ABSTRACT

Introduction

Likewise other medical interventions, economic evaluations of homeopathy contribute to the evidence base of therapeutic concepts and are needed for socioeconomic decision-making. A 2013 review was updated and extended to gain a current overview.

Methods

A systematic literature search of the terms ‘cost’ and ‘homeopathy’ from January 2012 to July 2022 was performed in electronic databases. Two independent reviewers checked records, extracted data, and assessed study quality using the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list.

Results

Six studies were added to 15 from the previous review. Synthesizing both health outcomes and costs showed homeopathic treatment being at least equally effective for less or similar costs than control in 14 of 21 studies. Three found improved outcomes at higher costs, two of which showed cost-effectiveness for homeopathy by incremental analysis. One found similar results and three similar outcomes at higher costs for homeopathy. CHEC values ranged between two and 16, with studies before 2009 having lower values (Mean ± SD: 6.7 ± 3.4) than newer studies (9.4 ± 4.3).

Conclusion

Although results of the CHEC assessment show a positive chronological development, the favorable cost-effectiveness of homeopathic treatments seen in a small number of high-quality studies is undercut by too many examples of methodologically poor research.

Plain Language Summary

To help make decisions about homeopathy in healthcare, it is important, as with other medical treatments, to look at whether this treatment is effective in relation to its costs; in other words, to see if it is cost-effective. The aim of the current work was to update the picture of scientific studies available on this topic until 2012. To this purpose, two different researchers screened electronic literature databases for studies between January 2012 and July 2022 which assessed both the costs and the effects of a homeopathic treatment. They did this according to strict rules to make sure that no important study was missed. They reviewed the search results, gathered information from the studies, and assessed the quality of the studies using a set of criteria. They detected six additional new studies to the 15 already known from the previous work. Overall, they found that in 14 out of 21 studies, homeopathic treatment was at least equally effective for less or similar costs. For the remaining seven studies, costs were equal or higher for homeopathy. Of these seven, two were shown to be advantageous for homeopathy: indeed, specific economic analyses demonstrated that the benefit of the homeopathic treatment compensated for the higher costs. For the remaining five studies, the higher or equal costs of homeopathic treatment were not compensated by a better effect. The quality of the studies varied, with older studies generally being of lower quality compared to newer ones. The authors concluded that although the quality of research on homeopathy’s cost-effectiveness has improved over time, and some high-quality studies show that it can be a cost-effective option, there are still many poorly conducted studies which make it difficult to offer a definitive statement. In other words, while there is some evidence that homeopathy can be effective in relation to its costs, there are still many studies that are not very reliable, which means that interested parties need to be cautious about drawing conclusions.

1. Introduction

In many countries the use of homeopathy is rather common in the general population. A systematic review of the 12-month prevalence of homeopathy use based on survey data from 11 countries (U.S.A., UK, Australia, Israel, Canada, Switzerland, Norway, Germany, South Korea, Japan, Singapore) demonstrated that each year a small but significant proportion (median 3.9%, range 0.7–9.8%) of the general population consults homeopaths or purchases over-the-counter (OTC) homeopathic medicines [Citation1]. Among 1,323 parents who visited the pediatric departments of two hospitals in Germany in 2015 and 2016, 40% stated that they were already using therapies of complementary and integrative medicine (CIM) for their children. Homeopathy was the most frequently mentioned CIM therapy with almost 60% of parents confirming its use, followed by osteopathy and phytotherapy. More than 80% of the participants supported the expansion of CIM in hospitals and stated that they would be willing to pay for these treatments if not covered by their health insurance [Citation2]. Similar patient preferences were reported in a forced-choice experiment [Citation3] in 263 subjects in Germany that investigated indirect health benefits in CIM and conventional medicine. Patients in the homeopathy and acupuncture subsets were less cost-sensitive and considered deductible fees to be less important than those in the general medicine group. The authors concluded that acupuncture and homeopathy patients may be more used to out-of-pocket payments.

An economic analysis of the data of the nation-wide EPI3 survey conducted in France in 2007 and 2008 [Citation4] showed that the social-security expenses for treatments by homeopathic general practitioners (GPs) were about 35% lower than for conventional GPs, while supplementary health insurance and out-of-pocket costs were slightly higher for treatments by homeopathic GPs due to higher consultation costs. The authors concluded that the management of patients by GPs certified in homeopathy may be less expensive from a global perspective and may be advantageous from the public health’s point of view. Similar observations were found in Switzerland, where a cross-sectional questionnaire-based investigation of mandatory health insurance claims data was conducted for 562 primary care physicians with and without a certificate for CIM, including homeopathy. From the perspective of the Swiss health system the analysis showed 15.4% lower costs for physicians certified in homeopathy compared to physicians applying conventional medicine [Citation5]. In a small-scale study performed in a real-world setting in UK, more than 90% of 84 evaluable patients treated with homeopathic preparations had lower pharmacy costs than they would have had using conventional medicinal products for the same conditions [Citation6].

An economic analysis of pharmacy-based self-care and self-medication with non-prescription (OTC) drugs was performed from the German societal perspective. It revealed net savings of about 21 billion euros p.a. of expenses for applicable medical services and products and a further 6 billion euros savings due to lowered sick leave-associated losses of productivity and working hours. Overall, each euro spent by consumers on self-medication according to this analysis translates into net savings of 17 euros in resources otherwise needed for the statutory health insurance sector and the national economy [Citation7]. In line with these findings, it is assumed that homeopathic treatment via OTC medications contributes to patient care and relieves the burden on the health care system by conserving scarce resources of health-care professionals as well as money. It may thus be beneficial from a health economic perspective.

Two analyses of data of German health insurance companies came to partly conflicting results. One of them found a reduction in morbidity as well as in the utilization of health insurance resources by patients who took homeopathy in almost all indications studied [Citation8]. Another data analysis compared the health care costs for patients subscribed to the German Integrated Care Contract ‘Homeopathy’ (ICCH) with the costs for those receiving standard care. Health claims data of 44,550 patients from a large statutory health insurance company were analyzed from both the societal perspective and from the statutory health insurance perspective, and both showed higher costs in the homeopathy group as compared to propensity score-matched controls over 18 months [Citation9], which also remained higher after 33 months [Citation10] despite a convergence tendency. While these studies [Citation9,Citation10] compared only costs but not treatment effects, information on cost-effectiveness was not provided.

Homeopathic treatment has been shown to have additional patient-relevant benefits. A recent review [Citation11] suggests that the prophylactic and therapeutic use of CIM, including homeopathic medicines, may be an important contribution to reducing the widespread overuse of antibiotics in a variety of conditions. In the EPI3 survey patients with upper respiratory tract infections who consulted a certified homeopathic GP were significantly less likely to use antibiotic, antipyretic, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs than those treated by a conventional GP even though their clinical outcomes were similar [Citation12]. In the same survey, patients with anxiety or depression consulting a certified homeopathic GP were significantly less likely to use psychotropic drugs than those treated by a conventional GP, whereas there was a tendency toward better outcomes in the homeopathy group [Citation13]. In a randomized trial that included patients with recurrent tonsillitis, study participants who received the homeopathic preparation SilAtro-5–90 in addition to conventional treatment were at a lower risk of subsequent tonsillitis episodes, exhibited a lower symptom burden, and were less likely to use antibiotics than those who received conventional therapy alone [Citation14].

The objective of health economic research is to provide a scientific rationale for the allocation of limited healthcare and economic resources to consistently assure high-quality care to patients. Health economic considerations based on costs and effectiveness can be applied to homeopathic treatments and to other forms of CIM in the same manner as they are applied to conventional therapies. In 2011, however, it was stated that for CIM ‘more clinical and health service research is needed which includes economic data to provide realistic cost estimates for future healthcare’ [Citation15]. Unfortunately, this conclusion still appears to hold today [Citation16].

Viksveen et al [Citation17] retrieved and assessed 15 economic evaluations of homeopathy in a comprehensive literature search about economic evaluations of homeopathy covering the period until April 2012. Eight found improvements in patients’ health with homeopathy together with cost savings. Five studies found that improvements in homeopathy patients were at least as good as in control group patients at similar costs. Two studies found improvements similar to conventional treatment at higher costs. Although the authors identified evidence of the costs and potential benefits of homeopathy, they concluded that the overall evidence for cost-effectiveness still seemed uncertain and was limited by the substantial heterogeneity of results and methodological issues.

1.1. Aims

The aim of this systematic review was to update the previous review [Citation17] and provide a current overview of the cost-effectiveness of homeopathy. Additionally, the quality of all economic evaluations published until July 2022 was assessed.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search

The literature search for the period starting in January 2012 was conducted in July 2022 and followed the methodology described previously [Citation17]. The literature databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases DARE, NHS EED, HTA, and Cochrane Library were searched for variations of the words ‘homeopathy’ and ‘cost,’ using the Boolean operator ‘AND’ and wildcard symbols as appropriate for each database. No filter for language was set. In addition, the major homeopathy journal Homeopathy was searched for the word ‘cost,’ and a manual search was performed of relevant literature known to the authors.

2.2. Selection of studies

All hits were screened by two authors independently. Each individual title was considered for relevance, and if in doubt, the abstract or full article was reviewed. Studies were included when they met three criteria: they were identified as a study in humans; they were published in a peer-reviewed journal; and they described full economic evaluations (i.e. analysis of homeopathic treatment in comparison to another health intervention in terms of both costs and outcomes with comparators including do nothing, placebo, conventional drug or other health intervention or before to after homeopathic treatment). Studies on animal, plant or in vitro investigations were excluded, as were studies assessing CIM treatment but not specifying results for homeopathy. Furthermore, studies were excluded as well if no data either on costs or clinical outcomes were reported; if there was only a single intervention without a comparator; or if only a congress abstract was available.

2.3. Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed to ensure a standardized, uniform process for the assessment of the literature. It accounted for the following different elements and steps required in economic evaluations [Citation18,Citation19]: study population characteristics, intervention and comparator, analysis technique and perspective, health outcome measures, scope of costs, currency and price year, time horizon and discount rates, main results as well as sensitivity analysis and results.

The number of participants analyzed was used to determine study population. Analysis techniques included cost-effectiveness analysis, which was defined as an economic evaluation that measures costs in a monetary unit and quantifies a single outcome in a physical or natural unit (e.g. number of successfully treated patients, number of life years gained, number of symptom days averted) as well as cost-utility analysis. The latter was defined as an economic evaluation that measures costs and outcomes by means of specific health-related quality of life measures such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). For price year, the year of manuscript submission or publication was assumed when no price year was specified, and sensitivity analyses were taken into consideration where information on cost and outcome or incremental cost-effectiveness/cost-utility ratio were reported.

Data extraction of one study [Citation20] was carried out as a pilot, and outcomes were discussed between all authors to reach consensus about completing the form. Afterwards all other studies were assessed independently by two authors. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer and, if there was still no consensus, a final assessment was obtained through discussion among the entire team of authors.

2.4. Quality assessment of included studies

The Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list was applied for quality assessment [Citation18] of each study by two authors independently. The CHEC list focuses on the methodological quality of economic evaluation aspects. It includes 19 criteria which are to be answered with ‘yes’ (i.e. sufficient attention is given to this aspect), ‘no’ (i.e. insufficient attention is given to this aspect), or ‘not applicable’.

2.5. Data analysis

A descriptive synthesis of the extracted data was performed by summarizing the characteristics and the results of the included studies in overview tables. To compare costs between studies, costs were updated to euros (€) values in 2022 using the CCEMG-EPPI-Centre Cost Converter online tool (https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/); purchasing power parities were based on data from the International Monetary Fund.

Based on a format suggested by Nixon et al [Citation21], a graphic depiction summarizing the correlation between observed costs and health outcome effects was created.

To investigate changes in the quality of health economic studies in homeopathy over time, linear regression analysis was performed with the CHEC score (number of positively answered items) as the dependent variable and publication year as a predictor.

3. Results

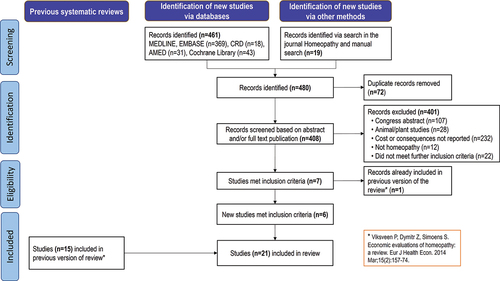

The literature search from January 2012 to July 2022 resulted in 408 records after removal of 72 duplicates (). After screening, six studies were newly identified which met the selection criteria [Citation20, Citation22–26]. Together with 15 studies already included in the previous systematic review [Citation27–41], 21 studies were available for analysis.

3.1. Analysis of included studies

3.1.1. Characteristics of studies

The characteristics of newly included studies are presented in . Updated and extended information on the studies covered by the previous review [Citation17] and reflecting our own work is shown in .

Table 1. Data extraction from newly identified studies.

Table 2. Data extraction of previously identified studies, updated and extended.

The studies were published between 1993 and 2021 with data from Germany (six national studies [Citation22, Citation25, Citation31, Citation33, Citation40, Citation41], two international studies [Citation20, Citation29]), the United Kingdom (four studies [Citation28,Citation32,Citation36,Citation38]), Italy (three studies [Citation23, Citation26, Citation30]), France (two studies [Citation34, Citation35]), Switzerland (two studies [Citation24, Citation39]), Belgium (one study [Citation37]), and the Netherlands (one study [Citation27]).

Primary health outcome measures were highly heterogeneous and included various symptom scores (e.g. SCORing Atopic Dermatitis [Citation25, Citation31] or Diabetic Neuropathy Symptom score [Citation30]), as well as self-rated or observer-rated clinical status (e.g. symptom severity [Citation24, Citation33, Citation37], Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile (MYMOP) [Citation36, Citation38]) or quality of life ratings (e.g. Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ) [Citation28], SF-12 [Citation22] or EQ-5D [Citation29]). Furthermore, the number or proportion of some clinical events of interest observed or avoided (recurrence of acute rhinopharyngitis [Citation34, Citation35], of acute throat infections [Citation20] or of respiratory tract infections [Citation23]), the cure rate [Citation32, Citation39, Citation40], or the time between consecutive events of interest [Citation26] were chosen as health outcomes. Except for stratification by age group (e.g. children, adolescents, and adults, where applicable), only a minority of studies reported results that were adjusted for participants’ characteristics.

In terms of economic outcomes, all studies reported medication costs, with four studies presenting costs of medication only [Citation26, Citation30, Citation32, Citation36]. Two studies reported that patients spent less money on conventional medication during homeopathic treatment but did not specify homeopathic treatment costs [Citation32, Citation36]. Consultation fees were included in 16 studies [Citation20, Citation22–25, Citation27, Citation28, Citation31,Citation33–35, Citation37–41] and hospital costs (if applicable for the study indication) as well as other direct health-care costs in seven studies [Citation20, Citation22, Citation25, Citation27, Citation28, Citation31, Citation33] while four studies considered also direct non-healthcare costs, e.g. transportation to consultations [Citation20, Citation22, Citation28, Citation40]. Indirect costs such as those attributable to sick leave were included in 11 studies [Citation20, Citation22, Citation25, Citation28, Citation29, Citation31, Citation33–35, Citation40, Citation41]; however, some of these studies reported only on changes in work absenteeism but presented no data on the financial implications [Citation34, Citation35, Citation41].

Two studies were model-based economic evaluations (i.e. 4-state Markov model [Citation20] or decision tree [Citation40]). In one study a retrospective insurer dataset-based economic evaluation was performed [Citation27], and one study retrospectively analyzed health records [Citation41]. The remaining publications were clinical study-based economic evaluations of which 13 were based on data from observational studies [Citation22, Citation23, Citation25, Citation26, Citation30–37, Citation39], two on data from open-label randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [Citation28,Citation38], one on data from a double-blind RCT [Citation29] and one was a case series [Citation24].

Two publications [Citation22, Citation29] were cost-utility analyses; all others reported on cost-effectiveness analyses. Six studies used a societal perspective [Citation20, Citation25, Citation28, Citation29, Citation31, Citation40], and five used a health-care payer perspective [Citation23, Citation27, Citation33, Citation38, Citation41], while the remaining publications used either multiple perspectives [Citation22,Citation34,Citation35] or did not report the perspectives used [Citation24, Citation26, Citation30, Citation32, Citation36, Citation37, Citation39].

Nine studies were monocentric [Citation23, Citation24, Citation28, Citation30, Citation32, Citation36, Citation38, Citation39, Citation41], 11 were multicentric [Citation20, Citation22, Citation25–27, Citation29, Citation31, Citation33–35, Citation37], and one publication did not mention the number of sites [Citation40]. Sample sizes varied considerably, ranging from fewer than 20 to several thousand patients per treatment group.

Four studies [Citation20, Citation23, Citation29, Citation40] assessed homeopathic combination products, and one study assessed one particular single remedy [Citation41], while all others investigated individualized homeopathic treatment. In four studies, homeopathic medicines were given in addition to standard care [Citation20, Citation23, Citation28, Citation30]. Most publications compared homeopathic treatment to standard care or, in case of add-on homeopathy, to standard care alone (14 of 21 papers [Citation20, Citation22, Citation23, Citation25–28, Citation30, Citation31, Citation33–35, Citation38, Citation40]). Two studies were based on pre- vs. post-treatment comparisons in a single group of patients [Citation32, Citation36], four used different comparator groups for health outcomes (pre- vs. post-treatment or published data) and costs (published data) [Citation24, Citation37, Citation39, Citation41], and one [Citation29] was placebo-controlled.

Indications for homeopathic treatment included respiratory tract and ear disorders (eight studies [Citation20, Citation23, Citation26, Citation28, Citation29, Citation34, Citation35, Citation39]), atopic eczema (two studies [Citation25, Citation31]), chronic arthritis [Citation40], dyspepsia [Citation38], diabetic polyneuropathy [Citation30], and dental surgery [Citation41]. The remaining seven studies investigated patients with various complaints or multimorbid patients [Citation22, Citation24, Citation27, Citation32, Citation33, Citation36, Citation37]. Four studies assessed only adults [Citation24, Citation29, Citation30, Citation38], six only children and/or adolescents [Citation25, Citation28, Citation31, Citation34, Citation35, Citation39], while the remaining studies assessed children, adolescents and adults or did not indicate the age range of their patient population [Citation20, Citation22, Citation23, Citation26, Citation27, Citation32, Citation33, Citation36, Citation37, Citation40, Citation41].

Due to their heterogeneity, a statistical analysis of clinical outcomes and health economic parameters across all studies was not possible.

3.1.2. Summary of main results

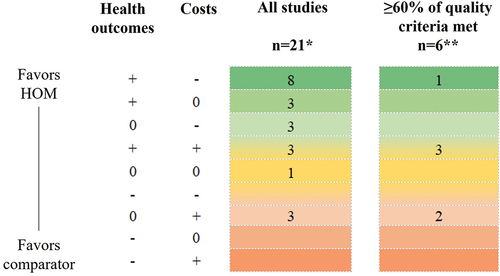

provides a summary of the main clinical and economic results of the studies, including an assessment as to whether the effect of homeopathic treatment in comparison to the control intervention was associated with a better (+), similar (0), or poorer (-) health outcome, as well as with decreased (-), similar (0), or increased (+) costs.

shows that among the 21 identified studies, 14 studies (66.7%) reported more favorable clinical outcomes in the homeopathy group than in the control group; seven (33.3%) observed similar treatment effects. Regarding economic outcomes, 11 studies (52.4%) found that the costs for sole or adjuvant homeopathic treatment were lower than for the comparator. Four studies (19.0%) reported similar costs for both treatments; six (28.6%) described increased costs with homeopathy.

Figure 2. Summary of economic evaluation of homeopathic treatment vs. comparator.

In a synthesis of the results for both health outcomes and costs, 11 studies (52.4%) found more favorable clinical effects for homeopathic treatment at costs which were lower [Citation23,Citation24,Citation29,Citation32,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation41] or similar [Citation30,Citation33,Citation34], and three studies (14.3%) reported similar health outcome results at lower treatment costs [Citation27,Citation38,Citation40]. Consequently homeopathic treatment was at least equally effective for less or similar costs than control treatment in a total of 14 out of 21 studies (66.7%). One study found similar health outcomes and similar costs for both treatment groups [Citation26]. Three other studies [Citation20,Citation22,Citation35] found improved clinical outcomes for homeopathic treatment at higher costs. The three remaining studies [Citation25,Citation28,Citation31] (14.3%) observed similar outcomes but at higher costs for homeopathic treatment and thus favored the comparator.

3.2. Result of quality assessment of included studies

Details of the quality assessment for each study using the CHEC list for health economic studies can be found in . Out of a total of 19 criteria, between two and 16 were met by the studies included in the review. When placed into proportion to the total number of criteria which applied (i.e. all criteria excluding those which were answered with n/a), this corresponds to 11% and 89%. Six studies (28.6% of 21) met more than 60% of the quality criteria [Citation20, Citation22, Citation25, Citation29, Citation31, Citation35], six (28.6%) met between 50 and 60% [Citation23, Citation28, Citation33, Citation34, Citation38, Citation40], and the remaining nine studies (42.9%) met less than 30% of the criteria [Citation24, Citation26, Citation27, Citation30, Citation32, Citation36, Citation37, Citation39, Citation41]. Studies with a CHEC quality assessment of at least 60% are also presented on .

Table 3. Quality assessment of included studies by means of the CHEC list.

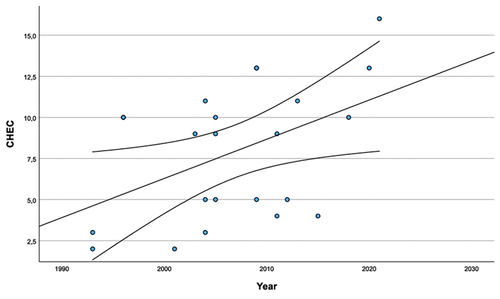

The average number and proportion of quality criteria met was 6.7 ± 3.4 (or 39.0% ± 20.6% of the applicable criteria; mean ± SD) for the ten studies published before 2009, 9.4 ± 4.3 (52.9% ± 23.8%) for the 11 studies published in or after 2009, and 8.1 ± 4.0 (46.3% ± 22.9%) for all studies. The linear regression analysis found a significant association between publication year (predictor) and CHEC quality score (dependent variable; β = 0.46, p = 0.026, R2 = 0.214) and thus confirmed an increase in the quality of the studies ().

Figure 3. Association between publication year (predictor) and CHEC quality score – linear regression analysis results (regression line and 95% confidence interval; data points are studies included in the analysis).

During their review of the study publications, the authors found various methodological shortcomings. Several studies had no ‘real’ comparator group and used simple pre-/post-treatment comparisons to assess health outcomes [Citation24, Citation32, Citation36, Citation37, Citation41]. Four studies had different comparators for costs and health outcomes [Citation24, Citation37, Citation39, Citation41], whereas one study described the type of intervention based only on the specialty of the patients’ GP [Citation27]. Some studies analyzed costs and outcomes over different time horizons [Citation25, Citation36–38], while in one study the time horizon was even not reported [Citation41]. Sensitivity analyses were either not done at all [Citation23, Citation24, Citation26,Citation27, Citation28, Citation30, Citation34–39, Citation41], or not properly done for both costs and outcome (e.g. [Citation32,Citation33]). Furthermore, data presented in tables and/or figures were not consistent with the accompanying text [Citation32, Citation38] or results were contradictorily described [Citation26]. Finally, various studies considered only medication costs for cost assessment [Citation26, Citation30, Citation32, Citation36] which is far from exhaustive.

4. Discussion

The first systematic review on economic evaluations of homeopathic treatments by Viksveen et al was published online in 2013 [Citation17]. To the best of our knowledge, no other comprehensive reviews have since been published in this area. Now, approximately ten years later, the aim was to provide an updated systematic review by including six new studies. In addition, we created a synthesis and summary of the complete clinical and economic data in a hierarchical decision matrix () [Citation21]. Lastly, we added a quality assessment of all studies using a standardized health economic tool based on expert consensus criteria [Citation18].

Beyond the six newly included studies, we also found other publications which offered information about costs and/or clinical outcomes but which did not meet our selection criteria. This included for example a publication describing six case reports which had no comparator group for the assessment of health outcomes and had therefore to be excluded [Citation42]. Another study had to be excluded because it examined only the costs for one comparator group [Citation43] whereas another study was not included because it only assessed costs for both the intervention and comparator groups [Citation44].

In the 21 reviewed studies, we found a great diversity of therapeutic indications, treatments, methodological approaches, and reported outcomes, which meant that an overall summary and evaluation was not obvious. It appears, however, that most of the studies indicated either an improvement of health outcomes under homeopathic treatment, a reduction of costs, or both and thus favored homeopathic treatment over control treatment. Lower proportions of investigations clearly favoring homeopathic treatment were found among studies meeting at least 60% of the applicable CHEC quality criteria, even though four out of the six studies with a CHEC score above 60% ascertained a positive effect of homeopathic treatment (adjuvant or alone) on clinical outcomes [Citation20,Citation22,Citation29,Citation35]. Of these one also showed lower costs for homeopathy [Citation29] and two showed homeopathic treatment to be cost-effective by incremental analysis [Citation20,Citation22].

Health economic studies are important for all therapeutic fields including CIM [Citation15,Citation16], and high quality is a prerequisite for using these data meaningfully [Citation17]. For the scope of this review, all 21 studies identified were assessed as economic evaluations, since they measured both costs and outcomes for two or more interventions (study selection criterion). With the CHEC list, a face-valid health economic tool [Citation18] was applied to assess their methodological quality. The quality of some identified studies was very low, which was reflected by their low score on the CHEC list (<30% for two-fifths of them [Citation24,Citation26,Citation27,Citation30,Citation32,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation41] compared to an average of 46.3% for all studies), and various methodological deficits were found. Encouragingly, however, a clear trend toward higher quality standards in more recently published research was seen. Indeed, a look at the two most recent publications showed that they belonged to those with the highest quality ratings according to CHEC (89% and 72%). One re-analyzed the data of a randomized, controlled trial [Citation20] while the other used the data of a large cohort study [Citation22]. In addition to being multicenter studies, they both performed a comprehensive analysis of costs, taking into account direct health-care costs (costs of medication, consultation fees, hospital and other care), direct non-medical costs (e.g. for transportation), as well as indirect costs such as sick-leave payment and reduced productivity. Also, in both studies, the research question was clearly stated, the economic study design well-chosen, important outcomes identified and measured appropriately, the time horizon suitably chosen, and incremental analyses as well as sensitivity analyses performed. One study [Citation22] even considered quality-of-life measures as outcomes for calculating quality-adjusted life years associated with homeopathic treatment.

The positive trend in health outcomes and costs found in our results are consistent with those of a review on economic evaluations reporting cost-effectiveness of CIM therapies, particularly in higher-quality studies. Even if CIM included homeopathic treatment, the authors of this review did not report outcome data separately for homeopathy [Citation45]. The methodological issues described in our review are almost identical to quality issues recently identified in studies of other therapy concepts such as acupuncture [Citation46] or Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) [Citation47]. Also, in these fields there is an important need for high-quality economic research to meet the needs of health decision makers [Citation46,Citation48].

The limitations of the present investigation lie within the nature of systematic reviews: the search procedure was broad and delivered a high number of hits. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that the search terms ‘cost’ and ‘homeopathy’ may have missed studies if the key words were not indexed accordingly. For example, the study by Colombo et al [Citation23] could only be found by manual search, since ‘homeopathy’ does not appear as an indexed term. Moreover, relevant cost-effectiveness data may not be publicly accessible (e.g. register data: information in trial registers of planned or ongoing studies with cost-effectiveness as an endpoint) or only available as congress abstract (e.g [Citation49,Citation50]). Also, it cannot be ruled out that economic evaluations which report that homeopathy is not cost-effective are less likely to be published. This problem, also known as publication bias, affects all areas of medical research and is one of the elements which can distort evidence by overestimating the benefits of a treatment [Citation51]. Finally, the external validity of our conclusions is limited by methodological deficits of the publications included.

5. Conclusion

In addition to the systematic review of Viksveen et al [Citation17], our systematic review identified six further studies that contribute to the overall evidence on cost-effectiveness of homeopathy. In 14 out of 21 studies, homeopathic treatment favored control treatment in a synthesis of costs and effectiveness. For two studies showing better health outcomes but at higher costs, additional incremental analysis indicated cost-effectiveness of homeopathic treatment. Studies were, however, highly heterogeneous in term of the conditions investigated, the treatments administered, the design of the investigations, and the clinical and economic outcomes assessed.

Although most recent studies yield promising data about the benefit of homeopathy for the public health system, the conclusion drawn by Viksveen et al ten years ago is still applicable today: based on the existing evidence, no firm conclusion about the cost-effectiveness of homeopathy can be drawn. Further high-quality cost-effectiveness studies are needed so that more robust statements may be made.

6. Expert opinion

Ten years after the work of Viksveen et al [Citation17], the favorable cost-effectiveness assessment of homeopathic treatments from a small number of existing high-quality studies continues to be undercut by too many examples of methodologically limited research. Thus, the lessons to be learned from the data and the recommendations for further research into the cost-effectiveness of homeopathic treatments remain essentially the same: the use of properly planned randomized controlled trials would greatly improve the internal validity of the data. Moreover, studies should focus on a well-defined condition (or should be sufficiently large to allow separate assessments for multiple conditions), and study results should yield claims with direct relevance to the respective cohort. This in turn should be ensured by appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria. For generalizability, single-center studies should be avoided. As far as costs are concerned, studies should investigate all relevant expenses (direct and indirect) and should not be limited to medication costs, in part because particularly in homeopathy, consultation costs may be many times higher than the expenses for medicines. Finally, outcomes should be selected to (a) enable researchers to reliably distinguish treatment success from failure, and to (b) provide a standardized assessment of cost-effectiveness, e.g. based on QALYs.

In 2011, Ostermann et al [Citation52] concluded that more high-quality studies are needed for CIM for a valid overall assessment of cost-effectiveness. Here it is important that health economic aspects are considered in an early planning stage of studies, which would facilitate economic assessments alongside clinical trials as is the case in trial-based economic evaluations. Gold standard trial-based economic evaluations should have an adequate power (among other things, so they can detect differences in costs), a judicious time horizon and sensibly chosen outcomes. Health economic modeling is another powerful tool which can aid decision makers to identify the cost-effectiveness of CIM interventions using different scenarios [Citation53]. Only when research is performed under these conditions can meaningful conclusions about the cost-effectiveness of homeopathic treatments be made.

Over the next five years, we expect to see a further quality improvement in economic evaluations of homeopathic treatments, in line with what we have already witnessed in the most recent studies. This is a necessary prerequisite to persuade policy and decision makers to consider data and results about the cost-effectiveness of homeopathic treatments when they make pricing and/or reimbursement decisions. Furthermore, such research plays an important role in convincing physicians and patients about the added value of homeopathic treatments.

Article highlights

Evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of homeopathic treatments are needed as a basis for rational healthcare decision-making.

A total of 21 studies published between 1993 and 2021 were reviewed which assessed the costs and health outcomes of homeopathic therapy for indications such as respiratory tract and ear disorders, atopic dermatitis, chronic arthritis, dyspepsia, and diabetic polyneuropathy.

Compared to control treatment, most of the studies indicate either an improvement of health outcomes under homeopathic treatment, a reduction of costs, or both, and they thus favor homeopathic treatment.

The favorable cost-effectiveness assessment of homeopathic treatments results from a few high-quality studies. Due to this low number, no firm conclusion about the cost-effectiveness of homeopathy can be drawn.

A quality assessment based on the CHEC list shows a trend toward higher-quality research over time. Nevertheless, the methodological quality of more than two-thirds of the studies reviewed was moderate or poor, and more high-quality health economic studies are needed. Shortcomings included poor description of study populations and competing alternatives, failure to capture and evaluate all relevant costs, and failure to perform incremental and sensitivity analysis.

Declaration of interest

J Burkart and S De Jaegere are employees of Deutsche Homöopathie-Union DHU-Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG Karlsruhe, Germany. The other authors received honoraria of Deutsche Homöopathie-Union DHU-Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG Karlsruhe, Germany.

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Author contributions

All authors equally contributed to the conceptualization of the review. Literature review was performed by J Burkart and C Raak. Data extraction and quality assessment was performed by J Burkart and C Raak. Here C Raak was supported by T Ostermann and J Burkart was supported by S De Jaegere. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by S Simoens. All authors read, revised, and edited the drafted manuscript and approved the final version.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andreas Völp of Psy Consult Scientific Services for providing statistical support and medical writing services and the Information Services & Library team of Deutsche Homöopathie-Union DHU-Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG Karlsruhe, Germany for conducting the literature search.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Relton C, Cooper K, Viksveen P, et al. Prevalence of homeopathy use by the general population worldwide: a systematic review. Homeopathy. 2017;106(2):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2017.03.002

- Anheyer D, Koch AK, Anheyer M, et al. Integrative pediatrics survey: parents report high demand and willingness to self-pay for complementary and integrative medicine in German hospitals. Complement Ther Med. 2021;60:102757. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2021.102757

- Adam D, Keller T, Mühlbacher A, et al. The value of treatment processes in Germany: a discrete choice experiment on patient preferences in complementary and conventional medicine. Patient. 2019;12(3):349–360. doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0353-1

- Colas A, Danno K, Tabar C, et al. Economic impact of homeopathic practice in general medicine in France. Health Econ Rev. 2015;5(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13561-015-0055-5

- Studer HP, Busato A. Comparison of Swiss basic health insurance costs of complementary and conventional medicine. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18(6):315–320. doi: 10.1159/000334797

- Jain A. Does homeopathy reduce the cost of conventional drug prescribing? A study of comparative prescribing costs in general practice. Homeopathy. 2003;92(2):71–76. doi: 10.1016/s1475-4916-03-00004-3

- May U, Bauer C. Apothekengestützte Selbstbehandlung bei leichteren Gesundheitsstörungen – Nutzen und Potenziale aus gesundheitsökonomischer Sicht. Gesundheitsökonomie & Qualitätsmanagement. 2017;22(S 01):S12–S22. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-120487

- Securvita Krankenkasse. Securvita-Studie zur Homöopathie: Wirtschaftlich und wirksam. Securvital Das Magazin für Alternativen im Versicherungs- und Gesundheitswesen. 2021;20(4):6–11.

- Ostermann JK, Reinhold T, Witt CM, et al. Can additional homeopathic treatment save costs? A Retrospective cost-analysis based on 44500 insured persons. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134657

- Ostermann JK, Witt CM, Reinhold T, et al. A retrospective cost-analysis of additional homeopathic treatment in Germany: long-term economic outcomes. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0182897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182897

- Baars EW, Zoen EB, Breitkreuz T, et al. The contribution of complementary and alternative medicine to reduce antibiotic use: a narrative review of health concepts, prevention, and treatment strategies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:5365608. doi: 10.1155/2019/5365608

- Grimaldi-Bensouda L, Bégaud B, Rossignol M, et al. Management of upper respiratory tract infections by different medical practices, including homeopathy, and consumption of antibiotics in primary care: the EPI3 cohort study in France 2007-2008. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e89990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089990

- Grimaldi-Bensouda L, Abenhaim L, Massol J, et al. Homeopathic medical practice for anxiety and depression in primary care: the EPI3 cohort study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:125. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1104-2

- Palm J, Kishchuk VV, Ulied À, et al. Effectiveness of an add-on treatment with the homeopathic medication SilAtro-5-90 in recurrent tonsillitis: an international, pragmatic, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2017;28:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.05.005

- Witt CM. Health economic studies on complementary and integrative medicine. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18(1):6–9. doi: 10.1159/000324615

- Ostermann T. On moving house, dachshunds, preferences, dictators, and health economics. J Complement Integr Med. 2022;28(12):909–910. DOI:10.1089/jicm.2022.29112.editorial.

- Viksveen P, Dymitr Z, Simoens S. Economic evaluations of homeopathy: a review. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(2):157–174. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0462-7

- Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, et al. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on health economic criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(2):240–245. doi: 10.1017/S0266462305050324

- Simoens S. Health economic assessment: a methodological primer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(12):2950–2966. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6122950

- Ostermann T, Park AL, De Jaegere S, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis for SilAtro-5-90 adjuvant treatment in the management of recurrent tonsillitis, compared with usual care only. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2021;19(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12962-021-00313-4.

- Nixon J, Khan KS, Kleijnen J. Summarising economic evaluations in systematic reviews: a new approach. BMJ. 2001;322(7302):1596–1598. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7302.1596.

- Kass B, Icke K, Witt CM, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatment with additional enrollment to a homeopathic integrated care contract in Germany. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):872. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05706-4.

- Colombo GL, Di Matteo S, Martinotti C, et al. The preventive effect on respiratory tract infections of Oscillococcinum®. A cost-effectiveness analysis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:75–82. doi: 10.2147/ceor.S144300

- Frei H. Homeopathic treatment of multimorbid patients: a prospective outcome study with polarity analysis. Homeopathy. 2015;104(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2014.09.001

- Roll S, Reinhold T, Pach D, et al. Comparative effectiveness of homoeopathic vs. conventional therapy in usual care of atopic eczema in children: long-term medical and economic outcomes. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054973.

- Basili A, Lagona F, Roberti di Sarsina P, et al. Allopathic versus homeopathic strategies and the recurrence of prescriptions: results from a pharmacoeconomic study in Italy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:969343. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep023

- Kooreman P, Baars EW. Patients whose GP knows complementary medicine tend to have lower costs and live longer. Eur J Health Econ. 2012;13(6):769–776. doi: 10.1007/s10198-011-0330-2

- Thompson EA, Shaw A, Nichol J, et al. The feasibility of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial to compare usual care with usual care plus individualised homeopathy, in children requiring secondary care for asthma. Homeopathy. 2011;100(3):122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2011.05.001

- Kneis KC, Gandjour A. Economic evaluation of Sinfrontal in the treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis in adults. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2009;7(3):181–191. doi: 10.1007/BF03256151

- Pomposelli R, Piasere V, Andreoni C, et al. Observational study of homeopathic and conventional therapies in patients with diabetic polyneuropathy. Homeopathy. 2009;98(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2008.11.006

- Witt CM, Brinkhaus B, Pach D, et al. Homoeopathic versus conventional therapy for atopic eczema in children: medical and economic results. Dermatology. 2009;219(4):329–340. doi: 10.1159/000248854.

- Sevar R. Audit of outcome in 455 consecutive patients treated with homeopathic medicines. Homeopathy. 2005;94(4):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2005.07.002

- Witt C, Keil T, Selim D, et al. Outcome and costs of homoeopathic and conventional treatment strategies: a comparative cohort study in patients with chronic disorders. Complement Ther Med. 2005;13(2):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.03.005

- Trichard M, Chaufferin G, Nicoloyannis N. Pharmacoeconomic comparison between homeopathic and antibiotic treatment strategies in recurrent acute rhinopharyngitis in children. Homeopathy. 2005;94(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2004.11.021

- Trichard M, Chaufferin G, Dubreuil C, et al. Effectiveness, quality of life, and cost of caring for children in France with recurrent acute rhinopharyngitis managed by homeopathic or non-homeopathic general practitioners. Dis Manage Health Outcomes. 2004;12(6):419–427. doi: 10.2165/00115677-200412060-00009

- Slade K, Chohan BP, Barker PJ. Evaluation of a GP practice based homeopathy service. Homeopathy. 2004;93(2):67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2004.02.005

- Van Wassenhoven M, Ives G. An observational study of patients receiving homeopathic treatment. Homeopathy. 2004;93(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2003.11.010

- Paterson C, Ewings P, Brazier JE, et al. Treating dyspepsia with acupuncture and homeopathy: reflections on a pilot study by researchers, practitioners and participants. Complement Ther Med. 2003;11(2):78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0965-2299(03)00056-6

- Frei H, Thurneysen A. Homeopathy in acute otitis media in children: treatment effect or spontaneous resolution? Br Homeopath J. 2001;90(4):180–182. doi: 10.1054/homp.1999.0505

- Bachinger A, Rappenhöner B, Rychlik R. Zur sozioökonomischen Effizenz einer Zeel-comp.-Therapie im Vergleich zu Hyaluronsaeure bei Patienten mit Gonathrose. [Socioeconomical efficiency of a Zeel-comp.-therapy in comparison to hyaluronic acid in patients with gonarthrosis]. Z Orthop. 1996;134(4):Oa20–1.

- Feldhaus HW. Cost-effectiveness of homoeopathic treatment in a dental practice. Br Homeopath J. 1993;82:22–28. doi: 10.1016/S0007-0785(05)80950-0

- Libessart Y. Une alternative homéopathique en pédiatrie, le purpura rhumatoïde de Schönlein-Henoch. La Revue d’Homéopathie. 2012;3(4):140–142. doi: 10.1016/j.revhom.2012.10.013

- Fibert P, Peasgood T, Relton C. Rethinking ADHD intervention trials: feasibility testing of two treatments and a methodology. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178(7):983–993. doi: 10.1007/s00431-019-03374-z

- Singh P, Mukherjee K. Cost-benefit analysis and assessment of quality of care in patients with hemophilia undergoing treatment at national rural health mission in Maharashtra, India. Value Health Reg Issues. 2017;12:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2016.11.003

- Herman PM, Poindexter BL, Witt CM, et al. Are complementary therapies and integrative care cost-effective? A systematic review of economic evaluations. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001046

- Li H, Jin X, Herman PM, et al. Using economic evaluations to support acupuncture reimbursement decisions: current evidence and gaps. BMJ. 2022;376:e067477. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067477

- Xiong X, Jiang X, Lv G, et al. Evidence of Chinese herbal medicine use from an economic perspective: a systematic review of pharmacoeconomics studies over two decades. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:765226. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.765226

- Yan J, Bao S, Liu L, et al. Reporting quality of economic evaluations of the negotiated traditional Chinese medicines in national reimbursement drug list of China: a systematic review. Integr Med Res. 2023;12(1):100915. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2022.100915

- von Ammon K, Sauter U, Frei H, et al. Classical homeopathy helps hyperactive children –a 10-year follow-up of homeopathic and integrated medical treatment in children suffering from attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity. Eur J Integr Med. 2012;4:73–74. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2012.07.645

- Thompson E, Griffin T, Hamilton W, et al. Economic evaluation of the Bristol homeopathic hospital: final results of the BISCUIT feasibility study. Homeopathy. 2014;103(1). doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2013.10.037

- Bradley SH, DeVito NJ, Lloyd KE, et al. Reducing bias and improving transparency in medical research: a critical overview of the problems, progress and suggested next steps. J R Soc Med. 2020;113(11):433–443. doi: 10.1177/0141076820956799

- Ostermann T, Krummenauer F, Heusser P, et al. Health economic evaluation in complementary medicine: development within the last decades concerning local origin and quality. Complement Ther Med. 2011;19(6):289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.09.002

- Ostermann T, Baars E, McDaid D. Time to stand up and be counted: the need for an economic case for investment. Complement Ther Med. 2016;27:137–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.06.008