster 6 is therefore confirmed by their approximation on the top-left quadrant over the horizontal axis, demonstrating some homogeneity in the representations between these three classes and considerable distance from the others.

On the other hand, some kind of relationship between cluster 2 and 5 to cluster 3 is also shown by remaining in the lowest-quadrants over the horizontal axis, despite the already mentioned solid isolation of cluster 3 in Q4 and its explicit separation from the other clusters over the vertical axis.

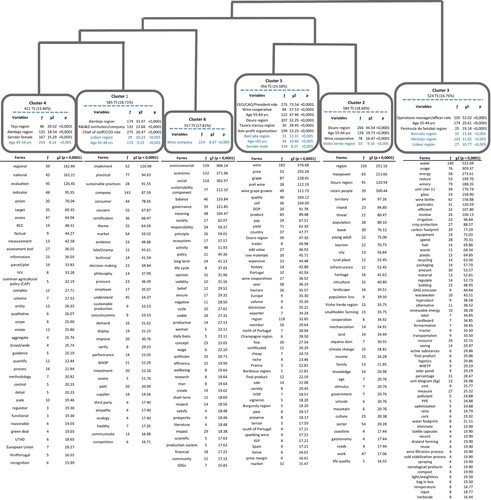

In order to better understand all relationships and connections between clusters, the intensity and importance of each term were looked in context while associated strength between words was also compared (step 2). In , each cluster’s keywords (or distinct forms) considered statistically significant (with χ2 > 3.84 and p < .0001) are displayed. The visualization of the main words with similar vocabulary between each class is complemented with their frequency per class (ƒ). Additionally, stronger variables supporting the establishment of each cluster (p < .005) were also included allowing to interpret which factors can best explain the variability of discourse and lexical content of each class.

Figure 3. Dendrogram showing the profile of each cluster and key distinct forms with greater chi-square (χ2) and p < .0001.

In the overall, cluster 3 grouped mostly environmental concerns and technical insights on vineyard management or winery operations. Comments on water and energy usage can be easily found, along with several other production inputs or outputs that require proper management. Cluster 2 and cluster 5 despite sharing similar attributes and variables’ profile (male interviewees with +55 years old with top-level roles and from wine regions of the North of Portugal), distinct tiers of vocabulary were considered sufficient strong to branch out ramification R2 into two classes. In cluster 2, we can find vocabulary associated to concerns regarding the issue of rural population decline and biased development opportunities for different regions, the migration of key age groups and consequent lack of workforce or infrastructures. Cluster 5 gathers opinions concerning the wine community and regional wellbeing. Several discourses comment on the role of community development practitioners and planners, and the need for better sustainable and equitable economic development strategies for wine grape growers and rural communities in general.

Finally, in ramification R3 we see analogous lexicon related to sustainability knowledge and conceptualization. On the overall R3 clustered discourses related to good governance and sustainability management in organizations, with commentaries on ethics, values and integrity with the public or interested parties.

Also, the relation between discourse and knowledge structure may have been exposed. Even though both matters are very complex phenomena, it is defended in linguistic discourse analysis that both have an explicit relationship. Several authors have made interesting proposals in literature on the role of knowledge in discourse, saying that implicit knowledge may be shared by the members of a language community (van Dijk, Citation2003). If considering the lexical content and vocabulary used between cluster 1, cluster 4 and cluster 6, there are clear differences associated to interviewees’ core teachings regarding their body of knowledge. Three tiers of dialogue were therefore identified in each cluster. While opinions associated to institutional sustainability awareness were mostly grouped in cluster 4, commentaries more inclined towards organizational sustainability were in cluster 1. Discourses leaning further to corporate sustainability were gathered cluster 6. Even though organizational and corporate awareness can resemble, cluster 1 collects lexicon mostly commercial and business-like where opinions on the industry and how the business operates are shared, as well on its competitors and customers. Cluster 6 on the other hand, essentially gathers impressions on value-creation strategies and sustainable business models. Nevertheless, all shared the interest in the search for more integrated systems or business models. R3 may also illustrate the longing for a potential framework where value-adding activities are connected to create and report value over the short, medium and long-term.

Summarizing, the three macro ramifications and all six generated clusters can be described as: (R1) environmental domain: environmental impacts and risks (cluster 3); (R2) social-cultural domain: sustainable regional development strategies contemplating socio-economic aspects such as, the territory and socio-cultural attributes (cluster 2) and strategies to improve growers and business profit allied to the local economy development (cluster 5); (R3) corporate governance domain: with a comprehensive viewpoint-split on how the corporate world of wine can approach sustainability. Cluster 4 showed higher institutional concern, while cluster 1 and 6 tilted towards business performance and corporate responsibility concept.

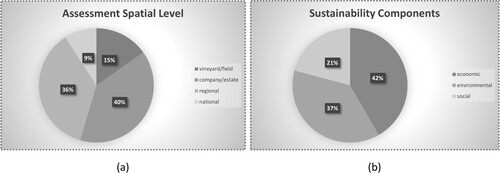

Results from the ranking questions were then analysed in order to emerge with a deeper and richer understanding of the participants’ impressions on sustainability assessment. One of the questions was based on rating the space dimension (scale and levels). Participants showed preference to first evaluate sustainability at the estate or company level and then regional, following field/vineyard level and national level accordingly (see (a)). This result is in concordance with the literature stating sustainability assessments at farm-level as the most used method, as fewer data starts being available from regional to higher scales (Olde et al., Citation2016).

Figure 4. Ranking questions results: (a) Graph illustrating the preference score for space dimensions of assessment; (b) Graph illustrating the preference score when weighting between the three fundamental components of sustainability.

When asked about the components of sustainability and their relative importance (weight), despite a general agreement on the importance of all TBL components, almost 70% of the participants considered convenient to give different weights when evaluating sustainability performance. After scoring their relative importance, 42% of the participants attribute higher value to the economic component, following the environmental with 37% and then the social with 21% (see (b)). Once again, this result is in harmony with former statements in literature defending a predominant focus on environmental and economic factors when dealing with sustainability issues (Merli et al., Citation2018).

On the other hand, 55% of the participants did not considered other components (such as governance) as a fundamental pillar of sustainability. This disregard of other sustainability components such as social, institutional, political and ethical factors has been as well reported in literature (Olde et al., Citation2016). However, when the distinction between political governance and governance at the enterprise level (corporate) was advocated during the interview session, there was a clear and general approval amongst the participants on the importance of the company’s leaders and top managers in terms of driving the entity towards sustainability thinking and engagement. Once more, this verdict has also been mentioned in previous studies with respect to the critical role of such managers and driving leaders amongst wine entities (Santiago-Brown et al., Citation2014a; Silverman et al., Citation2005).

Finally, in order to sketch a definition for sustainable wine production, the interpretation of higher-scored comments led to compose the following idea: in order to sustainably produce wine one must create boundless value, this is, also create value outside the wine company boundaries, while equilibrium is maintained based on long-term prosperity. In other words, if an organization is able to create value as an open-system while sustaining homeostasis, which includes not just assuring balance between survival and resilience but also growth and efficiency, then such business may be considered sustainable. This definition has its foundation on gathered meanings from the participants, and it is also aligned with both the TBL and the open-systems theory.

5. Discussion and interpretation of emerging theoretical categories

In advancing towards a deeper interpretation and discussion of the emerging clusters, it may be stated that sustainability awareness of the Portuguese wine sector can be sliced into three main domains of concern: environmental, social-cultural and governance. Despite this taxonomy may not be seen as astonishing as there is an unquestioned growing trend to consider the so-called ESG factors (Adams, Citation2015; Godelnik, Citation2021), their impressions and concerns go beyond the traditional TBL approach. In fact, as shown in , discourses tend to split into two strategic paths commanded by the horizontal and vertical axis in the Cartesian plane.

While the vertical axis separates measuring-impacts vs value-creation discourses, the horizontal axis distinguishes exposure vs orientation strategies. Hence, between clusters on the right quadrants and left quadrants we can find major differences regarding the awareness of wine industry’ impacts (often negative) vs the concern on considering better ways to create value (either for the community or the organization itself). Although, it should be endorsed the relevance to acknowledge both in an integrated way. As defended by Adams (Citation2015), it is not only important to measure historical impacts on the environment, society and economies in order to better manage, but the value created to wine businesses and its stakeholders should also be considered.

Regarding commentaries clustered on the top quadrants vs bottom ones, the biggest contrast is related to the decision-making and type of response on accountability issues. There is a clear distinction between strategies based on the communication of sustainable principles (exposure) and based on the implementation of sustainable practices (orientation). In other words, top quadrants gathered discourses and insights on how to highlight sustainability involvement of the firm, connect mainstream information to the exterior and communicate performance management. Thus, comments on different means and ways for marketing the sector’s products and services by underlining firms’ orientation towards sustainability. The bottom quadrants, however, gathered considerations on mainstream decision-making and how to not discharge accountability, as well ways to boost engagement towards a more sustainable approach. Here too it must be stated how sustainability reporting is important for accountability and has its role in targeting a wider stakeholder audience. However, as endorsed again by Adams (Citation2015), one should not neglect the fundamental need to simultaneously focus on both creating value while fostering a culture of accountability.

In order to better understand the three dimensions of discourse, highly scored TSs were also interpreted in context (step 3). The following subsections provide a further description of the macro ramifications and generated clusters considering discussed implications.

5.1. Environmental domain

An eminent debate and concern on environmental sustainability and wine industry’s negative impacts are clearly shown for results generating a distinctive and isolated ramification with one single cluster (cluster 3).

Similarly to the results in previous studies (Corbo et al., Citation2014; Ferrara & Feo, Citation2018; Fragoso & Figueira, Citation2021; Neto et al., Citation2013), several key environmental factors were mentioned as priorities to consider by the sector. Whether regarding viticulture cultural practices, cellar or winemaking processes, packaging, and even distribution or transportation approach. Grape growing practices, pest control strategies and water use for irrigation were by far the most important issues pointed out, even though pesticides including fungicides and herbicides seem to be the major burden. Proper alternatives are indeed being claimed in order to reduce its use and enable producers to face new environmental policies and pressures to discard synthetic agrochemicals. The importance of water for irrigation was also highly acknowledged regarding this being a scarce natural resource while also necessary to assure yield consistency and avoid extreme water stress.

Associated to the cellar and winemaking processes, there is a clear perception of the high energy usage, linked to winery activities largely due to temperature control, air conditioning, lighting, pumping, etc. Moreover, it was often defended how winery wastewater must be managed more appropriately regarding strategies for its capture, treatment or reuse.

Packaging and distribution issues were mostly referred when deliberating on carbon footprint and greenhouse gases emissions. Glass bottles are today highly debated not only because glass production is an energy-intensive activity but also due to their weight and its impact on transport emissions (Vázquez-Rowe et al., Citation2013). In fact, as an alternative to reduce emissions related to transport, several interviewees mentioned the importance of considering local bottling of branded wines at major export-markets. Despite modern bottling facilities have improved considerably to assure quality, and today large amounts of wine are being shipped in bulk from California, Chile and Australia to be bottled in Europe, bulk wine is still mostly used to make entry-level wines and particularly private label wines (CBI, Citation2016). This procedure can as well be more complex for PDO wines (protected designation of origin) due to European appellation laws that seek to safeguard the quality and image of protected wine regions. EU Regulation also covers rules for labelling, such as the need to include the indication of the bottler.

5.2. Social-cultural domain

This domain of concern generates two clusters, both with value-creation discourses and orientation strategic paths. Despite cluster 2 and cluster 5 illustrate distinct dialogues, it is understandable their connection as population growth along with productivity growth are often pointed as key components for local economic development (Avelar et al., Citation2019; Faria et al., Citation2020).

Participants often acknowledged local economic conditions playing a significant role in attracting and maintaining people in rural areas, as population lost affects local economy (Avelar et al., Citation2019). As perceived among commentaries gathered in cluster 2, population decline will not only bring consequences to local businesses but is correlated to the shrinking of workforce, which translates into a challenge to find seasonal workers to work in the vineyards. Several of the interviewees mentioned this affair as probably the biggest social-related issue now. Once again results were congruent with literature, where beyond the acceptance that businesses will struggle more, an aging population will also add more pressure on local governments (with a smaller tax base) to neglect the investing in essential attractive services such as infrastructure and public schools (Avelar et al., Citation2019).

In cluster 5, most of the issues pointed out by participants regarding regional socio-economic context were related to the level of the community vitality, living standards and if wine grape growing activity (as the main economic activity in these regions) was profitable and attractive enough to retain population in such areas. According to participants, one of the biggest reasons for population loss in rural wine regions was the fact that smallholder viticulture is not profitable on a general basis. A feature already reported by Faria et al. (Citation2020) when firm size, age and productivity were among others, identified as key factors influencing the economic performance of wine businesses within the Portuguese wine industry. Cluster 5 also collected several statements with value-adding strategies for local economy recovery such as adding value to the wine bottle by promoting quality or by increasing its potential value as an investment. Another remark was to rise the average unit value of wine grapes payed within regional borders in order to increase grape growers income and encourage future generations to continue with the family business and thus remain in the territory.

In the overall, we can find statements on the economic performance of winegrowing businesses, opportunities to improve winegrowing profitability and the importance to promote value-adding strategies among stakeholders. Farm size was also referred to have a critical influence on business’ performance, mostly in terms of return ratios and efficiency, an effect also exposed by other studies (Santos et al., Citation2020; Santos et al., Citation2021).

5.3. Governance domain

Governance domain is illustrated by ramification R3 that generates three different classes with analogous lexicon related to corporate sustainability. In general, vocabulary on business performance, corporate responsibility and how the industry should underline its orientation towards sustainability was gathered. Nevertheless, findings indicate potential correlation between sustainability awareness with level of involvement or technical knowledge, achievement motivation and role played in the industry. As previously shown in , ramification R3 is placed in quadrant Q1 with a clear inclination to enhance the degree of communication (exposure) of the sustainable orientation in order to create value for the organization and shareholders.

In cluster 4, we could identify discourses on the necessity to evaluate sustainability in order to better manage wine businesses and to move these by ethical awareness. In cluster 1, ways to benefit from communicating sustainable orientation and good practices already adopted by the organization were often mentioned. Cluster 6 on the other hand is a collection of statements regarding corporate responsibility and the necessity of being capable to choose between trade-offs when making decisions.

Despite several discourses on ethics, the challenge of being able to bridge the perspective-paradox between environmental and social benefits with economic profits and involved costs, continues to be ceaseless. In fact, several participants shared the principle to first assure that the activity is beforehand economically viable, coinciding with the idea defended by Santiago-Brown et al. (Citation2014b, p. 16) where ‘a sustainable farm or vineyard is the one that is able to economically provide for the farmer while maintaining its ability to consistently produce and improve quality over time’.

Considering that practising sustainable agribusinesses requires addressing not only economic goals primarily, but to seek for dynamic balance amongst all dimensions (Trigo et al., Citation2021), the norm of continuously assess and evaluate to adjust and optimize in any given situation should be always applied. Moreover, the process of knowing how to address tensions and paradoxes amongst different sustainability goals is critical. By recognizing the existence and value of interdependent and sometimes conflicting objectives, helps to better handle the situation of working in a complex-conflicting context (Anzivino et al., Citation2021).

Regarding the Portuguese wine sector, data revealed tensions associated to the paradox of performing vs organizing (Anzivino et al., Citation2021). The paradox of performing refers to the need to face tensions related to shareholders and other stakeholders’ goals or demands. This paradox is connected to the vertical axis regarding the demand of creating value to the company and favour financial outcomes by managing risks, against accountability for the impact their activities have across nature or society. On the other hand, the paradox of organizing is related to the horizontal axis and the decision to include sustainability practices in the business logics (exposure) or adopting such for improvement and orientation sake, going beyond market perspective (Anzivino et al., Citation2021).

Despite tensions related to both paradoxes could be overcome through a unified approach by adopting and integrating all strategic profiles, there is one missing piece in the puzzle that did not emerge within the analysis. The study’s findings reveal the omission of classes belonging to the top-right quadrant (Q2) of the Cartesian plane. This quadrant illustrates discourses based on impact-assessment and exposure strategies, which by some means did not create strong clusters when analysing content. Thus, revealed tensions may be resolved if wine businesses act based on strategies that go beyond ESG factors (illustrated by the three identified strategic-profiles), and start to incorporate to what extent businesses’ activities are having a positive or negative impact across all its surroundings. In other words, in order to handle complex and conflicting objectives, the wine industry must align internal with external values by intervening in all four different domains identified, namely value-creation, impact-assessment; exposure and orientation strategies.

Finally, this missing piece of adopting exposure strategies based on impact-assessment can be achieved through public policies and regulations (one of the sustainability dimensions neglected by participants) with a key role in the transition to sustainability (Boutroue et al., Citation2021; Gupta et al., Citation2022; Zakowski & Mace, Citation2021). The European Green Deal may be the starting point for such solution, and the new common agricultural policy the key to secure achieving its objectives and targets. The recent CAP reform, which is due to begin in 2023, is described as fairer, greener and more performance and results-based, with a stronger emphasis on local conditions and needs (European Commission, Citation2022).

6. Conclusion and recommendations

Due to the lack of quality data from the wine sector, covering a wider geographical scale and going beyond the environmental-spec, several face-to-face interview sessions with wine experts from Portugal were performed. Key insights shared between participants were empirically analysed and collectively interpreted based on a grounded theory approach to capture participants’ viewpoint on sustainability meaning; identify major issues of concern; and spot potential tensions and paradoxes.

Results showed that the perception of sustainability by the Portuguese wine sector can be sliced into three main domains of concern that resemble the so-called ESG factors. However, the factorial disposal of identified discourses’ clusters over a Cartesian plane exposed different strategic profiles for each domain based on how sustainability can be approached. From sustainability issues being addressed by the need to measure impacts vs create value, to being perceived through an external exposure vs inward orientation attitude. Each set of viewpoints is associated with a profile of concerns, which will then determine what strategy may be chosen when dealing with a specific sustainability issue.

Moreover, spotted tensions also showed the absence of discourses on exposure strategies based on measured impacts across their surroundings (Q2 of the Cartesian plane). Even though most of the participants mentioned the importance to evaluate environmental affairs, an orientation strategy to better manage environmental risks that might affect production costs and the company’s revenue was implied. The measuring of positive or negative impacts across nature, society and territory, from activities companies are invested in, was often overlooked.

New solutions may therefore rely on the adoption of approaches that go beyond ESG factors. It is suggested to start assessing and creating alignment on impact and dependency measurements across all sustainability dimensions, by integrating social, environmental and corporate governance with political orientations. New public policies and regulations such as the EGD may be a crucial starting point, but even the impact of these new policy measures must be measured for monitoring the progress towards sustainability goals.

From a practical point of view, this work may help wine managers and policy-makers as it navigates through real-time scenarios and reporting of concerns. By exposing perspective-patterns, we hope to support the development of future policies and sustainability guidelines. Theoretically, this paper fills a literature gap by gathering and analysing countrywide information often difficult-to-access. A new theory on the meaning of sustainable wine production was also put together, defending the need to create boundless value on the long-term while seeking to maintain equilibrium between growth vs efficiency, and survival vs resilience.

As final remarks, it is considered critical to encourage corporate actors to shift their mind-set and think broader of what is value-creation. Only then boundless value can be created and equitably managed for enduring prosperity. Corporate sustainability should be about that, an incessant search for more integrated systems and business models where the higher aim is the creation and preservation of value over the short, medium and long-term. Also, Portuguese wine companies should be encouraged to approach sustainability in a disruptive way by looking towards accountability, transparency and responsibility.

In this regard, this study recognizes the development of a framework capable to monitor, evaluate and guide businesses towards sustainability efforts in a widely comprehensible language, as a clear trend among the wine industry in Portugal. According to obtained results, such sustainability framework should be designed to assess at lower levels and gradually evolving towards national scale, while at the same time being used as a communication tool so producers can marketing their sustainable image. The development of regional or national sustainability programmes is probably the clearest evidence of this direction for the near future. Nevertheless, any forthcoming initiative for the Portuguese wine industry should always be accompanied by actual improvements not only at the company’s revenue level, but also in key environmental and social issues.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, C. A. (2015). The international integrated reporting council: A call to action. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 27(c), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2014.07.001

- Anzivino, A., Galli, M., & Sebastiani, R. (2021). Addressing tensions and paradoxes in sustainable wine industry: The case of the association ‘Le Donne del Vino’. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(8), 4157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084157

- Avelar, A. B., Silva-Oliveira, K. D. D., & Pereira, R. S. (2019). Education for advancing the implementation of the sustainable development goals: A systematic approach. International Journal of Management Education, 17(3), 100322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100322

- Baiano, A. (2021). An overview on sustainability in the wine production chain. Beverages, 7(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7010015

- Boutroue, B., Bourblanc, M., Mayaux, P. L., Ghiotti, S., & Hrabanski, M. (2021). The politics of defining maladaptation: Enduring contestations over three (mal)adaptive water projects in France, Spain and South Africa. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 0(0), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.2015085

- Bryman, A. (2012). In A. Bryman (Ed.), Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press Inc.

- Camargo, B., & Justo, A. M. (2013). IRAMUTEQ. Tutorial para uso do software de análise textual IRAMUTEQ. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina.

- CBI. (2016). CBI product factsheet: Bulk wine in Europe. Hague, Netherlands. https://www.cbi.eu/sites/default/files/market_information/researches/product-factsheet-europe-sustainable-wine-2016.pdf

- Corbo, C., Lamastra, L., & Capri, E. (2014). From environmental to sustainability programs: A review of sustainability initiatives in the Italian wine sector. Sustainability (Switzerland), 6(4), 2133–2159. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6042133

- Costa, J. M., Oliveira, M., Egipto, R. J., Cid, J. F., Fragoso, R. A., Lopes, C. M., & Duarte, E. N. (2020). Water and wastewater management for sustainable viticulture and oenology in South Portugal – A review. Ciencia e Tecnica Vitivinicola, 35(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1051/ctv/20203501001

- Dunne, C. (2011). The place of the literature review in grounded theory research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2010.494930

- Elkington, J. (1994). Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California Management Review, 36(2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165746

- European Commission. (2022). The new common agricultural policy: 2023-27. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/cap-overview/new-cap-2023-27_en

- Faria, S., Lourenço-Gomes, L. S. D. M., Gouveia, S. H. C. D., & Rebelo, J. F. (2020). Economic performance of the Portuguese wine industry: A microeconometric analysis. Journal of Wine Research, 31(4), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571264.2020.1855578

- Ferrara, C., & Feo, G. D. (2018). Life cycle assessment application to the wine sector: A critical review. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(2), 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020395

- Flint, D. J., Golicic, S. L., & Signori, P. (2011). Sustainability through resilience: The very essence of the wine industry. In 6th AWBR International Conference, (June), 1–12. http://academyofwinebusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/8-AWBR2011-Flint-Golicic-Signori.pdf

- Flores, S. S. (2018). What is sustainability in the wine world? A cross-country analysis of wine sustainability frameworks. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172(2018), 2301–2312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.181

- Fraga, H., Santos, J. A., Moutinho-Pereira, J., Carlos, C., Silvestre, J., Eiras-Dias, J., Mota, T., & Malheiro, A. C. (2015). Statistical modelling of grapevine phenology in Portuguese wine regions: Observed trends and climate change projections. Journal of Agricultural Science, 154(5), 795–811. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859615000933

- Fragoso, R., & Figueira, J. R. (2021). Sustainable supply chain network design: An application to the wine industry in southern Portugal. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 72(6), 1236–1251. https://doi.org/10.1080/01605682.2020.1718015

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1999). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206

- Godelnik, R. (2021). Rethinking corporate sustainability in the Era of climate crisis: A strategic design approach (Palgrave M). Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- González-Esquivel, C. E., Camacho-Moreno, E., Larrondo-Posadas, L., Sum-Rojas, C., de León-Cifuentes, W. E., Vital-Peralta, E., Astier, M., & López-Ridaura, S. (2020). Sustainability of agroecological interventions in small scale farming systems in the Western Highlands of Guatemala. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 18(4), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1770152

- Gupta, D., Davidson, B., Hill, M., McCutcheon, A., Pandher, M. S., MacDonald, D. H., Hamilton, A. J., & Mekala, G. D. (2022). Vegetable cultivation as a diversification option for fruit farmers in the Goulburn Valley, Australia. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 20(1), 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.1923286

- IVV. (2022). Estatística. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.ivv.gov.pt/np4/estatistica/

- Jones, G. V., & Alves, F.. (2012). Spatial analysis of climate in winegrape growing regions in Portugal. In Proceedings of the 9th International Terroir Congress, Burgundy, France, 25-29 June, 2012.

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1966). The social psychology of organizations. Wiley.

- Keichinger, O., & Thiollet-Scholtus, M. (2017). SOECO: Socio-economic indicators for viticulture and innovative cultural systems. In BIO Web of Conferences 40th World Congress of Vine and Wine, 9. https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20170904012

- Matos, C., & Pirra, A. (2020). Water to wine in wineries in Portugal Douro region: Comparative study between wineries with different sizes. Science of the Total Environment, 732(2020), 139332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139332

- Mcghee, G., Marland, G. R., & Atkinson, J. (2007). Grounded theory research: Literature reviewing and reflexivity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 60(3), 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04436.x

- Merli, R., Preziosi, M., & Acampora, A. (2018). Sustainability experiences in the wine sector: Toward the development of an international indicators system. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172(2018), 3791–3805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.129

- Moggi, S., Pagani, A., & Pierce, P. (2020). The rise of sustainability in Italian wineries: Key dimensions and practices. Electronic Journal of Management, 1(2020), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.15167/1824

- Montaigne, E., & Coelho, A. (2012). Structure of the producing side of the wine industry: Firm typologies, networks of firms and clusters. Wine Economics and Policy, 1(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wep.2012.12.002

- Neto, B., Dias, A. C., & Machado, M. (2013). Life cycle assessment of the supply chain of a Portuguese wine : From viticulture to distribution. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 18(3), 590–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-012-0518-4

- Ofstehage, A., & Nehring, R. (2021). No-till agriculture and the deception of sustainability in Brazil. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 19(3–4), 335–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.1910419

- OIV. (2004). Resolution CST 1/2004-development of sustainable vitiviniculture.

- OIV. (2021). State of the world vitivinicultural sector in 2020. Paris, France: International Organisation of Vine and Wine. http://www.oiv.int/public/medias/7298/oiv-state-of-the-vitivinicultural-sector-in-2019.pdf

- Olde, E. M. D., Oudshoorn, F. W., Sørensen, C. A. G., Bokkers, E. A. M., & Boer, I. J. M. D. (2016). Assessing sustainability at farm-level: Lessons learned from a comparison of tools in practice. Ecological Indicators, 66(2016), 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.01.047

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Pomarici, E., & Vecchio, R. (2019). Will sustainability shape the future wine market? Wine Economics and Policy, 8(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wep.2019.05.001

- Ramos, M., Valderez, L., & Amaral-Rosa, M. (2019). IRAMUTEQ software and discursive textual analysis: Interpretive possibilities. In A. P. Costa, L. P. Reis, & A. Moreira (Eds.), Computer supported qualitative research advances in intelligent systems and computing (pp. 58–72). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01406-3

- Santiago-Brown, I., Metcalfe, A., Jerram, C., & Collins, C. (2014a). Transnational comparison of sustainability assessment programs for viticulture and a case-study on programs’ engagement processes. Sustainability (Switzerland), 6(4), 2031–2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6042031

- Santiago-Brown, I., Metcalfe, A., Jerram, C., & Collins, C. (2014b). What does sustainability mean? Knowledge gleaned from applying mixed methods research to wine grape growing. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(20), 232–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814534919

- Santos, M., Rodríguez, X. A., & Marta-Costa, A. (2020). Efficiency analysis of viticulture systems in the Portuguese Douro region. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 32(4), 573–591. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-10-2019-0052

- Santos, M., Rodríguez, X. A., & Marta-Costa, A. (2021). Productive efficiency of wine grape producers in the North of Portugal. Wine Economics and Policy, 10(2), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.36253/wep-8977

- Silverman, M., Marshall, R. S., & Gordano, M. (2005). The greening of the California wine industry: Implications for regulators and industry associations. Journal of Wine Research, 16(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571260500331574

- Tait, P., Saunders, C., Dalziel, P., Rutherford, P., Driver, T., & Guenther, M. (2019). Estimating wine consumer preferences for sustainability attributes: A discrete choice experiment of Californian Sauvignon Blanc purchasers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 233(2019), 412–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.076

- Trigo, A., Marta-Costa, A., & Fragoso, R. (2021). Principles of sustainable agriculture: Defining standardized reference points. Sustainability, 13(8), 4086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084086

- Trigo, A., Marta-Costa, A., & Fragoso, R. (2022). Sustainability assessment: A tool to build resilience in the face of future crisis. In D. Vrontis, A. Thrassou, Y. Weber, S. M. R. Shams, E. Tsoukatos, & L. Efthymiou (Eds.), Business under crisis, volume III (1st ed., pp. 47–86). Palgrave Studies in Cross-disciplinary Business Research, In Association with EuroMed Academy of Business.

- Troiano, S., Marangon, F., Nassivera, F., Grassetti, L., Piasentier, E., & Favotto, S. (2020). Consumers’ perception of conventional and biodynamic wine as affected by information. Food Quality and Preference, 80(2020), 103820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103820

- van Dijk, T. A. (2003). The discourse-knowledge interface. In G. Weiss & R. Wodak (Eds.), Critical discourse analysis (pp. 85–109). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230514560_5

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(148), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

- Vázquez-Rowe, I., Rugani, B., & Benetto, E. (2013). Tapping carbon footprint variations in the European wine sector. Journal of Cleaner Production, 43(2013), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.036

- Von Bertalanffy, L. (1950). An outline of general system theory. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 1(2), 134–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/I.2.134

- WASP. (2021). Wines of Alentejo sustainability programme. Retrieved October 28, 2021, from http://sustentabilidade.vinhosdoalentejo.pt/en/wines-of-alentejo-sustainability-programme.

- Zakowski, E., & Mace, K. (2021). Cosmetic pesticide use: Quantifying use and its policy implications in California, USA. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 20(4), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.1939519