ABSTRACT

Hemophilia is a rare bleeding disorder associated with spontaneous and post-traumatic bleeding. Each hemophilia patient requires a personalized approach to episodic or prophylactic treatment, but self-management can be challenging for patients, and avoidable bleeding may occur. Patient-tailored care may provide more effective prevention of bleeding, which in turn, may decrease the likelihood of arthropathy and associated chronic pain, missed time from school or work, and progressive loss of mobility. A strategy is presented here aiming to reduce or eliminate bleeding altogether through a holistic approach based on individual patient characteristics. In an environment of budget constraints, this approach would link procurement to patient outcome, adding incentives for all stakeholders to strive for optimal care and, ultimately, a bleed-free world.

1. Introduction

Hemophilia is a congenital bleeding disorder caused by a clotting factor deficiency that impedes the proper clotting of blood. Because it is a recessive X chromosome disorder, it occurs almost exclusively in males. Hemophilia A (factor VIII, FVIII, deficiency) occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 live births and is about four to five times more common than hemophilia B (factor IX, FIX, deficiency) [Citation1].Footnote1 The clinical phenotype of hemophilia is associated with a residual amount of clotting factor circulating in the blood, with the risk and occurrence of spontaneous bleeding into joints and muscles increasing with factor-deficit severity [Citation2]. Recurrent bleeding into a joint leads to iron deposits in the synovial membrane with progressive destruction of cartilage and the bone surface resulting in crippling arthropathy [Citation3].

Current best practice of care for hemophilia patients is prophylactic treatment with intravenous infusions at regular intervals of FVIII or FIX concentrates, referred to as clotting factor concentrates (CFCs). These CFCs replace deficient blood protein and enable coagulation [Citation4]. Patients currently tend to receive 20–40 IU/kg two to three times per week or every other day on a prophylaxis regimen [Citation2]. The dose may be adjusted based on bleeding response to treatment, leaving the patient at risk of bleeding while dosing is refined; any breakthrough bleeding increases the risk of arthropathy development or other sequelae [Citation5].

Treatment aims to eliminate or at least reduce the number of bleeding events. In doing so, treatment should therefore prevent or delay development of joint damage development and consequent joint function and health-related quality of life impairment [Citation6]. It has been demonstrated that joint damage can occur following even one or two bleeding events [Citation5,Citation7–Citation14]. The ultimate goal can and should be to prevent all joint bleeding [Citation5].

The importance of individualizing care for hemophilia, whether it be ‘on demand’ (episodic treatment for acute bleeding episodes) or prophylaxis, has been much discussed in peer-reviewed literature [Citation15–Citation17]. Personalized care [Citation18,Citation19]of hemophilia patients has been shown not only to improve long-term prognoses of patients and their quality of life, but also to reduce direct costs of treatment and indirect costs to society incurred by work/school absenteeism [Citation20–Citation25]. And yet personalization of treatment has not been widely and fully adopted, perhaps in part because it may not be adequately incentivized for patients, physicians, and payers, and the tools for personalization may not be available to a sufficient extent.

While up to 75% of people with hemophilia worldwide do not have access to adequate therapy [Citation26], the major obstacle to the goal of ‘zero bleeding for all patients’ is represented by tremendous constraints on healthcare expenditure. In fact, cost of care for a single person with hemophilia is one of the highest compared to other rare chronic illnesses. In addition, the increasing lifespan and the introduction of newer, more expensive medications are multiplying the financial burden on all national health systems, regardless of wealth [Citation27]. This is a call for an action to improve standards of care in a sustainable way and for increased discussion about possible paths that might avoid increasing already high treatment costs but still lead to optimal outcomes (e.g. prevention of all bleeding).

Even in the developed world, where bleeding prophylaxis is high standards and completely reimbursed by national health insurance programs, many patients still experience bleeding episodes. In fact, a recent report of the United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors’ Organisation on health status in children and adults with hemophilia showed mean annual bleeding rates of 2.79 and 5.02 in patients (aged <18 years and ≥18 years, respectively) receiving prophylaxis treatment [Citation28]. Even in clinical trials, where compliance is usually very high, 50% of patients have 0 bleeds [Citation29,Citation30].

We have developed an optimized treatment and innovative procurement model in which a budget-linked incentive is given to all stakeholders to improve outcomes while containing costs through innovative, personalized solutions. These require the empowerment of people with hemophilia (PWH) and allow any healthcare system – large or small – to track service impact and success in a transparent way. We believe that this innovative approach will address a substantial unmet need and provide additional value to patients, physicians, healthcare providers, and payers.

2. Optimized treatment and innovative procurement model

With rising demand for CFCs and limited resources, innovative procurement solutions such as those envisioned by the proposed model are needed to maintain and improve access of PWH to care and positive outcomes. An innovative approach should incentivize all hemophilia stakeholders – patients, healthcare professionals (HCPs), and payers – to collaborate in providing a personalized treatment program to achieve the best possible outcome while hindering increases in healthcare expense [Citation31–Citation33].

2.1. Innovative clinical model

Design and implementation of a patient’s treatment plan rest in the hands of the physician entrusted with this responsibility. Physicians usually choose the type of CFC, determine the dose and frequency of administration and provide a prescription to the patient who is then charged with self-administration of the drug. Historically, prophylactic dosing of CFC had been done using the patient’s body weight and a ‘standard amount’ of CFC (based on local guidelines), which was adjusted to the bleeding frequency a posteriori. Recently, increased consideration has been taken regarding: (a) the goals and desires of the individual patient; (b) clinical characteristics such as body mass index, presence of joint damage, level and frequency of physical activity; (c) any mechanical, cognitive and financial limitations that may impact compliance; and (d) the individual pharmacokinetic (PK) profile [Citation16,Citation17,Citation34–Citation42]. An individual patient’s prophylactic dosage and infusion schedule based on their unique PK characteristics are increasingly considered crucial for maintenance of optimal factor plasma levels, in particular during critical times of physical activities, which are associated with higher bleeding risk. Utilization of risk modeling may guide physicians to adjust treatment and improve patient safety during active periods [Citation43].

An efficient dosing program tailored according to patient clinical needs and desires, together with increasing patient empowerment, shared decision making and self-management [Citation44,Citation45], are likely to minimize bleeding events and their complications without uncontrolled increases in healthcare costs. In contrast to ‘individualized’ prophylaxis [Citation16,Citation17,Citation19,Citation39,Citation46,Citation47], which has already represented an improvement over standard ‘one size fits all’ dosing, ‘patient-centric prophylaxis’ integrates patient outcomes and provides the opportunity to flexibly tailor the therapy on an ongoing basis through patient self-management. Personalized plans [Citation47] of care must take into consideration, among other variables, the patient’s lifestyle; type, intensity, and frequency of physical activity and associated bleeding risks; the psychosocial environment and support network of patient and family as well as the financial resources available [Citation39]. Moreover, it is crucial that detailed information is provided by the patient and is managed by both patient and healthcare provider.

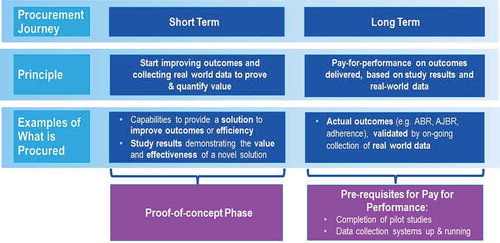

For example, many patients who bleed frequently despite remaining adherent to the prescribed infusion plan – so-called ‘high bleeders’ – may be prescribed inadequate doses of CFC or at infusion intervals beyond the duration, which afford protection from bleeding [Citation48]. Others who rarely bleed, ‘low bleeders,’ may receive doses of CFC that are greater than they might really require (). The right balance can only be determined through careful, real-time monitoring of patients, tracking bleeding events and infusions of CFC, together with an accurate PK profile. In fact, understanding at what factor level the patient bled would assist the physician and could therefore drive dosage, intervals, and timing of infusions. Treatment monitoring, on an individual basis by caregivers, patients and their physicians, and on a larger scale by payers and healthcare providers, and consequent dosing can improve the safety, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of hemophilia care [Citation9,Citation49–Citation52]. Resource reallocation may be possible between patients, facilitating investment by healthcare providers and payers into services and programs to improve patient outcomes.

Figure 1. Examples of personalized care and integrated services of an innovative outcome-based care and procurement model. The goal of the Innovative Outcome-based Care and Procurement Model is to efficiently provide clotting factors to people with hemophilia. Here we list potential supportive tools for physicians and patients grouped according to trough levels and bleeding frequency to reduce or eliminate bleeds.

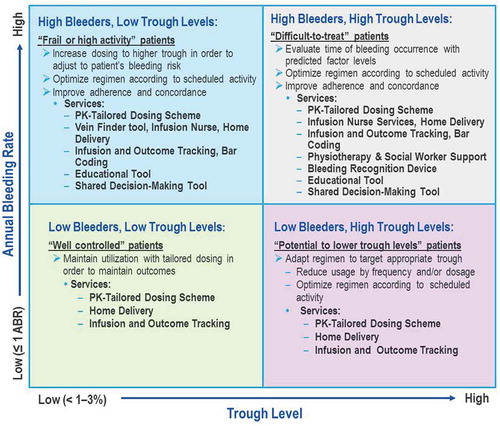

Close, flexible disease management will require accurate real-time data tracking to help treating physicians and patients to monitor effectiveness of therapeutic strategies and health-related factor consumption and to provide regular benchmarking (). Personalized patient management tools will contribute to maintaining an accurate recording of bleeding episodes, factor infusions, and other life events that might impact care and outcome.

Figure 2. Innovative outcome based care and procurement: the ins and outs. This model is facilitated through the integration of real-world data collection, tailored care and patient empowerment into personalized care. Outcome-based care thereby produces an opportunity for innovative procurement and improved outcomes, which result in increased value for money.

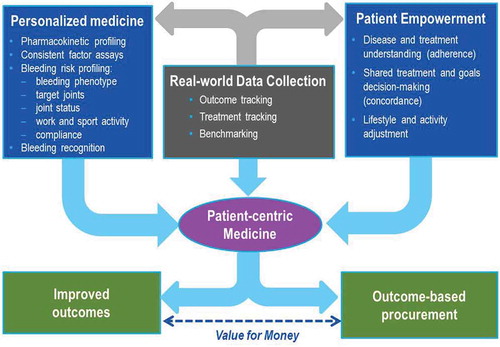

A second variable to be considered is compliance with the prescribed infusion schedule and an examination of the factors leading to a lack thereof. Self-management of disease can be challenging for patients, in particular for adolescents and young adults [Citation53]. Compliance can be the result of understanding of the disease and the treatment (referred to as adherence) and can influence participation in disease management and decision-making (referred to as concordance). Consequently, inadequate degrees of adherence and concordance can result in higher bleeding rates [Citation54,Citation55]. Adolescents have 20–30% lower compliance than infants (aged <2 years) and adults (aged >25 years), and 2.5 times higher rates of bleeding events [Citation56–Citation58]. Therefore, an innovative approach to care aimed at improving compliance can have important effects on treatment outcomes [Citation29] and represents a considerable achievement for all hemophilia stakeholders. Improved compliance can be achieved by empowering the patient with the right tools, knowledge, and targeted assistance to support self-management of his/her disease (see ) [Citation59]. Concordance between patient and physician is key to optimizing outcomes. Shared decision-making tools can facilitate this process and allow physicians to determine treatment schedules together with patients to fit their individual needs.

Figure 3. Self management and adherence: crucial for optimized outcomes: non-adherence in chronic disease is estimated to cost $100 billion per year in the US, or 4.5% of total healthcare spending,3 due to avoidable hospitalization costs alone. Total cost of non-adherence to the system is the probably much greater. Sources: aLorig and Holman, 2003; bSchrijvers, et al. 2013; cZappa et al., 2012; dClinical trial: ‘Nurse facilitated adherence therapy for haemophilia’, 2014. 3New England Healthcare Institute. ‘Thinking Outside the Pillbox: A Systemwide Approach to Improving Patient Medication Adherence for Chronic Disease’. A NEHI Research Brief. August 2009.

2.2. Innovative outcome-based care and procurement model

The major obstacle to the goal of eliminating bleeding with CFC replacement is cost [Citation27]. For the treatment of rare diseases, in particular, the balance of effectiveness and cost remains a significant issue. In order to save costs, today healthcare systems rely on procurement systems based on price per unit and volume discounts (the more is purchased the lower the price per unit) [Citation60]. Such a strategy, while it can save money, is not intended to create incentives for improved levels of care. Indeed, as innovative clotting factors continue to enter the marketplace, a new approach to procurement might allow relative estimation of their value in terms of outcome improvement and not simply the yearly consumption in units or milligrams. In addition, inadequate attention to outcomes on a system-wide level can translate into increased CFC factor used without corresponding improved outcomes, in addition to economic losses due to reduced productivity to society (including work/school days lost) and increased healthcare expenditures. One example of an added healthcare expenditure could be joint replacement in order to deal with morbidities incurred after bleeding episodes.

An essential element of this model for treatment optimization is transparency of individual patient data, such as bleeding and infusion records from which CFC utilization can be imputed. In fact, in order to personalize treatments and improve patient’s health and well-being [Citation36,Citation38,Citation61–Citation65], HCPs need accurate data from their patients as do healthcare providers and payers in order to monitor utilization and forecast future needs. As an example, the identification of treatment ‘outliers’ using a tracking system could empower all stakeholders (patients, HCPs, healthcare providers, and payers) to seek causes and consequently solutions. Unfortunately, patients often do not track bleeding or treatment information in a consistent and reliable way. There is a great need for a fast, easy-to-use system for patients to report accurate data, enabling stakeholders to recognize trends and deviations in a timely fashion in order to intervene. Such a tracking system should be transparent and visible to all stakeholders to be of benefit. It is therefore important to collect outcome and consumption data in order to have a precise notion of the situation, to set goals for the future, to link these goals to procurement, and to facilitate benchmarking between centers and countries. These support a comprehensive tailored care model in which a team of medical, surgical, dental, nursing, physical therapy, and psychosocial experts collaborate in the planning and administration of care for PWH. Even though this information is currently already collected to some extent, completeness of this data collection is insufficient, particularly for the goals mentioned.

The lack of availability of reliable data at treatment centers, both small and large, regarding issues, such as bleeding frequency, site of bleeding, compliance levels, activity levels, joint status, quality of life, personalized goal achievement, etc., creates problems for practitioners and patients in managing the disease. However, it also imposes a barrier to health systems and payers, which need to record and justify drivers of treatment costs, and thereby to control costs and predict future procurement needs [Citation66–Citation68]. Accurate, real-time, patient-level cumulative data also facilitates benchmarking within a single patient over time and among patients, facilitating comparisons of outcomes between different geographies, hemophilia care centers, treatment regimens, or physician practices [Citation69]. Nevertheless, utilization patterns and outcomes may vary over time in ways that often cannot be predicted or explained, making cost predictability and budget forecasting difficult. Large prospective cohort studies can help to increase transparency and enable benchmarking between centers and regions [Citation70–Citation73].

The costs of data collection should be associated with the outcome-based procurement offering. Due to the importance of this undertaking, all stakeholders should be involved (patients, physicians, and payers). If possible, data should be analyzed by an independent party, since its results may impact the purchasing mechanisms.

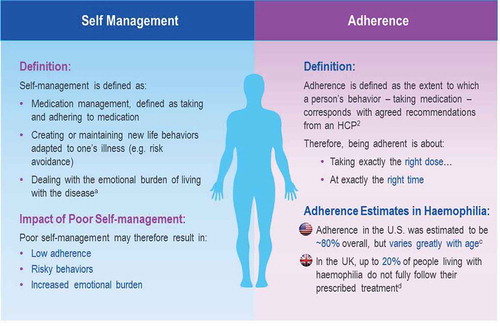

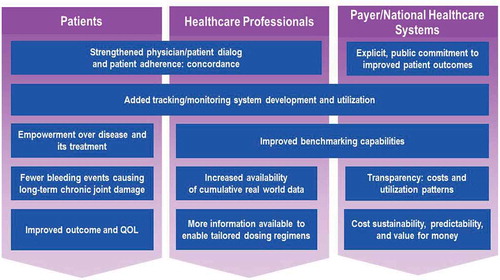

A procurement framework based on outcomes that are agreed on by stakeholders, rather than the traditional price per unit [Citation70], and strives to align stakeholders’ incentives toward a common goal of effective and efficient treatment of the disease would be of benefit to all hemophilia stakeholders (). The empowerment of PWH to self-manage their disease through positive health-related behaviors will enable physicians to accurately prescribe optimal doses of CFC using safe and cost-effective personalized regimens. The collection of real-world outcomes and utilization data from individual patients and their HCPs would facilitate cost predictability. Accurate cumulative data on populations would also provide payers with deeper insight into resource usage, real-world effectiveness, and best practice patterns across healthcare providers, hemophilia centers, regions, patient characteristics, etc [Citation71].

Figure 4. Innovative outcome-based care and procurement model stakeholder benefits. By aligning the goals of all stakeholders involved with hemophilia treatment to improve outcomes, the innovative outcome-based care and procurement model should provide significant benefits. The foundation for these benefits would begin with increased motivation to partake in increased concordance between patient and physician, built upon by improved tracking and monitoring systems to provide individual treatment plan comparability as well as increased cumulative benchmarking data. In addition, by supporting such a procurement policy, the payer demonstrates his/her commitment to the improvement of patient outcomes.

One similarly conceived program was instituted in North Carolina in 2008, coordinated by university-affiliated pharmacists and hematologists to monitor and improve treatment programs of local PWH through staff education and product/dose/infusion frequency adjustments. This program achieved an estimated annual $4 million in cost savings and a reduction in re-admissions due to bleeding episodes – despite a 22% increase in the volume of patients treated in the fiscal year 2013 compared to the previous year.

3. Potential mechanisms for introduction of an outcome-based care and procurement program

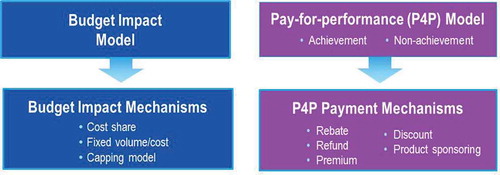

shows an overview of two potential innovative procurement models. The first, the budget impact model, could be used as a ‘proof of concept’ phase, preceding a ‘pay-for-performance’-like model. Three budget impact mechanisms allow the payer to safely test the model without exposure to investment risk or demand limitation: first the cost-share mechanism, by which the payer is open to cost sharing between the payer and the manufacturers of clotting factors; second, the fixed volume/cost mechanism, in which the payer seeks budget neutrality and predictability by acquiring increased amounts of data on CFC utilization; and third, the capping model mechanism, which allows the payer to seek budget savings and cost predictability by placing a cap on the amount of CFC it will purchase based on a fixed outcome response.

Figure 5. Overview of potential innovative outcome-based care and procurement financial models. Below are two potential versions of financing Innovative Outcome-Based Care and Procurement and their mechanisms.

The ‘pay-for-performance’ model reflects achievement or non-achievement of outcome guarantees and their associated payment flows. Baseline values and real world evidence are prerequisites for the performance of these outcome indicators. Indicators of outcome achievement, among others, might include: annual joint bleeding rates, degree of adherence, health-related quality of life scores, pain scale, number of sick days, number of new target joints, joint status scale, goal attainment scale, patient activation measure. Single indicators, multiple indicators, or a composite scale could be used to measure achievement. Cohorts of age, severity, geography, and/or treatment type can be defined within populations for the purpose of measuring achievement of outcomes. The payment mechanisms might include rebates, discounts, or premium offerings in the case of improved treatment outcomes.

These models are just examples of how outcome indicators could be used to determine cost in the provision of CFCs to hemophilia patients. Numerous other options should be considered. The authors welcome any and all discussion within the hemophilia community of how outcomes can be optimized, and incentives for all to improve the standard of care, while maintaining or reducing costs. An example of how the outlook for the future might look were this procurement model adopted is represented by : a future with lower bleeding rates directly enabled by the application of data and benchmarking. In essence, this model integrates evidence-based medicine into a procurement schema.

4. Expert commentary

Recent improvements in the treatment of hemophilia patients have brought prevention of all bleeding events and their major complications potentially within reach [Citation23,Citation74]. The main obstacle is represented by the high cost of care. Achieving the goal of a functional cure requires personalized, outcome-based, multidisciplinary care to maximize prophylactic effectiveness without increasing overall healthcare costs. Even if resource utilization increases, such potential increases can be controlled by rebate mechanisms based on better outcomes.

Individualized dosing requires pharmacokinetic profiling of each patient using reliable and accurate assays to measure the plasma FVIII or IX concentration, careful dose calculation in which all available information regarding the patient is incorporated, and a wide range of CFC potencies with user-friendly infusion devices available in order to arrive at the precise dose for the patient [Citation23,Citation29,Citation32,Citation35,Citation75,Citation76]. Consideration of the potential barriers to adherence must be addressed. Individuals with difficult to access veins may be offered services and devices to assist with infusions (such as vein scanners) and/or products with extended half-life. Moreover, therapy plans must be adapted to individuals’ changing needs [Citation26,Citation47]. A high level of engagement in the decision-making process and awareness of the options on the part of the patient and his caregivers facilitates his ownership of the disease, giving a sense of personal satisfaction when outcomes improve due to changes in his health-related behaviors.

An innovative framework that includes patient-centric care with tailored treatment and a new model for procurement can make this possible. Rising healthcare costs would be addressed by fighting poor compliance due to inconsistent adherence and scarce concordance and inadequate transparency in record keeping and benchmarking abilities. The goal of improvement of outcomes and provision of ‘value for money’ through patient-centric care, services and programs, together with personalized dosing that accommodates the specific needs of individual patients, patient empowerment, and real-world data collection, could be realized. This requires a procurement approach shifting from volume-based price-per-unit to performance-based care fees.

All stakeholders – patients, caregivers, HCPs, healthcare providers, payers, policy-makers, and manufacturers – are called on to support this tectonic shift in the procurement paradigm and bring the treatment of people with hemophilia up to a new level of optimal care.

5. Five-year view

Provision of care is evolving from ‘empirical medicine’, where diagnosis was built on pattern of signs and symptoms, therapy was focused on standard protocols, outcomes were predicted based on probabilities, and care was charged on a fee-for-drug basis, toward ‘precision medicine’, where disease causes are fully understood, diagnoses precisely made, therapies are patient-based and are charged on a fee-for-outcome basis. This approach will also apply to hemophilia care, thanks to improvement of diagnostic tools and particularly due to: (a) early recognition of bleeding complications (e.g. clinical and molecular imaging), (b) increasing research on biomarkers and genetic blueprints that can better define or even predict patient bleeding and arthropathy phenotypes, (c) availability of tools for user-friendly early detection of bleeding (e.g. hand-held ultrasound scanners), and (d) methods for estimating of individual PK response.

Case by case, country by country, the procurement model should be discussed by all stakeholders. We suggest that procurement models be based on an outcome-based approach to care and to procurement [Citation77]. These new procurement models have already been proposed, particularly in oncology [Citation78], to promote precision medicine: the right product for the right patient at the right time. Other varieties of pay for performance models for physician or hospital compensation have long been common in healthcare systems [Citation79,Citation80].

These movements will allow more precise individual treatment that can successfully realize the prevention of bleeding episodes in all patients with hemophilia, and consequently prevent all complications associated with bleeding and provide a ‘functional cure’ until a ‘genetic cure’ becomes available. To achieve this goal in an environment of increasing budget constraints, we should start a journey from a procurement method based on price per volume of replacement therapy products to a performance-based procurement system where financial incentives are linked to a holistic care approach positioned to achieve agreed outcome targets. As pilot programs are developed utilizing this new procurement method, the authors expect that evidence will be gathered proving that outcomes improve.

6. Key issues

Prevention of bleeding is the mainstay of treatment for people with hemophilia. Prevention of all bleeds is within reach.

Cost of hemophilia care per patient is one of the highest and it is lifelong for all patients. Any further investment is unaffordable by the great majority of national health systems.

An innovative model aimed to improve standards of care requires personalized, outcome-based, multidisciplinary care to maximize prophylactic effectiveness without increasing overall healthcare costs.

Such a model would require a patient-centric approach that takes into account the individual PK profile, clinical status, psychosocial conditions, personal needs and desires.

To improve outcomes, promotion of education and patients’ empowerment is needed and requires appropriate tools and activities.

The proposed innovative model requires data collection tools that can help collect actionable insights, enabling tracking of outcome and health resources consumption, and enabling benchmarking to optimize care.

This model prioritizes procurement based on patient outcomes to deliver the best value for money.

The payment mechanisms might include rebates, discounts, or premium offerings in the case of improved treatment outcomes.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

All authors are full-time employees of Baxalta US Inc/Baxalta Innovations GmbH. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Roman Irsiegler for his critical review of the manuscript.

Notes

1. https://www.hemophilia.org/Bleeding-Disorders/Types-of-Bleeding-Disorders/Retrieved 31 Nov 2015

References

- Mannucci PM, Tuddenham EGD. The hemophilias: progress and problems. Semin Hematol. 1999;36:104–117.

- Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2013;19:e1–e47.

- Valentino LA. Blood-induced joint disease: the pathophysiology of hemophilic arthropathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1895–1902.

- Oldenburg J. Optimal treatment strategies for hemophilia: achievements and limitations of current prophylactic regimens. Blood. 2015;125:2038–2044.

- Gringeri A, Ewenstein B, Reininger A. The burden of bleeding in haemophilia: is one bleed too many? Haemophilia. 2014;20:459–463.

- Nijdam A, Kurnik K, Liesner R, et al. How to achieve full prophylaxis in young boys with severe haemophilia A: different regimens and their effect on early bleeding and venous access. Haemophilia. 2015;21:444–450.

- Nilsson IM, Berntorp E, Lofqvist T, et al. Twenty-five years’ experience of prophylactic treatment in severe haemophilia A and B. J Intern Med. 1992;232:25–32.

- Funk MB, Schmidt H, Becker S, et al. Modified magnetic resonance imaging score compared with orthopaedic and radiological scores for the evaluation of haemophilic arthropathy. Haemophilia. 2002;8:98–103.

- Fischer K. Prophylaxis for adults with haemophilia: one size does not fit all. Blood Transfus. 2012;10:169–173.

- Fischer K, Astermark J, van der Bom JG, et al. Prophylactic treatment for severe haemophilia: comparison of an intermediate-dose to a high-dose regimen. Haemophilia. 2002;8:753–760.

- Manco-Johnson MJ, Abshire TC, Shapiro AD, et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:535–544.

- Kraft J, Blanchette V, Babyn P, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and joint outcomes in boys with severe hemophilia a treated with tailored primary prophylaxis in Canada. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:2494–2502.

- Funk M, Schmidt H, Escuriola-Ettingshausen C, et al. Radiological and orthopedic score in pediatric hemophilic patients with early and late prophylaxis. Ann Hematol. 1998;77:171–174.

- den Uijl IEM, de Schepper AMA, Camerlinck M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in teenagers and young adults with limited haemophilic arthropathy: baseline results from a prospective study. Haemophilia. 2011;17:926–930.

- Sørensen B, Auerswald G, Benson G, et al. Rationale for individualizing haemophilia care. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015;26:849–857.

- Ar MC, Vaide I, Berntorp E, et al. Methods for individualising factor VIII dosing in prophylaxis. Eur J Haematol. 2014;93(Suppl 76):16–20.

- Valentino LA. Considerations in individualizing prophylaxis in patients with haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2014;20:607–615.

- McCarthy M. Obama seeks $213m to fund “precision medicine”. BMJ. 2015;350:h587.

- Awad AG. ‘The patient’: at the center of patient-reported outcomes. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15:729–731.

- Earnshaw SR, Graham CN, McDade CL, et al. Factor VIII alloantibody inhibitors: cost analysis of immune tolerance induction vs. prophylaxis and on-demand with bypass treatment. Haemophilia. 2015;21:310–319.

- Escobar MA. Health economics in haemophilia: a review from the clinician’s perspective. Haemophilia. 2010;16(Suppl 3):29–34.

- Risebrough N, Oh P, Blanchette V, et al. Cost-utility analysis of Canadian tailored prophylaxis, primary prophylaxis and on-demand therapy in young children with severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2008 Jul;14(4):743–752.

- Farrugia A, Cassar J, Kimber MC, et al. Treatment for life for severe haemophilia A- A cost-utility model for prophylaxis vs. on-demand treatment. Haemophilia. 2013;19:e228–e238.

- Neufeld EJ, Recht M, Sabio H, et al. Effect of acute bleeding on daily quality of life assessments in patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors and their families: observations from the dosing observational study in hemophilia. Value Health. 2012;15:916–925.

- Valente M, Cortesi PA, Lassandro G, et al. Health economic models in hemophilia A and utility assumptions from a clinician’s perspective. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1826–1831.

- Skinner MW. WFH: closing the global gap - achieving optimal care. Haemophilia. 2012;18(Suppl 4):1–12.

- Unim B, Veneziano MA, Boccia A, et al. Pharmacoeconomic review of prophylaxis treatment versus on-demand. ScientificWorldJournal. 2015;2015:596164.

- United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Director’s Organisation. Bleeding disorder statistics for April 2011 to March 2012: a report from the Natinal Haemohilia Database. Vol. 87. United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Director’s Organisation (UKHCDO); 2012. Available from: http://www.ukhcdo.org/docs/AnnualReports/2012/1UK%20National%20Haemophilia%20Database%20Bleeding%20Disorder%20Statistics%202011-2012%20for%20website.pdf

- Valentino LA, Mamonov V, Hellmann A, et al. A randomized comparison of two prophylaxis regimens and a paired comparison of on-demand and prophylaxis treatments in hemophilia A management. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:359–367.

- Manco-Johnson MJ, Kempton CL, Reding MT, et al. Randomized, controlled, parallel-group trial of routine prophylaxis versus on-demand treatment with rFVIII-FS in adults with severe hemophilia A (SPINART). J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1119–1127.

- Schneider U. Double moral hazard and outcome-based remuneration of physicians. Working Paper 022. Bavarian Graduate Program in Econmoics (BGPE); 2007. Available from: http://www.bgpe.de/texte/DP/022_schneider.pdf

- Carlsson M, Berntorp E, Björkman S, et al. Improved cost-effectiveness by pharmacokinetic dosing of factor VIII in prophylactic treatment of haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 1997;3:96–101.

- Brown SA, Phillips J, Barnes C, et al. Challenges in haemophilia care in Australia and New Zealand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:1985–1991.

- Antunes SV, Tangada S, Phillips J, et al. Comparison of historic on-demand and prophylaxis bleeding episodes in hemophilia A and B patients with inhibitors treated with FEIBA NF. Haemophilia. 2014;20(Suppl 3):96.

- Berntorp E, Spotts G, Patrone L, et al. Advancing personalized care in hemophilia A: ten years’ experience with an advanced category antihemophilic factor prepared using a plasma/albumin-free method. Biologics. 2014;2014:115–127.

- Pollmann H, Klamroth R, Vidovic N, et al. Prophylaxis and quality of life in patients with hemophilia A during routine treatment with ADVATE [antihemophilic factor (recombinant), plasma/albumin-free method] in Germany: a subgroup analysis of the ADVATE PASS post-approval, non-interventional study. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:689–698.

- Khawaji M, Astermark J, Berntorp E. Lifelong prophylaxis in a large cohort of adult patients with severe haemophilia: a beneficial effect on orthopaedic outcome and quality of life. Eur J Haematol. 2012;88:329–335.

- Gringeri A, Lundin B, Von Mackensen S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of prophylaxis in children with hemophilia A (the ESPRIT Study). J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:700–710.

- Petrini P, Valentino LA, Gringeri A, et al. Individualizing prophylaxis in hemophilia: a review. Expert Rev Hematol. 2015;8:237–246.

- Ahnström J, Berntorp E, Lindvall K, et al. A 6-year follow-up of dosing, coagulation factor levels and bleedings in relation to joint status in the prophylactic treatment of haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2004;10:689–697.

- Fernandes S, Carvalho M, Lopes M, et al. Impact of an individualized prophylaxis approach on young adults with severe hemophilia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40:785–789.

- Abshire T. An approach to target joint bleeding in hemophilia: prophylaxis for all or individualized treatment? J Pediatr. 2004;145:581–583.

- Broderick CR, Herbert RD, Latimer J, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of bleeding in children with hemophilia. JAMA. 2012;308:1452–1459.

- O’Mahony B, Kent A, Ayme S. Pfizer-sponsored satellite symposium at the European Haemophilia Consortium (EHC) congress: changing the policy landscape: haemophilia patient involvement in healthcare decision-making Pfizer-sponsored satellite symposium at the European Haemophilia Consortium (EHC) congress: changing the policy landscape: haemophilia patient involvement in healthcare decision-making. Eur J Haematol. 2014;92(Suppl 74):1–8.

- Croteau SE, Padula M, Quint K, et al. Center-based quality initiative targets youth preparedness for medical independence: HEMO-milestones tool in a comprehensive hemophilia clinic setting. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016 Mar;63(3):499–503.

- Reininger AJ, Chehadeh HE. The principles of PK-tailored prophylaxis. Hamostaseologie. 2013;33(Suppl 1):S32–S35.

- Collins PW. Personalized prophylaxis. Haemophilia. 2012;18(Suppl 4):131–135.

- Collins PW, Björkman S, Fischer K, et al. Factor VIII requirement to maintain a target plasma level in the prophylactic treatment of severe haemophilia A: influences of variance in pharmacokinetics and treatment regimens. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:269–275.

- Miners AH. Economic evaluations of prophylaxis with clotting factor for people with severe haemophilia: why do the results vary so much? Haemophilia. 2013;19:174–180.

- Coppola A, Morfini M, Cimino E, et al. Current and evolving features in the clinical management of haemophilia. Blood Transfus. 2014;12(Suppl 3):S554–S562.

- Iem DU, Fischer K, Halimeh S, et al. Including the life-time cumulative number of joint bleeds in the definition of primary prophylaxis. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:965–968.

- Gringeri A, Cortesi P, Iannazzo S, et al. PK-driven prophylaxis using MyPKFiT vs. standard prophylaxis in haemophilia A: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Poster: presented at (EAHAD); 2016 February 3–5; Malmö, Sweden.

- Geraghty S, Dunkley T, Harrington C, et al. Practice patterns in haemophilia A therapy – global progress towards optimal care. Haemophilia. 2006;12:75–81.

- Duncan NA, Kronenberger WG, Krishnan S, et al. Adherence to prophylactic treatment in hemophilia as measured using thre VERITAS-Pro and annual bleed rate (ABR). Value Health. 2014;17(3):A230.

- Collins PW, Blanchette VS, Fischer K, et al. Break-through bleeding in relation to predicted factor VIII levels in patients receiving prophylactic treatment for severe haemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:413–420.

- Petrini P, Seuser A. Haemophilia care in adolescents–compliance and lifestyle issues. Haemophilia. 2009;15(Suppl 1):15–19.

- Zappa S, McDaniel M, Marandola J, et al. Treatment trends for haemophilia A and haemophilia B in the United States: results from the 2010 practice patterns survey. Haemophilia. 2012;18:e140–e153.

- Quon D, Reding M, Guelcher C, et al. Unmet needs in the transition to adulthood: 18- to 30-year-old people with hemophilia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(Suppl 2):S17–S22.

- O’Mahony B, Skinner MW, Noone D, et al. Assessments of outcome in haemophilia - a patient perspective. Haemophilia. 2016 Mar 14. doi:10.1111/hae.12922. [Epub ahead of print]

- Hay CRM. Purchasing factor concentrates in the 21st century through competitive tendering. Haemophilia. 2013;19:660–667.

- Oldenburg J, Kurnik K, Huth-Kuhne A, et al. AHEAD. Advate in HaEmophilia A outcome database. Hamostaseologie. 2010;30:S23–S25.

- Iorio A, Marcucci M, Cheng J, et al. Patient data meta-analysis of Post-Authorization Safety Surveillance (PASS) studies of haemophilia A patients treated with rAHF-PFM. Haemophilia. 2014;20:777–783.

- Klamroth R, Pollmann H, Hermans C, et al. The relative burden of haemophilia A and the impact of target joint development on health-related quality of life: results from the ADVATE Post-Authorization Safety Surveillance (PASS) study. Haemophilia. 2011;17:412–421.

- Richards M, Altisent C, Batorova A, et al. Should prophylaxis be used in adolescent and adult patients with severe haemophilia? An European survey of practice and outcome data. Haemophilia. 2007;13:473–479.

- Collins PW, Fischer K, Morfini M, et al. Implications of coagulation factor VIII and IX pharmacokinetics in the prophylactic treatment of haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2011;17:2–10.

- Feldman BM, Berger K, Bohn R, et al. Haemophilia prophylaxis: how can we justify the costs? Haemophilia. 2012;18:680–684.

- Fischer K, Pouw ME, Lewandowski D, et al. A modeling approach to evaluate long-term outcome of prophylactic and on demand treatment strategies for severe hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2011;96:738–743.

- De Moerloose P, Arnberg D, O’Mahony B, et al. Improving haemophilia patient care through sharing best practice. Eur J Haematol. 2015;95(Suppl 79):1–8.

- Nijdam A, Bladen M, Hubert N, et al. Using routine haemophilia joint health score for international comparisons of haemophilia outcome: standardization is needed. Haemophilia. 2016;22(1):142–147. doi:10.1111/hae.12755.

- Kesselheim AS, Gagne JJ. Strategies for postmarketing surveillance of drugs for rare diseases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95:265–268.

- Amerine LB, Chen SL, Daniels R, et al. Impact of an innovative blood factor stewardship program on drug expense and patient care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015 Sep 15;72(18):1579–1584.

- Concato J, Lawler EV, Lew RA, et al. Observational methods in comparative effectiveness research. Am J Med. 2010;123:e16–e23.

- Lassila R, Rothschild C, De Moerloose P, et al. The European haemophilia therapy standardisation board. Recommendations for postmarketing surveillance studies in haemophilia and other bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2005;11:353–359.

- Darby SC, Kan SW, Spooner RJ, et al. Mortality rates, life expectancy, and causes of death in people with hemophilia A or B in the United Kingdom who were not infected with HIV. Blood. 2007;110:815–825.

- Mingot-Castellano ME, González-Diaz L, Tamayo-Bermejo R, et al. Adult severe haemophilia A patients under long-term prophylaxis with factor VIII in routine clinical practice. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015 Jul;26(5):509–514.

- Björkman S, Blanchette VS, Fischer K, et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics of plasma- and albumin-free recombinant factor VIII in children and adults: the influence of blood sampling schedule on observed age-related differences and implications for dose tailoring. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:730–736.

- Burock S, Meunier F, Lacombe D. How can innovative forms of clinical research contribute to deliver affordable cancer care in an evolving health care environment? Eur J Cancer. 2013 Sep;49(13):2777–2783.

- Health Affairs Blog. 2015. [cited 2016 Apr 11]. Available from: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/04/28/its-time-for-value-based-payment-in-oncology/.

- Bardach NS, Wang JJ, De Leon SF, et al. Effect of pay-for-performance incentives on quality of care in small practices with electronic health records: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(10):1051–1059.

- Jha AK, Joynt KE, Orav JE, et al. The long-term effect of premier pay for performance on patient outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2012 Apr 26;366:1606–1615.