ABSTRACT

Objective

To evaluate work productivity of adult Latin American patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treated with tofacitinib and biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) measured by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) in RA questionnaire at 0- and 6-month follow-up.

Methods

This non-interventional study was performed in Colombia and Peru. Evaluated the effects of tofacitinib and bDMARDs in patients with RA after failure of conventional DMARDs. The WPAI-RA questionnaire was administered at baseline and at the 6-month (±1 month) follow-up. The results are expressed as least squares means (LSMs), and standard errors (SEs).

Results

One hundred patients treated with tofacitinib and 70 patients treated with bDMARDs were recruited. Twenty-eight percent of patients from the tofacitinib group and 40.0% from the bDMARDs group were working for pay at baseline. At month 6, the changes in absenteeism, presenteeism, and work impairment due to health were −18.3% (SE 7.7), −34.8% (SE 5.9), and −11.0% (SE 16.5), respectively, in the tofacitinib group and −19.4% (SE 8.0), −34.8% (SE 6.2), and −15.9% (SE 15.0), for the bDMARD group.

Conclusion

For patients who reported working, there were improvements in presenteeism, absenteeism, and work impairment due to health in both groups.

Trial registration

NCT03073109

1. Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an chronic systemic autoimmune disorder characterized by synovial membrane swelling, and it causes joint swelling, stiffness, and pain, which lead to cartilage and bone tissue progressive erosion and destruction at the affected joints [Citation1–4]. The treatment goals are to relieve disease signs and symptoms, control disease activity, improve physical function and patient quality of life, and inhibit structural damage progression during the disease course [Citation5–7].

A considerable proportion of RA patients suffer moderate or severe disability within a few years after disease onset and have to make a number of adjustments in their daily life and leave the workforce; thus, this disease imposes an economic burden, not only because of the direct costs associated with treatment but also due to the indirect costs resulting from the illness, including loss of work productivity [Citation8,Citation9].

The productivity of individual workers is directly affected by illnesses, and these effects are usually classified as either absenteeism or presenteeism. Absenteeism is defined as productivity loss due to health-related absence from work and includes sick days, personal time off, and time taken as short/long-term sick leave, whereas presenteeism refers to reduced performance or productivity while at work [Citation10]. It has been observed that the ability of RA patients from Latin American countries to perform their usual activities and their productivity are affected by the disease [Citation11,Citation12]. A correlation between RA disease activity and working impairment has also been reported [Citation13].

The goal of RA treatment is not only reducing the signs and symptoms of disease and inhibiting the progression of structural damage but also to decrease disease activity and improve quality of life, allowing patients to continue to work and thereby decreasing the socioeconomic burden of the disease [Citation14]. In the United States, it was reported that in employed patients with moderate-to-severe RA, etanercept led to significant reductions in overall work and activity impairment after 6 months of treatment [Citation15]. Similar findings were reported for RA patients in Japan treated with adalimumab for 48 weeks [Citation16].

However, at present, there was not identified evidence to evaluate the work productivity of patients treated with tofacitinib and those treated with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) in real-life conditions, particularly in Latin America; there is no evidence of work productivity. In this study, we aimed to assess the work productivity of adult Latin American RA patients treated with tofacitinib and bDMARDs, as measured by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) in RA questionnaire, at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up after failure to respond to conventional DMARDs (cDMARDs) in real-life conditions.

2. Methods

This noninterventional study (NIS) prospectively collected real‐world data regarding work productivity through the WPAI-RA as developed and validated patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for tofacitinib- and bDMARD-treated patients diagnosed with moderate-to-severe RA with inadequate response to cDMARDs. The study was approved by the independent ethics committee of each center.

Patients from Colombia and Peru were recruited between April 2017 and February 2019. Convenience consecutive sampling was conducted for the tofacitinib arm, and randomized sampling considering the different bDMARDs treatments available in the country was conducted for the bDMARDs arm. All eligible patients were adults that were 18 years and older, had an inadequate response to the continuous use of methotrexate or a combination of cDMARDs for at least 12 weeks before the study, did not previously use bDMARDs, were prescribed tofacitinib or bDMARDs in the last 3 weeks, and were treated according to clinical practice.

Once the informed consent was filled and signed, each patient was asked to complete the WPAI-RA questionnaire at baseline and at the 6-month (± 1 month) follow-up. The questionnaire consisted of six questions assessing the ability to work and perform regular activities; this PRO measured four domains: absenteeism, presenteeism, daily activity impairment, and overall work impairment (absenteeism plus presenteeism) attributable to the specific health problem, i.e. RA [Citation15,Citation17]. The validated Spanish version of the WPAI-RA was used (Spanish-Colombia v2.0) [Citation18].

The WPAI-RA outcomes are expressed as impairment percentages, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity [Citation19]; the questionnaire contained the following six questions with a recall period of the past week: Q1 = employment status; Q2 = hours missed due to health problems; Q3 = hours missed due to other reasons; Q4 = hours actually worked; Q5 = degree that health affected productivity while working; and Q6 = degree that health affected regular activities. Q1 was a yes/no question, Q2-Q4 asked for the number of hours (count data) and Q5-Q6 used a global rating scale, i.e. 0–10 (0 = no effect of health problems, 10 = health problems) [Citation20].

Four outcome scores were derived from the WPAI [Citation15,Citation19,Citation20]: (1) absenteeism (work time missed), defined as the percentage of time absent from work due to health in the last week, was calculated by the formula Q2/(Q2 + Q4) × 100%; (2) presenteeism (impairment at work), expressed as a percentage score representing the impairment due to health reasons while working, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity, was calculated by the formula (Q5/10) ×100%; (3) percent overall work impairment due to health (work productivity loss) was calculated by the formula Q2/(Q2 + Q4) + [(1 − Q2/(Q2+ Q4)) × (Q5/10)] ×100%; and (4) percent activity impairment due to health (activity loss) was calculated by the formula Q6/10 × 100%. Analysis of absenteeism was only performed for subjects who provided responses to the questions regarding hours missed and hours worked; analysis of presenteeism was only performed for subjects who provided a response to the question regarding productivity while working. For the analysis of overall work productivity, scores were only calculated for subjects who provided responses to the questions regarding hours missed, hours worked and productivity while working [Citation21]. The estimation of lost days per year due to absenteeism was derived from the number of hours lost in the last week projected to annual hours under the hypothetical scenario of 8 hours per day, 40 hours per week and 50 workweeks in the year. For presenteeism, the number of lost days was estimated by multiplying the number of annual worked hours by the percentage of impairment.

The quality of life, disease activity, and functional status were measured by the EuroQol Five-Dimensional questionnaire (EQ5D), Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3), Disease Activity Score including a 28-joint count (DAS28), and Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI).

Descriptive statistics were produced for all variables. These included estimates of the mean, standard deviation (SD), 95% confidence intervals of the mean, median, interquartile ranges, and frequency distributions for continuous-scale variables and frequency distributions for categorical-scale variables. Bivariate analysis, Student t test or ANOVA will be used for the comparison of quantitative variables with normal distribution, nonparametric Wilcoxon test for the comparison of quantitative variables that do not follow normal distribution.

The access limitation was defined as any barrier caused by administrative issues with the Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) or supplier reported by the patient; time to supply (TtS) as the number of days required for the delivery of treatment from the time of prescription; time with previous treatment as treatment used before of studies treatments measured in number of months, and access mechanism make a reference to type of health insurance.

All other demographic and clinical data were collected from patients’ medical records. Absenteeism, presenteeism, loss productivity, and activity were analyzed by directly estimating the difference in means using least square means (LSM) between patients treated studied treatment and periods. The results are expressed as unadjusted and adjusted LSMs; standard deviations (SDs) and standard errors (SEs) are reported as variability measures. Adjustment was made considering clinical, demographic covariables, and access barriers (i.e. age, previous use of methotrexate, access limitation, access mechanism, among others), which were demonstrated to be unbalanced between the studied groups. Other variables were not considered because they were not significantly different between groups. The adjusted LSMs for change from baseline at month 6 for each outcome score derived of WPAI were estimated using multivariable linear regression (Tables S3-S6 were reported the results of multivariable analysis for each treatment). The comparison between visits for each studied groups used paired t-test for unadjusted analysis and mixed effects regression analysis for adjusted results only including patients that reported WPAI questionnaire for both visits.

Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) was conducted to manage the missing baseline data using the package MICE in R software (version 4.0.5). It was conducted with five imputations using the predictive mean matching using only the baseline variables as predictors. In Table S7 in the supplementary material, the variables with missing data were described. Patients who did not report outcomes for both visits were not imputed using a complete case analysis.

3. Results

One hundred patients treated with tofacitinib and 70 patients treated with bDMARDs were recruited from 10 sites in Colombia and 3 from Peru. The mean ± SD age was 53.5 ± 13.8 years, and the mean ± SD disease duration was 6.3 ± 7.0 years. The majority of the population was female: 85% of patients in the tofacitinib group and 93% of patients in the bDMARDs group were female. Quality of life, disease activity and functional status were similar for both groups. Ninety patients from the tofacitinib group and 68 from the bDMARDs group reported data at both visits (). The characteristics of employee and non-employee population are described in Tables S1 and S2 of supplementary material.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics

Of the total enrolled patients, 158 patients (92.9%), 90 in the tofacitinib group and 68 in the bDMARDs group completed the 6-month follow-up, while 12 discontinued therapy; the most common reason for discontinuation was loss to follow-up (n = 9), followed by other reasons (n = 2) and adverse events (n = 1).

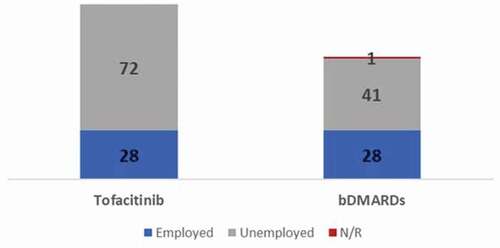

Of the total patients, 28.0% from the tofacitinib group (n = 28) and 40.0% from the bDMARDs group (n = 28) were working for pay at baseline (); the change from baseline at month 6 was estimated only for patients who reported data at both visits, 22 patients in the tofacitinib group and 22 patients in the bDMARDs group for absenteeism and 23 patients in the tofacitinib group and 21 patients in the bDMARDs group for both presenteeism and productivity loss. The change in activity impaired was calculated for patients with data reported at both visits regardless of working status (91 patients in the tofacitinib group and 68 in the bDMARDs group). Six patients treated with biologics and five treated with tofactinib did not report WPAI outcomes at 6-month visit. The clinical, demographic, and access variables of these patients were described in Table S8 of the supplementary material.

The employee patients were 49.1 ± 11.6 years old, and patients who were not employees were 55.6 ± 14.3 years old. The disease duration was similar between employee (7.12 ± 8.18) and nonemployee patients (5.91 ± 6.39). Likewise, the activity of disease, quality of life and functional status were similar for the PROs used to measure them. There were no differences in the baseline characteristics of employee patients and nonemployee patients ().

Table 2. WPAI outcomes: Change from baseline at month 6 according to work status

Overall, the mean hours of work lost per week because of RA was 23.2 at baseline, with absenteeism and presenteeism of 33.9% ± 36.9 and 57.8% ± 31.6, respectively, and a work impairment score of 63.9% ± 33.4. According to estimates of hours of work considering 40 hours per week and 50 weeks per year, RA patients lost 84.65 (12.45) days per year due to absenteeism and 144.44 (10.75) additional days per year due to presenteeism. After treatment with bDMARDs or tofacitinib for 6 months, these indicators improved significantly, with the mean hours of work lost per week being 4.28 hours and the absenteeism, presenteeism, and work impairment scores being decreased to 9.79% ± 25.2, 25.4% ± 24.8, and 28.2% ± 27.7, respectively, at month 6. This improvement in absenteeism and presenteeism represented a 60.3 (9.39) and 81.0 (9.15) workdays gained respectively produced by the studied therapies. The impact of lost days per year by studied group was reported in .

Table 4. Lost days per year due to absenteeism and presenteeism by studied groups

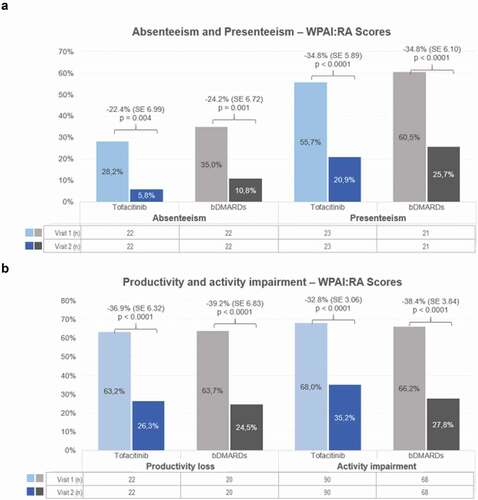

There were no differences in changes in unadjusted absenteeism, presenteeism, work impairment, and activity impairment scores from baseline between the tofacitinib and bDMARDs groups. After adjustment by covariables such as access limitation, previous use of methotrexate and complementary access mechanism by multivariable analysis, the same results were observed ().

Table 3. WPAI outcomes: Change from baseline at month 6 for each group

Unadjusted and adjusted WPAI-RA scores were significantly reduced from baseline to the 6-month follow-up for patients treated with tofacitinib and bDMARDs ( and 2B). The LSM of adjusted WPAI-RA score for tofacitinib-treated patients at baseline and at month 6 were 36.9% and 4.5% (p = 0.0038) for absenteeism, 55.6% and 20.8.1% (p < 0.0001) for presenteeism, 63.2% and 26.3% (p < 0.0001) for productivity loss, 75.7% and 42.9%, respectively (p < 0.0001) for activity loss, with a mean of 17.8 (45.9) hours of work lost per week because of RA; similarly, for bDMARDs-treated patients, absenteeism at baseline and month 6 was 37.5% and 13.3% (p = 0.001), presenteeism was 60.5% and 25.7% (p < 0.0001), productivity loss was 66.3% and 27.1% (p < 0.0001), activity loss 66.2% and 27.8%, respectively (p < 0.0001), with a mean of 11.3 (16.2) hours of work lost per week because of RA.

4. Discussion

The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of RA in Latin America was demonstrated in previous publications [Citation22]; however, its impact on work productivity and activity impairment has not been studied in this region. This is the first study evaluating work productivity and activity impairment in Colombia and Peru as well as comparing the changes resulting from tofacitinib and bDMARDs treatment in routine clinical care.

Although several questionnaires aimed at measuring productivity are available, it has been shown with the WPAI-RA questionnaire that a 7-day recall can accurately measure how the disease affects work productivity [Citation23]; therefore, this scale was used in this study. The findings suggest an improvement in presenteeism, absenteeism, and work impairment due to health in both groups (the tofacitinib and bDMARDs group) and reflect the impact of the disease on patients’ work.

The absenteeism and presenteeism scores reported by RA patients at baseline in this study were higher than those reported in other studies conducted in Latin American countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. According to this study, the mean scores of absenteeism and presenteeism were 9% and 29.7%, respectively. In particular, Colombian RA patients reported an absenteeism of 7.5% and a presenteeism of 40.5%, which are higher than the scores of participants in other countries [Citation24]. In this study, the patients reported lower quality of life and higher activity of disease, which explains the difference in work productivity scores between the two studies.

The improvements in these variables were manifested as a substantial reduction in absenteeism and presenteeism of 19.4% and 34.8%, respectively, which were higher than those of participants in Latin American countries according to other studies on etanercept and adalimumab [Citation15,Citation16]. Few publications have shown in a comparative manner the validity of the WPAI-RA questionnaire; in an observational study in the United States, it was reported that RA patients treated with etanercept for 6 months showed significant decreases in overall work impairment (41.9% at baseline versus 25.2% at 6 months; p < 0.0001), absenteeism (8.4% versus 2.3%; p = 0.0001), presenteeism (38.9% versus 24.3%; p < 0.0001), and activity impairment (55.7% versus 30.9%; p < 0.0001) and a 76.4% reduction in work hours lost weekly due to RA (3.2 versus 0.8; p = 0.0001) [Citation15]. Another observational study conducted in Japanese patients showed reductions in absenteeism (33.3% vs 14.7%), presenteeism (41.1% vs 23.8%) and work impairment (42.3% vs 24.9%) from baseline to 6 months [Citation16]. These results are similar to the findings of this observational study, in which there was a difference in both groups for outcomes related to work productivity, as measured by the WPAI-RA questionnaire. Those previous studies, however, reported lower disease activity than that indicated by the mean DAS28 score reported in this study.

A multicenter study in four countries from the Latin America region reported improvements in presenteeism (p = 0.020) and impairment of regular daily activities (p = 0.017) between the first and 1-year follow-up visits that could be associated with medication coverage/insurance and consultations in the last 3 months [Citation11]; another study carried out in Mexico revealed that a median of 20% of RA patients presented presenteeism at work (p25-p75: 0–50), while 26.9% presented loss of total work productivity (p25-p75: 0–56.2) [Citation13]; however, the results were described for all RA patients regardless of treatment and disease activity.

An improvement in work productivity suggests better functioning and less pain and fatigue; therefore, it has been correlated with a decrease in disease activity and functional status in RA patients, as measured by the HAQ and DAS28 [Citation16,Citation25–26]. Although they were not the objectives of this study, improvements in presenteeism, absenteeism, and impairment work at baseline and 6 months were also manifested by substantial reductions in DAS28, HAQ-DI, and RAPID3 scores.

The strengths of this study include the design, a prospective, real-life analysis capable of reflecting the variability of populations in clinical practice through access to medical records for a sufficient sample size for obtaining meaningful information on work productivity and activity impairment in Peru and Colombia. Additionally, this study used the WPAI-RA questionnaire, which is a scale that has been validated in RA patients and is easily completed by them [Citation2026Citation26.

Regarding to measure of work productivity, it is relevant to highlight the following considerations. First, the questionnaire evaluated the productivity insights only the previous 7 days to perform the survey (0 and 6 months), but it did not measure the behavior of productivity during all study period. Second, the time of stopped workdays was not precisely measured given that there are periods required to resume the work activities and also the level of productivity could be change. Third, the questionnaire does not collect information related to job characteristics and education, which are related to the level of impact in the work. Fourth, the questionnaire asks about loss productivity caused by health and not RA specifically.

The limitations of the current analysis should be considered. A lower percentage of patients working for pay was observed; however, this was an expected result because the prevalence of RA increases with age; in fact, the prevalence and incidence increase with age and peak at approximately age 70 [Citation27]. The small sample size is another limitation and it is also important to point out that this is not a representative study of the entire population of RA in Peru and Colombia, but all the sites at which the study enrolled patients are considered reference centers for the management of RA. Also, considering that the inclusion criteria were not limited to employed population and that this disease impact old people, the sample size was affected increasing the variability of the measures. Further publications should focus on the broader management of RA across countries. The interpretation of the results and conclusions of the study should take into consideration all the limitations listed, the characteristics of the population, the size of the sample, and consider other limitations inherent to real-world studies.

5. Conclusion

Most RA patients were not working for pay in this study. For those who reported working for pay, the studied drugs significantly improved productivity at work, as measured by changes in presenteeism, absenteeism, and work impairment and the reductions in the number of hours lost due to RA and activity impairment.

Declaration of interest

JM Reyes, MV Gutierrez, D Ponce de Leon, T Lukic, and L Amador are employees of Pfizer. D Del Castillo has received speaker fees from Lilly, Janssen, Bristol, Pfizer, Roche, Boehringer, Amgen, Pharmalab. J Izquierdo have received speakers fees from Roche, Pfizer, Amgen, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Pharmelab, and Biopas. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation was performed by J Reyes, M Gutierrez, L Amador, D Ponce de Leon, and T Lukic. The data collection was conducted by the different site participants. The analysis was executed by J Reyes and M Gutierrez, and reviewed by all the authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J Reyes and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol and that informed consent has been obtained from the subjects were approved by the Independent Ethics Committee at each center.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Research Centers for participating in this research: Centro Integral de Reumatología del Caribe Circaribe, SERVIMED, Centro de Investigaciones en Reumatología y Especialidades Médicas SAS, Reumalab, Fundación Valle de Lili, Clínica Jockey Salud, Clínica San Judas Tadeo, Clínicos IPS, Centro Medico CEEN, Fundación Instituto de Reumatología Fernando Chalem, Clínica de Occidente, Artmedica, and IDEARG and all the investigators who contributed their knowledge, expertise, and the integrity of the work as a whole. Likewise, we would like to thank all patients who took part in this research.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, et al. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955-2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1576–1582.

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15–25.

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(9):2569–2581.

- Prete M, Racanelli V, Digiglio L, et al. Extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis: an update. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;11(2):123–131.

- Smolen J, Ledenwé R, Breedveld F. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:964–975.

- Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:625–639.

- Ruffing V, Bingham C, Clifton O. Rheumatoid arthritis: treatment. Rheumatoid Arthritis; 2016 [accessed 2021 Aug 18]. https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/arthritis-info/rheumatoid-arthritis/ra-treatment/

- Lundkvist J, Kastäng F, Kobelt G. The burden of rheumatoid arthritis and access to treatment: health burden and costs. Eur J Heal Econ. 2008;8:49–60.

- Escorpizo RBC, Bombardier C, Boonen A, et al. Worker productivity outcome measures in arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1372–1380.

- Filipovic I, Walker D, Forster F, et al. Quantifying the economic burden of productivity loss in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2011;50:1083–1090.

- Xavier RM, Zerbini CAF, Pollak DF, et al. Burden of rheumatoid arthritis on patients’ work productivity and quality of life. Adv Rheumatol (London, England). 2019;59:47.

- da Rocha Castelar Pinheiro G, Khandker RK, Sato R, et al. Impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality of life, work productivity and resource utilisation: an observational, cross-sectional study in Brazil. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31:334–340.

- Salazar-Mejía CE, Galarza-Delgado DÁ, Colunga-Pedraza IJ, et al. Relationship between work productivity and clinical characteristics in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Reumatol Clin. 2019;15:327–332.

- Strand V, Khanna D. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis and treatment on patients’ lives. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:S32–40.

- Hone D, Cheng A, Watson C, et al. Impact of etanercept on work and activity impairment in employed moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis patients in the United States. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:1564–1572.

- Takeuchi T, Nakajima R, Komatsu S, et al. Impact of adalimumab on work productivity and activity impairment in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: large-scale, prospective, single-cohort ANOUVEAU study. Adv Ther. 2017;34:686–702.

- Almoallim H, Kamil A. Rheumatoid arthritis: should we shift the focus from “treat to target” to “treat to work?” Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:285–287.

- Associates R. WPAI translations: (rheumatoid arthritis) v2.0. 2016 Mar 21. http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_Translations-2.html

- Braakman-Jansen LMA, Taal E, Kuper IH, et al. Productivity loss due to absenteeism and presenteeism by different instruments in patients with RA and subjects without RA. Rheumatology. 2012;51:354–361.

- Tang K, Beaton DE, Boonen A, et al. Measures of work disability and productivity: rheumatoid arthritis specific work productivity survey (WPS-RA), workplace activity limitations scale (WALS), work instability scale for rheumatoid arthritis (RA-WIS), work limitations questionnaire (WLQ), an. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(1):S337–49.

- Associates R. WPAI Coding. 2016 Mar 21. http://www.reillyassociates.net/wpai_coding.html

- Radominski SC, Cardiel MH, Citera G, et al. Tofacitinib, un inhibidor oral de la quinasa Janus, para el tratamiento de artritis reumatoide en pacientes de Latinoamérica: eficacia y seguridad de estudios fase 3 y de extensión a largo plazo. Reumatol Clin. 2017;13:201–209

- Leggett S, van der Zee-neuen A, Boonen A, et al. Content validity of global measures for at-work productivity in patients with rheumatic diseases: an international qualitative study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1364–1373.

- Xavier RM, Zerbini CAF, Pollak DF, et al. Burden of rheumatoid arthritis on patients’ work productivity and quality of life. Adv Rheumatol. 2019;59:47

- Almoallim H, Janoudi N, Alokaily F, et al. Achieving comprehensive remission or low disease activity in rheumatoid patients and its impact on workability – Saudi rheumatoid arthritis registry. Open Access Rheumatol Res Rev. 2019; 11: 89–95.

- Symmons D, Mathers C, Pfleger B. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis in the year 2000; 2006 [accessed 2021 Aug 20]. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/bod_rheumatoidarthritis.pdf

- Zhang W, Bansback N, Boonen A, et al. Validity of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire - general health version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R177.