ABSTRACT

Introduction

Economic evaluations typically focus solely on patient-specific costs with economic spillovers to informal caregivers less frequently evaluated. This may systematically underestimate the burden resulting from disease.

Areas covered

Cost-of-illness (COI) analyses that identified costs borne to caregiver(s) were identified using PubMed and Embase. We extracted study characteristics, clinical condition, costs, and cost methods. To compare caregiver costs reported across studies, estimated a single ‘annual caregiver cost’ amount in 2021 USD.

Expert opinion

A total of 51 studies met our search criteria for inclusion with estimates ranging from $30 – $86,543. The majority (63%, 32/51) of studies estimated caregiver time costs with fewer studies reporting productivity or other types of costs. Caregiver costs were frequently reported descriptively (69%, 35/51), with fewer studies reporting more rigorous methods of estimating costs. Only 27% (14/51) of studies included used an incremental analysis approach for caregiver costs. In a subgroup analysis of dementia-focused studies (n = 16), we found the average annual cost of caregiving time for patients with dementia was $30,562, ranging from $4,914 to $86,543. We identified a wide range in annual caregiver cost estimates, even when limiting by condition and cost type.

1. Introduction

Recent efforts to systematically engage patients in cost-effectiveness analyses or value assessment frameworks have identified caregiver impact as a meaningful element of value [Citation1,Citation2]. Guidelines and best practices for cost-effectiveness and value assessment emphasize the importance of clearly specifying the perspective of the analysis for the specific decision the assessment seeks to inform [Citation3–5]. Analysis perspectives may vary to inform the decision for a single patient, a specific health plan, a government-sponsored health insurance for an entire country, or a broad perspective reflecting costs to all of society [Citation6]. Additionally, the decision context for cost-effectiveness studies is typically structured around a disease or specific treatment which focuses all elements of the analysis on patient-specific costs with economic spillovers to informal caregivers less frequently evaluated [Citation7–9].

A recent review of 7,605 cost-effectiveness studies from 1974 to 2018 found that a payer perspective analysis was utilized in 74% (5,617/7,605) of included studies with only 18% (1,387/7,605) taking a societal approach [Citation6]. In cases where a societal perspective analysis attempts to assess caregiver costs, the focus is typically on time or productivity losses incurred by the caregiver. However, research on caregiver burden suggests the true impact extends well beyond these domains throughout the patient journey across the continuum of care [Citation10,Citation11].

In the United States (US), the need for consideration of caregiving costs has been elevated following infrastructure policy proposed by the Biden Administration aimed at expanding access to home- and community-based services [Citation11,Citation12]. Currently in the US, elderly and people living with disabilities may qualify for home- and community-based services to support individuals receiving care at home rather than being admitted to institutionalized care (e.g. nursing home) [Citation13]. These services may include health services or human services. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services defines health services as items that meet medical needs such as home health care, durable medical equipment, case management, caregiver training, and hospice care, while human services support daily living (e.g. senior centers, personal care, transportation and access, home repairs, chore services, and legal services) [Citation14]. Any societal perspective analysis conducted as recommended by the Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine (Second Panel) [Citation5] should encompass all the costs associated with informal caregiving. Unfortunately, data gaps related to the full economic impact or uncertainty around the causal relationship between caregiving and incremental costs will still create significant challenges for any research team [Citation11,Citation15].

1.1. Cost-of-illness

Cost-of-illness (COI) studies are used to understand the financial burden of disease by addressing the total costs of a disease, or its incremental costs [Citation16,Citation17]. These studies focus on the impact of the disease at the individual and societal level, but the usefulness of COI studies have been subject to controversy. Some argue that COI studies yield insufficient results that can be used by policy makers to inform their decisions to allocate resources when compared to cost-effectiveness and cost-utility studies [Citation18]. COI studies have also been criticized for the inconsistency in methodology, reliability, potential risk of bias, and lack of transparency on how results are reported [Citation18–20]. However, COI analysis have been useful to underscore specific health problems and to inform the organization of healthcare services, they highlight the need for research that focuses on prevention, they also aid with the evaluation of policy options [Citation19].

1.2. Measuring the cost of caregiving

A variety of methods have been deployed in COI studies that include caregiver costs. First, the type of caregiver cost (e.g. healthcare costs, out-of-pocket expenditures, time costs, lost productivity) identified frequently varies across studies. Patients may require different levels of care across diseases or within the same disease based on the disease progression. Patients with more extensive caregiving needs may necessitate relocation, home renovations to support a wheelchair, or vehicle modifications [Citation10]. Once the type of cost has been identified, researchers have used a variety of methods for the same cost category. For example, the measurement of care time costs has been assessed a variety of ways with different methods of valuation. A researcher may estimate the time cost by directly measuring time spent caregiving through recall or diary methods or by indirectly estimating its costs by assessing its impact on displacing other time uses [Citation21]. Once the amount of time has been estimated, assigning a value to that time can vary from replacement cost to estimating potential market earnings [Citation21,Citation22].

In this review, we identify relevant COI studies based on their inclusion of caregiver costs, synthesize results specific to caregiver costs, and assess the evidence of caregiver costs. We did not limit our search to a specific disease to compare within and across clinical conditions. Given the expected heterogeneity in methods and patient populations, caregiver costs estimates were compared qualitatively with exploratory quantitative evaluation where cost types and patient populations were similar.

2. Materials and methods

For this systematic review, we used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations for organization and reporting [Citation23].

2.1. Search strategy

A systematic search to identify COI analyses that specifically identified costs borne to patients caregiver(s) was performed. Two electronic databases (PubMed and Embase) were searched from 1984 to 2021. The following search strategies were applied after consultation with a research librarian:

PubMed: (‘Caregivers’[Mesh] OR ‘Caregiver Burden’[Mesh] OR caregiv*[tiab] OR informal care[tiab]) AND (‘Costs and Cost Analysis’[Mesh] OR ‘Financial Stress’[Mesh] OR cost*[tiab]) AND (‘Models, Economic’[Mesh] OR economic model*[tiab])

Embase: (caregiver:ti,ab,kw OR ‘caregiver burden’/exp OR ‘caregiver support’/exp OR ‘informal care’/exp OR caregiver*:ti,ab,kw) AND (‘economic evaluation’/exp OR cost*:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cost analysis’:ti,ab,kw) AND model:ti,ab,kw

2.2. Eligibility criteria and study selection

Titles and abstracts of all articles were imported to Covidence® to facilitate de-duplication and abstract screening [Citation24]. For abstract review, two authors (TJM, VDF) independently screened each article for relevance to caregiving and reporting of costs specific to caregivers. Agreement for inclusion/exclusion was set at 80% a prior and both reviewers met after 100, 500, and 1,000 abstracts to determine the review whether the screening process was reaching an unacceptable level of agreement. After all abstracts were reviewed, all disagreements were discussed until full consensus researched. Following abstract screening, full-text review was completed by all four authors and final inclusion required group consensus.

2.3. Data extraction

We extracted citation information (authors, year, and journal), country, patient clinical condition, study type, analysis type, costs reported, time horizon for caregiver costs reported, description of cost methods, and study funding source. Study type was categorized broadly by interventional (e.g. randomized controlled trial, other clinical intervention study), observational (e.g. cohort, cross-section, case-control, case series), and modeling methods (e.g. Markov model, decision analytical model, other simulation methods). Analysis type was categorized in multiple ways where we identified whether the analysis used descriptive statistical methods only, regression, or matching and whether the caregiver costs were estimated by comparing the costs for a sample of patient-caregiver dyads with the condition to dyads without the condition (e.g. incremental) [Citation16,Citation17]. We anticipated time and productivity costs to be frequently reported, so dichotomous (Yes/No) variables were created for inclusion of caregiver time costs, caregivers productivity costs, and other identified caregiver costs.

2.4. Evidence synthesis

Categorical variables extracted (country, clinical condition, study type, analysis type, inclusion of time costs, inclusion of productivity costs, inclusion of other costs) were summarized. To compare caregiver costs reported across studies, we needed to consider country, cost year, and time costs were observed to estimate a single ‘annual caregiver cost’ amount. Extracted costs were first inflated to present value (2021) using the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPIu) [Citation25,Citation26] and then converted to United States Dollars (USD) using current exchange rates sourced from OANDA [Citation27,Citation28].

2.5. Subgroup analysis

Given the anticipated methods and population differences, we did not specify a subgroup for further analyses a priori. A subgroup analysis for all COI studies for caregivers of patients with dementia was determined post-hoc based on higher proportion of studies identified. We included any underlying source of dementia in the subgroup analysis (e.g. Alzheimer disease and related dementia, vascular dementia, or dementia from unspecified causes). Available point estimate (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation or inter-quartile range) measures were used for comparison.

2.6. Risk of bias

Qualitatively, we described the potential sources of bias specific to the cost estimates articles reported specific for caregivers. The costing method categorization aided in the risk of bias assessment, as statistical methods (e.g. matching, regression, incremental) may reduce certain types of bias in the resulting cost estimate [Citation17]. Studies reporting costs for caregiving descriptively with little to no statistical adjustments for cost estimates, no reported method of incorporating price inflation, or biased data sources were considered at a higher risk of bias. Source of funding was discussed as a potential source of bias and was extracted for reader consideration.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of study characteristics

The search strategy identified a total of 1,883 records with a total of 1,809 abstracts remaining after duplicates were removed (). After abstract screening, a total of 167 records were reviewed resulting in 51 unique studies that met our criteria for extraction and synthesis () [Citation29–79]. We identified COI studies with caregiver cost estimates from several countries around the globe, with multiple studies in the United States (13/51), Spain (6/51), Australia (4/51), Ireland (4/51), Germany (2/51), South Korea (2/51), Thailand (2/51), and the United Kingdom (2/51). The majority (51%, 26/51) were funded by a government grant, health system, or non-profit entity, 31% (16/51) were funded by industry, and the remaining 18% (9/51) did not declare any funding.

Figure 1. Review flow diagram according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement.

Table 1. Included study characteristics, methods, and annual caregiver costs reported in 2021 USD by clinical condition.

3.2. Cost methods

Included studies predominantly (73%, 37/51) used observational methods (e.g. case-control, cohort, cross-sectional) to estimate costs, 25% (13/51) used simulation/model methods, and one study was interventional [Citation45]. Caregiver costs were frequently (69%, 35/51) reported descriptively, with fewer studies reporting more rigorous methods of estimating costs such as regression (22%, 11/51) or matching with controls (10%, 5/51). Only 27% (14/51) of studies included used an incremental analysis approach for caregiver costs.

3.3. Types of caregiver costs

The majority (63%, 32/51) of studies attempted to estimate the cost of caregiver time. Caregiver time was frequently assessed using questionnaires to capture time spent and then valued using either an opportunity cost method or proxy method. Only 20 (39%) of studies explicitly reported productivity costs specific to caregivers. Beyond the costs associated with time or productivity losses, studies identified other costs borne by caregivers related to food purchases [Citation32,Citation47–49,Citation58,Citation60], transportation [Citation32,Citation48,Citation50,Citation58,Citation60], sanitary supplies [Citation58], lodging [Citation60], general out-of-pocket costs [Citation60], and home repair or cleaning [Citation48].

Low end estimates for caregiver time costs (<$1,000) were found in a variety of diseases including diabetes [Citation53], stroke [Citation71], heart failure [Citation55], and pemphigus (a rare, autoimmune blistering disease) [Citation68]. Two of these low end estimates were based on a Thai population [Citation53,Citation71] and one was based in Hungary [Citation68], all three with lower wage estimates for replacement compared to higher wage countries (e.g. US, Canada, and Germany). Joo et al. estimated the economic value of informal caregiving for caregivers of heart failure patients in the US with a replacement cost approach using a median health aide worker wage ($10/hour in 2010) to estimate an incremental annual caregiving time cost of just $927 [Citation55].

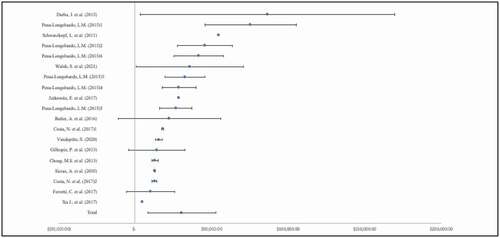

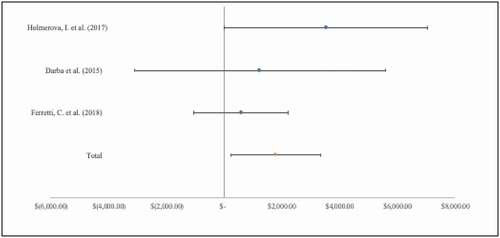

3.4. Subgroup analysis: caregiver costs in dementia

Of the included COI studies, we identified 16 peer-reviewed papers specifically focused on dementia and included caregiver costs. Within these, 9 studies [Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation42,Citation46,Citation48,Citation49,Citation51] provided cost estimates for caregiver time with 2 studies [Citation36,Citation51] reporting multiple estimates using different methods (). The average annual cost of caregiving, in terms of caregiver time, for individuals with dementia was $30,562 (SD: $ 21,598), ranging from $4,914 to $86,543. Similarly, 2 studies [Citation37,Citation46] were identified that reported caregiver productivity costs for caregivers of persons with dementia. The mean cost, in terms of lost productivity (), for caregivers of persons with dementia was $1,779 (SD: $1,542).

3.5. Risk of bias considerations

While no quantitative assessment within or across included COI studies was performed, we did qualitatively assess articles for potential sources of bias or areas that may limit the interpretation of the analysis. The methodological differences across studies were significant in caregiver cost types included in a broader ‘indirect cost’ or ‘informal care cost’ definition frequently reported as these labels may include time, productivity, or other costs. The costing methods for time frequently use an opportunity cost method or proxy method and the associated sources of time value (e.g. lost wages, value of leisure time, replacement costs) also varied. Additionally, whether caregiver costs identified were reported completely unadjusted or adjusted through a regression or matching process limits the potential comparison across studies or ability to attribute the caregiver costs to the patient’s clinical condition. There was also little consistency in time horizon consideration when reporting results. Studies varied from weekly caregiver costs to multi-year caregiver costs, requiring extrapolation steps for any comparisons across studies. Finally, whether costs were reported as an incremental cost against a non-caregiver comparator differed substantially, limiting the usefulness of comparisons between incremental cost studies and non-incremental cost studies.

4. Discussion

We performed a comprehensive review of COI studies, published in peer-reviewed journals, that reported costs specific to caregivers for patients across a variety of clinical conditions. By extracting reported costs, categorized by cost type, and converting to a single present-day currency, we were able to qualitatively compare across studies. Even when limiting our assessment by clinical condition (dementia) and by cost type (time and productivity), we see a wide range in annual caregiver cost estimates. This may reflect the significant heterogeneity of patient experiences within a single clinical condition, the variety of research methods, differences between health system structures, differences in values of time, or a combination of these.

High end estimates for annual caregiver time costs (>$50,000) were found in dementia [Citation37,Citation45] and cancer [Citation78]. Darbà and Kaskens assessed productivity losses using national hourly wage estimate at €12 and a replacement cost method for informal care time costs using an hourly wage for a healthcare assistant at €16 in a group of 343 Alzheimer's disease patients and caregivers [Citation37]. Schwarzkopf et al. used interviews with main caregivers at baseline, 12-months, and 24-months to assess time all informal caregivers spent on activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, and supervision in 247 mild dementia and 135 moderate dementia patient and caregiver dyads. Similar to Darbà and Kaskens [Citation37], Schwarzkopf et al. applied a replacement cost approach but applied differential wage estimates (€28/hour and €16) [Citation45]. Yu et al. identified different components of caregiver time to represent time lost from employment, leisure, and household work and valued each component differently by using the Human Capital Approach for productivity losses using market rates and replacement costs using an ‘average wage of a homemaker’ for leisure and household work time [Citation78]. Darbà and Kaskens [Citation37] and Yu et al. [Citation78] both reported non-incremental costs descriptively ($87,948 and $66,619/year respectively), while Schwarzkopf et al. [Citation45] adjusted for age, gender, and cluster-effects with a generalized linear mixed model ($54,692/year).

We identified studies that specifically reported productivity costs (absenteeism or presenteeism) without aggregating into a broader time cost or under an informal cost description with other cost types. Zhou et al. [Citation56] and Wan et al. [Citation77] both described ‘productivity loss’ when assessing absenteeism (time off work) but not presenteeism (reduced productivity at worth due to health problems). Sorensen et al. described the value of ‘lost work productivity’ but subsequently described a replacement cost approach common for caregiver time costs with no assessment of absenteeism or presenteeism [Citation76].

This review was limited by narrow inclusion criteria requiring articles to report a monetary value for caregiver costs. We determined this requirement would support across-study comparison with less manipulation (e.g. research team applying a valuation method). Considering there were still challenges in comparing across studies, we suggest potential evidence synthesis by identifying studies in a single clinical condition and including any cost or burden study where the time variable was collected (with or without monetary valuation). Using reported caregiving time estimates (e.g. number of hours, days, weeks), a standard valuation method or multiple valuation methods may improve comparability across studies. Our narrow study type (COI) criteria also limited our ability to capture all caregiver cost types. We felt other qualitative research methods and expert panels have identified a wider range of caregiver costs frequently experienced and that our limited focus would be more valuable to researchers interested in economic evaluation methods. Additionally, we extracted and reported the country where the cost estimates were made and adjusted the value for comparison, but we did not make additional adjustments for other cultural differences, levels of income, or health system structures. Finally, are data extraction and synthesis approach to categorize time and productivity costs separately may have been limited in balancing what authors reported in their methods versus reviewing the text and applying a single definition across all studies. We wanted to report what the authors reported with as little re-phrasing as possible, but this only highlights the challenges we have in the field with definitions around informal care terms. This further supports our recommendation for standardized language if consensus in the field can be reached.

5. Conclusion

We performed a comprehensive review of COI studies that reported costs specific to caregivers for patients across multiple conditions. We identified a wide range in annual caregiver cost estimates, even when limiting by condition and cost type. This may reflect the significant heterogeneity of patient experiences within a single clinical condition, the variety of research methods, differences between health system structures, differences in values of time, or a combination of these. This review may provide a useful starting point for identifying a base case caregiver cost estimate with potential ranges for sensitivity analyses in future economic evaluations.

6. Expert opinion

Approximately 74% published cost-effectiveness studies fail to evaluate costs beyond the health care sector perspective [Citation6], despite the recommendations of previous expert task force panels who have consistently recommended the consideration of costs beyond direct healthcare costs [Citation3,Citation5,Citation80]. This may be due to a lack of data or funding to support the collection of such data. For a cost-effectiveness analysis or value assessment framework, this review may provide a useful starting point for identifying a base case caregiver cost estimate with potential ranges for sensitivity analyses. Simply omitting caregiver costs in an economic model due to data limitations may be inappropriate for diseases where substantial caregiving costs have been identified (e.g. dementia, stroke, cancer, and pediatric illnesses).

The inconsistency in which COI researchers define costs borne by caregivers and the frequency in which terms such as ‘caregiver costs,’ ‘informal care,’ ‘indirect costs,’ and ‘non-health costs’ are interchanged creates significant challenges for study comparison or practical use in research results. In many cases where caregiver time was estimated and valued using an opportunity cost method, ‘lost wages’ may have been used essentially estimating caregiver productivity costs similar to absenteeism costs. For researchers explicitly estimating caregiver productivity cost estimates, presenteeism was frequently omitted. Krol and Brouwer offer guidance on appropriately estimating productivity costs for economic evaluations [Citation81]. Finally, the infrequency of ‘other cost’ types such as relocation expenses, home renovations to support a wheelchair, vehicle modifications, or other ancillary services to support daily living may suggest that the full economic burden for caregivers continues to be systematically underestimated. Having clear definitions around caregiver cost types and consistent application of these definitions would help with dissemination and implementation of study results. We recommend the Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) work to establish a consensus definition and encourage leading health economics journal editors to consider adopting uniform definitions regarding these costs and work with the broader research community to use consistent definitions.

The role of caregiving in the context of patient care and health services delivery may have substantial variation across populations for a variety of reasons. These may include cultural differences (e.g. expectations of adult children to serve as caregivers for elderly parents), availability of government support, employer policies (e.g. flexible work hours, leave time), or family dynamics (e.g. family size and proximity). Health systems that aim to provide better patient experiences, improved population health, and cost-effective care may need to consider family and other social network dynamics influencing patients. These system considerations may be at the individual-, family-, community-, regional-, or national-level depending on the health system and local jurisdiction. As current studies prevailingly come from high-income countries, more research in low and middle-income countries would be interesting in the future. Additionally, these caregiving relationships and supports may provide additional insights for observed health disparities or heterogeneity of outcomes in populations.

Finally, we identified very few studies that attempted to assess the costs of spillover effects from caregiving. Since the landmark Caregiver Health Effects Study estimated a greater risk of mortality in caregivers compared to non-caregiver controls, conflicting evidence has clouded the ‘caregiving → negative health effects’ causal relationship [Citation82,Citation83]. In our review, we identified one study where spouses of persons with dementia were compared to matched controls and assessed health problems, utilization, and costs [Citation43]. While the study estimated greater risk of anxiety disorders, falls, rheumatologic diseases, and diabetes, they found no statistically significant differences in costs [Citation43]. While it may be plausible to consider the increased burden of caregiving may be a risk factor for negative health effects, this relationship needs further study. The current body of COI evidence overwhelming focuses on assessing costs specific to time spent caregiving, rather than considering caregiving as an exposure and other health costs as an outcome.

Article highlights

A total of 51 studies met our search criteria for inclusion with estimates ranging from $30 – $86,543.

In a subgroup analysis (n = 16), we found the average annual cost of caregiving time for patients with dementia was $30,562, ranging from $4,914 to $86,543

Caregiver costs were frequently reported descriptively with fewer studies reporting more rigorous methods of estimating costs.

Caregiver costs typically focus on the value of time loss or productivity loss.

Caregiver costs types for patients with more extensive caregiving needs such as relocation, home renovations, or vehicle modifications were not commonly identified.

Declaration of interest

T Mattingly II reports grant support from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and PhRMA Foundation and consulting fees from the Arnold Foundation and PhRMA unrelated to this work. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Manuscript concept and design: All; Drafting of manuscript: T Mattingly II; Critical reviews: All; all authors approved and agree for the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Emily Gorman, MLIS, AHIP, for her search strategy consultation.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mattingly IITJ, Slejko JF, Perfetto EM, et al. What matters most for treatment decisions in hepatitis C: effectiveness, costs, and altruism. Patient. 2019;12:631–638.

- dosReis S, Butler B, Caicedo J, et al. Stakeholder-engaged derivation of patient-informed value elements. Patient. 2020;13:611–621.

- Garrison LP, Pauly MV, Willke RJ, et al. An overview of value, perspective, and decision context—A health economics approach: an ISPOR special task force report [2]. Value Heal. 2018;21:124–130.

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS)–explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR health economic evaluations publication guidelines task force. Value Heal. 2013;16:231–250.

- Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for Conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;316:1093–1103.

- Kim DD, Silver MC, Kunst N, et al. Perspective and costing in cost-effectiveness analysis, 1974–2018.Pharmacoeconomics.2020;38:1135–1145.

- Lin PJ, D’Cruz B, Leech AA, et al. Family and caregiver spillover effects in cost-utility analyses of Alzheimer’s disease interventions. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37:597–608

- Lavelle TA, D’Cruz BN, Mohit B, et al. Family spillover effects in pediatric cost-utility analyses. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17:163–174**Authors. DOI:10.1007/s40258-018-0436-0.

- Krol M, Papenburg J, van Exel J. Does including informal care in economic evaluations matter? A systematic review of inclusion and impact of informal care in cost-effectiveness studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:123–135.

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2016.

- Mattingly TJ, Wolff JL. Caregiver economics: a framework for estimating the value of the American jobs plan for a caring infrastructure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:2370–3.

- The White House. Fact sheet: the American jobs plan [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Apr 2]. Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/03/31/fact-sheet-the-american-jobs-plan/

- Beauregard LK, Miller EA. Why do states pursue medicaid home care opportunities ? Explaining state adoption of the patient protection and affordable care act’s home and community-based services initiatives Russell Sage found. J Soc Sci. 2020;6:154–178.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Home & community based services authorities. 2021

- Hoefman RJ, van Exel J, Brouwer WBF. The monetary value of informal care: obtaining pure time valuations using a discrete choice experiment. Pharmacoecon. 2019;37:531–540.

- Akobundu E, Ju J, Blatt L, et al. Cost-of-illness studies: a review of current methods. Pharmacoecon. 2006;24:869–890.

- Onukwugha E, McRae J, Kravetz A, et al. Cost-of-illness studies: an updated review of current methods. Pharmacoecon. 2015;34:43–58

- Kymes S. “Can we declare victory and move on?” The case against funding burden-of-disease studies. Pharmacoecon. 2014;32:1153–1155.

- Larg A, Moss JR. Cost-of-illness studies: a guide to critical evaluation. Pharmacoecon. 2011;29:653–671.

- Mattingly IITJ, Love BL, Khokhar B. Real world cost-of-illness evidence in hepatitis C virus: a systematic review. Pharmacoecon. 2020;38:927–939.

- Grosse SD, Pike J, Soelaeman R, et al. Quantifying family spillover effects in economic evaluations: measurement and valuation of informal care time. Pharmacoecon. 2019;37:461–473.

- Coe NB, Skira MM, Larson EB. A comprehensive measure of the costs of caring for a parent: differences according to functional status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:2003–2008.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

- Covidence systematic review software. [Internet] Melbourne Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; Available from: www.covidence.org

- Berndt ER, Cutler DM, Frank RG, et al. Price indexes for medical care goods and services: an overview of measurement issues. In: Cutler DM, Berndt ER, editors. Medical Care Output Product. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2007. p. 141–200.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Archived Consumer Price Index Supplemental Files [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables/supplemental-files/home.htm

- Turner HC, Lauer JA, Tran BX, et al. Adjusting for inflation and currency changes within health economic studies. Value Heal. 2019;22:1026–1032.

- OANDA Corporation. Currency Converter [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www1.oanda.com/currency/converter/

- Oliva-Moreno J, Peña-Longobardo LM, García-Mochón L, et al. The economic value of time of informal care and its determinants (The cuidarse study). PLoS One. 2019;14:1–16.

- Schofield D, Zeppel MJB, Tanton R, et al. Informal caring for back pain: overlooked costs of back pain and projections to 2030. Pain. 2020;161:1012–1018.

- Wolff N, Perlick DA, Kaczynski R, et al. Modeling costs and burden of informal caregiving for persons with bipolar disorder. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2006;9:99–110.

- Chan ATC, Jacobs P, Yeo W, et al. The cost of palliative care for hepatocellular carcinoma in Hong Kong. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:947–953.

- Hayman JA, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, et al. Estimating the cost of informal caregiving for elderly patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3219–3225.

- Ortega-Ortega M, Montero-Granados R, Jiménez-Aguilera JDD. Differences in the economic valuation and determining factors of informal care over time: the case of blood cancer. Gac Sanit. 2018;32:411.

- Sorensen SV, Goh JW, Pan F, et al. Incidence-based cost-of-illness model for metastatic breast cancer in the United States. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28:12–21.

- Wan Y, Gao X, Mehta S, et al. Indirect costs associated with metastatic breast cancer. J Med Econ. 2013;16:1169–1178.

- Yu M, Guerriere DN, Coyte PC. Societal costs of home and hospital end-of-life care for palliative care patients in Ontario, Canada. Heal Soc Care Community. 2015;23:605–618. DOI:10.1111/hsc.12170.

- Dunbar SB, Khavjou OA, Bakas T, et al. Projected costs of informal caregiving for cardiovascular disease: 2015 to 2035: a policy statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2018;137:e558–e577.

- Schofield D, Shrestha RN, Zeppel MJB, et al. Economic costs of informal care for people with chronic diseases in the community: lost income, extra welfare payments, and reduced taxes in Australia in 2015–2030. Heal Soc Care Community. 2019;27:493–501.

- Turchetti G, Bellelli S, Amato M, et al. The social cost of chronic kidney disease in Italy. Eur J Heal Econ. 2017;18:847–858.

- Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J, Hidalgo-Vega Á, et al. Economic valuation and determinants of informal care to disabled people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) utilization, expenditure, economics and financing systems. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:1–8.

- Butler A, Gallagher D, Gillespie P, et al. Frailty: a costly phenomenon in caring for elders with cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:161–168.

- Chong MS, Tan WS, Chan M, et al. Cost of informal care for community-dwelling mild-moderate dementia patients in a developed Southeast Asian country. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2013;25:1475–1483.

- Costa N, Wübker A, De Mauléon A, et al. Costs of care of agitation associated with dementia in 8 European countries: results from the right time place care study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:95.e1–95.e10.

- Darbà J, Kaskens L. Relationship between patient dependence and direct medical-, social-, indirect-, and informal-care costs in Spain. Clin Outcomes Res. 2015;7:387–395. DOI:10.2147/CEOR.S81045.

- Ferretti C, Sarti FM, Nitrini R, et al. An assessment of direct and indirect costs of dementia in Brazil. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193209.

- Gillespie P, O’Shea E, Cullinan J, et al. The effects of dependence and function on costs of care for AlzheimerAlzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in Ireland. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(3):256–264.

- Holmerová I, Hort J, Rusina R, et al. Costs of dementia in the Czech Republic. Eur J Heal Econ. 2017;18(8):979–986.

- Jutkowitz E, Kane RL, Gaugler JE, et al. Societal and family lifetime cost of dementia: implications for policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2169–2175.

- Kolanowski AM, Fick D, Waller JL, et al. Spouses of persons with dementia: their healthcare problems, utilization, and costs. Res Nurs Heal. 2004;27:296–306.

- Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J. Economic valuation and determinants of informal care to people with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Heal Econ. 2015;16:507–515.

- Schwarzkopf L, Menn P, Kunz S, et al. Costs of care for dementia patients in community setting: an analysis for mild and moderate disease stage. Value Heal. 2011;14:827–835.

- Sicras A, Rejas J, Arco S, et al. Prevalence, resource utilization and costs of vascular dementia compared to Alzheimer’s dementia in a population setting. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19:305–315.

- Suh GH, Knapp M, Kang CJ. The economic costs of dementia in Korea, 2002. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:722–728.

- Vandepitte S, Van Wilder L, Putman K, et al. Factors associated with costs of care in community-dwelling persons with dementia from a third party payer and societal perspective: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:1–13.

- Walsh S, Pertl M, Gillespie P, et al. Factors influencing the cost of care and admission to long-term care for people with dementia in Ireland. Aging Ment Heal. 2021;25:512–520.

- Xu J, Wang J, Wimo A, et al. The economic burden of dementia in China, 1990-2030: implications for health policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:18–26.

- Bermudez-Tamayo C, Besançon S, Johri M, et al. Direct and indirect costs of diabetes mellitus in Mali: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–15.

- Chatterjee S, Riewpaiboon A, Piyauthakit P, et al. Cost of informal care for diabetic patients in Thailand. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;5:109–115.

- Cho H, Oh SH, Lee H, et al. The incremental economic burden of heart failure: a population-based investigation from South Korea. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–13.

- Joo H, Fang J, Losby JL, et al. Cost of informal caregiving for patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2015;169:142–148.e2.

- Zhou ZY, Koerper MA, Johnson KA, et al. Burden of illness: direct and indirect costs among persons with hemophilia A in the United States. J Med Econ. 2015;18:457–465.

- Andersson A, Levin LÅ, Emtinger BG. The economic burden of informal care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2002;18:46–54.

- Tomita S, Hoshino E, Kamiya K, et al. Direct and indirect costs of home healthcare in Japan: a cross-sectional study. Heal Soc Care Community. 2020;28:1109–1117.

- Kahn SA, Lin CW, Ozbay B, et al. Indirect costs and family burden of pediatric Crohn’s disease in the United States. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:2089–2096.

- Shannon CN, Simon TD, Reed GT, et al. The economic impact of ventriculoperitoneal shunt failure: clinical article. J Neurosurg Pediatr PED. 2011;8:593–599.

- Schofield D, Zeppel MJB, Tanton R, et al. Intellectual disability and autism: socioeconomic impacts of informal caring, projected to 2030. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215:654–660.

- Diminic S, Lee YY, Hielscher E, et al. Quantifying the size of the informal care sector for Australian adults with mental illness: caring hours and replacement cost. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56:387–400.

- Carney P, O’Boyle D, Larkin A, et al. Societal costs of multiple sclerosis in Ireland. J Med Econ. 2018;21:425–437.

- Schreiber-Katz O, Klug C, Thiele S, et al. Comparative cost of illness analysis and assessment of health care burden of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies in Germany. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:210.

- Rafferty ER, Schurer JM, Arndt MB, et al. Pediatric cryptosporidiosis: an evaluation of health care and societal costs in Peru, Bangladesh and Kenya. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–16.

- Burke RM, Smith ER, Dahl RM, et al. The economic burden of pediatric gastroenteritis to Bolivian families: a cross-sectional study of correlates of catastrophic cost and overall cost burden. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:642. DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-14-642.

- Brodszky V, Tamási B, Hajdu K, et al. Disease burden of patients with pemphigus from a societal perspective. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2021;21:77–86.

- Tilford JM, Grosse SD, Goodman AC, et al. Labor market productivity costs for caregivers of children with spina bifida: a population-based analysis. Med Decis Mak. 2009;29:23–32.

- Brown DL, Boden-Albala B, Langa KM, et al. Projected costs of ischemic stroke in the United States. Neurology. 2006;67:1390–1395.

- Riewpaiboon A, Riewpaiboon W, Ponsoongnern K, et al. Economic valuation of informal care in Asia: a case study of care for disabled stroke survivors in Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:648–653.

- Youman P, Wilson K, Harraf F, et al. The economic burden of stroke in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:43–50.

- Van Den Berg B, Brouwer W, Van Exel J, et al. Economic valuation of informal care: lessons from the application of the opportunity costs and proxy good methods. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:835–845.

- Thompson HJ, Weir S, Rivara FP, et al. Utilization and costs of health care after geriatric traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1864–1871.

- Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Russell LB, et al. Recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analyses. JAMA. 1996;276:1339–1341.

- Krol M, Brouwer W. How to estimate productivity costs in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:335–344.

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:2215–2219.

- Roth DL, Fredman L, Haley WE. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: a reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist. 2015;55:309–319.