ABSTRACT

Objective: Pneumococcal diseases including invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), pneumonia, and acute otitis media (AOM) impose a substantial public health burden. This study performed a budget impact analysis of the use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) in the National Immunization Program (NIP) in Colombia.

Methods: We compared the direct medical cost of the scenario without and with PCV vaccination using either pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) or 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) over 5 years (2020–2024) from the health-care system perspective. Vaccine efficacy estimates were obtained from published sources and vaccine prices were taken from the Pan-American Health Organization Revolving Fund. Vaccine coverage was assumed to be 90% based on Colombia data.

Results: Using PHiD-CV in the NIP in Colombia would reduce the estimated cost for treating pneumococcal disease by US$46.1 m over the 2020–2024 period (US$40.2 m using PCV-13), with a budget impact of US$100.1 m for PHiD-CV (US$121.4 m for PCV-13), and would cost US$3.1 m less per year on vaccine doses than using PCV-13.

Conclusion: These findings are potentially valuable for the selection of vaccines for their national immunization programs under conditions of budgetary constraint.

1. Introduction

1.1. Pneumococcal disease

Infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae can result in a range of illnesses including invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), pneumonia, and acute otitis media (AOM). Such pneumococcal disease represents a substantial public health burden in children aged <5 years worldwide [Citation1,Citation2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends inclusion of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) in national childhood immunization programs [Citation3].

Two PCVs are available in Latin America and are routinely used in national immunization programs (NIPs): pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV, Synflorix, GSK) and a 13-valent PCV (PCV-13, Prevnar 13, Pfizer) was introduced into the NIP in Colombia in 2012 [Citation4,Citation5]. Since its introduction, reductions in the burden of pneumococcal disease have been reported. It has been estimated that 1,624 IPD cases have been prevented annually since vaccine introduction, as well as 15,988 cases of all-cause pneumonia and 230,140 cases of AOM. Vaccination has also been estimated to have saved more than US$43 million per year in direct medical costs [Citation6].

Recent studies from the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), Johns Hopkins University’s International Vaccine Access Center (IVAC), and the WHO have reported no evidence of a different net impact on overall pneumococcal disease burden between PHiD-CV and PCV-13 [Citation3,Citation7–9]. Both PCVs have a substantial impact on pneumonia, vaccine-type IPD, and carriage [Citation3,Citation7–9].

1.2. Economic analysis of PCVs in Colombia

Many studies have evaluated the costs and benefits of PCVs and have indicated that these vaccines are cost-effective compared to the no vaccination strategy in Colombia [Citation10–13]. Budget impact analysis (BIA) addresses the question of affordability by estimating the financial impact on annual healthcare resource use and costs for the first and subsequent years following vaccine introduction [Citation14]. This is especially important in situations with health-care budget constraints when resources are available for only a limited number of interventions.

1.3. Objective

Although the latest systematic reviews consider that there is no superiority of one PCV over the other against IPD and pneumonia, we hypothesize that they may differ in terms of their economic and financial value. In the present study, we aimed to perform a BIA of vaccinating children aged <5 years with each of the PCVs over the next 5 years (2020 to 2024), from the perspective of the health system in Colombia. The objective of this BIA is to explore the health and economic consequences of the choice of PCV to be used in the NIP in Colombia, in order to plan for the required resources and consider possible uncertainty.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Structure

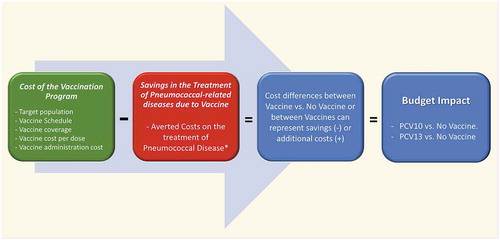

We used a Microsoft Excel-based cost calculator, as recommended in BIA guidelines, to estimate the budget impact of PCV in the NIP in Colombia [Citation15]. We compared direct medical costs of the base-case scenario (no vaccine) and direct medical costs of vaccination scenarios with PHiD-CV or PCV-13. The budget impact of each vaccination scenario was calculated as the cost difference with the base-case scenario ().

Figure 1. Model Schematics

2.2. Assessed Strategies & target population

The time horizon of the analysis was five years (2020–2024), and the cost perspective was that of the health-care system of Colombia. The 5-year time horizon was selected to show the direct effect of the PCVs in the NIP on costs and outcomes. As PHiD-CV was introduced in 2012 in the NIP, we assumed that vaccine effects would have reached steady-state by the time of the analysis (2020–2024).

We considered pneumococcal disease in children aged 0 to 4 years, being the population with the highest disease burden, and we estimated the annual direct medical costs of treating patients with the following pneumococcal disease outcomes: IPD (pneumococcal meningitis and pneumococcal bacteremia); hospitalized all-cause pneumonia; ambulatory all-cause pneumonia; and all-cause AOM. Treatment costs associated with pneumococcal disease were projected to be reduced in the vaccination scenarios, compared with the base-case, based on previously demonstrated vaccine efficacy/effectiveness [Citation3,Citation7–9,Citation16–19]. Herd immunity was not considered in the analysis as we focused on vaccine short-term effects and adverse events were also not included as we consider them negligible in this setting. In addition to a reduction on pneumococcal cases and treatment costs, vaccination scenarios also included the cost of the vaccine doses and the vaccine administration. Two vaccination scenarios were analyzed comparing the use of PHiD-CV and PCV-13 in the NIP of Colombia (high vaccine coverage in the NIP), where PCVs are provided free of charge to children under 5 years of age, in a 2 + 1 schedule with doses administered at 2, 4 and 12 months of age [Citation20]. Treatment cost of pneumococcal disease is covered by the General Social Security Health System (GSSHS) in Colombia, which has two main plans, contributory and subsidized; the contributory regime covers salaried workers, pensioners, and independent workers, whereas the subsidized plan covers anyone who cannot pay [Citation21]. Healthcare system perspective was used for the analysis to mimic the perspective of the GSSHS. The impact of these interventions on productivity, social services, and other costs outside the healthcare system were not included because these aspects are not generally relevant to the health-care budget holders in Colombia.

The target population for the analysis was the birth cohort of Colombia each year between 2020 and 2024. Population projection data for Colombia by age for these years from the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) were used in the analysis, as shown in [Citation22].

Table 1. Parameters and ranges used for the budget impact and sensitivity analysis of PCVs in Colombia

2.3. Parameters for the base-case scenario (no vaccine)

Probabilities of each pneumococcal disease (without PCV in the NIP), were obtained from a previous cost-effectiveness analysis requested by the Ministry of Health of Colombia for the introduction of PHiD-CV in the NIP, in order to use input data relevant to health-care budget holders in Colombia [Citation10]. IPD and AOM sequelae were not considered in the current analysis as we focused on short-term consequence of the vaccination program and also because the cost-effectiveness study we used to obtain epidemiological data have not reported or considered them [Citation10]. The annual probability of each episode (pneumococcal meningitis, ambulatory all-cause pneumonia, hospitalized all-cause pneumonia, and all-cause AOM) reported before vaccine introduction between 0 and 4 years of age () was multiplied by the number of years of follow-up (5 years for this analysis) and the birth cohort each year to estimate the pneumococcal disease burden with no vaccine introduction in the base-case analysis (). The result obtained was compared with and validated against the original publication. As the probability of pneumococcal bacteremia was not reported in the original study, we assumed this probability to be 4 times the probability of pneumococcal meningitis, based on the study of Benavides et al., 2012, for Colombia [Citation10,Citation23] (). The baseline incidence of AOM reported in this reference study was considered higher than other comparable studies, and therefore we used a lower incidence of AOM in additional scenarios [Citation10,Citation11].

As the costing data reported in the cost-effectiveness study of Castañeda-Orjuela et al., 2012 were not originally developed for Colombia but for a low-income country using a societal perspective, we decided to use the cost of medical treatments for Colombia reported by Marti et al., 2013 [Citation10,Citation11]. This study developed the costs of treating the different outcomes associated with pneumococcal disease using a micro-costing technique, specifically considering the healthcare system of Colombia. The original costs reported for 2008 (similar to those reported by Castañeda-Orjuela et al., 2012) were updated to December 2018 using the Consumer Price Index (IPC) for Colombia (Historic Annual IPC, Department of National Statistics (DANE), Colombia) and the historical exchange rate between the US dollar (US$) and Colombian peso (3,247 Colombian pesos per US$ on 31 December 2018) from the XE web page [Citation10,Citation24,Citation25] (). No discounting was applied for the cost estimates, according to the principles of BIA [Citation14,Citation15].

2.4. Parameters for the vaccination scenarios

The total cost of the Colombian NIP in 2009 was reported to be US$ 107.8 million by Castañeda-Orjuela et al., 2013 [Citation26]. The Central Level of the Ministry of Health spent US$54.9 million on vaccine doses for the NIP and US$11.2 million in administration costs (20.37% increment over the cost of vaccine doses), including supplies, personnel, cold chain, vehicles and transportation, buildings and other costs such as social mobilization, operating costs, and supervision. The cost PCV wastage was estimated to be 2% for Colombia and it was included in the administration cost of the analysis [Citation26]. We assumed the same incremental percentage for administration costs (20.37%) in the vaccination scenarios and a range of ± 20% for sensitivity analysis purposes, as shown in [Citation26]. This absolute value of administration cost was assumed to be equal for both PCVs in the analysis.

Vaccine prices per dose published by the PAHO Revolving Fund for 2019 were used in the analysis, as this is the regular vaccine source for the NIP of Colombia [Citation27]. The vaccine price per dose of PHiD-CV and PCV-13 was US$12.85 and US$14.50, respectively (). Since the NIP of Colombia maintains a high vaccine coverage (>90% in 2018) since its introduction, we decided to use a constant 90% coverage for all years analyzed with a range between 80%-100% used in sensitivity analysis ()[Citation20]. The total cost of vaccination with PHiD-CV or PCV-13 was estimated based on the annual target population, the recommended 2 + 1 vaccine schedule for Colombia, the vaccine cost per dose, the estimated vaccine coverage in the target population and the cost of vaccine administration ().

In order to estimate the changes in the use of pneumococcal-related health-care services after PCV introduction in the NIP, we used different reviews developed by recognized independent institutions to estimate vaccine effects on medical treatment costs averted [Citation3,Citation7–9]. According to the IVAC at Johns Hopkins University, PAHO, and WHO there is at present no evidence of a difference between PHiD-CV and PCV-13 in their net impact on overall pneumococcal disease burden (IPD & all-cause pneumonia) [Citation3,Citation7–9]. Both PCVs have a substantial impact against pneumonia, vaccine-type IPD, and carriage [Citation3,Citation7–9]. Therefore, we used equal effects for both PCVs against IPD, hospitalized pneumonia, and ambulatory pneumonia in our analysis, based on these reviews [Citation3,Citation7–9]. We considered a steady-state scenario for the analysis because PHiD-CV was introduced into the NIP several years ago, and therefore full vaccine effects were assumed during all the years of the analysis. Consequently, we simulated the effect of PCVs against all-type IPD using one unique effectiveness study where the PCVs effects were compared [Citation16]. This was an observational case–control study that showed non-significant differences between vaccines effects against all-type IPD. A 70.0% reduction in IPD cases was used in our analysis, based on the average vaccine effectiveness reported for both vaccines (PHiD-CV and PCV-13), and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was also used for sensitivity analysis () [Citation16]. PCVs effects against all-cause pneumonia was simulated based on the results of a Latin American clinical trial of PHiD-CV [Citation17]. Vaccine effect against hospitalized all-cause pneumonia was set at 23.4%, and against all-cause ambulatory pneumonia it was 7.3% (). In line with the IVAC, PAHO, and WHO reviews, the VE against all-cause pneumonia was assumed to be equal for both PCVs [Citation3,Citation7–9]. This is also aligned with the results of a previous Cochrane Collaboration review, which showed no relationship between the efficacy of different PCVs against pneumonia and the number of serotypes contained [Citation18]. Finally, we estimated different effects between PCVs against AOM, based on different clinical trial results for the two vaccines [Citation17,Citation19]. The effect of PHiD-CV against all-cause AOM was taken from Tregnaghi et al., 2014 (19.0%), and the effect of PCV-13 against all-cause AOM was based on the results reported for the PCV-7 clinical trial by Black et al., 2000 and later adjusted to 13.0% for the additional pneumococcal type coverage of PCV-13 by Castañeda-Orjuela et al., 2018 () [Citation13,Citation17,Citation19]. Equal vaccine effects against AOM were also explored in additional scenarios. The vaccine effect described were used to estimate the number of pneumococcal cases averted and medical costs averted by each vaccine, as a result of reductions in the number of medical visits, hospitalizations and treatments associated with pneumococcal disease ().

2.5. Budget impact analysis

The budget impact of PCVs in the NIP of Colombia was estimated by comparing the direct medical cost of the base-case scenario (no vaccine) and the vaccination scenarios for both PCVs annually over a 5-year period (2020–2024). The budget impact for each PCV was calculated based on the incremental costs of acquiring and administering each PCV, minus the medical costs averted by each vaccine via the reduction of medical visits, hospitalizations, and treatments associated with pneumococcal disease (). The expenses of vaccine acquisition and administration are partially offset by reduced use of current medical interventions for pneumococcal disease in the healthcare system of Colombia.

2.6. Sensitivity analysis

To assess the effect of uncertainties around the BIA results, univariate sensitivity analysis was conducted using the lower and upper limits of the value ranges for each parameter as shown in .

3. Results

3.1. Vaccine effects on the cost of pneumococcal disease

We estimated that the use of PHiD-CV in the NIP would reduce the costs associated with pneumococcal disease treatments by ~US$9.2 million per year, or US$ 46.1 million in the 5-year study period, compared with the no vaccination base-case scenario (). Averted treatment costs related to hospitalized pneumonia (44%) and AOM (40%) accounted for 84% of the projected savings. If PCV-13 were used instead of PHiD-CV, the savings in costs associated with pneumococcal disease would be lower (US$40.2 million) in the 5-year period (US$5.8 million lower than with PHiD-CV).

Table 2. Cases and treatment costs of pneumococcal disease, without and with PHiD-CV introduction in Colombia

3.2. Cost of the PCV program

We also estimated that the cumulative annual cost for the universal vaccination program in the NIP of Colombia with the PHiD-CV totaled US$29.2 million (US$146.1 over the 5-year period), whereas the cumulative annual cost for PCV-13 totaled US$32.3 million (US$161.7 over the 5-year period). The use of PHiD-CV thus generates cost savings of over US$3.1 million per year for the NIP of Colombia, compared with PCV-13 ().

Table 3. Comparing the budget impact of higher-valent PCVs by year using the 2019 PAHO Revolving Fund prices

3.3. Budget impact analysis and additional scenarios

Finally, the estimated budget impact of PHiD-CV in the 5-year period analyzed was US$100.1 million (approximately US$20.0 million per year), and the estimated budget impact of PCV-13 in the 5-year period was US$121.4 million (US$318.8 m minus US$197.3 m = US$121.5 m), or approximately US$24.3 million per year. The incremental budget impact estimated for PCV-13 in comparison with PHiD-CV would be an additional US$21.4 million in the 5-year period ().

shows the results for different scenarios of vaccine coverage (80% or 100%), equal effects between PCVs against AOM (PCV-13 with similar efficacy than PHiD-CV in the main analysis, or PHiD-CV with similar efficacy than PCV-13 in the main analysis), and a reduced incidence of AOM. If vaccine coverage were modified to 80% or 100%, the 5-year budget impact of PHiD-CV varied between US$83.8 million to US$116.3 million, and for PCV-13 from US$103.5 million to US$139.4 million. In a scenario where PCV-13 has the same effects on AOM as PHiD-CV, the budget impact estimated for PCV-13 would be US$115.6 million in the 5-year period, and in a scenario where PHiD-CV has the same effects on AOM as PCV-13, the budget impact estimated for PHiD-CV would be US$105.9 million in the 5-year period. Therefore, even with equal effects against AOM, the difference in budget impact would favor PHiD-CV by US$15.6 million compared with PCV-13. Finally, in the scenario with a reduction on the incidence of AOM, (half of the annual probability reported [Citation10]) the budget impact would favor PHiD-CV by US$18.5 million ().

Table 4. Effects of different coverage, efficacy against AOM and AOM incidence scenarios on vaccination cost and budget impact of both higher-valent PCVs over 5 years, using the 2019 PAHO Revolving Fund vaccine prices per dose

3.4. Sensitivity analysis

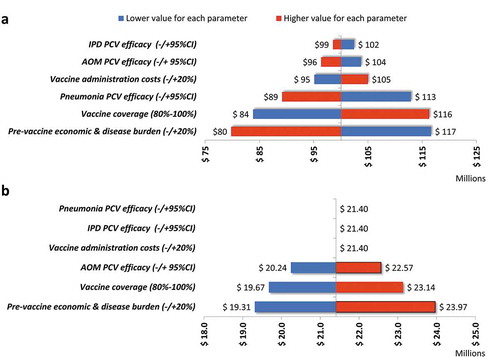

In order to explore the effect of uncertainty around the input parameters used on the estimated budget impact of PCVs in Colombia or the differences between the vaccines, we conducted a univariate sensitivity analysis using the ranges described in . presents these results and shows that the estimated budget impact of PHiD-CV over the 5-year period of US$100.1 million could range between US$79.8 million and US$116.6 million () due to parameter uncertainty within the ranges analyzed. The most significant drivers for variations were vaccine coverage, vaccine efficacy against pneumonia and the estimated pre-vaccine pneumococcal disease and economic burden.

Figure 2. Sensitivity analysis of the budget impact of PCVs in Colombia: (a) Budget impact of PHiD-CV vs no vaccination; (b) Budget impact of PCV-13 vs PHiD-CV. AOM, acute otitis media; CI, confidence interval; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

Similarly, indicates that the estimated excess budget impact for PCV-13 compared with PHiD-CV (over the 5-year period) of US$21.4 million would show only minor changes as a result of parameter uncertainty, varying within a range of US$19.3–24.0 million. PCV efficacy against pneumonia or IPD and vaccine administration costs did not influence the result, because these parameters were considered equal for both vaccines in the analysis. PCV efficacy against AOM, vaccine coverage and the estimated pre-vaccine pneumococcal disease and economic burden had only minor effects on the results obtained.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary findings

While PCVs are cost-effective in Colombia based on published evidence, many Latin American countries including Colombia have difficulties with vaccine affordability, with no reliable and sustainable financing, which affects the primary goals of the NIP. In the present scenario, this BIA was performed to assess the affordability and comparability of the adoption of PCVs in Colombia [Citation10–13].

The current analysis shows that the maintenance of PHiD-CV in the NIP (used since 2012) would reduce the projected costs associated with pneumococcal disease by US$46.1 million in the 5-year study period, mostly related to hospitalized pneumonia and AOM treatment costs. These health and economic effects would require the investment of US$146.1 million in the 5-year study period (2020–2024), to maintain PHiD-CV in the NIP of Colombia. Therefore, the estimated budget impact of the use of PHiD-CV over the 5-year period in Colombia was US$100.1 million. Sensitivity analysis showed that the 5-year budget impact for PHiD-CV could vary between US$79.8–116.6 million due to parameter uncertainty. The most significant drivers for the variation were vaccine coverage, PCV efficacy against pneumonia and the estimated pre-vaccine pneumococcal disease and economic burden.

When comparing the two PCVs, PHiD-CV is associated with greater savings compared to a potential use of PCV-13. The incremental budget impact estimated for PCV-13 in comparison with PHiD-CV would be an additional US$21.4 million over the 5-year period. Analysis of different scenarios indicated that even with equal effects against AOM for both vaccines, the difference in budget impact would favor PHiD-CV over PCV-13 by US$15.5 million. Sensitivity analysis on the incremental budget impact estimated for PCV-13 indicated that the reported excess budget impact for PCV-13 would have only minor variations (approximately US$4.7 million per year) due to parameter uncertainty, ranging between US$19.3 million and US$24.0 million. Efficacy against AOM, vaccine coverage and the estimated pre-vaccine pneumococcal disease and economic burden would have only minor influence. This incremental budget could be more effectively used for other health interventions, such as improving vaccine coverage in remote areas or preventive interventions against other diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), dengue, or malaria, that may offer greater public health benefits than switching to a different PCV [Citation28–31].

4.2. Strengths

We used a conservative approach to estimate the effects of PCVs, by preferring efficacy data over effectiveness data and by not considering potential herd effects of vaccines and sequelae. Instead of using a complex dynamic transmission model, we have used a simple cost calculator developed in Microsoft Excel, because this offers transparency and is more easily understood by budget holders, as recommended in BIA guidelines [Citation15]. We have also used the same estimates of pre-vaccine disease burden and direct medical treatment costs per case described in the cost-effectiveness requested by the Ministry of Health of Colombia for PCV introduction, in order to simulate scenarios and assumptions of interest for the decision-makers of the country [Citation10,Citation11,Citation13]. Our assumptions on vaccine effects were based on the conclusions of systematic literature reviews performed by well recognized international organizations like PAHO, IVAC, and WHO, in order to include the latest consensus on these interventions [Citation3,Citation7–9]. Finally, our analysis considers the PCV effects on the overall pneumococcal outcomes, without limiting the analysis on their effect on IPD or even worst, considering only IPD related to a few pneumococcal types.

4.3. Limitations

Our analysis is a simplification of the epidemiology of pneumococcal disease and the effect of the PCV introduction. We used a static approach and did not capture completely pneumococcal disease transmission dynamics, and the real-world effect of vaccination on unvaccinated adults of Colombia. However, quantifying such dynamics requires scientific data not currently available for Colombia. Therefore, we did not consider all the potential effects of PCVs in the analysis. Our assumptions of the effects of PCV for the analysis are based on the recommendations of international organizations, clinical trial results of PCVs, and the scenarios used in the cost effectiveness study requested by the Ministry of Health of Colombia for PCV introduction, but not on real-world evidence of these effects in Colombia. We could have used the herd effects described for PCVs in different countries but under no head-to-head comparison any single scenario selected for the comparison of vaccine indirect effects in Colombia would significantly bias the budget impact results. Finally, the investment required for vaccine introduction, distribution and administration is under the account of the NIP of Colombia, but the saving reported on pneumococcal treatments averted by vaccination are influencing accounts of the General Social Security Health System (GSSHS) of Colombia. Therefore, our budget impact analysis is useful for a more general view of the public health system financing and not directly to the NIP of Colombia.

4.4. Our results in the Colombian context

The total Colombian government health expenditure in 2017 was approximately US$10,000 million, and the government is reporting an 8.12% increase for 2020 [Citation32,Citation33]. The health expenditure on the NIP (100% government funded) has doubled since 2007, reaching US$93 million in 2017 (US$129 per infant) [Citation34]. Our estimation is that ~30% (US$30 million of US$93 million) of the expenditure on the NIP of Colombia is related to PCV immunization. Our analysis shows that PHiD-CV introduction into the NIP has had a large impact on the health system, averting an average of 1,225 IPD cases, 7,200 pneumonia cases, and 120,000 AOM cases per year in the population of Colombia.

Colombia has a very comprehensive NIP that accounts for only a very small part (less than 1%) of government healthcare spending. During periods of financial crisis, the NIP remains highly vulnerable to budget cuts, because immunizations are administered to healthy individuals (who are thus not seeking a cure), and whereas vaccine costs are incurred immediately, vaccine benefits are not necessarily observable in the short term [Citation35,Citation36]. In contrast, we think that the investment in vaccines should be considered in view of the disease burden prevented and the far-reaching public health benefits of population-wide vaccination (i.e. a healthier population contributing to a healthier economy) [Citation37]. Policymakers should thus balance investment in vaccines against the far-reaching benefits of vaccination, which protects the entire population and economy against potentially troublesome and resource-intensive outbreaks and prevents the resurgence of infectious diseases [Citation38]. Confronted with budget restrictions, policymakers may be tempted to seek immediate economic savings. However, to sustain universal health-care systems, policymakers should carefully consider the broader interactions among economic, social, and political sustainability issues [Citation39].

5. Conclusion

PHiD-CV vaccination in Colombia is associated with projected savings of US$46.1 million in pneumococcal disease costs for an investment of US$146.1 million on vaccination, with an estimated net budget impact of US$100.1 million over 5 years. Maintaining PHiD-CV in the NIP generates greater savings (US$ 4.3 million per year) than the potential use of PCV-13. PHiD-CV vaccination absorbs a relatively low portion of national healthcare spending relative to its substantial benefits for the population in Colombia, which extend well beyond individual health and benefit the entire population and society, and thus represents a wise investment. In a constrained budgetary context, vaccination programs should be preserved or even strengthened to sustain the population’s health and to avoid longer-term health problems and costs.

6. Expert commentary

Both PCVs are very cost effective for Colombia and their reported ICERs are non-significantly different (10-13). In this context, the present study demonstrates that maintaining PHiD-CV in the NIP is cost saving compared with switching for PCV-13. The health and economic impact of the PCV vaccination in the Colombian context is enormous. These results are relevant for periods of financial crisis, where the NIP remains highly vulnerable to budget cuts, because immunizations are administered to healthy individuals (not seeking a cure), with costs incurred immediately and benefits not easily identifiable when appropriate surveillance systems are not available. The savings we have estimated are based on the different cost per dose of both vaccines in the PAHO Revolving Fund and the differential effects consider against AOM. Our assumptions of the effects of PCV are based mainly on the recommendations of international organizations (PAHO, IVAC, WHO) but not on real-world evidence of these vaccines for Colombia (3, 7-9). Perhaps, health authorities have to consider and plan adequate surveillance systems when new vaccines are introduced, so that their effect can be evaluated later with robust data. Future studies using real world data should be helpful to improve the evaluation of these vaccines for Colombia.

Declaration of interest

Jorge Gomez*, Luz Elena Moreno, Dagna Constenla, Diana Caceres and Edisson Rodriguez are employees of GSK group of companies. Jorge Gomez; Luz Elena Moreno and Diana Caceres holds shares in GSK group of companies. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewers Disclosure

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally on the manuscript conceptualization, methodology, analysis, data curation, writing review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (169.7 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Business & Decision Life Sciences platform (on behalf of GSK) for editorial assistance, manuscript coordination and writing support. Pierre-Paul Prevot coordinated the manuscript development and editorial support. Carole Nadin (Fleetwith Ltd, on behalf of GSK) provided editorial support.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

References

- O’Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, et al. 2009. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 374(9693):893–902.

- Wahl B, O’Brien KL, Greenbaum A, et al. 2018. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000-15. Lancet Glob Health. 6(7):e744–e57.

- Organization WH. 2019. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in infants and children under 5 years of age: WHO position paper – february 2019. Weekly Epidemiological Rec. 94(8):85–104.

- de Oliveira LH, Trumbo SP, Ruiz Matus C, et al. 2016. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction in Latin America and the Caribbean: progress and lessons learned. Expert Rev Vaccines. 15(10):1295–1304.

- Caceres DC, Ortega-Barria E, Nieto J, et al. 2018. Pneumococcal meningitis trends after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction in Colombia: an interrupted time-series analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 14(5):1230–1233.

- Caceres DC, deAntonio R, Nieto J, et al. Estimated annual impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) immunization program in Colombia (2011-2018). Value Health Regional Issues. 2019;19:S43.

- Cohen O, Knoll M, O’Brien K, et al.Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) Product Assessment (2017) [ Accessed 2017Sept29]; Available from: https://www.jhsph.edu/ivac/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/pcv-product-assessment-april-25-2017.pdf.

- de Oliveira LH, Camacho LA, Coutinho ES, et al., 2016. Impact and Effectiveness of 10 and 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines on Hospitalization and Mortality in Children Aged Less than 5 Years in Latin American Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 11(12): e0166736.

- Organization WH. Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on immunization, October 2017 – conclusions and recommendations. Weekly Epidemiological Rec. 2017;92:729–748.

- Castaneda-Orjuela C, Alvis-Guzman N, Velandia-Gonzalez M, et al., 2012. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines of 7, 10, and 13 valences in Colombian children. Vaccine. 30(11): 1936–1943.

- Marti SG, Colantonio L, Bardach A, et al. 2013. A cost-effectiveness analysis of a 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children in six Latin American countries. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 11(1):21.

- Ordonez JE, Orozco JJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the available pneumococcal conjugated vaccines for children under five years in Colombia. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2015;13(1):6.

- Castaneda-Orjuela C, De la Hoz-restrepo F. 2018. How cost effective is switching universal vaccination from PCV10 to PCV13? A case study from a developing country. Vaccine. 36(38):5766–5773.

- Garay OU, Caporale JE, Pichon-Riviere A, et al. [Budgetary impact analysis in health: update with a model using a generic approach]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2011;28(3):540–547.

- Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. 2014. Budget impact analysis-principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health. 17(1):5–14.

- Deceuninck G, De Serres G, Boulianne N, et al. 2015. Effectiveness of three pneumococcal conjugate vaccines to prevent invasive pneumococcal disease in Quebec, Canada. Vaccine. 33(23):2684–2689.

- Tregnaghi MW, Saez-Llorens X, Lopez P, et al. 2014. Efficacy of pneumococcal non typable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) in young Latin American children: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 11(6):e1001657.

- Lucero MG, Dulalia VE, Nillos LT, et al. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease and X-ray defined pneumonia in children less than two years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD004977.

- Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, et al. 2000. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 19(3):187–195.

- Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO). PAHO. Pneumococcal Conjugated Vaccine Coverage in Colombia, 2017 (2017) [ Accessed 2020Jul23]; Available from: http://ais.paho.org/imm/IM_JRF_COVERAGE.asp.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (Colombia). Aseguramiento al Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud. Bogotá: MSPS (2014) [ Accessed 2019Nov28]

- ECLAC: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Population database. The 2017 revision. Based on Projections 2015–2030 (2017) [ Accessed 2020Jul23]; Available from: https://www.cepal.org/es/temas/proyecciones-demograficas/estimaciones-proyecciones-poblacion-total-urbana-rural-economicamente-activa.

- Benavides JA, Ovalle OO, Salvador GR, et al. 2012. Population-based surveillance for invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia in infants and young children in Bogota, Colombia. Vaccine. 30(40):5886–5892.

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE). Historic Annual IPC, DANE, Colombia (2019) [ Accessed 2020Jul23]; Available from: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/precios-y-costos/indice-de-precios-al-consumidor-ipc/ipc-historico#variaciones-ipc-base–2008.

- XE Currency Data. Historic exchange rate between US dollar and the Colombian peso (2019) [ Accessed 23 July 2020]; Available from: https://www.xe.com/es/currencytables/.

- Castaneda-Orjuela C, Romero M, Arce P, et al. 2013. Using standardized tools to improve immunization costing data for program planning: the cost of the Colombian Expanded Program on Immunization. Vaccine. 31(Suppl 3):C72–9.

- Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO). PAHO, Expanded Program of Immunization, Vaccine Prices between 2011–2019 (2019) [ Accessed 2019Apr1]; Available from: https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1864:paho-revolving-fund&Itemid=4135&lang=en.

- Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), World Health Organization. Health in the Americas. Colombia (2017) [ Accessed 2020Jul23]; Available from: https://www.paho.org/salud-en-las-americas-2017/?p=2342.

- Ministry of Health. Lineamientos para la gestión y administración del Programa Ampliado de Inmunizaciones (PAI) (2019) [ Accessed 2020Jul23]; Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/PP/ET/lineamientos-gestion-administracion-pai.pdf.

- Ministry of Health. The Ministry of Health starts an initiative for Malaria elimination in Colombia. News bulletin No. 185 (2019) [ Accessed 23 July 2020]; Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/Minsalud-lanza-Iniciativa-de-Eliminacion-de-la-Malaria-en-Colombia.aspx.

- Ministry of Health. Combined prevention, an effective response in the fight against HIV/ AIDS. News bulletin No. 180 (2019) [ Accessed 2020Jul23]; Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/Prevencion-combinada-respuesta-efectiva-en-lucha-contra-VIHSida.aspx.

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. Colombia (2019) [ Accessed 2019Dec1]; Available from: https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS&country=COL.

- Ministry of Health. $31.8 billons for health in 2020. News bulletin No. 1 (2020) [ Accessed 2020Jul23]; Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/31-8-billones-para-la-salud-en-2020.aspx.

- World Health Organization. Immunization Financing Indicators. Colombia (2020) [ Accessed 2020Jan1]; Available from: https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/financing/data_indicators/en/.

- O’Riordan M, Fitzpatrick F. The impact of economic recession on infection prevention and control. J Hosp Infect. 2015;89(4):340–345.

- Maltezou HC, Lionis C. The financial crisis and the expected effects on vaccinations in Europe: a literature review. Infect Dis (Lond). 2015;47(7):437–446.

- Gellin B, Landry S. The value of vaccines: our nation’s front line against infectious diseases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88(5):580–581.

- Quilici S, Smith R, Signorelli C. Role of vaccination in economic growth. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2015;3:1. 27044. DOI:10.3402/ jmahp.v3.27044

- Borgonovi E, Compagni A. Sustaining universal health coverage: the interaction of social, political, and economic sustainability. Value Health. 2013;16(1 Suppl):S34–8.