ABSTRACT

Background

As healthcare management of highly active-relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (HA-RRMS) patients is more complex than for the whole multiple sclerosis (MS) population, this study assessed the related economic burden from a National Health Insurance’s (NHI’s) perspective.

Research design and methods

Study based on French NHI databases, using individual data on billing and reimbursement of outpatient and hospital healthcare consumption, paid sick leave and disability pension, over 2010–2017.

Results

Of the 9,596 HA-RRMS adult patients, data from 7,960 patients were analyzed with at least 2 years of follow-up. Mean annual cost/patient was €29,813. Drugs represented 40% of the cost, hospital care 33%, disability pensions 9%, and all healthcare professionals’ visits combined 8%. Among 3,024 patients under 60 years-old with disability pension, disability pension cost €7,168/patient/year. Among 3,807 patients with paid sick leave, sick leave cost €1,956/patient/year. Mean costs were €2,246/patient higher the first year and increased by €1,444 between 2010 and 2015, with a €5,188 increase in drug-related expenditures and a €634 increase in healthcare professionals’ visits expenditures but a €4,529 decrease in hospital care expenditures.

Conclusions

The cost of health care sick leaves, and disability pensions of HA-RRMS patients was about twice as high as previously reported cost of MS patients.

1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system. It disables the patient and impacts her/his quality of life, and with time, causes a significant and irreversible disability with a progressive loss of autonomy, eventually confining the patient to a wheelchair. Over 2010–2015, about 110,000 persons had MS in France [Citation1], corresponding to a national prevalence of approximately 150 patients per 100,000 inhabitants [Citation2].

MS is classified into relapsing or progressive forms, with Relapsing-Remitting MS (RRMS) accounting for 85% to 90% of all initial diagnoses [Citation3]. There is yet a group of patients which remains difficult to define and for which there is no consensus about their treatment [Citation4–6]. These patients have frequent relapses and/or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) activity (either when untreated or while on a Disease-Modifying Therapy [DMT]) and have what might be termed as a Highly Active RRMS (HA-RRMS) [Citation5,Citation7].

Although no cure for MS yet exists, current treatments aim to mitigate the symptoms, reducing the frequency and severity of relapses, while preventing disability progression. MS therapeutic management involves an array of healthcare professionals, hospital admissions, long-term treatments, outpatient visits, supportive care, laboratory tests, imaging procedures, and medical devices (*see examples). Due to the young age of onset, progressively incapacitating nature and life-long duration of the disease, the economic burden of MS for patients, their families, and society is high [Citation8].

Studies on the burden of illness conducted in France and Canada have demonstrated that relapses are associated with increased healthcare resource utilization and increased direct and indirect costs of €2,305 (in patients with an Expanded Disability Scale [EDSS] score ≤6) and CAN$ 10,512 (with EDSS score ≤5) per relapse, respectively [Citation9,Citation10]. Furthermore, in a US study, the healthcare costs (excluding DMTs) of patients with two or more relapses per year was almost twice as high as the cost of MS patients with one or no relapse [Citation11].

Previous studies on the healthcare expenditure among MS patients have been carried out in France. In 2013, a study on the French National Health Insurance (NHI) database SNDS (Système National des Données de Santé) reported a mean healthcare expenditure of €11,900 per patient, with drugs and hospitalization accounting for 47% and 23% of the total cost, respectively [Citation12]. In 2015, a study based on a patient survey estimated that direct healthcare cost among MS patients to be €21,800 per patient (including patient co-payments, out-of-pocket costs, services, and informal care costs, without sick leave and disability pension) [Citation10].

However, none of these studies examined costs among HA-RRMS patients, whose healthcare management is more complex and related costs could be higher as already reported for patients with progressive MS and severe disability [Citation13]. In addition, these studies were conducted over a short follow-up period (1 year). Therefore, this study was designed to better characterize HA-RRMS patients in France, their management, and their corresponding economic burden. The focus is on incident HA-RRMS patients to examine HA-RRMS patients at the time of what can be considered as their diagnosis and the following years.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and data sources

We performed a longitudinal retrospective cohort study on the French National Health Insurance (NHI) databases (SNDS) and specifically, on data extracted from the SNIIRAM (Système National d’Information Inter-Régimes de l’Assurance Maladie) database [Citation14]. The NHI covers all people living in France, irrespective of wealth, age, or work status. The NHI has several schemes (there are no major differences between these schemes in terms of coverage) and we included patients covered by the General Scheme (excluding the local mutualist sections, Sections Locales Mutualistes), representing 76% of the national population [Citation14]. The NHI database gathers anonymized individual data used for billing and reimbursement of inpatient and outpatient healthcare consumption [Citation15].

Several DMTs have been approved for the treatment of MS over the last 20 years [Citation16]. At the time of study initiation, two immunosuppressants – called high efficacy DMT (HE DMT) – were recommended for patients with active disease and an insufficient response to at least one drug, as well as for patients with rapidly evolving severe RRMS. More HE DMT later became available. The inclusion date (index date) was defined as the date of the first reimbursement of HE DMTs or the date of relapse during the study period. Patients were included from 01/01/2010 to 31/12/2015 and followed until death, one year without any care expenditure or the end of the study (31/12/2017), whichever occurred first. The study periods enabled to follow patients for at least 2 years to capture meaningful information related to HA-RRMS management over time, especially the evolution of available treatments.

Most of healthcare expenditures for long-term diseases’ management (LTD), such as MS, are 100% reimbursed by the NHI [Citation17]. Most of the remaining medical fees (out-of-pocket expenses) [Citation18] are covered by an optional private health insurance or eligible for state funded free complementary health care [CMUc (Couverture Médicale Universelle complémentaire)] (provided that annual income is below 50% of the poverty threshold) [Citation19].

2.2. Study population

The study population comprised all incident HA-RRMS adults (≥18 years old) identified during the inclusion period and continuously affiliated to the General health insurance Scheme between two years prior to the index date and 2017. As there is no code for HA-RRMS in the database, an algorithm was developed with two neurologists to identify HA-RRMS patients. Patients were included if they met at least one of the following criteria:

1) Treatment criterion: At least one reimbursement of HE DMT (natalizumab, fingolimod);

2) Relapse criterion: At least two relapses in one year and no previous treatment for MS during the previous two years and an MRI of the central nervous system performed during the three months following the second relapse and a DMT during the six months following the MRI;

3) Relapse criterion: One relapse in one year despite a DMT, with an MRI of the central nervous system performed during the three months following the relapse and a switch of DMT during the six months following the MRI.

Of note, mitoxantrone has been used to treat aggressive RRMS patients. However, it is included in the price of the hospital stay and not recorded at the patient-level. Therefore, this drug could not be used in our study to identify HA-RRMS patients.

Relapses were defined using a validated US claims-based algorithm [Citation11], and adapted to French clinical practice, with combined 1) a hospitalization with a principal diagnosis (PD) of MS (PD with International Classification of Disease 10th revision [ICD-10]: G35 ‘Multiple sclerosis’) excluding hospitalization for administration of MS treatment (PD with ICD-10: Z51.2 and related diagnosis (RD)/significant associated diagnosis [SAD] ICD-10: G35), for a surgery disease-related group (GHM [Groupe Homogène de Malades]) or a GHM with botulinum toxin injection; 2) and/or a hospital or outpatient neurologist visit in addition to an oral or intravenous corticoid reimbursement (methylprednisolone/≥ 1 g) within 15 days of the visit. Relapse events that occurred within the same 30-day period were treated as a single relapse.

We excluded patients without unique identification number. We also excluded patients treated with natalizumab and at least one hospitalization for administration of therapy for Crohn’s disease the year prior to the index date; patients treated by natalizumab with a missing hospital diagnosis at index date and without hospitalization for MS (PD/RD/SAD) the year following to the index date. Incident HA-RRMS patients were defined as patients without reimbursement for HE DMTs and/or without MS relapse(s) (as defined above) 12 months prior to the index date. HE DMT discontinuation was defined as three months without natalizumab infusion or three months after end of last tablets dispensed for fingolimod. Switch of DMT was defined as dispensing of the alternative DMT six months following the date of discontinuation of the initial DMT.

2.3. Economic endpoints

Healthcare resources use and their related costs were identified using the French NHI (payer) perspective. Outpatient healthcare costs were estimated using reimbursements made by the NHI to the beneficiary; Hospital healthcare costs were estimated based on economic data provided by the ATIH (Technical Agency for Hospitalization Information) and integrated into SNDS. The cost of a hospital care includes the price of the drug (and its dispensing), inpatient healthcare professional visits, the medical exams and imaging procedures performed, and the facility costs. The hospitalization can take place in a hospital or at home (home care). Retrieved costs of HA-RRMS patients management included not only HA-RRMS-related costs but also costs related to the management of other diseases and injuries, as the distinction was not possible. Costs are in EUR of the corresponding year. At each calendar year, the healthcare costs are those of the incident patient of the current year and the incident patients of the previous years.

Paid sick leave is granted to employees and unemployed individuals who have worked a minimum number of hours. It is not paid (regulatory waiting period) during the first 3 days on the first sick leave period over a 3-year period, for patients with LTD. The sick leave allowance represents 50% of the salary, with a maximum of €1,385 (gross, in 2020) [Citation20]. Based on medical decision, disability pensions can be granted to employees <62 years old. There are three levels of pension, based on the severity of the disability. Level 1 is for disabled employees able to perform a paid job, level 2 is for disabled employees unable to perform a paid job, and level 3 is for disabled employees unable to perform a paid job and in addition, requiring assistance from a third party to perform everyday tasks [Citation21].

3. Statistical analyses

Only descriptive analyses were performed. Continuous, quantitative variables were summarized with the number of patients, mean, and standard deviation (SD). Categorical, qualitative variables were summarized with the percentage of patients per category.

4. Results

4.1. Patient demographics and healthcare resources used

Over 2010–2015, we identified 12,830 HA-RRMS prevalent adults. Among them, 9,596 were incident patients (6,704 patients selected with criterion 1 [69.9%], 173 patients with criterion 2 [1.8%], and 2,719 patients with criterion 3 [28.3%]). Incident patients were followed-up for a mean duration of 4.0 years and up to eight years, corresponding to 38,394 patients-years.

The majority of incident patients was female (73.7%) and the mean age was 39.9 years old (SD 10.5) (). Most of the patients (99.4%) had an LTD status. Of the 9,238 patients under 60 years old, 19.1% had a disability pension. Most of these patients had a level-2 disability pension and 78.5% maintained the same disability pension level (or absence of pension) during the study.

Table 1. Highly active relapsing-remitting adult incident patients’ characteristics (N = 9,596)

summarizes the main healthcare resources (MS-related and not MS-related) used during the study by the 8,045 patients with at least 2 years of follow-up (83.8% of incident patients). Around 40% and 84% of patients took at least one DMT and one HE DMT, respectively. In detail, 61.1% and 38.2% of patients were treated with fingolimod and natalizumab at least once, respectively. The mean duration of the HE DMT treatment before discontinuation was 3.5 years.

Table 2. Healthcare use (all disease and injuries combined) of highly active relapsing-remitting adult incident patients with at least two years of follow-up (N = 8,045)

Almost all patients (93.0%) were admitted at least once to the hospital for MS-related purposes during the study. Most patients visited a general practitioner (99.5%), a dentist (79.3%), an ophthalmologist (72.4%), and most female patients visited a gynecologist (62.4%). Most HA-RRMS patients also visited other healthcare professionals such as a nurse (86.1%) and a physiotherapist (73.4%). In addition, the majority of patients had several types of blood tests (ex: 98.4% had a complete blood count), an MRI (93.3%) and an ophthalmological exam (77.0%). Finally, the majority of patients used medical devices (87.0%) and had some of their transportation (to and from a place of care) covered by the NHI (67.8%).

4.2. Costs of HA-RRMS patients

Of the 9,596 incident patients, 7,956 (83.0%) had at least two years of follow-up and cost data which could be used. The results of the cost analysis are based on these patients.

Throughout the study period, the mean annual cost per HA-RRMS patient was €29,813 (SD €13,266) (). Three-quarters of the cost were incurred by only two items: drugs (40.0% of all costs, €11,932 per patient) and hospital care (32.7%, €9,753). Among the 3,024 patients who benefited from a disability pension, the mean annual cost of the was €7,168, corresponding to €2,724 per study patient (9.1% of all costs). Likewise, among the 3,807 patients who took some sick leave, the mean annual cost amounted to €1,956, corresponding to €936 per study patient (3.1% of the overall cost). Outpatient department visits and procedures represented 3.6% of the total costs (€1,088). Notably, primary and secondary care visits, and other medical professional visits (mostly nurse and physiotherapist visits) represented 0.9% (€254) and 3.1% (€911) of the cost, respectively.

Table 3. Cost of highly active relapsing-remitting adult incident patients with at least two years of follow-up and usable cost data (N = 7,956)

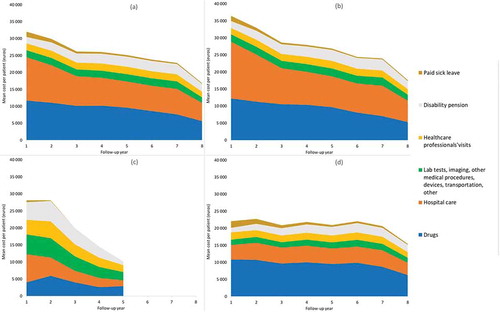

During the first year after inclusion, healthcare resources used, their distribution, and their proportion in the total cost were different than during the whole study follow-up (, ). During the first year, the total cost was €2,246 higher (€32,059 [SD €15,212]), the hospital care costs (40.0% of all costs) were €3,086 higher, and outpatient department visits and procedures were €135 lower than throughout the whole study follow-up. Besides, paid sick leave allowances were €638 higher and disability pensions were €830 lower the first year of the study. However, drug costs remained roughly the same over the study years.

Figure 1. Mean annual cost per highly active relapsing-remitting adult incident patient with at least two years of follow-up and usable cost data (N = 7,956), in all patients and by inclusion criterion, by large category of items

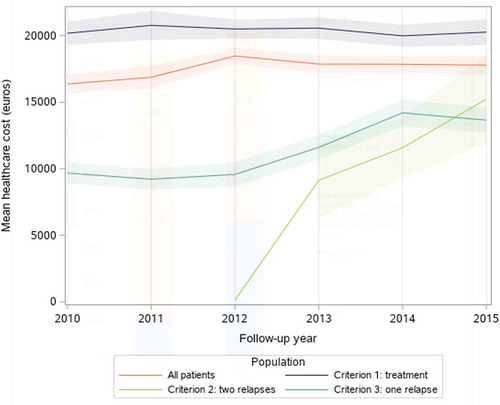

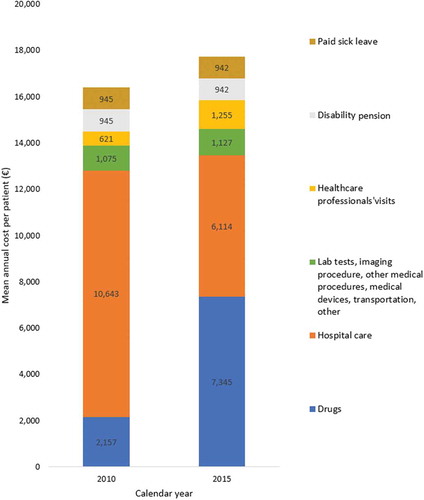

The mean annual cost per patient continuously decreased over time throughout the study to reach €16,850 during the eighth year after inclusion (only 829 patients were followed-up for eight years, therefore this result should be interpreted with caution) (). The mean annual cost per incident patient increased over the calendar years (). The fastest increase occurred between 2010 and 2012 (from €16,372 to €18,476), then remained stable (around €17,800) until 2015.

Figure 2. Mean annual cost per calendar year per highly active relapsing-remitting adult incident patient with at least two years of follow-up and usable cost data (N = 7,956), in all patients and by inclusion criterion, with 95% confidence intervals

Between 2010 and 2015, the cost per patient increased by 9%. Drugs increased by €5,188 and healthcare professionals’ visits by €635 (including a €522 in outpatient department visits and medical procedures) (). Meanwhile, the cost of hospital care decreased by €4,529. Examining the overall cost by inclusion criterion, we found that during the whole study follow-up, the mean annual cost per patient was higher for patients identified with criterion 1 (treatment) than with criterion 2 (two relapses) and criterion 3 (one relapse) (€32,534, €28,316, and €23,568, respectively).

Figure 3. Mean annual cost per highly active relapsing-remitting adult incident patient with at least two years of follow-up and usable cost data, in 2010 (N = 1,097) and 2015 (N = 1,258)

Likewise, during the first year after inclusion, the mean cost per patient was higher for criterion 1 patients than for criterion 2 patients and criterion 3 patients (€36,451, €28,116, and €22,071, respectively). The gap between the cost incurred by patients with criterion 1 and criterion 3 patients reduced over time (). The cost for criterion 2 patients rapidly declined over time but was based on a limited number of patients (139) and over a shorter follow-up period (five years).

Over 2010–2015, the cost of criterion 1 patients was stable (around €20,400) and of criterion 3 patients increased between 2010 (€9,677) and 2014 (€14,201). As for the cost of criterion 2 patients, its increased overtime to reach the cost of criterion 3 patients in 2015. It is important to note that in those annual figures, some patients have less than a year of expenditure (e.g. patients included in July 2010 only contribute six months to the 2010 cost estimate). Consequently, the calendar cost of incident patients is lower than the cost of the first year of follow-up (which is based on the first twelve month of expenditure).

5. Discussion

Between 2010 and 2017, among the 7,956 HA-RRMS incident adult patients included over 2010–2015 with at least two years of follow-up and usable healthcare cost in the French General health insurance Scheme, the mean annual cost of HA-RRMS patient healthcare, disability pension and paid sick leave was estimated to be €29,813 per patient. Drugs accounted for 40% of the cost, hospital care 33%, disability pensions 9%, and all healthcare professionals visits 8%. The cost was €2,246 higher during the first year after study inclusion (with a €3,086 increase in hospital care cost and €638 in paid sick leave but an €830 lower disability pension) than during the whole study period. During the first year after inclusion, the cost was €8,335 and €14,380 lower in patients with inclusion criterion 2 (two relapses) and criterion 3 (one relapse) than criterion 1 (treatment), respectively. Finally, the mean cost of HA-RRMS incident patient increased by €1,444 between 2010 and 2015, with a €5,188 increase in drug-related expenditures and a €634 increase in healthcare professionals’ visits expenditures, but a €4,529 decrease in hospital care expenditures.

We estimated the annual cost of HA-RRMS patients to be close to €30,000. In France, three studies have assessed cost of MS patients around the same period as our study [Citation10,Citation12,Citation22]. The first one, based on the same database as our study, estimated that, in 2013, the mean cost of MS patients was €11,900 [Citation12] vs €26,859 in our study for HA-RRMS patients. The second one, carried out in 2014, based on a regional MS registry and healthcare claims data on 2,166 patients, estimated the average total annual direct cost of MS to be €15,158 [Citation22] vs €28,013 in our study. The third one, a 2015 study based on a patient questionnaires and with 61% of the 491 study patients with relapsing-remitting MS estimated direct healthcare cost among MS patients to be €21,800 [Citation10]. However, it includes patient co-payments, out-of-pocket costs, services and informal care, and excludes sick leave and disability pension. Thus, this estimate cannot directly be compared with our results. With that said, we can infer that, in France, the cost of HA-RRMS patients is about twice that of MS patients. MS therapeutic management is similar between high-income countries [Citation23] yet it is hard to compare healthcare costs studies carried out in France to those in other countries due to the specificities of the French NHI. In fact, a 2009 study performed on a commercial US claims database and Medicaid found a mean cost (excluding DMT costs) of MS patients with high relapse activity (two relapses or more a year) of 26,800 USD which was about twice that of MS patients [Citation11]. In a recent Italian population-based study, healthcare costs of MS treated patients were estimated around €10,000 per year [Citation24].

MS therapeutic management is similar between high-income countries [Citation23] yet it is hard to compare healthcare costs studies carried out in France to those in other countries due to the specificities of the French NHI. In fact, a 2009 study performed on a commercial US claims database and Medicaid found a mean cost (excluding DMT costs) of MS patients with high relapse activity (two relapses or more a year) of 26,800 USD which was about twice that of MS patients [Citation11].

The large contribution of drugs (40%) and hospital care (33%) in HA-RRMS patients found in our study is also observed among MS patients in France (43% [Citation21] and 47% [Citation12] for drugs, 10% and 23% for hospital care). The large share of treatment costs in the total direct MS-related costs are also found in international studies based on patient surveys in Europe and Canada [Citation9,Citation13,Citation25], and in systematic review of US-based studies [Citation26].

About 20% of incident HA-RRMS patients aged 60 years or lower were disability pension beneficiaries at inclusion, comparable to the fraction of French prevalent MS patients [Citation12].

During the first year, the total cost was 8% higher than during the whole period and the distribution of the cost among the items was different. Over time, the total cost decreased, which could be interpreted as a sign of the effectiveness of the treatments in preventing relapses and hospital admissions and in lessening the number of healthcare professionals ‘visits.

Whereas drugs were the most expensive item during the study, followed by hospital care, the reverse was true during the first year. This is probably explained by intensive healthcare management to handle relapses, diagnostic procedures, and initiation of new treatments at the hospital. Indeed, during the study, 70% of HA-RRMS patients initiated a high efficacy treatment: 31% natalizumab (hospital-dispensed infusion) and 39% fingolimod (oral drug requiring specific monitoring at initiation). HE DMTs are expensive and need to be taken on a continuous, life-long basis, resulting in substantial healthcare costs over the patient’s lifetime. The cost of fingolimod acquisition alone was €24,842 according to Chevalier et al. [Citation27] and €17,745 according to Lefeuvre et al. The cost of natalizumab acquisition was €19,052 and the cost of one-day hospitalization for its dispensing was €3,950 [Citation12]. However, effective treatments that reduce relapse frequency and prevents progression, and can be dispensed outside of hospitals can eventually reduce the overall cost of MS.

In addition, the cost of paid sick leave is higher during the first year, likely due to the inability to work during the relapses and to go to the hospital.

Finally, fewer patients benefited from a disability pension during the first year, probably because as the disease progresses fewer patients are able to work full time and more patients claim the pension.

The cost of HA-RRMS incident patients increased between 2010 and 2012 then it was stable until 2015. As fingolimod became available in December 2011 in France, more patients either initiated a fingolimod (and were included in the study) or switched from natalizumab to fingolimod. The variation of costs of RRMS patients over years was also found in a 20-year cohort study with an increase annual cost of 11% after the introduction of tablets in 2011 [Citation28]. Fingolimod requires one hospitalization for the initial dispensing while natalizumab required a hospitalization for every dispensing. Indeed, the decline in the cost of hospital care (which includes the cost of hospital-dispensed drugs and drug dispensing) between 2010 and 2015 is compensated by the increase in (pharmacy-dispensed) drugs. The increase in the cost of outpatient department visits and medical procedures is probably due because some neurologist visits which were taking place during hospital stays in 2010 were held as outpatient visits in 2015. Moreover, as reported by Moccia et al., the healthcare organization can have an impact on the cost [Citation24].

The total cost was highest for patients included with criterion 1 (treatment), intermediate for those with criterion 2 (two relapses) and lowest for those with criterion 3 (1 relapse), during the first year after inclusion and over calendar years. The difference in the total cost between criterion 1 and criterion 3 patients decreased over the follow-up period, as patients started to be managed the same way (45% of criteria 2 and 3 patients initiated an HE DMT during the study). Throughout the study, Criterion 2 patients received a less expensive drug treatment. Hence, their total cost was lower than that of the other patients. We would expect these patients to incur higher hospital costs. This could reveal a patient selection bias due to our algorithm may not fully correspond to HA-RRMS patients.

One limitation is the absence of clinical information (such as MS relapses or measure of the disability severity), laboratory tests and imaging procedures results (e.g. MRI results) in the database. Besides, there is no ICD-10 code for HA-RRMS. Therefore, we developed an algorithm to identify HA-RRMS patients based on reimbursement of HE DMTs and frequency of relapses. While our definition of a relapse was based on a validated US claims-based algorithm [Citation11] and two recent studies confirmed that an algorithm can be used to identify relapses in the SNDS [Citation29,Citation30], our new algorithm to identify HA-RRMS patients should be validated in other studies. This proxy can induce a selection bias, questioning the accuracy of some HA-RRMS ‘diagnoses.’ Clinical and MRI criteria have recently been proposed to define HA-RRMS patients, however without consensus at present [Citation4].

In addition, our study disregards the cost of informal care (which is high in MS [Citation31]), productivity loss, and out-of-pocket drugs costs (which exists despite MS is fully covered by NHI [Citation18]).

France has a unique and performant health insurance system [Citation32], with comprehensive population coverage and low and regulated healthcare prices compared to other countries. Therefore, the cost found in this study only applies to France and, as other drugs were launched since we conducted our study, to that period. This study’s main strength is the very high population coverage (around ¾ of the population). As there is no evidence of differences in patient characteristics and healthcare management between schemes, our results are likely to be generalizable to the whole HA-RRMS French population. The study’s other assets are the 8-year follow-up and the absence of patient participation bias given that the data are routinely collected for reimbursement purposes and not specifically for this study.

6. Conclusion

In France, in 2010–2017, the annual cost of 2010–2015 incident HA-RRMS adults was close to €30,000 per patient (approx. 36,400 USD), which is twice as high as the previously reported cost of MS patients. Based on this study, HA-RRMS patients would represent around 8% of MS patients. The cost was higher during the first year of HA-RRMS than for during the whole follow-up, due to increased hospital admissions and paid sick leave. Effective treatments that reduce relapse frequency and prevents progression could reduce the cost of MS. As new therapies become available, cost of HA-RRMS patients should be monitored over time.

*Medical device examples: Technical aids for walking; wheelchair, Orthopedic shoes; Transfer device Medical bed and accessories, electrical neurostimulator, ventilation equipment.

Authors’ contributions

AK, MP, EP, FR, BvH and OV contributed significantly to the conception and the design of the work; FR contributed significantly to the data acquisition. All authors contributed significantly to analysis, and data interpretation; JLT have drafted the work and OC and JLT revised it. All authors approved the most recent submitted version (and any substantially modified version that involves the author’s contribution to the study) AND have agreed to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Consent for publication

The SNIIRAM contains comprehensive individualized and anonymous data on all healthcare expenditures reimbursed by the French NHI. Thus, no consent for publication was needed.

Declaration of interest

OV is independent expert who received fees for participating in the scientific committee of the study and an employee of Merck S.A.S., an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. MP, BvH and EP are employees of Merck S.A.S., an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. JLT and FR are employees of the CRO HEVA in charge of data extraction and analyze. AK is an independent expert who received fees for participating in the scientific committee of the study. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been approved by the Committee for research, studies and evaluations in the field of health (Comité d’expertise pour les recherches, les études et les évaluations dans le domaine de la santé, CEREES). The CEREES has been replaced by the CESREES in 2020. See process at https://www.health-data-hub.fr/utilisateur-de-donnees. Raw data have been made available after acceptance from the French data protection and Ethic authority (Comité National d’informatique et Liberté, CNIL): CNIL: decision DR-2018-099 and authorization number 918,111. In accordance with the regulations in force, patient consent was not necessary because this study uses anonymized secondary data, there was a public interest in assessing, for the first time, the HA-RRMS population in France, their therapeutic management and the cost of the HA-RRMS patients, and the protection of patients’ rights and freedom were guaranteed.

Key points for decision makers

We identified 9,596 patients with highly active relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (HA-RRMS) in the main health insurance scheme, of which 7,956 where followed-up for at least two years and had usable cost data.

From the national health insurance’s perspective, the total cost for the care of HA-RRMS patients (all diseases and injuries combined) was close to €30,000 per year and drugs and hospital care made up almost ¾ of this cost.

The total costs increased by 9% between 2010 and 2015, with a switch from hospital care expenditure to drug-related and outpatient department visits and procedures expenditures.

Reviewers disclosure

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed consulting with a number of MS pharma. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Availability of data and material

Data from the National Health data system in France (Système National des Données de Santé, SNDS) are publicly available (https://www.snds.gouv.fr/SNDS/Processus-d-acces-aux-donnees) after acceptance from the French data protection authority (Comité National d’informatique et Liberté, CNIL). The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from co-author FR on reasonable request. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Roux J, Guilleux A, Lefort M, et al. Use of healthcare services by patients with multiple sclerosis in France over 2010–2015: a nationwide population-based study using health administrative data. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019;5(4):205521731989609. .

- Foulon S, Maura G, Dalichampt M, et al. Prevalence and mortality of patients with multiple sclerosis in France in 2012: a study based on French health insurance data. J Neurol. 2017;264::1185–1192.

- Multiple sclerosis international federation. Atlas of MS 2013 - Mapping multiple sclerosis around the world [Internet]. London, UK: Multiple sclerosis international federation; 2014. 28. Available from: http://www.msif.org/includes/documents/cm_docs/2013/m/msif-atlas-of-ms-2013-report

- Iacobaeus E, Arrambide G, Amato MP, et al. Aggressive multiple sclerosis (1): towards a definition of the phenotype. Mult Scler. 2020 Jun 12;26(9):1352458520925369. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520925369.

- Arrambide G, Iacobaeus E, Amato MP, et al. Aggressive multiple sclerosis (2): treatment. Mult Scler. 2020 Jun 12;26(9):1352458520924595. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520924595.

- Díaz C, Zarco LA, Rivera DM. Highly active multiple sclerosis: an update. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:215–224.

- Scolding N, Barnes D, Cader S, et al. Association of British Neurologists: revised (2015) guidelines for prescribing disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. Pract Neurol. 2015;15:273–279.

- Fattore G, Lang M, Pugliatti M. The Treatment experience, burden, and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) study - measuring the socioeconomic consequences of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012;18:5–6.

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden, and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in multiple sclerosis: the costs and utilities of MS patients in Canada. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2012;19:e11–25.

- Lebrun-Frenay C, Kobelt G, Berg J, et al. European multiple sclerosis platform. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for France. Mult Scler. 2017;23:65–77.

- Raimundo K, Tian H, Zhou H, et al. Resource utilization, costs and treatment patterns of switching and discontinuing treatment of MS patients with high relapse activity. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:131.

- Lefeuvre D, Rudant J, Foulon S, et al. Healthcare expenditure of multiple sclerosis patients in 2013: a nationwide study based on French health administrative databases. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin [Internet]. 2017 3, [cited 2017 Oct 6]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5600306/

- Kobelt G, Thompson A, Berg J, Group the MS, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler J [Internet]. SAGE PublicationsSage UK: London, England; 2017 [cited 2020 Sep 11]; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1352458517694432?icid=int.sj-related-articles.similar-articles.16

- Tuppin P, Rudant J, Constantinou P, et al. Value of a national administrative database to guide public decisions: from the système national d’information interrégimes de l’Assurance Maladie (SNIIRAM) to the système national des données de santé (SNDS) in France. Revue d’Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique. 2017;65:S149–67.

- Bezin J, Duong M, Lassalle R, et al. The national healthcare system claims databases in France, SNIIRAM and EGB: powerful tools for pharmacoepidemiology. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:954–962.

- Derwenskus J. Current disease-modifying treatment of multiple sclerosis. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78:161–175.

- Centre des liaisons européennes et internationales de sécurité sociale, République Française. The French Social Security System. I-Health, maternity, paternity, disability, and death [Internet]. Vous informer sur la protection sociale à l’international. 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.cleiss.fr/docs/regimes/regime_france/an_1.html

- Heinzlef O, Molinier G, van Hille B, et al. Economic burden of the out-of-pocket expenses for people with multiple sclerosis in France. Pharmaco Economics Open [Internet]. 2020 cited 2020 Sep 24. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-020-00199-7.

- Chevreul K, Berg Brigham K, Durand-Zaleski I, et al. France: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2015;17:1–218,xvii.

- Arrêt maladie [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 15]. Available from: https://www.ameli.fr/assure/remboursements/indemnites-journalieres/arret-maladie

- Pensions d’invalidité [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 15]. Available from: https://www.ameli.fr/entreprise/vos-salaries/montants-reference/pension-invalidite

- Detournay B, Debouverie M, Pereira O, et al. Economic burden of multiple sclerosis in France estimated from a regional medical registry and national sick fund claims. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;36:101396.

- Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24:96–120, SAGE Publications Ltd STM

- Moccia M, Tajani A, Acampora R, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs for multiple sclerosis management in the Campania region of Italy: comparison between centre-based and local service healthcare delivery. PLOS ONE. 2019 Sep 19;14(9):e0222012. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222012.

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from five European countries. Mult Scler. 2012;18:7–15.

- Adelman G, Rane SG, Villa KF. The cost burden of multiple sclerosis in the United States: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Econ. 2013;16:639–647.

- Chevalier J, Chamoux C, Hammès F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis: a French societal perspective. Ramagopalan SV, editor. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0150703.

- Petruzzo M, Palladino R, Nardone A, et al. The impact of diagnostic criteria and treatments on the 20-year costs for treating relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;38:101514.

- Bosco-Lévy P, Debouverie M, Brochet B, et al. Validation d’un algorithme complexe d’identification de poussées dans la sclérose en plaque (SEP) à partir du Système National des Données de Santé (SNDS). Revue Neurologique [Internet], s81–2, Elsevier; 2020;176 (Suppl):S81-S82. [cited 2020 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.em-consulte.com/article/1387114/alertePM

- Vermersch P, Suchet L, Colamarino R, et al. An analysis of first-line disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis using the French nationwide health claims database from 2014–2017. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46:102521.

- Paz-Zulueta M, Parás-Bravo P, Cantarero-Prieto D, et al. A literature review of cost-of-illness studies on the economic burden of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;43:102162.

- World Health Organization, editor. The world health report 2000: health systems: improving performance. Geneva: WHO; 2000.