?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Urban agriculture (UA) empowers women by providing economic opportunities, control over food, social connections, new skills, and improved health. Despite its importance, Ethiopian women's participation in UA remains low. This study aimed to examine the factors that influencing women's motivation to participate in UA in Hossana town, Ethiopia. We analysed survey data from 272 women participating in UA using a multivariate probit model. We identified four primary motivational dimensions: food security, economic reasons, social connection, and general well-being. The results revealed that combination of food security and economic motivations were the main drivers for women to participate in UA. The multivariate probit model results showed that age, education level, marital status, family size, employment status, non-urban farm income, farm experience, garden size, access to credit and markets, and the use of improved inputs all significantly influence the likelihood of women’s motivations to participate in UA. These findings provide valuable insights into the motivating factors driving women’s participation in UA and suggest the potential bundling of motivations. They lay the groundwork for more effective policies and programmes to support women's participation in this crucial sector of UA.

1. Introduction

Ethiopia's rural agricultural land remains incredibly important, but the country is facing challenges with rapid urbanization (5.4% per year, one of the highest in the world), an increasing urban population, and the rising prices of food and living costs (UN, Citation2019; Yalew, Citation2020). Furthermore, the country’s food insecurity ranks among the worst globally, with the World Food Programme (WFP) ranking it as the third most affected country (FSIN, Citation2022). The ongoing conflicts in certain regions further worsen the issue, as they hinder movement and agricultural production, resulting in a decline in nutrition and food security across the entire nation (Muriuki et al., Citation2023). In this situation, urban agriculture (UA) emerges as a crucial solution to address food security concerns and improve urban livelihoods, contributing to the creation of sustainable and resilient cities (Gebremedhin et al., Citation2023; Olivier, Citation2019). The escalating costs of transporting food from rural to urban areas have created obstacles for urban residents to access fresh and nutritious food. Urban agriculture, however, provides a local remedy by reducing dependence on distant food supply chains and promoting dietary diversity (Badami & Ramankutty, Citation2015; Delelegn & Mulugeta, Citation2018).

Recognizing the benefits, the Ethiopian government actively promotes urban agriculture through initiatives such as Farm Africa’s projects, aligning with the broader goals of the Green Legacy to enhance sustainable urban agriculture and environmental well-being (EM, Citation2023; Lambert & Orkaido, Citation2023). In urban areas like Addis Ababa, where a substantial population grapples with poverty, they face daily hurdles in purchasing nutritious food due to high inflation rates and the cost of living at various levels today (Nega, Citation2023). Urban agriculture stands as a promising solution to address food insecurity in these urban areas by improving household food supply through the physical availability of food, generating income, and fostering savings in diverse socioeconomic contexts (Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019; Mok et al., Citation2014). Apart from its roles in food security, UA serves as a multifaceted activity enhancing health, well-being, social cohesion, economic opportunities, education, and the environment for city dwellers (Audate et al., Citation2021; Diekmann et al., Citation2020; Kirby et al., Citation2021). Urban agriculture is defined as ‘small areas (e.g. vacant plots, gardens, verges, balconies, and containers) within the city for growing crops and raising small livestock or milk cows for own consumption or sale in neighbourhood markets’ that can provide a source of food and income for urban dwellers (FAO & Rikolto, Citation2022). One noteworthy project is Farm Africa's urban agriculture pilot initiative in Addis Ababa, which has demonstrated the positive impact of cultivating food in cities. It has empowered low-income urban communities, especially women, to grow their own produce and keep chickens and fish (Nega, Citation2023).

Women’s active participation in agriculture is crucial for economic development and ensuring food security globally. They comprise about 43% of the agricultural labour force, both globally and in developing countries (Raney et al., Citation2011). In Ethiopia, women play a crucial role in agricultural production, contributing significantly between 40 and 60% to the labour force (Abebe & Yazie, Citation2019). Urban agriculture offers various benefits that are particularly important for encouraging socio-economically disadvantaged women to adopt new dietary practices and contribute to their households’ well-being (Martin et al., Citation2017). It also empowers women by giving them control over their food production, connecting them with their communities, and helping them learn new skills (FAO, Citation2023; Hadebe & Mpofu, Citation2013). Despite these advantages, women's participation in urban agriculture in Ethiopia remains low, and it has received little attention. According to the Central Statistical Agency (2014), only 13% of urban agriculture participants in Ethiopia are women. Understanding women's motivations for engaging in urban agriculture is essential to identifying gender-related barriers and promoting inclusivity in urban agriculture development.

The motivations of urban agriculture participants are complex and multifaceted (Diekmann et al., Citation2020; Kirby et al., Citation2021). Several studies have explored the different motivations of UA practitioners. For instance, Audate et al. (Citation2021) highlighted key motivations such as self-provision of healthy food, health and wellbeing, empowerment, social capital, and economic rewards. Another study by Cattivelli (Citation2023) revealed that urban gardening during the pandemic waves provided personal and community wellbeing, food supply security, and the opportunity to spend time having fun outside the home. Pollard et al. (Citation2018) differentiated between motives for home gardeners and community gardeners, emphasizing factors like growing food, happiness, well-being, and social connections. Poulsen et al. (Citation2015) also found that subsistence and financial benefit are primary reasons to participate in low-income UA countries.

While some women engage in UA to meet daily household support, others see it as a path to achieving social and economic empowerment (Hovorka, Citation2006). However, there is a lack of literature that specifically examines the motivations of women involved in UA, particularly in the Ethiopian context. Studies conducted in Nigeria suggest that women participate in urban agriculture for food security, income supplementation, and land accessibility (Adebisi & Monisola, Citation2012). Researchers in Sri Lanka, Gamhewage et al. (Citation2015), explored women's participation in UA and its impact on family economies, while in Indonesia, Safitri et al. (Citation2021) assessed urban farming as a means of women's empowerment. Another study, McNicoll (Citation2011), focused on mainstreaming gender in UA and food security, highlighting women’s roles in feeding cities. However, these studies only address one or a few reasons why women engage in UA. Likewise, in Ethiopia, there is a dearth of research on the topic.

To bridge this gap, it's crucial to conduct research that delves into the complex relationships between women's motivations and the factors influencing these motivations in Ethiopian urban agriculture. This study aims to answer three critical research questions: (1) In the study area, what are the socio-economic characteristics of women engaged in urban agriculture? (2) What motivates women to participate in urban agriculture? (3) What factors influence the motivations for women's participation in urban agriculture? Therefore, using a multivariate probit model, the objective of this study is to examine the motivations for women's participation in UA and the socioeconomic factors influencing these motivations in Hossana town, Ethiopia. The research findings will assist policymakers, local authorities, and development organizations in formulating targeted strategies to promote women's engagement and empowerment in urban agriculture and sustainable practices. Additionally, it will contribute to the broader literature on sustainable agriculture, gender equality, and urban development.

2. Methodology

2.1. Description of the study area

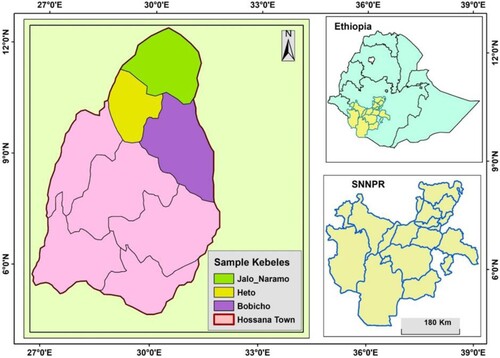

Hossana town is part of Ethiopia’s Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Region (SNNPR). The town lies 232 km south of Addis Ababa, the national capital, and 194 km west of Hawassa, the regional city. Functioning as the administrative centre of the Hadiya Zone, Hossana town (see ) is geographically located at a latitude of 7°33′N and a longitude of 37°51′E, with an elevation of 2177 metres above sea level. The town experiences a bimodal rainfall pattern, characterized by a long rainy season from June to September and a short rainy season from mid-February to late April. Highland regions classify these climatic conditions as ‘Weynadega’.

Hossana town is divided into eight urban kebeles: Bobicho, Jalo-naramo, Heto, Lich-amba, Meel-amba, Lebasha, Arada, and Betel. The town’s population is approximately 97,184 residents, with slightly more females (50.8%) compared to males (49.2%). The annual average population growth rate in Hossana is relatively high at 10.4%, with an estimated density of 2484 people per square kilometre (CSA, Citation2014). Urban farming practices in Hossana town primarily revolve around dairy, poultry, and vegetable production. These activities play a pivotal role in ensuring household food security and income for the residents of Hossana (HTFAED, Citation2014).

2.2. Data types, sources, and methods of data collection

This study used cross-sectional survey data collected from selected areas of Hossana town between June and July 2023. To collect the necessary information, the study used primary sources of data. We collected the primary data through a combination of surveys and structured interviews with women participating in UA in the study area. Survey questionnaires gathered quantitative information on UA practices, socio-economic factors, and institutional factors that influence women’s motivations to participate in UA. Structured interviews provided qualitative insights, utilizing predetermined questions based on existing literature to capture a diverse range of motivations. Participants in the interviews were given a list of predetermined motivations derived from the literature, allowing them to choose and elaborate on their reasons for engaging in UA. These predetermined motivations were organized into four distinct groups based on common characteristics, as outlined in . This categorization aimed to streamline the analysis and highlight patterns in women's motivations for UA. A team of trained enumerators and researchers administered questionnaires and conducted the interviews.

2.3. Sampling techniques and sample size

Hossana town, like most urban areas, has various levels of UA practice. These activities typically take place in private backyards, front yards, rented houses, and vacant municipal spaces. Due to the town’s limited vacant spaces, fewer people participate in UA at community gardens. As a result, the study's target population consisted of women in Hossana town practicing UA to any level in their individual backyards, front yards, and rented houses. These women may be primary or secondary workers, part of farm households or not, and engage in a variety of endeavours, from side jobs to full-time enterprises. This study employed a multi-stage sampling technique. At first, we purposely selected Hossana town, the capital and most populous town in the Hadiya zone, for its suitability in studying urban agricultural practices. In the second stage, three kebeles, namely Bobicho, Jalo-naramo, and Heto, were chosen purposively from the eight kebeles in the town due to their relative potential in urban agriculture practice compared to the others. To determine the sample size, the researcher obtained the estimated number of women engaged in UA from the town’s urban agricultural office. Finally, purposive and snowball sampling techniques were applied to select a sample of 272 women engaged in UA from each sample kebeles ().

The sample was determined using Yamane (Citation1967) formula and is as follows:

Where:

= required sample size; N = total population size (855) and e = desired level of precision (0.05).

Table 1. Distribution of sample women for each kebele.

2.4. Method of data analysis

We used both descriptive and econometric models to achieve the specific research objectives. We employed descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and percentages, to describe the characteristics of the sampled respondents and the prevalent motivations among women participating in urban agriculture.

2.4.1. Econometric analysis of women’s motivations for participation in urban agriculture: a multivariate probit approach

This study employs a multivariate probit (MVP) regression model to examine the factors influencing women's motivations for participating in urban agriculture (UA). The MVP regression model, an extension of the probit model, allows for the simultaneous estimation of multiple binary dependent variables (Greene, Citation2012). The study used four potential motivation categories for women's participation in UA: food security (ensuring access to fresh and nutritious food), economic reasons (earning income through selling produce), social connections (building relationships with other community members), and general well-being (improving mental and physical health through gardening). The empirical specification of choice decisions over the four categories of motivations for participating in UA can be modelled in two ways: by either multinomial or multivariate regression analysis. One of the underlying assumptions of the multinomial model is the independence of irrelevant alternatives; that is, the error terms of the choice equations are mutually exclusive (Greene, Citation2012). However, the motivations driving women's participation in urban agriculture are not mutually exclusive; women are more likely to simultaneously choose a combination of motivations, potentially leading to a correlation between the random error components of the motivation category. Therefore, we propose employing an MVP model that allows for the simultaneous analysis of multiple motivations, taking into account possible correlations between them. The MVP method considers the effect of explanatory variables on each motivational dimension, as well as potential unobserved connections between disturbances (Green, Citation2002). However, it is important to note that the complexity of the MVP model may pose challenges in estimation, especially as the number of choice units increases (Cappellari & Jenkins, Citation2003).

2.4.1.1. Conceptual framework

The study conceptualizes women's motivations for participation in UA using a random utility function, providing a robust framework to understand the diverse determinants influencing their choices.

The women's motivations for participation in urban agriculture can be conceptualized using a random utility function, providing a robust framework for understanding the multifaceted determinants that influence their choices. In this context, the utility function captures the latent satisfaction or benefit that the woman derives from her decision to participate in urban agriculture, taking into account both observable and unobservable factors. The utility function for the

woman

can be expressed as

(1)

(1) Here

represents the latent utility for the

woman,

is a vector of observable factors influencing motivations (such as demographic and socioeconomic characteristics),

is a vector of coefficients corresponding to the independent variables, and

is the error term encompassing unobservable factors.

Now, the multivariate probit model assumes that the observed outcomes for the dependent variables (dimension of motivations: Food security (Y1), Economic reasons (Y2), Social connection (Y3), and General well-being (Y4)) are related to the latent utility through a set of threshold parameters. The specific model is expressed as

(2)

(2) Where,

represents women (

= 1,2, … N),

(j = 1, … 4) represents the four dimensions of motivations chosen by the

women,

is the observed variables that affects motivations,

is the unknown parameters (

), and

is the error term. A woman chooses the dimension that maximizes her latent utility, adjusted by the error term. If the latent utility is greater than

, then the individual

chooses the alternative

, and the dependent variable

becomes 1. Otherwise, the individual

does not select the alternative j, and the dependent variable becomes 0. Therefore, we define the choice function as follows:

(3)

(3) Where,

is latent variable, and

is threshold parameter specific to each category.

The hypothesis can be tested by running four different independent binary probit models and assuming that error terms are mutually exclusive. However, a correlation may exist between the motivations driving women to participate in UA, potentially leading stochastic dependence among the element of the error terms. In our multivariate probit framework, the error terms jointly follow a multivariate normal distribution (MVN) with mean zero and variance normalized to unity, = (y1,y2,y3,y4)

. The symmetric variance-covariance matrix

is specified as follows:

(4)

(4)

is the pairwise correlation coefficient of the error terms with respect to any two of the estimated motivation equations in the model. The off-diagonal elements of the variance-covariance matrix reveal the unobserved correlation among the stochastic components of various aspects of women’s motivation to participate in UA. Since the variance–covariance matrix

contains a correlation that may exist between unobserved effects and explanatory variables,

has a flexible structure, which is appropriate to analyse substitution and complement patterns among motivations. In this study, we estimate the parameters using simulated maximum likelihood estimation using STATA-14 software.

2.4.2. Description of variables

2.4.2.1. Dependent variables: motivations of women’s participation in UA

The study aims to examine factors influencing women’s motivations for participation in UA. We asked women to choose the most compelling reasons for their participation in UA. In the field survey, women identified various reasons for participating in UA. For the purpose of analysis, these reasons were grouped into four categories: food security, economic reasons, social connections, and general well-being based on common characteristics (). These reasons are similar to those looked at in previous research about people who take part in UA. These include food security, economic interests, physical and mental health outcomes, social capital, nutritional health impacts, and financial benefit (Cattivelli, Citation2023; Diekmann et al., Citation2020; Kirby et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Poulsen et al., Citation2015; Scheromm, Citation2015). Furthermore, women’s motivations to participate in UA are also influenced by several factors, such as demographic characteristics, economic conditions, institutional support, and the types of urban agriculture practices they are involved in (Audate et al., Citation2021; Kirby et al., Citation2020). The dependent and explanatory variables descriptions and expected signs are summarized as follows in .

Table 2. Grouped dimensions of women's motivations in urban agriculture.

Table 3. Description of variables used in the multivariate probit model.

3. Result and discussion

3.1. Descriptive statistic result

The descriptive statistics results provide a comprehensive overview of women's socio-demographic characteristics, institutional factors, types of urban agriculture practice, and the multiple motivations for practicing urban agriculture.

shows summary statistics of categorical variables for women practicing UA in Hossana Town. A large number (36%) were aged more than 50, 31.25% ranged from 31-50 years, and 32.72% were between 18 to 30 years. This suggests that older women represent a larger proportion (36%) of UA than other age groups. In terms of education levels, 20.22% were illiterate, 38.24% had completed primary education, and 19.12% had secondary education and high school, and 22.43% had pursued college or higher education. This indicates the majority of women UA participants in the study area held primary education. Regarding marital status, the result indicated that the majority of women 68.38% were married, while the remaining 31.62% were single. This suggests that engaging in UA requires stable residency and access to land and resources, giving married women an advantage as they are more likely to own homes and have access to land compared to single women. Furthermore, their active role in familial responsibilities and their desire to provide nutritious food options to their families may contribute to the higher engagement of married women in the UA. In terms of employment status, approximately 62.87% of women were housewives, while the remaining respondents were formal workers. This indicates the potential role of urban agriculture in empowering and enabling women to contribute to their family's food security and financial well-being. For housewives, urban agriculture can provide choice, purpose, and a renewed sense of empowerment, thereby increasing their drive to engage in these activities (FAO & Rikolto, Citation2022; Siegner et al., Citation2018). Of the total respondents, a significant proportion of women (78.31%) reported a lack of access to credit, while the remaining 21.69% had access to credit. Moreover, 51.10% of women did not have access to improved inputs, whereas the remaining 48.9% benefited from their use. A significant portion (54.41%) of women did not have access to the market, whereas 45.59% did. The most common urban agricultural practice among women in the study area was growing vegetables and fruits (56.99%), such as lettuce, cucumbers, pepper, basil, tomato, lemon and, etc. This is likely due to the brief production cycle of these crops. Subsequently, livestock farming accounted for 20.59% of the practices, whereas poultry farming and mixed farming represented 11.40% and 11.03%, respectively. Poultry, livestock, and mixed farming are more capital-intensive and costly, though they can provide significant income for women.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for categorical variables.

The sampled women had family sizes ranging from 2 to 9 members, with an average family size of 5.13 (). We found that women with larger family sizes were more likely to engage in urban agriculture, likely due to their motivation to provide sustenance and contribute financially. Regarding the economic context, the average monthly non-urban farm income of the women in the study was 1250 birr (22.5dollar). This implies that socioeconomically disadvantaged women were more likely to participate in urban agriculture to attain heightened economic empowerment. Furthermore, women who were motivated to participate in UA had an average of 8.59 years of farming experience, indicating that prior farming knowledge played a role in their decision to engage in urban agriculture for various motivations. The survey found that women’s garden sizes ranged from 20 to 90, with a mean of 56.6 square metres. This variation in urban land holdings shows how larger land allocations enable a broader range of gardening and farming activities, resulting in diversified agricultural practices that go beyond the scope of a single motivation.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics for continuous variable.

3.2. Motivations of women engaged in urban agriculture

displays the distribution of motivations among women participating in urban agriculture (UA) based on various dimensions: food security, economic reasons, social connection, and general well-being. Multiple motivations drive most women to participate in UA. Notably, the most common combination motivations were food security and economic reasons (17.3%), and economic reasons and social connections (13.2%). Interestingly, all four dimensions motivated 16.5% of women, while 11% practiced UA for a single motivation. Social connections and general well-being were not primary motivators. With a significant proportion (44.1%) of women engaging in UA due to three or more motivations, this aligns with the findings of (Audate et al., Citation2021). Their research indicates that motivations for UA participation encompass self-provision of healthy food, improved health and well-being, empowerment, social capital, and economic rewards.

Table 6. The proportion of women with multiple combinations of motivations to participate in UA.

These findings highlight the diverse range of reasons why women participate in UA, with the most prevalent motivations being food security and economic reasons. The results emphasize a shared understanding among women of the importance of cultivating their own food to ensure access to nutritious and affordable produce for their households. This aligns with a study by Khalil and Al Najar (Citation2021), which found that women commonly engage in UA to secure household food supplies and generate income. Moreover, the results indicate that generating income through selling surplus produce is a substantial motivation, supporting the study by Poulsen et al. (Citation2015) that identified subsistence and financial benefits as the primary motivations. The importance of UA goes beyond individual households, as it enables women to contribute to household food availability while balancing other responsibilities. This offers distinct benefits in terms of economic and social advancement. However, while this study did not find social connections and overall well-being as primary motivations, Kirby et al. (Citation2021) reported contrasting results, highlighting the importance of socialization in farming in Europe and the US. Similarly, studies by Othman et al. (Citation2019) and Diekmann et al. (Citation2020) emphasized the role of urban gardens in promoting social networks, physical and mental health, and social interactions with neighbours. This is because the motivations for UA vary between low- and middle-income countries (Lee et al., Citation2023). Therefore, these contextual differences underscore the need for localized interventions and highlight the varying motivations for UA across regions. Overall, the results contribute to the discourse on sustainable and inclusive urban food systems, emphasizing the role of women in ensuring access to nutritious and affordable produce.

3.3. Factors affecting motivations of women’s participation in urban agriculture: results of the multivariate probit model (MVP)

The results of the MVP model presented in provide valuable insights. First, the likelihood ratio test ( (6) = 71.516; Prob >

= 0.0000) rejects the null hypothesis that the error terms’ covariance across the equations is not correlated. This indicates that the pair-wise correlation coefficients across the error terms of the multiple choice equations are indeed correlated. Second, the fact that the null hypothesis that all regression coefficients in each equation are equal to zero was rejected (Wald chi2 (36) = 269.37; Prob > chi2 = 0.000) shows that the MVP model fits the data well. These statistics justify our decision to use MVP model to analyse women’s motivations for participation in UA.

Table 7. Correlation coefficients between motivations of women participation in UA.

3.3.1. Correlation among motivations of participation in urban agriculture

The pair-wise correlation coefficients across the residuals of the MVP model indicate that the four motivations women want to participate in UA are interdependent (). Positive correlation coefficients suggest that a woman’s motivation in one dimension of UA is likely to influence her choice of another associated dimension, implying a complementary relationship between these motivations. While negative signs indicate substitutability. The results show significant and positive associations between the following: economic reasons and food security; general well-being and food security; social connections and economic reasons; general well-being and social connections. This suggests that women tend to choose to participate in UA for these combined motivations, confirming the substantial benefits of these motivations. For example, the positive correlation between economic reasons and food security aligns with existing research by Poulsen et al. (Citation2015) indicating that engagement in UA can lead to both economic benefits and improved food security. Similarly, motivations related to reducing household expenditure and ensuring a fresh food supply, as identified by Church et al. (Citation2015) and Hamilton et al. (Citation2014), were positively correlated with women participating in UA for economic reasons and food security. These findings highlight that women tend to engage in UA for interconnected reasons, emphasizing the benefits of these motivations when combined.

Furthermore, the pair-wise correlation results indicate a significant and negative interdependence between well-being and economic reasons motivations. This suggests that in UA, women who prioritize general well-being may not primarily seek economic gains. Instead, their engagement may be more rooted in personal satisfaction and connection with nature. This finding aligns with the idea that some individuals view urban agriculture as a means of enhancing personal well-being and maintaining a connection with the environment rather than as a source of monetary benefits (Kirby et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, the positive correlation between general well-being and social connections suggests that women who prioritize their overall well-being are more likely to seek social connections through their engagement in UA. This aligns with the understanding that UA can serve as a platform for social interaction and community building, contributing positively to participants’ well-being (Grebitus et al., Citation2020; Tapia et al., Citation2021; Zhou et al., Citation2022). However, the insignificant positive correlation between social connections and food security motivations suggests that, while women who engage in UA for social connections may also have concerns about food security, the relationship is not strong or well-defined in this study. These findings contribute to a nuanced understanding of the motivations provided by the correlation coefficients, informing targeted interventions and policies that acknowledge the multifaceted nature of women's motivations in UA.

3.3.2. Determinants of motivations women’s participation in UA

This section presents the estimation results on factors that influence women’s motivations to participate in UA across the four dimensions of motivations: food security, economic reasons, social connections, and general well-being (see ).

Table 8. Multivariate probit model result on women’s motivations in UA.

Age plays a significant role in influencing women's motivations for participating in UA. The relationship between women's age and the likelihood of choosing motivation is positive for food security, social networking, and well-being, with a 1% level of significance. This implies that as women grow older, they are more likely to engage in UA to ensure food security, improve their well-being, and foster social connections. The positive association observed between age and food security motivation indicates that older women prioritize ensuring a consistent and dependable food supply for themselves and their families more than younger women do. This finding is consistent with Cheng et al. (Citation2016), who identified food security as an important issue for elderly people's quality of life and ageing in place. As a result, UA helps in provide affordable food in urban areas with limited access to fresh and healthy food (Colson-Fearon & Versey, Citation2022). Likewise, the positive correlation between age and motivation for social networking indicates that older women are more likely to seek social interaction through UA. This implies that older individuals place a higher value on social connections, and UA provides an avenue for fulfilling these needs. This discovery underscores the idea that community gardens and urban farming projects can serve as effective tools for promoting social cohesion and community development (Kirby et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the positive impact of age on motivation for well-being implies that as women age, they are more likely to find motivation in maintaining their health and reducing stress levels. This is because engagement in UA may improve their overall well-being by providing them with a sense of purpose, physical exercise, and a therapeutic outlet for stress relief. This is consistent with existing literature indicating that older individuals turn to urban farming to maintain health and manage stress (Othman et al., Citation2019). Conversely, the age-related negative coefficient for economic motivations suggests that younger women economic opportunities over those of older women. This finding aligns with previous research that suggests younger individuals may view UA as a potential source of income generation or entrepreneurial ventures (Alemu et al., Citation2022).

Education has a negative influence on the likelihood of choosing economic reasons and social connection motivations at the 1% and 5% significance levels, respectively. This suggests that educated women may be less motivated by economic gains and social connections through UA. This is possible because educated women already have job stability or financial security (Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019). Similarly, existing educational networks may replace the need for social connections through UA. A study by Adebisi and Monisola in 2012 supports this idea, suggesting that educated women tend to have diverse social interactions beyond urban agriculture.

Marital status has a significant positive impact on the likelihood of motivations for participating in UA for food security, well-being, and social connections at 5%, 1%, and 10% levels of significance, respectively. This implies that married women are more likely to engage in UA with the motivations of ensuring food security, enhancing their overall well-being, and establishing social connections. This suggests that married women are more committed to securing a stable food supply and prioritize the well-being of their families as compared to unmarried women. These findings align with those of Audate et al. (Citation2021), emphasizes the role of family dynamics in such agricultural practices.

The study’s findings also indicate that family size has significant and positive influences on the likelihood of choosing motivations for food security and economic reasons at 5% and 1% significance levels, respectively. This suggests that women from large families are more likely to engage in urban farming to meet increasing food demand, economize on costs, and generate income. The positive coefficient linked to family size indicates that women from large families are more motivated by food security than those from smaller ones. Larger families, with more individuals to feed, prioritize a stable food supply for their members. Mutiah and Istiqomah (Citation2017) reported a negative effect of household size on household food security, consistent with findings by Aidoo et al. (Citation2013), which indicate that larger households tend to be more food insecure compared to smaller ones. This finding is supported by Sangwan and Tasciotti (Citation2023) discovery that households with larger sizes are more likely to participate in UA. Likewise, the positive correlation between family size and economic reasons implies that larger families are more inclined to participate in urban farming considerations. This means that the connection between having larger families and potentially cheaper labour could be because larger families require more financial resources to meet their needs. Therefore, parents may rely on their children to work and contribute to the family’s income. This finding is consistent with Lee et al. (Citation2023), who discovered that larger households have greater labour resources to participate in UA. In this context, urban farming offers an additional income source and cost savings on purchasing fresh produce. These findings align with prior research, Adebisi and Monisola (Citation2012) observed that women farmers are primarily motivated by food security in response to rising prices of goods. involved in urban agriculture primarily for food security and as a response to increasing prices of goods.

At the 1% and 5% significance levels, women’s employment status has a positive association with the likelihood of choosing economic reasons and social connections motivations, respectively, while at the 10% significance level, it has negative impact on the likelihood of well-being motivation. This suggests that housewives are more likely to be motivated to participate in UA for economic opportunities and social connections compared to those employed outside the home. The positive impact on economic motivation implies that housewives are more likely to seek motivation to supplement their household income, potentially empowering themselves economically through UA participation instead of relying solely on their husbands’ income. Similarly, the positive effect on social connection motivation indicates that housewives may view UA as a means to engage with their community and foster social networks. On the other hand, the negative impact on well-being motivation suggests that women employed outside the home may fulfil their well-being needs by partially participating in UA, gaining physical and mental health improvements. These findings align with existing literature, such as the study by Gamhewage et al. (Citation2015), which found that housewives are more actively involved in UA compared to jobholders. Anderson et al. (Citation2021) and Safitri et al. (Citation2021) also support this idea, highlighting that housewives are motivated to actively participate in UA due to its numerous economic benefits and contribution to household income. However, the variable is insignificant for food security motivations.

Non-UA income demonstrates a significant negative correlation with the likelihood of food security and economic reasons motivations, both at the 5% significance level, and a positive relationship with the likelihood of well-being at the 10% significance level. The negative coefficient of non-UA income suggests that women with higher household incomes are less likely to practice UA for food security and economic gains. Previous studies have indicated that women with lower non-UA income sources are more likely to engage in UA for food security and economic reasons, encourage socio-economically disadvantaged women to adopt new dietary practices (Audate et al., Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2017), produce food (or income) in low-income urban communities (Diehl et al., Citation2019; Siegner et al., Citation2018), and provide significant food and income sources (Adebisi & Monisola, Citation2012; Hamilton et al., Citation2014). On the other hand, women with higher non-UA incomes are more likely to participate in UA for well-being reasons. Studies Audate et al. (Citation2019); Diekmann et al. (Citation2020) support this findings by highlighting the motivation of urban residents to engage in UA for their well-being, even when their non-urban income is high.

At the 5% level of significance, farming experience has a positive and significant influence effect on the decision to participate in UA for economic reasons and social connection motivations. This implies that women with greater farming experience are more likely to participate in UA for economic reasons and social connection motivations. This finding aligns with studies suggesting that individuals with more farming experience tend to use their social connections to improve their learning (Pratiwi & Suzuki, Citation2017). Similarly, Adebisi and Monisola (Citation2012) found that women's skills and experience in agricultural occupations positively influence their interest in urban farming. The size of the garden also positively and significantly influences the likelihood of economic reasons, social connection, and well-being motivations at the 1% level of significance. A larger garden correlates with increased engagement in UA for economic gains, enhanced social connections, and improved general well-being. This suggests that they may have the potential to invest more and generate income from selling produce. This aligns with previous studies by Diekmann et al. (Citation2020) and Kingsley et al. (Citation2019), which discovered that larger gardens offer increased agricultural production opportunities and foster community interactions, enhancing economic gains and social benefits. Chalmin-Pui et al. (Citation2021) also found that larger gardens positively impact overall well-being.

At the 1% level of significance, credit access positively influenced the likelihood of choosing economic reasons and social connection motivations, while at the 5% level of significance, it negatively influenced the likelihood of choosing food security motivations. This suggests that women with better credit access are more likely to engage in UA primarily for economic reasons and social connection motivations, with a relatively lower emphasis on food security. Having better access to credit may also indicate a higher level of financial stability and resources, making women more capable to investing in UA. Furthermore, the positive coefficient of social connection suggests that women with better credit access may have a strong incentive to engage in agricultural activities because they feel supported and connected to others who share similar interests and goals. Raney et al. (Citation2011) research aligns with this observation, highlighting that credit access empowers women to obtain essential resources and adopt contemporary farming practices.

Extension service exhibit a negative and significant association with the likelihood of choosing food security motivations, indicating women with better extension services are less likely to engage in UA for food security motivations. Better access to this service may encourage women to explore other motivations within urban agriculture. Finally, at the 1% level of significance, access to the market and improved inputs positively correlate with economic reasons and social connection motivations. This implies that women who have improved access to markets and high-quality agricultural inputs can boost their agricultural productivity and income. This aligns with the findings of Anderson et al. (Citation2021), emphasizing the crucial role of supporting women in agriculture through access to inputs for sustainable development and poverty reduction. This is because developed technical inputs, such as improved seeds, seedling technology, eco-friendly fertilizer, and pest control, accelerate agricultural production (Lee et al., Citation2023). Overall, these findings underscore the importance of age, education, family size, employment status, income, farming experience, credit access, gardening size, and extension services in influencing women's motivations for participating in UA, emphasizing the multi-faceted nature of urban agriculture dynamics.

4. Conclusion

This study examines the motivations for women's participation in UA and the socioeconomic factors influencing these motivations in Hossana town, Ethiopia. This study significantly contributes to the existing body of research on urban agriculture in Ethiopia. While the level of women's participation in urban agriculture has been the subject of numerous studies, quantitative research that examines the factors influencing women's motivations to participate in this context has been notably lacking. This research serves as a crucial step towards closing this research gap. Using a multivariate probit model, the study estimated the factors that influence women’s motivations to engage in urban agriculture across four motivational dimensions: food security, economic reasons, social connection, and general wellbeing. The study also delved into the characteristics and motivations of women who actively participate in urban agriculture in Hossana Town. The study's findings reveal most urban women in agriculture are married, housewives, have primary education, lower non-UA media income, belong to larger families, and grow vegetables and fruits. Multiple factors motivate women to participate in urban agriculture. The findings reveal that women participate in UA for multiple motivations; the most common are a pair of food security and economic reasons, as well as all four dimensions. Social connection and general well-being are not sufficient singular motivations for women in the study area.

The multivariate probit model result shows complementarity in most pairs of UA motivations studied, with the exception of general well-being and economic reasons. This suggests that women are mostly influenced by multiple motivations to participate in UA. The study concludes that factors influencing women’s motivations to participate in UA show diversity among motivations. Age, education level, marital status, family size, employment status, non-UA income, farm experience, garden size, credit access, market access, and improved inputs are all significant variables. Importantly, their impact varies in direction and magnitude across the four motivational dimensions. These are pertinent for policymakers and researchers who are interested in understanding women’s motivations to participate in UA and the factors that affect their motivations in the study area.

Our findings hold significant relevance for the development of policies and programmes aimed at more effectively supporting women's engagement in urban agriculture and enhancing their overall quality of life. For instance, policy initiatives that prioritize expanding women's access to land and essential resources, along with offering comprehensive training and education in urban agriculture, have the potential to boost women's participation across all motivational factors. Furthermore, this research’s notable strength lies in its contribution to addressing the scarcity of relevant studies that employ the multivariate probit model to investigate factors influencing motivations to participate in UA. This is particularly noteworthy because the existing body of research in this domain predominantly relies on descriptive and other econometric models, making direct comparisons challenging. However, it is important to acknowledge that our research encountered certain limitations and identified potential avenues for future research. In our study, we discovered motivations across four dimensions (food security, economic reasons, social connection, and general well-being) for women’s participation in UA. However, this study did not encompass the cultural, environmental, and personal aspirations that may motivate women to participate in UA. Future research should consider a more holistic approach to capture these diverse motivations. In addition, future research should investigate how motivations influence the types of UA practices women engage in, which can provide valuable insights for designing targeted interventions and policies to support diverse UA initiatives. This research can contribute to more effective urban agricultural development strategies.

Authors’ contribution

Both authors contributed to the study conception, writing, and editing. Tayech Lemma performed material preparation, data collection, analysis, and first draft writing. Dr. Mala Sharma provided supervision, review, and editing.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the women in Hossana Town, Ethiopia, who graciously took part in this study. Their valuable contributions and cooperation were crucial for the successful completion of this research. We also acknowledge the support and collaboration of community leaders and agricultural institutions in Hossana Town. Their guidance and assistance greatly facilitated our access to essential resources and data for this study.

Data availability statement

The research described in the paper did not utilize any data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abebe, B. A., & Yazie, B. (2019). Determinants of women’s participation in agricultural extension services among Rural Women Farmers in Yilmanadensa District, Northwest Ethiopia.

- Adebisi, A., & Monisola, T. A. (2012). Motivations for women involvement in urban agriculture in Nigeria.

- Aidoo, R., Mensah, J. O., & Tuffour, T. (2013). Determinants of household food security in the sekyere-afram plains district of Ghana.

- Alemu, A., Woltamo, T., & Abuto, A. (2022). Determinants of women participation in income generating activities: Evidence from Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-022-00260-1

- Anderson, C. L., Reynolds, T. W., Biscaye, P., Patwardhan, V., & Schmidt, C. (2021). Economic benefits of empowering women in agriculture: Assumptions and evidence. The Journal of Development Studies, 57(2), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1769071

- Audate, P. P., Cloutier, G., & Lebel, A. (2021). The motivations of urban agriculture practitioners in deprived neighborhoods: A comparative study of Montreal and Quito. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 62, 127171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127171

- Audate, P. P., Fernandez, M. A., Cloutier, G., & Lebel, A. (2019). Scoping review of the impacts of urban agriculture on the determinants of health. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 672. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6885-z

- Badami, M. G., & Ramankutty, N. (2015). Urban agriculture and food security: A critique based on an assessment of urban land constraints. Global Food Security, 4, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2014.10.003

- Bolang, P. D., & Osumanu, I. K. (2019). Formal sector workers’ participation in urban agriculture in Ghana: Perspectives from the Wa municipality. Heliyon, 5(8), e02230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02230

- Cappellari, L., & Jenkins, S. P. (2003). Multivariate probit regression using simulated maximum likelihood. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 3(3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0300300305

- Cattivelli, V. (2023). Review and analysis of the motivations associated with urban gardening in the pandemic period. Sustainability, 15(3), 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032116

- Chalmin-Pui, L. S., Griffiths, A., Roe, J., Heaton, T., & Cameron, R. (2021). Why garden? – Attitudes and the perceived health benefits of home gardening. Cities, 112, 103118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103118

- Cheng, Y., Rosenberg, M., Yu, J., & Zhang, H. (2016). Food security for community-living elderly people in Beijing, China. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(6), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12255

- Church, A., Mitchell, R., Ravenscroft, N., & Stapleton, L. M. (2015). ‘Growing your own’: A multi-level modelling approach to understanding personal food growing trends and motivations in Europe. Ecological Economics, 110, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.12.002

- Colson-Fearon, B., & Versey, H. S. (2022). Urban agriculture as a means to food sovereignty? A case study of baltimore city residents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12752. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912752

- CSA. (2014). Central statistical agency of Ethiopia. Demographic and Health survey projected.

- Delelegn, M., & Mulugeta, M. (2018). The status of urban agriculture in and around Addis Ababa. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 20(2), 128–147.

- Diehl, J., Oviatt, K., Chandra, A., & Kaur, H. (2019). Household food consumption patterns and food security among low-income Migrant urban farmers in Delhi, Jakarta, and Quito. Sustainability, 11(5), 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051378

- Diekmann, L. O., Gray, L. C., & Thai, C. L. (2020). More than food: The social benefits of localized urban food systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 534219. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.534219

- EM. (2023). Green legacy initiative: Focus on fruits as tree seedlings preparation begins.

- FAO. (2023). The status of women in agrifood systems. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc5343en.

- FSIN. (2022). Global report on food crises—2022. https://www.wfp.org/publications/global-report-food-crises-2022

- Gamhewage, M. I., Sivashankar, P., Mahaliyanaarachchi, R. P., Wijeratne, A. W., & Hettiarachchi, I. C. (2015). Women participation in urban agriculture and its influence on family economy – Sri Lankan experience. Journal of Agricultural Sciences – Sri Lanka, 10(3), 192–206. https://doi.org/10.4038/jas.v10i3.8072

- Gebremedhin, S., Reta, F., Seifu, H., Baye, K., Sergawi, A., & Zelalem, M. (2023). Situational analysis of urban agriculture in Addis Ababa, and feasibility of integrating urban agriculture with social protection programs for improving access of the urban poor to healthy foods: Qualitative study. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/62098

- Grebitus, C., Chenarides, L., Muenich, R., & Mahalov, A. (2020). Consumers’ Perception of urban farming—An exploratory study. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 79. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00079

- Green, W. (2002). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Greene, W. (2012). Econometric analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hadebe, L. B., & Mpofu, J. (2013). Empowering women through improved food security in urban centers: A gender survey in Bulawayo urban agriculture.

- Hamilton, A. J., Burry, K., Mok, H.-F., Barker, S. F., Grove, J. R., & Williamson, V. G. (2014). Give peas a chance? Urban agriculture in developing countries. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 34(1), 45–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-013-0155-8

- Hovorka, A. J. (2006). Urban agriculture: Addressing practical and strategic gender needs. Development in Practice, 16(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520500450826

- HTFAED. (2014). Hossana town finance and economic development office: Socio-economic profile of Hossanatown. Unpublished document.

- Khalil, H., & Al Najar, H. (2021). The role of the urban agriculture on food security during armed conflicts in the Gaza Strip. Journal of Emergency Management, 19(5), 493–503. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.0544

- Kingsley, J., Foenander, E., & Bailey, A. (2019). “You feel like you’re part of something bigger”: Exploring motivations for community garden participation in Melbourne, Australia. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 745. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7108-3

- Kirby, C. K., Goralnik, L., Hodbod, J., Piso, Z., & Libarkin, J. C. (2020). Resilience characteristics of the urban agriculture system in Lansing, Michigan: Importance of support actors in local food systems. Urban Agriculture & Regional Food Systems, 5(1), e20003. https://doi.org/10.1002/uar2.20003

- Kirby, C. K., Specht, K., Fox-Kämper, R., Hawes, J. K., Cohen, N., Caputo, S., Ilieva, R. T., Lelièvre, A., Poniży, L., Schoen, V., & Blythe, C. (2021). Differences in motivations and social impacts across urban agriculture types: Case studies in Europe and the US. Landscape and Urban Planning, 212, 104110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104110

- Lambert, E., & Orkaido, K. (2023). The role of green legacy in promoting sustainable development and combating climate change. Qeios. https://doi.org/10.32388/DDSZT6

- Lee, S., Shin, S., Lee, H., & Park, M. S. (2023). Which urban agriculture conditions enable or constrain sustainable food production? International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 21(1), 2227799. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2023.2227799

- Martin, P., Consalès, J.-N., Scheromm, P., Marchand, P., Ghestem, F., & Darmon, N. (2017). Community gardening in poor neighborhoods in France: A way to re-think food practices? Appetite, 116, 589–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.05.023

- McNicoll, K. (2011). Women feeding cities: Mainstreaming gender in urban agriculture and food security. Development in Practice, 21(1), 133–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2011.530234

- Mok, H.-F., Williamson, V. G., Grove, J. R., Burry, K., Barker, S. F., & Hamilton, A. J. (2014). Strawberry fields forever? Urban agriculture in developed countries: A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 34(1), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-013-0156-7

- Muriuki, J., Hudson, D., & Fuad, S. (2023). The impact of conflict on food security: Evidence from household data in Ethiopia and Malawi. Agriculture & Food Security, 12(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-023-00447-z

- Mutiah, S. A., & Istiqomah, I. (2017). Determinants of household food security in urban areas. JEJAK, 10(1), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.15294/jejak.v10i1.9130

- Nega, T. (2023, June 13). How an urban agriculture project in ethiopia is improving lives and regreening communities—Farming first. Farming First. https://farmingfirst.org/2023/05/how-an-urban-agriculture-project-in-ethiopia-is-improving-lives-and-regreening-communities/

- Olivier, D. W. (2019). Urban agriculture promotes sustainable livelihoods in Cape Town. Development Southern Africa, 36(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2018.1456907

- Othman, N., Latip, R. A., & Ariffin, M. H. (2019). Motivations for sustaining urban farming participation. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 15(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJARGE.2019.099799

- Pollard, G., Roetman, P., Ward, J., Chiera, B., & Mantzioris, E. (2018). Beyond productivity: Considering the health, social value and happiness of home and community food gardens. Urban Science, 2(4), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2040097

- Poulsen, M. N., McNab, P. R., Clayton, M. L., & Neff, R. A. (2015). A systematic review of urban agriculture and food security impacts in low-income countries. Food Policy, 55, 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.07.002

- Pratiwi, A., & Suzuki, A. (2017). Effects of farmers’ social networks on knowledge acquisition: Lessons from agricultural training in rural Indonesia. Journal of Economic Structures, 6(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-017-0069-8

- Raney, T., Anriquez, G., Croppenstedt, A., Gerosa, S., Lowder, S., Matuscke, I., & Skoet, J. (2011). The role of women in agriculture.

- FAO, & Rikolto, R. (2022). Urban and peri-urban agriculture sourcebook- From production to food systems. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb9722en.

- Safitri, K. I., Abdoellah, O. S., & Gunawan, B. (2021). Urban farming as women empowerment: Case Study Sa’uyunan Sarijadi Women’s farmer group in Bandung City. E3S Web of Conferences, 249, 01007. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202124901007

- Sangwan, N., & Tasciotti, L. (2023). Losing the plot: The impact of urban agriculture on household food expenditure and dietary diversity in sub-Saharan African Countries. Agriculture, 13(2), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13020284

- Scheromm, P. (2015). Motivations and practices of gardeners in urban collective gardens: The case of Montpellier. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 14(3), 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.02.007

- Siegner, A., Sowerwine, J., & Acey, C. (2018). Does urban agriculture improve food security? Examining the nexus of food access and distribution of urban produced foods in the United States: A systematic review. Sustainability, 10(9), 2988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092988

- Tapia, C., Randall, L., Wang, S., & Aguiar Borges, L. (2021). Monitoring the contribution of urban agriculture to urban sustainability: An indicator-based framework. Sustainable Cities and Society, 74, 103130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103130

- UN. (2019). World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision. United Nations.

- Yalew, A. W. (2020). Urban agriculture in Ethiopia: An overview. Regional Economic Development Research, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.37256/redr.122020607

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Harper and Row. http://www.sciepub.com/reference/180098

- Zhou, Y., Wei, C., & Zhou, Y. (2022). How does urban farming benefit participants? Two case studies of the Garden City Initiative in Taipei. Land, 12(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010055