Over recent years, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has implemented or proposed several amendments to its methods and processes for the economic evaluation of health technologies within the National Health Service (NHS) [Citation1–Citation5]. These amendments have modified the ‘value’ that NICE assigns to health gains attributable to specific technologies when provided to patients with distinct characteristics. This raises fundamental equity issues that should be of concern to all NHS patients and other stakeholders.

1. Amendments to evaluation methods

Until 2009, common methods were used across all NICE appraisals of new health technologies [Citation6]. The cost-effectiveness of each technology was considered by comparing its incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) to a standard threshold of £20,000 to £30,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY).

NICE departed from this position with its ‘end-of-life’ guidance in 2009 [Citation1]. This amendment assigned ‘greater weight to QALYs achieved in the later stages of terminal diseases’ in specific cases where patients have a life expectancy of ‘less than 24 months’, the treatment extends life by ‘at least an additional 3 months,’ and the treatment is licensed for ‘small patient populations.’ NICE interpreted this amendment as permitting a higher threshold of £50,000 per QALY for ‘end-of-life’ technologies, increasing the likelihood of a positive recommendation [Citation3].

A subsequent amendment in 2011 took an alternative approach, assigning a lower discount rate to health gains for some technologies with treatment effects that are ‘substantial in restoring health and sustained over a very long period’ [Citation2]. This amendment increased the present value of the health gains associated with such technologies, lowering the ICER for each technology and increasing the likelihood of a positive recommendation.

In 2014, NICE proposed two new considerations that would justify a higher threshold: ‘burden of illness’ and ‘wider societal impact’ [Citation3,Citation7]. However, these proposals have not yet been implemented.

More recently, in April 2017, NICE adopted a higher threshold of between £100,000 and £300,000 per QALY when appraising treatments for ‘very rare diseases’ [Citation8]. The greater the QALY gain, the more ‘generous’ the threshold used when appraising such treatments. The maximum threshold of £300,000 per QALY is noted by NICE as being ‘ten times higher than the normal limit’.

NICE continues to use its ‘standard’ threshold of £20,000 to £30,000 per QALY when appraising technologies that do not meet any of the special criteria outlined in these recent amendments. The current Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme requires that this threshold not be changed until at least 2019 [Citation9].

2. Amendments to processes

Alongside amendments to its evaluation methods, several changes to NICE’s processes have been implemented that favor specific technologies or patients.

In 2011, the UK’s Department of Health implemented a ‘Cancer Drugs Fund’ (CDF) to pay for some cancer drugs that NICE had not recommended [Citation10]. Since 2016, NICE has been able to recommend that a cancer drug be funded through a reformed CDF as an alternative to a conventional ‘yes’ or ‘no’ recommendation [Citation4,Citation11]. Since NICE may continue to give a ‘yes’ recommendation if the ICER is sufficiently low, the CDF is effectively reserved for cancer drugs with high ICERs that would otherwise have received a ‘no’ recommendation.

In April 2017, NICE implemented several new processes, including ‘special arrangements’ to ‘manage the introduction’ of new technologies with a net budget impact in excess of £20m per year, and a ‘fast track’ appraisal process for ‘drugs costing up to £10,000 per QALY’ [Citation8].

3. Strengths and weaknesses of NICE’s amendments

A notable strength of NICE’s amended methods and processes is their relative transparency. NICE supports many of the principles of the ‘accountability for reasonableness’ framework, and each recent amendment has been subject to scrutiny through a public consultation process [Citation12–Citation15].

Yet there are also a number of weaknesses with these amendments. These include logical inconsistencies resulting from the use of arbitrary cutoffs and the conflation of QALY weights and threshold weights [Citation16]. By far the most egregious weakness is NICE’s apparent unwillingness to consider how its methods and processes impact the health of all NHS patients, rather than only those patients who stand to benefit from new technologies.

4. Opportunity cost and equity

NICE has been aware for some time that recommending new technologies has implications for other NHS patients. The 2004 edition of its ‘Guide to the methods of technology appraisal’ noted that ‘given the fixed budget of the NHS, the appropriate threshold is that of the opportunity cost of programmes displaced by new, more costly technologies’ [Citation17]. Similar language was included in the 2008 and 2013 editions [Citation6,Citation18].

Recent empirical research has estimated that a QALY is forgone by other NHS patients for approximately every £13,000 spent on new technologies [Citation19]. Although this research has been criticized, this is the best estimate currently available of the opportunity cost associated with NICE’s recommendations [Citation20,Citation21]. The researchers have also provided a tool which gives disaggregated estimates of QALY losses across different disease areas [Citation22].

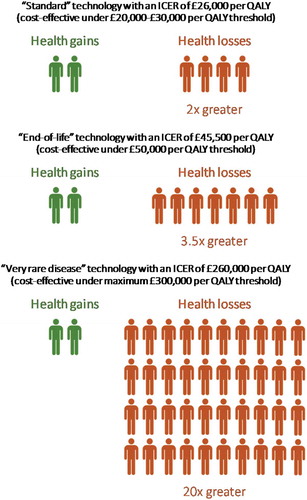

A technology with an ICER of £26,000 per QALY – within NICE’s ‘standard’ threshold range – would therefore be expected to displace two QALYs in other patients for every QALY gained by the beneficiaries (). Even technologies with ICERs below £20,000 per QALY, but above £13,000 per QALY, would be expected to diminish population health, since the health gains would be outweighed by the expected health losses.

Figure 1. Health gains and losses when NICE recommends a new health technology, assuming that a QALY is forgone by other NHS patients for every £13,000 spent on the technology.

For technologies with much higher ICERs, which NICE now recommends under its amended methods and processes, the magnitude of the expected health losses can be stark. An ‘end-of-life’ technology with an ICER of £45,500 per QALY (below the £50,000 per QALY ‘end-of-life’ threshold) would be expected to displace approximately 3.5 QALYs for every QALY gained, while a treatment for a ‘very rare disease’ with an ICER of £260,000 per QALY (below the maximum threshold for such technologies of £300,000 per QALY) would be expected to displace roughly 20 QALYs for every QALY gained ().

This has important equity implications. Equity can be considered in two dimensions: horizontal and vertical [Citation23,Citation24]. Horizontal equity requires that individuals with similar characteristics of ethical relevance be treated similarly. Vertical equity permits differential treatment of individuals with different characteristics. Critically, any given vertical equity position should be applied in a manner that respects horizontal equity; that is, even if individuals with different characteristics are treated differently, individuals should nevertheless be treated the same as others with similar characteristics [Citation25].

5. Violations of horizontal and vertical equity

If NICE were to adopt a vertical equity position under which equivalent health gains or losses for all individuals were given equal value, then satisfying horizontal equity would require that no technologies with an ICER above £13,000 per QALY be recommended, since the value of the expected health losses would exceed that of the health gains. Yet technologies with ICERs greater than £13,000 per QALY are routinely recommended by NICE. It follows that, if NICE were to adopt such a vertical equity position, then it would be implicitly violating the principle of horizontal equity every time it recommends a technology with an ICER greater than £13,000 per QALY.

Alternatively, NICE might adopt a vertical equity position in which equivalent health gains or losses are valued more for some individuals than for others. Indeed, this would appear to be NICE’s current position, since its recent amendments explicitly favor some patients at the ‘end of life,’ cancer patients, and patients with ‘very rare diseases.’ Under such a vertical equity position, NICE might consider that recommending a treatment for a ‘very rare disease’ that displaces 20 QALYs for every QALY gained is appropriate, since the QALYs are gained by patients for whom NICE assigns a greater value to health gains. Similarly, NICE might consider it appropriate to sacrifice multiple QALYs in ‘other’ patients for every QALY gained by patients with cancer, or those at the ‘end of life.’

The difficulty is that NICE does not know who these ‘other’ patients are that bear the opportunity cost of its recommendations. Since determinations regarding which health services to displace to fund NICE’s guidance are the responsibility of different decision-makers within the NHS, NICE cannot rule out the possibility that these patients also have cancer, are at the ‘end of life,’ or have a ‘very rare disease.’ By not giving these patients the same consideration as patients with similar characteristics who stand to benefit from new technologies, NICE is implicitly violating the principle of horizontal equity. NICE is also violating a key principle of procedural justice by not giving these patients the same ‘voice’ in its decision-making processes as that afforded to the identifiable beneficiaries of new technologies.

Furthermore, if some patients who bear the opportunity cost of new technologies are at the ‘end-of-life,’ then recommending a new technology with an ICER in excess of £13,000 per QALY might displace more health among ‘end-of-life’ patients than would be gained by similar patients. The same is true of patients with cancer or those with ‘very rare diseases.’ The higher the ICERs of new technologies, and the greater the proportion of such patients among those who bear the opportunity cost, the more likely that new technologies will diminish the health of the very same patient groups that NICE intends to prioritize [Citation16]. This represents an inconsistent application of NICE’s preferred vertical equity position.

6. Future steps

It is clear that NICE’s current methods and processes are problematic. The routine use of thresholds in excess of £13,000 per QALY means that many of NICE’s recommendations may be detrimental to population health, since the expected health losses exceed any resulting health gains.

The option for NICE to recommend that some cancer treatments which are not cost-effective be funded through the CDF not only constitutes a misuse of limited health care resources, but also creates perverse incentives for industry to misdirect research and development resources toward treatments for which the opportunity cost far exceeds any benefits to patients [Citation11].

NICE’s current methods and processes are implicitly inequitable. They fail to consider the impact of NICE’s recommendations upon all NHS patients, and they prioritize the health of the identifiable beneficiaries of new technologies at the expense of other patients, including those with similar characteristics.

It should be emphasized that a key strength of NICE, as noted earlier, is its relative transparency. It is because of this transparency that academics can critique NICE’s methods and processes and propose alternative approaches. Since NICE is an international leader in health technology assessment, any lessons learned from these attempts to modify its methods and processes are also of interest to policy-makers and academics in other jurisdictions who face similar challenges.

In order to make more equitable recommendations in future – and adhere to the principles of procedural justice – NICE should undertake further research to understand the characteristics of all patients affected by its recommendations. NICE should then modify its methods and processes so that it no longer recommends new technologies unless the value of the expected health gains exceeds the value of the expected health losses, where the latter is informed by empirical research into the magnitude of the expected health losses and the characteristics of those patients affected [Citation26].

In the meantime, NICE’s continued use of inappropriately high thresholds, and its failure to consider the characteristics of all NHS patients affected by its recommendations, is detrimental to population health and violates the principles of horizontal and vertical equity.

Declaration of interest

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Appraising life-extending, end of life treatments [Internet]. NICE. 2009 Jul. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-tag387/resources/appraising-life-extending-end-of-life-treatments-paper2

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Discounting of health benefits in special circumstances [Internet]. NICE. 2011 Jul. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta235/resources/osteosarcoma-mifamurtide-discounting-of-health-benefits-in-special-circumstances2

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Consultation paper - value based assessment of health technologies [Internet]. NICE. 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-guidance/NICE-technology-appraisals/VBA-TA-Methods-Guide-for-Consultation.pdf

- NHS England Cancer Drugs Fund Team. Appraisal and funding of cancer drugs from July 2016 (including the new Cancer Drugs Fund) - a new deal for patients, taxpayers and industry. NHS England [Internet]. 2016 Jul. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/cdf-sop.pdf

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and NHS England. Proposals for changes to the arrangements for evaluating and funding drugs and other health technologies appraised through NICE’s technology appraisal and highly specialised technologies programmes [Internet]. NICE and NHS England. 2016 Oct. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/our-programmes/technology-appraisals/NICE_NHSE_TA_and_HST_consultation_document.pdf

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2008. London: NICE; 2008.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods of technology appraisal consultation [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 May 2]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-technology-appraisal-guidance/methods-of-technology-appraisal-consultation

- NICE. Changes to NICE drug appraisals: what you need to know. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. 2017 Apr 4 [cited 2017 May 2]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/news/feature/changes-to-nice-drug-appraisals-what-you-need-to-know

- Department of Health and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. The pharmaceutical price regulation scheme 2014 [Internet]. Department of Health and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry; 2013 Dec. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/282523/Pharmaceutical_Price_Regulation.pdf

- Department of Health. Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS [Internet]. Department of Health. 2010 Jul. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213823/dh_117794.pdf

- McCabe C, Paul A, Fell G, et al. Cancer drugs fund 2.0: a missed opportunity? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:629–633. DOI:10.1007/s40273-016-0403-2

- Daniels N, Sabin J. The ethics of accountability in managed care reform. Health Aff. 1998;17:50–64. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9769571

- Schlander M. NICE accountability for reasonableness: a qualitative study of its appraisal of treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:207–222. DOI:10.1185/030079906X159461

- Daniels N. Accountability for reasonableness. BMJ. 2000;321:1300–1301. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11090498

- Daniels N, Sabin JE. Accountability for reasonableness: an update. BMJ. 2008;337:a1850. DOI:10.1136/bmj.a1850

- Paulden M, O’Mahony JF, Culyer AJ, et al. Some inconsistencies in NICE’s consideration of social values. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:1043–1053. DOI:10.1007/s40273-014-0204-4

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2004. London: NICE; 2004.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013 [Internet]. London: NICE; 2013 Apr. Available: http://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9

- Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Methods for the estimation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cost-effectiveness threshold. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19:1–503,v–vi. DOI:10.3310/hta19140

- Barnsley P, Towse A, Karlsberg Schaffer S, et al. Critique of CHE research paper 81: methods for the estimation of the NICE cost-effectiveness threshold [Internet]. Office of Health Economics. 2013. Available from: https://www.ohe.org/publications/critique-che-research-paper-81-methods-estimation-nice-cost-effectiveness-threshold

- Claxton K, Sculpher M. Response to the OHE critique of CHE Research paper 81 [Internet]. University of York. 2013. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/che/documents/Response%20to%20the%20OHE%20critique%20of%20CHE%20Research%20paper%2081.pdf

- Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Opportunity Cost Calculator [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 May 02]. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/che/research/teehta/thresholds/

- Culyer AJ. Equity - some theory and its policy implications. J Med Ethics. 2001;27:275–283. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11479360

- Culyer AJ. Need: the idea won’t do—but we still need it. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:727–730. DOI:10.1016/0277-9536(94)00307-F

- Paulden M. Opportunity cost and social values in health care resource allocation [Internet] [PhD]. McCabe C, editor. University of Alberta; 2016. DOI:10.7939/R3M902D4P

- Sendi P, Gafni A, Birch S. Opportunity costs and uncertainty in the economic evaluation of health care interventions. Health Econ. 2002;11:23–31. DOI:10.1002/hec.641