ABSTRACT

Introduction

The statistical quality of many trial-based economic evaluations is poor. When conducting trial-based economic evaluations, researchers often turn to national pharmacoeconomic guidelines for guidance. Therefore, this study reviewed which recommendations are currently given by national pharmacoeconomic guidelines on the statistical analysis of trial-based economic evaluations.

Areas covered

40 national pharmacoeconomic guidelines were identified. Data were extracted on the guidelines’ recommendations on how to deal with baseline imbalances, skewed costs, correlated costs and effects, clustering of data, longitudinal data, and missing data in trial-based economic evaluations. Four guidelines (10%) were found to include recommendations on how to deal with baseline imbalances, five (13%) on how to deal with skewed costs, and seven (18%) on how to deal with missing data. Recommendations were very general in nature and recommendations on dealing with correlated costs and effects, clustering of data, and longitudinal data were lacking.

Expert opinion

Current national pharmacoeconomic guidelines provide little to no guidance on how to deal with the statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations. Since the use of suboptimal statistical methods may lead to biased results, and, therefore, possibly to a waste of scarce resources, national agencies are advised to include more statistical guidance in their pharmacoeconomic guidelines.

1. Introduction

As resources are scarce, decision-makers need to decide which health-care interventions to reimburse with the available resources while at the same time maximizing health benefits [Citation1]. Economic evaluations seek to inform decision-makers by assessing whether the additional health effects of an intervention justify its additional costs as compared to an alternative intervention [Citation1]. Many grant organizations demand that economic evaluations are conducted alongside clinical trials and the results of such so-called trial-based economic evaluations are increasingly being used to inform health-care decision-making [Citation2–Citation4]. In various countries, cost-effectiveness is even established as a formal decision criterion for the pricing and/or reimbursement of pharmaceuticals and other health-care technologies [Citation5–Citation9].

As a consequence, national agencies, such as the English National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Dutch Health Care Institute, developed guidelines containing principles and recommendations for the design, execution, and reporting of economic evaluations [Citation5–Citation8]. When conducting trial-based economic evaluations, researchers frequently turn to such pharmacoeconomic guidelines for guidance. Also, in an increasing number of countries, researchers and health technology manufacturers are obliged to follow pharmacoeconomic guidelines when preparing an economic evaluation as part of the application process for reimbursement of a new drug and/or health-care technology [Citation5–Citation8]. Research suggests that the introduction of national pharmacoeconomic guidelines has led to an improved reporting quality of trial-based economic evaluations in some areas (e.g. obstetrics) [Citation10–Citation13], whereas this effect was not observed in others (e.g. gynecology) [Citation11,Citation14,Citation15].

Despite the existence of many national pharmacoeconomic guidelines, the statistical quality of trial-based economic evaluations is typically poor [Citation11,Citation16–Citation19]. Baseline imbalances, the skewed nature of cost data, the correlation between costs and effects, the clustering of data, and the longitudinal nature of cost and/or data are often unaccounted for in trial-based economic evaluations [Citation11,Citation16–Citation19]. On top of that, missing data are frequently handled using ‘naïve’ imputation methods, such as mean imputation and last observation carried forward [Citation11,Citation16–Citation19]. This is worrisome, because the use of suboptimal statistical methods in trial-based economic evaluations reduces their credibility and usefulness to decision-makers [Citation20], and may even lead to biased health-care decisions and, consequently, a possible waste of already scarce resources.

A possible means to improve the statistical quality of trial-based economic evaluations is to include clearly formulated recommendations on the statistical analysis of such studies in national pharmacoeconomic guidelines. However, the extent to which pharmacoeconomic guidelines currently provide guidance on what statistical methods to use in trial-based economic evaluations is unknown. Therefore, this study aimed to review existing national pharmacoeconomic guidelines to assess what recommendations are made regarding the statistical analysis of trial-based economic evaluations.

2. Methods

A scoping review of existing national pharmacoeconomic guidelines was conducted to assess what these guidelines currently recommend regarding the statistical analyses of trial-based economic evaluations.

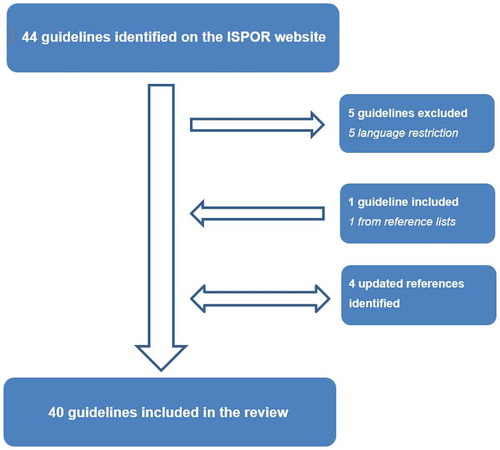

To identify existing guidelines, ISPOR’s ‘Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines Around the World’ website was searched up until February 20th, 2019 (https://tools.ispor.org/peguidelines/). This website aims to provide an overview of all available national pharmacoeconomic guidelines. In line with previous research, this website was considered to be the most comprehensive source of information because it is updated regularly with the help of health economic experts from about 60 countries [Citation5,Citation6,Citation8,Citation9]. Additionally, guidelines were identified by screening references of relevant review articles [Citation5,Citation6,Citation8,Citation9] and those of the included guidelines. Special efforts were made to identify the most recent versions of the included guidelines by searching websites of HTA agencies. If more than one guideline was available per country, the most recent guideline was included. Guidelines available in English, Dutch, Portuguese, German, Spanish, Persian, and Russian were included.

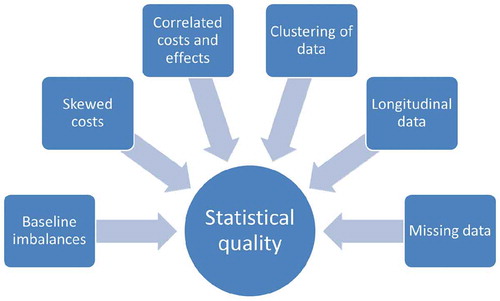

Data were extracted by one reviewer using a structured data extraction form, after which all of the extracted data were checked by a second reviewer (JvD, ME, AV, AGM, AJB, and MK participated in the data extraction process). Possible discrepancies between reviewers were discussed during a consensus-meeting. If only one reviewer was able to read and understand the guideline in question, a meeting was planned with a second reviewer. During these meetings, both reviewers went through the guideline together, with the second reviewer asking questions probing whether all required data were extracted and whether all extracted data were correct. Data were extracted on general guideline characteristics, such as language, organization, publication year, and type of guideline. In accordance with the ISPOR website, three types of guidelines were distinguished; (1) guidelines containing recommendations for economic evaluations that are not officially required to be followed for reimbursement (further referred to as ‘Recommendations’); (2) guidelines containing recommendations for economic evaluations that are required to be followed for reimbursement (further referred to as ‘Reimbursement guidelines’); and (3) guidelines concerning drug submission requirements with an economic evaluation part/section that are required to be followed for reimbursement (further referred to as ‘Drug submission guidelines’). For extracting the guidelines’ statistical recommendations, six issues were identified that typically complicate the statistical analysis of trial-based economic evaluations, including (1) baseline imbalances; (2) skewed costs; (3) correlated costs and effects; (4) clustering of data; (5) longitudinal data; and (6) missing data (). These statistical challenges were based on previous research [Citation1,Citation2,Citation16,Citation17,Citation19–Citation36] as well as our own experiences with analyzing trial-based economic evaluation data. A more detailed description of the statistical challenges is provided in .

All of the results were narratively synthesized and presented in a Table.

3. Results

3.1. Guidelines

In total, 40 national pharmacoeconomic guidelines were identified that met our inclusion criteria (). Of them, the majority was published in Europe (n = 22; 55%), followed by Asia (n = 6; 15%), North America and South America (both; n = 4; 10%), and Africa and Oceania (both; n = 2; 5%). Four guidelines were published prior to 2005 (10%), four guidelines were published between 2005 and 2009 (10%), 16 guidelines were published between 2010 and 2014 (40%), and 16 guidelines were published between 2015 and 2019 (40%). Many of the guidelines published after 2010 are updates of previous guidelines, rather than completely new guidelines. Most guidelines were published in English (n = 31; 78%) and by a public organization (n = 38; 95%), such as the English ‘NICE’, the Dutch ‘Health Care Institute’, the French ‘National Authority for Health’, and the Mexican ‘General Health Council’. Nine guidelines (23%) were categorized as ‘Recommendations’, meaning that they are not officially required to be followed for reimbursement; 22 guidelines (55%) were categorized as ‘Reimbursement guidelines’, meaning that they are required to be followed for reimbursement; and nine guidelines (23%) were categorized as being ‘Drug submission guidelines’, meaning that they are required to be followed as part of a drug submission ().

Box 1. Statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations.

Table 1. National pharmacoeconomic guidelines’ recommendations for dealing with the statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations.

3.2. Recommendations on how to deal with the statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations

3.2.1. Baseline imbalances

Four guidelines (10%) included recommendations on dealing with baseline imbalances (i.e., the Scottish, English, Swedish and Dutch guideline; see ). Of them, the Scottish guideline recommends to report baseline differences between groups, the English guideline recommends to adjust treatment effects for their baseline values, and the Swedish and Dutch guidelines recommend the use of regression techniques to adjust for baseline differences between groups. All other guidelines did not provide any recommendations on how to deal with baseline imbalances in trial-based economic evaluations.

3.2.2. Skewed costs

Five guidelines (13%) included recommendations on dealing with skewed costs (i.e., the Danish, Catalonian, Swedish, MERCOSUR, and Dutch guideline; see ). All of these guidelines recommend the use of non-parametric bootstrapping for estimating uncertainty, and the Dutch guideline added that the number of sampling draws should demonstrably lead to a stable result. All other guidelines did not provide any recommendations on how to deal with the skewed nature of cost data in trial-based economic evaluations.

3.2.3. Correlated costs and effects

None of the guidelines included recommendations on how to deal with correlated costs and effects in trial-based economic evaluations.

3.2.4. Clustering of data

None of the guidelines included recommendations on how to deal with the clustering of data in trial-based economic evaluations.

3.2.5. Longitudinal data

None of the guidelines included recommendations on how to deal with longitudinal data in trial-based economic evaluations.

3.2.6. Missing data

Seven guidelines (18%) included recommendations on dealing with missing data (i.e., the Australian, Belgian, New Zealand, Polish, Scottish, Swedish, and Dutch guideline; see ). The Australian, Belgian, Swedish, and Dutch guidelines recommend to explore and describe the possible missing data mechanism(s). The Swedish guideline added that missing data should never be assumed to occur completely at random. The Australian, Belgian, Polish, Scottish, and Dutch guidelines recommend to describe the applied imputation method. Furthermore, the New Zealand guideline discourages the use of last observation carried forward, and the Dutch guideline recommends to assess the robustness of the applied imputation method by performing sensitivity analyses with different imputation techniques. All other guidelines did not provide recommendations on how to deal with missing data in trial-based economic evaluations.

4. Expert opinion

National pharmacoeconomic guidelines were found to provide little to no guidance on how to deal with the statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations. That is, the majority of guidelines did not provide recommendations on how to deal with baseline imbalances, skewed costs, correlated costs and effects, the clustering of data, the longitudinal nature of data, and missing data in trial-based economic evaluations; and where recommendations were provided, they were very general in nature. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that, even though national pharmacoeconomic guidelines view transferability of, and dealing with patient heterogeneity in, economic evaluations as being important, very few of them proposed specific methods for dealing with these issues [Citation5,Citation77].

Various reasons may explain the lack of guidance by national pharmacoeconomic guidelines on how to deal with the statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations. First, the majority of guidelines was found to focus predominantly on model-based economic evaluations, and some even see model-based economic evaluations as the ‘gold standard’. The latter is evidenced by the French guideline that states that ‘modelling is the preferred approach in health economic evaluation’ [Citation78]. As a consequence, many guidelines only included detailed recommendations on how to construct a decision analytic model, but lacked guidance on how to appropriately analyze trial-based economic evaluations. Second, many of the identified guidelines seem to be modeled after, or included, reporting guidelines, such as the CHEC-list [Citation79], CHEERS statement [Citation80], or a self-developed one. The Belgian guideline, for example, included a checklist for assessing the quality of trial-based economic evaluations that mainly included reporting items, such as whether there was a comprehensive description of alternatives [Citation81,Citation82]. Even though reporting guidelines are important to ensure uniformity in the reporting of (trial-based) economic evaluations, they do not provide guidance on how to appropriately analyze such studies. Third, some guidelines were published over a decade ago, while in the meantime, methods for analyzing trial-based economic evaluations have improved considerably [Citation26]. Fourth, some guidelines only included very general statistical recommendations, instead of recommending specific methods for dealing with one or more of the statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations. The English guideline, for example, stated that “Data should be analyzed in a way that is methodologically sound and, in particular, minimizes any bias“, but did not indicate what those methodologically sound methods are. Guideline developers may have opted for such a strategy due to a lack of overall consensus on how to deal with statistical issues, such as skewed data and missing data, or in an effort to allow future analysts the freedom to choose different methods. It is unlikely, however, that such general recommendations will improve the quality of trial-based economic evaluations. In an effort to deal with this issue, the English guideline commissioned a series of Technical Support Documents with the aim of providing further information on how to implement the approaches described in the guideline. However, even though a broad range of Technical Support Documents is currently available, they are mostly focussed on the measurement and valuation of health and the conduct of modeling studies, and lack specific recommendations on how to statistically analyze trial-based economic evaluations [Citation83].

A possible limitation of this study is that we had to exclude five national pharmacoeconomic guidelines due to language restrictions (i.e., the Chinese, South Korean, Slovakian, Slovenian, and Czech guidelines). Nonetheless, with 40 guidelines, the number of included guidelines is relatively high compared to similar studies [Citation5,Citation77,Citation84] and we do not expect that the exclusion of some guidelines affected our overall conclusion. Also, as in previous reviews, there may have been some level of subjectivity in our assessment of what parts of the guidelines could be considered guidance and what not [Citation77]. We tried to tackle this limitation by using a structured data extraction form (available upon request) and by having all extracted data checked by a second reviewer. Another limitation might be that overall consensus does not exist regarding the most important statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations. Based on the literature as well as our own experiences with analyzing trial-based economic evaluation data, we selected the handling of baseline imbalances, skewed data, correlated costs and effects, clustering of data, longitudinal data, and missing data. Some researchers may be of the opinion that issues, such as sample size calculations and patient heterogeneity should have also been included. We decided to exclude sample size calculations because they are typically performed prior to the start of a clinical trial instead of during the analysis phase. Moreover, if studies are powered to detect relevant cost differences they will almost certainly be overpowered for the clinical outcome, while it may be unethical to continue recruiting patients into a trial beyond the point at which clinical superiority has been determined beyond reasonable doubt [Citation85]. Furthermore, the recommendations of national pharmacoeconomic guidelines regarding patient heterogeneity have already been assessed in a previous review, which found similar results [Citation77].

In order to improve the statistical quality of trial-based economic evaluations, we recommend to include more detailed guidance on how to statistically analyze such studies in national pharmacoeconomic guidelines. National guidelines may, for example, adopt and/or refer to the latest statistical recommendations of the ISPOR RCT-CEA Task Force and/or the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine[26; 84; 85]. The ISPOR RCT-CEA Task Force recommends to adjust for baseline imbalances using multivariable analyses, to deal with skewed costs using non-parametric bootstrapping, and to deal with missing data using multiple imputation. The task force also recommends to analyze multinational studies, in which participants are clustered within countries, using multilevel random effects models with shrinkage estimators. It remains unclear, however, whether this recommendation also applies to other kinds of clustered data (e.g. that of economic evaluations performed alongside a cluster-randomized controlled trial). If clinical endpoints are used in a trial-based economic evaluation, the task force recommends to use the statistical methods that are also applied in the clinical analysis, which are typically longitudinal in nature. However, the task force does not provide guidance on how to implement such longitudinal methods in trial-based economic evaluations. Recommendations on how to deal with correlated costs and effects are not included in the latest task force report [Citation26]. The latest Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine did not provide recommendations on how to deal with the statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations [Citation86], but did discuss the issues of skewed costs and missing data into more detail in their complete report [Citation87]. Also, if statistical recommendations are included, and/or referred to, in national pharmacoeconomic guidelines, it is important that these guidelines are updated frequently in order not to stifle further scientific development and/or restrict analysts to use outdated statistical methods.

Next to the inclusion of statistical recommendations in national pharmacoeconomic guidelines, other measures could also be taken to improve the statistical quality of trial-based economic evaluations. First, even though various methodological studies assessed the (relative) performance of certain statistical methods in trial-based economic evaluations (e.g. [Citation27–Citation34,Citation80]), more research into this area is warranted. Particular focus should be given to statistical methods for dealing with correlated costs and effects, clustered data, and longitudinal data as well as strategies for combining statistical methods, such as non-parametric bootstrapping and multiple imputation and/or longitudinal methods and multiple imputations. Second, increased research efforts should be focused on reaching consensus about the ‘best’ methods for dealing with the statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations. For achieving this, it might be useful to perform a scoping review to provide researchers with an overview of the (relative) performance of available statistical methods as well as existing gaps in knowledge. The results of such a scoping review may in turn serve as a starting point for the development of a consensus-based statistical quality checklist for trial-based economic evaluations.

In conclusion, current national pharmacoeconomic guidelines provide little to no guidance on what statistical methods to use in trial-based economic evaluations. Since the use of suboptimal statistical methods may lead to biased results, and, therefore, possibly to a waste of scarce resources, national agencies are advised to include statistical guidance and/or recommendations in their pharmacoeconomic guidelines.

Article Highlights

The statistical quality of many trial-based economic evaluations is poor.

When conducting trial-based economic evaluations, researchers often turn to national pharmacoeconomic guidelines for guidance.

Trial-based economic evaluations are typically characterized by one or more of the following six statistical challenges: 1) baseline imbalances; 2) skewed costs; 3) correlated costs and effects; 4) clustered data; 5) longitudinal data; missing data.

Current national pharmacoeconomic guidelines provide little to no guidance on how to deal with the statistical challenges to trial-based economic evaluations.

National agencies are advised to include more statistical guidance in their pharmacoeconomic guidelines.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford, UK: Oxford university press; 2015.

- Petrou S, Gray A. Economic evaluation alongside randomised controlled trials: design, conduct, analysis, and reporting. Bmj. 2011;342:d1548.

- Roseboom KJ, van Dongen JM, Tompa E, et al. Economic evaluations of health technologies in Dutch healthcare decision-making: a qualitative study of the current and potential use, barriers, and facilitators. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:89.

- Williams I, McIver S, Moore D, et al. The use of economic evaluations in NHS decision-making: a review and empirical investigation. SOUTHAMPTON. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12(7):iii, ix-x, 1–175.

- Barbieri M, Drummond M, Rutten F, et al. What do international pharmacoeconomic guidelines say about economic data transferability? Value Health. 2010;13:1028–1037.

- van Lier LI, Bosmans JE, van Hout HP, et al. Consensus-based cross-European recommendations for the identification, measurement and valuation of costs in health economic evaluations: a European Delphi study. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19(7):993-1008.

- Hjelmgren J, Berggren F, Andersson F. Health economic guidelines—similarities, differences and some implications. Value Health. 2001;4:225–250.

- Bracco A, Krol M. Economic evaluations in European reimbursement submission guidelines: current status and comparisons. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13:579–595.

- Action EJ, Heintz E, Gerber-Grote A, et al. Is there a European view on health economic evaluations? Results from a synopsis of methodological guidelines used in the EUnetHTA partner countries. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:59–76.

- Neumann PJ, Fang C-H, Cohen JT. 30 years of pharmaceutical cost-utility analyses. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:861–872.

- El Alili M, van Dongen JM, Huirne JA, et al. Reporting and analysis of trial-based cost-effectiveness evaluations in obstetrics and gynaecology. PharmacoEconomics. 2017;35:1007–1033.

- Neumann PJ, Greenberg D, Olchanski NV, et al. Growth and quality of the cost–utility literature, 1976–2001. Value Health. 2005;8:3–9.

- Vijgen SM, Opmeer BC, Mol BWJ. The methodological quality of economic evaluation studies in obstetrics and gynecology: a systematic review. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:253–260.

- Hoomans T, Evers SM, Ament AJ, et al. The methodological quality of economic evaluations of guideline implementation into clinical practice: a systematic review of empiric studies. Value Health. 2007;10:305–316.

- Hoomans T, Severens JL, van der Roer N, et al. Methodological quality of economic evaluations of new pharmaceuticals in the Netherlands. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:219–227.

- Gabrio A, Mason AJ, Baio G. Handling missing data in within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis: a review with future recommendations. PharmacoEconomics-open. 2017;1:79–97.

- Doshi JA, Glick HA, Polsky D. Analyses of cost data in economic evaluations conducted alongside randomized controlled trials. Value Health. 2006;9:334–340.

- Gomes M, Grieve R, Nixon R, et al. Statistical methods for cost-effectiveness analyses that use data from cluster randomized trials: a systematic review and checklist for critical appraisal. Med Decis Mak. 2012;32:209–220.

- Díaz-Ordaz K, Kenward MG, Cohen A, et al. Are missing data adequately handled in cluster randomised trials? A systematic review and guidelines. Clin Trial. 2014;11:590–600.

- Ramsey S, Willke R, Briggs A, et al. Good research practices for cost‐effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials: the ISPOR RCT‐CEA task force report. Value Health. 2005;8:521–533.

- Nixon RM, Thompson SG. Methods for incorporating covariate adjustment, subgroup analysis and between-centre differences into cost-effectiveness evaluations. Health Econ. 2005;14:1217–1229.

- Manca A, Hawkins N, Sculpher MJ. Estimating mean QALYs in trial‐based cost‐effectiveness analysis: the importance of controlling for baseline utility. Health Econ. 2005;14:487–496.

- Hoch JS, Briggs AH, Willan AR. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue: a framework for the marriage of health econometrics and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ. 2002;11:415–430.

- van Asselt AD, van Mastrigt GA, Dirksen CD, et al. How to deal with cost differences at baseline. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:519–528.

- van Dongen JM, van Wier MF, Tompa E, et al. Trial-based economic evaluations in occupational health: principles, methods, and recommendations. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56:563.

- Ramsey SD, Willke RJ, Glick H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials II—an ISPOR good research practices task force report. Value Health. 2015;18:161–172.

- Polsky D, Glick HA, Willke R, et al. Confidence intervals for cost–effectiveness ratios: a comparison of four methods. Health Econ. 1997;6:243–252.

- Willan AR, Briggs AH, Hoch JS. Regression methods for covariate adjustment and subgroup analysis for non‐censored cost‐effectiveness data. Health Econ. 2004;13:461–475.

- Glick H, Doshi J. Designing economic evaluations in clinical trials. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Bachmann MO, Fairall L, Clark A, et al. Methods for analyzing cost effectiveness data from cluster randomized trials. Cost Eff Resour Allocation. 2007;5:12.

- Gomes M, Grieve R, Nixon R, et al. Methods for covariate adjustment in cost‐effectiveness analysis that use cluster randomised trials. Health Econ. 2012;21:1101–1118.

- Grieve R, Nixon R, Thompson SG. Bayesian hierarchical models for cost-effectiveness analyses that use data from cluster randomized trials. Med Decis Mak. 2010;30:163–175.

- Ng ES, Diaz-Ordaz K, Grieve R, et al. Multilevel models for cost-effectiveness analyses that use cluster randomised trial data: an approach to model choice. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25:2036–2052.

- Lipsitz SR, Fitzmaurice GM, Ibrahim JG, et al. Joint generalized estimating equations for multivariate longitudinal binary outcomes with missing data: an application to acquired immune deficiency syndrome data. J R Stat Soc A Stat Soc. 2009;172:3–20.

- Noble SM, Hollingworth W, Tilling K. Missing data in trial based cost effectiveness analysis: the current state of play. Health Econ. 2012;21:187–200.

- Zhang Z. Missing data imputation: focusing on single imputation. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:9.

- Sekhon JS, Grieve RD. A matching method for improving covariate balance in cost effectiveness analyses. Health Econ. 2012;21:695–714.

- Twisk JW. Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology: a practical guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- van Leeuwen KM, Bosmans JE, Jansen AP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a chronic care model for frail older adults in primary care: economic evaluation alongside a stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(12):2494–2504.

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Guidelines for preparing submissions to the pharmaceutical benefits advisory committee. Version 5.0. Australian Government, Department of Health. 2016.

- Walter E, Zehetmayr S Guidelines on health economic evaluation–consensus paper. Inst Pharmaeconomic Res. 2006.

- Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia. Diretrizes metodológicas: diretriz de avaliação econômica. Ministério da Saúde Brasília, 2014.

- Behmane D, Lambot K, Irs A, et al. Baltic guideline for economic evaluation of pharmaceuticals (pharmacoeconomic analysis). The Baltics: Baltic Health Authorities; 2002.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs Technologies in Health. Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies. 4th ed. Canada. Ottawa (ON): The Agency; 2017.

- Castillo M, Castillo C, Loayza S, et al. Guía Metodológica Para La Evaluación Económica de Intervenciones En Salud En Chile. Subsecretaria de salud pública, Santiago, Chil: MINSAL; 2013.

- Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud. Manual para la elaboración de evaluaciones económicas en salud. Bogotá: IETS; 2014.

- Agency for Quality and Accreditation in Health Care, Department for development, research and health technology assessment: the Croatian guideline for health technology assessment process and reporting. Agency for Quality and Accreditation in Health Care, Zagreb (2011).

- Gálvez González AM. Guía metodológica para la evaluación económica en salud: Cuba, 2003. Rev Cub Salud Publica. 2004;30.

- Kristensen FB, Hørder M. Health technology assessment handbook. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Institute for Health Technology Assessment; 2008.

- Elsisi GH, Kaló Z, Eldessouki R, et al. Recommendations for reporting pharmacoeconomic evaluations in Egypt. Value Health Reg Issues. 2013;2:319–327.

- Pharmaceuticals Pricing Board, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Preparing a health economic evaluation to be attached to the application for reimbursement status and wholesale price for a medical product. 2017.

- Institute for Quality Efficiency in Health Care. General methods for the assessment of the relation of benefits to costs. Colgne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care; 2009.

- The National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition. Professional healthcare guideline on the methodology of health technology assessment. J Hung Pharm Authority Doctors Pharm. 2017;67(1):1–23.

- Cheraghali N, Dinarvand. Criteria for developing an economic evaluation file - 2017 to 2019. Iran FDA, Medicine selecting committee secretriate 2017.

- The National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics. Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health Technologies in Ireland 2018. Health Information and Quality Authority, 2018.

- Capri S, Ceci A, Terranova L, et al. Guidelines for economic evaluations in Italy: recommendations from the Italian group of pharmacoeconomic studies. Drug Inf J. 2001;35:189–201.

- Ministry of Health Pharmaceutical Administration. Guidelines for the submission of a request to include a pharmaceutical product in the national list of health services. 2010.

- Study team for “Establishing evaluation methods DS, and assessment systems toward the application of economic evaluation of healthcare technologies to governmental policies”. Guideline for Preparing Cost-Effectiveness Evaluation to the Central Social Insurance Medical Council. 2016.

- Ministry of Health Malaysia - Pharmaceutical Services Devision. Pharmacoeconomic guideline for Malaysia. 2012.

- de Salubridad General C Guía para la conducción de estudios de evaluación económica para la actualización del Cuadro Básico de Insumos del Sector Salud en México. Dirección General Adjunta de Priorización Comisión interinstitucional del Cuadro Básico de Insumos del Sector Salud. 2008.

- Common Market of the Southern Cone (MERCOSUR). Guía Para Estudios De Evaluación Económica De Tecnologías Sanitarias/Guideline For Economic Evaluation Of Health Technologies. 2015.

- PHARMAC (Pharmaceutical Management Agency). Prescription for pharmacoeconomic analysis: methods for cost-utility analysis (v 2.2), 2015.

- The Norwegian Medicines Agency. Guidelines on how to conduct pharmacoeconomic analyses. 2012.

- The Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System. Health technology assessment guidelines version 3.0. 2016.

- Da Silva EA, Pinto C, Sampaio C, et al. Guidelines for economic drug evaluation studies. Lisbon, Portugal: INFARMED. 1998.

- Center for Healthcare Quality Assessment and Control of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Guidelines for conducting a comparative clinical and economic evaluation of drugs. 2016.

- Scottish Medicines Consortium. Guidance to manufacturers for completion of new product assessment form (NPAF). 2014.

- Department of Health. Republic of South Africa. Guidelines for pharmacoeconomic submissions. Government Gazette. 2012.

- López-Bastida J, Oliva J, Antonanzas F, et al. Spanish recommendations on economic evaluation of health technologies. Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11:513–520.

- Puig-Junoy J, Oliva-Moreno J, Trapero-Bertran M, et al. Guía y recomendaciones para la realización y presentación de evaluaciones económicas y análisis de impacto presupuestario de medicamentos en el ámbito del CatSalut. Barcelona: Servei Català de la Salut (CatSalut); 2014.

- Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment; Assessment of Social Services. Assessment of methods in health care–a handbook. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment; Assessment of Social Services. 2016.

- Bundesamt für Gesunheid BAG. Operationalisation of the terms effectiveness, expediency and profitability of pharmaceuticals. 2011.

- Taiwan Society for Pharmacoeconomic Outcomes Research. Guidelines of methodological standards for pharmacoeconomic evaluations. 2006.

- Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health.Guidelines for health technology assessment in Thailand (Second edition). J Med Assoc Thailand. 97(Suppl(5)):2014:S1-S134.

- Zorginstituut Nederland. Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare. 2016.

- Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. The AMCP format for formulary submissions. Version 4.0.

- Ramaekers BL, Joore MA, Grutters JP. How should we deal with patient heterogeneity in economic evaluation: a systematic review of national pharmacoeconomic guidelines. Value Health. 2013;16:855–862.

- Department of Economics and Public Health Assessment. Choices in methods for economic evaluation. Paris, France: Public Health Assessment Haute Autorité de Santé; 2012.

- Evers S, Goossens M, De Vet H, et al. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on health economic criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:240–245.

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS)—explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR health economic evaluation publication guidelines good reporting practices task force. Value Health. 2013;16:231–250.

- Drummond M, Jefferson T. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. Bmj. 1996;313:275–283.

- Cleemput I, Neyt M, Van de Sande S, et al. Belgian guidelines for economic evaluations and budget impact analyses. Health Technology Assessment (HTA) KCE Report C. 183. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE); 2012.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. 2013.

- Knies S, Severens JL, Ament AJ, et al. The transferability of valuing lost productivity across jurisdictions. Differences between national pharmacoeconomic guidelines. Value Health. 2010;13:519–527.

- Briggs A. Economic evaluation and clinical trials: size matters: the need for greater power in cost analyses poses an ethical dilemma. BMJ. 2000;321(7273):1362–1363.

- Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses. Second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Jama. 2016;316(10):1093–1103.

- Neumann PJ, Sanders GD, Russell LB, et al. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2016.