ABSTRACT

Amidst the fast-changing consumer behavior and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, community-based enterprises (CBEs), particularly startups, face the challenge of identifying strategic business models. The situation necessitates a collaborative and tailored approach to address the impediments CBEs encounter. Focusing on rural CBEs in Thailand, our research employs a participatory approach to value chain development, offering insights on enhancing value addition through stakeholder collaboration. The study explores how a participatory approach applied in rural Thailand facilitates overcoming obstacles and capitalizing on opportunities for economic growth, sustainability, and community inclusivity. By examining the application of participatory value chain development, this research contributes to a better understanding of how participatory value chain development can be tailored to meet the unique needs of community-based enterprises, particularly in post-COVID-19 market adaptations.

1. Introduction

The recent Covid-19 pandemic has led to rapid and significant changes in consumer behavior, which requires firms, especially startups, to adopt strategic business models quickly (Békés & Kézdi, Citation2021; Jeenaboonrueang, Citation2019; Joiner & Okeleke, Citation2019). Traditional marketing practices are becoming less effective or preferred, especially in pandemic-impacted markets (Salamzadeh & Dana, Citation2021; Toiba et al., Citation2022). The recent global pandemic highlights the importance of a creative and more digital-focused approach towards marketing (Salamzadeh & Dana, Citation2021). For instance, the pandemic has accelerated the shift towards online channels, with businesses increasingly relying on social media marketing and search engine optimization to reach consumers (Aggarwal & Manaswi, Citation2022; Kitipadung & Jaiborisudhi, Citation2023). This shift towards digital marketing is evident in the rise of e-commerce platforms, social media marketing campaigns, and targeted online advertising. Similarly, farmers markets, agricultural cooperatives, and community-based enterprises started to embrace online platforms and social media to connect with consumers and sell their produce (Battistella et al., Citation2017; Kitipadung & Jaiborisudhi, Citation2023; Toiba et al., Citation2022).

The situation highlights the necessity to reinvent business models to align with new market realities after the pandemic extends beyond retail and merchandizing businesses, including those in the agricultural sector (Battistella et al., Citation2017; Joiner & Okeleke, Citation2019). In addition, this shift has particularly impacted community-based enterprises (CBE), which are integral to local economies, particularly in developing countries. As evidenced during the pandemic, food systems are vulnerable to such global phenomenon (MOTS, Citation2022; Toiba et al., Citation2022; Wentworth et al., Citation2024). Wentworth et al. (Citation2024) argued that food systems can be considered public goods, and the situation implies the need for community-based decisions regarding management and policymaking. This emphasis on community engagement aligns with the growing recognition of CBEs as a strategic approach to local economic development, especially in developing countries (Soaga & Makinde, Citation2014; Swash, Citation2007; Tantoh et al., Citation2021). CBEs operate at the grassroots level, empowering local communities to drive their development (L.-P. Dana et al., Citation2023; Soaga & Makinde, Citation2014). These CBEs, often deeply rooted in agricultural practices, face the dual challenge of adapting to changing consumer behaviors and the evolving digital marketplace (Cavite et al., Citation2021; Pradhan & Samanta, Citation2022; Soaga & Makinde, Citation2014).

CBEs are characterized by their participatory nature, involving community members in decision-making, ownership, and management(Peredo & Chrisman, Citation2006; Swash, Citation2007). This participatory approach fosters a sense of ownership within the community and leverages local knowledge and resources to address specific challenges and opportunities (Peredo & Chrisman, Citation2006). By involving community members in the planning and implementing development initiatives, initiatives are more tailored to the local needs and priorities, leading to more effective and sustainable outcomes.

In the Asian region, CBEs have demonstrated their potential to reduce poverty and increase self-reliance among rural farmers (Cavite et al., Citation2021; Chand et al., Citation2015; Laiprakobsup, Citation2018). Their diverse roles range from assisting government agencies in delivering public services to acting as catalysts for social and economic development, empowerment, collective production, marketing, and entrepreneurship (Contini et al., Citation2012; Neef et al., Citation2013; Welsch & Kuhns, Citation2002). On the other hand, the establishment of community enterprises in Thailand has seen significant growth, with a gradual increase from 2.8% in the 1970s to 11.6% by 2007, followed by a substantial surge in 2008 (53%) after the enactment of the Community Enterprise Promotion Act in 2005 (British Council, Citation2020; Cavite et al., Citation2021).

Although CBEs in rural Thailand receive agricultural support and training in farm production, engaging with formal markets remains one of the biggest challenges farmers face (C. A. Llones et al., Citation2022). A rapid assessment of several CBEs across rural Thailand revealed that distrust and a lack of understanding of business transactions with formal markets contribute to difficulties among CBEs. The recent Covid-19 pandemic further exacerbates the challenge. In response to the changes brought by post-COVID-19, CBE increasingly adopted online channels for sales, promotion, and advertising. However, this shift posed new challenges, such as maintaining a continuous online presence and dealing with logistics issues, particularly in remote areas. The paths for market access among CBEs vary, wherein some can independently establish their networks and access markets, while others rely on external support from governmental, private, and international agencies (L.-P. Dana et al., Citation2021; Laiprakobsup, Citation2018).

Despite efforts towards inclusivity and developing higher collective actions among CBEs, there are still documented cases of local communities being excluded (Swash, Citation2007). In efforts to improve inclusivity among rural farmers, a participatory approach is often integrated into establishing CBEs. Participatory approaches are widely applied across various areas such as in resource mapping (e.g. Brown et al., Citation2017; Burdon et al., Citation2022; Saija & Pappalardo, Citation2022), natural resources conservation (e.g. Kapoor, Citation2001; Neef et al., Citation2013; Nyam et al., Citation2020), and rural development (Kumnerdpet & Sinclair, Citation2011; Soaga & Makinde, Citation2014). On the other hand, the participatory approach towards value chain development serves as a catalyst for innovation, fostering collaboration and communication among various actors in the value chain and contributing to the development of new products and services. Due to the potential of applying a participatory approach toward value chain development among community-based enterprises, this study examines the development of rural CBEs through a participatory approach in Thailand. Insights generated from this research provide a comprehensive examination of how rural CBEs can enhance the value chain – from field to market – while navigating the challenges at the community level through a participatory approach.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 delves into the background of CBEs in rural Thailand, providing context for their unique challenges and opportunities. Section 3 outlines the research methodology, detailing the case study areas and the research design employed in this investigation. Subsequently, Section 4 presents the results and discussion, highlighting the key challenges in CBE-led value chains and illustrating the potential of participatory approaches for their development. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study by summarizing key findings and offering recommendations for enhancing the effectiveness and sustainability of CBEs in rural Thailand.

2. Community-based enterprises (CBE) in rural Thailand

Since the 8th National Economic and Social Development (NESDP 1997-2001) and the establishment of the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy (SEP) in the 1970s, developing local economies and rural regions has been a focus of the country’s national policies (Sitabutr et al., Citation2017). For example, the adoption of ‘One Tambon One Product’ (OTOP) in Thailand, which is inspired by Japan’s ‘One Village One Product’ (OVOP), showcases local products and services (Sitabutr et al., Citation2017). In Thailand, ‘Tambon’ is equivalent to a village, the smallest administrative district in the country. Hence, the OTOP concept is one of the country’s economic policies highlighting the development of local entrepreneurial activities, wherein the majority were implemented through CBEs to promote the local economy, especially in rural areas (British Council, Citation2020; Sitabutr et al., Citation2017).

CBEs in Thailand are diverse in their legal structures and can operate as cooperatives, associations, social enterprises, or even informal groups (British Council, Citation2020; Sitabutr et al., Citation2017). While primarily based in rural areas, their membership often includes farmers, producers, processors, traders, and consumers who are collectively invested in the enterprise’s operations (Cavite et al., Citation2021; Sitabutr et al., Citation2017). Typical CBEs in Thailand focus on producing agricultural commodities such as paddy rice, corn, and vegetables (British Council, Citation2020; Welsch & Kuhns, Citation2002). In addition, CBEs also extend their operations to include the manufacturing of agricultural inputs or value-added products. While Thailand’s enactment of the Community-based Enterprise Promotion Act in 2005 intensified the government support for CBEs, offering assistance in production, finance, networking, and marketing (Kitipadung & Jaiborisudhi, Citation2023; Sitabutr et al., Citation2017). This legislation recognized the critical role that CBEs play in value chain development. By facilitating collaboration among actors at different stages of the value chain, CBEs have the potential to enhance efficiency, reduce transaction costs, and improve access to markets, ultimately contributing to the livelihoods of their members (Sitabutr et al., Citation2017; Swash, Citation2007).

While the CBE Promotion Act in Thailand has significantly boosted the foundation and growth of CBEs by focusing on organizational management, production control, and network building, a crucial aspect remains a challenge regarding achieving effective market penetration and value chain integration. This difficulty highlights a gap in the traditional, top-down approach to value chain development, which often overlooks the unique characteristics of community-based enterprises (Kitipadung & Jaiborisudhi, Citation2023; Swash, Citation2007; Tan, Citation2021). Specifically, CBEs, rooted in community-based operations and collective marketing efforts, often lack the resources, expertise, and market power of larger, more established businesses. They also face challenges in coordinating their members’ diverse interests and needs, who may have varying levels of experience, knowledge, and access to resources. In this context, the participatory value chain development concept emerges as a promising approach, contrasting with traditional top-down models (Graef et al., Citation2014; Wentworth et al., Citation2024). While traditional value chains often operate with limited input from stakeholders outside of core decision-makers, participatory value chains actively engage all members in decision-making and implementation processes (Graef et al., Citation2014; Liu et al., Citation2023; Tan, Citation2021).

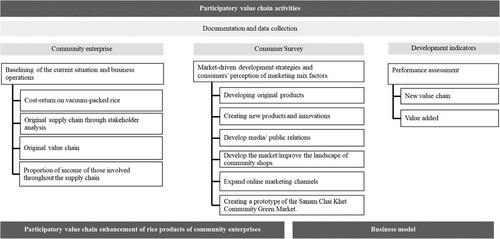

This study provides insights into the development of CBEs using a participatory approach toward value chain development. As illustrated in , this participatory process involves various approaches. The process involves a thorough documentation and data collection phase involving community enterprise baselining and consumer surveys. This information is used in developing market-driven strategies and identifies key development indicators for performance assessment. The process depicted in also highlights the importance of developing media and public relations strategies to raise awareness and build support for CBE initiatives. This approach improves operational and sales performance and adapts the value chain model to align with CBEs unique objectives, such as collective marketing and the empowerment of marginalized groups. The effectiveness of the participatory approach in development has been demonstrated in diverse contexts, including Albania, Bangladesh, Uganda, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines (Devaux et al., Citation2020). However, the distinct nature of CBEs, which necessitates collective action and community empowerment, requires a tailored approach.

3. Methodology

3.1. CBE case study areas and sample

The study uses an exploratory case study approach widely applied among business-model studies that considers the uniqueness of the focus subjects (Battistella et al., Citation2017; Contini et al., Citation2012; Tan, Citation2021). The research project began with two primary community-based enterprises and was expanded into five case study areas. The community enterprises area in (1) Ban Nong Saeng, (2) Ban Bueng Takhe, (3) Ban Na Ngam, (4) Ban Hin Rae, and (5) Sanam Chai Khet.

The selected CBEs are located in different regions of rural Thailand to capture the differences in the socio-economic and agroecological contexts where CBEs operate. The selected CBEs vary in maturity, ranging from relatively new enterprises to those with established operations. This variation provides an opportunity to examine how participatory approaches evolve and adapt over time as CBEs gain experience and expertise. The CBEs were also chosen based on their commitment to community engagement and participatory practices. Another consideration includes the CBEs that are accessible for research purposes and expressed a willingness to participate in the study. Lastly, the case study areas were verified through the provincial agricultural offices.

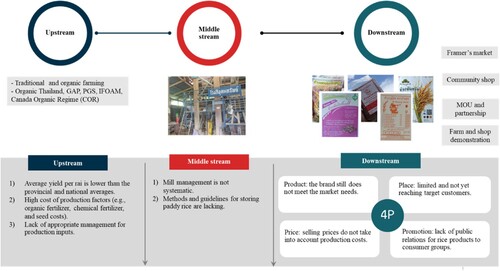

The participants in the study include local farmers, leaders of CBEs, representatives from government agencies involved in agricultural development, and traders. Focus group discussions were organized with local agricultural extension officers and community leaders. The discussions were facilitated using semi-structured interview guides, focusing on the challenges and opportunities faced by CBEs in the rice value chain. The FGDs and field visits revealed several challenges faced by community enterprises. These challenges span the entire value chain, as demonstrated in . For example, the rice output in the region is comparatively low, averaging 100 kg per rai (16 kg per hectare). The survey also discovered that CBEs lack efficient rice quality control. Also, the current marketing practices do not correspond with the identified preferences of the target audience. Nevertheless, these difficulties present chances to enhance the product’s packaging and branding, increasing its value to buyers. These community enterprises’ viability may have been at risk if the CBEs’ current marketing strategy and operations are maintained without resolving these issues.

3.2. Research design

The research design and analysis of the study are composed of two interconnected parts grounded in the principles of participatory research. This approach emphasizes the active involvement of stakeholders throughout the research process (Contini et al., Citation2012). Afterward, the business model canvas (BMC) was utilized to characterize the operation, financial, and marketing-related aspects of running a community-based enterprise. Under a participatory approach in the value chain development, ensuring the subjects’ involvement at every stage is critical (Contini et al., Citation2012). Following Defoer et al. (Citation1998), the participatory research process is divided into four integral phases: (i) diagnosis/analysis, (ii) planning, (iii) implementation, and (iv) evaluation.

During the diagnosis and analysis, the research team identifies issues and challenges with the focus CBEs. Building upon insights from the diagnosis/analysis stage, the research team and CBE members collectively craft actionable strategies. These strategies are tailored to address the unique challenges and needs identified. Afterward, continuous communication between the research team and CBEs is essential. The final phase involves assessing the impact of the interventions. This requires gathering data, reflecting on the outcomes, and understanding the implications for CBEs. Feedbacking also offers invaluable insights, enabling the research team and CBEs to appreciate the progress and identify areas for future improvement.

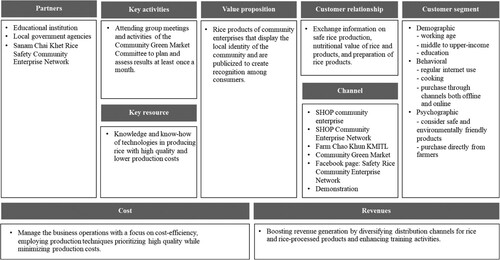

On the other hand, the processes from understanding current operations to conceptualizing a new business model are complex under community enterprise development. The study adopted the Business Model Canvas (BMC) developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2013). The use of BMC in the study is not a prescriptive exercise where the research team imposes a model but a collaborative process where CBE members actively map out their key activities. In addition, the participatory use of the BMC helps to identify strengths, weaknesses, and potential areas for improvement within each CBE’s business model.

The BMC’s visual and structured framework facilitates a collaborative process, enabling diverse stakeholders – including CBE members, farmers, and other value chain actors – to contribute their insights and perspectives. This aligns with the participatory approach of the research, ensuring that the resulting business models are co-created and reflect the collective knowledge and aspirations of the community. Furthermore, the BMC’s nine building blocks – including key partners, key activities, value proposition, customer relationships, customer segments, key resources, channels, cost structure, and revenue streams – provide a comprehensive lens for analyzing and optimizing CBEs’ value chains. By mapping out these interconnected elements, the BMC helps identify areas for improvement, uncover potential collaborations, and design innovative solutions that enhance value creation. Specifically, in rural Thai CBEs, the BMC can be instrumental in addressing market access, product differentiation, and financial challenges. For example, the BMC can guide CBEs in identifying key partners who can provide access to new markets or technologies, refining their value proposition to meet consumer needs better, and optimizing their cost structure to ensure profitability.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Key challenges in CBE-lead value chains

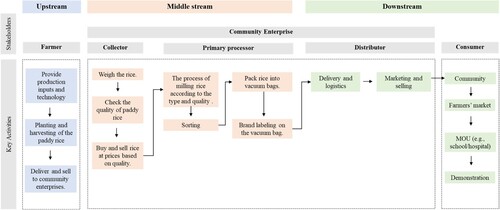

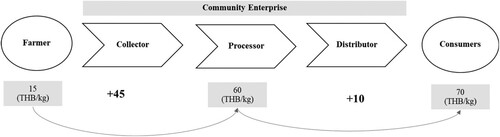

Through a qualitative approach, a series of focus group discussions that include farmers, CBE leaders, government officials, traders, and partner stakeholders, illustrates the overview of the rice value chain in rural Thailand’s CBEs. The CBE across the case studies areas in Ban Nong Saeng, Ban Bueng Takhe, Ban Na Ngam, Ban Hin Rae, and Sanam Chai Khet serves primarily as the collectors that ensure the quality and quantity of the processed paddy rice from members. For CBEs acting as the primary processors, their activities include milling rice paddy following a consistent quality, sorting, packing into vacuum bags for extended shelf life, and branding for market recognition. Several challenges arise within the value chain illustrated in , wherein farmers in the upstream often lack adequate post-harvest management practices, leading to inconsistent paddy rice quality. Maintaining consistent paddy rice quality is crucial to minimizing potential losses for CBEs (Pradhan & Samanta, Citation2022; Welsch & Kuhns, Citation2002). The situation indicates the necessity of focusing on developing the post-harvest skills of CBE members. In addition, the country’s agriculture industry has additional challenges due to the perceived insufficient budget allocated to research and development (R&D) and the persistent economic instability (e.g. the recent COVID-19 epidemic) (Srisathan et al., Citation2023).

As illustrated in , the establishment of CBE takes a larger part of the supply/value chain in the middle stream. While upstream of the supply chain are the rice farmers engaged in optimizing production inputs and farm technologies for delivering and selling their produce to CBEs. Members follow standards and quality requirements set by CBEs, which influence the production calendar of farmer members. Like the case studies of Liu et al. (Citation2023) for the value chain communities in Wuhan, China, the collective actions among villages influenced the traditional and fragmented production structure. Fragmented productions are typical among smallholder farmers, who comprise most Thai farmers. Smallholder farmers often rely on middlemen, traders, and commission agents due to the faster disposal of the harvests – albeit at a disadvantaged price offered (Koshy et al., Citation2021). Through a participatory CBE approach, organized farming provides technical and centralized market knowledge among fragmented farmers in Thailand’s rural areas (Amnuaylojaroen et al., Citation2021; Faysse et al., Citation2022). For local Thail agriculture officers, establishing farmer groups (i.e. CBEs) allows for a more straightforward implementation of agricultural support and assists farmers in marketing their products.

Moreover, CBEs act as the primary processors of paddy rice and are responsible for receiving and further processing rice paddy, including vacuum-packing and branding. This activity adds value to the product, strengthening and improving its market appeal (L. P. Dana, Citation2010). However, product design may not always meet the market demands, such as in the target supermarkets and specialized markets (Aggarwal & Manaswi, Citation2022; Tan, Citation2021; Verhofstadt & Maertens, Citation2013). Supermarkets and enterprises in Thailand hold a dominant position in the value chain and set the product standards, especially for organic certified or those adopting the Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) (Suwanmaneepong et al., Citation2023; Veisi et al., Citation2017). These requirements include product traceability, organic, and GAP certification logo displayed on the packaging. CBEs grapple with meeting stringent market demands and quality standards set by supermarkets and enterprises, particularly for organic and GAP certifications (Amekawa, Citation2013; Suwanmaneepong et al., Citation2023). Organic and GAP certification, particularly for smallholder farmers, are courses through farmer groups such as rural community enterprises.

Moving further downstream, community enterprises continue their role from processing to distribution. They are entrusted with ensuring that processed rice reaches varied consumers. Their activities in this phase involve handling delivery and logistics for transportation and engaging in marketing and selling strategies. However, they are weakened by a lack of solid planning for collection and market distribution and a deficiency in gathering consumer data for product improvement, which is crucial for aligning the product with consumer expectations and market trends. At the end of the supply chain are the consumers, who are the end beneficiaries and access the processed rice through various channels. This could be directly from community enterprise outlets, farmers’ markets, or even establishments like schools or hospitals through Memorandums of Understanding (MOU). Occasionally, the CBEs of the case study areas organized field demonstrations, which served as a platform to introduce a new rice variety or educate people on a particular type’s health benefits.

Despite these challenges, the participatory approach offers CBEs opportunities to enhance their value chain role. By actively involving farmers in decision-making and providing training on post-harvest techniques, CBEs can improve rice quality and consistency. Collaborating with supermarkets and enterprises to meet certification requirements can unlock access to premium markets. Developing robust marketing and distribution plans and systematic consumer feedback mechanisms can help CBEs align their products with market demands better.

4.2. Participatory approach in developing CBE value chains

4.2.1. Collective marketing in the CBE-lead value chains

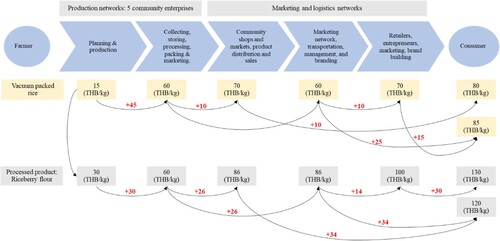

illustrates the value added at each chain before the project intervention in developing the CBE value chain through the participatory approach. The diagram hints at the lack of product diversification of the CBEs, which limits the potential of community enterprise value-adding activities. For CBEs taking the role of collector, processor, and distributor of farmers’ produce, the situation implies the immediate need to develop CBE innovations and marketing strategies. Hausmann et al. (Citation2007) emphasize that product development involves primarily market research and marketing efforts to establish demand for new product innovation. In addition, support for farmers, such as government policies, R&D, and facilitating the development of farmers’ social networks, significantly influence innovation and development of farmer groups (C. Llones et al., Citation2021; Saboori et al., Citation2023; Xie et al., Citation2021). To develop the product innovation of the CBE-led value chain across case studies, the project tapped the social capital of farmers through the participatory approach. The participatory approach has enabled organized production and marketing, improving rice farming and centralized market information.

Figure 4. Previous CBE’s traditional value chain showing the value added (THB/kg) at different chains.

On the other hand, shows the CBEs’ product innovations and the development of new products. In terms of enhancing the CBE’s products for market readiness, the process involves several key initiatives – packaging design and development, brand building, traceability, and public relations. For instance, the assortment of packaged goods showcases the upgraded aesthetic and functional packaging design, which is critical for product differentiation and consumer appeal in retail environments (Catur Rini Sulistyaningsih & Wisnujati, Citation2020; Ubilava & Foster, Citation2009; Zhou et al., Citation2022). Also, the product features strongly emphasize brand identity, which helps build consumer recognition and trust – developing a cohesive brand image across products aids in establishing a narrative that resonates with the target market.

Figure 5. Development and enhancement of the community enterprise products showcasing updated packaging, marketing materials, and branding strategies.

Moreover, incorporating traceability into marketing materials allows for a connection with consumers by highlighting the origins and values of the products. While incorporating a traceability system reinforces this by allowing consumers to track the product’s journey from farm to table. Ubilava and Foster (Citation2009) demonstrated that consumers’ willingness to pay is higher when a traceability feature is available in a product. Furthermore, the study found that willingness to pay is 48 percent higher for traceability information than for quality certification labels (Ubilava & Foster, Citation2009; Zhou et al., Citation2022). Consumer preferences are shifting, especially regarding food safety and ecologically friendly food production methods, which means that new products must be developed to meet changing market needs.

On the other hand, CBE explores several products for its production diversification strategy, including rice noodles, cereals, and flour. The community underwent prototyping Thai noodle products, which involves developing a viable prototype that has been tested and validated by consumers. In addition, training in marketing enables the CBE farmers to assess if the product is conceptually ready for market introduction, although it may require further refinement based on market feedback. In addition, like Thai noodles, rice cereal products are being tested in laboratory settings and with consumers to ensure that they meet quality standards and consumer expectations before proceeding to market scaling. Rice flour products have achieved full commercial status, indicating they have passed through the developmental stages, including rigorous testing and quality assurance, to ensure they are market-ready. As a result, demonstrates the improved value chain built for vacuum-packed rice and rice berry flour through the participatory approach used in developing CBE products and innovations. It illustrates two different paths for rice processing, emphasizing the impact of product diversification on the value chain. The rice berry flour undergoes a more extensive transformation, justifying the higher price increments at various stages. For instance, after initial processing, the price rises by 30 THB (0.82 USD), followed by an increase of 26 THB (71 USD) after further processing and packaging. This suggests that value addition for rice berry flour is significant during processing. As the flour goes through the same marketing and logistics networks, the incremental price changes are analogous to the vacuum-packed rice. However, the final consumer price reflects the additional processes and perceived product value, culminating in a higher end price of 50 THB (1.36 USD) than vacuum-packed rice. The participatory approach in developing a CBE value chain emphasizes integrating various stakeholders, from farmers to retailers, in the value-addition process. The differentiated price points also underscore the potential for increased revenue generation through product diversification and enhanced marketing strategies.

4.2.2. Changes in sales and cost savings

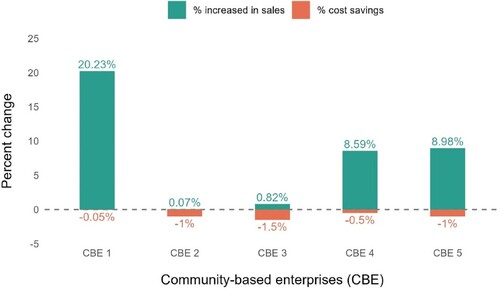

Across all enterprises, the main cost item was the purchase amount of rice from members, while other cost items varied across the enterprises, as summarized in . The cost of packaging materials (e.g. vacuum bags, stickers) and the vacuum compressor also contribute significantly to the total cost. At the same time, labor costs vary substantially among enterprises, which might reflect different labor use levels and machinery applications for processing. Fixed and other expenses are relatively smaller than the total cost since the amount accounted is equivalent to the depreciation value of the CBEs’ fixed inputs. However, these depreciation costs can influence the total cost, especially if they vary widely between enterprises. To improve the financial condition of the CBEs, the project target is to improve both the increase in sales and develop cost savings methods. The profitability of these enterprises is largely determined by how they manage their production costs and the pricing strategy they adopt (Srisathan et al., Citation2023; Suwanmaneepong et al., Citation2020; Welsch & Kuhns, Citation2002). The disparity in profit margins highlights the importance of efficient cost control, potentially indicating different competitive strategies, market positioning, and operational efficiencies among enterprises (Constantinides, Citation2006; Xie et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. Cost analysis and profit margins per kilo across community enterprises in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand.

CBE’s aggregated purchasing strategy has given community enterprises enhanced bargaining power, allowing them to secure more competitive pricing. This collective bargaining approach demonstrates the economic principle of economies of scale, where increased purchase volumes can lead to lower unit costs (Goodwin & Mishra, Citation2004; Wu, Citation2019). The cost savings and increased sales across CBE case studies in contribute to the enterprises’ financial sustainability and competitive positioning. For example, lower packaging costs can translate into increased profit margins or the opportunity to offer products at more competitive prices, contributing to an enterprise’s market share growth and long-term viability (Lamey et al., Citation2018). In addition, Wang et al. (Citation2018) demonstrate how strategic packaging affects the market demand for a product and the potential cost savings from efficient product packaging. It is also essential to consider the potential ripple effects of such savings, including the ability to reinvest in other aspects of the business, such as product development or marketing initiatives. For the CBEs, the strategic move to sell vacuum-packed rice with certified organic standards has proven economically beneficial for the community enterprises involved in the project. As shown in , the CBEs experienced positive sales growth during the project’s post-participation. For example, Ban Nong Saeng (CBE 1) exhibited the most significant growth at 20.23%, indicating a robust market demand for organic rice in that community and successfully aligning with consumer trends. The actual sales volume increased from 7,740 to 35,252 units, showing the substantial impact of the project. Comparatively, the other community enterprises have also seen improvements. For instance, Ban Na Ngam (CBE 3) demonstrated a 0.82% growth, which, despite being modest, still represents a positive trajectory in sales volume, climbing from 17,770 to 20,990 units. Ban Hin Rae (CBE 4) and Sanam Chai Khet (CBE5) saw increases of 8.59% and 8.98%, respectively, which are noteworthy increments indicating tangible benefits from their participation in the project.

Figure 7. Percent change of the production and cost savings across CBE participating in the project.

These enhancements in sales volume suggest that the enterprises’ decision to package milled rice in vacuum bags with organic certification has met with favorable reception. This can be attributed to the gradual and increasing preference for food safety and sustainable production, such as organically certified products worldwide (Appiah, Citation2019; Kasem & Thapa, Citation2012). It is essential to recognize that this strategy capitalizes on current consumer preferences and promotes sustainable agricultural practices. This also shifted Thailand toward safer and organic agricultural production methods through the country’s national program for organic farming (Baird, Citation2024; Moore & Donaldson, Citation2023).

In addition, the data suggests that the project’s influence on sales is not uniform across all enterprises. This invites an analysis of market dynamics, consumer behavior, and operational efficiency in each community. Additionally, while the percentage increase provides an immediate measure of growth, the long-term sustainability of these enterprises will depend on consistent quality, ongoing consumer engagement, and market expansion strategies. Further examination into the specific activities that contributed to this growth, such as marketing efforts, organic certification processes, or improvements in distribution channels, could provide deeper insights into the drivers of success. This would enable other enterprises to learn from these strategies and potentially replicate this growth in their operations.

4.3. Strategic guidelines for CBE-lead value chains

The BMC in presents nine integral components that interlink to form the blueprint of a CBE’s value creation across the case studies. In terms of partnership, the community enterprise collaborates with educational institutions and local government agencies, leveraging these partnerships to enhance its credibility and operational knowledge. At the same time, the value proposition centers on offering rice products that reflect the local identity and are recognized for their organic standards. This commitment to local branding and organic quality distinguishes the products in the market, aligning with consumer trends towards health and sustainability (Faysse et al., Citation2022; Suwanmaneepong et al., Citation2020; Teng & Wang, Citation2015).

Moreover, the BMC identifies diverse customer segments and distribution channels, combining traditional community enterprise shops with digital platforms such as Facebook, thus bridging the gap between offline and online commerce. Farm and product demonstrations are also vital as experiential marketing tools that engage customers effectively. While the enterprise’s resources are deeply rooted in the knowledge and technologies that allow it to produce high-quality rice at lower costs. This strategic resource allocation enables the business to stay competitive and innovative. A focused approach to managing business operations with cost-efficiency enables the enterprise to maintain affordability without compromising quality – a balance critical for long-term sustainability. Lastly, the revenue model boosts earnings by diversifying distribution channels and enhancing training activities. These revenue streams reflect a strategic approach to growing the enterprise’s financial health while expanding its market presence.

In addition, presents a comparative analysis of the key factors in the rice value chain among CBE case studies. It highlights the different skills and management practices contributing to their performance in this niche market. Farmer groups, CBE members, stakeholders, and partner institutions conducted consultations and group discussions to assess what constitutes ‘fair’, ‘good’, and ‘very good’ performance for each factor across the CBE case study areas. For instance, in production planning, the criteria primarily include documented production planning, the level of detail, and the extent to which the plan is implemented and monitored.

Table 2. Comparison of success factors in the vacuum-packed rice business across five community enterprises.

On the other hand, factors such as branding and packaging, marketing planning, and the diversity of rice-processed products relate to the value proposition, implying the need for CBEs to develop unique offerings that appeal to their target markets. As noted in , successful enterprises involve member farmers in branding decisions, which not only fosters a sense of ownership but also ensures that the branding resonates with the core values of the community. The affiliate network’s strength is another critical factor, providing robust support for production and marketing. As the market evolves, there is a noted push for an online presence, necessitated by changing consumer behaviors and the recent COVID-19 pandemic, which forced many businesses to switch to digital channels. Leadership’s openness to new technologies and research collaborations is essential for continuous improvement and adaptation in the dynamic business landscape. The willingness to innovate and upgrade product offerings to meet online market standards is a clear differentiator among community enterprises.

Despite the strengths, there are areas needing enhancement. Production planning, particularly under organic farming standards, requires more attention. Additionally, marketing plans must be flexible and responsive to the unpredictable shifts in the marketing environment, as evidenced by recent global events like the pandemic. The enterprises that can swiftly adapt their strategies to include online channels are the ones that turn challenges into opportunities, expanding their consumer base beyond local and traditional markets.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Drawing from the study results and the project team’s engagement with community enterprises in rural areas in Thailand, the study has identified a set of strategic guidelines to develop the vacuum-packed rice business’s value chain. One of the strategies involves refining the product and brand, wherein improving the product’s core features for the commercial market is essential. Ensuring authenticity and quality entails improving packaging and brand identity, establishing a traceability system, increasing customer trust, and opening up new markets. Also, leveraging local knowledge and market insights to innovate and develop new products is essential. This should involve iterative testing with consumers to refine prototypes before launching them in the marketplace, ensuring that these new offerings resonate with and meet consumer demands. While embracing digital transformation through online marketplaces and building a robust marketing network in collaboration with educational institutions is beneficial.

Consequently, nurturing community retail outlets and green markets can serve dual purposes, such as sales venues and knowledge exchange hubs connecting producers with consumers. Developing digital tools like mobile applications for rice production databases and financial tracking can significantly improve decision-making in production planning, enhancing efficiency and responsiveness to market changes. While creating a diverse range of public relations materials from traditional print to dynamic digital media can increase the visibility and reputation of community enterprises showcasing their commitment to quality and sustainability. In addition, conducting knowledge transfer sessions and practical workshops will help strengthen the capabilities of community enterprises, equipping them with the skills and knowledge required for sustainable growth and innovation.

Community enterprises are advised to leverage empirical sales data from organically produced rice to broaden their online and physical sales channels, aligning with evolving consumer behaviors. Rigorous production planning should be pursued to maintain safety standards and continued product development, like rice berry flour and rice cereal. Seeking certifications like FDA approval can further reinforce consumer confidence in the product quality community enterprises offer. The project’s guidance across CBE case study areas should foster the formation of structured networks, such as the Rice Safety Community Enterprise Network (RSCEN), to achieve greater scale and impact. This involves more than just aggregating production and marketing efforts. It entails a holistic approach to value chain development, empowering CBEs with the skills and knowledge to manage their operations effectively, adopt new technologies, and navigate market complexities. This could involve training programs on financial management, marketing strategies, quality control, and sustainable agriculture practices. Collectively exploring and accessing new markets domestically and internationally through joint marketing efforts, trade fairs, and online platforms. This can expand the reach of CBE products and increase their bargaining power.

In addition, collaboration among CBEs should be promoted to develop innovative products and services that meet evolving consumer demands. This could involve creating value-added products like organic rice snacks or ready-to-eat meals and exploring new marketing channels like e-commerce and direct-to-consumer sales. These strategies should be adaptable and tailored to each CBE’s specific needs and capacities. This requires a flexible and participatory approach that recognizes the diversity of CBEs and empowers them to make decisions aligned with their local context and priorities. By working collaboratively and adapting strategies to local needs, CBEs can uplift their value chains, enhance their competitiveness, and contribute to the sustainable development of the local rice industry.

Acknowledgment

This study is an integral component of the research project titled ‘The potential development and value chain enhancement of high-value products from rice community enterprise in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand’. We sincerely thank the Program Management Unit for Area-Based Development (PMU-A) for their financial support under the Flagship Initiative Plan of the Year 2020, Local Developing Universities [grant no: A13F630015].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aggarwal, P., & Manaswi, K. (2022). Role of circular economy, industry 4.0 and supply chain management for tribal economy: A systematic review. Journal of the Anthropological Survey of India, 71(2), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277436X221125914

- Amekawa, Y. (2013). Can a public GAP approach ensure safety and fairness? A comparative study of Q-GAP in Thailand. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(1), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.746958

- Amnuaylojaroen, T., Chanvichit, P., Janta, R., & Surapipith, V. (2021). Projection of rice and maize productions in Northern Thailand under climate change scenario RCP8.5. Agriculture, 11(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11010023

- Appiah, D. O. (2019). Climate policy research uptake dynamics for sustainable agricultural development in Sub-Saharan Africa. GeoJournal, 85(2), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-09976-2

- Baird, I. G. (2024). Going organic: Challenges for government-supported organic rice promotion and certification nationalism in Thailand. World Development, 173, 106421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106421

- Battistella, C., De Toni, A. F., De Zan, G., & Pessot, E. (2017). Cultivating business model agility through focused capabilities: A multiple case study. Journal of Business Research, 73, 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.12.007

- Békés, G., & Kézdi, G. (2021). Data analysis for business, economics, and policy. Cambridge University Press.

- British Council. (2020). The state of social enterprise in Thailand (Global Social Enterprise). https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/state_of_social_enterprise_in_thailand_2020_final_web.pdf.

- Brown, G., Kangas, K., Juutinen, A., & Tolvanen, A. (2017). Identifying environmental and natural resource management conflict potential using participatory mapping. Society & Natural Resources, 30(12), 1458–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2017.1347977

- Burdon, D., Potts, T., Barnard, S., Boyes, S. J., & Lannin, A. (2022). Linking natural capital, benefits and beneficiaries: The role of participatory mapping and logic chains for community engagement. Environmental Science & Policy, 134, 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.04.003

- Cavite, H. J., Kerdsriserm, C., & Suwanmaneepong, S. (2021). Strategic guidelines for community enterprise development: A case in rural Thailand. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 17, 284–304. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-05-2021-0062

- Chand, N., Kerr, G. N., & Bigsby, H. (2015). Production efficiency of community forest management in Nepal. Forest Policy and Economics, 50, 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2014.09.001

- Constantinides, E. (2006). The Marketing Mix Revisited: Towards the 21st Century Marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 22(3–4), 407–438. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725706776861190

- Contini, C., Gabbai, M., Zorini, L. O., & Pugh, B. (2012). Participatory scenarios for exploring the future: insights from cherry farming in South Patagonia. Outlook on Agriculture, 41(2), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.5367/oa.2012.0086

- Dana, L. P. (2010). Nunavik, Arctic Quebec: Where cooperatives supplement entrepreneurship. Global Business and Economics Review, 12(1/2), 42–71. https://doi.org/10.1504/GBER.2010.032317

- Dana, L.-P., Gurău, C., Hoy, F., Ramadani, V., & Alexander, T. (2021). Success factors and challenges of grassroots innovations: Learning from failure. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 164, 119600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.03.009

- Dana, L.-P., Sharma, N., Kumari, S., Tripathy, K. K., Pillai, B. P., & Jayalakshmi, R. (2023). Cooperatives as a catalyst for sustainability: Lessons learned from Asian models (Vol. 12). World Scientific. https://doi.org/10.1142/12764.

- Defoer, T., De Groote, H., Hilhorst, T., Kanté, S., & Budelman, A. (1998). Participatory action research and quantitative analysis for nutrient management in southern Mali: A fruitful marriage? Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 71(1), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(98)00142-X

- Devaux, A., Velasco, C., Ordinola, M., & Naziri, D. (2020, The potato crop: Its agricultural, nutritional and social contribution to humankind (pp. 75–106). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28683-5_3

- Faysse, N., Phiboon, K., & Purotaganon, M. (2022). Which pathway to address interrelated challenges to farm sustainability in Thailand? Views of local actors. Regional Environmental Change, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-021-01871-2

- Goodwin, B. K., & Mishra, A. K. (2004). Farming efficiency and the determinants of multiple job holding by farm operators. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 86(3), 722–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0002-9092.2004.00614.x

- Graef, F., Sieber, S., Mutabazi, K., Asch, F., Biesalski, H. K., Bitegeko, J., Bokelmann, W., Bruentrup, M., Dietrich, O., Elly, N., Fasse, A., Germer, J. U., Grote, U., Herrmann, L., Herrmann, R., Hoffmann, H., Kahimba, F. C., Kaufmann, B., Kersebaum, K.-C., … Uckert, G. (2014). Framework for participatory food security research in rural food value chains. Global Food Security, 3(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2014.01.001

- Hausmann, R., Hwang, J., & Rodrik, D. (2007). What you export matters. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-006-9009-4

- Jeenaboonrueang, S. (2019). Sufficiency economy philosophy: A way towards business sustainability. Journal of Management Science Chiangrai Rajabhat University, 13(2). https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jmscrru/article/view/122701.

- Joiner, J., & Okeleke, K. (2019). E-commerce in agriculture: New business models for smallholders’ inclusion into formal economy. GSMA. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/E-commerce_-in_agriculture_new_business_models_for_smallholders_inclusion_into_the_formal_economy.pdf.

- Kapoor, I. (2001). Towards participatory environmental management? Journal of Environmental Management, 63(3), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1006/jema.2001.0478

- Kasem, S., & Thapa, G. B. (2012). Sustainable development policies and achievements in the context of the agriculture sector in Thailand. Sustainable Development, 20(2), 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.467

- Kitipadung, J., & Jaiborisudhi, W. (2023). Community enterprise in processed agricultural products after the covid-19: Problems and adaptation for the development of grassroots economy. WSEAS TRANSACTIONS ON BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS, 20, 573–585. https://doi.org/10.37394/23207.2023.20.53

- Koshy, N. S., Jagadeesh, K., Govindan, S., & Sami, N. (2021). Middlemen versus middlemen in agri-food supply chains in Bengaluru, India: Big data takes a byte. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 127, 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.11.013

- Kumnerdpet, W., & Sinclair, A. J. (2011). Implementing participatory irrigation management in Thailand. Water Policy, 13(2), 265–286. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2010.089

- Laiprakobsup, T. (2018). Leadership, trust, proximity to government, and community-based enterprise development in rural Thailand. Asian Geographer, 35(1), 53–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10225706.2017.1422767

- Lamey, L., Deleersnyder, B., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Dekimpe, M. G. (2018). New product success in the consumer packaged goods industry: A shopper marketing approach. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 35(3), 432–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2018.03.001

- Liu, L., Ross, H., & Ariyawardana, A. (2023). Building rural resilience through agri-food value chains and community interactions: A vegetable case study in Wuhan, China. Journal of Rural Studies, 101, 103047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2023.103047

- Llones, C., Mankeb, P., Wongtragoon, U., & Suwanmaneepong, S. (2021). Bonding and bridging social capital towards collective action in participatory irrigation management. Evidence in Chiang Rai Province, Northern Thailand. International Journal of Social Economics, 49(2), 296–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-05-2021-0273

- Llones, C. A., Mankeb, P., Wongtragoon, U., & Suwanmaneepong, S. (2022). Production efficiency and the role of collective actions among irrigated rice farms in Northern Thailand. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 20(6), 1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2022.2047464

- Moore, J. D., & Donaldson, J. A. (2023). Going green in Thailand: Upgrading in global organic value chains. Journal of Agrarian Change, 23(4), 844–867. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12543

- MOTS. (2022). Thailand tourism strategy for post-pandemic era (pp. 1–11). https://www.jttri-airo.org/en/dll.php?id=67&s=pdf2&t=apers.

- Neef, A., Ekasingh, B., Friederichsen, R., Becu, N., Lippe, M., Sangkapitux, C., Frör, O., Punyawadee, V., Schad, I., Williams, P. M., Schreinemachers, P., Neubert, D., Heidhues, F., Cadisch, G., The Dang, N., Gypmantasiri, P., & Hoffmann, V. (2013). Participatory Approaches to Research and Development in the Southeast Asian Uplands: Potential and Challenges. In H. L. Fröhlich, P. Schreinemachers, K. Stahr, & G. Clemens (Eds.), Sustainable land use and rural development in Southeast Asia: Innovations and policies for mountainous areas (pp. 321–365). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-33377-4_9

- Nyam, Y. S., Kotir, J. H., Jordaan, A. J., Ogundeji, A. A., & Turton, A. R. (2020). Drivers of change in sustainable water management and agricultural development in South Africa: A participatory approach. Sustainable Water Resources Management, 6(4), 62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-020-00420-9

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2013). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. Wiley&Sons.

- Peredo, A. M., & Chrisman, J. J. (2006). Toward a theory of community-based enterprise. The Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208683

- Pradhan, S., & Samanta, S. (2022). Global research on community-based enterprise: A bibliometric portrait. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 17(4), 793–814. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-01-2022-0010

- Saboori, B., Alhattali, N. A., & Gibreel, T. (2023). Agricultural products diversification-food security nexus in the GCC countries; introducing a new index. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 12, 100592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2023.100592

- Saija, L., & Pappalardo, G. (2022). An argument for action research-inspired participatory mapping. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 42(3), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18817090

- Salamzadeh, A., & Dana, L. P. (2021). The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: Challenges among Iranian startups. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 33(5), 489–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2020.1821158

- Sitabutr, V., Deebhijarn, S., Sitabutr, V., & Deebhijarn, S. (2017). Community-based enterprise export strategy success: Thailand’s OTOP branding program. https://doi.org/10.22004/AG.ECON.264706.

- Soaga, J. A., & Makinde, E. (2014). The role of community based forest enterprises in rural dwellers welfare at eriti community in Ogun State, Nigeria. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 24(2), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1018529120140207

- Srisathan, W. A., Ketkaew, C., & Naruetharadhol, P. (2023). Assessing the effectiveness of open innovation implementation strategies in the promotion of ambidextrous innovation in Thai small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 8(4), 100418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2023.100418

- Sulistyaningsih, C. R., & Wisnujati, N. S. (2020). The effect of product quality, prices, and consumer knowledge levels on product and socio-economic status on organic rice customer satisfaction in Klaten, Central Java (pp. 147–150). https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.201017.034

- Suwanmaneepong, S., Kerdsriserm, C., Lepcha, N., Cavite, H. J., & Llones, C. A. (2020). Cost and return analysis of organic and conventional rice production in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand. Organic Agriculture, 10(3), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-020-00280-9

- Suwanmaneepong, S., Kultawanich, K., Khurnpoon, L., Sabaijai, P. E., Cavite, H. J., Llones, C., Lepcha, N., & Kerdsriserm, C. (2023). Alternate Wetting and Drying as Water-Saving Technology: An Adoption Intention in the Perspective of Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) Suburban Rice Farmers in Thailand. Water, 15(3), 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15030402

- Swash, T. (2007). Enterprise, diversity and inclusion: A new model of community-based enterprise development. Local Economy, 22(4), 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690940701736835

- Tan, G. N. D. (2021). A business-model approach on strategic flexibility of firms in a shifting value chain: The case of coffee processors in Amadeo and Silang, Cavite, Philippines. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-020-00255-5

- Tantoh, H. B., Simatele, D. M., Ebhuoma, E., Donkor, K., & McKay, T. J. M. (2021). Towards a pro-community-based water resource management system in Northwest Cameroon: Practical evidence and lessons of best practices. GeoJournal, 86(2), 943–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-10085-3

- Teng, C.-C., & Wang, Y.-M. (2015). Decisional factors driving organic food consumption: Generation of consumer purchase intentions. British Food Journal, 117(3), 1066–1081. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2013-0361

- Toiba, H., Efani, A., Rahman, M. S., Nugroho, T. W., & Retnoningsih, D. (2022). Does the COVID-19 pandemic change food consumption and shopping patterns? Evidence from Indonesian urban households. International Journal of Social Economics, 49(12), 1803–1818. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-11-2021-0666

- Ubilava, D., & Foster, K. (2009). Quality certification vs. product traceability: Consumer preferences for informational attributes of pork in Georgia. Food Policy, 34(3), 305–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2009.02.002

- Veisi, H., Carolan, M. S., & Alipour, A. (2017). Exploring the motivations and problems of farmers for conversion to organic farming in Iran. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 15(3), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2017.1312095

- Verhofstadt, E., & Maertens, M. (2013). Processes of modernization in horticulture food value chains in Rwanda. Outlook on Agriculture, 42(4), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.5367/oa.2013.0145

- Wang, H. H., Chen, J., Bai, J., & Lai, J. (2018). Meat packaging, preservation, and marketing implications: Consumer preferences in an emerging economy. Meat Science, 145, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.06.022

- Welsch, H. P., & Kuhns, B. A. (2002). Community-based enterprises: Propositions and cases. An entrepreneurial Bonanza (pp. 17–20). California Urban Partnership.

- Wentworth, C., Arroyo, M. T., Lembi, R. C., Feingold, B. J., Freedman, D., Gray, S., Hodbod, J., Jablonski, B. B. R., Janda-Thomte, K. M., Lemoine, P., Nielsen, A., Romeiko, X. X., Salvo, D., Olabisi, L. S., van den Berg, A. E., & Yamoah, O. (2024). Navigating community engagement in participatory modeling of food systems. Environmental Science & Policy, 152, 103645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2023.103645

- Wu, W. (2019). Estimation of technical efficiency and output growth decomposition for small-scale rice farmers in Eastern India A stochastic frontier analysis. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-05-2019-0072

- Xie, Z., Wang, J., & Miao, L. (2021). Big data and emerging market firms’ innovation in an open economy: The diversification strategy perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121091

- Zhou, J., Jin, Y., & Liang, Q. (2022). Effects of regulatory policy mixes on traceability adoption in wholesale markets: Food safety inspection and information disclosure. Food Policy, 107, 102218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102218