ABSTRACT

Background: Transthyretin amyloid polyneuropathy (ATTR-PN) is a fatal disease associated with substantial burden of illness. Three therapies are approved by the European Medicines Agency for the management of this rare disease. The aim of this study was to compare the total annual treatment specific cost per-patient associated with ATTR-PN in Spain.

Methods: An Excel-based patient burden and cost estimator tool was developed to itemize direct and indirect costs related to treatment with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis in the context of ATTR-PN. The product labels and feedback from five Spanish ATTR-PN experts were used to inform resource use and cost inputs.

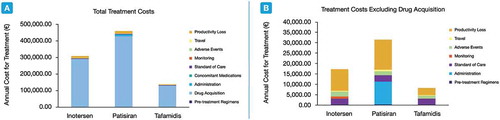

Results: Marked differences in costs were observed between the three therapies. The need for patisiran- and inotersen-treated patients to visit hospitals for pre-treatment, administration, and monitoring was associated with increased patient burden and costs compared to those treated with tafamidis. Drug acquisition costs per-patient per-year were 291,076€ (inotersen), 427,250€ (patisiran) and 129,737€ (tafamidis) and accounted for the majority of total costs. Overall, the total annual per-patient costs were lowest for patients treated with tafamidis (137,954€), followed by inotersen (308,358€), and patisiran (458,771€).

Conclusions: Treating patients with tafamidis leads to substantially lower costs and patient burden than with inotersen or patisiran.

1. Introduction

Transthyretin (TTR) amyloid polyneuropathy (ATTR-PN) is a rare and progressive multisystemic disease caused by mutations in the TTR gene, resulting in the deposition of misfolded protein aggregates in peripheral nerves [Citation1,Citation2]. TTR fibril deposition in other organs and tissues, such as the heart, kidney and ocular vitreous, are also frequent manifestations that contribute to the morbidity and poor prognosis among patients with this disease. Over 120 variants of the TTR gene have been identified to date, and the majority are pathogenic with varying levels of penetrance [Citation1,Citation3]. Untreated ATTR-PN can be fatal within 6–12 years of disease onset but can vary depending on genotype, endemic region, and clinical presentation [Citation1,Citation4–7].

Three disease-modifying pharmacotherapies for the management of ATTR-PN are now available for patients who previously had only liver transplantation or supportive care as therapeutic options. Tafamidis (Vyndaqel®; Pfizer Inc., Belgium) is an oral small molecule TTR stabilizer that was first approved in Europe by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2011 [Citation8]. As of 2018, two gene silencing biologic therapies, inotersen (Tegsedi®; Akcea Therapeutics, Ireland) and patisiran (Onpattro®; Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Netherlands), have also received marketing authorization in Europe [Citation9,Citation10]. Randomized controlled phase III trials have demonstrated that inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis are efficacious in patients with ATTR-PN [Citation11–13].

Although ATTR-PN is rare worldwide, there are descriptions of several endemic foci in Spain, such as in Majorca, Balearic Islands, Valverde del Camino (Huelva), the Safor area (Valencia), Barcelona, Cantabria, and Vigo (Galicia) [Citation14]. The prevalence rates in these high endemic regions range from 1 per 100,000 inhabitants in Minorca and 5 per 100,000 inhabitants in Majorca [Citation14]. In Spain, tafamidis has been available and reimbursed for ATTR-PN treatment since December 2013, and inotersen and patisiran were recently accepted for reimbursement. Given the known substantial patient and economic burden of ATTR-PN [Citation15] and the options that are now available to patients and prescribing physicians, it has become increasingly important to understand the difference in patient burden and overall cost among the pharmacotherapeutic therapies available. Besides drug cost, consideration should be given to the broader impact on healthcare resources and burden to patients and their caregivers during the treatment selection process. A comparison of the total economic burden (in terms of cost and hours lost) associated with treating ATTR-PN with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis has not yet been conducted. The objective of this study, therefore, is to compare the total direct and indirect costs related to receiving treatment with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis in Spain.

2. Methods

2.1. Analysis framework and clinical expert survey

A patient burden and cost estimator tool was developed in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to quantify and compare the expected total time and cost burden of treatment for a hypothetical patient with ATTR-PN who is treated with either inotersen, patisiran, or tafamidis over a one-year period. The patient burden and cost estimator tool considered costs to the healthcare system, patient, and societal perspectives to comprehensively capture the treatment-related economic burden beyond drug costs. In addition to drug acquisition costs, other costs that are directly or indirectly associated with exposure to inotersen, patisiran, or tafamidis were included, such as administration, pre-treatment and concomitant medication requirements, adverse events (AEs) and monitoring, background disease management, travel, and patient and caregiver productivity loss. These inputs, as well as the resource use and cost data used to inform them, were identified for inclusion in the analysis based on publicly available literature and a data collection survey, which used a questionnaire to derive estimated values of healthcare usage/burden to serve as inputs to the patient burden and cost estimator tool. This survey was conducted among a panel of five clinical experts. The panel of nationally and internationally recognized Spanish experts included internists (N = 2), neurologists (N = 1), and pharmacists (N = 2) with extensive experience in treating ATTR-PN patients with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis. Responses from the survey were primarily used to confirm that Spanish treatment approaches align with the data extracted from product labels. Given limited data availability in the published literature from Spain to fully populate the cost estimator tool, the survey was also used to collect real-world patient characteristics, cost estimates, resource use data, and patient burden associated with travel and productivity loss. Cost inputs are collected and reported as Euro (€) in 2020 values. Where necessary, medical costs were inflated using the healthcare component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Spain, while all other costs were directly inflated using the Spanish CPI [Citation16].

2.2. Drug and administration costs

Disease-modifying drugs for ATTR-PN (inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis) and medications related to pre-treatment regimens and concomitant treatment contributed to overall drug costs in the patient burden and cost estimator tool. Drug acquisition costs for inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis were based on their approved posology and current public ex-factory prices including the corresponding mandatory deduction outlined in Royal Decree 08/2010 of 4% ( [Citation17–21];).

Table 1. Posology and drug costs for therapies approved for ATTR-PN treatment

Inotersen is provided to patients in a pre-filled syringe for subcutaneous self-injection. Concomitant vitamin A supplementation is recommended because inotersen treatment has been linked to vitamin A deficiency [Citation19]. Responses from the survey indicate that, in Spanish real-world clinical practice, patients treated with inotersen are prescribed a vitamin A supplement of 50,000 international units (IU) every 15 days. The vitamin A costs were identified using a Spanish drug cost database [Citation21].

Patisiran is provided to patients by intravenous (IV) administration in the hospital by a medical professional, with a weight-dependent dose of 0.3 mg/kg every 3 weeks. Based on clinical opinion from the survey, the mean weight of a Spanish patient with ATTR-PN is 70.87 kg. Given that patisiran is provided in 10 mg vials, it would require 3 vials to treat a 70.87 kg patient with a dose of 21.26 mg. Additionally, as required by the product label, patients treated with patisiran incur costs associated with receiving a prophylactic pre-treatment regimen to minimize the risk of infusion-related reactions with every IV administration [Citation18]. In accordance with the product label and real-world clinical practice, the pre-treatment medications included IV dexamethasone (10 mg), IV diphenhydramine (50 mg), IV ranitidine (50 mg), and oral paracetamol (500 mg; [Citation18]). The hospital chair time unit cost (100.00€ per hour), provided from expert feedback, and the material and service costs for the infusion procedure (207.93€) were factored into the cost per patisiran administration [Citation22,Citation23]. From the survey, it was determined that a total of 260 minutes is required to receive patisiran treatment. This time includes 60 minutes for the preparation and administration of the pre-treatment regimen, a 60-minute waiting period following the pre-treatment regimen, 80 minutes for the preparation and administration of patisiran, and an additional 60-minute monitoring period following administration [Citation18]. Similar to inotersen, vitamin A supplementation is also recommended in patients treated with patisiran [Citation18].

In contrast to inotersen and patisiran, tafamidis is provided as a capsule to be taken orally by the patient at home and does not incur fees for administration. Furthermore, concomitant vitamin A supplements are not required with tafamidis.

In the patient burden and cost estimator tool, the cost per dose of each drug was multiplied by the dosing frequency per year and summed to derive the annual costs of drug acquisition, pre-treatment, and concomitant medications. The assumption of 100% patient compliance and drug wastage was applied to all regimens in this analysis.

2.3. AEs and monitoring costs

Given that safety data from the three pivotal clinical trials showed that inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis were generally well-tolerated, treatment-related AEs were considered to be mild to moderate in severity (grades 1 and 2) in this analysis [Citation11–13]. The AEs were selected for inclusion if they were reported as being very common (occurred with frequency of ≥1 in 10 patients) or of special interest in the product labels and clinical trials. The AE rates from the pivotal phase III clinical trials were converted to annual probabilities. The annual AE management costs were calculated based on the probabilities of occurrence and the event cost of each AE from the Database of Spanish Healthcare Costs (; [Citation22]).

Table 2. Management costs of AEs related to treatment with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis

Notably, patients exposed to inotersen received enhanced monitoring during the clinical trial, given the higher occurrence of thrombocytopenia and kidney failure in the inotersen group [Citation13]. As such, the product label states that patients receiving treatment with inotersen should undergo monitoring to prevent undesired complications [Citation19]. According to the product label and in agreement with the clinical expert survey, patients treated with inotersen undergo biweekly platelet count tests (29.18€ per test), as well as quarterly estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) tests (21.76€ per test), urine protein creatinine ratio tests (0.77€ per test), and hepatic enzyme tests (36.38€ per test; [Citation22]). The annual cost of monitoring for a patient treated with inotersen was calculated as the sum product of the annual monitoring frequency and the cost of each test from the Database of Spanish Healthcare Costs [Citation22].

2.4. Standard of care costs

In addition to using disease-modifying agents to slow neuropathy progression, patients with ATTR-PN require treatments for symptom management purposes. The direct medical cost associated with standard of care (SOC) in this analysis was 3,109.05€, which was inflated from the annual mean per-patient cost estimate (minus the drug costs to mitigate the risk of double counting) derived from a previously published cost of illness and burden of disease study in patients with ATTR-PN in Portugal [Citation24]. A similar SOC cost was obtained from the panel of clinical experts. As the SOC cost was equally applied across all three comparators in the patient burden and cost estimator tool, it bears no impact on incremental cost differences between treatments. Values from the Portuguese study were included in our cost estimator tool due to the availability of peer-reviewed data for a robust cost of illness analysis, the use of a similar currency (€), and because Portugal and Spain share common healthcare characteristics and both exhibit endemic foci of ATTR-PN with the same common mutation (Val30Met) [Citation25].

2.5. Travel and productivity loss costs

No data were identified in the literature to inform the patient burden and cost estimator tool about indirect costs associated with receiving inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis treatment for ATTR-PN. As such, responses from the clinical expert survey were used to inform remaining data gaps in the cost estimator tool related to travel, work absenteeism, and foregone leisure time for patients and their caregivers.

According to the clinical experts, the mean travel frequency for patients receiving inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis was 14.75, 21.40 and 8.2 times per year, respectively, for treatment, monitoring tests, and follow-up. Additionally, it was determined that the mean distance traveled from home to the hospital/pharmacy was 46.06 km and was assumed to be the same for all three therapies. The total cost associated with travel also considered that hospital parking among patients treated with inotersen and tafamidis would not exceed the one-hour rate, while those treated with patisiran may require at least 4.33 hours of parking to accommodate the duration of administration. The cost per unit distance traveled was 0.58€/km and the parking fee was 2.35€/hour [Citation22,Citation26]. To calculate travel costs, the annual travel frequency was multiplied by the mean distance traveled and the cost per unit distance. The product of the hourly parking fee and the annual travel frequency was subsequently added to the travel cost in order to determine the total costs.

Loss of productivity at work and leisure time among patients and caregivers related to treatment with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis were based on clinician responses from the survey as well (). The estimated mean productivity hours lost per week were multiplied by the calculated mean hourly labor cost per worker for all occupations in Spain (inflated to 17.06€ [Citation27]). The estimated mean leisure hours lost per week were multiplied by the assumed hourly value of leisure time in Spain (inflated to 5.37€ [Citation28]). Although there is no established value of leisure time in Spain, the estimate used in this analysis is aligned with the methodology described in a previous publication [Citation28]. The resulting costs for productivity and leisure time lost were summed to calculate the total annual indirect costs.

Table 3. Estimated mean weekly productivity and leisure time loss among patients treated with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis

3. Results

In this assessment, the total treatment burden and costs associated with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis were aggregated across seven direct cost categories and two indirect costs categories.

The total healthcare costs were generally highest for patients receiving patisiran, which incurred unique costs in two categories (). In contrast, costs were lowest across all categories for patients receiving tafamidis. For all three therapies, drug acquisition accounted for the majority of the total costs and strongly contributed to the overall medical cost differences between therapies. Other cost differences between treatments were due to the administration requirements of patisiran (11,147.60€) and the monitoring requirements associated with inotersen (996.93€). The annual costs of AE management were also notable across all three treatment but was greatest with inotersen treatment, followed by patisiran and then tafamidis.

Table 4. Total healthcare costs due to treatment with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis

The indirect costs determined in this study included travel and productivity loss costs. Some degree of travel was required by all patients, regardless of their ATTR-PN therapy, for various treatment-related reasons, such as pharmacy pickup, administration, monitoring, and follow-up. Absent from the need for in-hospital administrations and frequent monitoring, tafamidis yielded the shortest annual distance traveled of 377.69 km, with an annual cost of 238.33€. In contrast, patients treated with inotersen and patisiran were required to travel 679.39 km and 985.68 km, resulting in annual costs of 428.71€ and 823.15€, respectively.

Finally, receiving treatment is associated with a reduction in time available for work and leisure for patients and their caregivers. The total weekly work and leisure time loss due to treatment for patients and caregivers combined were estimated to be 804, 1,416 and 267 minutes per week with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis, respectively. Therefore, approximately 699, 1,231 and 232 annualized hours were lost among patients and caregivers for treatment with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis, respectively. Accounting for the monetary value of work and leisure time reveals that treatment with tafamidis was associated with a lower annual cost (3,442.77€) than with inotersen or patisiran (10,403.31€ and 14,420.28€, respectively).

Taken together, the total annual per-patient cost burden for treatment with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis in this analysis were 308,358€, 458,771€ and 137,954€, respectively (). Thus, treating patients with patisiran was 49% more costly compared to treating a patient with inotersen. Similarly, patisiran was 233% more costly compared to tafamidis, while treatment with inotersen was 124% more costly than with tafamidis. Drug acquisition costs were the main contributor to the total annual costs across all three comparator therapies. A scenario analysis exploring total costs in the absence of drug acquisition costs, nonetheless, yielded similar conclusions as the base case analysis ().

Figure 1. Total annual costs among patients treated with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis in the base case analysis

As patisiran was associated with the highest total annual costs in this analysis, an alternative assumption allowing for home administration was tested in a scenario analysis. Home administration slightly lowered the total treatment cost for patisiran by 8,237.70€ (−1.8%) compared to the base case results.

4. Discussion

This is the first analysis to examine treatment-related patient burden and costs beyond drug acquisition, administration, and AEs among patients with ATTR-PN. Patient burden and costs related to pre-treatment, concomitant medications, monitoring, travel, and productivity loss were also accounted for in this analysis. Publicly available data and a clinician survey were used to inform a patient burden and cost estimator tool for conducting a comparative treatment burden and cost analysis associated with treating patients with ATTR-PN in Spain. We show that there are large cost variations between the three therapy options, ranging from 137,954€ (for tafamidis) to 458,771€ (for patisiran), mainly due to drug acquisition. Conclusions from the base case analysis also remained unchanged in all scenario analyses testing alternative cost assumptions.

It is becoming increasingly clear that ATTR-PN imposes substantial time loss and health-related burden on patients and caregivers. In a study conducted by Stewart et al., ATTR-PN was associated with substantial impairments in physical health, quality of life, and work productivity among patients in Spain and in the US, as well as poor mental health and work impairment among caregivers [Citation15]. Results from our survey, in which time loss was strictly treatment-related, indicated that the combined work productivity time loss among patients and caregivers was greatest for patisiran (12.8 h/week) and lowest for tafamidis (3.6 h/week). While we assumed that the hypothetical patient in our cost estimator tool is employed full-time to enable fair comparisons between therapies, results from our survey of clinical experts revealed that employment status varies substantially between therapies. The mean full-time employment rates of 4%, 22%, and 53% were estimated for patients treated with inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis. An interpretation of this finding could suggest that employable, and presumably younger, patients are more likely to be prescribed tafamidis earlier in their disease in order to mitigate the heightened time loss associated with other ATTR-PN treatments.

Although travel is often overlooked, it represents another significant burden in patients with diseases like ATTR-PN that affect mobility. Patients must often travel to centers of excellence to find providers with expertise in this rare condition. One meta-analysis, which included 108 studies across a wide range of care settings and diseases, reported that farther travel to healthcare services was associated with reduced patient outcomes and attendance at follow-up [Citation29]. Results from the APOLLO study further highlight the impact of this consideration, especially in patients with advanced disease. Among patients with stage 2 disease, it was reported that 50% of patients were not able to travel by public transportation and 89% of patients required mobility assistance devices [Citation12,Citation30]. Although receiving treatment with patisiran at home is an option for select patients [Citation18], our base case analysis assumed all patisiran treatment took place in the hospitals. In support of this, clinical experts responded that more than half of patients (55.7%) receive treatment in hospitals. The COVID-19 pandemic, which was taking place while the survey was conducted, may have contributed to a sudden increase in patients receiving patisiran treatment at home. Nonetheless, the impact of home treatment for patisiran was limited, as the total costs were only reduced by 1.8% in this scenario analysis.

A strength of the analysis is that the patient burden and cost estimator tool was designed to reflect how patients are treated in real-life according to established treatment guidelines and real-world practices, based on the clinicians’ experiences with treating patients with ATTR-PN in Spain. For this reason, drug wastage was included in the analysis and directly impacted drug costs. Unlike oral administration of tafamidis as one capsule per day and subcutaneous administration of inotersen as one pre-filled syringe per week, patisiran IV administration can require two or three vials per dose depending on patient weight. Since the product label states that patisiran is for single-use only and unused portions of the medicine should be discarded [Citation18], variations in patient weight can be associated with substantial drug wastage costs.

The number of clinical experts that completed the survey for this study was restricted by the rarity of ATTR-PN. Despite this potential limitation, replies to the survey questions were generally consistent across all respondents from endemic and non-endemic regions in Spain, suggesting that treatment practices for ATTR-PN management are likely going to be generalizable across ATTR-PN treatment sites in Spain. Moreover, responses from the clinical experts were also consistent with the publicly available and peer-reviewed data that were used to inform the cost estimator tool, thereby making it possible to extrapolate these analyses to regions outside Spain.

In addition to costs, patients and decision makers rely on efficacy and safety data for the selection of treatment regimens. Although randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis are efficacious and safe for patients with ATTR-PN [Citation11–13], the comparative efficacy of these drugs is unknown. A recent study conducted by Samjoo et al. concluded that an indirect comparison of inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis for the treatment of ATTR-PN, using the currently available randomized controlled trials, is not feasible given notable clinical heterogeneity in the enrolled patient populations and differences in outcome definitions for measuring neuropathy impairment that could bias the interpretation of the results [Citation31]. Accordingly, our study examined the annual economic burden for a hypothetical patient on these treatments without reference to efficacy.

While previous studies have characterized the considerable burden of illness and societal costs associated with ATTR-PN and standard of care management [Citation15,Citation24], cost of treatment by ATTR-PN therapy was not evaluated in these studies. Therefore, our study aimed to quantify and compare the unique differences in treatment-related costs and patient burden between inotersen, patisiran, and tafamidis to better understand their impact on patients and on the health care system. Consistent with Ines et al. [Citation24], though, our cost estimator tool also demonstrates that the financial burden for treatment of ATTR-PN are driven by drug costs. The patient burden and cost estimator tool developed in this study revealed that treatment with tafamidis incurred the lowest annual cost, followed by inotersen and then patisiran. Although direct costs were the primary drivers in the analysis, this study also revealed significant differences in indirect costs between treatments. The administration requirements of patisiran and monitoring requirements of inotersen largely contributed to the increased productivity and leisure time loss compared to tafamidis. In patients with limited mobility, and particularly during times of national and international travel restrictions, the prospect of remote care represents an important consideration for patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers alike.

5. Conclusions

This is the first analysis to consider direct and indirect costs for treating ATTR-PN beyond drug acquisition. Treating patients with tafamidis would result in substantially lower costs and lower patient burden compared to treating patients with inotersen or patisiran.

Author contributions

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article. All authors had full access to the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. CP, DT, PL, MS, PM, PT and MHR designed the study and developed the clinical survey. LG, JG-M, JMM-S, FM-B, and MDS-R provided expert responses. DT and PL developed the patient burden and cost estimator tool, interpreted the data, conducted the analyses, and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. LG has disclosed that they received speaker and advisory honoraria from Pfizer, Alnylam, Akcea and Grunenthal. JG-M has disclosed that they received speaker and advisory honoraria from Pfizer, Alnylam and Akcea. JMM-S, FM-B, and MDS-R have disclosed that they received speaker and advisory honoraria from Pfizer (Spain). CP, MS, PM, PT and MHR have disclosed that they are full-time employees of Pfizer and hold stock and/or stock options. DT and PL have disclosed that they are employees of EVERSANA who were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with the design of the study, development of the clinical survey and patient burden and cost estimator tool, interpretation of the data, conducting the analyses and drafting the manuscript.

References

- Luigetti M, Romano A, Di Paolantonio A, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR) polyneuropathy: current perspectives on improving patient care. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2020;16:109–123.

- Ando Y, Coelho T, Berk JL, et al. Guideline of transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis for clinicians. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013 Feb 20;8:31

- Ohmori H, Ando Y, Makita Y, et al. Common origin of the Val30Met mutation responsible for the amyloidogenic transthyretin type of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. J Med Genet. 2004 Apr;41(4):e51

- Adams D, Suhr OB, Hund E, et al. First European consensus for diagnosis, management, and treatment of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016 Feb;29(Suppl 1):S14–26

- Coelho T, Ines M, Conceicao I, et al. Natural history and survival in stage 1 Val30Met transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Neurology. 2018 Nov 20;91(21):e1999–e2009.

- Adams D, Ando Y, Beirao JM, et al. Expert consensus recommendations to improve diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis with polyneuropathy. J Neurol. 2020 Jan 6.

- Gonzalez-Duarte A, Conceicao I, Amass L, et al. Impact of Non-cardiac clinicopathologic characteristics on survival in transthyretin amyloid polyneuropathy. Neurol Ther. 2020 Jun;9(1):135–149

- European Medicines Agency: Vyndaqel. Vyndaqel [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/vyndaqel

- European Medicines Agency: Tegsedi. Tegsedi [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/tegsedi

- European Medicines Agency: Onpattro. Onpattro [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/onpattro

- Coelho T, Maia LF, Martins Da Silva A, et al. Tafamidis for transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2012 Aug 21;79(8):785–792.

- Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O’Riordan WD, et al. Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 5;379(1):11–21.

- Benson M, Waddington-Cruz M, Berk JL, et al. Inotersen Treatment for Patients with Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 5;379(1):22–31.

- Buades Reines J, Vera TR, Martin MU, et al. Epidemiology of transthyretin-associated familial amyloid polyneuropathy in the Majorcan area: son Llatzer Hospital descriptive study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014 Feb 26;9:29

- Stewart M, Shaffer S, Murphy B, et al. Characterizing the high disease burden of transthyretin amyloidosis for patients and caregivers. Neurol Ther. 2018 Dec;7(2):349–364

- European Central Bank. HICP - Indices, breakdown by purpose of consumption. Sept 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 09] . Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/ecb_statistics/escb/html/table.en.html?id=JDF_ICP_COICOP_INX

- Summary of Product Characteristics [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/vyndaqel-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Summary of Product Characteristics [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/onpattro-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Summary of Product Characteristics [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/tegsedi-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Real-Decreto-Ley-8/2010,m.2010. Available from: http://www.boes.es

- BotPlus. Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 06]. Available at: https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/

- [Base de datos de costes sanitarios eSalud]. Barcelona: oblikue consulting, [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Feb 13]. Available at:

- Scientificfilters.com. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 08]. Available at: scientificfilters.com/membrane-filters/pes

- Ines M, Coelho T, Conceicao I, et al. Societal costs and burden of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis polyneuropathy. Amyloid. 2020 Jun;27(2):89–96

- Munar-Ques M, Saraiva MJ, Viader-Farre C, et al. Genetic epidemiology of familial amyloid polyneuropathy in the Balearic Islands (Spain). Amyloid. 2005 Mar;12(1):54–61

- Ayuntamiento DM [cited 2020 Feb 17]. Available at: https://www.madrid.es/UnidadesDescentralizadas/UDCMovilidadTransportes/SER/Descriptivos/ficheros/Tarifas%20SER%20desde%2001_06_2017.pdf

- Instituto national de estadistica. [cited 2020 Feb 17]. Available at: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736060920&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735976596

- Oliva-Moreno J, Pena-Longobardo LM, Garcia-Mochon L, et al. The economic value of time of informal care and its determinants (The CUIDARSE Study). PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0217016

- Kelly C, Hulme C, Farragher T, et al. Are differences in travel time or distance to healthcare for adults in global north countries associated with an impact on health outcomes? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016 Nov 24;6(11):e013059.

- National Institute for Health Excellence. Highly specialised technology evaluation: patisiran for treating hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. 2018.

- Samjoo IA, Salvo EM, Tran D, et al. The impact of clinical heterogeneity on conducting network meta-analyses in transthyretin amyloidosis with polyneuropathy. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020 May;36(5):799–808