ABSTRACT

Introduction

This study assessed the societal costs of multiple sclerosis (MS) in Lebanon, categorized by disease severity.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional, prevalence-based, bottom-up study using a face-to-face questionnaire. Patients were stratified by disease severity using the expanded disability status scale (EDSS); EDSS scores of 0–3, 4–6.5, and 7–9 indicating respectively mild, moderate, and severe MS. All direct medical, nonmedical, and indirect costs related to reduced productivity were accounted for regardless of who bore them. Costs, collected from various sources, were presented in international US dollars (US$) using the purchasing power parity (PPP) conversion rate.

Results

We included 210 Lebanese patients (mean age: 43.3 years; 65.7% females). The total annual costs per patient were PPP US$ 33,117 for 2021, 12.4 times higher than the nominal GDP per capita. Direct costs represented 52% (US$ 17,185), direct nonmedical costs 8% (US$ 2,722), and indirect costs 40% (US$ 13, 211) of the mean annual costs. The total annual costs per patient increased with disease severity and were PPP US$ 29,979, PPP US$ 36,125, PPP US$ 39,136 for mild, moderate, and severe MS, respectively.

Conclusion

This study reveals the huge economic burden of MS on the Lebanese healthcare system and society.

1. Introduction

A considerable number of cost-of-illness (COI) studies performed on multiple sclerosis (MS) reported substantial costs [Citation1–3]. For example, the estimated lifetime cost per MS patient in the United States was US dollars (US$) US$ 4.1 million in 2010 [Citation4]. While the economic burden of MS has been extensively assessed in high-income countries (HICs) [Citation5,Citation6], information on the economic burden in low and middle‐income countries (LMICs), such as Lebanon, remains scarce [Citation7].

Since October 2019, Lebanon has been through a series of worsening and complex crises. These are due to regional instability, political turbulence, financial and economic meltdown, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the aftermath of the explosion of Beirut’s port in 2020 that devastated the country’s capital [Citation8]. These crises exacerbated the malfunctioning of a health system suffering for decades from fragmented governance of health coverage associated with a diverse financing system, a weak public health sector [Citation9], where 82% percent of hospitals are privately owned, and while tertiary care has predominance over preventive and primary care [Citation10]. Lebanon is still facing issues related to universal health coverage despite efforts. The country is characterized by six types of governmental payers in addition to private insurance, each having their own percentage of coverage and tariff [Citation8,Citation9,Citation11].

Before the financial crisis, out-of-pocket expenses accounted for 33% of total health expenditures [Citation9]. This percentage increased in recent years as the proportion of coverage by governmental third-party payers remained unchanged despite the increase in the market prices of health resources [Citation8]. The multidimensional crises severely impacted access to, and consumption of healthcare services and medications. Before the crises, most first- and second-line disease modifying therapies (DMTs) of MS were available in Lebanon, and fully subsidized and reimbursed for Lebanese patients by governmental third-party payers [Citation11].

In Lebanon, the number of people with MS (PwMS) was estimated in 2018 at 62.91 cases per 100,000 persons, with a female-to-male ratio of 2:1 [Citation11]. Lebanon is following the International Classification of Disease (ICD-9 code 340 or ICD-10 G35 code) [Citation11] and the clinical management guidelines of MS [Citation12]. Valuing the economic burden of MS and exploring cost drivers are necessary to inform public health planning and budgeting decisions in general, and specifically in the context of these prevailing crises. To date, no studies have addressed the economic burden of MS on Lebanese society. This study aims to assess the societal cost of MS per patient in Lebanon, categorized by disease severity, and explore the main cost drivers at different severity levels.

2. Materials and methods

The detailed study approach and methods used in this article were presented in Dahham et al. [Citation13]. We provide here a summary of these methods.

2.1. Study design

This cross-sectional, prevalence-based, bottom-up, burden-of-illness study aggregated data from patients through a validated questionnaire. The study was executed in collaboration with the Nehme and Therese Tohme Multiple Sclerosis Center at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC), a leading hospital in Lebanon. Ethical approval (SBS-2019-0268) was obtained from the AUB Institutional Review Board [Citation13].

The study was conducted amid a triple disaster in Lebanon – the drastic economic and financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the consequences of the explosion of Beirut’s port [Citation8], in light of which our results were analyzed.

2.2. Data collection

Lebanese patients were invited to participate during their visit to the MS center if they were ≥18 years old and had been diagnosed, according to the 2017 McDonald criteria [Citation14], with Relapsing-Remitting MS, or Primary Progressive MS, or Secondary Progressive MS for >six months. Non-Lebanese patients were excluded. A purposive sampling was used to recruit patients, with the aim of enrolling enough subjects at each level of disease severity defined by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [Citation15]. A trained interviewer collected data through face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire. Data were collected during clinical visits from December 2020 to August 2021. Data collection was suspended during the government-imposed COVID-19 lockdown period. Confidentiality was guaranteed by anonymizing recruitment; each participant was assigned an ID number and provided informed consent [Citation13].

2.3. Cost perspective

The study adopted a societal perspective. Accordingly, all costs that burden society were accounted for whenever possible, irrespective of who incurs them, including out-of-pocket expenses. The COI followed a macro-costing approach, following three steps: identification, measurement, and valuation [Citation8,Citation13,Citation16].

Step I: Identification of Costs

Included costs were categorized [Citation1,Citation7,Citation17] as (1) direct medical costs: healthcare consumption such as hospitalization, consultations, medications, and medical tests; (2) direct non-medical costs: equipment, home and automobile modifications, professional home care (formal care), informal care provided by family and friends, and patients’ travel expenses to reach healthcare facilities; and (3) indirect costs related to reduced productivity [Citation13].

Step II: Measurement of costs

An MS Health Resource Use Questionnaire extensively used in various economic burden of MS studies [Citation2,Citation3,Citation17] was adapted to the Lebanese context [Citation13]. The questionnaire requested information on demographic characteristics and disease data including prevalent symptoms, information on relapses, severity of disability using patient self-assessed EDSS [Citation15], healthcare and service consumption, formal care, informal care, and workforce participation. The effect of MS on productivity during the past 7 days was collected using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (no problem) to 10 (severe problems) [Citation13]. The recall time periods were 3 months to ensure the best possible recall. Only the question related to investment in devices, equipment, and aids was collected over the last 12 months [Citation13].

Step III: Valuation of costs

The detailed approach for valuating costs during the Lebanese financial and economic crisis was detailed in Dahham et al., where data sources used were clearly referenced and validated with key informant interviews, and by clinical and economic experts [Citation8]. The costs of drugs were derived from the Lebanese National Drug List [Citation18]. Informal care was estimated using the proxy good method [Citation19] and productivity losses were based on the human capital approach [Citation20]. Short-term and long-term absenteeism costs were calculated only for employed patients of working age (18–64 years), and early retirement was calculated for unemployed patients of working age. The mean quantity/frequency of use of each service was multiplied by its respective mean unit cost to obtain the total costs. Missing data on the consumption of health resources (volume) were replaced by the mean value reported by patients. All costs except those related to DMTs were collected and calculated in Lebanese pounds (LBP). The cost of DMTs was calculated separately in US$, as these subsidized drugs are imported and paid for in EURO and US$, based on the average exchange rate of 1 US$ per 0.97 EURO for the year 2021. When calculating costs, data were annualized (costs per quarter multiplied by four) with the assumption that resource consumption is equal in any given quarter. The total annualized cost for all patients was divided by the number of included patients to estimate the mean annual cost.

Considering the soaring inflation and the gradual lifting of subsidies during data collection, we conducted a sensitivity analysis, in which we adopted two scenarios: Scenario 1 (minimum cost: before subsidies were lifted based on the average market price in the first six months of 2021), and Scenario 2 (maximum cost: after subsidies were lifted based on the average market price in the second six months of 2021). Market prices for healthcare and other resources in our 2021 COI inventory were collected from multiple sources to get reflective market prices of the different existing economic and social classes. Thus, we calculated two sets of data for all costs included in this study as plausible scenarios to quantify the variation in the value of used resources and evaluate these costs in light of the change in the currency purchasing power and the progression of the consumer price index (CPI) as consequent of the hyperinflation [Citation8]. Unit costs of both scenarios are available in the supplementary material.

Given the deterioration of the LBP, costs in LBP are not meaningful and do not serve as valid comparators [Citation8]. Thus, the costs of Scenario 2 were converted to purchasing power parity (PPP) US$ using the World Bank PPP exchange rate for the year 2021 (2,958.13) [Citation21] as this rate reflected the market prices’ progression in 2021 after subsidies were lifted. We then added the cost of DMTs in US$ to the costs of Scenario 2 in PPP US$ for 2021.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Patients were stratified according to disease severity using the EDSS, whereby scores of 0–3, 4–6.5, and 7–9 indicate mild, moderate, and severe MS, respectively. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 21. Patient characteristics, resources consumption, and costs were described as relative frequencies for categorical data and as means (standard deviation) for continuous data. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to determine whether the difference between severity levels is statistically significant (p < 0.05). 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) and partial eta squared (ɳ2; effect size) were also recorded.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the sample

A total of 210 patients were included (range = 20–79 years; mean (SD) 43.3 (12.9) years; females: 65.7%). Around two-thirds (66.2%) were married, 25.2% were main family providers, and 33.8% had a university degree.

Respectively, 55%, 32%, and 13% of the patients had mild, moderate, and severe MS, with a mean EDSS of 3.1 (2.7). Mean age of first symptoms was 31.2 (10.5) years, and mean age at disease onset was 33.4 (SD = 11.3) years. DMTs were used by 86.7% of the sample. Relapses in the preceding 3 months were reported by 9 patients (4.3%) and 4 patients were unsure if they experienced any relapses.

While 95.2% of participants were below the official retirement age, 42.4% were employed or self-employed, and 12.9% were unemployed due to MS, with unemployment increasing with disease severity. Short-term absence from work during the past 3 months was reported by 15.7% of working patients, and long-term absence by 2.2%. TheMS effect on productivity during the past 7 days was reported by all employed patients mean (SD):1.8 (2.6), increasing with severity levels ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients, disease information, and employment.

3.2. Resource utilization

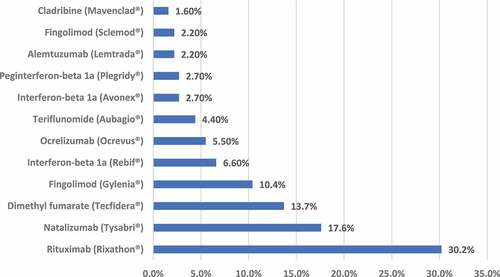

Hospitalization use during the preceding 3 months was low, whereas use of health consultations was high (93.3%, with 86.7% consulting a neurologist); mean of 1 visit per quarter (SD = 0.6). While DMTs were used by 86.7% of patients, only 3.8% received relapse treatments. Among users, Rituximab (Rixathon®), Natalizumab (Tysabri®), and Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®) were the DMTs most used, at 30.2%, 17.6%, and 13.7%, respectively (). Other prescription and non-prescription drugs were consumed by 99% of patients: predominantly vitamin D (96.7%), with consumption increasing across severity levels. Tests were used by 63.3% of the sample, predominantly blood tests (58.1%) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (36.2%); 19.5% invested in medical equipment and devices during the past 12 months – mainly walking aids and wheelchairs, with investments increasing with severity levels. A total of 19.5% of the sample received assistance in formal care and informal care. Informal care was used twice as much as formal care, and both types of care increased with greater disease severity. All patients used transportation (mean: 1.6 trips (SD = 1) for 3 months). Only 15% of the patients received financial aid; 81% of these were supported by the Friends of MS, an association supporting patients treated at the AUBMC MS center ().

Table 2. Resource utilization, health care and community services among all patients in the total sample and by EDSS level.

3.3. Costs

details total annual costs per patient for 2021, excluding costs of DMTs. The accounted costs ranged between LBP 26,804,242 for Scenario 1, and LBP 66,702,504 for Scenario 2. For both scenarios, the total mean annual costs per patient, excluding DMTs, increased with disease severity. All included sub-costs for both scenarios are detailed in the supplementary material.

Table 3. Total mean (SD) annual costs per patient in 2021 LBP for Scenarios 1 and 2 of the sensitivity analysis, excluding DMTs, by EDSS classification groups.

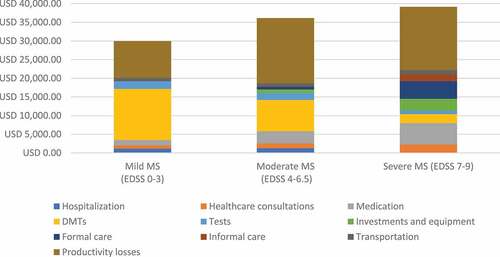

and () detail the total annual costs per patient converted to year 2021 PPP US$, including DMTs. The total annual costs per patient was PPP US$ 33,117, with total direct medical costs representing 52% (PPP US$ 17,185), total non-medical costs 8% (PPP US$ 2,722), and total indirect costs 40% (PPP US$ 13,211). Mean annual costs increased significantly across MS severity levels, being PPP US$ 29,979 (95%CI 27,403–32,555) in patients with mild MS, PPP US$ 36,125 (95%CI 32,857–39,394) in patients with moderate MS, and PPP US$ 39,136 (95%CI 33,477–44,796) in patients with severe MS (p < 0.001 for trend). The mean annual cost of DMTs was US $10,569, significantly decreasing with disease severity, from US$ 13,706 to US$ 2,394 in patients with mild and severe MS, respectively (p < 0.001). The total direct medical cost decreased when moving from mild (PPP US$ 19,203), to moderate (PPP US$ 16,036), to severe (PPP US$ 11,316) EDSS levels (p < 0.001 for trend). Finally, the mean total non-medical costs and total indirect costs increased significantly with disease severity (p < 0.001 for both trends).

Figure 2. Total mean annual costs per patient converted to year 2021 PPP US$ and presented by EDSS classification groups.

Table 4. Total mean annual costs per patient for scenario 2, including DMTs, converted to year 2021 PPP US$ and presented by EDSS classification groups.

DMTs were the main cost driver in mild EDSS, representing 45.7% of the total cost, while productivity losses were the main cost driver in moderate and severe EDSS (48.4% and 43.2% of the total costs, respectively).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first COI study on MS conducted in Lebanon from a societal perspective. Total annual costs per patient, including DMTs, were PPP US$ 33,117 for the year 2021, 3.1 times higher than the Lebanese gross domestic product (GDP) per capita PPP [Citation22] and 12.4 times higher than the nominal GDP per capita [Citation23]. Furthermore, in 2021 the mean annual costs per patient in LBP, excluding DMTs, for Scenario 1 (LBP 26,804,242) increased up to 2.5 times in Scenario 2 (LBP 66,702,504), after subsidies were lifted. This increase is consistent with the Lebanese hyperinflation seen in the CPI progression [Citation24] between the first and second six months of 2021, whereby both overall and health CPIs increased in the second half of the year (after subsidies were lifted) by 200% and 350%, respectively [Citation8]. Our estimated mean annual cost (PPP US$ 33,117) falls in the range of a recent systematic review revealing that total annual costs per MS patient in LMICs for 2019 ranged between US $6,463 and US $58,616 [Citation7].

For Scenario 1 and 2, respectively, the cost ratios for moderate versus mild MS were 1.71 and 1.70, and for severe versus mild MS 2.48 and 2.26, while these costs ratios were 1.21 and 1.31 for the costs presented in PPP US$. The difference in the margin between costs ratios for moderate versus mild, and severe versus mild MS can be explained by the inclusion of DMTs costs in their imported prices in US$, given that DMTs are a main cost driver of total direct medical costs for mild MS. Even though the usage of DMTs decreased with severity levels, their US$ costs still outweighed other direct medical costs such as hospitalization, consultations, and tests which were all priced in the devalued LBP. However, our costs results are consistent with previous studies on the COI of MS in HICs [Citation25,Citation26] and LMICs [Citation3,Citation7]. These studies also demonstrated that total costs increased with MS severity, consistent with increases in the total non-medical costs and total indirect costs, and that DMTs accounted for the majority of direct medical costs among patients with mild MS, and that pertaining cost decreased with disease severity, as available DMTs are less used in severe MS [Citation27]. Similar to other studies [Citation25,Citation26], our results confirm that DMTs are the main cost driver among patients with mild EDSS, and productivity losses are the main cost driver among moderate and severe EDSS groups.

Although, the characteristics of MS patients in our study are similar to those reported in a prevalence of MS study in Lebanon [Citation11], our sample may not be representative of MS patients in Lebanon. Thus, estimated costs cannot be extrapolated without weighting the actual prevalence by MS severity distribution in Lebanon.

Our results should be interpreted in light of the Lebanese-specific context and factors associated with the prevailing crises. The low use of hospitalization and inpatient services and the reduction of tests performed within the severe MS level (relative to mild and moderate MS) might follow the reduction of non-emergency operations and preventive health care due to fears of these highly vulnerable, often disabled patients contracting severe infections including COVID-19 [Citation28]. In addition, this low use of inpatient and outpatient services could be due to the decline of expenditures on both preventive and primary healthcare services as a consequence of the economic crisis [Citation29]. High consumption of prescription and non-prescription drugs relates to the high Lebanese trend toward using complementary and alternative medicine [Citation30], despite the devaluation of the LBP. MS relapses were reported by only 9 patients; this low rate is explained by the AUBMC MS center’s diligent patient follow-up and expertise in clinical management. The usage of informal care at twice the rate of formal care is expected due to lack of community services in Lebanon and the cultural dependence on help from family and friends; this was also found in another COI study in Lebanon [Citation31]. In addition, another consequence of the financial crisis was that most Lebanese could no longer afford to pay nurses in LBP or migrant domestic workers in foreign currency, thus aggravating the gap. Indirect costs were slightly lower for patients with severe MS (PPP US$ 16,922) compared with those with moderate MS (PPP US$ 17,478), as 15% of severe MS patients were above retirement age and therefore not included in the cost estimation. The early retirement cost of mild MS (PPP US$ 9,882) was more than 50% of these costs for moderate MS and severe MS, due to the high unemployment among adults resulting from the economic meltdown [Citation32]. We faced several additional challenges, as information on health unit costs is not publicly available in Lebanon, and the volatility of prices for health care and other resources during the financial and economic crisis aggravated this issue [Citation8]. Thus, the average market prices for health resources were obtained from multiple and various sources; the strengths and limitations of this approach are explained elsewhere [Citation13].

This study has several strengths. First, we estimated overall costs and by disease severity levels, the latter showing how cost drivers differ with the progression of MS. Studies on the burden of MS indicate that consumption of healthcare resources and associated costs increase with higher EDSS scores [Citation7,Citation17]. Second, although data were collected only from the AUBMC MS Center, this is the first specialized referral center in Lebanon, providing treatment to one-third of the Lebanese patients [Citation11]. Moreover, data collected on transportation confirmed that patients from all five Lebanese governorates are treated at this center. Third, we used the societal perspective, preferred by economists [Citation33], and we accounted for subsidized costs. Fourth, we used a bottom-up costing approach, considered suitable for chronic diseases [Citation34]. Fifth, we collected data using an interview-based questionnaire used extensively in MS research, predominantly using a 3-month recall period to minimize recall bias; this resulted in few missing responses [Citation13]. Sixth, we strived to valuate costs amid the financial and economic crisis by using recommended and validated methods, conducting a sensitivity analysis, adjusting costs for inflation [Citation35], and reporting costs in LBP and PPP US$ using the World Bank 2021 PPP rate [Citation36]. However, there are limitations. First, annualizing costs with the assumption that there were no quarterly variations in consumption of healthcare resources, especially in an unstable economic situation and after periods of COVID-19 lockdown, might create bias. Second, some costs such as the average national gross monthly wage and informal care costs in Scenario 2 were estimated in the absence of national data. Also, given the market turmoil, it was challenging to reflect black market prices. Third, although a few sub-costs such as other medications and fuel are minor cost drivers, these costs were estimated without considering their full subsidized values.

Under these difficult circumstances, where assumptions are infinite, calculating all costs twice, based on two six-month market price averages, and then in US$ PPP was thought to be the most realistic approach to reflecting the Lebanese context. Thus, our results provide a significant indication of the burden of MS, which might be slightly underestimated but is certainly not overestimated. Currently, some MS DMTs are not available due to the worsening economic crisis in Lebanon. As DMTs reduce relapse risk, preserve neurological function [Citation27], and postpone MS progression [Citation37], their absence may increase costs of relapses, direct non-medical costs, and productivity losses, thus aggravating the MS burden.

5. Conclusion

This study pioneers in assessing the costs of MS in Lebanon from a societal perspective and reveals the high economic burden of MS in Lebanon. Our results are in line with existing literature in terms of cost drivers, where costs increased with increasing disability, dominated by DMTs in mild MS and by productivity losses in moderate and severe disease. These results shall draw the public’s attention to the precise economic impact that MS poses on Lebanese society in light of the prevailing crises that further contributed to the scarcity of health resources. This paper presents data that could be used in researching the cost-effectiveness of DMTs for MS in Lebanon, previously unexplored. Moreover, in the absence of local health economic guidelines in LMICs [Citation38], we expect that our approach adopted in reporting the detailed valuation of costs and explaining the country-specific context will foster discussion on the importance of resilience and transparency of COI studies in Lebanon and LMICs.

Article highlights

Though the economic burden of multiple sclerosis (MS) has been extensively assessed in high-income countries (HICs), such information in low–and middle-income countries (LMICs), such as Lebanon, remains limited.

In this study we assessed the societal costs (including all direct medical, non-medical, and indirect costs) of MS in Lebanon, categorized by disease severity using the expanded disability status scale (EDSS); where EDSS scores of 0–3, 4–6.5, and 7–9 indicated mild, moderate, and severe MS, respectively.

This study reveals the huge economic burden of MS on the Lebanese healthcare system and society. We reported high total annual costs per patient; purchasing power parity (PPP) US dollars (US$) 33,117 for 2021, 12.4 times higher than the nominal GDP per capita.

The total annual costs per patient increased with disease severity and were PPP US$ 29,979, PPP US$ 36,125, PPP US$ 39,136 for mild, moderate, and severe MS, respectively.

Our results are in line with existing literature in terms of cost drivers, where costs increased with increasing disability, dominated by disease modifying therapies (DMTs) in mild MS and productivity losses in moderate and severe disease.

The high burden of MS shall draw the public’s attention to the precise economic impact that MS poses on Lebanese society in general, and specifically in light of the prevailing crises that further contributed to the scarcity of health resources.

Declaration of interests

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval (SBS-2019-0268) was obtained from the American University of Beirut Institutional Review Board.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the concept and design. Valuation of costs and statistical analysis were performed by J Dahham, M Hiligsmann, and R Rizk. Results were interpreted by J Dahham, M Hiligsmann, I Kremer, S Evers, and R Rizk. J Dahham drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree for the final version to be published and to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Informed consent

All patients provided written informed consent for the collection of clinical and health economic information.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (37.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Mrs. Lina Abdul Latif-Malaeb, Clinical Research Manager at the

American University of Beirut Medical Center, Nehme and Therese Tohme Multiple Sclerosis Center, for her support in collecting data from MS patients related to health resources consumption. A draft of the work/data was presented as an abstract at the 14th Lowlands Health Economic Study Group (LolaHESG) held in Maastricht, in May 2022.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2023.2184802

Additional information

Funding

References

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from five European countries. Mult Scler. 2012 Jun;18(2 Suppl):7–15.

- Calabrese P, Kobelt G, Berg J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for Switzerland. Mult Scler. 2017 Aug;23(2_suppl):192–203.

- Boyko A, Kobelt G, Berg J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for Russia. Mult Scler. 2017 Aug;23(2_suppl):155–165.

- Owens GM, Olvey EL, Skrepnek GH, et al. Perspectives for managed care organizations on the burden of multiple sclerosis and the cost-benefits of disease-modifying therapies. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013 Jan-Feb;19(1 Suppl A):S41–53.

- Ernstsson O, Gyllensten H, Alexanderson K, et al. Cost of illness of multiple sclerosis - a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159129.

- Paz-Zulueta M, Parás-Bravo P, Cantarero-Prieto D, et al. A literature review of cost-of-illness studies on the economic burden of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020 Aug;43:102162.

- Dahham J, Rizk R, Kremer I, et al. Economic burden of multiple sclerosis in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021 Jul;39(7):789–807.

- Dahham J, Kremer I, Hiligsmann M, et al., Valuation of costs in health economics during financial and economic crises: a case study from Lebanon. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2023. 21(1): 31–38.

- MoPH. 2022. Lebanon national health strategy-vision 2030. Beirut: Republic of Lebanon Ministry of Public Health. Lebanon National Health Strategy-Vision 2030 (moph.gov.lb):Accessed 2023 Feb 10.

- Khalife J, Rafeh N, Makouk J, et al. Hospital contracting reforms: the Lebanese ministry of public health experience. Health Syst Reform. 2017;3(1):34–41.

- Zeineddine M, Hajje AA, Hussein A, et al. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Lebanon: a rising prevalence in the Middle East. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021 Jul;52:102963.

- Yamout B, Alroughani R, Al-Jumah M, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis: the Middle East North Africa Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (MENACTRIMS). Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(7):1349–1361.

- Dahham J, Rizk R, Hiligsmann M, et al. The Economic and societal burden of multiple sclerosis on Lebanese society: a cost-of-illness and quality of life study protocol. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2021 Nov 26;22:1–8.

- Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Feb;17(2):162–173.

- Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983 Nov;33(11):1444–1452.

- Riewpaiboon A. Measurement of costs for health economic evaluation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014 May;97(Suppl 5):S17–26.

- Kobelt G, Thompson A, Berg J, et al., New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler. 2017. 23(8): 1123–1136.

- MoPH. Drugs public price list 2021: republic of Lebanon Ministry of Public Health. Available from: https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Drugs/index/3/4848/lebanon-national-drugs-database#/en/view/58026/drugs-public-price-list cited 2022 Jul 10

- Koopmanschap MA, van Exel JN, van den Berg B, et al. An overview of methods and applications to value informal care in economic evaluations of healthcare. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(4):269–280.

- Hodgson TA. Costs of illness in cost-effectiveness analysis. A review of the methodology. Pharmacoeconomics. 1994 Dec;6(6):536–552.

- WB. PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $) - Lebanon: the world bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP?locations=LB cited 2022 Aug 12

- WB (2022) GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) - Lebanon. The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?locations=LB. cited 12 August 2022

- WB (2022) GDP per capita (current US$) - Lebanon. The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=LB. cited 2022 Aug 12

- CAS (2022) Consumer Price Index CPI. Central Administration of Statistics. http://cas.gov.lb/index.php/economic-statistics-en. cited 2022 Aug 12

- Rasmussen PV, Kobelt G, Berg J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for Denmark. Mult Scler. 2017 Aug;23(2_suppl):53–64.

- Blahova Dusankova J, Kalincik T, Dolezal T, et al. Cost of multiple sclerosis in the Czech Republic: the COMS study. Mult Scler. 2012 May;18(5):662–668.

- Wingerchuk DM, Carter JL. Multiple sclerosis: current and emerging disease-modifying therapies and treatment strategies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):225–240.

- Bizri AR, Khachfe HH, Fares MY, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: an insult over injury for Lebanon. J Community Health. 2021 Jun;46(3):487–493.

- Devi S. Lebanon faces humanitarian emergency after blast. Lancet. 2020 Aug 15;396(10249):456.

- Naja F, Alameddine M, Itani L, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Lebanese adults: results from a national survey. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:682397.

- Rizk R, Hiligsmann M, Karavetian M, et al. A societal cost-of-illness study of hemodialysis in Lebanon. J Med Econ. 2016 Dec;19(12):1157–1166.

- Kharroubi S, Naja F, Diab-El-Harake M, et al. Food insecurity pre- and post the COVID-19 pandemic and economic crisis in Lebanon: prevalence and projections. Nutrients. 2021 Aug 27;13:9.

- Lavelle TA, D’Cruz BN, Mohit B, et al. Family spillover effects in pediatric cost-utility analyses. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019 Apr;17(2):163–174.

- Cortaredona S, Ventelou B. The extra cost of comorbidity: multiple illnesses and the economic burden of non-communicable diseases. BMC Med. 2017 Dec 8;15(1):216.

- Turner HC, Lauer JA, Tran BX, et al. Adjusting for inflation and currency changes within health economic studies. Value Health. 2019 Sep;22(9):1026–1032.

- J H, S G (2011) Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. cited 2022 Jun 14

- Goodin DS, Bates D. Treatment of early multiple sclerosis: the value of treatment initiation after a first clinical episode. Mult Scler. 2009 Oct;15(10):1175–1182.

- Daccache C, Rizk R, Dahham J, et al. Economic evaluation guidelines in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2021 Dec 21;38(1):e1.