?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Quality seed is one of the most important farm inputs. The Ituri province, in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), faces enormous challenges in implementing a coherent formal seed sector, an essential gage for seed quality. This study aimed at diagnosing the Ituri seed value chain to propose improvements at all levels. Data collection was conducted using focus group discussions and direct interviews with key players at all levels, household surveys across the province, and a review of seed intervention programme reports, farm visit reports and other literature. Results showed that the seed system in the northeastern DRC is mainly informal due to several socioeconomic and technical factors. Less than a third of crops in the region had a formal seed delivery system. The cash flow in the seed sector was high owing to high seed demands from humanitarian organizations and farmer support structures, estimated at ∼1.5 million US$ in 2022 for the top three commercial seed commodities (common beans, maize and peanuts). However, the province seed production capacity through formal pathway is low (only ∼35 and 69% of the demands for common bean and maize, respectively, are covered by local productions), meaning that the seed demand is met either through importation or fraudulent conversion of farmer-saved seed. Due to lack of technical capacities, Ituri seed multipliers mainly produce open pollinated and synthetic varieties, while hybrids are imported from neighbouring countries. The lack of functional breeders in the provincial seed production chain, disproportionately low seed multipliers-to-distributors ratio, the weakness of the seed certification and regulation services, the border porosity, poor coordination among actors, and low awareness of farmers on seed qualities and advantages of using certified quality seed are the main structural and functional factors hindering the well-functioning of northeastern DRC seed system. This study provided an insight on the characteristics, stakeholders and challenges facing the seed sector in northeastern DRC and proposed an action plan for its improvement.

1. Introduction

The use of quality seed plays a major role in small-scale farmers’ food security and income stability, as it allows to achieve high yields and superior harvest quality (Ghebreagziabiher, Griffin, et al., Citation2022; Hambloch et al., Citation2021; McGuire & Sperling, Citation2016; Nabuuma et al., Citation2022; Njingulula et al., Citation2014; Vansant et al., Citation2022). Empirically, only good-quality seed allows to recoup investments from farm inputs such as pesticides, fertilizers, irrigation, etc. (CTA, Citation2007; Kuhlmann et al., Citation2023). The seed genetic background determines the plant’s characteristics: its food quality attributes, yield potential, resistance to disease and insect attacks, tolerance to various climatic conditions and even its shelf life. The farmer’s income and food security depend on these plant characteristics (McGuire & Sperling, Citation2016). However, farmers can only capture the benefit of the genetic gains from breeding programmes that develop such superior varieties when seed systems are well-functioning (Mausch et al., Citation2021; Stuart et al., Citation2021).

The term ‘seed system’ refers to the different channels that farmers use to obtain planting materials, encompassing activities related to crop diversity conservation, variety development, seed production and delivery (Ayenan et al., Citation2021; Haug et al., Citation2023; Nduwimana et al., Citation2022). Seed systems can be generally grouped as ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ sector systems, depending on whether seed producers or seed companies followed the seed certification procedures implemented by national and international seed regulatory bodies (Ayenan et al., Citation2021; Nduwimana et al., Citation2022; Sperling & McGuire, Citation2012). The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) seed industry is made of the two parallel systems: the informal sector and the formal sector (Mabaya et al., Citation2017). The informal sector, in which farmers produce, obtain, store and distribute seed resources from one production season to the next, is predominant in DRC (Nabuuma et al., Citation2022). This predominance of the informal seed system is attributed to factors such as limited awareness, lack of a wide variety of seeds, limited financial resources to purchase seeds and limited access to formal seed suppliers. On the other hand, the formal seed sector focuses on the selection and evaluation of improved varieties, and the production and marketing of certified seed (Nduwimana et al., Citation2022). It is regulated by legislation incorporating quality control, certification and institutional support (Ayenan et al., Citation2021; Nabuuma et al., Citation2022). However, with the emergence of humanitarian non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that subsidy seed access to small-scale farmers, a third seed system is now gaining pace. This is the so-called community based seed system or community seed banks (CSBs) in which NGOs and other farmer support structures acquire good-quality seed from the formal system and avail it to farmers in the informal system (CTA, Citation2007; Vansant et al., Citation2022).

The DRC seed sector is underdeveloped and suffers from the lack of a nationwide seed sector plan. This sector is characterized by low availability of quality seed among small-scale farmers, who mostly rely on farmer-saved seeds, seed exchanges or purchase of low-quality seeds from informal seed distributors. Consequently, yields among local farmers for staple crops are low and disease and pest incidences are high owing to uncontrolled seed flow among farmers and across regions (Mondo et al., Citation2019). In fact, key informal seed system challenges include low germination and vigour, disease contamination and build-up and inadequate quantity and diversity of seed (Louwaars & de Boef, Citation2012; Nabuuma et al., Citation2022). The situation is worse in the Ituri province, in the northeastern DRC, a region under precarious humanitarian and security situations due to persistent wars and ethnic violence (Nigo et al., Citation2021). Indeed, these long conflicts have destroyed all initiatives undertaken to develop the agricultural sector in general, and the province’s seed sub-sector in particular. This is the case, for example, of the outright destruction of the seed infrastructure installed by the Ituri Project Office (BPI) and more recently the ‘Centre d’Adaptation et de Production de Semences Améliorées’ (CAPSA) in Pimbo, rehabilitated by the ‘Stabilisation de l’Est de la RDC pour la Paix’ (STEP) project, both funded by the World Bank. The same applies to part of the infrastructure of the National Institute for Agricultural Research and Studies (INERA) Nioka, the public agency mandated for breeding and plant genetic resource conservation in the province.

Despite multiple supports received since 2001 from DRC international partners, with the aim of revitalizing the seed industry in Ituri, the latter has not recovered and faces numerous challenges. A diagnosis of the seed value chain in Ituri province is necessary to establish an effective seed action plan at provincial and territorial levels, as recommended in similar contexts by other scholars (Andrade-Piedra et al., Citation2020; Ghebreagziabiher et al., Citation2022a; Stuart et al., Citation2021). This implies a thorough understanding of the current status of the seed sector, mapping of actors involved in the sector and their relationships, and the identification of their challenges and opportunities (Nduwimana et al., Citation2022). This study was, therefore, conducted in response to this gap and was specifically aimed at (a) ensuring seed traceability in the Ituri province; (b) mapping direct and indirect players across the seed sector; (c) analysing factors driving the seed sector using a macro-level approach based on Political, Economic, Social, and Technological (PEST) analysis for the entire seed system; and (d) proposing an effective action plan for Ituri seed sector. Though most governmental and non-governmental interventions are focused on formal seed delivery pathways, this study used information from both formal and informal seed systems to draw its conclusions. Previous studies in eastern DRC showed that a functional seed system is not enough to boost improved varieties’ uptake by farmers if their varietal preferences are not considered (Mondo et al., Citation2019; Mugumaarhahama et al., Citation2021). This explains the rationale of gathering information on various aspects such as variety preferences, seed use and sources, regulation and stakeholders, etc. to ensure that not only conclusions will help fix the seed value chain but also will boost adoption of quality seed of introduced varieties.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Presentation of the study area

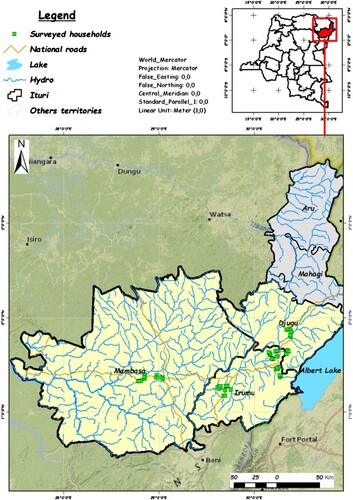

Ituri is one of the DRC provinces with a broken seed system, partly due to long political instability. This broken seed system undermined initiatives towards intensifying agriculture in the province despite governmental and non-governmental investments in the sector. Conscious of how a broken seed system had affected the agricultural sector and the complexity of challenges faced by stakeholders at all levels, this independent research was commissioned by governmental, non-governmental and private stakeholders to gain insights to whether there are opportunities to enhance this sector to deliver the much-needed seed for farmers and to propose a realistic action plan. Therefore, this study was conducted in the Ituri Province, northeastern DRC, from March 6th to May 3rd, 2023. Since 2015, Ituri has been one of the 26 DRC provinces, with Bunia as its capital city. It covers 65,658 km2 and is located on the western slopes of Lake Albert (). It borders Uganda to the east, South Sudan to the north, the Provinces of Nord-Kivu and Tshopo to the south and the Province of Haut-Uélé to the west. It comprises five administrative territories: Aru (6740 km²), Djugu (8184 km²), Irumu (8730 km²), Mahagi (5221 km²) and Mambasa (36,783 km²) (AZES, Citation2017; CAID, Citation2017).

Ituri Province enjoys two types of climate: tropical (Aru and Mahagi as well as part of Irumu, and Djugu) and transitional climate between equatorial and semi-arid climates (Mambasa, part of Irumu, and Djugu) (AZES, Citation2017; CAID, Citation2017; Ngabicwaka, Citation2022). It has a wide range of soil types, offering opportunities for several kinds of crops: Ferralsols and Ferrisols from undifferentiated bedrock (such as granites, schists and basalts), Kaolisols with dark horizons, tropical black and brown soils on alluvium (AZES, Citation2017; CAID, Citation2017). Ituri is a region of high plateaus (800–2000 m above sea level) dotted with a large tropical forest but also savannah landscapes. This province harbours a rich fauna with rare species such as the Okapi (in Mambasa territory). Its flora is also richly populated. Ituri Province shares its waters with both the Nile and Congo River basins. In general, Ituri is a well-drained region, offering a sufficient water supply to the population practicing agro-sylvo-pastoral activities despite climatic changes (AZES, Citation2017).

Ituri Province has a population of 5–9 million (the exact number is unknown) and a density of ∼64 inhabitants/km² (CAID, Citation2017; Nigo et al., Citation2021). It has a diversity of ethnic groups: Pygmies, Bantus, Semi-Bantus, Nilotics and Sudanese. This diversity is often at the root of inter-ethnic conflicts in the province (AZES, Citation2017; CAID, Citation2017; Nigo et al., Citation2021). Indeed, the province has experienced political and security instability for several decades. As a result of this instability, the province was placed under a state of siege in 2021, with civilian authorities replaced by military and police authorities (Oxford Analytica, Citation2021).

In this province, the population livelihoods include: (a) agriculture, which plays an important role in the province’s economy, with cassava, common beans, maize, bananas, sweetpotato and peanuts as the main food crops; cabbage, amaranth, onions and eggplants as major vegetables, while coffee, cocoa and tobacco dominate cash and perennial crops; (b) livestock, dominated by cattle, goats, sheep, pigs and backyard poultry; (c) fishing in the Lake Albert coastal zone at Mahagi, Tchomia and Kasenyi; and (d) trade and transport, which enjoy significant trade with Uganda (AZES, Citation2017; CAID, Citation2017; Ngabicwaka, Citation2022; Nigo et al., Citation2021).

Areas directly covered by data collection included Mambasa, Irumu and Djugu (), areas where Trôcaire’s partners (the Irish NGO that funded this study) are operational and where road access and safety are guaranteed. The research covered two chiefdoms per territory (with the exception of Mambasa, where only one chiefdom was covered for security and logistical reasons). These were the chiefdoms of Walendu Bindi and Bahema Sud in Irumu Territory; Bahema Nord and Bahema Badjerhe in Djugu Territory, while the chiefdom of Mambasa (more specifically the Nyangwe and Mputu areas) was covered in the Mambasa Territory. In addition to these three territories, the Bunia City was included in the study as the headquarters of NGOs, research institutions and government departments exerting a significant influence on the seed sector in these territories. Besides, the major seed companies (distributors and producers) are represented in Bunia.

2.2. Identification of crop species and varieties and assessment of farmers’ varietal preferences in Ituri

2.2.1. Identification of species and varieties grown in Ituri

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were organized with resource persons in each target territory (making a total of four focus group discussions for the entire study), bringing together 10 people representing the main seed value chain players (two leaders of farmers’ organizations or cooperatives (including one woman), one territorial or chiefdom agronomist or its extension agent, one clergyman, two seed multipliers (including one woman), one member of the civil society, one local administrative authority, two seed vendors/ distributors/ seed companies (including one woman)). The discussion, led by an interview guide and a checklist of species and varieties, aimed at characterizing the crops, their relative importance in terms of use and spatial distribution, the types of varieties used (local landraces, improved, hybrids, synthetics, etc.), the mode of seed access, the seed sources, etc. In each territory, diagonal observations were also conducted to identify the species and varieties as well as farming practices found in the study areas. A household survey involving 300 respondents (100 households per territory) enabled to identify the crop species used at household level and their relative importance. Since the exact number of households in each territory was unknown, a probabilistic saturation sampling technique was used to define the sample size in each selected zone (Hennink & Kaiser, Citation2022). In this sampling technique, the survey only ceases when interviews or observations of new participants no longer reveal new information. As the subject of seeds is of a general nature in rural DRC, no specific criteria were used to select households in rural areas, though surveyors were dispersed to ensure a representative sample. The questionnaire was administered to the head of the household. However, in his/her absence, an adult member of the household was interviewed. Prior informed consent of the respondents was taken and the study objectives were described to them as approved and directed by the Institutional Review Board (Ref: CNES 014/DPSK/322PP/2023). Besides, consent was obtained from all resource-persons, enterprises and households prior focus group discussions and data collection after ensuring the participants of the confidentiality in use of data collected.

Among seed suppliers or distributors (wholesalers or local sellers), the following aspects were discussed: origin of seeds sold, quality of seeds required by buyers, dynamics of seed prices over the year, seed packaging and storage facilities, ease of seed import and export, and knowledge of regulatory texts governing the seed sector. To sample in this stakeholders’ category, we used a list of seed distributors registered by the ‘Service National des Semences’ (SENASEM), the public seed regulating agency in DRC, from which 13 seed distributors were randomly selected. Reaching every selected seed distributor was achieved either through a snowball technique, with one respondent leading to the next (Etikan et al., Citation2016), or through a local guide provided by the SENASEM. Volumes of commodity flow under formal seed system for the year 2022 was sourced from the SENASEM annual report released in February 2023. Using average price at the local seed markets, we estimated the cash flow in the seed sector, by multiplying the total volumes of seed sold (as declared by registered seed distributors) for each crop by the average price of a kilogram for that specific crop.

The only public agricultural research centre in the province, namely INERA Nioka, was consulted (using in-depth interview) on the origin and availability of foundation seed, the conditions for maintaining the stock seed’s purity, and their relationship (in terms of institutional support) with the seed multipliers. Additional information on species, major uses, most predominant varieties, production zones, etc. was obtained after in-depth interview with the Provincial Inspectorate of Agriculture (IPAGRI)’s experts. The latter also provided access to annual territorial reports of Mambasa, Irumu and Djugu. The questionnaires used for surveys, key informant interviews and FGDs have been provided in the annex (see Supplementary File).

2.2.2. Assessment of farmers’ preference criteria for staple crop varieties in Ituri

A deep analysis of farmers’ preference criteria for released varieties is of great interest to seed system’s stakeholders to determine attributes driving variety adoption decisions among local farmers (Asrat et al., Citation2010; Mausch et al., Citation2021; Mondo et al., Citation2019; Ndeko et al., Citation2022). For this study, standard preference criteria (see standard descriptors for each crop) were used in the assessment of grown varieties of the staple crops in the zone. These included yield potential, taste, resistance to stock pests, seed price, earliness, drought tolerance, low input requirements, disease tolerance/resistance, seed longevity under storage, dry matter content, response to fertilizers, market demand, adaptation to local environment, culinary qualities, and seed availability and access. Such analysis helped elucidate and rank potential causes of low improved varieties’ adoption rate in Ituri.

To gain a better understanding on this matter, information on varietal preference criteria and seed system constraints was analysed using the Rank Based Quotient (RBQ) method. Standard variety attributes and constraints were predefined, and farmers rated each of them as high (1), medium (2) or low (3) according to their perceptions, designated by a ranking of first, second, or third, respectively. Thus, the RBQ method enabled to prioritize the criteria and to identify the most important constraints for the Ituri seed value chain. To achieve this, we used the following formula:

where i = concerned ranks, N = number of farmers, n = number of ranks and fi = frequency of farmers for the ith rank.

2.3. Mapping of seed industry’s direct and indirect actors and their roles in the Ituri Province seed sector

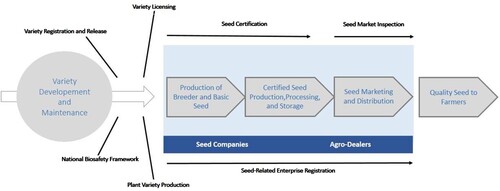

Stakeholders mapping considered the entire seed value chain, including diversity conservation, varietal selection and introduction, seed multiplication (including adaptation and yield performance trials, and released variety maintenance), seed conditioning (processing and packaging), storage, distribution and marketing (). Players intervening at different seed value chain levels in Ituri were identified and mapped according to whether they are public or private; seed multipliers or seed companies, legislative and regulatory services, farmers’ and seed sector’s support structures, academic, research or extension institutions; local, national, international organizations or United Nations’ agencies, etc. Once the stakeholders were identified, using official reports by the SENASEM and IPAGRI, direct in-depth interviews were organized with 10 of them to obtain more information on their roles in the seed system, their intervention strategies, target crops, intervention zones, challenges and their recommendations for a well-functioning seed sector. In addition to the interviews, their websites and online reports were consulted for further details (the website search included all relevant organizations not only those interviewed). Their list was obtained from SENASEM and IPAGRI annual reports.

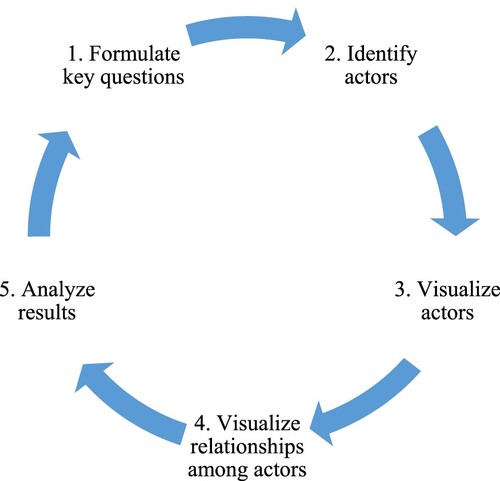

Stakeholders’ mapping followed the approach described in , which consisted of: (1) formulating key question(s) about the key players working at provincial and territorial levels; (2) identifying actors and hierarchizing them into 3 categories: direct, regulatory and support actors according to their degree of interest and influence on the seed sector; (3) visualizing actors by grouping them with respect to the phase of the seed value chain they intervene (research, regulation, varietal selection and maintenance, seed multiplication, packaging and seed marketing); (4) visualizing the relationships among players and identifying which of them are positive (to be encouraged) and which are negative (to be discouraged); and (5) analysing the result to ensure that the visualization corresponds to reality and that no player has been omitted.

2.4. Analysis of factors driving the seed sector using a macro-level approach based on political, economic, social and technological environments

Instead of a classical strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis that is more suitable for more micro-level analysis where it is applied for set of activities carried out by an individual group or enterprise which has a control on internal forces such as strengthening and weaknesses (Benzaghta et al., Citation2021; Puyt et al., Citation2023), this study considered a macro-level analysis based on Political, Economic, Social, and Technological (PEST) analysis for the entire seed system. PEST could provide a more holistic understanding, considering the multitude of stakeholders and multiple external forces involved in the Ituri seed sector (Cox, Citation2021). A PEST matrix was generated to effectively identify the political, economic, social and technological factors shaping the seed system in Ituri Province. Data collected from discussions with various seed value chain players served in the analysis. In addition to individual interviews and visits, a focus group was organized in Bunia with 15 representatives of key seed sector players in the province. These included INERA, SENASEM, Ituri local government, IPAGRI, a representative of seed multipliers and seed companies (RIMA), representatives of NGOs (FAO, WHH/AAA, Trôcaire, ICRC, ACF, HDC), two universities (Université Evangélique en Afrique (UEA) and University of Bunia (UNIBU)), and the private sector represented by the Ituri Chamber of Commerce and Industry (FEC). Discussions with these actors covered a wide range of topics: seed legislation and regulatory texts, coordination among stakeholders, stakeholders’ technical capacity and infrastructures, human and plant genetic resources, seed traceability and fraud, seed quality and certification procedures, seed industry challenges at all levels, etc. Similar focus group discussions were organized at the territorial levels with representatives of seed sector actors of Djugu, Irumu and Mambasa. Factors bearing influence on the seed system were identified, clustered (as political, economic, social or technological) and hierarchized to only focus on those factors which seemed to exert the strongest impact on stakeholders and were most likely to influence the seed system as directed by Cox (Citation2021).

2.5. Development of an action plan for the seed sector in Ituri Province

To define entry points for subsequent interventions aimed at improving the seed sector in Ituri Province, an action plan (taking into account local socio-economic realities and the cost-effectiveness ratio) was proposed based on key findings from the seed system diagnosis. All the essential seed system phases were considered: (a) management and conservation of plant genetic resources, (b) varietal selection and breeding, (c) maintenance and pre-basic and basic seeds’ production, (d) certified seed multiplication and marketing, (e) seed certification procedure and imports and exports regulation, (f) regulation of seed storage, processing and marketing. We mainly used the PEST analyses outputs to suggest the action plan for each of the seed value chain phase.

2.6. Data analyses

Data collected from the household survey were analysed using the software R 4.2.1 and RStudio (R Core Team, Citation2020). Frequencies (converted into percentages) were calculated for qualitative variables, while means followed by standard deviations were generated from quantitative data. As above mentioned, the RBQ method was used to identify the attributes driving varietal adoption decisions of staple crops. Microsoft Excel allowed cross tabulations and the drawing of figures presenting RBQ values. The information gathered from individual interviews and focus groups with key players in the seed industry was compiled in tables, and certain quantitative variables were encoded in Microsoft Excel to deduce trends by calculating means and standard deviations.

3. Results

3.1. Species and varieties of staple, vegetable and perennial crops in northeastern DRC

Based on household surveys, field and store observations, focus groups with resource-persons and public agencies working on agriculture and seed sector in the Ituri Province, at least 15 food crops are grown at varying degrees throughout the province (Table S1). These include cereals (maize, rice, sorghum and finger millet), pulses (common beans, peanuts, soybeans, cowpeas and sesame), roots and tubers (cassava, potato, taro, sweetpotato and yam) and bananas. Of these crops, common beans, cassava, maize and bananas dominate and play a major role in the food and income security of rural households in the region. Besides, 10 vegetable crops are grown for household consumption and market at equal importance, except for the squash, pineapple and chilli whose production volumes are negligible. Nine perennial crops (including fruit trees) are grown mainly for export owing to the absence of processing units locally. Of these perennial crops, cocoa and coffee (with both Arabica and Robusta coffees) are the most important. However, less than a third of these crops had a formal seed marketing circuit: this is mainly the case of staple food crops and vegetables, while no perennial crop had a formal seed delivery system in Ituri province.

Household surveys revealed the importance of crops within households: common beans (50.7%), cassava (48.6%) and maize (29.7%) were the most important crops. Further research is needed to assess the contribution of these major crops to the food system, and thus to guide actions to improve their value chains ().

Table 1. Staple crops practiced by households in surveyed areas of northeastern DRC.

The list of varieties in use for these major food crops and their relative importance are provided at Table S2. Overall, the three most grown staple crops (common bean, cassava and maize) had the highest varietal diversity regardless of the farmer location (Table S2). Indeed, there were 17 common bean varieties, 17 cassava varieties and 16 maize varieties across the region. There were also other varieties in use for these crops, but neither their names nor their origins are known by farmers. The efforts to ensure the traceability of varieties in use by households have been hampered by the following difficulties: (a) the change of variety names with locations; these are different from those registered in the national catalogue, (b) multiple introductions of the same varieties by different organizations and via different sources, (c) porous borders that do not facilitate control (Table S2).

3.2. Seed sources for major crops in Ituri Province

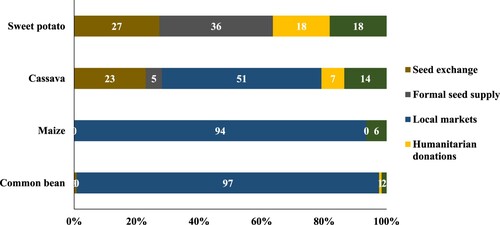

Informal seed system. The seed system in the northeastern DRC is mainly informal: most farmers access seed either from local markets (77.2%), previous harvests (6.8%), humanitarian donations to displaced and host families (4.5%), exchanges between producers (8.7%) and rarely through the formal circuit (via authorized seed multipliers and distributors, 2.9%) (). It is noteworthy that seed exchange among farmers is mainly limited to vegetatively propagated crops (cassava, sweetpotato and banana).

Table 2. Sources of seed used by smallholder farmers in northeastern DRC.

Focusing on the top 4 staple crops, namely common bean, maize, cassava and sweetpotato, we found that seed sources did not vary much with farmer location regardless of the crop (p > 0.05; Table S3). Farmers acquired common bean seeds mainly through purchase from local markets (96.8%) or previous harvest (1.6%). Less than 1% acquired seeds from humanitarian donations or seed exchanges. The trend was same for maize: 93.6% of seeds being acquired from local markets and only 6.5% recycled seeds from previous harvests (). Use of hybrid seeds is not a common practice in the Ituri province. Vegetatively propagated crops (VPC) such as cassava and sweetpotato had much diverging sources. In contrast to sweetpotato, cassava seed is a commercial commodity in Ituri, more than 50% of seed being purchased from local markets. Other cassava seed sources included seed exchanges among farmers (22.9%), previous harvest (13.5%), humanitarian donations (7.3%) and only 5.2% from certified seed suppliers. Sweetpotato seeds are not at all found at local markets, it was mostly acquired from certified seed suppliers (36.4%), seed exchanges among farmers (27.3%), humanitarian donations (18.2%) and previous harvests (18.2%).

Figure 4. Methods of obtaining seeds of the top 4 staple crops in Ituri. Sources indicated by farmers were those from which the seeds they were using at the time of the survey originated.

Other characteristics of the informal seed system in Ituri are provided in Table S4. In general, farmers rely on local landraces (80%) due mainly to limited access to seeds of improved varieties (46.2%), lack of information on available improved varieties (34.1%) and prohibiting high prices (15.7%). Another factor favouring the use of local landraces are the scarcity of seed distributors in the farmer’s vicinity (81.7%), and thus, most farmers spend at least 30 min to access the seed shop. Means of access to seed information are: other farmers (53%), farmer associations (17.7%), radios (14.5%), multiple sources (radio, other farmers and NGOs, 10.8%) and NGOs (4.0%). However, a third of farmers raised inadequacy between the seed information and their real performance when they grow it. Indeed, some of disappointing traits are poor adaptation to local environmental conditions (29.4%), poor seed quality (29.4%), disease and pest sensitivity (17.6%) and not meeting local varietal preferences (7.8%). The fact that 77% of the seed under informal system is acquired by purchase from local markets shows that seed marketing has a great potential in Ituri if the constraints raised above are addressed and proper pricing and packaging size are decided based on local farmers’ socioeconomic conditions.

Formal seed system. The seed regulating agency SENASEM reported that for the year 2022 (), a total of 407.5 ha of seed fields were grown for staple crops such as peanuts, common beans, soybeans, maize, rice, Irish potatoes and cassava. From that cultivated area, following seed productions were expected: 7200 kg of peanuts, 143,200 kg of common beans, 16,000 kg of soybeans, 173,250 kg of maize, 6000 kg of rice, 40,000 kg of Irish potatoes and 135,000 linear metres (LM) of disease-free cassava cuttings. However, when evaluating the quantity of seed sold through formal circuit, we found that there was an unbalance between the seed production and the seed demand. The gap is, therefore, filled by seed import or fraudulent conversion of seed from informal seed production. This is for example the case for common bean and maize for which only ∼35 and 69% of the demands, respectively, are covered by local productions. More details on which varieties are being used for these staple crops under formal seed sector are presented at Table S5.

Table 3. Area and seed production forecasts for major staple crops in 2022 in Ituri Province.

According to the SENASEM report (2022), 759,081.41 kg of seeds were marketed in the province. Of these, 755,879 kg were seeds of staple food crops and 3,202.41 kg of vegetable seeds (Table S6). No formal seed delivery exists for fruit and perennial crops in the Ituri province. These various seed lots were mostly purchased and distributed to vulnerable farmer groups by humanitarian and development organizations (ICRC, WHH, Samaritans Purse, ACF, CARITAS, SAVE THE CHILDREN and ADESSE) and United Nations agencies (such as FAO and UNDP). It is noteworthy that vegetable seeds are entirely imported from neighbouring countries such as Uganda and Kenya since no local seed producer has specialized in such crops. Of these, the most marketed are tomatoes (700 kg with the predominance of the variety CALJ (76% of the market share)), cabbage (724.63 with more than 91% of the market share from variety Copenhagen), epinard (700 kg), eggplant (439.2 kg) and amaranth (372.35 kg) (Table S5). In terms of monetary value, the three major grain crops (common beans, maize and peanuts) had more than 90% of the formal seed market share, accounting for ∼1.5 million US$ in 2022.

Despite efforts by seed producers to supply quality seed to farmers, they are hampered by limited access to basic (foundation) seed, since stakeholders intervening in varietal selection and maintenance are dysfunctional. As a result, basic seed is locally inaccessible and expensive, imported from other DRC provinces or neighbouring countries. Besides, seed multipliers recycle the same seed several seasons, with the risk of marketing degenerated seed that no longer meets quality seed standards. At Table S7, we list the basic seed producers for major crops in eastern DRC, where Ituri certified seed multipliers and other support structures can obtain basic seeds. These include INERA Kipopo (Haut Katanga Province) for maize, cowpea, soybean, peanut, cassava and rice; INERA Emiligombe (in the Tanganyika Province) for maize, rice and common beans; INERA Mulungu (South-Kivu) maintains varieties of several crops such as common beans, maize, sweetpotatoes, cassava, peanuts, rice, soybeans, etc.; INERA Yangambi (in the province of Tshopo) for maize, rice and common beans. In addition to food crops, INERA Yangambi maintains seeds for perennial crops such as coffee (Robusta), palm oil, cocoa and fruit trees. Varieties available in those research centres for various crops, together with contact details, are provided in Table S7.

3.3. Farmers’ preference criteria for staple crop varieties in northeastern DRC

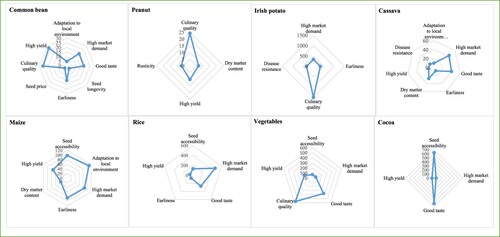

Common bean varieties are valued by smallholder farmers for a number of characteristics, including high yield potential, adaptation to local environments, local market demand, culinary quality, taste, seed longevity, earliness and seed price (). Of these, high yield potential (RBQ = 27.5), culinary quality (RBQ = 25.7%), high market demand (RBQ = 18.8) are the top three criteria while selecting common bean varieties. Peanuts are mainly selected based on four main criteria: culinary quality (RBQ = 24.3), high yield potential (RBQ = 10.1), dry matter content (RBQ = 6.4) and seed hardiness (, Table S8).

Figure 5. Farmers’ varietal preference criteria for staple crops grown in northeastern DRC. RBQ values for each attribute, its perceived importance by farmers and ranks are provided in supplementary Table S8. Perception on the seed price refers to smallholder farmers’ judgment on whether the seed is affordable or not.

For root and tuber crops, varietal preferences varied with crops. For instance, Irish potatoes are primarily selected based on the culinary quality (RBQ = 1500). Other traits such as disease resistance, early maturity and high market demand had equal importance (RBQ = 333.3). Farmers used a multitude of criteria to discriminate among cassava varieties of which high market demand (RBQ = 43.1), good taste (RBQ = 39.9) and high dry matter content (RBQ = 27.4) were top-ranked. Other important criteria were adaptation to local environments, disease resistance and earliness (, Table S8).

Maize varieties were selected based on six criteria, including, in order of importance, adaptation to local environments (RBQ = 108.9), seed accessibility (RBQ = 98.4), market demand (RBQ = 86.3), earliness (RBQ = 86.3), high yield potential (RBQ = 76.1) and dry matter content (RBQ = 32.7). Market demand (RBQ = 466.7) and taste (RBQ = 266.7) are the two main criteria used to appreciate rice varieties in Ituri Province, though some farmers considered also earliness, high yield potential and seed accessibility (, Table S8). Adoption of cocoa varieties is driven by seed availability (RBQ = 625), good taste (RBQ = 625), high yield potential (RBQ = 50) and market demand (RBQ = 50).

Generally, vegetables are appraised based on five main criteria: culinary quality (RBQ = 569.6), good taste (RBQ = 375), high yield potential (RBQ = 166.7), seed accessibility (RBQ = 69.6) and market demand (RBQ = 69.6). Among these crops, onion varietal preferences are led by high yield potential and market demand. Cabbage, on the other hand, is mostly selected based on taste and yield potential. As for eggplant and tomato, the preference was driven by the fruit culinary quality. The adoption of pepper’s varieties depended on the seed accessibility at the local market ().

3.4. Seed value chain actors’ mapping and their relationships

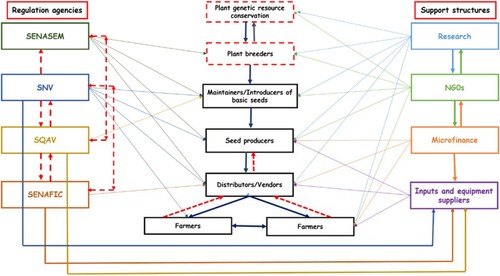

Stakeholders in the Ituri Province’s seed value chain were mapped based on different seed production phases ( and ). They were first clustered into three categories owing to their degrees of influence on the seed production chain: (1) direct actors (those directly involved in seed production and marketing), (2) regulatory services (state agencies ensuring the quality control of seed production and marketing processes across the province) and (3) support structures (actors outside the chain but providing assistance to direct and regulatory actors).

Figure 6. Relationships among stakeholders in the seed sector in northeastern DRC. Red dashed lines indicate abnormal relationships (or missing actors) affecting the seed quality in the region.

First, let us look at DRC seed value chain structure before appreciating the Ituri province situation (). In DRC, direct players include the managers and curators of plant genetic resources (gene bank); plant breeders and maintainers of pre-basic and basic seeds; certified seed multipliers or seed company; the seed distributors, suppliers, or merchants (these are actors mostly involved in the seed processing, packaging, or and marketing of seed without necessarily having produced it). There are also stakeholders involved in the seed certification (SENASEM) and import/export regulations (Service National des Fertilisants et Intrants Connexes (SENAFIC), Service de Quarantaine Animale et Végétale (SQAV), etc.). These are mainly public structures with mandates to ensure quality control across the seed production chain (i.e. seed production, seed processing, storage and distribution, seed import and export, etc.).

Support structures are made of local, national, or international organizations supporting farmers, seed producers and other stakeholders across the value chain. These support structures include NGOs, United Nations agencies, farmers’ associations or cooperatives, microfinance institutions, national extension services, agronomic research institutions, etc. In addition to these support structures, there are also players offering services to direct players in the seed value chain, such as transporters, farm inputs and equipment suppliers, media, etc. It is noteworthy that in some contexts, universities not only support research, but also help developing high-performance varieties and maintain their genetic identity. In such cases, the university plays a direct role and ceases to be a supporting actor.

There are some anomalies in the Ituri seed value chain (): (1) lack of coordination and trust among actors, (2) absence of well-functioning plant genetic resource management and breeding programmes, (3) a disproportionately low seed multiplier-to-distributor ratio (1:10), (4) fraudulent overlapping between formal and informal seed delivery systems, (5) poor import and export regulation, (6) opportunists driven by lucre with no awareness on the seed production requirements.

3.5. Characteristics of actors within the seed value chain in northeastern DRC

An inventory of actors intervening in the Ituri seed value chain is provided in Tables S9 and S10. Below, we discuss major characteristics of seed value chain actors in Ituri Province grouped based on the seed value chain phases:

Conservation of plant genetic resources/selection/maintenance of improved variety seeds. Although dysfunctional, the phase of the plant genetic resources’ conservation and management, varietal selection, and maintenance of breeder and basic seeds is ensured by ILA and INERA Nioka. Due to INERA Nioka’s weaknesses, basic seed is supplied to Ituri’s certified seed multipliers by various external organizations such as NASECO from Uganda, INERA Ngandajika, INERA Mulungu, INERA Yangambi, IITA Tshopo, etc.

Scientific research. Two local universities (Université Shalom de Bunia and University of Bunia) are active in the seed sector, supporting the introduction and multiplication of certified seed, not only through scientific research (focusing on stakeholders mapping and varietal adaptation/yield performance trials), but also by training other seed sector stakeholders. However, the research conducted on seeds is ad hoc (no specific research programme exists) and the results are not communicated to end-users.

Regulation and certification of the seed sector. Seed certification in DRC is an exclusive remit of SENASEM, and the Ituri office plays this role at the provincial level. This service is represented in rural areas by its territorial inspectors, who inspect seed multipliers’ fields and approve distributors’ stocks to ensure compliance with the national standards. Seed imports and exports at the provincial level are regulated by the SQAV and IPAGRI Ituri (via its PPV office) to ensure that plant materials (including seeds) entering and leaving the country comply with national and international requirements. As elsewhere in DRC, the agro-veterinary input shops (agro-dealers) that market most vegetable crops’ seeds are registered and regulated by the SENAFIC Ituri. All these structures are operational in Ituri Province, despite several technical and logistical challenges they face in fulfilling their mandates. Since the legislation regulating these state agencies is ambiguous, even at the national level, their interactions and coordination at the provincial level is poor and ineffective.

Support structures (mainly NGOs). Many local, national and international organizations are active in the seed sector in northeastern DRC (Table S9). Given the DRC state failure, which has disengaged from funding most of its agricultural services in the region, NGOs are involved in almost every phase of the seed value chain in Ituri. They support INERA Nioka in the introduction, maintenance and production of certified seeds, and come to the aid of SENASEM and seed multipliers (by facilitating the acquisition of working documents and basic seeds, covering inspection/certification costs, and training smallholder farmers, seed multipliers and SENASEM inspectors). In addition, NGOs are the main buyers of certified seeds in the province, which they distribute to displaced persons, their host families, and other vulnerable households since the province is under precarious humanitarian context due to recurrent armed violence. These organizations are also involved in structuring farmers’ organizations (including associations, cooperatives, AVECs, etc.), support state agricultural services (agronomists, local monitors and inspectors, etc.) and are even involved in setting up basic infrastructures and warehouses, rehabilitating agricultural feeder roads to facilitate the evacuation of agricultural produce, including crop seed. Therefore, these NGOs play a key role in the development of the region and assume a large part of the responsibilities that should fall to the Congolese government through its services.

Seed multipliers and distributors (agro-dealers). According to the SENASEM’s 2022 annual report, 39 seed multipliers and distributors were formally registered in 2022 (Table S10). As previously mentioned, the number of seed multipliers is low in the province (∼a tenth of seed vendors), and most of the players who identify themselves as such do not meet the required conditions (). The spatial distribution of these seed producers across the province is uneven, with more seed multipliers and agro-dealers located in Mahagi and Irumu territories and few of them are in Aru, Mambasa and Djugu. A visit to some seed multipliers in Irumu revealed a large number of opportunists who only acquire legal documents to trap funding from supporting structures and have neither the technical nor logistical quality to produce quality seed. It is noteworthy that seed multipliers mostly produce open-pollinated, synthetic, or vegetatively propagated varieties of staple crops that require less expertise, while seed distributors expand their activities to imported hybrids (mainly maize) and vegetable crops (e.g. eggplant, cabbage, amaranths, tomato, onion, etc.). Major suppliers of hybrid and vegetable seeds to local seed distributors are NASECO from Uganda and East Africa Seed Company from Kenya. Main characteristics of seed distributors in the Ituri Province are described in Tables S11 and S12. For both seed multipliers and distributors, crops focused on in terms of seed processing and storage practices are grain legumes (common bean, soybean and peanut), cereals (rice and maize) and almost all vegetable seeds. However, seed treatments with chemicals depend on the client’s preference regardless of the crop.

Table 4. Characteristics of seed multipliers in northeastern DRC.

Table 5. Seed processing and storage practices among seed multipliers in northeastern DRC.

Table 6. Characteristics of seed production fields and the seed multipliers’ awareness on seed qualities.

End-users (small-scale farmers). Ituri small-scale farmers have low education level (∼ two-thirds never attended or completed the primary school education). Most farmers had no interest in farmer associations (∼80%), and were located far from research centres (89%). Their source of livelihood was not diversified, more than 90% relying on farming for income and food, most of them possessed livestock (51%), and were unable to save (58%). Only 34% of the population could access financial credit while 74% had once benefited from agricultural credit or donations from humanitarian organizations in the forms of farm inputs (including seeds) or livestock genitors (Table S13).

3.6. Crop differentiation in seed delivery system of the top four crops

This section focuses on the top four crops and draws distinction between seed delivery systems for maize, common beans and vegetatively propagated crops (VPC) such as cassava and sweetpotato, emphasizing the differences in characteristics and seed system contexts. Based on the DRC seed regulations (as per the SENASEM procedure manual), all seed production should undergo the following steps: (1) registering as a seed distributor to the authorized service (SENASEM for the DRC); (2) registering as a seed producer; (3) registering the crop for inspection prior the field establishment; (4) providing a proof of origin of the seed to be multiplied (eligible variety for certification must have been released after National Performance Trials and distinction, uniformity, and stability (DUS) tests and approved for commercialization); (5) seed fields must be inspected to determine compliance with standards for varietal identity and purity, isolation, absence of noxious weeds and other species; (6) approved seed fields must be regularly monitored to maintain traceability; (7) harvested product (seed) must be inspected during conditioning and packaging; (8) representative samples of conditioned seed must be tested during conditioning for germination and purity to determine compliance with seed standards; (9) seed lots that meet standards are packaged and labelled, (10) certified seed lots must then be post-controlled every six months or each year depending on the species. Below are particularities for the top four crops in northeastern DRC.

Maize seed production and certification procedure in DRC. Permission to produce maize seed is granted to individuals or organizations within a suitable agro-ecological area, having permanently assigned agricultural technicians, a basic seed testing laboratory, facilities that can accommodate seed-related activities. The field management includes an adequate crop precedent (the field should not have received maize or another cereal the previous cropping season), an adequate plot isolation distance (at least 400 m for basic seed and 200 m for certified seed), rouging off-types during the vegetation and sorting of ears after harvest. During the vegetative and harvest inspections, maize seed field must comply with the following rules: proper plot labelling to facilitate identification, measure at least 1 ha for basic seed and 2 ha for certified seed, well maintained considering standard agronomic practices for the particular crop, be homogeneous to attest varietal purity, disease-free (a field with more than 0.1% infected plants must be rejected), free of noxious weeds such as Striga spp., Mimosa invisa, Rumex sp., etc. The maize being a cross-pollinated crop, the most critical inspection is performed at the flowering stage, the inspector comes at any time without prior warning to the seed multipliers. Certification of a field depends upon the number of inspections and inspector satisfactory reports. At harvest, seed lots are sampled: the minimum weight of a seed lot sample is 1000 g for laboratory tests and 1000 g for a priori and/or a posteriori tests; the lot size must not exceed 10 tons for basic seed and 40 tons for certified seed. Maize lots submitted for certification must meet the following standards (Basic seed; certified seed): (a) minimum varietal purity (98%; 98%), (b) minimum specific purity (99%; 99%), (c) minimum germination rate (90%; 80%) and (d) maximum moisture content (12%; 12%).

Common bean seed production and certification procedure in DRC. Common bean seed production is based on maintenance through conservative (genealogical) selection. Admission to inspection is granted separately or simultaneously for the following activities: producing basic seed and or producing certified seed. Individuals or seed companies are granted permission to produce common bean seed when their fields are in suitable agro-ecological zones, have permanent agronomists, basic seed testing laboratory and necessary facilities to conduct seed production activities. The seed categories include breeder materials, pre-basic seed (G1, G2 and G3 correspond to successive generations of multiplication of the starting material), basic seed (G4) and certified seed (R1). The seed production field must be checked for the following conditions: proper land preparation and crop establishment, the previous crop must not be a common bean or a related legume crop, proper seed density and sowing arrangement, adequate field isolation from another variety, rouging off-types during the vegetation, harvest conditions and materials, safety stocks, etc. During field and harvest inspections, common bean seed fields must comply with the following rules: proper plot labelling for proper identification, minimum plot size of at least 0.5 ha for basic seed and 1 ha for certified seed, proper isolation distance, well maintained based on recommended agronomic practices, high specific purity, high varietal purity, disease-free (disease incidence must be <0.1% and <0.5% for basic and certified seed fields, respectively), free from noxious weeds (maximum tolerances are 0.05% and 0.1% for basic and certified seed fields, respectively). Successful common bean seed certification depends on the number of inspections and positive reports from the SENASEM inspectors. The minimum weight of a seed lot sample is 1000 g; the lot size for pre-basic seed must not exceed 5 tons, while the basic seed lot must not exceed 10 tons, unless an exemption is granted by SENASEM. Mixing lots from different plots is prohibited while producing pre-basic seed. After laboratory testing, basic and certified seeds must meet the following standards: (a) minimum varietal purity (97%), (b) minimum specific purity (98%), (c) minimum germination rate (70%), (d) maximum of 4% grains other species in a sample of 1000 g, (e) maximum 0.05% weed seeds, (f) 12% maximum moisture content and (g) 2% maximum inert matter content (stones, earth, straw, etc.).

Cassava and sweetpotato seed production and certification procedure in DRC. Planting material for cassava and sweetpotato is produced by vegetative propagation of clones developed by research or a breeder after several rounds of selections. The following categories may be admitted separately or simultaneously: producers of basic seedlings and certified seedlings; collectors and shippers; and producers of mini-germinated cuttings using the rapid seed propagation technique. The permission to produce these crops’ seed is granted to the individuals or seed companies that are located in a favourable agro-ecological zone approved by SENASEM, possessing sufficient breeder/foundation material to ensure the renewal of seedlings, possessing suitable premises and means of protecting cuttings, having a basic laboratory equipped for phytosanitary tests and disease detection, and possessing sufficient number of qualified staff. The production system is based on pedigree selection from a healthy cutting and the resulting set is called B0. The production conditions are: the ‘B0’ starting material (must be free of viruses and other diseases); the ‘pre-basic’ selection material (B0 and B1) is grown in a research station or on a seed farm, B2 to B6 is grown by the producing company in its own geographical area; the plant seed categories include pre-basic plants (B0 to B2), basic plants (B3 to B6) and certified plants thereafter. Pre-cultivation practices (the best of which are improved fallow, cereals, legumes and other weeds); sanitary condition (for cassava, the focus is on diseases such as African mosaic virus, cassava brown streak disease and anthracnose, while for sweetpotatoes, the focus is on viral and bacterial leaf diseases); minimum plot size is 1 ha; proper isolation distance; signposting for easy identification; sanitary purification/rouging must start at the beginning of vegetation and continue until harvest, and crop condition (must allow for correct grading). For storage, cuttings are packaged in bundles of 50 or 100 cuttings, each one metre long, and can be stored for up to 6 weeks. For cassava, planting material to certify must meet the following standards: at most 15% of injured stems, 1% stems dry out during storage, at most 5% sprouted, misshapen or injured mini-cuttings, disease-free (5% anthracnose; 0.1% cassava bacterial blight). On the other hand, sweetpotato should not exhibit any sign of disease.

3.7. Political, Economic, Social, and Technological (PEST) factors driving the Ituri seed sector

Political factors influencing the seed system. The main factor shaping the seed sector in Ituri province is the low engagement of the government in funding research institutions. Besides, external partners are hesitant due to political instability characterizing this zone. Consequently, public research institutions and universities are unable to secure qualified personnel or conduct basic research on seeds and provide foundation seed to local seed multipliers. For instance at the time of data collection, INERA Nioka had no active plant breeder or seed scientist holding a doctoral degree. The centre was self-financing owing to the seed multiplication contracts with NGOs such as FAO, UNDP, ACF and the Republic’s Social Fund. This financial struggle explains the inability to attract qualified staff and acquire logistical facilities such as laboratory, means of mobility, computer equipment, etc. With the lack of basic seeds produced locally, everything is imported, with all the seed health risks that this entails. This is exacerbated by insecurity and porous borders, which render difficult to trace incoming seed. Moreover, the lack of basic seed discourages small-scale seed multipliers who lack necessary documentation and resources to import basic or foundation seed from neighbouring countries. Similarly, the University of Bunia (the largest public university in Ituri) has no staff with a master’s degree or doctorate in plant breeding, seed science and technology, or any other related field. Lack of devoted seed scientist means that these institutions have no permanent seed research programmes, making all actions ad hoc and unsustainable. In such a context, it would be unlikely to attract serious partners to support seed research in the region. Besides, seed-related content is weak in university curricula, implying that trained students are unlikely to contribute to the recovery of the provincial seed sector in the short- and medium-term (). This situation is luckily to worsen with degrading political and security situation; the province being placed under a state of siege since 2021, with civilian authorities replaced by military and police authorities. As it has been the case in other Congolese regions, the absence of a comprehensive national seed policy is a major political and or legal factor affecting the Ituri seed system. The text ambiguities encourages subjectivity in decision-making, leading to out-of-court settlements between SENASEM inspectors and offending parties. In addition to ambiguity in text, there is complacency in enforcing these legislative texts. This is partly due to staff precarious working conditions, who receive neither salaries (except for few mechanized agents), nor bonuses, nor operating expenses from the national and local governments, and lack the necessary logistics (laboratory for quality testing or mobility means to ensure inspections of fields that are sometimes far away). In fact, SENASEM Ituri rely on payments for services rendered to third parties, and has only one vehicle and 6 motorcycles for the entire province. Since SENASEM staff’s missions are directly paid by seed multipliers, distributors and NGOs requesting for services, these staff are unable to objectively enforce regulations. The lack of an up-to-date catalogue including vegetable and perennial crops makes it impossible to inspect and regulate the seed sector for these crops. The dysfunction of INERA and universities in the development of basic and pre-basic seeds, and the poor coordination among SENASEM, SENAFIC and SQAV in monitoring borders render it difficult to trace seed across the province ().

Table 7. Summary of main political, economic, social and technological factors and their influence on the seed system in northeastern DRC.

Economic factors influencing the seed system. The province is characterized by a poor business environment that discourages private investments. Since the legislative texts are ambiguous, external seed companies hesitate to invest in the region. Besides, there are multitudes of taxes, competition between commercial seed enterprises selling seed and humanitarian non-profit organizations distributing it free of charge. Local seed producers are not subsidized by the government, thus the production cost is high making them more vulnerable to competitions of foreign seed companies such as NASECO from Uganda and East African Seed Company from Kenya or fake suppliers. This competition is favoured by the region’s geographic position that opens it to eastern African countries where the seed industry is much more developed and the regulation much more conducive. Though not sustainable in the long run, the high seed demand by a multitude of international humanitarian and cooperation agencies (FAO, WHH, ICRC, Trôcaire, etc.) is a business opportunity to local seed actors who supply them seeds. The proximity to eastern African countries like Uganda and Kenya, where seed production sector is sufficiently advanced, helps Ituri seed multipliers to easily access basic seeds to compensate shortages in the province. This proximity also facilitates access to processing, conditioning and packaging inputs required in commercial seed production. Besides, this proximity allows technology transfer, by adopting technologies that have been proven effective in similar contexts in neighbouring countries ().

It is noteworthy that the lack of a conducive business environment for seed multipliers has led to disproportionately low seed multipliers-to-distributors ratio. By the way, buying grains from the market, conditioning it and converting it into seed is more profitable and less risky than producing standard quality seed. Producing certified seed requires appropriate personnel and logistics, inspection fees, the purchase of basic seed, manpower and security charges that informal distributors do not spend. Unfortunately, this makes seed multipliers less competitive when it comes to bidding for contracts, especially the price limit. This situation is exacerbated by the complacency of SENASEM, which certifies seed stock from fields it has not inspected. Besides, emergency humanitarian projects, which distribute seed free of charge, inhibit local seed entrepreneurship initiatives, as no small-scale farmer (household) will buy seed in an area where humanitarian organizations distribute it free of charge.

Social factors influencing the seed system. Northeastern DRC agriculture is mainly practiced by small-scale resource-poor farmers with low education level. Besides, they participate less in farmer associations and are located in remote areas with poor basic infrastructures (, Table S11). Only a third of the population could access financial credit. These factors are not luckily to favour agricultural innovations’ adoption, including quality seed of improved varieties. In addition to this, major NGOs working in the seed sector are less involving grassroots structures which could ensure their action sustainability. The variety’s dissemination strategies are mainly dissuasive, with little involvement of beneficiaries in decision-making. There is also poor coordination among actors, with several actors funding the same activities within the same community, but often with different intervention strategies.

Technological factors influencing the seed system. The Northeastern DRC seed system is faced with several technical challenges that explode the production cost and make it less competitive at the regional market. Farming is still manual with limited access to farm mechanization. With Ituri being a mineral-rich area, youth are more attracted by mining activities than farming, thus rendering scare and very expensive farm labor. There is a need for extensive farm mechanization to minimize production costs in the seed system. The other technical challenge is that all inputs used for seed processing and conditioning are imported, making their acquisition expensive. Besides, existing seed processing units are small and thus cannot benefit from the economies of scale. The low seed quality is also associated with the lack of qualified personnel in seed processing and seed testing laboratory, making the output hazardous and unreliable.

4. Discussion

4.1. Seed system in northeastern DRC is predominantly informal

Several crops are grown in northeastern DRC either for subsistence, market participation, or export. However, less than a third of these crops had a formal seed marketing circuit. For instance, no perennial crop had a formal seed delivery system in Ituri province. Therefore, most farmers (>97%) acquire seed through informal channels such local markets, farmer-saved seeds, humanitarian donations and farmers seed exchanges. This overreliance on informal seed sector is due to several factors such as the absence of formal seed delivery systems for most staple crops, limited access to seed suppliers in farmers’ vicinity, limited awareness on seed quality and existing varieties, lack of trust in formal seed distribution pathways, prohibiting high prices, etc. Similar factors were raised in other developing countries among factors favouring informal seed system (Ghebreagziabiher, Gorman, et al., Citation2022; Mabaya et al., Citation2017; McGuire & Sperling, Citation2016; Mondo et al., Citation2021; Rattunde et al., Citation2021; Rutsaert & Donovan, Citation2020; Sperling et al., Citation2021;Vansant et al., Citation2022). As in other sub-Saharan African countries (Kuhlmann et al., Citation2023), the situation is much worse for vegetable crops in eastern DRC, since farmers do not have much choice of quality seed of vegetable cultivars adapted to local growing conditions and consumer demand. No research institution nor seed company invests in local vegetable breeding research, while nearly all rely on seed imports (Kuhlmann et al., Citation2023).

The efforts to ensure traceability of varieties in use by households have been hampered by the following difficulties: (a) the change of variety names with locations; these being often different from those registered in the national catalogue, (b) multiple introductions of the same varieties by different organizations and via different sources and (c) porous borders that do not facilitate control. We found a differential varietal distribution across locations; meaning that there was little communication and exchange of planting materials among locations, which became geographically isolated. This geographical isolation can be partly attributed to precarious security in these locations over the last three decades, and to the deterioration of road infrastructures, which limit the movement of people and goods. The other probable factor explaining this differential distribution of varieties among territories is the province’s ethnic diversity, with each ethnic group having its own varietal preferences. The presence of varieties whose names and origins are unknown to local smallholder farmers could be a consequence of uncoordinated humanitarian actions distributing seed with no explanation provided to beneficiaries or local extension services. Besides, since territories are inhabited by farmers from different ethnic groups with different languages, we hypothesized that some of these varieties might be the same, but allocated different names across ethnic groups (Adewumi et al., Citation2021; Mondo et al., Citation2021). Thorough phenotypic and molecular characterizations would help avoid this ambiguity and enable define varietal catalogues of the existing crop and varietal diversity in Ituri Province, thus facilitating a sustainable use and conservation of the existing plant genetic resources (Mondo et al., Citation2021).

4.2. Stakeholders mapping revealed dysfunctional public actors and poor actors’ coordination

A well-functioning seed sector in Ituri would require harmonious coordination and trust among actors, which seems to lack among seed sector players in the province. This lack of coordination and trust often leads to overlap between actors, with the risk of wasting resources and effort by duplicating the same activities, or it could also lead to antagonism since some value chain players tend to substitute others. Besides, an analysis of the seed production chain in the Ituri province revealed a number of gaps in the seed value chain as compared to the national structure: there are no managers or conservators of plant genetic resources and no plant breeders, although these are crucial for a well-functioning seed value chain and an effective traceability of plant genetic material (including seed) flowing across the province (Ghebreagziabiher, Gorman, et al., Citation2022; Kobayashi & Nishikawa, Citation2022). INERA Nioka, which is supposed to maintain plant genetic resources and conduct breeding works, lacks human and material resources owing to the government’s financial disengagement. Consequently, this institution has become a seed introducer, maintainer and certified seed multiplier using imported basic seeds.

Another major abnormality in the Ituri seed sector is a disproportionately low seed multiplier-to-distributor ratio (1:10). Besides, some organizations identifying themselves as seed multipliers are in reality seed distributors or seed merchants. Hence, the imbalance between seed supply and seed market demand (mainly for staple crops such as maize or common bean) has favoured fraudulent behaviours (fake supplies). For instance, it is a very common practice for seed distributors to obtain off-the-shelf informal seed from local markets, which they package as formal seed to meet the market demand. Another anomalous relationship among players is the case where certain so-called seed multipliers acquire seed from seed distributors or vendors to meet urgent market demands. The lack of breeders in the provincial seed production chain, the imbalance between the number of seed multipliers and seed distributors, the weakness of the certification service (which certifies seed stocks coming from uninspected fields), the porosity of borders and frauds owing to poor coordination among state agencies, farmers’ low level of awareness of the seed qualities and advantages of growing certified seeds are structural and functional factors which result in the circulation of poor-quality seed and the difficulty of tracing varieties introduced into the province.

4.3. Challenges faced by the northeastern DRC seed value chain are both structural and functional

Seed value chain stakeholders face several challenges at all levels. All the state agencies recognized by the legislator are operational in Ituri Province, despite several technical and logistical challenges they face in fulfilling their mandates. Though SENASEM has most of the texts needed to improve seed regulation across the province, there is complacency in enforcing these legislative texts. This is partly due to staff precarious working conditions, who receive neither salaries (except for few mechanized agents), nor bonuses, nor operating expenses from the national and local governments, and lack the necessary logistics (laboratory for seed quality testing or mobility means to ensure field inspections). Since the legislation regulating these state agencies is ambiguous, even at the national level, their interactions and coordination at the provincial level is poor and ineffective. It is noteworthy that the seed regulation agency possesses no specific regulatory laws and procedures for vegetables as it was also noted by Kuhlmann et al. (Citation2023) in other African countries. These authors argued that regulatory approaches used in most African countries, namely mandatory value for cultivation and use (VCU) trials and state-controlled seed certification are not well suited for vegetables. NGOs play a key role in the region development and assumes a large part of the responsibilities that should fall to the Congolese government through its services. The major weakness of NGOs working in the seed sector is the low involvement of grassroots structures, especially local government agricultural services, which would ensure their actions’ sustainability. The variety’s dissemination strategies by NGOs are mainly dissuasive, with little involvement of beneficiaries in decision-making. Beneficiaries also criticized the distribution of mediocre quality seed by NGOs, often provided late with no respect to the cropping calendar. These NGOs should involve SENASEM in the seed supplier’s selection procedure to prevent fraud and the purchase of poor-quality seed.

Seed multipliers suffer mainly from the lack of a conducive business environment, making their production costs high. Some of the business environment factors affecting seed multipliers are lack of subsidies from governments, excessive bureaucracy and taxation, high farm and seed processing input costs since almost all inputs are imported, high labour cost, etc. In addition, weak regulatory services favours unfair competition opportunist fake suppliers who do not bind to any regulation. The later buy grains from the market, condition and convert them into seed and they profit more than registered seed multipliers who produce standard quality seed. In fact, producing certified seed requires appropriate personnel and logistics, inspection fees, the purchase of basic seed, manpower and security charges that informal distributors do not spend (Ayenan et al., Citation2021). Unfortunately, this makes seed multipliers less competitive when it comes to bidding for contracts, especially the price limit. This situation is exacerbated by the complacency of SENASEM, which certifies seed stock from fields it has not inspected. Besides, emergency humanitarian projects, which distribute seed free of charge, inhibit local seed entrepreneurship initiatives, as no small-scale farmer will buy seed in an area where humanitarian organizations distribute it free of charge (Njingulula et al., Citation2014; Rattunde et al., Citation2021).

With the lack of basic seeds produced locally, everything is imported, with all the seed health risks that this entails since border are porous due to insecurity (Saccaggi et al., Citation2021). Moreover, the lack of basic seed discourages small-scale seed multipliers who lack necessary documentation and financial resources to import basic seed from neighbouring countries. Varietal selection for basic seed production offers great opportunities, given the high demand for basic seeds in the province. This high seed demand attracts foreign seed companies such as NASECO from Uganda and East African Seed Company from Kenya, as well as national research centres such as INERA Mulungu, INERA Bambesa, INERA Yangambi, etc., which are taking advantage of INERA Nioka’s weaknesses. This institution’s financial struggle explains the inability to attract qualified staff and to acquire logistical facilities such as laboratory, means of mobility, computer equipment, etc. Lack of devoted seed scientists and breeders in the region means that these institutions have no permanent seed research programmes, making all actions ad hoc and unsustainable. In such a context, it would be unlikely to attract serious partners to support seed research in the region. Besides, seed-related content is weak in university curricula, implying that trained students are unlikely to contribute to the recovery of the provincial seed sector in the short- and medium-term.

On the other hand, the attractiveness of the seed marketing sub-sector partly explains the proliferation of opportunistic seed distributors who invade the seed sector with no awareness on minimum seed requirements and operating procedures. These opportunists are unknown by regulating agencies and have no legal documentation. Most players in this seed chain phase are not technically qualified (few have agronomists among the staff) and have little knowledge of the seed qualities and how to preserve them during seed processing, packaging and storage. These organizations also lack the necessary logistics for proper seed processing, packaging and storage. When looking at end-users (small-scale farmers), we found that their socioeconomic characteristics would not favour improved varieties adoption and formal seed use. They have low education level, rarely attend farmer associations, live far from research centres, they have low income mainly from agricultural activities, and rarely access financial and agricultural credits. These characteristics are, however, those not favouring agricultural technology adoption in eastern DRC (Mondo et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Mugumaarhahama et al., Citation2021). However, since 77% of households often buy seed from local market is an indicator that initiatives oriented towards formal seed marketing holds huge potential if factors creating gaps between seed distributors and farmers are closed. For instance, there is need to strengthen trust between formal stakeholders and farmers, design proper packaging size to fit resource-poor farmers’ purchasing power, increase distribution shops in farmer vicinity to minimize shop-to-household distance, etc. This could increase the cash flow within the formal seed system knowing that 3% of the total seed that had gone through formal channels had generated ∼1.5 million US$ in 2022.

5. Conclusions and prospective