ABSTRACT

Objective: Endometriosis impacts health-related quality of life. The objective was to assess the validity and responsiveness of the Health-Related Productivity Questionnaire, version 2 (HRPQ).

Methods: Outcome measures (Endometriosis Health Profile-30; pain scales; and global assessment) from Elaris Endometriosis I and II clinical trials (EM-I, EM-II) were used. Validity testing using Cohen’s conventions was assessed. Known-groups validity was evaluated using generalized linear models comparing clinical responders, assessment of change, and the endometriosis impact. The effect size (ES) and standard error of means were calculated to evaluate responsiveness.

Results: 871 and 815 women participated in the EM-I and EM-II trials. The total hours of lost work among employed women were 16.5 (±11.4) hours per week for EM-I and 15.2 (±11.3) for EM-II. The total hours of lost work among the household group were 8.3 (±8.7) hours for EM-I and 8.4 (±9.0) hours for EM-II. HRPQ discriminated between all known group assessments tested. Correlations for the HRPQ compared to other measures were small to moderate. Moderate to large ES was observed and the ability of the HRPQ to detect change was strong using patient-reported impressions.

Conclusion: The HRPQ is a valid and responsive tool for evaluating patient-reported productivity at work and at home among women with endometriosis.

1. Background

Endometriosis is a condition characterized by symptoms that can have severe impacts on health-related quality of life (HRQL) and disrupt daily activities, such as household cooking, shopping, cleaning and childcare, and paid employment [Citation1–4]. Dysmenorrhea (pain during menstruation), dyspareunia (painful intercourse), and chronic non-menstrual pelvic pain [Citation5] are the primary symptoms of endometriosis which affects about 176 million women worldwide in the prime employable years between 15 and 49 years old [Citation6].

The physical demands of household chores and type of employment can be severely impacted due to symptoms of endometriosis, but career growth within a workplace may also be disrupted by the increase in medical appointments and physical strain related to endometriosis [Citation2]. These factors can increase the risk for greater absenteeism (missed work) and presenteeism (reduced performance at work). The Global Study of Women’s Health, for example, documented the lost productivity due to endometriosis and effect on HRQL. As the disease severity increased among women with endometriosis, absenteeism, presenteeism, and work productivity loss increased as well [Citation7]. Furthermore, as the number of symptoms women experience increases, their HRQL declines and the negative impact on employment and household chores rises [Citation8].

Due to the potential impact on an individual’s HRQL, measuring absenteeism and presenteeism for both paid employment and household chores simultaneously is imperative and should be included as an evaluation endpoint during clinical product development. Many generic productivity patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires have been developed and used for similar purposes; the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) [Citation9,Citation10], Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) [Citation11–14], Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) [Citation15], Health and Work Questionnaire (HWQ) [Citation16], Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS) [Citation17], Health and Labor Questionnaire (HLQ) [Citation18]. However, none of the above measures capture absenteeism and presenteeism for both paid work and household chores with respect to percent of time and hours lost.

One measure, the Health-Related Productivity Questionnaire, version 2 (HRPQ), evaluates the impact of disease on absenteeism and presenteeism for employment and household chores, which is a key advantage of this questionnaire over other productivity measures. The content of the HRPQ was initially developed among patients with Parkinson’s disease through focus group discussions and later adapted for use in a Phase 1 multicenter clinical trial among patients with infectious mononucleosis [Citation19]. The HRPQ was further validated in a general population and used to assess lost productivity among women with self-report endometriosis [Citation20]. The purpose of this post hoc analysis was to assess the validity and responsiveness of the HRPQ among women with endometriosis when measuring the impact of disease on absenteeism and presenteeism for both paid employment and household chores.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source and sample

The source data for this evaluation were the Elaris Endometriosis I and II clinical trials (EM-I and EM-II; NCT01620528 and NCT01931670) [Citation21]. The trial program included two Phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials among women with moderate to severe endometriosis-associated pain. The primary endpoint was evaluated after 3 months of treatment, but treatment continued for 6 months total; the trial included a post-treatment follow-up period for 12 months. Information on individual trial results have been published elsewhere [Citation21].

The EM-I trial recruited 875 women who were randomized to one of the three parallel dose groups in a 3:2:2 ratio to receive daily doses of either placebo (n = 375), elagolix 150 mg once daily (n = 250) or elagolix 200 mg twice a day (n = 250) for 6 months. The EM-II trial recruited 788 women who were randomized to one of the three parallel dose groups in a 3:2:2 ratio to receive daily doses of either placebo (n = 338), elagolix 150 mg once daily (n = 225) or elagolix 200 mg twice a day (n = 225) for 6 months.

2.2. Compliance with ethical standards consent to participate

The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, local independent ethics committee/institutional review board requirements, and good clinical practice guidelines. Shulman Associates IRB conducted the majority of the IRB approvals (M12-665 IRB approval number 201202559 approval date 11 April 2012; M12-671 IRB approval number 201208471, approval date on 16 November 2012). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g. protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

2.3. Patient-reported outcome measures

2.3.1. Health-related productivity questionnaire (HRPQ)

The content of the HRPQ was initially developed among patients with Parkinson’s disease and later adapted for use in a Phase I clinical trial for infectious mononucleosis and was designed as a daily diary to document absenteeism and presenteeism [Citation19]. A one-week recall version of the HRPQ was validated in the general population and exploration into lost productivity due to endometriosis among women was also assessed [Citation20]. The HRPQ can be adapted to be disease-specific but the psychometric properties of the instrument should be evaluated for each population being assessed.

The self-reported, 9-item, 1-week recall HRPQ (version 2) was utilized in the EM-I and EM-II trials. The HRPQ follows skip patterns so that the items are applicable to those who are employed outside the home (e.g. full- or part-time employment) and those who work inside the home. The HRPQ asks about the number of hours the subject was scheduled to work/planned to do household chores then asks the number of hours missed due to their condition so that absenteeism can be calculated. The subject is also asked about the percent impact on their work to calculate presenteeism. For these analyses, the responses to the first HRPQ question determined the participant’s working status; responses to currently employed full time or part time were included as ‘employed’ and not currently employed were included as ‘non-employed’. The number of hours lost, percent of the patient’s scheduled work that is lost due to absenteeism and lost due to presenteeism, and overall percent of work lost can be calculated specifically to workplace and to household.

2.3.2. Endometriosis health profile-30 (EHP-30)

EHP-30 is a disease-specific health-related quality of life instrument with six supplementary modules. The EHP-30 core items are made up of the following domains: pain; control and powerlessness; emotional well-being; social support; self-image. The EHP-30 has been developed using patient interviews and has undergone evaluations of reliability, validity, and responsiveness [Citation22]. The EM-I and EM-II trials included the EHP-30 core items and the EHP-30 sexual relationship module, which included five items. The measure was scored according to the developer’s manual [Citation22]. The EHP-30 Pain Domain was utilized for the concurrent validity analyses of the HRPQ because pain impact is the most likely proximal concept for employment and household impacts.

2.3.3. Endometriosis pain numeric rating scale (pain NRS)

The Pain NRS was used to characterize endometriosis pain as an average pain score over the number of days when the subject reported NRS during the 35 calendar days immediately prior to and including the study visit date. The patient was asked about their worst endometriosis pain over the last 24 h.

2.3.4. Dysmenorrhea (DYS) and non-menstrual pelvic pain (NMPP)

The daily assessment of DYS and NMPP was measured by the Endometriosis Daily Pain Impact Items to assess dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain using a daily electronic diary [Citation23]. For DYS, responders were to ‘choose the item that best describes your pain during the last 24 hours when you had your period,’ and for NMPP ‘choose the item that best describes your pain during the last 24 hours without your period.’ Pain responses of ‘None’ (no discomfort), ‘Mild’ (Discomfort, but I was easily able to do the things I usually do), ‘Moderate’ (I had some difficulty doing the things I usually do), and ‘Severe’ (I had a great difficulty doing the things I usually do) were assigned a score of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. At baseline, scoring was averaged over the 35 calendar days immediately prior to and including the first study drug dose date.

Pain related to DYS and NMPP was assigned based upon the patient’s response to the question: ‘Did you have your period in the last 24 hours?’ If the patient’s response was yes, the pain was attributed to DYS; if the patient’s response was no, then the pain was attributed to NMPP. The monthly average pain scores for DYS and NMPP were averaged separately over the number of days when the patient-reported DYS or NMPP-related pain within each respective time window [Citation21].

2.3.5. Patient global assessment of change (PGIC)

The PGIC item in the study was, ‘Since I started taking the study medication, my endometriosis relatedpain has: very much improved (1), much improved (2), minimally improved (3), no change (4), minimally worse (5), much worse (6), very much worse (7).’ [Citation24]

2.4. Analytic approach

Trials EM-I and EM-II were analyzed separately. All analyses used the intent-to-treat (ITT), observed cases (OC) sample for all time points analyzed. No values for missing evaluations, questionnaires, or PRO data were imputed. Patients without an evaluation on a scheduled assessment were excluded from the OC analyses for that evaluation. All analyses were run in SAS™ version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, USA) and a p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Two patient groups, employed (full-time or part-time paid employment) and household (employed and not employed), were defined for this study.

2.4.1. Descriptive

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, range, frequencies for categorical data) were calculated for the sample, sociodemographic characteristics, clinical and gynecologic characteristics, and patient-reported outcome data at Baseline (Day 1) for each trial and by employment status. Comparisons were made using t-tests for continuous data and chi-square tests for categorical data.

To assess item performance and HRPQ structure, HRPQ scores (hours of lost work due to absenteeism, hours of lost work due to presenteeism, total hours of lost work, percent of scheduled work lost due to absenteeism, percent of scheduled work lost due to presenteeism, and percent of scheduled work lost in total) were calculated according to the developer’s manual at Baseline (Day 1) for paid employment and household (employed and non-employed), and by trial.

2.4.2. Construct validity

Validity assesses whether or not the instrument measures the concept(s) it purports to measure. Convergent validity involves demonstrating that different measures of the same concept substantially correlate. The HRPQ was the only measure of productivity used in EM-I and EM-II therefore, low correlation with other measures were expected during the convergent validity testing. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients at Day 1, Month 3, and Month 6 were assessed using Cohen’s interpretation of correlation coefficients (0.10 -small; 0.30 – medium; and 0.50 – large) [Citation25]. Convergent validity was evaluated by the magnitude and relationship between HRPQ absenteeism and HRPQ presenteeism for hours lost and percent lost and the EHP-30 Pain Domain, monthly average of the Pain NRS, and monthly average for DYS and NMPP.

Known-groups validity testing was evaluated using the PGIC dichotomous scale (improvement versus no change or worsening) at Month 3. Additional generalized linear model (GLM) was assessed for paid employment and household absenteeism and presenteeism and Scheffe’s post hoc pairwise comparisons were used to test for differences between the specific levels of each grouping by Worst Pain NRS at Day 1 (<4 mild; 4–8 moderate; >8 severe). By using Scheffe’s method, adjustments for multiple comparisons have been made; this is consistent with published recommendations [Citation26].

Responsiveness, or sensitivity to change, refers to the extent to which the instrument can detect true change in patients known to have changed in clinical status [Citation27]. The change (Month 3 – Baseline) in HRPQ was compared across meaningful levels of change based on several assessments. The assessments are similar to those of the known group analyses, however responsiveness focuses on the change in score. To investigate the HRPQ ability to detect change among groups we know to have changed, clinical responders (responders or non-responders for dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain based on the trial endpoints) and endometriosis impact (using the EHP-30 domains) were used as the identifier.

Effect size (ES), standard error of means (SEM), Day 1 half standard deviation, and Cohen’s d were also calculated for the HRPQ. ES is a quantitative measure of change that provides a means of standardizing the quantification for comparison between groups [Citation28]. The ES assessment evaluates the HRPQ responsiveness over time and was calculated by subtracting Day 1 scores from Month 3 scores and dividing by the Month 3 standard deviation for absenteeism and presenteeism (i.e. end-start/end). This approach follows standard practice for outcomes research [Citation29,Citation30]. ES was interpreted as small (0.20), moderate (0.50), or large (0.80), following the guidelines proposed by Cohen [Citation25]. SEM estimates for the HRPQ was calculated based on Month 3 data with the value of 1 SEM being considered a meaningful change [Citation29,Citation30].

3. Results

A total of 871 women participated in the EM-I trial and 815 in the EM-II trial. The mean age of the women in the EM-I and EM-II trials was 31.5 (SD 6.2) and 33.2 (SD 6.7), respectively. Significant group differences by employed and not employed were seen for age in the EM-II trial (p = 0.0174). The majority were White (87.1% EM-I and 89.2% EM-II) and not-Hispanic or Latino (84.0% EM-I and 86.6% EM-II) (). For the monthly assessment of pain, there were significant differences between employed and not employed for pain NRS (EM-I p = 0.0035; EM-II p = 0.0003), dysmenorrhea (EM-I p = 0.0161; EM-II p = 0.0021), and dyspareunia (only EM-I significant p = 0.0063; EM-II p = 0.1979), with the not-employed group reporting greater pain. EHP-30 domain scores are presented to characterize the sample and significant differences between employed and not employed persisted for all domains except sexual relationship in the EM-II trial with greater impact seen among the women not employed (EM-II: pain p = 0.0202; control and powerlessness p = 0.0031; emotional well-being p = 0.0006; social support p = 0.0009; self-image p = 0.0155). Only control and powerlessness (p = 0.0257), self-image (p = 0.0057), and sexual relationship (p = 0.0161) were significant for the EM-I trial. The sample’s clinical characteristics and outcomes are detailed elsewhere [Citation21].

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics on day 1

The Day 1 calculated HRPQ scores represent the baseline impact of endometriosis on employed women and impact on the household (both employed and non-employed women) for both EM-I and EM-II trials (). Among the women working full or part-time, the women reported being absent from work 3.2 (±5.3) hours per week for EMI-I and 2.9 (± 5.6) hours for EM-II due to endometriosis at Day 1. Among employed women, presenteeism at baseline was reported to be 13.4 (±9.9) lost hours while at work for EM-I and 12.5 (± 10.1) hours for EM-II. The total hours of lost work among employed women were 16.5 (±11.4) hours per week for EM-I and 15.2 (± 11.3) hours for EM-II. Among employed women, the percent of scheduled work lost in total was 45.3% (±27.2%) for EM-I and 43.7% (± 27.7%) for EM-II.

Table 2. HRPQ calculated scores for paid employment and household chores (Employed and not-employed) for EM-I and EM-II on day 1

When examining the household impact, the hours of lost time (absenteeism) at Day 1 were 4.7 (±5.5) for EM-I and (4.8 ± 6.0) for EM-II. The household group reported 3.6 (±4.9) hours of presenteeism for EM-I and 3.7 (± 4.7) hours for EM-II. The total hours of lost work among the household group were 8.3 (± 8.7) hours for EM-I and 8.4 (± 9.0) hours for EM-II. The percent of work lost in total was 66.4% (±30.4%) for the EM-I Household group and 62.8% (±29.2%) for EM-II ().

The correlations for the HRPQ and the EHP-30 Pain Domain, monthly average of the Pain NRS, and monthly average for DYS and NMPP at Day 1 with absenteeism and presenteeism for both trials were in the small to moderate range (up to 0.35). With only a few exceptions, the correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.05) at all timepoints; all measures; and both trials. The exceptions were NMPP correlation with hours lost due to presenteeism among the household group (EM-I), DYS and NMPP correlation with hours lost due to presenteeism for paid employment (EM-II), and NMPP correlations with hours and percent lost due to presenteeism in the household group (). Correlations between the HRPQ and the PRO measures were evaluated at Month 3 and Month 6 and increased over time and by Month 6, correlations between absenteeism and presenteeism and PRO measures were moderate to strong (up to 0.68; data not shown).

Table 3. Convergent validity HRQP with other PRO measures for paid employment and household chores at day 1, EM-I and EM-II

The patient’s Worst Pain NRS data were grouped at Day 1 to assess the known-groups validity for HRPQ responses (). Presented in , as Worst Pain moves from Mild to Severe across the groups, the HRQP values of lost productivity increase, for the most part. For example, among employed women, absenteeism for those reporting mild worst pain had 2.0 (±3.4) lost hours, 3.4 (±5.6) lost hours for the moderate group, and 4.7 (±5.9) for the severe group (EM-I). Among the employed women, presenteeism among the mild worst pain group was 11.9 (±9.6), 13.5 (±9.7) lost hours for the moderate group, and 16.4 (±11.5) lost hours for the severe group (EM-I). Statistically significant differences were identified across Worst Pain NRS groups when comparing mild and severe Worst Pain NRS values for employed and household and for absenteeism and presenteeism (EM-I); group differences were not always statistically different in the EM-II trial ().

Table 4. Known-groups validity HRPQ by worst pain NRS on day 1, EM-I and EM-II

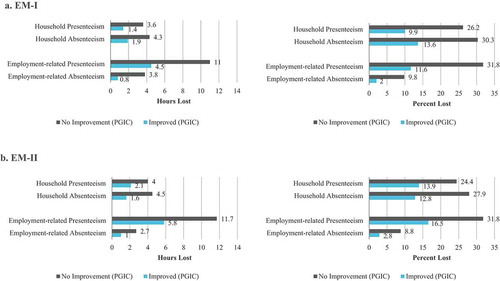

When examining the PGIC at Month 3, comparing women who reported at least a minimal improvement versus those who reported no change or worsening, every HRPQ assessment for both the paid employment group and the household group showed statistically significant (p < 0.001) discrimination in both trials ().

Figure 1. Known-groups validity: HRPQ by PGIC at month 3 for household chores and paid employment, hours and percent lost, EM-I and EM-II. (a). EM-I. (b). EM-II

Moderate to large effect sizes were observed for absenteeism and presenteeism in both trials ( reports EM-I only; EM-II data were similar). Ranges presented here are inclusive of both the EM-I and EM-II trials. Generally, among the paid employment group the absenteeism (hours and percent) effect sizes were moderate (−0.25 to −0.34) and −0.53 to −0.87 for presenteeism. The household group had moderate to large effect sizes (−0.44 to −0.80 range for absenteeism and −0.26 to −0.67 for presenteeism). All assessments of HRPQ SEM estimates were greater than 1 in both trials indicating meaningful changes across paid employment/household absenteeism and presenteeism.

Table 5. Responsiveness: effect size and SEM of the HRPQ, EM-I

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the psychometric properties of the HRPQ instrument among women with moderate to severe endometriosis, concluding that the HRPQ is a valid, responsive, and a discriminate measure of productivity among women with endometriosis. When demonstrating the value of a new product, the direct impact of a health condition is valuable in economic modeling of productivity. As such, lost productivity can be included in the value propositioning of new products. Thus, having valid and responsive measures to evaluate self-reported productivity are essential to demonstrating a value proposition. The HRPQ provides support for such assessments and modeling efforts. As found in this study, the high burden that endometriosis poses on women who are of prime working-age, and often have high domestic and household responsibilities, should be represented when studying interventions.

Endometriosis has an impact on aspects of HRQL such as daily activities, sexual relationships, social activities, employment, and physical and psychological aspects of daily living [Citation1–Citation4,Citation8]. Soliman and colleagues (2017) conducted a very large web-based survey among women age 18–49 in the US to evaluate the effect of endometriosis symptoms on productivity, the prevalence of endometriosis, and other characteristics about the women. The prevalence screener had 59,411 women respond, 9.9% (n = 5,879) eligible to complete the survey, and 2.2% (n = 1,318) reported having endometriosis and at least 1 h of scheduled household chores in the past 7 days. The results show that as symptom severity and the number of symptoms increase so do the negative impacts on HRQL [Citation8]. Because endometriosis is a pervasive condition that reflects a range of symptom experiences such as chronic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, menstrual irregularities, and infertility and there are higher rates of mental health comorbidities (e.g. anxiety and depression) it is difficult to pinpoint etiology. The symptom and impacts are complex and intertwined [Citation31–33]. A multidisciplinary care approach may improve the varied impacts endometriosis has in women’s lives and begin to recede the burden on HRQL and productivity.

One limitation of this study was that this was a post hoc analysis using data from the EM-I and EM-II trials; psychometric analyses to assess the reliability of the HRPQ such as reproducibility were not performed as the trial design was not optimal for assessing reproducibility. Further, given that the HRPQ is not a scaled instrument, internal consistency reliability was not assessed. All data were based on self-report, increasing bias and limiting the potential accuracy of responses. Interpretation of this study for other therapeutic areas should be used with caution as these findings about the HRPQ’s performance are specific to the context of use, the moderate to severe endometriosis population. The HRPQ may perform differently in other illnesses or treatments and should be tested accordingly. Finally, data were not imputed in this assessment of the instrument’s performance. The HRPQ scoring instructions permit missing data to be filled with zero and state that the hours of missed time cannot be more than the hours of scheduled time. Missing, or illogical data, cannot be imputed for the unique items of the HRPQ so if the target population is at risk of high volume of missing data caution should be used.

The HRPQ fills a gap in the current patient-reported landscape for work productivity instruments. The HRPQ can gather self-reported information about not only employment productivity impacts but also household productivity impacts. This is novel and critical, particularly among women of prime childrearing age. Often, productivity measurement is limited to employment and does not represent important domestic responsibilities. In the trial sample, the mean age was early thirties (31.5 for EM-I and 33.2 for EM-II) so the sample aligns with a demographic of women with tremendous responsibilities. Having a valid instrument to reflect health impacts on those responsibilities is essential. Just over 20% of the women in the trial have not paid employment (22.2% in EM-I; 23.2% in EM-II). Omitting the household responsibilities and impacts on productivity would not represent the full burden of endometriosis on women. Although monetary value cannot be placed on household impacts, as there is no salary, the data should be represented. Treatment evaluations should reflect endpoints that represent how patients feel, function, and survive; even if the function is not work-related. The HRPQ is a valid and responsive measure for documenting employment-related and household productivity impacts.

5. Conclusion

This post hoc analysis study demonstrated the validity and responsiveness of a tool that can be used to document absenteeism and presenteeism, both at work and at home among women with endometriosis.

The HRPQ can be used in interventional studies to document the productivity impacts endometriosis has on women. Understating the direct cost of endometriosis needs to be coupled with the indirect cost of endometriosis and HRQL impacts to provide a more complete societal burden of illness. Interventions that are successful in mitigating the burden experienced by women have the potential to improve HRQL and well as productivity among women with endometriosis.

Article Highlights

The Health-Related Productivity Questionnaire, version 2 (HRPQ) is a patient-reported measure of productivity that was assessed for validity and responsiveness in this study.

This was a post hoc analysis using data from the Elaris Endometriosis I and II clinical trials (EM-I n=871; EM-II n=815).

The total hours of lost work among employed women were 16.5 (±11.4) hours per week for EM-I and 15.2 (±11.3) for EM-II; the total hours of lost work among the household group was 8.3 (±8.7) hours for EM-I and 8.4 (±9.0) hours for EM-II.

HRPQ discriminated between all known group assessments tested.

Correlations for the HRPQ compared to other measures were small to moderate and stronger over time. Moderate to large ES was observed and the ability of the HRPQ to detect change was strong using patient-reported impressions of change.

The HRPQ is a valid and responsive tool for evaluating patient-reported productivity at work and at home among women with endometriosis.

Declaration of interest

A Soliman and M Snabes are employees of and own stock/stock options in AbbVie. R Pokrzywinski, K Coyne, and J Chen are employees of Evidera, who were paid consultants to AbbVie in connection with this study. S Agarwal is Director of Fertility Services in the University of California (UC) San Diego Department of Reproductive Medicine, Director of the UC San Diego Center for Endometriosis Research and Treatment and has served in a consulting role on research to AbbVie. C Coddington is a professor in the division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota and has served in a consulting role on research to AbbVie.

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author Contributions

RP, AMS, JC, KSC contributed to the analytic approach, interpretation, and reporting of the research. JC also served as the statistical programmer. MS, SKA, CC provided ongoing clinical and scientific feedback about the methods and findings of the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinicaltrials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualifiedresearchers.html.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing services were provided by Danielle Rodriguez, PhD, MPH.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, et al. The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a critical narrative review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013 Nov-Dec;19(6):625–639.

- Fourquet J, Gao X, Zavala D, et al. Patients’ report on how endometriosis affects health, work, and daily life. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(7):2424–2428.

- Moradi M, Parker M, Sneddon A, et al. Impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2014 Oct;4(14):123.

- Nnoaham K, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366–373.e8.

- Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, et al. Endometriosis and infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010 Aug;27(8):441–447.

- Adamson GD, Kennedy S, Hummelshoj L. Creating solutions in endometriosis: global collaboration through the World Endometriosis Research Foundation. London, England: SAGE Publications Sage UK; 2010.

- Nnoaham K, Sivananthan S, Hummelshoj L, et al., editors. Global study of women’s health: a multi-centre study of the global impact of endometriosis. 26th Annual Meeting of European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology; 2010 June 27–30;Rome, Italy.

- Soliman AM, Coyne KS, Gries KS, et al. The effect of endometriosis symptoms on absenteeism and presenteeism in the workplace and at home. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(7):745–754.

- Chirban JT, Jacobs RJ, Warren J. et al. The 36-item short form health survey (SF-36) and work productivity and the impairment (WPAI) questionnaire in panic disorder. Dis Manage Health Outcomes. 1997;1(3):154–164.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993 Nov;4(5):353–365.

- Davies GM, Santanello N, Gerth W, et al. Validation of a migraine work and productivity loss questionnaire for use in migraine studies. Cephalalgia. 1999 Jun;19(5):497–502.

- Lerner D, Amick BC 3rd, Rogers WH, et al. The work limitations questionnaire. Med Care. 2001 Jan;39(1):72–85.

- Lerner DJ, Amick BC 3rd, Malspeis S, et al. A national survey of health-related work limitations among employed persons in the United States. Disabil Rehabil. 2000 Mar 20;22(5):225–232.

- Lerner DJ, Amick BC 3rd, Malspeis S, et al. The migraine work and productivity loss questionnaire: concepts and design. Qual Life Res. 1999 Dec;8(8):699–710.

- Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, et al. The world health organization health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ). J Occup Environ Med. 2003 Feb;45(2):156–174.

- Halpern MT, Shikiar R, Rentz AM, et al. Impact of smoking status on workplace absenteeism and productivity. Tob Control. 2001;10(3):233–238.

- Endicott J, Nee J. Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS): a new measure to assess treatment effects. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):13–16.

- van Roijen L, Essink-Bot ML, Koopmanschap MA, et al. Labor and health status in economic evaluation of health care. The health and labor questionnaire. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1996 Summer;12(3):405–415.

- Kumar RN, Hass SL, Li JZ, et al. Validation of the Health-Related Productivity Questionnaire Diary (HRPQ-D) on a sample of patients with infectious mononucleosis: results from a phase 1 multicenter clinical trial. J Occup Environ Med. 2003 Aug;45(8):899–907.

- Tundia N, Hass S, Fuldeore M, et al. Validation and us Population norms of health-related productivity questionnaire. Value Health. 2015;3(18):A24.

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6;377(1):28–40.

- Jones G, Kennedy S, Barnard A, et al. Development of an endometriosis quality-of-life instrument: The endometriosis health profile-30. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Aug;98(2):258–264.

- Wyrwich KW, O’Brien CF, Soliman AM, et al. Development and validation of the endometriosis daily pain impact diary items to assess dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pelvic pain. Reprod Sci. 2018 Nov;25(11):1567–1576.

- Hurst H, Bolton J. Assessing the clinical significance of change scores recorded on subjective outcome measures. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004 Jan;27(1):26–35.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc,; 1988.

- Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014 Sep;34(5):502–508.

- Hays RD, Revicki D. Reliability and validity (including responsiveness). In: Fayers P, Hays RD, editors. Assessing quality of life in clinical trials: methods and practice. Assessing quality of life in clinical trials. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 25–39.

- Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989 Mar;27(3 Suppl):S178–89.

- Wyrwich KW, Nienaber NA, Tierney WM, et al. Linking clinical relevance and statistical significance in evaluating intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. Med Care. 1999a May;37(5):469–478.

- Wyrwich KW, Tierney WM, Wolinsky FD. Further evidence supporting an SEM-based criterion for identifying meaningful intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999b Sep;52(9):861–873.

- Vitale SG, La Rosa VL, Vitagliano A. et al. Sexual function and quality of life in patients affected by deep infiltrating endometriosis: current evidence and future perspectives. J Endometriosis Pelvic Pain Disord. 2017;9(4):270–274.

- Vitale SG, La Rosa VL, Rapisarda AMC, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and psychological well-being. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017 12.;38(4):317–319.

- Lagana AS, La Rosa VL, Rapisarda AMC, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: impact and management challenges. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:323–330.