ABSTRACT

Knowledge transfer initiatives aim to improve farmers’ knowledge and skills for tackling the growing economic, environmental and social challenges in agriculture. However, their evaluation is often inadequate due to institutional barriers and a lack of comprehensive methodology for assessing normative and behavioural shifts within this social group. To address this gap, we developed an extended evaluation framework for the knowledge transfer activities within the European Union's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), including three indicators levels: output, result and impact. The indicators and survey instruments were based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour and piloted in a selected EU Member State for evaluating knowledge transfer measures in the programming period 2014–2022. The results indicate a promising potential of the proposed framework for capturing the multifaceted outcomes of knowledge transfer activities in agriculture. The usefulness and feasibility of the evaluation framework were further assessed through interviews with AKIS actors. They highlighted that evaluation activities at the Member State level may be hindered by inconsistent long-term data collection, insufficient response and involvement of farmers, deviations from the agreed protocols and a lack of dedicated resources. To ensure the uptake of the proposed evaluation framework, evaluation culture within the managing authorities and among stakeholders should be systematically fostered at the Member State level. This process can be enhanced by adopting a more elaborated CAP monitoring framework and methodology guidelines and by providing targeted training on evidence-driven policy-making.

1. Introduction

Agriculture faces an increasing range of challenges arising from social, environmental, political, economic and technological changes. To recognize and effectively respond to these challenges, farmers must be equipped with the latest knowledge and novel skills, which often go beyond the scope of primary agricultural production (Faure et al., Citation2012). Many governments are thus providing information-sharing and advisory support through various agricultural policy instruments. For example, the European Union's (EU) Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) provides funding for research, innovation, advisory services and training for farmers (ENRD, Citation2019). Similarly, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) funds knowledge-sharing initiatives through the Cooperative Extension System (CES) (Wang, Citation2014), and Australia's Rural Research and Development Corporations have established public-private partnerships to promote innovation and knowledge transfer in the agricultural sector (Paschen et al., Citation2017). Moreover, new approaches to farmer training are being developed, emphasizing the importance of practical skills, field demonstrations and participatory approaches for farmers’ successful adoption of sustainable agricultural practices (Bourne et al., Citation2021; Knook & Turner, Citation2020).

However, the assessment of knowledge transfer initiatives within the CAP remains limited, especially compared to other more prominent and financially extensive policy interventions, such as investment support and agri-environmental measures (ECA, Citation2015; Hill et al., Citation2017). This is a drawback as evaluation is a crucial component of the policy cycle, enabling the assessment of the policy's effectiveness and informing future decision-making (Cairney, Citation2019). Various approaches and theories have been developed to guide the design of evaluations for specific contexts (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2011). One such is theory-based evaluation (Chen, Citation1990; Weiss, Citation1997), which assesses the effectiveness of interventions, policies or programs by focusing on their underlying theories of change and explaining the logical model between their objectives and measures. Furthermore, it aims to analyse the expediency of the actions taken to achieve the objectives and the intended outcomes (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2011).

The EU's structural policies, such as the CAP and cohesion policy, consistently use the intervention logic approach to illustrate the relationships between proposed interventions and their intended outcomes (Gaffey, Citation2013). The policy interventions are illustrated through a logic model (Grinnell et al., Citation2016), which identifies the relationships between inputs, activities, outputs and immediate outcomes, as well as longer-term impacts. The assumed cause-impact relationships are measured by the indicators, which assess whether the program is achieving its intended objectives and doing so as expected based on the underlying theory (Harmelink et al., Citation2008). The EU's intervention logic uses a three-level indicator framework, which includes output, result and impact indicators. Output indicators refer to the direct goods and services delivered by the policy activities, while result indicators assess the immediate effects of the policy on the target population or beneficiaries. On the other hand, impact indicators measure the broader and long-term effects on society and the environment (EC, Citation2017).

In practice, intervention logic models and evaluation frameworks often lack clarity and quality in their design (Donaldson et al., Citation2019; Harmelink et al., Citation2008; Šumrada et al., Citation2020). For example, within the CAP evaluation framework, knowledge transfer is currently relatively weakly defined (EC, Citation2022; ECA, Citation2015), offering a limited list of indicators, which primarily focus on measuring interventions’ descriptive and quantitative inputs and outputs, such as the number of trainings implemented and the number of participating farmers. However, higher-level indicators that should capture normative and behavioural outcomes of knowledge transfer initiatives, such as farmers’ values and knowledge, technology adoption and agricultural performance, have been rarely considered (EC, Citation2022; ECA, Citation2015; Prager et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, the involvement of beneficiaries, i.e. farmers, in the evaluation process is becoming imperative (ECA, Citation2015) as their engagement can enhance the quality of policy planning procedures and foster a stronger sense of ownership, which can lead to increased adoption rates and improved efficiency of measures (Luján Soto et al., Citation2021; Masset & Haddad, Citation2015).

For a theory-based evaluation approach, it is fundamental to align policy theory with established behavioural or social theories (Stewart I. Donaldson Citation2007). The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991) is frequently employed in educational research (e.g. Hollett et al., Citation2020; Skoglund et al., Citation2020) and for explaining farmers’ decision-making processes and behaviour (e.g. Rezaei et al., Citation2019). It can also serve as a conceptual framework for evaluating policy interventions in agriculture (Wauters et al., Citation2010), where it can be used to analyse their effects and to identify the reasons for their success or failure (Ajzen, Citation2011). However, despite its relatively frequent use in the studies of farmers’ behaviour (Sok et al., Citation2021), it has not yet been widely applied to evaluate knowledge transfer in agriculture (Hall et al., Citation2019).

Scientific research on knowledge transfer in agriculture is relatively well-established in developing countries (Danso-Abbeam, Citation2022; Giulivi et al., Citation2023; Rajalahti & Swanson, Citation2010). However, such evaluations are relatively rare in developed countries and Europe (Faure et al., Citation2012; OECD, Citation2015). The main focus of these studies is on the impacts of knowledge transfer on farm management and performance (Cawley et al., Citation2018; Dinar et al., Citation2007) and on the uptake of specific farming practices (Alif et al., Citation2024; Ingram et al., Citation2022; Nordin & Höjgård, Citation2017). Some evaluations also focused on assessing the governance structures, capacity, management and methods involved in the knowledge transfer system (Lioutas et al., Citation2019; Prager et al., Citation2017). However, there continues to be a lack of comprehensive theory-based evaluations of knowledge transfer policies, which would connect inputs and outputs of the interventions with higher-level indicators assessing the immediate and long-term effects on beneficiaries.

Our study aims to develop a systematic evaluation framework and methodology to assess the effectiveness of knowledge transfer interventions in agriculture. It expands the current CAP monitoring and evaluation system by specifically focusing on result and impact indicators and engaging farmers in the evaluation process. We build on the Theory-based approach (Chen, Citation1990; Weiss, Citation1997) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991) to develop a comprehensive set of indicators and suitable survey instruments and pilot them in Slovenia, a Central European EU Member State. Finally, we explore the feasibility and potential challenges that may arise while implementing the developed framework in practice by interviewing representatives of the Slovenian Agricultural Knowledge and Innovations System (AKIS).

2. Case study description

Slovenia is a Central European country and an EU Member State since 2004. Given its predominantly hilly or karst landscape and alpine and continental climate, permanent grasslands cover 57% of agricultural land. Livestock farming, particularly cattle, is a prevailing farming sector, with 66% of agricultural holdings engaging in it (Bedrač et al., Citation2023). Despite accelerated structural changes in recent decades, Slovenian agriculture still grapples with relatively low productivity compared to other EU countries and a predominantly small farm structure with an average farm size of 7 ha of agricultural land (Bedrač et al., Citation2023). The average age of Slovenian farmholders is 58 years (SURS, Citation2020). Additionally, the educational structure of Slovenian farmers is rather unfavourable, as more than half of farmholders (52%) possess only practical experience in agriculture, while only 10% have formal agricultural education at the secondary or higher level (SURS, Citation2020).

In Slovenia, the key systemic support for knowledge transfer is implemented through the Public Agricultural Advisory Service, a central organization for agricultural advisory operating at the regional and local levels (JSKS, Citation2023). It offers advisory support to farm holdings in various fields, including agricultural production, agri-environment, legal and tax issues, and CAP subsidy and investment support. In addition, knowledge transfer activities are supported as part of the CAP's Rural Development Policy (RDP). During the 2014–2022 programming period, these were promoted through training programs for farmers enrolled in Agri-environmental-climate measures (AECM), Organic farming (OF) and Animal welfare (AW), as well as Cooperation measures, which funded pilot and European Innovation Partnership (EIP) projects aimed at fostering cooperation between different actors in agriculture and related sectors (MKGP, Citation2021).

3. Methodology

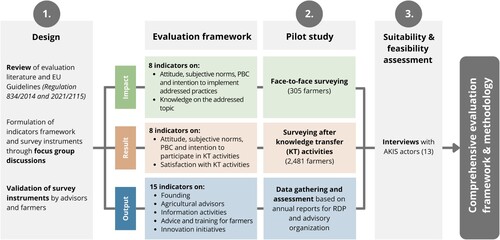

The study followed a three-phase structure (). The first phase involved the design of a comprehensive evaluation framework, which included indicators and survey instruments to assess outputs, results, and long-term impacts of knowledge transfer interventions in agriculture. Next, the evaluation framework was piloted in the case of knowledge transfer initiatives in Slovenian agricultural policy. The final phase included a qualitative assessment of the suitability and feasibility of the proposed framework by conducting interviews with the representatives of the Slovenian AKIS.

Figure 1. Research design for the development of an evaluation framework for the knowledge transfer initiatives within the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

3.1. Design of the evaluation framework and survey instruments

The EU's monitoring and evaluation framework for CAP interventions, including those aimed at facilitating knowledge and innovation transfer, establishes standardized indicators across output, result, and impact levels (EC, Citation2017; Regulation Citation2021/2115). Our evaluation framework aimed to align with and build upon these guidelines, thus, our indicator development process began by reviewing those for 2014–2022 (Regulation 834/Citation2014) and the 2023–2027 CAP programming period (Regulation, Citation2021/2115), along with relevant literature assessing knowledge transfer and advisory programs (e.g. ECA, Citation2015; Knierim et al., Citation2017; Prager et al., Citation2017).

Further, the framework and survey instruments for measuring indicators on the result and impact level were formulated and verified through several focus group sessions. The first session in June 2021 involved three representatives from the Slovenian Ministry of Agriculture and seven from the Public Agricultural Advisory Service (JSKS). We discussed the goals of the Slovenian knowledge transfer system and the needs, challenges and suggestions for designing its evaluation framework. Next, throughout the summer of 2021, we organized four sessions to design the survey instruments with six experts in knowledge transfer and agricultural economics. This step involved formulating constructs with associated statements for each envisaged indicator. In September 2021, we reconvened representatives from the ministry and JSKS to review the final set of indicators and survey instruments. In addition, five agricultural advisors with good knowledge of the sampling population were consulted to ensure the overall quality of the survey instruments regarding statement wording and clarifications. Finally, we pre-tested the survey for assessing result indicators with 15 farmers and the survey for impact indicators with 29 farmers.

The evaluation framework in the presented pilot study was applied to the knowledge transfer initiatives promoting agri-environmental practices. However, when designing it, we aimed to make it applicable with minor adjustments across diverse knowledge transfer topics and interventions.

3.1.1. Output indicators

Output indicators were developed in line with the requirements of the EU monitoring and evaluation framework (EC, Citation2017; Regulation Citation2021/2115). The process involved categorizing the indicators of the 2014–2022 (Regulation 834/2014) and 2023–2027 CAP program period (Regulation Citation2021/2115) into five thematic categories: public funding for knowledge transfer activities, agricultural advisors, dissemination of knowledge through various information sources, number of advice and training for farmers, and knowledge exchange and innovation initiatives, such as the European Innovation Partnership (EIP) projects ().

Table 1. The structure of the evaluation framework for the knowledge transfer system promoting agri-environment practices within the EU's Common Agricultural Policy.

3.1.2. Result and impact indicators

When designing the survey instruments, we drew upon the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1991) to gauge result and impact indicators, aiming to capture the effects of knowledge transfer initiatives, such as shifts in normative and behavioural aspects (EC, Citation2022; ECA, Citation2015). The TPB provides a valuable lens for predicting an individual's intention to engage in a specific behaviour by considering three behavioural and social factors: the individual's positive or negative assessment of engaging in a specific behaviour (attitudes toward the behaviour), perceived social pressure to engage in the behaviour (subjective norms), and perceived ease or difficulty to perform the behaviour (perceived behavioural control, PBC) (Fishbein and Ajzen, Citation2010). To comprehensively evaluate knowledge transfer activities, we expanded the TPB constructs with additional theoretical elements where required (Ajzen, Citation1991) ().

The survey instrument for measuring result indicators (hereinafter: ‘results survey’) is provided in the Appendix, Table A1. It is designed to be conducted after knowledge transfer activities, such as training sessions, demonstration events, individual advice and participatory sessions. A departure from the standard evaluation approach is particularly evident in the part that probes respondents’ attitudes, subjective norms, PBC, and intentions towards participating in such activities. Additionally, the survey assesses respondents’ satisfaction with the activity they attended, including their satisfaction with presenters or moderators, organization and content (Gopal et al., Citation2021). Respondents rate statements using a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from strongly disagree ( = 1) to strongly agree ( = 7). The survey also gathers demographic details (i.e. respondents’ gender, age, education and household income) and farm characteristics (i.e. location, production focus, engagement in agricultural policy measures and the farm's prospects).

The survey instrument for measuring impact indicators (hereinafter: ‘impacts survey’) is presented in the Appendix, Tables A2 and A3. It is designed to be conducted on a general population of farmers, as it aims to assess the broader impacts of knowledge transfer, including its diffusion on non-beneficiaries (Bonan & Pagani, Citation2018; Kreft et al., Citation2023). A distinctive feature of this survey is a short test with multiple-choice questions, which measures farmers’ objective knowledge. In the case of the pilot presented in this study, the test was on the following topics: agri-environmental practices and their impact on the environment; agri-environmental measures (AEMs) and their requirements; and nature and farmland species identification (Appendix, Table A2). The second part of the survey includes TPB-based questions regarding implementing practices of interest, in our case, the practices promoting agri-environmental practices, using statements with a 7-point Likert-type scale response. The following part aims at quantifying the impact of knowledge transfer initiatives on farmers’ behaviour, and it includes questions regarding farmers’ intention to implement an array of agri-environmental practices, their intention to valorize agri-environmental efforts on their farm, to acquire knowledge on agri-environmental topics, and their intention to participate in the AEMs. Finally, the concluding section features demographic and farm characteristics queries similar to the results survey.

3.2. Pilot study

3.2.1. Output indicators

The output indicators were piloted by assessing their values for the Slovenian agricultural policy in 2020. For this assessment, we reviewed relevant sources of policy implementation, including annual reports detailing the implementation of the RDP in the 2014–2022 programming period (MKGP, Citation2021) and reports from the JSKS (JSKS, Citation2021).

3.2.2. Result indicators

The pilot study for result indicators was carried out between December 2021 and January 2022 within the context of mandatory annual training for farmers participating in the AECM and OF measures. The training lasted four to six hours and was provided by the Slovenian public advisory service. The content of the training encompassed the conditions and requirements for implementing measures. In addition, the OF training included topics on water and soil conservation, organic beekeeping, seed cultivation, and marketing of organic products, and the AECM training covered landscape features and climate-smart agriculture (KGZS, Citation2021).

For the 27 online training sessions, all participating farmers were subsequently invited to partake in the online survey. In the case of seven in-person training sessions, printed surveys were distributed by agricultural advisors upon the conclusion of the training. Participants in both settings were appropriately informed about the research's purpose, ensured anonymity, and informed about data storage procedures. Specific ethics approval for this study was not required nor obtained. Of the 8,150 farms enrolled in the AECM and OF measures, all of which were obligated to undergo the training, the survey was answered by 2,873 farmers (35.3%), comprising 2,618 (91%) online and 255 printed surveys. Before conducting statistical analyses, questionnaires with more than 20% missing data were excluded. Additionally, we excluded ‘protest’ questionnaires where all answers were identical or if respondents did not recognize negative statements. The final sample comprised 2,481 surveys (86,4% of the initial respondents’ pool) ().

Table 2. Socio-economic profile of survey respondents for result and impact indicators.

Indicator assessment relied on calculating the median of responses within each construct, reflecting the specific indicator. Indicator values thus can range from 1 to 7, with 1 indicating a highly unfavourable state and 7 representing an exceptionally favourable one. Visualization of outcomes was facilitated using boxplots.

3.2.3. Impact indicators

The impact survey targeted a sample population comprising all farmers registered in the Slovenian Ministry of Agriculture's Register of Farm Holdings, making them eligible for CAP support. The pilot surveying was conducted at two regional public agricultural advisory offices during March and April 2022. Participation invitations were sent to all farmers who had submitted an annual application for CAP Pillar I direct payments at these specified units within the designated survey period. Due to the length and complexity of the survey, the surveying process was facilitated by trained interviewers who assisted respondents in navigating the questionnaire, ensuring reliability and coherence in their responses. In addition, the interviewers ensured that respondents were well informed about the research's objectives and anonymity guarantees and obtained voluntary consent to participate. A total of 305 farmers completed the survey ().

Similarly to the result indicators, the statistical analysis involved calculating medians within each survey construct, corresponding to each indicator. Later, these distributions were visually represented with boxplots. The assessment of the indicator on knowledge (I_24) was calculated as an average score of correct answers of all respondents; thus, the indicator can range from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating a highly unfavourable state (meaning all respondents would answer on average all questions wrongly) and 10 representing an exceptionally favourable one (meaning all respondents would answer on average all questions correctly). Descriptive and quantitative analyses were performed using Excel (Microsoft, version 10) and R software (R Core Team, version 4.0.2).

3.3. Interviews with AKIS actors

Interviews were conducted with the 13 representatives of the AKIS actors to assess the suitability and feasibility of the proposed evaluation framework. The interviewees represented government bodies, agricultural advisory services, research institutions, and evaluation firms.

The semi-structured interview began with questions regarding the role of knowledge transfer in agriculture and its current evaluation approach. Next, the interviewer ensured a comprehensive presentation of the proposed evaluation framework, followed by an assessment discussion based on the following criteria (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2011; Lipicer et al., Citation2009): (1) relevance (alignment of acquired information with the policy context and needs); (2) usefulness of the results in practice; (3) suitability (alignment with the established legal foundations); and (4) feasibility considering the required resources and efforts.

The interviews were conducted in the spring of 2023, ranging from 50 to 110 minutes. Each recording was transcribed, followed by multiple readings and a coding process (Saldana, Citation2015). During this process, relevant segments were assigned a specific code. Text segments sharing the same code were grouped and differentiated from those under different codes. Next was the phase of text organization, combining semantically related text or codes. The coding process facilitated a reduction in data volume and enabled the connection of fragmented meanings of the research topic into semantically and contextually coherent wholes. The reconstruction of the obtained data into new, complete units enabled a deeper understanding of the data. The interviews were analysed using ATLAS.ti (Cleverbridge, version 8).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Pilot study results

4.1.1. Output indicators

The developed evaluation framework aims to assess the effectiveness of knowledge transfer measures on three indicator levels: outputs, results and impacts. In total, the framework includes 31 main indicators (). On the output level, the proposal suggests annual monitoring with indicator structure remaining in the scope of guidelines of 2014–2022 (Regulation 834/2014) and the 2023–2027 CAP programming period (Regulation, Citation2021/2115). The results of the pilot study are presented in Appendix, Table A4.

The budget for knowledge transfer interventions during the 2014—2020 period was relatively low, consisting of only 0.82% of the Slovenian RDP funding, which is below the European average (3.63%) (Beck et al., Citation2021) and the target value for Slovenia (3.90%) (ENRD, Citation2016). A significant portion of these funds (66.40%) was spent on addressing agri-environmental topics, which reflects the importance of improving farmers’ understanding of the agri-environmental objectives. However, the limited overall budget for knowledge transfer probably limits its potential reach and effectiveness (Erjavec et al., Citation2018).

There is a noticeable lack of advisors and their training in the field of agri-environment. The average advisor-to-farmer ratio is one advisor per 170 farms. In comparison, other European countries’ public advisory systems exhibit a lower ratio, averaging just above 100 farmers per advisor, while private advisory organizations have a ratio of around 50 (Knierim et al., Citation2017). This indicates a potential strain on advisors’ capacity to provide adequate support, particularly personalized one-on-one support. Furthermore, there is a limited amount of training for advisors. For example, in 2020, only five training sessions were organized on agri-environmental topics; even then, these topics were indirectly covered. Advisors’ limited scope of expertise may present one of the important barriers (Ingram et al., Citation2022), as advisors may focus on administrative aspects rather than providing comprehensive support to farmers (Stupak et al., Citation2019).

Examining output indicators also highlights shortcomings regarding the methods employed to deliver knowledge to farmers. The training sessions were mainly in the form of relatively standard and generic lectures and, at the time of the analysis, did not include demonstration activities and other innovative knowledge transfer methods based on participatory and group approaches. This indicates a potential gap as these methods are well-known for enabling the utilization of novel and local knowledge, which is particularly valuable when addressing agri-environmental issues (Knook & Turner, Citation2020). The provision of individual advice represented an important approach to supporting the farmers. However, as indicated above, the question of the long-term quality of advisory service arises considering the limited capacity and lack of training of the agricultural advisors on several emerging topics in agriculture.

4.1.2. Result indicators

The evaluation of result indicators is proposed to be implemented after the knowledge transfer activities, such as training sessions, field demonstrations, individual advice or EIP projects. Evaluation should be carried out annually to monitor and assess participants’ satisfaction with the implementation of the measures and their immediate effects. To capture immediate effects effectively, the survey should be conducted promptly after the activity (Colquhoun et al., Citation2016), ensuring optimal participation while attendees are still available for feedback. Additionally, a follow-up assessment after a few months later can be considered to observe any changes in participants’ attitudes and intentions.

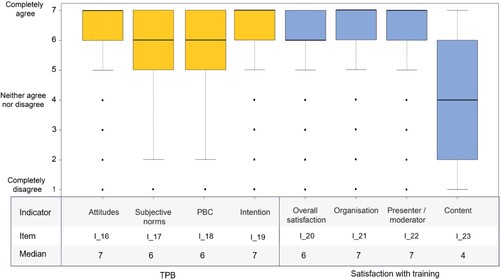

In our pilot study, we conducted a post-training assessment of the training for the farmers enrolled in the AECM and OF measures. The results further confirmed the inadequacies in the Slovenian knowledge transfer system in the agri-environmental field, which were indicated by the output indicators. While the participants expressed overall satisfaction with the training (rating 6 out of 7), the quality of the presenter (7) and the training organization (7), their satisfaction with the content of the training was moderate (4) (). Farmers noted that the training was too standardized and offered limited diversity in topics, which were repeated annually. They also highlighted the absence of field visits and innovative knowledge transfer tools and methods. This indicates a need for more tailored and site-specific advice (Oyinbo et al., Citation2019) and farmers’ preference for using field demonstrations and other group-based approaches over lectures delivered to a larger audience (Šumrada et al., Citation2022).

Figure 2. Boxplots of the result indicators measuring farmers’ normative and behavioural aspects regarding participation in agri-environmental training and their satisfaction with them (n = 2,467).

The indicators design based on the TPB revealed a positive attitude (7) and subjective norms (6) towards acquiring agri-environmental knowledge. Farmers also exhibited a relatively high ability to attend such trainings (6) and expressed a strong intention for further participation (7). These findings are consistent with prior studies (e.g. Thomas et al., Citation2020) and suggest that farmers engaged in the AEMs are receptive to acquiring agri-environmental knowledge.

4.1.3. Impact indicators

Impact indicators aim to assess knowledge transfer interventions’ long-term and broader effects. The proposed evaluation methodology suggests surveying a representative sample of the general population of farmers at regular intervals, such as every three years.

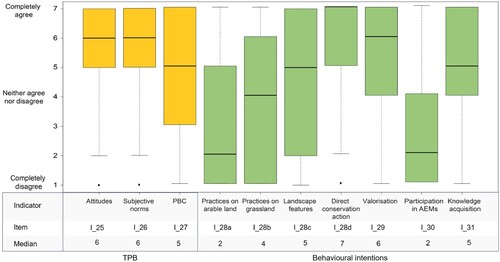

Farmers in our pilot study demonstrated a medium level of agri-environmental knowledge (rating 5 out of 10). Among the topics assessed, farmers are well aware of the agri-environmental practices and their environmental impact (7). On the other hand, their knowledge of the AEMs and their requirements was relatively poor (4). This finding may partially explain their low intention to participate in the AEMs, as previous research has shown that well-informed farmers are more likely to engage in such measures (Brown et al., Citation2020). Farmers’ knowledge about biodiversity and species identification was slightly higher (5). However, the relatively low results of the knowledge assessment indicate the importance of providing farmers with more information and training opportunities to enhance their understanding of local biodiversity, as this can positively affect the adoption of agri-environmental practices (Czajkowski et al., Citation2021).

Farmers generally displayed a positive attitude (rating 6 out of 7) and positive subjective norms (6) towards the environment and the implementation of agri-environmental practices (). Previous research shows that positive pro-environmental attitudes are typically associated with a higher likelihood of adopting agri-environmental practices (Tama et al., Citation2021) and enrolling in the AEMs (Brown et al., Citation2020). However, in our pilot study, these positive attitudes did not translate into an intention to implement such behaviours. The intention to participate in the AEMs was relatively low (rating 2 out of 7). Similarly, there was a relatively low intention to conduct voluntary practices related to biodiversity conservation on arable land (2) and grasslands (4). However, farmers demonstrated a moderate willingness to participate in the preservation of the landscape features (5) and a high intention to implement direct conservation actions (7), such as pesticide application practices that are friendly to pollinators and provide habitats for beneficial organisms (e.g. instalment of dry-stone walls, ponds, hotels for insects and bird nesting boxes).

Figure 3. Boxplots of impact indicators measuring farmers’ knowledge, attitude, and behavioural intention in the agri-environment field in 2022 (n = 305).

The relatively low interest in enrolling in the AEMs and implementing certain agri-environmental practices suggests that other behavioural factors may affect farmers’ decisions (Brown et al., Citation2020). Some reasons were indicated during the assessment of perceived behavioural control (PBC), which refers to individuals’ perceptions of their ability to engage in a behaviour. In the pilot study, farmers identified several constraints, including time and financial considerations and a lack of knowledge or technical skills. Furthermore, a significant constraint was the misalignment of agri-environmental practices with their existing farming practices and production goals. This aligns with previous research, indicating that farmers often prioritize production-related factors (Włodarczyk-Marciniak et al., Citation2020) and perceive environmental measures primarily as a means of achieving production and economic goals (Brown et al., Citation2020; Novak et al., Citation2022). Therefore, despite farmer's positive attitudes towards nature conservation, these attitudes alone are insufficient to motivate their adoption of agri-environmental practices on a large scale (Wąs et al., Citation2021).

Finally, the results of our pilot study showed that farmers had a moderate intention to acquire agri-environmental knowledge (rating 5 out of 7) (). This intention was lower compared to a similar one in the result survey regarding further participation in knowledge transfer activities, which could indicate a disparity in the motivation for knowledge acquisition between farmers participating in the result survey and those in the impact survey. However, this can be partly expected as the participants in the result study had all already been enrolled in the AEMs, whereas the sample in the impact survey intended to represent the general farming population. Farmers also displayed a relatively high level of intention (rating 6) to valorize the agri-environmental practices on their farms, e.g. by using their efforts to improve the market visibility of their farms or to achieve higher product prices. These highlight farmers’ potential economic and market-related motivations in embracing sustainable practices and their recognition of the added value they may bring.

The results of the evaluation pilot study shed light on the complexity of addressing farmers’ educational needs in the agri-environmental field in Slovenia. Farmers’ knowledge of environmentally sustainable practices, benefits, and supporting policy instruments can differ. Therefore, it is important to develop tailored and targeted interventions that consider specific knowledge gaps observed among different groups of farmers, regions, farming systems and contexts (Thomas et al., Citation2020). This calls for using a diverse range of knowledge transfer approaches and methods. In particular, incorporating participatory and demonstration activities seems promising (Alif et al., Citation2024; OECD, Citation2015) since these approaches can foster group learning and encourage the integration of local knowledge (Knook & Turner, Citation2020). In addition, the pilot shows the importance of providing training not only to farmers but also to advisors to enhance their capacity to deliver relevant and appropriate advice (Ingram et al., Citation2022; OECD, Citation2015). It is thus important to recognize the significance of knowledge transfer activities within the agricultural policy and allocate sufficient budgetary resources to support them (Erjavec et al., Citation2018).

4.2. Assessment of the evaluation framework

4.2.1. Relevance, usefulness and suitability

The interviews with Slovenian representatives of AKIS showed significant demand for a more comprehensive and high-quality evaluation framework for assessing knowledge transfer interventions in agriculture. They have underscored the inadequacy of the current evaluation practices to support evidence-based policy-making, which is required by EU regulation for the CAP strategic plans (Regulation, Citation2021/2115). Specifically, the existing indicators are loosely defined and primarily focus on the output levels (EC, Citation2022). As a result, respondents recognized that the planning of the knowledge transfer activities heavily relies on the subjective beliefs of the policymakers due to the lack of objective resources for providing insight into the actual effects (Weiss, Citation1999). This issue was not only identified in the context of knowledge transfer but also in other areas of the CAP (Erjavec & Rac, Citation2023). However, respondents have emphasized that the knowledge transfer domain seems particularly marginalized.

The interviewees agreed that the proposed evaluation framework was relevant and that its results reflect the current situation relatively accurately, highlighting key shortcomings and enabling a better understanding of the policy impacts:

If I had been given these indicators beforehand to assess them according to my own judgment, I would have probably assessed them very similarly to the results. […] From this perspective, I can say that these indicators seem reliable to me. If I, who have been working with these people in this field for so long, have this feeling, and the indicators confirm it, then it means that the tool is useful and that you have hit the mark. [Interview 6, knowledge transfer expert]

The interview results also highlighted certain limitations in the proposed framework and provided potential suggestions for improvement. Additional indicators were proposed by the interviewees across all three indicator levels. At the output level, the interviewees recommended adding the number of specialized advisors for different knowledge transfer fields of interest, the ratio of advisors to farms based on the farm size and structure, and the regional distribution of the implemented knowledge transfer activities. At the results level, they suggested offering farmers the option to express their interests in the potential training topics. Finally, for the impact level, the indicators assessing farmers’ actual behaviour should be added, e.g. by monitoring farmers’ enrolment in various groups of the AEMs. In addition, they would add an assessment of several context-related indicators, e.g. the farm bird index and conservation status of habitat types.

When considering the suitability of the evaluation framework, adherence to legal foundations was considered (Lipicer et al., Citation2009), especially the requirements of the relevant EU regulations and guidelines (e.g. EU, 2017; Regulation, 2021/2115). The interviewees agreed that the proposal demonstrates adequacy and flexibility with these. Moreover, they recognized that it surpasses the reporting needs of the European Commission, which, in their opinion, are less exact and, as already pointed out, guidelines lack adequate indicators of the result and impact level. However, the adaptive nature of these seems to ensure the possibility of integrating data from the proposed framework into the reporting needs.

4.2.2. Feasibility

Despite the indicated need for a more comprehensive assessment of the impact of knowledge transfer intervention, the interviewees identified several factors that could hinder the feasibility of the proposed framework. Firstly, they raised the issue of the effective involvement of the farmers in data collection, which is a known challenge when using questionnaires as an evaluation tool (Coon et al., Citation2020). Some interviewees questioned the credibility of survey data, as farmers may tend to provide pleasing and positive responses. This concern is especially relevant when surveys are conducted by government institutions or advisory services (Mase et al., Citation2015) because respondents may worry about the anonymity of their responses. Interviewees also noted that farmers often face a heavy survey burden, which can discourage their participation or could result in superficial and quick answers due to time constraints or survey fatigue (Coon et al., Citation2020).

To address the data collection challenges, the interviewees put forward several suggestions. Clear communication with farmers is crucial because it might ensure they understand the purpose of the survey and recognize the importance of their participation. This is particularly important for environmental topics in rural contexts, as they are often assumed to be less relevant (Brook et al., Citation2003; Coon et al., Citation2020). When designing questionnaires, it is important to consider a suitable structure that farmers can easily comprehend (Quinn, Citation2010). Suggestions included providing farmers with valuable content, including feedback on the survey results or other non-monetary compensations, such as additional individual advice. Finally, it is essential for evaluators or survey administrators to address farmers’ potential concerns about anonymity by clearly communicating the data management procedures in line with the established principles of ethical research. Potential biases could be further reduced by employing external research institutions or evaluation agencies to administer data collection.

Data availability was recognized to be another hindering factor (Castaño et al., Citation2019). During our data collection for the pilot assessment of output indicators, we encountered a lack of consistent and systematic reporting, relying on information from previous monitoring and evaluation sources. When examining reports from different time frames, we found inconsistent indicator names and unclear and variable data presentation. These challenges were also confirmed through expert interviews. Furthermore, a similar situation was observed when evaluating the effects of CAP cross-compliance, where inconsistencies were apparent between ex-ante and ex-post evaluations due to the involvement of multiple actors with different criteria, methods, and interpretations during the evaluation process (Bozzini & Hunt, Citation2015). Therefore, it is essential to ensure consistent reporting following transparent evaluation criteria to enhance the credibility and effectiveness of future evaluations.

Weakly defined intervention logic can also significantly impact evaluations (Donaldson et al., Citation2019). The interviewees highlighted that in the Slovenian knowledge transfer system, the issue lies in the diverse interests of stakeholders and the limited availability of data and evaluations, which results in unclear or unspecified needs. Consequently, interventions targeted numerous and overly broad objectives (ECA, Citation2017) with weak connections to the intended outcomes, which is a significant hurdle when striving for a comprehensive evaluation design (Lovec et al., Citation2020).

Limited human resources can present another significant constraint (Cagliero et al., Citation2021; El Benni et al., Citation2023). In the context of the CAP, national managing authorities, usually ministries, are responsible for policy design and implementation. However, the implementation is entrusted to paying agencies, while private consulting groups or research institutions are typically responsible for the evaluations (Castaño et al., Citation2019). Based on the interviews, limited human resources manifest among those bodies on various levels and could hinder the implementation of a proposed evaluation framework. Firstly, only a few individuals are often engaged in the evaluation process (Erjavec & Rac, Citation2023). For example, in Slovenia, only one person is partially dedicated to planning evaluations at the authorized agriculture ministry. Moreover, there is a limited number of institutions involved in conducting evaluations. The issue is further emphasized by the limited coordination between those actors, which can also negatively impact the quality of evaluations (Castaño et al., Citation2019):

When we started conducting [name of the evaluation], it became evident that there was a lack of understanding of our role as evaluators. It felt like we were hitting a wall right from the beginning. We realised that people at the ministry had previously undergone an audit, so they treated us like auditors and provided minimal responses without putting in any effort to contribute to the success of the evaluation. […] Most of the time, they perceived evaluations as a mere obligation to meet the requirements of the European Commission. They were also somewhat defensive if the results did not meet their expectations. The atmosphere became very hostile, as if everything we proposed was wrong. [Interview 13, evaluator]

According to the interviewees, the proposed evaluation methodology is ambitious compared to current approach (Regulation, Citation2021/2115) and it enables the acquisition of data and insights crucial for real-time and evidence-based policy planning. This is essential for addressing current issues of formalistic and poorly designed intervention logic (Erjavec & Rac, Citation2023), particularly considering the European Commissions’ priority for data-driven and targeted strategic planning of CAP (ECA, Citation2017). However, interviewees expressed concerns about the practicality and systematic implementation of the methodology if applied extensively across multiple policy domains. They considered the methodology feasible for in-depth thematic evaluations of the specific policy domains.

This is the cost of evidence-based policy. The funding and resources are not a problem if we do it only in the field of knowledge transfer, but this is just one of the 35–40 topics. If all areas have to be evaluated similarly, the costs become a serious issue: financially, in terms of human resources, and in other aspects. But if you don't do it, then it's not evidence-based. Otherwise, you'll be throwing millions of euros out of the window and not knowing what you've achieved. [interview 8, researcher]

In Slovenia, these evaluations are often carried out solely because the EU demands and funds them. […] The [ministry] focuses on trying to transpose the EU's requirements precisely into Slovenian legislation. The main logic remains to obtain as much available funding as possible. However, they do not engage in the more challenging task of ensuring that the European policy framework can genuinely benefit Slovenia and develop its own path. [interview 10, researcher]

5. Conclusions

Our study aimed to construct a comprehensive evaluation framework to assess the effectiveness of knowledge transfer and innovation interventions in agriculture by using a theory-based approach. Specifically, our goal was to fill the gaps in the CAP monitoring and evaluation framework by creating indicators that could capture the broader impacts of interventions, including shifts in normative and behavioural aspects resulting from knowledge transfer initiatives. This objective is particularly significant considering the current priorities of the CAP, which emphasize the importance of better policy targeting and results orientation (Beck et al., Citation2021; ECA, Citation2017).

Our extended evaluation framework adhered to a three-level hierarchy of indicators to ensure alignment with the established common framework for monitoring and evaluating CAP's Rural Development Programmes (Regulation, Citation2021/2115). At the output indicator level, our study contributed to the existing framework by systematically categorizing indicators from the previous and current monitoring and evaluation systems. Moving to the result and impact levels of the indicators, we extended the existing system by introducing new indicators and appropriate survey instruments. These were built upon the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991) and supplemented with additional theoretical components to assess knowledge transfer activities. While the evaluation framework was explicitly adapted for agri-environmental themes, the skeleton of the evaluation framework is designed to be versatile and applicable across diverse knowledge transfer activities and interventions.

The application of the TPB as a part of the evaluation framework constitutes a novel approach in its utilization, especially in the domain of knowledge transfer in agriculture (Hall et al., Citation2019; Sok et al., Citation2021). Our study has demonstrated its applicability as a valuable tool within this realm, as it has allowed us to gain insightful perspectives on the effectiveness of knowledge transfer interventions, particularly in assessing the anticipated changes in the farmers’ values and their behaviour. Furthermore, by engaging farmers, i.e. beneficiaries of the interventions, into the evaluation process and the ensuing policy cycle represents an additional strength of the study (ECA, Citation2015). Active engagement of the beneficiaries may reframe the policy as less exogenous for farmers and can grant them a sense of ownership, thus empowering them to contribute to policy formulation. This is vital for the long-term strengthening of sustainability and effectiveness of agricultural policies (Luján Soto et al., Citation2021). Moreover, using this evaluation methodology also enables the expedited dissemination of such information. This is crucial because delayed and ad-hoc evaluations often hinder acquiring high-quality evaluation results and their timely integration into the policy planning process (Bozzini & Hunt, Citation2015; ECA, Citation2017).

While the proposed evaluation framework offers several benefits, its practical implementation can encounter distinctive challenges. A primary concern revolves around the necessity for unbiased, continuous, and prolonged data collection – a task susceptible to numerous challenges. Insights gained from interviews with the AKIS actors indicated that these might include ineffective recruitment of farmers, survey fatigue and a lack of sufficient financial and human resources for ensuring data collection over multiple CAP programming periods. Furthermore, the need to establish the prevalent evaluation culture among the stakeholders and the political commitment to evidence-based policy-making was emphasized, thus elevating evaluation from a mere resource justification tool to a means of knowledge generation, which can effectively uncover policy impacts and thus inform decision-making.

This study contributes to research on education and knowledge transfer policy interventions where longitudinal studies are needed to understand the sustained impacts and their potential to accelerate behavioural change over time. Furthermore, cross-national comparative analyses could provide insights into the effectiveness of these interventions within diverse cultural and policy contexts. Lastly, integrating qualitative methods could deepen our understanding of the underlying factors that shape farmers’ attitudes and behaviour (Prager et al., Citation2017). These avenues of research can enrich our comprehension of the intricate dynamics surrounding knowledge transfer and facilitate evidence-based policies and practices that bolster agricultural sustainability and innovation.

Novak_Appendix_fin.docx

Download MS Word (1.5 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2011). Behavior interventions: Design and evaluation guided by the theory of planned behavior. In M. M. Mark, S. I. Donaldson, & B. C. Campbell (Eds.), Social psychology and evaluation (pp. 74–101). Guilford Press.

- Alif, Ž, Novak, A., Mihelič, R., Juvančič, L., & Šumrada, T. (2024). Can knowledge transfer speed up climate change mitigation in agriculture? A randomized experimental evaluation of participatory workshops. Environmental Science & Policy, 152, 103662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2023.103662

- Beck, M., Van Bunnen, P., Wathelet, J.-M., Cozier, J., Ghysen, A., Micha, E., Kubinakova, K., & Mantino, F. (2021). Evaluation support study on the CAP’s impact on knowledge exchange and advisory activities: Final report. Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2762045268.

- Bedrač, M., Bele, S., Brečko, J., Hiti Dvoršak, A., Kožar, M., Ložar, L., Moljk, B., Telič, V., Travnikar, T., & Zagorc, B. (2023). Poročilo o stanju kmetijstva, živilstva, gozdarstva in ribištva 2022 [Report on the state of agriculture, food, forestry and fisheries in 2022]. Agricultural Institute of Slovenia; Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food of the Republic of Slovenia. https://www.kis.si/f/docs/Porocila_o_stanju_v_kmetijstvu/ZP_2022_splosno__priloge_2.pdf

- Bonan, J., & Pagani, L. (2018). Junior farmer field schools, agricultural knowledge and spillover effects: Quasi-experimental evidence from northern Uganda. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(11), 2007–2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1355457

- Bourne, M., Bruyn, L. L. d., & Prior, J. (2021). Participatory versus traditional agricultural advisory models for training farmers in conservation agriculture: A comparative analysis from Kenya. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 27(2), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2020.1828113

- Bozzini, E., & Hunt, J. (2015). Bringing evaluation into the policy cycle: CAP cross compliance and the defining and re–defining of objectives and indicators. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 6(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1867299X00004281

- Brook, A., Zint, M., & De Young, R. (2003). Landowners' responses to an endangered species act listing and implications for encouraging conservation. Conservation Biology, 17(6), 1638–1649. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00258.x

- Brown, C., Kovacs, E., Herzon, I., Villamayor-Tomas, S., Albizua, A., Galanaki, A., Grammatikopoulou, I., McCracken, D., Olsson, J., & Zinngrebe, Y. (2020). Simplistic understandings of farmer motivations could undermine the environmental potential of the common agricultural policy. Land Use Policy, 101, 105136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105136

- Cagliero, R., Legnini, M., & Licciardo, F. (2021). Evaluating the new common agricultural policy: Improving the rules. EuroChoices, 20(3), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692X.12315

- Cairney, P. (2019). Understanding public policy: Theories and issues (2nd). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Castaño, J., Blanco, M., & Martinez, P. (2019). Reviewing counterfactual analyses to assess impacts of EU rural development programmes: What lessons can be learned from the 2007–2013 ex-post evaluations? Sustainability, 11(4), 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041105

- Cawley, A., O'Donoghue, C., Heanue, K., Hilliard, R., & Sheehan, M. (2018). The impact of extension services on farm-level income: An instrumental variable approach to combat endogeneity concerns. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 40(4), 585–612. https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/ppx062

- Chen, H. (1990). Issues in constructing program theory. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1990(47), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1551

- Colquhoun, H. L., Lowe, D., Helis, E., Belanger, D., Ens, B., Hill, S., Mayhew, A., Taylor, M., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2016). Evaluation of a training program for medicines-oriented policymakers to use a database of systematic reviews. Health Research Policy and Systems, 14(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0140-1

- Coon, J. J., van Riper, C. J., Morton, L. W., & Miller, J. R. (2020). Evaluating nonresponse bias in survey research conducted in the rural midwest. Society & Natural Resources, 33(8), 968–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1705950

- Czajkowski, M., Zagórska, K., Letki, N., Tryjanowski, P., & Wąs, A. (2021). Drivers of farmers’ willingness to adopt extensive farming practices in a globally important bird area. Land Use Policy, 107, 104223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104223

- Dahler-Larsen, P., & Boodhoo, A. (2019). Evaluation culture and good governance: Is there a link? Evaluation, 25(3), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389018819110

- Danso-Abbeam, G. (2022). Do agricultural extension services promote adoption of soil and water conservation practices? Evidence from northern Ghana Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 10, 100381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100381

- Dinar, A., Karagiannis, G., & Tzouvelekas, V. (2007). Evaluating the impact of agricultural extension on farms’ performance in crete: A nonneutral stochastic frontier approach. Agricultural Economics, 36(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2007.00193.x

- Donaldson, S I. (2007). Program theory-driven evaluation science: Strategies and application. Routledge.

- Donaldson, S. I., Lee, J. Y., & Donaldson, S. I. (2019). The effectiveness of positive psychology interventions in the workplace: A theory-driven evaluation approach. In L. E. Van Zyl & S. Rothmann Sr. (Eds.), Theoretical approaches to multi-cultural positive psychological interventions (pp. 115–159). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20583-6_6.

- EC. (2017). Technical handbook monitoring evaluation framework of the Common agricultural policy 2014–2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/food-farming-fisheries/key_policies/documents/technical-handbook-monitoring-evaluation-framework_june17_en.pdf

- EC. (2022). Evaluation of the CAP's impact on knowledge exchange and advisory activities (p. 74). European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-register/detail?ref=SWD(2022)137&lang=sl

- ECA. (2015). Special Report No 12/2015: The EU priority of promoting a knowledge-based rural economy has been affected by poor management of knowledge-transfer and advisory measures. European Court of Auditors. http://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/Report.aspx?did=33224&TermStoreId=8935807f-8495-4a93-a302-f4b76776d8ea&TermSetId=49e662c4-f172-43ae-8a5e-7276133de92c&TermId=5f6589a2-5a2e-4ae8-8cc6-e05bf544b71f

- ECA. (2017). Rural development programming: Less complexity and more focus on results needed. Special report No 16, 2017. European Court of Auditors. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2865357364

- El Benni, N., Grovermann, C., & Finger, R. (2023). Towards more evidence-based agricultural and food policies. Q Open, 3, qoad003. https://doi.org/10.1093/qopen/qoad003

- ENRD. (2016). Rural Development Priority 1: Knowledge transfer and innovation in agriculture, forestry and rural areas. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/priority-1-summary.pdf

- ENRD. (2019). RDP analysis: Support to environment & climate change—M01 & M02: Knowledge transfer & Advisory services. European Network for Rural Development. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/rdp_analysis_m01-02.pdf

- Erjavec, E., & Rac, I. (2023). Improving the quality of CAP strategic planning through enhancing the role of agricultural economics. EuroChoices, 22, 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692X.12393

- Erjavec, E., Šumrada, T., Juvančič, L., Rac, I., Cunder, T., Bedrač, M., Lovec, M., Bučar, M., & Volk, T. (2018). Vrednotenje slovenske kmetijske politike v obdobju 2015-2020: Raziskovalna podpora za strateško načrtovanje po letu 2020. Kmetijski inštitut Slovenije. https://www.program-podezelja.si/sl/knjiznica/287-vrednotenje-slovenske-kmetijske-politike-v-obdobju-2015-2020/file.

- Faure, G., Desjeux, Y., & Gasselin, P. (2012). New challenges in agricultural advisory services from a research perspective: A literature review, synthesis and research agenda. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 18(5), 461–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2012.707063

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Taylor and Francis.

- Fitzpatrick, J. L., Sanders, J. R., & Worthen, B. R. (2011). Program evaluation: Alternative approaches and practical guidelines. Pearson Education.

- Gaffey, V. (2013). A fresh look at the intervention logic of structural funds. Evaluation, 19(2), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389013485196

- Giulivi, N., Harou, A. P., Gautam, S., & Guereña, D. (2023). Getting the message out: Information and communication technologies and agricultural extension. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 105(3), 1011–1045. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12348

- Gopal, R., Singh, V., & Aggarwal, A. (2021). Impact of online classes on the satisfaction and performance of students during the pandemic period of COVID 19. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 6923–6947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10523-1

- Grinnell, R. M., Gabor, P., & Unrau, Y. A. (2016). Program evaluation for social workers: Foundations of evidence-based programs. Oxford University Press.

- Hall, A., Turner, L., & Kilpatrick, S. (2019). Using the theory of planned behaviour framework to understand Tasmanian dairy farmer engagement with extension activities to inform future delivery. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 25(3), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2019.1571422

- Harmelink, M., Nilsson, L., & Harmsen, R. (2008). Theory-based policy evaluation of 20 energy efficiency instruments. Energy Efficiency, 1(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-008-9007-9

- Hill, B., Bradley, D., & Williams, E. (2017). Evaluation of knowledge transfer; conceptual and practical problems of impact assessment of farming connect in Wales. Journal of Rural Studies, 49, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.11.003

- Hollett, R. C., Gignac, G. E., Milligan, S., & Chang, P. (2020). Explaining lecture attendance behavior via structural equation modeling: Self-determination theory and the theory of planned behavior. Learning and Individual Differences, 81, 101907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101907

- Ingram, J., Mills, J., Black, J., Chivers, C.-A., & Skaalsveen, K. (2022). Do agricultural advisory services in Europe have the capacity to support the transition to healthy soils? Land, 11(5), 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11050599

- JSKS. (2021). Zbirnik letnega poročila o delu Javne službe kmetijskega svetovanja za leto 2020.

- JSKS. (2023). Kmetijsko svetovanje [Agricultural advisory]. Javna služba kmetijskega svetovanja. https://www.kgzs.si/jsks.

- KGZS. (2021). Zbirnik letnega poročila o delu Javne službe kmetijskega svetovanja za leto 2020 (Report). Kmetijsko gospodarska zbornica Slovenije.

- Knierim, A., Labarthe, P., Laurent, C., Prager, K., Kania, J., Madureira, L., & Ndah, T. H. (2017). Pluralism of agricultural advisory service providers – Facts and insights from Europe. Journal of Rural Studies, 55, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.07.018

- Knook, J., & Turner, J. A. (2020). Reshaping a farming culture through participatory extension: An institutional logics perspective. Journal of Rural Studies, 78, 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.037

- Kreft, C., Angst, M., Huber, R., & Finger, R. (2023). Farmers’ social networks and regional spillover effects in agricultural climate change mitigation. Climatic Change, 176(2), 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03484-6

- Lioutas, E. D., Charatsari, C., Istenič, MČ, Rocca, G. L., & Rosa, M. D. (2019). The challenges of setting up the evaluation of extension systems by using a systems approach: The case of Greece, Italy and Slovenia. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 25(2), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2019.1583818

- Lipicer, S. K., Fink-Hafner, D., Kropivnik, S., & Židan, A. (2009). Vrednotenje javnih politik. Fakulteta za družbene vede.

- Lovec, M., Šumrada, T., & Erjavec, E. (2020). New CAP delivery model, old issues. Intereconomics, 55(2), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-020-0880-6

- Luján Soto, R., de Vente, J., & Cuéllar Padilla, M. (2021). Learning from farmers’ experiences with participatory monitoring and evaluation of regenerative agriculture based on visual soil assessment. Journal of Rural Studies, 88, 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.10.017

- Mase, A. S., Babin, N. L., Prokopy, L. S., & Genskow, K. D. (2015). Trust in sources of soil and water quality information: Implications for environmental outreach and education. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 51(6), 1656–1666. https://doi.org/10.1111/1752-1688.12349

- Masset, E., & Haddad, L. (2015). Does beneficiary farmer feedback improve project performance? An impact study of a participatory monitoring intervention in Mindanao, Philippines. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(3), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.959933

- Mayne, J. (2009). Building an evaluative culture: The key to effective evaluation and results management. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 24(2), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.24.001

- MKGP. (2021). Letno poročilo o izvajanju Program razvoja podeželja RS za obdobje 2014-2020 za leto 2020. Ministrstvo za kmetijstvo, gozdarstvi in prehrano, Republika Slovenija. https://skp.si/prp-2014-2020-2022/spremljanje-in-vrednotenje-2014-2020/spremljanje-prp.

- Nordin, M., & Höjgård, S. (2017). An evaluation of extension services in Sweden. Agricultural Economics, 48(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12294

- Novak, A., Šumrada, T., Istenič, MČ, & Erjavec, E. (2022). Farmers’ decision to participate in agri-environmental measures for the conservation of extensive grasslands in the Haloze region. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica, 118(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.14720/aas.2022.118.1.2011

- OECD. (2015). Fostering Green Growth in Agriculture: The Role of Training, Advisory Services and Extension Initiatives | READ online. Oecd-Ilibrary.Org. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/agriculture-and-food/fostering-green-growth-in-agriculture_9789264232198-en.

- Oyinbo, O., Chamberlin, J., Vanlauwe, B., Vranken, L., Kamara, Y. A., Craufurd, P., & Maertens, M. (2019). Farmers' preferences for high-input agriculture supported by site-specific extension services: Evidence from a choice experiment in Nigeria. Agricultural Systems, 173, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.02.003

- Paschen, J.-A., Reichelt, N., King, B., Ayre, M., & Nettle, R. (2017). Enrolling advisers in governing privatised agricultural extension in Australia: Challenges and opportunities for the research, development and extension system. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 23(3), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2017.1320642

- Petit, M. (2019). Another reform of the common agricultural policy: What to expect. EuroChoices, 18(1), 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692X.12221

- Prager, K., Creaney, R., & Lorenzo-Arribas, A. (2017). Criteria for a system level evaluation of farm advisory services. Land Use Policy, 61, 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.11.003

- Quinn, K. (2010). Methodological considerations in surveys of older adults: Technology matters. International Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society, 8, 114–133. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.3897.9209

- Rajalahti, R., & Swanson, B. (2010). Strengthening agricultural extension and advisory systems: Procedures for assessing, transforming, and evaluating extension systems. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Strengthening-agricultural-extension-and-advisory-%3A-Rajalahti-Swanson/a4b34c47ebf0ae2248f94420b66e2c1ed7b65db0.

- Regulation 2021/2115. (2021). http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/2115/oj

- Regulation 834/2014. (2014). http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2014/834/oj

- Rezaei, R., Safa, L., Damalas, C. A., & Ganjkhanloo, M. M. (2019). Drivers of farmers' intention to use integrated pest management: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. Journal of Environmental Management, 236, 328–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.01.097

- Saldana, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE.

- Skoglund, E., Fernandez, J., Sherer, J. T., Coyle, E. A., Garey, K. W., Fleming, M. L., & Sofjan, A. K. (2020). Using the theory of planned behavior to evaluate factors that influence PharmD students’ intention to attend lectures. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(5), 7550. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7550

- Sok, J., Borges, J. R., Schmidt, P., & Ajzen, I. (2021). Farmer behaviour as reasoned action: A critical review of research with the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 72(2), 388–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12408

- Stupak, N., Sanders, J., & Heinrich, B. (2019). The role of farmers' understanding of nature in shaping their uptake of nature protection measures. Ecological Economics, 157, 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.11.022

- Šumrada, T., Japelj, A., Verbič, M., & Erjavec, E. (2022). Farmers’ preferences for result-based schemes for grassland conservation in Slovenia. Journal for Nature Conservation, 66, 126143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2022.126143

- Šumrada, T., Lovec, M., Juvančič, L., Rac, I., & Erjavec, E. (2020). Fit for the task? Integration of biodiversity policy into the post-2020 common agricultural policy: Illustration on the case of Slovenia. Journal for Nature Conservation, 54, 125804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2020.125804

- SURS. (2020). Agricultural census 2020: Labour force on agricultural holdings. Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStat/en/Podrocja/Index/85/agriculture-forestry-and-fishery.

- Tama, R. A. Z., Ying, L., Yu, M., Hoque, M. M., Adnan, K. M., & Sarker, S. A. (2021). Assessing farmers’ intention towards conservation agriculture by using the extended theory of planned behavior. Journal of Environmental Management, 280, 111654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111654

- Thomas, E., Riley, M., & Spees, J. (2020). Knowledge flows: Farmers’ social relations and knowledge sharing practices in ‘catchment sensitive farming’. Land Use Policy, 90, 104254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104254

- Van Belle, S. B., Marchal, B., Dubourg, D., & Kegels, G. (2010). How to develop a theory-driven evaluation design? Lessons learned from an adolescent sexual and reproductive health programme in West Africa. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 741. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-741

- Wang, S. L. (2014). Cooperative extension system: Trends and economic impacts on U.S. Agriculture. Choices: The Magazine of Food, Farm, and Resource, 29.

- Wąs, A., Malak-Rawlikowska, A., Zavalloni, M., Viaggi, D., Kobus, P., & Sulewski, P. (2021). In search of factors determining the participation of farmers in agri-environmental schemes – Does only money matter in Poland? Land Use Policy, 101, 105190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105190

- Wauters, E., Bielders, C., Poesen, J., Govers, G., & Mathijs, E. (2010). Adoption of soil conservation practices in Belgium: An examination of the theory of planned behaviour in the agri-environmental domain. Land Use Policy, 27(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.02.009

- Weiss, C. H. (1997). Theory-based evaluation: Past, present, and future. New Directions for Evaluation, 1997(76), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1086

- Weiss, C. H. (1999). The interface between evaluation and public policy. Evaluation, 5(4), 468–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/135638909900500408

- Włodarczyk-Marciniak, R., Frankiewicz, P., & Krauze, K. (2020). Socio-cultural valuation of Polish agricultural landscape components by farmers and its consequences. Journal of Rural Studies, 74, 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.01.017