1. Introduction

The Italian National Health Service (INHS) is a three-tiered (central–regional–local), highly decentralized public service, mainly funded by general taxation, which provides universal and comprehensive health care coverage throughout the country, including pharmaceuticals [Citation1]. Once they have satisfied national regulations, the 19 Italian regions and 2 autonomous provinces (all governed by elected politicians) can autonomously manage and control the services delivered by their hospital trusts and local health authorities.

Reimbursable drugs fall into two different classes in Italy: (i) Class A, drugs for severe and chronic diseases; (ii) Class H, drugs dispensed only in the hospital setting. Dispensing reimbursable drugs of Class A through pharmacies is historically remunerated by the INHS on the basis of a fixed margin (30.35%) of the public price [Citation2], corrected by a regressive discount by drug price band and pharmacy turnover since 1997, with a further overall discount (1.83%) since 2010. Obviously, dispensing Class H reimbursable drugs does not involve any distribution margin as these drugs are directly purchased and delivered by health authorities.

From about a decade now, regions [Citation3] can also opt for special delivery for a specific subclass of drugs listed in Class A, those in the so-called ‘Hospital-Territory Formulary’ (PHT, Prontuario Ospedale-Territorio). According to the Italian medicines agency, AIFA (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco), ‘the PHT should guarantee therapeutic continuity between intensive therapies in hospital (Class H) and chronic/short-term therapies in the community (Class A)’. In practice, these drugs can be dispensed to patients either by hospitals (like Class H) or by community pharmacies (like the whole of Class A) through what is termed ‘distribution on behalf’ (DPC, Distribuzione Per Conto). In both cases, medicines are purchased directly by health authorities, but in DPC they are still delivered by community pharmacies according to specific contracts signed with regions by their local associations.

Here, we analyze the general PHT experience in the last decade, and particularly that of DPC, critically discussing its strengths and weaknesses.

2. Analysis

Once the reimbursement of a drug in Class A has been approved, AIFA decides whether to include it or not in the national PHT. Every region can modify this list (and at local level too) and decide whether or not to dispense all the medicines included in PHT through DPC. In practice, every region has to update the national PHT on its own since (surprisingly) AIFA does not publish it on the website, differently from Class A, Class H and other national lists (e.g. the ‘transparency list’ for off-patent drugs).

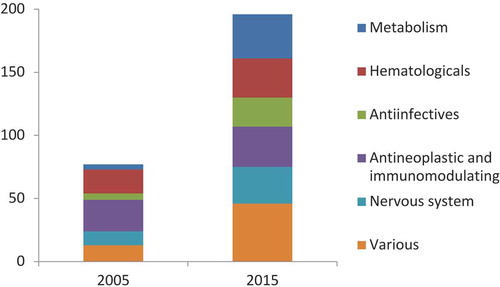

The number of substances listed in the national PHT has more than doubled in the period 2005–2015 (from 11% to 25% of the total actives in Class A) and their ‘mix’ per therapeutic group has also changed a lot (), particularly after the inclusion in 2010 of 40 drugs previously listed in Class H [Citation4]. Currently, only three regions (Val d’Aosta, Calabria, Liguria) and the autonomous province of Trento adopt the National PHT without any local adaptation [Citation5].

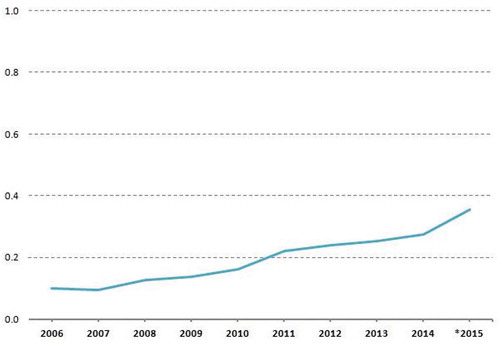

PHT expenditure has continuously grown steeply since its introduction [Citation6], peaking in 2015 at more than half the net public pharmaceutical expenditure through pharmacies for the remaining products in Class A (). This increase stems from the growth of both the proportion of drugs listed in PHT and their average prices. For instance, in Trento the average cost per package in 2015 was €49.72 in DPC, but only €11.12 for the remaining actives in Class A delivered through community pharmacies [Citation7]. Currently, all regions but one (Abruzzo) have opted for DPC as a potential distribution channel. A dispensing fee for each package (ranging from €3.88 in Emilia-Romagna to €11.60 in Molise) is usually agreed to remunerate pharmacies, except in three regions (Latium, Lombardy, and Sardinia) where distribution margins are still more or less proportional to the drug price (i.e. fees increasing with price band). Since health authorities purchase drugs directly and the costs of DPC margins are posted as general services (and not as public pharmaceutical expenditure), in practice, this information is not available at national and regional level. This accounting procedure also excludes these expenses from the calculation of paybacks in case of regional deficits on Class A ceilings.

3. Policy implications

To our knowledge, Italy is the only European Union (EU) country that has a ‘dual channel’ distribution system (pharmacies and hospitals) for a subset of reimbursable drugs and a ‘double fee’ is paid for the same channel (pharmacy). Although AIFA denied that the PHT was introduced for cost containment [Citation3], it is hard to find any other plausible justification, even more so after a decade during which the number of drugs listed has more than doubled in PHT and all the ‘new entries’ have been highly priced.

A still open issue in Italy (like in other continental European countries) is that the INHS remunerates community pharmacies mainly through a (still high) proportion of prices to the public for Class A reimbursable drugs [Citation8]. A more concrete option to contain public pharmaceutical expenditure would have been to replace the present margin with a fixed fee for service unrelated to the public price, as has often been debated unsuccessfully in Italy. For example, in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, distribution margins on reimbursable drugs are much lower and mainly consist of a ‘flat charge’, leaving additional income for pharmacies up to commercial negotiation with wholesalers and/or pharmaceutical companies [Citation2]. Commercially, a distribution margin related to price can be justified only if there are substantial stock costs, which is hardly the case for reimbursable drugs in Italy, which are delivered daily throughout the country. More in general, the marketing advantage given to pharmacies of a monopoly on dispensing reimbursable drugs and thus attracting potential customers to purchase other products should have the payment of low-dispensing fees as a ‘trade-off’ for third-party payers.

The introduction of DPC 10 years ago (together with the PHT) seems to have been a sort of ‘Trojan horse’ to change the actual margin in practice, while formally leaving the historical one. However, the present situation has become very uneven throughout the country since every region has tried different ways to manage it and the PHT list can vary substantially from one region to another, like the DPC margin, partly depending on the influence of local pharmacy associations. The wide range of ‘fees for service’ and the ‘borderline’ examples of Latium (Rome is the capital) and Lombardy (Milan, capital) – two big regions where the DPC margin is illogically related to prices although the INHS is the drug ‘purchaser’ – are likely to reflect the different ‘bargaining power’ of pharmacists at regional level rather than geographical differences. Besides, this regional ‘heterogeneity’ makes the accountancy of public pharmaceutical expenditure difficult at national level too, where the expenses due to DPC margins are not included and thus virtually ‘exempted’ from potential paybacks in case of deficits.

In conclusion, we wonder whether it is perhaps high time to radically change the traditional distribution margin of community pharmacies. This would facilitate the control of public pharmaceutical expenditure and undermine its full dependence on increasing prices.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- Garattini L, Van de Vooren K, Curto A. Regional HTA in Italy: promising or confusing? Health Policy. 2012;108(2–3):203–206.

- Garattini L, Motterlini N, Cornago D. Prices and distribution margins of in-patent drugs in pharmacy: a comparison in seven European countries. Health Policy. 2008;85(3):305–313.

- AIFA. PHT – Prontuario della distribuzione diretta per la presa in carico e la continuità assistenziale H (Ospedale) – T (Territorio). Determinazione 29 ottobre 2004.

- AIFA. Riclassificazione del regime di rimborsabilità – PHT. Determinazione 2 novembre 2010.

- Jommi C, Otto M, Armeni P, et al. OSFAR Report 34. Milan: Bocconi University; 2014.

- AIFA. Monitoraggio spesa farmaceutica. [ cited 2016 Mar 8]. Available from: http://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/sites/default/files/estratto_Monitoraggio_Spesa_Regionale_gen-nov_2015.pdf.

- APSS Provincia Autonoma di Trento. L’uso dei farmaci in Trentino. Rapporto. Trentino: APSS Provincia Autonoma di Trento; 2015.

- Garattini L, Van de Vooren K, Curto A. Will the reform of community pharmacies in Italy be of benefit to patients or the Italian National Health Service? Drugs Ther Perspect. 2012;28(11):23–26.