For several decades, researchers have sought to divide breast cancer patients into meaningful subgroups with the intention of refining treatment strategies – to find the right drug for the right patient. The initial classifications were based on histology and included ductal, lobular, medullary and a few uncommon subtypes. It was then noted that lobular cancers are more resistant to cytotoxic chemotherapies than were the more common ductal cancers [Citation1]. In the 1980s, a second set of parameters was introduced, based on the expression of the hormone receptors ER and PR as well as the HER2 oncogene. Hormone-positive cancers respond to anti-hormonal therapies including SERMS, aromatase inhibitors and ovarian suppression (oophorectomy and pharmaceutical suppression) and the HER2-positive cancers respond well to anti-HER2 antibodies, such as Herceptin and more recently to antibody-drug conjugates such as trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd). Further classifications were determined by gene expression profiling (mRNA and proteins) and are used to define groups such as basal, luminal (A and B) normal-like and HER2-enriched [Citation2]. Other important subgroups include patients with inherited gene mutations, such as BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM. There may be considerable overlap of the groups, for example luminal cancers feature hormone receptor expression and cancers in BRCA1 mutation carriers typically exhibit basal-like features [Citation3].

Triple-negative breast cancer is probably the most widely studied (and most challenging) subgroup (over 3000 papers published per year). These are cancers whose cells lack the hormone receptors ER and PR and lack amplification or over-expression of HER2. The designation of triple-negative status is canonical because the three antigens are assayed in nearly every modern pathology lab for nearly every case. Triple-negative cancers are similar to, but not synonymous with the basal sub-type of breast cancer which is assessed using RNA expression – which is not a standard of clinical care.

Triple-negative cancers comprise about 15% of all breast cancers, but are over-represented in young women, in black women and in women with BRCA1 mutations. They are under-represented in Asians and in women with CHEK2 mutations and in lobular cancers. Among black women, they account for 29% of cancers and among BRCA1 carriers they account for 75% of cancers. The PARP inhibitor olaparib is now approved for use in BRCA1 carriers with triple-negative cancers in many developed countries. For this reason, there is an emerging view that all women with triple-negative cancers should be offered genetic testing. Up to 15% of women with triple-negative cancer will have a BRCA1 mutation [Citation4–6], but this proportion is higher in young women [Citation6]. In a recent study from Ontario, triple-negative status was the single most informative criterion for finding BRCA1 carriers [Citation4].

There are few known risk factors for triple negative cancer. Reproductive and hormonal risk factors – such as oral contraceptive use and hormone replacement therapy seem to have little impact on the risk of triple negative cancers. In one study, a higher risk of basal-like breast cancer was found with increasing parity, lack of breastfeeding and a high waist-hip ratio [Citation7].

There are few options for prevention. Trials of chemoprevention drugs, which include SERMS (tamoxifen and raloxifene) and aromatase inhibitors (exemestane and anastrozole) have consistently shown a reduction in the incidence of ER-positive cancers in post-menopausal women, but not of ER-negative cancers.

The only current preventive approach is risk-reducing mastectomy, but few women are at a high enough risk to justify the intervention and surgical prevention is mainly restricted to women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. In most cases, the cancers in BRCA1 carriers are triple-negative. In a recent paper, we observed a non-significant reduction in the incidence of breast cancer in healthy BRCA1 carriers who took preventive tamoxifen or raloxifene (hazard ratio = 0.65 (95%CI 0.35–1.22; p = 0.19)) [Citation8]. We did not classify the incident cancers by ER-status and further studies to explore a potential protective effect are warranted. Interestingly in an earlier study of BRCA1 carriers, oophorectomy was found to be associated with a strong reduction in breast cancer mortality [Citation9], and was equally effective in triple negative patients as in ER-positive patients. To our knowledge a benefit from oophorectomy has not been seen in triple-negative patients without a mutation and there are no preventive options specifically for this type of cancer.

Among triple-negative cancers, adverse prognostic factors include black race, young age, tumor size, the number of nodes involved and tumor grade. The presence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is protective [Citation10]. One often hears of triple negative cancers having a poor prognosis; the five year survival and overall survival are poor compared to other forms of breast cancer. True, but it is important to note that the majority of triple-negative cancers which recur will do so in the first five years after diagnosis – if a patient has not recurred by five years they are unlikely to recur later on [Citation11]. This is not the case for ER-positive cancers which seem to recur indefinitely. In practical terms, if a woman is a five-year survivor of breast cancer, her prognosis is better if she is triple-negative than if she is ER-positive. We and others have ascribed the different recurrent patterns to different rates of reactivation from tumor dormancy [Citation12].

We often hear that the lack of [Citation13] the three antigens make them not susceptible to targeted therapies, but this view is changing as new targets are being identified. Newer drugs include the PARP inhibitor olaparib which targets synthetic lethality and pembrolizumab (which is an immunotherapeutic antibody targeting PD-1). A compendium of the drugs now used to fight triple-negative cancer is provided in references 13 and 14.

The oncologist faces several clinical scenarios and in each scenario the treatment choice may differ. Many early-stage triple-negative patients are recommended to have neoadjuvant immune-chemotherapy [Citation14]. Currently, if a woman achieves a pathological complete response (pCR) she does not require further chemotherapy, but continues maintenance immunotherapy. The majority of deaths will occur in women who fail to achieve a pCR and this group demands our attention. In non-carriers who do not receive pembrolizumab, capecitabine is the drug of choice post neo-adjuvant. In BRCA1 carriers, it is not yet clear if capecitabine or olaparib is superior [Citation14,Citation15], as these drugs have not been compared head-to-head in a randomized trial. Other high-risk groups include women with de novo metastatic disease and women who experience a distant recurrence after an early-stage breast cancer. Standard chemotherapy for early-stage triple negative cancers now include a combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy whereby pembrolizumab is added to doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, a taxane and a platinum as per the Keynote 522 trial [Citation16].

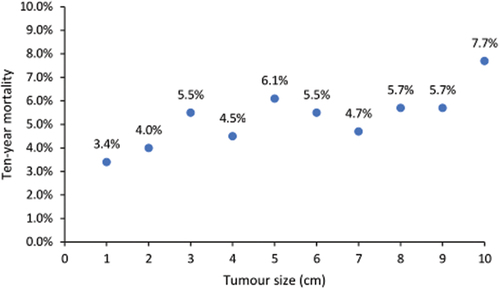

In general, almost all triple-negative cases are candidates for chemotherapy. The exception is those with node-negative tumors under 0.5 cm. In , we show that the ten-year mortality for women with node-negative, triple-negative breast cancer under 1 cm is nearly uniform across the size range and is less than 10%. The ten-year mortality among women with node-negative triple-negative cancer under 1 cm in SEER was 5.1% for those who received chemotherapy vs. 5.9% for those who did not. Among young black women (<40 years) with node-negative, triple-negative breast cancers under 1 cm in size, the 10-year breast cancer mortality rate is 10.1%. It would be valuable to find a signature that would be predictive of mortality of 10% or greater among women with small triple-negative breast cancers as these patients might potentially benefit from chemotherapy. Prognostic factors could include black race, BRCA1 mutation status, lack of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, young age and possibly gene expression signatures. It is not clear why ovarian suppression is beneficial in the hereditary subgroup of triple negative cancers. I think we should consider the possibility that other subgroups of triple-negative breast cancer patients (besides BRCA1 carriers) might benefit from oophorectomy as well. It is also important that a greater number of women with triple negative breast cancer should have genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2. Among mutation-positive women who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the majority of deaths occur in women who fail to achieve a complete pathologic response. Future studies should compare various treatments for women in this high risk group. At the other end of the spectrum we see that small triple-negative cancers with a high concentration of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes have a very good prognosis and may be candidates for de-escalation of chemo and immunotherapy [Citation17].

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Davey MG, Keelan S, Lowery AJ, et al. The impact of chemotherapy prescription on long-term survival outcomes in early-stage invasive lobular carcinoma - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2022 Dec;22(8):e843–e849. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2022.09.005

- Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000 Aug 17;406(6797):747–752.

- Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Nov 11;363(20):1938–1948.

- Metcalfe KA, Narod SA, Eisen A, et al. Genetic testing women with newly diagnosed breast cancer: what criteria are the most predictive of a positive test? Cancer Med. 2023 Mar [Epub 2022 Dec 21];12(6):7580–7587. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5515

- Engel C, Rhiem K, Hahnen E, et al. German consortium for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (GC-HBOC). Prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1/2 germline mutations among 802 women with unilateral triple-negative breast cancer without family cancer history. BMC Cancer. 2018 Mar 7;18(1):265. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4029-y

- Young SR, Pilarski RT, Donenberg T, et al. The prevalence of BRCA1 mutations among young women with triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009 Mar 19;9(1):86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-86

- Millikan RC, Newman B, Tse CK, et al. Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008 May;109(1):123–139. Epub 2007 Jun 20. Erratum in: Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008 May;109(1):141. Dressler, Lynn G [added]. PMID: 17578664; PMCID: PMC2443103. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9632-6

- Kotsopoulos J, Gronwald J, Huzarski T, et al. And the hereditary breast cancer clinical study group. Tamoxifen and the risk of breast cancer in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023 Jul 11;201(2):257–264. doi: 10.1007/s10549-023-06991-3

- Finch AP, Lubinski J, Møller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014 May 20;32(15):1547–1553.

- Brown LC, Salgado R, Luen SJ, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyctes in triple-negative breast cancer: update for 2020. Cancer J. 2021 Jan 1;27(1):25–31. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000501

- Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Aug 1;13(15 Pt 1):4429–4434.

- Giannakeas V, Narod SA. A generalizable relationship between mortality and time-to-death among breast cancer patients can be explained by tumour dormancy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019 Oct;177(3):691–703. Epub 2019 Jul 1. PMID: 31264063; PMCID: PMC6745044. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05334-5

- Popovic LS, Matovina-Brko G, Popovic M, et al. Targeting triple-negative breast cancer: a clinical perspective. Oncol Res. 2023 May 24;31(3):221–238. doi: 10.32604/or.2023.028525

- Guven DC, Yildirim HC, Kus F, et al. Optimal adjuvant treatment strategies for TNBC patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant treatment. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2023 May;31:1–11.

- Morganti S, Bychkovsky BL, Poorvu PD, et al. Adjuvant olaparib for germline BRCA carriers with HER2-negative early breast cancer: evidence and controversies. Oncology. 2023 Jul 5;28(7):565–574. doi: 10.1093/oncolo/oyad123

- Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, et al. KEYNOTE-522 investigators. Event-free survival with pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):556–567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112651

- Dixon-Douglas J, Loibl S, Denkert C, et al. Integrating immunotherapy into the treatment landscape for patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2022 Apr;42(42):1–13. PMID: 35649211. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_351186