ABSTRACT

Introduction

The DAPA-HF study has shown that dapagliflozin added to standard treatment reduced the risks of worsening of heart failure or cardiovascular death compared to placebo.

Objectives

To evaluate the cost- utility of dapagliflozin in combination with standard treatment compared to standard treatment alone for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction from the perspective of the Colombian health system.

Methods

A Markov model using information from the DAPA-HF study was adapted to the Colombian setting. Health states considered symptom score, and transient health states were included to assess the incidence of consultations and hospitalizations for heart failure. The time horizon was 5 years and a 5% discount rate was applied. The costs were expressed in US dollars of 2020 (1 USD =$3,693.36 COP).

Results

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of the intervention compared to standard treatment was USD $5,946 per quality adjusted life year gained. The ICER remained below the cost-effectiveness threshold in sub-group analyses. 97% of sensitivity analysis simulations showed an ICER below the cost-effectiveness threshold.

Conclusion

From the perspective of the analysis, the addition of dapagliflozin to standard treatment is a cost-effective option in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in Colombia.

1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a clinical syndrome that is composed of symptoms and signs produced by low cardiac output or elevated intracardiac pressure as a result of structural and functional abnormalities of the heart, and has been classified based on the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) [Citation1]. A HF with reduced LVEF (≤40%) is identified as HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF [Citation2]. The main symptoms of HF are dyspnea, congestive symptoms, and arrhythmias [Citation3,Citation4] which have a major impact on the quality and life expectancy of those who suffer it

Based on international references, it has been estimated that the prevalence of HF in Colombia could be as high as 2.3%, indicating that about 1,097,201 people suffer from this condition. The frequency of the disease increases with age. An incidence of 2 per 1,000 for those between 35–64 years of age and of 12 per 1,000 for those between 65–94 years has been stated. In 2012, the mortality rate from this pathology was 5.54 per 100,000 people [Citation5,Citation6].

Heart failure has a significant impact on the health system in terms of burden of disease and economic impact. In Latin America, it has been estimated that it has a hospitalization rate of 31 to 35%, an in-hospital mortality of 11.7%, and the impact may be greater in patients with reduced ejection fraction [Citation7].

The goal of treatment is to improve the symptoms, as well as quality of life and life expectancy. Another objective is to reduce the frequency of hospitalizations that are related to the progression of the disease and which increase the risk of death [Citation8]. For patients with HFrEF, drug treatment is based on the combination of a neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi), beta-blocker (BB), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) [Citation1,Citation9] and an SGLT2 inhibitor (iSGLT2), the last drug being included in the most recent heart failure management guidelines [Citation10]. The DAPA-HF study showed that dapagliflozin (10 mg taken once daily) added to standard treatment reduced the risks of hospitalization for heart failure by 30% and cardiovascular death by 18% compared to placebo [Citation11].

Taking into account the value that cost-effectiveness analyses can produce for decision makers, since they consider the benefits and costs related to a new health technology or management strategy, the objective of this analysis was to evaluate the incremental cost-effectiveness of the addition of dapagliflozin to the standard treatment compared to the standard treatment in the treatment of HFrEF, from the perspective of the Colombian health system.

2. Methods

An economic model was adapted, whose main result was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) expressed as the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. This outcome allowed the impact of technologies on health-related quality of life to be captured. Additionally, this measure is recommended by the Institute for Technological Evaluation in Health (IETS) for economic evaluations in our environment [Citation12]. For Colombia, a cost-effectiveness threshold has been adopted which is between 1 GDP (USD $5,710) and 3 GDP per capita (USD $17,130), taking the provisional data reported by the Central Bank in 2019 into consideration [Citation13]. The intervention is considered to be ‘cost-effective’ if the ICER is below 1 GDP per capita and as ‘potentially cost-effective’ if it is less than 3 times the GDP per capita.

2.1. Target population

The target population was defined as adult patients with a diagnosis of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). The population that was modeled is aligned with the eligibility criteria defined in the DAPA-HF study [Citation11]. An overall analysis and an analysis of subgroups were performed, among which the following were prioritized: with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), without DM2, ≤ 65 years, and > 65 years. lists the characteristics of the population considered in the economic model. These characteristics influenced event calculation and initial patient distribution among health states. Overall and subgroup baseline characteristics were extracted from the available reports of DAPA-HF [Citation11,Citation14,Citation15] and directly calculated from individual data.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the DAPA-HF study population and relevant subgroups [Citation11,Citation14,Citation15]

2.2. Intervention and comparators

The technology defined as the intervention in this economic evaluation is dapagliflozin added to the standard treatment. The recommended dose is 10 mg per day administered orally [Citation16]. The comparator defined for this evaluation was the standard treatment which corresponds to a weighted comparator of the different treatment options used in HFrEF, which include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers(ARB), ARNi, MRA and BB. In , the proportion of use of the drug groups that make up the standard treatment according to the Recolfaca registry is shown [Citation17].

Table 2. Model parameters

2.3. Time horizon, perspective and discount rate

The perspective applied was that of the third-party payer, which in the case of Colombia is the General System of Social Security in Health (SGSSS). The time horizon considered in the economic evaluation was 5 years in the base case. This time horizon was considered sufficient to observe the differences between the intervention and the standard treatment. A time horizon of 5–10 years is consistent with other economic evaluations carried out in heart failure within the local context [Citation18,Citation19]. In the sensitivity analyses, the time horizon was changed to ten years and the life expectancy. For the life expectancy analysis, a time horizon of 16 years was considered, which corresponds to the life expectancy reported by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) for an age of 68 years [Citation20]. For the base case, a 5% discount rate was used for both costs and health outcomes [Citation12].

2.4. Model

The structure and assumptions of the DAPA-HF model previously developed for the cost-effectiveness analysis of the health technology in other regions were adopted [Citation21]. The cost-effectiveness evaluation was carried out using a Markov model (). The Markov approach in heart failure analysis has been used previously [Citation22,Citation23] since the progression of the disease can be described by a small number of health states. Cycle length was defined as 1 month to keep consistency other previously developed technology assessments such as TA388 andTA267 [Citation22,Citation23]. Heart failure is modeled through the transition between different health states characterized by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Total Symptom Score (KCCQ TSS). These health states are subsequently stratified in accordance with the presence of DM2. The progression of patients through health states is based on transition probabilities that vary over time and are estimated through adjusted survival curves. Using generalized estimation equations, the incidence and recurrence of visits to the emergency room or hospitalizations for heart failure are calculated. Patient mortality is modeled using parametric survival equations that describe mortality from all causes, and independent equations are used to estimate the proportion of deaths from cardiovascular causes, which are associated with additional costs. The model considered three types of transient health states: first or recurrent hospitalization for heart failure (HHF), first or recurrent urgent heart failure visit (UHF) and adverse events. Whenever patients present these events, their cost and utility payoff changed for one cycle and afterward returned to the original values.

2.5. Model inputs

2.5.1. Progression of the disease

The probabilities of transition between the health states, which were defined as quartiles of the KCCQ TSS, were obtained using monthly transitions. In the DAPA-HF study [Citation11], KCCQ TSS trends showed an inflection point at the fourth month after baseline. Consequently, an independent transition matrix was used for the first four months, and a second matrix from month five onward. In the clinical study, it was observed that the effect of the treatment was statistically significant in the change of the KCCQ TSS with respect to the baseline . The transitions have a multinomial probability, which was combined with a Dirichlet prior distribution using Gibbs sampling to obtain the posterior probability distribution in the transition matrix between KCCQ TSS states [Citation24]. The probabilities of transition between the health states, defined as the quartiles of the KCCQ, are reported in the Supplementary Material (Table S1).

2.5.2. Mortality and hospitalization events due to heart failure

Parametric survival equations adjusted for information at patient level from the DAPA-HF study as well as to key patient subgroups [Citation11] were used to estimate mortality due to all causes and to cardiovascular mortality. The Weibull distribution was used in the base case as it provides more plausible estimates for long-term survival [Citation25].The life tables were adjusted taking into account the proportion of cardiovascular deaths out of the total deaths reported for Colombia by the World Health Organization (WHO). This proportion is applied to the mortality data reported by DANE in order to define non-cardiovascular mortality, which is subsequently converted into probability.

The incidence of HHF and UHF was estimated through a generalized negative binomial equation in order to capture both first and recurrent events. These equations were adjusted for the total population and the subgroups of the DAPA-HF study [Citation11] to produce appropriate predictions of events . Two sets of equations were generated, one adjusted to the frequency of events due to the use of dapagliflozin and adjusted to relevant patient subgroups, and the other using a single equation that is adjusted to the characteristics of the patients which can modify the outcome. Incidence of HHF was thus stratified by patient subgroup. This was not possible for UHF given the limited number of observed events.

2.5.3. Health-related quality of life

An utility was assigned to each of the model’s states, including transient events, which is weighted by the proportion of patients that remain in each state to calculate the accumulated QALYs during the time horizon. The utilities were obtained from information collected in the DAPA-HF study [Citation11]. The authors of the model developed mixed-effects linear regressions to predict the utility values taking into account the 5-level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5 L) questionnaires used during the study. The mixed-effects models were used to consider the correlation of time and between patients and were adjusted according to the time elapsed since the baseline, gender, KCCQ TSS quartile, the presence of DM2, BMI and age. The EQ-5D-5 L responses were mapped to the 3-level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-3 L) by applying the mapping function developed by Hout et al [Citation26] in accordance to current NICE technology assessment guidelines. Responses were converted to utility index scores using United Kingdom preferences for EQ-5D health states, using the trade-off method described in the Dolan study [Citation27].

The model incorporates the impact of HHF and UHF events, and of adverse effects on the baseline utility, which is why they are applied as decreases. In a given cycle, a proportion of the modeled cohort will incur utility decreases related to adverse events, depending on treatment and the incidence of hospitalization and emergency events. The utility values considered in the model are shown in .

2.5.4. Acquisition costs

For the intervention, the acquisition costs of dapagliflozin and the standard treatment were taken into account. For those receiving dapagliflozin, a constant discontinuation rate was applied in each cycle of the model, which was obtained from the DAPA-HF study [Citation11]. After discontinuation, patients were modeled as patients receiving standard treatment, so the risks of events, the costs and the utilities correspond to those of the control group.

In the model, when patients discontinue dapagliflozin, only the cost of standard treatment is applied to them. Medication doses were based on the clinical practice guidelines for heart failure [Citation28] and were validated by clinical experts. Among the ACE inhibitors, only enalapril was taken into account; among the ARBs, candesartan, losartan and valsartan were considered; and among the MRAs, spironolactone and eplerenone. The participation of the active ingredients in each subgroup was defined by the clinical experts. The prices of the drugs were obtained from the Sistema de información de precios de medicamentos (SISMED) report for the first semester of 2020 [Citation29] and Circular 10 of 2020 [Citation30]. shows the annual costs of the intervention and its comparator. Details regarding the doses and prices of the drugs can be seen in the Supplementary Material (Table S2).

2.5.5. Costs of health conditions and adverse events

For the modeled health states and transient health events, a cost was assigned that in most cases was obtained from previous studies developed in Colombia. The bottom-up methodology was used only for events regarding outpatient care and emergency consultation for heart failure so that with the help of experts cost-generating events were identified, and using tariffs and local price reports a valuation was carried out in order to obtain the total cost of caring for the event. The costs of consultations, laboratories and procedures were obtained from the ISS tariff and an increase of 30% was applied following the IETS recommendations. The costs of the drugs were obtained from the latest SISMEDprice report and the price regulation circulars. Details regarding the use of resources and costs of events that were not obtained from the literature can be seen in the Supplementary Material (Table S3). Health costs are entered as annual costs, and transient events such as HHF, UHF, or cardiovascular death are applied only in the cycle where the events occur for the first time. In the base case, adverse events were not taken into account, but they were included in a sensitivity analysis. For cardiovascular death, we extrapolated the cost of fatal myocardial infarction obtained from a local study [Citation31]. Considering that cardiovascular death due to HF may have a different cost, we constructed a specific sensitivity scenario was constructed reducing this cost to zero.

In the model, the costs related to adverse events take into account the incidence of the specific event depending on the treatment received in each cycle. The probabilities of adverse events were evaluated as a function of the number of observed events and the patient’s time at risk. In patients who discontinue dapagliflozin, the risk of adverse events of the placebo group in the DAPA-HF study was applied [Citation11]. Taking into account that the study did not find significant differences in the frequency of adverse events, these were not considered in the base case, but rather as a sensitivity analysis. The adverse effects automatically considered in the model were volume depletion, renal events, hypoglycemic events, diabetic ketoacidosis, and amputation. The annual probability of these events for the intervention and the comparator is shown in . The costs of adverse events were mostly obtained from the literature and were adjusted for 2020 prices using the Consumer Price Index (CPI)published by DANE [Citation32]. For diabetic ketoacidosis and amputation events, the cost was calculated using the bottom-up methodology so that the use of resources was quantified with the help of experts and the assessment was carried out taking local tariffs into account (Supplementary Material, Table S3). shows the costs of the states, transient health events, and adverse drug events.

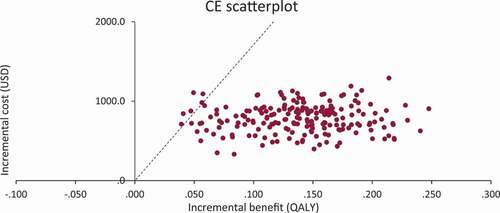

2.6. Sensitivity analysis

A deterministic and a probabilistic sensitivity analysis were carried out using Monte Carlo simulations. The deterministic sensitivity analysis is summarized in a tornado diagram that shows how changing certain variables modifies the ICER with respect to the base case. In the probabilistic sensitivity analysis, the impact of the uncertainty of the model variables on the results is evaluated. The values of the different variables are sampled from the selected distributions. Costs were distributed using gamma distributions, patient characteristics with normal distributions, and proportions with beta distributions. Distribution parameters were estimated from mean and standard error for each variable (). As part of the analysis, the scatterplot for the cost-effectiveness plane and the acceptability curve has been generated.

Table 3. Results of the base case

3. Results

3.1. Base case

shows the results of the base case taking into account the total population and the different analysis subgroups. For all cases, dapagliflozin plus standard treatment would be a cost-effective alternative compared to the standard treatment, since the ICER is between 1 and 2 GDP per capita. Although the costs of the intervention are related to increases in acquisition costs, it can be seen that the costs of emergencies and hospitalization and deaths from cardiovascular causes are lower. The higher monitoring costs are related to having a greater number of patients who survive with the intervention than with the comparator. The best ratio in terms of cost-effectiveness is observed in the subgroups of patients with DM2 and in those over 65 years of age.

Table 4. Cost effectiveness results in specific subgroups

3.2. Sensitivity analysis

3.2.1. Specific sensitivity analysis

When considering the data from the Recolfaca registry, an increase in ICER is observed, which is related to the lower proportion of patients with DM2 compared to that of patients in the DAPA-HF study [Citation11]. Adverse reactions do not substantially modify the results of the base case. When considering the life expectancy to model, the ICER drops below 1 GDP per capita. This change is mainly related to an increase in QALYs gained over time. When considering cardiovascular death cost as zero, ICER was slightly higher but still withing the cost-effectiveness threshold. The results of the specific scenarios are reported in the Supplementary Material (Table S4).

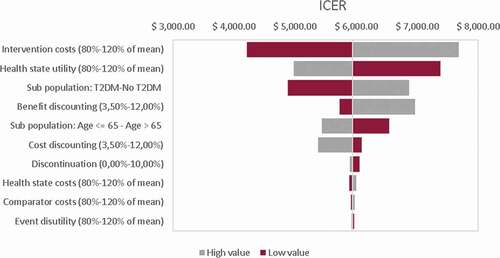

3.2.2. Deterministic sensitivity analysis

According to the tornado diagram, the results are robust against changes in the variables within the established ranges, so the intervention remains a cost-effective alternative. The variables that have the greatest impact on the results are the analysis time horizon, the costs of the intervention and the proportion of patients with DM2.

3.2.3. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was run with 200 iterations. According to the cost-effectiveness plane, it can be seen that most of the simulations are below the WTP threshold. According to the acceptability curve (see Supplementary Material, Figure S1), the probability that the intervention is cost-effective is 97% at a WTP of 3 GDP per capita.

4. Discussion

The base case results suggest that dapagliflozin in combination with standard treatment is a cost-effective intervention in the treatment of HFrEF compared to the use of standard treatment alone. In the analysis subgroups that were patients with HFrEF with and without diabetes, or older than 65 years and younger than 65 years, the intervention is also a cost-effective option compared to standard treatment. The results are related to an increase in QALY and a reduction in hospitalization costs and cardiovascular death. The results are robust against changes in the analysis parameters of the model.

Cost effectiveness studies evaluating dapagliflozin in HFrEF have been performed in several other regions where the costs of hospitalization and medical consultations are higher than in the local context. Dapagliflozin has been found to be likely cost-effective in the United Kingdom, Spain, Germany [Citation21,Citation33] and the United States [Citation34,Citation35]. This is the first study evaluating dapagliflozin in HFrEF in Colombia and it is showing consistent results with other evaluations.

In Colombia, other studies have been carried out evaluating the cost-effectiveness of pharmacological interventions in the treatment of HFrEF. In 2016, an analysis of sacubitril/valsartan compared to enalapril was published [Citation25]. The analysis horizon was life expectancy and an ICER of COP 39.5 million per QALY gained was estimated [Citation25]. As part of the development of the clinical practice guideline for heart failure, the cost-effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy associated with standard therapy was evaluated in comparison with standard therapy for NYHA I–II and NYHA III–IV performance status. The incremental QALYs with the intervention were of the order of 0.57 and 0.77 in the models developed in the performance classes NYHA I–II and NYHA III–IV, respectively [Citation28]. It is important to mention these local studies not to directly compare them to this study, but to provide context of the efficiency of other technologies currently employed in Colombia.

Although the performance states in most of the cost-effectiveness models that have been developed for heart failure have been defined as the health states in the Markov model [Citation36], the authors of the present model developed a different approach due to the limitations previously identified with the NYHA states. One of them is related to the reproducibility and reliability problems that have been identified, and it is not so patient-centered [Citation37–39]. Another of the limitations in using the NYHA is related to long-term evaluation, as it does not allow the progression of the disease to be adequately modeled.

The findings of this economic evaluation reinforce the position of the main societies that include health personnel in charge of the management of patients with HFrEF, particularly the CCS (Canadian Cardiovascular Society) [Citation10], who included this medicine in the basic treatment of HFrEF patients due to its clinical benefits, low side effects and economic evaluations in different settings, which support its use and inclusion in the standard treatment of this pathology.

Because the efficacy information was based on the DAPA-HF study [Citation11] it was necessary to extrapolate this information to a horizon longer than 18 months. In Colombia, there is still no empirical estimate of the cost-effectiveness threshold and the estimate is the subject of numerous theoretical and methodological discussions, but for the purposes of interpretation 3 GDP per capita has been used as a reference. Another limitation is related to the fact that the EQ-5D preferences for health states from the United Kingdom were used for the utility measurements, which may not reflect the preferences of Colombian patients.

5. Conclusions

The results of this economic evaluation suggest that the use of dapagliflozin in combination with the optimal pharmacological treatment is cost-effective compared to the use of standard treatment, under the WTP threshold of the Colombian health system. The intervention remains a cost-effective option within the different analysis subgroups, obtaining a better cost-effectiveness ratio in patients with DM2 as comorbidity.

Author contributions

Y Gil-Rojas and P Lasalvia were responsible for the literature review, cost estimation and data analysis, as well as the conception and final revision of the manuscript. AG contributed to the conception of the study and final revision of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

Y Gil-Rojas and P Lasalvia report grants from AstraZeneca, during the conduct of the study. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (74.3 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2129–2200m.

- Bozkurt B, Coats AJ, Tsutsui H, et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the heart failure society of America, heart failure association of the European society of cardiology, Japanese heart failure society and writing committee of the universal definition o. J Card Fail. 2021;27(4):2021.

- Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and aetiology of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13(6):368–378.

- Chaudhry SP, Stewart GC. Advanced heart failure: prevalence, natural history, and prognosis. Heart Fail Clin. 2016;12(3):323–333.

- Gómez E. Capítulo 2. Introducción, epidemiología de la falla cardiaca e historia de las clínicas de falla cardiaca en Colombia. Rev Colomb Cardiol. 2015;23:6–12.

- Instituto Nacional de Salud - Observatorio Nacional de Salud. Primer informe observatorio nacional de salud - ONS: Aspectos relacionados con la frecuencia de uso de los servicios de salud, mortalidad y discapacidad en Colombia. Bogotá, D.C., Colombia: Imprenta Nacional de Colombia; 2011.

- Ciapponi A, Alcaraz A, Calderón M, et al. Burden of heart failure in Latin America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Española Cardiol. 2016;69(11):1051–1060.

- Bloom MW, Greenberg B, Jaarsma T, et al. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:1–19.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart failure society of Amer. J Card Fail. 2017;23(8):628–651.

- McDonald M, Virani S, Chan M, et al. CCS/CHFS heart failure guidelines update: defining a new pharmacologic standard of care for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(4):531–546.

- JJV M, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):1995–2008.

- Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud. Manual para la elaboración de evaluaciones económicas en salud. Bogotá: IETS; 2014.

- Banco de la República. PIB total y por habitante 2019(pr) a precios corrientes. 2020.

- JJV M, DeMets DL, Inzucchi SE, et al. The dapagliflozin and prevention of adverse‐outcomes in heart failure (DAPA‐HF) trial: baseline characteristics. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(11):1402–1411.

- Martinez FA, Serenelli M, Nicolau JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction according to age. Circulation. 2020;141(2):100–111.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Prescribing information: dapagfliflozina (farxiga) [internet]. 2020 [ cited 2020 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/202293s003lbl.pdf

- Saldarriaga C, Gómez J, Echeverría E Heart failure in Colombia: results form the RECOLFACA registry. Hear Fail 2019 [internet]. 2019. p. P2012. [cited 2021 Nov 07] Available from: https://esc365.escardio.org/presentation/193101?query=RECOLFACA https://esc365.escardio.org/presentation/193101?query=RECOLFACAttps://esc365.escardio.org/Congress/Heart-Failure-2019-6th-World-Congress-on-Acute-Heart-Failure/Poster-Session-4-Chronic-Heart-Failure-Epidemiology-Prognosis-Outcome/193101-heart-failure-in-colombia-results-form-the-recolfaca-registry

- Romero M, Arango CH. Analysis of cost effectiveness of the use of metoprolol succinate in the treatment of hypertension and heart failure in Colombia. Rev Colomb Cardiol. 2012;19:160–168.

- Atehortúa S, Senior JM, Castro P, et al. Cost-utility analysis of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for the treatment of patients with ischemic or non-ischemic New York heart association class II or III heart failure in Colombia. Biomedica. 2019;39(3):502–512.

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadísticas (DANE). Estimaciones del cambio demográfico: tablas de vida completas y abreviadas por sexo y área a nivel nacional 2018–2070 y departamental 2018–2050 [Internet]. 2020 [ cited 2020 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/estimaciones-del-cambio-demografico

- McEwan P, Darlington O, JJV M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin as a treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a multinational health-economic analysis of DAPA-HF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(11):2147–2156.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Technology appraisal guidance [TA267]: ivabradine for treating chronic heart failure. [internet]. 2012 [ cited 2020 Oct 17]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta267

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Technology appraisal guidance [TA388]: Sacubitril valsartan for treating symptomatic chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. 2016.

- Welton N, Sutton A, Cooper N, et al. Evidence Synthesis for Decision Making in Healthcare. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; New Jersey, United States. 2012.

- JJV M, Trueman D, Hancock E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan in the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Heart. 2018;104(12):1006–1013.

- Van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Heal. 2012;15(5):708–715.

- Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol Health States. Med Care. 1997;35(11):1095–1108.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la prevención, diagnóstico, tratamiento y rehabilitación de la falla cardíaca en población mayor de 18 años clasificación B, C y D. Guía completa No.53 [GPC en Internet]. Edición 1. Bogotá D.C. [Internet]; 2016 [ cited 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: http://gpc.minsalud.gov.co/

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (MSPS). Sismed - Sistema de información de precios de medicamentos. Reporte 2020. [Internet]; 2021 [ cited 2021 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.sispro.gov.co/recursosapp/app/Pages/PreciosdeMedicamentos-Circular2de2012Excel.aspx

- Ministerio de Salud y de la Proteccion Social. Circular 10 de 2020. Por la cual se unifica y se adiciona el listado de los medicamentos sujetos al régimen de control directo de precios, se fija su precio máximo de venta, se actualiza el precio de algunos medicamentos conforme al Índice de precios [Internet]. 2020 [ cited 2021 Apr 10]. Available from: http://minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/MET/circular-10-de-2020.pdf

- Mendoza F, Romero M, Lancheros J, et al. Financial burden of atrial defibrillation in Colombia. Rev Colomb Cardiol. 2020;27. 541–547.

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadísticas (DANE). Índice de precios al consumidor (IPC) - series de empalme, abril de 2020 [internet]. 2020 [ cited 2020 May 18]. Available from: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/precios-y-costos/indice-de-precios-al-consumidor-ipc

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Technology appraisal guidance [TA679]: dapagliflozin for treating chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. [internet]. 2020 [ cited 2021 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta679/documents/final-appraisal-determination-document

- Isaza N, Calvachi P, Raber I, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(7):e2114501.

- Parizo JT, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Salomon JA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin for treatment of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(8):926.

- Di Tanna GL, Bychenkova A, O’Neill F, et al. Evaluating cost-effectiveness models for pharmacologic interventions in adults with heart failure: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(3):359–389.

- Raphael C, Briscoe C, Davies J, et al. Limitations of the New York heart association functional classification system and self-reported walking distances in chronic heart failure. Heart. 2007;93(4):476–482.

- Gibelin P. An evaluation of symptom classification systems used for the assessment of patients with heart failure in France. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3(6):739–746.

- Bennett JA, Riegel B, Bittner V, et al. Validity and reliability of the NYHA classes for measuring research outcomes in patients with cardiac disease. Hear Lung J Acute Crit Care. 2002;31(4):262–270.

- González CJ, Walker JH, Einarson TR. Cost-of-illness study of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Colombia. Pan Am J Public Heal. 2009;26:55–63.

- TamayoD C, Rodríguez VA, Rojas MX, et al. Costos ambulatorios y hospitalarios de la falla cardiaca en dos hospitales de Bogotá. Acta Médica Colomb. 2013;38:208–212.

- Enciso A Evaluación económica de los dispositivos médicos utilizados en el tratamiento de diabetes en Colombia. 2016.

- Perlaza JG, Regino EAG, Lozano AT, et al. Costos de las Fracturas en mujeres con Osteoporosis en Colombia. Acta Médica Colomb. 2014;39. 46–56.

- Currie CJ, Morgan CL, Poole CD, et al. Multivariate models of health-related utility and the fear of hypoglycaemia in people with diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(8):1523–1534.

- Beaudet A, Clegg J, Thuresson PO, et al. Review of utility values for economic modeling in type 2 diabetes. Value Health. 2014;17(4):462–470.

- Clarke P, Gray A, Holman R. Estimating utility values for health States of type 2 diabetic patients using the EQ-5D (UKPDS 62). Med Decis Mak. 2002;22(4):340–349.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Guía de práctica clínica para el diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento de los pacientes mayores de 15 años con diabetes mellitus tipo 1. 2016 [Internet]. 2016 [ cited 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: http://gpc.minsalud.gov.co/