KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

Since the first use of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) in 1999, this regimen of chemoimmunotherapy has been the backbone of first-line treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Long-term follow-up (about 13 years) of the MDACC phase 2 FCR study, results of phase 3 German CLL Study Group’s CLL8 study and a recently published systematic review qualify FCR as the best available treatment for patients with low-risk genetic features [i.e., mutated IGHV status and lack of del(11q) and del(17p)]. With FCR these patients have a particularly favorable clinical outcome suggestive of functional cure [Citation1–3]. Interestingly, patients who achieved undetectable minimal residual disease (MRD) at the end of therapy benefited in terms of longer PFS [Citation4].

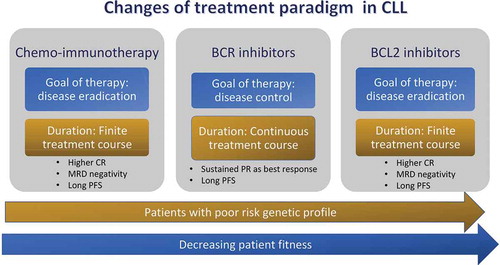

Results obtained with FCR regimen cannot be applied to elderly. They carry several challenges including a higher risk of infections and individual differences in comorbidities and geriatric syndromes [Citation5]. Less intensive chemoimmunotherapy regimens such as bendamustine and rituximab (BR) [Citation6] or chlorambucil and obinutuzumab [Citation7] are better tolerated by older fit and unfit patients, respectively. However, with a mitigated approach of chemoimmunotherapy, myelotoxicities can occur mainly due to age-related decline of the hematopoietic reserve. Several active and oral agents have emerged that target key proximal kinases in the B-cell receptor (BCR) pathway, including Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) [Citation8,Citation9]. Venetoclax, an antagonist of BCL-2 protein, induces high response rates and durable remissions in the relapsed/refractory (R/R) and frontline settings with an acceptable profile toxicity [Citation10]. With these agents toxicity profiles have been mild without significant myelosuppression over prolonged dosing. Of note, the extensive use of these novel compounds resulted in a change of treatment paradigm in the care of CLL from unspecific DNA-damaging agents to ‘targeted therapy.’

2. Continuous therapy with ibrutinib: the first change of treatment paradigm

Clinical trials of agents targeting BTK, a crucial downstream component of BCR, have represented a major breakthrough in the treatment of CLL [Citation8,Citation11]. In the final analysis of RESONATE trial, with up to 6 years of follow-up, patients with R/R disease experienced a significant sustained, PFS benefit with ibrutinib versus ofatumumab (44.1 versus 8.1 months). Safety remained acceptable, with low rates of discontinuation and no new safety signals emerged during long-term therapy [Citation8].

In 2016, ibrutinib was also approved as a single agent for first-line treatment in older patients with CLL. According to results of RESONATE2 phase 3 trial, treatment with ibrutinib translated into a long-term PFS benefit in comparison to chlorambucil [Citation12]. However, data from RESONATE-2, should not be considered conclusive because chlorambucil as a single agent is a very uncommon treatment for CLL nowadays [Citation12]. Three different phase 3, randomized, clinical studies have compared in upfront the effectiveness of ibrutinib-based regimens with chemo-immunotherapy in CLL patients [Citation13–15]. The National Cancer Institute (NCI)-sponsored trial enrolled older patients who were randomly assigned to receive ibrutinib, ibrutinib plus rituximab (IR), or BR. PFS at 2 years for patients receiving ibrutinib alone or IR were 87% and 88%, respectively, compared with 74% in the BR cohort, while there were no significant differences in overall survival (OS). The results also suggest that adding rituximab to ibrutinib does not improve the ibrutinib efficacy [Citation13]. In the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group, 529 patients younger than 70 years were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive IR or FCR. Compared with FCR, IR reduced the risk of disease progression and death by 65% and 83%, respectively, and was associated with less severe side effects [Citation14]. Finally, the iLLUMINATE, is an industry-sponsored study comparing ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab to chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in untreated CLL/SLL patients ≥ 65 or younger patients with co-morbidities [Citation15]. PFS at 30 months in the ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab group was significantly longer than in chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab group (79% vs 31%). In this study, however, the benefit of adding obinutuzumab is not clear because a third arm with ibrutinib monotherapy was not evaluated [Citation15].

3. Pitfalls of therapy with ibrutinib

Results of aforementioned trials imply a change of treatment paradigm toward an indefinite duration of therapy. However, in both clinical trials and real-world analyses, intolerance, particularly due to cardiac dysrhythmias and increased risk of bleeding, appears to be the main reason for ibrutinib discontinuation in about 30% of patients [Citation8,Citation11–16]. The analysis of a large CLL cohort indicates that 78.3% of patients taking ibrutinib developed new or worsening hypertension. Major adverse cardiovascular events, including arrhythmias, occurred in 16.5% of patients and were more common in patients with hypertension [Citation17]. Second-generation BTK inhibitors have been designed to overcome toxicities of ibrutinib. Acalabrutinib, a novel irreversible second-generation BTK inhibitor, has been recently evaluated in phase 3 trials of R/R CLL and treatment-naïve patients [Citation18,Citation19]. ASCEND is a phase III study demonstrating a statistically significant and clinically meaningful PFS with acalabrutinib compared with idelalisib + Rituximab or B-R, together with a tolerable safety profile, in patients with R/R CLL [Citation18]. ELEVATE-TN study compared chlorambucil-obinutuzumab versus acalabrutinib alone versus acalabrutinib plus obinutuzumab in upfront [Citation19]. Acalabrutinib alone or acalabrutinib-obinutuzumab significantly improved PFS along with a 2-year PFS rate of about 90%. In the acalabrutinib monotherapy arm (n = 179), the most common AEs of any grade (30%) included headache (36.9%) and diarrhea (34.6%). Of note, there appears to be a beneficial trend with the addition of obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib, which demonstrates, for the first time, the potential PFS benefit of adding obinutuzumab to a BTK inhibitor even though the study was not powered for this endpoint [Citation19].

Zanubrutinib (BGB-3111) is another highly selective BTK inhibitor with better oral bioavailability than ibrutinib. Like ibrutinib, zanubrutinib covalently binds to cysteine 481 in the adenosine triphosphate – binding domain of BTK. Extended follow-up of 122 CLL patients (including 22 treatment naïve and 100 R/R patients) has been presented at the recent American Society Hematology (ASH) meeting [Citation20]. With a median follow-up of 25.1 months, the ORR was 97% ant the CR rate was 14%. Median PFS was not reached (PFS rate at 1 year was 97%). Treatment has been discontinued in 17% of patients (11% due to PD). The most common AEs were contusion (46%; 41% grade 1), upper respiratory tract infection (39%) and diarrhea (30%). The most common serious AE was pneumonia (6%) [Citation20].

Another relevant problem with ibrutinib is the development of ibrutinib-resistant CLL clones which occur in about 20% of patients [Citation21]. Ibrutinib binds to BTK at the cysteine 481 residue (C481), and cysteine to serine mutations (C481S) occurring at this ligand site followed by mutations in phospholipase Cg2 (PLCG2) are mainly responsible for mechanism of resistance especially in patients with high-risk disease [Citation22]. In this setting, it would be important to consider future strategies aimed at evaluating the clinical impact of early detection of BTK mutations with a prompt switch to noncovalent BTK inhibitors (i.e., vecabrutinib, LOXO-305)(reviewed by Molica et al) [Citation23].

Finally, it is important to be aware of the ‘financial toxicities’ associated with a recommended ‘life-long’ treatment. Costs related to continuous therapy with ibrutinib weight not only on patient but also on health systems for publicly funded institutions. A recent study suggests that introducing a time-limited therapy with venetoclax and obinutuzumab in the first-line CLL treatment resulted in significant cost saving compared to chemoimmunotherapies and ibrutinib-based therapies [Citation24].

4. Time-limited therapy with venetoclax in CLL: the second change in treatment paradigm

Toxicities, inevitable resistance, and the growing cost of indefinite therapy with BTK inhibitors have represented a robust argument to investigate time-limited combination therapy of targeted agents. To date, the MURANO and CLL14 trials represent the most established steps toward time-limited combination, achieving deep remissions for the majority of patients. MURANO trial enrolled relapsed CLL patients assigned to receive randomly venetoclax for up to 2 years plus rituximab (VR) for the first 6 months versus BR for 6 cycles [Citation10]. After a 4-year follow-up results indicate a sustained PFS benefit for patients treated with VR in comparison to those receiving BR (57% versus 4.6%). Similarly, an OS advantage was observed with VR despite three-quarters of patients progressing after BR received treatment with a novel-targeted agents [Citation25]. At the end of treatment, 64% of patients enrolled in VR arm had achieved undetectable MRD, and 87% of these patients remained free of disease progression 2-years post-treatment.

CLL14 is a multicenter trial designed to demonstrate superiority of time-limited (given for one year) therapy of venetoclax and obinutuzumab (VO) over standard chlorambucil and obinutuzumab (CO) in untreated patients with active disease and relevant comorbidities. While no difference was found with respect to safety between regimens, VO outperformed CO in terms of CR, ORR, undetectable MRD (uMRD) and PFS [Citation26]. On the basis of these results, the EMA and the FDA approved the combination of fixed-duration VO for the treatment of patients with previously untreated CLL.

5. Venetoclax rehabilitates MRD as a suitable surrogate endpoint

MRD quantification is a well-established independent prognostic marker of PFS and overall survival (OS) after chemoimmunotherapy in CLL [Citation27]. However, the role of MRD as predictor of longer PFS and OS has been abrogated by BTK inhibitors [Citation8,Citation11–16]. Ibrutinib, given as continuous therapy, has led to prolonged PFS and OS in R/R and treatment naïve CLL but clinical responses are rarely complete [Citation8,Citation11–16]. More recently, chemo-free combinations of venetoclax+rituximab and venetoclax+obinutuzumab have been shown capable of inducing uMRD in the bone marrow (BM), opening the way to protocols exploring strategies of MRD-driven duration of treatment [Citation10,Citation26].

However, while the relevance of MRD assessment as a surrogate endpoint in clinical trials is unquestionable, its role in routine clinical practice has not yet been well defined.

The effort of European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC) to standardize methods for MRD detection by flow cytometry will certainly contribute to make more affordable and accessible in the routine clinical setting MRD assessment [Citation28]. In 2016, the EMA accepted the use of undetectable MRD as a surrogate for PFS and as an intermediate endpoint in CLL trials [Citation29].

6. Pitfalls of therapy with venetoclax

The introduction of fixed time chemo-free therapy introduced with MURANO and CLL14 trials raises some practical questions. Firstly, it is not clear whether a fixed period (i.e., two-year for MURANO trial, one year for CLL14 trial) of exposure to venetoclax is a suitable approach for all patients with CLL or a subset of patients with sub-optimal response and/or high-risk genetic features may potentially benefit from a longer duration of therapy. Secondly, the optimal management of patients who discontinue venetoclax is unknown. While the efficacy of venetoclax after BTKi failure has been extensively reported, data for the opposite sequence are limited [Citation30,Citation31]. Recent results indicate that patients who discontinue venetoclax may benefit from treatment with BTK inhibitors provided that they are BTK inhibitors treatment-naïve [Citation32,Citation33]. In an international, multicenter, retrospective cohort, efficacy of BTK inhibitor monotherapy does not seem to be compromised by prior venetoclax treatment. Patients achieved an 84% ORR with a median PFS of 32 months providing that they had not been previously treated with BTK inhibitors [Citation32]. A recently published retrospective study including 23 consecutive patients with R/R CLL who received a BTK inhibitor after stopping venetoclax because of progressive disease reached similar conclusions. Interestingly, prior remission duration ≥24 months on venetoclax was associated with longer PFS after BTKi salvage [Citation33]. Thirdly, in absence of clinical trials directly comparing venetoclax versus venetoclax plus rituximab in CLL the efficacy of adding rituximab to venetoclax is not proven. A multicenter, retrospective study compared the outcome of patients with R/R CLL treated with venetoclax versus venetoclax plus rituximab [Citation34]. Results in terms ORR,CR and PFS appeared comparable between the two groups. In absence of a direct comparison it is reasonable to maintain the association of venetoclax and rituximab (i.e., MURANO trial) or obinutuzumab (i.e., CLL14 trial). The absence of additional toxicities caused by anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies and the aim to achieve the deeper response possible in the context of a time-limited therapy justify such an approach.

Finally, resistance mechanisms have been observed in CLL patients treated with venetoclax [Citation35].They include: (1) the acquisition of a BCL2 mutation (Gly101Val) that reduces venetoclax binding to BCL29,10; and (2) overexpression of other pro-survival proteins BCL-XL and MCL1 [Citation35,Citation36]. It is expected that identification of BCL2 mutations responsible of resistance to venetoclax will result in

development of new agents targeting other molecules in the apoptosis pathway such as MCL-1 [Citation37].

7. Conclusions

Nowadays, with maturing experience related to the use of continuous single-targeted agent, several common arguments have emerged. Generally, toxicities, expected resistance, cost of indefinite therapy represent a robust argument for considering time-limited combination therapy a reliable approach in several patients. Results of MURANO and CLL14 trials which provide deep remission for the majority of patients appear mature for being translated into clinical practice.

8. Expert opinion

Preliminary data from ibrutinib-venetoclax combination in high-risk or elderly treatment-naïve patients indicate that 79% of patients can achieve BM undetectable MRD status [Citation38]. Similar rates of BM undetectable MRD achievement (73%) were obtained after 12 cycles of ibrutinib-venetoclax treatment in younger treatment-naïve patients enrolled in the CAPTIVATE study [Citation39]. A Phase I trial of 12-month fixed duration venetoclax-ibrutinib-obinutuzumab in R/R patients reported a 50% BM undetectable MRD at the completion of treatment [Citation40]. An extended follow up is required to determine the proper role of these associations. Meanwhile, new questions are emerging regarding the optimal combination, duration of therapy, predictors of therapy discontinuation and chance of re-treatment. In particular, it is not clear whether MRD-guided treatment approaches will guide clinical practice in the next future, allowing for a more individualized therapy. Accordingly, are eagerly awaited results of phase 3 trials designed to investigate the efficacy and safety of adding venetoclax to the currently established regimen of obinutuzumab–ibrutinib in the frontline setting for patients older than age 70 years (Alliance; NCT03737981) and those age 18 to 69 years (ECOG; NCT03701282). The German CLL group has announced the launch of the upcoming CLL17 trial investigating the efficacy and safety of single-agent ibrutinib compared with venetoclax–obinutuzumab compared with ibrutinib plus venetoclax. Results of these studies, when available, will definitively provide an answer to the clinical relevance of change of treatment paradigm in CLL from continuous to time-limited ().

Declaration of interest

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

A peer reviewer on this manuscript has received research funding from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Juno, Novartis, Pharmacyclics and TG Therapeutics; and received honorarium for advisory board or lecturing for Abbvie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Kite, and Pharmacyclics. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Thompson PA, Tam CS, O’Brien SM, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab treatment achieves long-term disease-free survival in IGHV-mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016 Jan 21;127(3):303–309.

- Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–1174. .

- Chai-Adisaksopha C, Brown JR, Achieves Long-Term FCR. Durable remissions in patients with IGHV-mutated CLL. Blood. 2017 Nov 23;130(21):2278–2282.

- Bottcher S, Ritgen M, Fischer K, et al. Minimal residual disease quantification is anindependent predictor of progression-free and overall survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multivariate analysis from the randomized GCLLSG CLL8 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:980–988.

- Thurmes P, Call T, Slager S, et al. Comorbid conditions and survival in unselected, newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(1):49–56. .

- Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Bahlo J, et al. German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG). First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL10): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:928–942.

- Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1101–1110.

- Munir T, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al., Final analysis from RESONATE: up to six years of follow-up on ibrutinib in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(12):1353–1363. .

- Sharman JP, Coutre SE, Furman RR, et al. Final results of a randomized, phase III study of rituximab with or without idelalisib followed by open-label idelalisib in patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Jun 1;37(16):1391–1402.

- Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, et al., Venetoclax-rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1107–1120. .

- Byrd JC, Hillmen P, O’Brien S, et al. Long-term follow-up of the RESONATE phase 3 trial of ibrutinib vs ofatumumab. Blood. 2019 May 9;133(19):2031–2042.

- Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 17;373(25):2425–2437.

- Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2517–2528. .

- Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, et al., Ibrutinib-rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(5):432–443. .

- Moreno C, Greil R, Demirkan F, et al. Ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab in first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (iLLUMINATE): a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):43–56. .

- Mato AR, Thompson M, Allan JN, et al. Real-world outcomes and management strategies for venetoclax-treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients in the United States. Haematologica. 2018 Sep;103(9):1511–1517. .

- Dickerson T, Wiczer T, Waller A, et al. Hypertension and incident cardiovascular events following ibrutinib initiation. Blood. 2019 November;134(22):1919–1928. .

- Ghia P, Pluta A, Wach M, et al. ASCEND: phase III, randomized trial of acalabrutinib versus idelalisib plus rituximab or bendamustine plus rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Sep 1;38(25):2849–2861. Online ahead of print.

- Sharman JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, et al. Acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil and obinutuzmab for treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (ELEVATE TN): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020 Apr 18;395(10232):1278–1291.

- Cull G, Simpson D, Opat S, et al. Treatment with the bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor zanubrutinib (BGB-3111) demonstrates high overall response rate and durable responses in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL): updated results from a Phase 1/2 Trial. [Abstract]. Blood. 2019;134(S1):500.

- Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Guinn D, et al., BTKC481S- mediated resistance to ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(13):1437–1443. .

- Woyach JA. How I manage ibrutinib-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129(10):1270–1274.

- Molica S, Matutes E, Tam C, et al. Ibrutinib in the Treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: 5 Years On. Hematol Oncol. 2020 Apr;38(2):129–136.

- Cho SK, Manzoor BS, Sail KR, et al. Budget impact of 12-month fixed treatment duration venetoclax in combination with obinutuzumab in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020 May 8;38:941–951. Online ahead of print.

- Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst BF, et al. Four-year analysis of murano study confirms sustained benefit of time-limited venetoclax-rituximab (VenR) in relapsed/refractory (R/R) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Blood. 2019;134(Supplement_1):355 Abstr. .

- Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(23):2225–2236.

- Molica S, Giannarelli D, Montserrat E. Minimal residual disease and survival outcomes in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(7):423–430.ù.

- Rawstron AC, Böttcher S, Letestu R, et al. European Research Initiative in CLL. Improving efficiency and sensitivity: European Research Initiative in CLL (ERIC) update on the international harmonised approach for flow cytometric residual disease monitoring in CLL. Leukemia. 2013;27:142–149.

- European medicines agencyeappendix 4 to the guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man-condition specific guidance. [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_ content_001124.jsp&mid¼.

- Jones JA, Mato AR, Wierda WG, et al. Venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia progressing after ibrutinib: an interim analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(1):65–75. .

- Coutre S, Choi M, Furman RR, et al. Venetoclax for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who progressed during or after idelalisib therapy. Blood. 2018;131(15):1704–1711. .

- Mato AR, Roeker LE, Jacobs R, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of therapies following venetoclax discontinuation in CLL reveals BTK inhibition as an effective strategy. Clin Cancer Res 2020 Jul 15;26(14):3589–3596.

- Lin VS, Lew TE, Sasanka M, et al. BTK inhibitor therapy is effective in patients with CLL resistant to venetoclax. Blood. 2020;135(25):2266–2270.

- Mato AR, Roeker LE, Eyre TA, et al. A retrospective comparison of venetoclax alone or in combination with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody in R/R CLL. Blood Adv. 2019 May 28;3(10):1568–1573.

- Blombery P. Mechanisms of intrinsic and acquired resistance to venetoclax in B-cell lymphoproliferative disease. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020 Feb;61(2):257–262.

- Blombery P, Anderson MA, Gong JN, et al. Acquisition of the recurrent Gly101Val mutation in BCL2 confers resistance to venetoclax in patients with progressive chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(3):342–353. .

- Parikh SA, Gale RP, Kay NE. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 2020: a surfeit of riches? Leukemia. 2020 Aug;34(8):1979–1983.

- Jain N, Keating M, Thompson P, et al. Ibrutinib and venetoclax for first-line treatment of CLL. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(22):2095–2103.

- Tam CS, Siddiqi T, Allan JN, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma: results from the MRD cohort of the phase 2 CAPTIVATE study. Blood. 2019;135(Suppl 1):Abstract 35.

- Rogers KA, Huang Y, Ruppert AS, et al. Phase 1b study of obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, and venetoclax in relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2018;132:1568–1572.